William Ah Sang and the Chinese Question of 1869

Processing Request

Processing Request

In the wake of the American Civil War, planters across the South considered the pros and cons of recruiting Chinese laborers to sustain the region’s agricultural traditions. An interstate summit on the topic, held in Memphis in 1869, stoked racial fears and produced mixed results. While some communities moved forward with plans to hire thousands of “Celestials,” South Carolina planters soon rejected the premise. Four years later, William Ah Sang, a connoisseur of Asian tea, became Charleston’s first resident of Chinese ancestry, opening the door for generations of urban immigrants.

The story of William Ah Sang’s brief career in South Carolina is a rather compact tale when stripped of its historical context. To understand why Charleston was devoid of Chinese-American residents prior to 1873, we have to consider the bigger picture of regional, national, and international politics of his day. Charleston was a turbulent community in the years following the end of the American Civil War in 1865, deeply divided by resentment and prejudice. Immigrants from China were then streaming into California and the Western territories, but the American South was largely too preoccupied with its own internal problems to take notice. Following a series of events that matured in 1869, however, the people of South Carolina and their neighbors paused to consider what became known as “the Chinese question.”

During several decades around the middle of the nineteenth century, the people of China endured years of famine, natural disasters, political repression, and several concurrent and bloody rebellions. The relentless strife and danger induced many to leave the vast country and seek their fortunes elsewhere. Chinese laborers began arriving in California in 1849 during the Gold Rush and their numbers accelerated during the American Civil War. Most worked on the railroads that were slowly linking the new Western territories along the Pacific coast of North America. By the end of the 1860s, there were tens of thousands of Chinese men in the American West, but only a handful east of the Rocky Mountains.

Americans of that era generally referred to Chinese nationals disparagingly as “Chinamen” or “coolies,” a pejorative term originally applied to East Indian migrant workers in British colonies, but in the U.S. applied to contract laborers imported from China. The American press of the mid-nineteenth century was also fond of describing Chinese people generically as “celestials,” a term derived from the anglicized version of a poetic name for China, “the Celestial Empire.” Restrictive policies enacted by the federal government during this era abridged the civil rights of the migrant workers, who generally returned to China after a period of servitude and were not eligible to become naturalized citizens of the United States. The concept of identifying them as “Asian Americans” was practically unthinkable at the time.

Most of the Chinese immigrants in California and adjacent territories during the 1860s labored on various railroad projects that culminated in the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in the United States in May 1869. That project created a continuous ribbon of steel rails between San Francisco and Council Bluffs, Iowa, and from thence to numerous destinations across the eastern half of North America. A few months later, freight and passengers began moving overland from coast to coast for the first time.

The construction of the transcontinental railroad demonstrated the viability of importing large numbers of Chinese laborers who were eager to escape the strife of their native land. Like the indentured servants of the earlier British colonies, the Chinese laborers or “coolies” worked on multi-year contracts and endured harsh conditions rewarded by low wages. The completion of the transcontinental railroad also opened the door to the possibility of transporting similarly large numbers of Chinese laborers to work in the fields of Southern plantations formerly cultivated by enslaved people of African descent. At this point, planters across the Southern states began to take a greater interest in the labor conditions of distant California.

In 1869, formerly-enslaved African-Americans formed the majority of the population in the state of South Carolina, in Charleston County, and in the City of Charleston.[1] Many of those people rejected the notion of continuing a career of plantation labor, however, choosing instead to settle in various urban centers or to move northward in search of factory jobs. Their post-war withdrawal from plantation agriculture caused widespread panic among landowners accustomed a steady supply of cheap labor. South Carolina’s economy was largely dependent on the export of rice and cotton, but who would tend the fields and harvest the crops?

In the summer of 1869, newspapers across the United States carried articles predicting the imminent arrival of many thousands of Chinese laborers to be distributed from the West to the East.[2] Resourceful planters from various Southern states gathered in Memphis, Tennessee, in July 1869 “to consider the question of inviting and encouraging Chinese immigration to the South.”[3] The main result of the convention was a recommendation to organize a joint-stock corporation with at least one million dollars of capital, or perhaps one such corporation in each of the Southern states, to recruit, transport, and distribute thousands of contract laborers directly from China.[4]

A few days after the Memphis convention, the South Carolina Agricultural and Mechanical Society gathered to debate “the question of Chinese labor [that] has been occupying the attention of Southern planters.” A committee appointed “to collect all the necessary information and cost of introducing that description of labor into South Carolina” reported their findings to an eager audience that July. The copious volume of data available from California portrayed the Chinese immigrants as industrious, skillful, and docile. On the other hand, “they retained their peculiar habits and distinctive elements as at home, and had their temples to Confucius,” and were described as “inflexible in their attachment to their heathenism, and with little or no moral conceptions.” In South Carolina and across the South, however, “there are neglected plantations, and thousands upon thousands of idle and unproductive acres, for the culture of which the white and colored labor of the South is not sufficient.” Many of the formerly enslaved agricultural workers had forsaken plantation labor. What Southern planters desired, said the committee report, “is immigration, but an immigration which will not denigrate our civilization and prove an element of vice and destruction.” They concluded their report not with a solution, but a pair of lingering questions: “Can this [Chinese] labor be provided at such prices as to be really accessible generally to the people of the state? And when thus provided can it be adapted to our system of agriculture, and made actually useful for the development and civilization of the state?”[5]

Debate of the Chinese question continued through the remainder of 1869, but the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in the spring of 1870 transformed the conversation. The amendment, which cemented several post-war Reconstruction Acts promulgated by Congress, prohibited the federal and state governments from denying or abridging a citizen’s right to vote on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Masses of Chinese immigrants, in theory, would be eligible for future citizenship and might even be elected to positions of power in any one of the United States. The hypothetical extension of civil rights to Asian Americans quickly dampened the initial enthusiasm for Chinese immigration across the American South.

In early May 1870, the South Carolina Institute hosted a three-day “Agricultural and Immigration Convention” in Charleston. Chairman William M. Lawton, president of the Institute, explained the purpose of the gathering. The large African-American population of South Carolina had been declining steadily since the end of the Civil War and the death of slavery, which empowered formerly-enslaved people to move northward and westward in their constitutional pursuit of happiness. At the current rate of outward migration, said Lawton, “in less than 44 years the entire colored population of South Carolina will have disappeared.”[6] Those interested in perpetuating the state’s agricultural traditions needed to devise some means to induce immigrants to settle in South Carolina.

Most of the convention’s debate focused on the recruitment of European emigrants who would settle permanently in South Carolina and become naturalized citizens of the United States. Only in the final hours of the three-day event did someone propose to import masses of Chinese laborers. One advocate of the plan noted that in California “the Chinese laborer has shown himself [to be] industrious, frugal, obedient and attentive to the interests of his employer. . . . His shrewdness and wonderful imitative powers enable him readily to acquire the necessary information and to perform with facility every kind of farm labor.” An opponent countered by observing that California and South Carolina were very different places in 1870. The existence of a Black majority population in the Palmetto State, combined with the advent of federal civil rights legislation, was a source of great anxiety for the White minority accustomed to controlling local and state government in South Carolina. “The gravest of all considerations,” he said, “was the danger, politically, that would result from an infusion of Chinese, who might, in the course of time, increase the difficulties which already exist to a lamentable degree.” In the end, most of the conventioneers agreed they did not yet possess a sufficient knowledge of the Chinese question to form an opinion.[7]

Immediately after the conclusion of the three-day immigration convention, John McCrady of Charleston considered the matter more carefully and published a long essay against the proposed recruitment of foreigners. Although he readily acknowledged “that Chinese labor, and a great deal of it, is the readiest, the cheapest, and the very best solution of our difficulties,” McCrady was adamantly opposed to the prospect of large-scale Asian immigration at that moment. The problem, he said, involved “the whole social structure” of Southern civilization, characterized by “the co-existence of two or more races indelibly distinguished by nature and differing in the capacities for intellectual and political development.” “The Chinese,” said McCrady to an audience of White readers, “we know to be our inferiors,” and “the introduction of another inferior race among us will increase our political troubles.” Because the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution and the Reconstruction Acts of the U.S. Congress guaranteed to all adult male citizens the right to vote and hold elected office, the influx of immigrants into South Carolina would determine the state’s political future. “The only possible policy we can pursue,” said McCrady, “is the policy of making this a white man’s country. We must make sure that the whites shall be a majority, because the majority will govern.” Religious concerns also colored McCrady’s conservative opinion. “To introduce the Chinese is to introduce heathenism into a Christian country.” “If to admit heathen, is to admit heathen legislators, then indeed we shall be voluntarily giving an advantage to heathenism.”

McCrady reduced the matter to “one paramount question” for the consideration of his White audience, “before we introduce the Chinaman or any other laborer of inferior race”: “Will he, after his arrival in our midst, be controlled and directed by the superior intellect of the white race?” If the Chinese laborer will acquiesce to White authority, said McCrady, then “the problem is perhaps already solved, and it only remains to bring on the laborers as fast as steam ships and rail roads can transport them. But if not, be assured that to introduce them will be first to abandon principle, and then to do all we can do towards wiping out our own existence as a people.”[8]

In July 1870, the U.S. Congress ratified a statute commonly known as the Naturalization Act of 1870. The law formally confirmed the right of naturalization to “aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent,” but it upheld the traditional exclusion of persons of Chinese ancestry from the same benefit. This exception placated those who feared the complete erosion of a White majority in the United States, but it did not cause South Carolina planters to reconsider the question of recruiting Chinese laborers. By the summer of 1870, the Chinse question of 1869 was a dead letter. The risk to the traditions of White supremacy were simply too great.[9]

For most residents of Charleston County in 1870, the only Chinese element of their daily lives was tea, which they drank hot or chilled by ice imported from New England.[10] Tea had been available in Charleston since the early eighteenth century, and could be purchased at small corner grocery stores like that run by Samuel H. Wilson. Born in Charleston to Irish parents in 1846, Wilson moved to New York as a teenager to live with relatives involved in the grocery business. He returned to Charleston after the Civil War and in 1868 opened a small store at the northwest corner of Society and Anson Streets.[11] Selling a variety of dry and packaged comestibles as well as coffee and tea, Wilson strove to distinguish his business from other grocery concerns in Charleston. In the spring of 1870, he coined a marketing slogan that he repeated constantly for many years: “Have you tried my dollar tea?”[12]

In the spring of 1871, Sam Wilson formed a partnership with his younger brother, James, and moved their business to the east side of King Street, midway between Society and Wentworth Streets, now known as No. 284 King Street.[13] Ensconced within the heart of Charleston’s busy retail district, the Wilson brothers competed with a number of similar establishments of varying sophistication. Their strategy was to aim for the higher end of the packaged food market, offering imported delicacies that appealed to discriminating palates. Coffee and tea continued to form a relatively small proportion of their sales until the summer of 1872. In May of that year, the United States government removed existing import tariffs on Asian tea, causing the price of the leafy stuff to plummet across the nation.[14] Retailers like the Wilson brothers were able to lower their prices, which attracted more customers and increased their profits. The Wilsons capitalized on the tariff change by ordering large quantities of bulk tea from their suppliers in New York. On the ninth of August, customers and newspaper reporters in Charleston noticed that “the sidewalks in front of Wilson’s grocery were piled high yesterday morning with freshly arrived tea boxes.”[15]

By the end of 1872, the Wilson Brothers had curated a business that the local press described as “a first-class grocery house” and a “model establishment.” Although their King Street store contained “everything usually to be found in all well-regulated grocery stores,” said the press, “teas are made a specialty by this house.”[16] Samuel Wilson celebrated his business success by purchasing lot and building a house at the northwest corner of Green and College Streets, a modified version of which now forms part of the campus of the College of Charleston (No. 11 College Way, called the Sottile House). In the summer of 1873, the Wilson brothers expanded their business again by embarking on a bold marketing campaign revolving around a unique Chinese asset.

On the 15th of July, 1873, the steamship James Adger docked in Charleston and began unloading cargo and passengers from New York.[17] Among the merchandize onboard were a number of wooden chests consigned to the grocery firm of S. H. Wilson and Brother, accompanied by an unfamiliar face. “A Live Chinaman” was now present in the city, announced the Charleston News and Courier the following day. He stepped ashore “clad in Celestial toggery [that is, loose-fitting, traditional Chinese attire], and attracted much attention wherever he went.” Word of his arrival on July 15th induced a journalist to track his movements and interview the curious visitor. “He speaks English with facility,” said the published report, “and is to become a permanent resident of Charleston, having been engaged by the pushing grocery house of Wilson & Bro[ther] . . . to preside over the large and constantly increasing tea and coffee department of their business. For this post he is especially adapted by long experience as a tea taster in Canton [now Guangzhou], his native city, and more recently in San Francisco.” The reporter noted that he had almond-shaped eyes and the “unmistakable pig-tail” worn by so many Chinese men of that era. “Ah Sang—for that is his name—is intelligent, educated and courteous.”[18]

His two-syllable name probably represented a family name, “Ah,” and a given name, “Sang,” in the traditional order of his native Chinese culture. The European name “William,” which he used inconsistently in Charleston, was apparently meant to facilitate his American career. He was born in 1848 or 1849 and, according to his obituary, came to the United States under the care of Anson Burlingame, minister to China appointed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1861. Ambassador Burlingame returned to America in the spring of 1868 and immediately brokered a treaty that strengthened trade relations between the two nations. Ah Sang likely traveled from Hong Kong to California as part of Burlingame’s entourage and settled briefly in San Francisco.

In late September 1872, however, William Ah Sang walked into a newspaper office in Savannah, Georgia, wearing his “native dress,” and introduced himself as a “tea merchant.” He was said to have impressed a reporter “as much by his novelty as by his dignified manner and fluent English.”[19] One of the Wilson brothers of Charleston likely traveled to Savannah to meet Ah Sang during the spring of 1873 and induced him to join their business in the Palmetto City. Because the grocers were accustomed to purchasing bulk tea through contacts in New York, they apparently sent him to the Big Apple to select teas for their shop in Charleston. Having accomplished his mission in early July, Ah Sang boarded a steamship on July 12th and headed southward.

On July 16th, 1873, the day after his arrival in Charleston, the Wilson brothers placed a notice in the local newspaper announcing their connection with the young Chinese national: “At great expense, they have secured the services of Mr. Ah Sang, who had, previous to receiving a call from us, held the lucrative position of Tea Taster and Selecter [sic] for one of the largest importing houses in San Francisco. The Messrs. Wilson take pride in being able to employ the services and judgment of Mr. Ah Sang for the benefit of the Charleston public, and trust that this will be appreciated by their customers.”[20]

In a new advertisement published on July 18th, the Wilson brothers announced with obvious pride that “our teas have all been selected during the last three weeks by Mr. Ah Sang, who, in future, will have sole control of our Tea Department, which is worthy [of] the attention of connoisseurs.”[21] Meanwhile, the Irish-American grocers were busy preparing the final piece of the new marketing campaign. Ah Sang and his choice teas were not simply exotic décor to embellish the Wilsons’ King Street shop. Rather, he was central to a rebranding of their business identity. In mid-August 1873, the grocery store known as “S. H. Wilson & Brother” officially changed its name to the “Charleston Teapot.”[22]

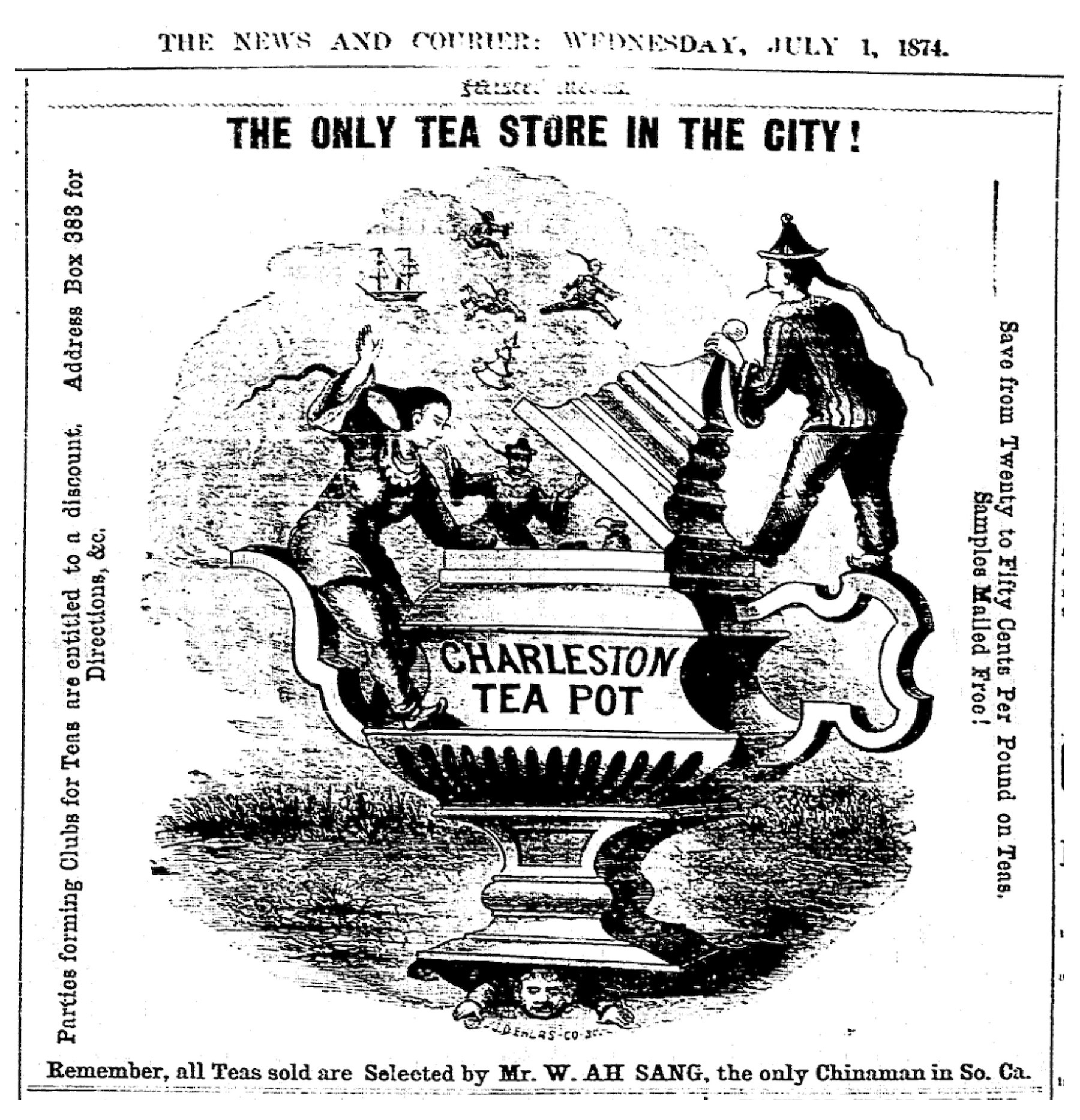

William Ah Sang might have been the first person of Chinese ancestry to settle in Charleston, but he was not the first of his kind in South Carolina.[23] As I described in Episode No. 232 and No. 233, Oqui Adair had settled in the Palmetto State in 1857 and had been employed as a gardener in Columbia since 1864. To differentiate the two men in the autumn of 1873, the Wilson brothers informed the public that they employed “the only educated Chinaman in South Carolina.”[24] Oqui apparently adopted American-style clothing and hairstyle shortly after his arrival in the United States, but it appears that William Ah Sang did not. Although it is possible that he continued to wear a long pigtail or queue and loose-fitting garments out of devotion to his Chinese ancestry, the traditional Asian aesthetic of that era might have been essential to his career in Charleston. Ah Sang was a novelty in the Palmetto City at that moment, and his employers might have encouraged him to maintain his distinctive appearance as means of promoting their business. Consider, for example, the illustrated advertisement for the Charleston Teapot first published in July 1874, which depicts two pig-tailed figures in the foreground, opening the lid of an enormous teapot, with several similar figures flying through the air in the background.[25] Pedestrians passing the Wilson brothers’ establishment in King Street would have seen Ah Sang through the shop’s window, and the firm directed the public to find the store at the “sign of the Live Chinaman.”[26] In the summer of 1874, however, the Wilson brothers suspended a large, sheet-metal teapot above the sidewalk of their King Street facade, belching steam generated by coffee-roasting machinery on the second floor above the shop.[27]

In the early months of 1874, the proprietors of the Charleston Teapot hired local artist Charles W. Stiles to decorate their tea department in a manner likely inspired by conversations with William Ah Sang. Mr. Stiles painted three large images for the north wall of the building’s interior, although it’s not clear if they were murals or framed canvases. A published review of the artwork provides a valuable description of the store’s interior: “The first picture, which is five by seven feet, represents the exterior of a Chinese palace. The second is a water landscape, seven by fourteen feet, representing a scene in the harbor of Hong Kong, and the third, which is of the same dimensions as the first, is a Chinese wedding scene. The whole is surmounted by an elaborate and grotesque scroll work.” Arranged on the floor below the pictures stood a display of twenty-eight stacked wooden tea chests, the fronts of which were painted “in keeping with the panorama above, and represent various features in the home life of the descendants of Confucius.” The focal point of the display was not the artwork or the tea chests, however, but the sales clerk from China. “The handsome and genial features of Mr. Ah Sang, the tea taster of the establishment, embellish the very pretty work of the ‘Melican’ artist, and a childlike smile lights up his features as he explains the views or weighs out a pound of dollar tea to the customers of the establishment.”[28]

The wedding scene painted by Mr. Stiles in 1874 might have been inspired by romantic notions of the Asian tea taster. One year later, on the 14th of August, 1875, William Ah Sang married Clara Davis, an attractive eighteen-year-old White native of Charleston. Although the ceremony was performed by the pastor of the Wentworth Street Lutheran Church, the ceremony and reception took place at a boarding house then known as No. 2 College Street (now under Physicians Memorial Auditorium at the College of Charleston). A newspaper notice described the reception as “quite a brilliant affair, being attended by a large number of the friends of the newly-wedded pair. Mr. Ah Sang was attired in the habit of his native country, which on this occasion was a richly trimmed satin blouse, with trowsers [sic] of a dark blue material, and shoes of China make and style. The bride was dressed in white satin, trimmed with lace, her head was adorned with a wreath of orange blossoms, and a handsome laced veil fell in graceful folds, enhancing the beauty of a pretty face. It is stated that this happy Benedict, having prospered with his present employers, has resolved to make Charleston his permanent home.”[29]

Nine months after the wedding, Clara Davis Ah Sang gave birth to twin girls, named Clara and Martha, in early May 1876. The joyous occasion was unfortunately followed by sudden and sustained tragedy. Nineteen-year-old Clara suffered what physicians described as “puerperal convulsions,” or post-partum seizures, often called eclampsia. She died on May 15th, under the same roof that sheltered her festive wedding. William, no doubt heartbroken, walked up King Street to Magnolia Cemetery and purchased a small family plot.[30] Three weeks later, on June 6th, one of Clara’s infant daughters died of “marasmus,” or malnutrition, common for infants deprived of breastmilk in the era before synthetic formulas. The other infant girl apparently died around the same time, though a record of her death cannot be found. Months later, the distraught father erected a small marble tombstone at Magnolia Cemetery for his late wife and their two “infant babes.”[31]

William Ah Sang continued to reside and work in Charleston after the death of his young wife and daughters, but few records of his existence now survive. In the Federal Census of 1880, his name was rendered as “Ah Shang,” which likely represents the pronunciation he used. The 1880 census also confirms the presence of eight other persons of Chinese ancestry residing within the City of Charleston at that time. Sang Charles Ching, also known as Charlie Ching Chang, was the proprietor of a grocery store and shared a home with his wife’s White family, while Robert Links was a vendor of fruit and lived with his wife’s Mulatto family.[32]

The Links family left Charleston soon after the census of 1880, as did the city’s first and loneliest Chinese resident. William Ah Sang, aged thirty-two, died of consumption on the 18th of August, 1881. For nine years he had been the superintendent of the tea department at the Charleston Teapot, and the grateful Wilson brothers probably accompanied the body of their “faithful and efficient” colleague to his gravesite in Magnolia Cemetery. A brief obituary in the Charleston News and Courier stated regretfully that his family in China “will be notified of his death.”[33]

William Ah Sang did not live to witness the United States government’s ratification of the Chinese Exclusion Act in the spring of 1882. As in the years preceding his arrival in South Carolina, a rising tide of anti-immigrant fervor induced American legislators to close the nation’s borders to Asians of all description. The number of Chinese residents in Charleston County grew very slowly over the next century, and those who did come settled within the confines of urban Charleston rather than the fields and forests as imagined by the speculators of 1869. The Charleston Teapot persevered as a fashionable grocery store into the twentieth century, but the death of Samuel Wilson in 1909 sapped its focus and the business declared bankruptcy in the summer of 1914.[34]

There are no monuments or markers for William Ah Sang in the place he called home for nearly a decade, and some might argue that he achieved nothing remarkable during his short life. Consider, however, that he was one of the many brave people who ignored imaginary barriers invented by narrow-minded people and ventured farther afield than the majority of his peers. He was a humble clerk at a shop on King Street and endured tragic heartbreak, but he shared his passion for tea with his customers and brightened the lives of many Charlestonians during his brief sojourn here. At a time when most Americans feared or loathed the very idea of Asian people they had never encountered, Ah Sang projected a friendly smile and congenial manner that that eroded prejudice. For that small triumph, I make a pot of tea and pour out a cup for William Ah Sang.

[1] According to the Federal Census of 1870, the total population of South Carolina was 705,606 people, of whom 414,815 (or nearly 59%) were of African descent. The total population of Charleston County was 88,863 people, of whom 68% were of African descent. More than half of the county’s population (48,956) lived within the city of Charleston, where persons African descent formed 53% of the urban population.

[2] Andrew Gyory, Closing the Gate: Race, Politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 34.

[3] Charleston Daily Courier, 7 July 1869, page 2, “Chinese Immigration and the Problem of Labor.”

[4] Daily Courier, 19 July 1869, page 4, “The Labor Question.”

[5] Daily Courier, 17 July 1869, page 4, “South Carolina Agricultural and Mechanical Society”; Daily Courier, 26 July 1869, page 2, “The Proposed Chinese Agricultural Labor.”

[6] Daily Courier, 4 May 1870, page 2, “Agricultural and Immigration Convention.”

[7] Daily Courier, 5 May 1870, page 2, “The Agricultural and Immigration Convention”; Charleston Daily News, 6 May 1870, page 3, “The Convention.”

[8] Daily Courier, 11 May 1870, page 2, “Chinese Immigration.” The emphasized words appear in italics in the original source.

[9] For more information about the debate surrounding Chinese immigration to the Southern States, see Lucy Cohen, Chinese in the Post-Civil War South: A People without History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984); and Moon-Ho Jung, Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Sugar in the Age of Emancipation (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006).

[10] For more information about the availability of ice in nineteenth-century Charleston, see Charleston Time Machine Episode No. 49 and No. 238.

[11] This biographical information is extracted from Federal Census records and his obituary in Charleston News and Courier, 24 May 1909, page 5, “Samuel H. Wilson.” An image of Wilson’s tombstone is available on findagrave.com.

[12] Daily News, 14 April 1870, page 3, “Have you tried my Dollar Tea?”

[13] Daily News, 17 January 1871, page 2, “Copartnership Notices”; Daily News, 6 May 1871, advertisements on pages 2, 3; Daily News, 8 May 1871, page 1, “Wilson’s Grocery.” The property was known as No. 306 King Street during the 1870s, but became No. 284 during the city’s mass renumbering of street addresses in the months preceding the earthquake of 31 August 1886.

[14] Daily News, 6 May 1872, page 2, “Free Tea and Coffee”; Daily Courier, 20 July 1872, page 3, “Great Reduction in the Price of Tea”; Daily News, 10 August 1872, page 4, “The Tea Question.”

[15] Daily News, 9 August 1872, page 1, “Local Laconics.”

[16] Daily Courier, 14 November 1872, page 1, “Wilson’s Grocery.”

[17] News and Courier, 16 July 1873 (Wednesday), page 4, “Marine News.”

[18] News and Courier, 16 July 1873, page 4, “A Live Chinaman.”

[19] Jian Li, “A History of the Chinese in Charleston,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 99 (January 1998): 38.

[20] News and Courier, 16 July 1873, page 2, “To the Public.”

[21] News and Courier, 18 July 1873, page 2, “Teas! Teas! Teas!”

[22] The first advertisement under the new name appears in News and Courier, 16 August 1873, page 2.

[23] Oqui Adair probably resided in Charleston for several months after he and the Townsend family evacuated from Edisto Island in late 1861, but the duration of their tenure in the city is unknown. Additionally, a Chinese-born dropout from a Pennsylvania college, identified as Wong Sa Kee, gave a single public lecture on Chinese culture in Charleston in June 1870, “habited in his full national costume”; see Daily News, 3 June 1870, page 2, “Novel and Instructive Lecture.” For biographical information about Wong, see Scott D. Seligman, The First Chinese American: The Remarkable Life of Wong Chin Foo (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013).

[24] News and Courier, 16 August 1873, page 2, “Teas! Teas! Teas! Teas!”

[25] The earliest use of this advertising image appears in News and Courier, 1 July 1874, page 3. A reduced and simplified version of this same image appeared in advertisements for the Charleston Teapot as late as the spring of 1914; see Charleston Evening Post, 16 February 1914, page 5, “At the Teapot.”

[26] Advertisements for the Charleston Teapot used this phrase repeatedly during the 1870s; see, for example, News and Courier, 21 September 1875, page 4.

[27] An overview of Wilson’s business and a description of the teapot appears in News and Courier, 23 July 1875, page 4, “An Enterprising Grocery House.” The precise date of the erection of the large teapot is unknown, but the advertising phrase “Sign of the Teapot” first appears in News and Courier, 1 August 1874, page 3.

[28] News and Courier, 13 April 1874, page 1, “A Panorama of China.”

[29] News and Courier, 16 August 1875, page 4, “Talk About Town”; News and Courier, 19 August 1875, page 4, “Celestial Bliss.”

[30] According to the Return of Deaths within the City of Charleston (held in the Charleston Archive at CCPL), Mrs. Clara Ah Sang, a nineteen-year-old white, female, native of the City of Charleston, died at 2 College Street on 15 May 1876 of “puerperal convulsions” and was buried at Magnolia Cemetery. Clara’s death certificate is found on microfilm in the S.C. History Room at CCPL, and online through Ancestry.com.

[31] According to the Return of Deaths within the City of Charleston (held at CCPL), an “infant” female child of William Ah Sang, one month old, died of “marasmus” on 6 May 1876 at 4 College Street and was buried at Magnolia Cemetery. An illegible death certificate for an unnamed infant of William Ah Sing is available on microfilm in the S.C. History Room at CCPL, and online through Ancestry.com The extant tombstone at Magnolia Cemetery, viewable in findagrave.com, includes the name and death date of Clara Ah Sang, as well as the names of “her infant babes Clara and Martha.”

[32] Li, “A History of the Chinese in Charleston,” 37–38.

[33] News and Courier, 20 August 1881 (Saturday), page 1, “The Death of Ah Sang.”

[34] The façade of No. 284 King Street was modified in 1948 according to a Neoclassical design by Charleston architect Augustus Constantine; see News and Courier, 4 April 1948, page 1-C, “Remodeled Bank Building.” The building underwent significant renovations in 2022–23, including the installation of new store-front windows that erased the changes made in 1948. The present façade more closely resembles the building’s nineteenth-century appearance.

NEXT: Sullivan’s Island: Property of the Crown and State, 1663–1953

PREVIOUSLY: The Hard: Colonial Charleston’s Forgotten Maritime Center

See more from Charleston Time Machine