Who Were the Best “Charlestoners” in Jazz-Age Charleston?

Processing Request

Processing Request

The popularity of the new “Charleston” dance spread across the nation in 1925, but critics in the city of its birth generally held the fad at arm’s length. The invitation to participate in a national dance contest convinced local leaders to embrace the phenomenon, however, and Charleston sprang into action to capitalize on the marketing potential. Through a series of segregated contests in early 1926, the white community judged candidates to determine the city’s best Charleston-dancing couple. The youthful winners, accompanied by a municipal entourage, then raced to Chicago to receive a royal welcome.

The dance known as the “Charleston” was at the zenith of its popularity during the mid-1920s. Young men and women across the nation were fascinated by its swiveling steps and flapping arms that paired so well with the syncopated, unorthodox jazz music of that era. The conservative white mainstream of Charleston, South Carolina, was a bit slow to embrace the dance, however, despite the fact that many thousands of Americans were talking about the sleepy Southern seaport from which the dance purportedly arose. This national chatter constituted potential advertising for Charleston, of course, and city leaders finally awoke to the marketing potential in the autumn of 1925. An editorial in the Charleston Evening Post that August, for example, suggested that the local convention bureau should encourage teachers of dancing across the nation to come to this city to “study the dance in its native habitat.” Civic organizations should find the most proficient local “Charlestoners” and hire them to give exhibitions for visiting tourists. In whatever manner, said the Evening Post, locals should make every effort to “capitalize” on the latest dance sensation and, above all, “make it pay.”[1]

Then, at the beginning of December 1925, Charleston’s Chamber of Commerce received an unsolicited telegram from commercial affiliates in the Midwest. Its brief text conveyed unexpected news that set in motion a series of events that captivated the city’s attention during the ensuing winter:

“Trianon ballroom, Chicago, the most beautiful in the world, will hold a national amateur championship for Charleston dancers the first week in February. The opinion prevails this dance originated with you. Whether it did or not, this contest offers wonderful possibilities for publicity for Charleston. Would like to have you represented by dancing team. Will have your mayor [as] Chicago’s guest for finals.”

Members of the city’s Chamber of Commerce were initially perplexed by this generous invitation, which they shared with City Hall, the tourist and convention bureau, and the local media. “Doubtless it would help the project considerably if a team from Charleston went to the scene,” opined the Charleston Evening Post, “but a matter of such grave importance as this demands deliberation.” Most Americans believed that the dance originated here in the Palmetto City, so it follows that those same Americans probably assumed everyone in Charleston was an expert “Charlestoner.” “Would a team from Charleston,” pondered the Evening Post, “competing with experts from other cities, succeed in dispelling that opinion? Would it be harmful publicity to have Charlestoners direct from the factory defeated by exotic performers of the cold, bleak, north? That is, assuming that local Charlestoners would go down to defeat.” Putting self-doubt aside for the moment, the newspaper began to warm to the idea of participating in the national contest. “If there are any Charlestoners here—a point it would be interesting to ascertain—there should be nothing to keep them from going to Chicago and trying their skill—or whatever the dance calls for.”[2]

Members of the city’s Chamber of Commerce were initially perplexed by this generous invitation, which they shared with City Hall, the tourist and convention bureau, and the local media. “Doubtless it would help the project considerably if a team from Charleston went to the scene,” opined the Charleston Evening Post, “but a matter of such grave importance as this demands deliberation.” Most Americans believed that the dance originated here in the Palmetto City, so it follows that those same Americans probably assumed everyone in Charleston was an expert “Charlestoner.” “Would a team from Charleston,” pondered the Evening Post, “competing with experts from other cities, succeed in dispelling that opinion? Would it be harmful publicity to have Charlestoners direct from the factory defeated by exotic performers of the cold, bleak, north? That is, assuming that local Charlestoners would go down to defeat.” Putting self-doubt aside for the moment, the newspaper began to warm to the idea of participating in the national contest. “If there are any Charlestoners here—a point it would be interesting to ascertain—there should be nothing to keep them from going to Chicago and trying their skill—or whatever the dance calls for.”[2]

In mid-December, a representative of the planned Chicago event came to Charleston to encourage the city to send representatives to the national contest. Meeting with various local officials, he explained that cities across the country were signing up to participate, and the contest would feature dancers exhibiting the “diversified mannerisms that characterize the mode of teaching this dance in various parts of the country.” Each city will select one representative couple through a series of local elimination rounds. All of the local champions then will travel to Chicago, with chaperones, to compete in semi-final and final contests on February 8th and 9th, 1926. The competition will be judged by experts of national renown and all the participants will receive “worthwhile prizes.”[3]

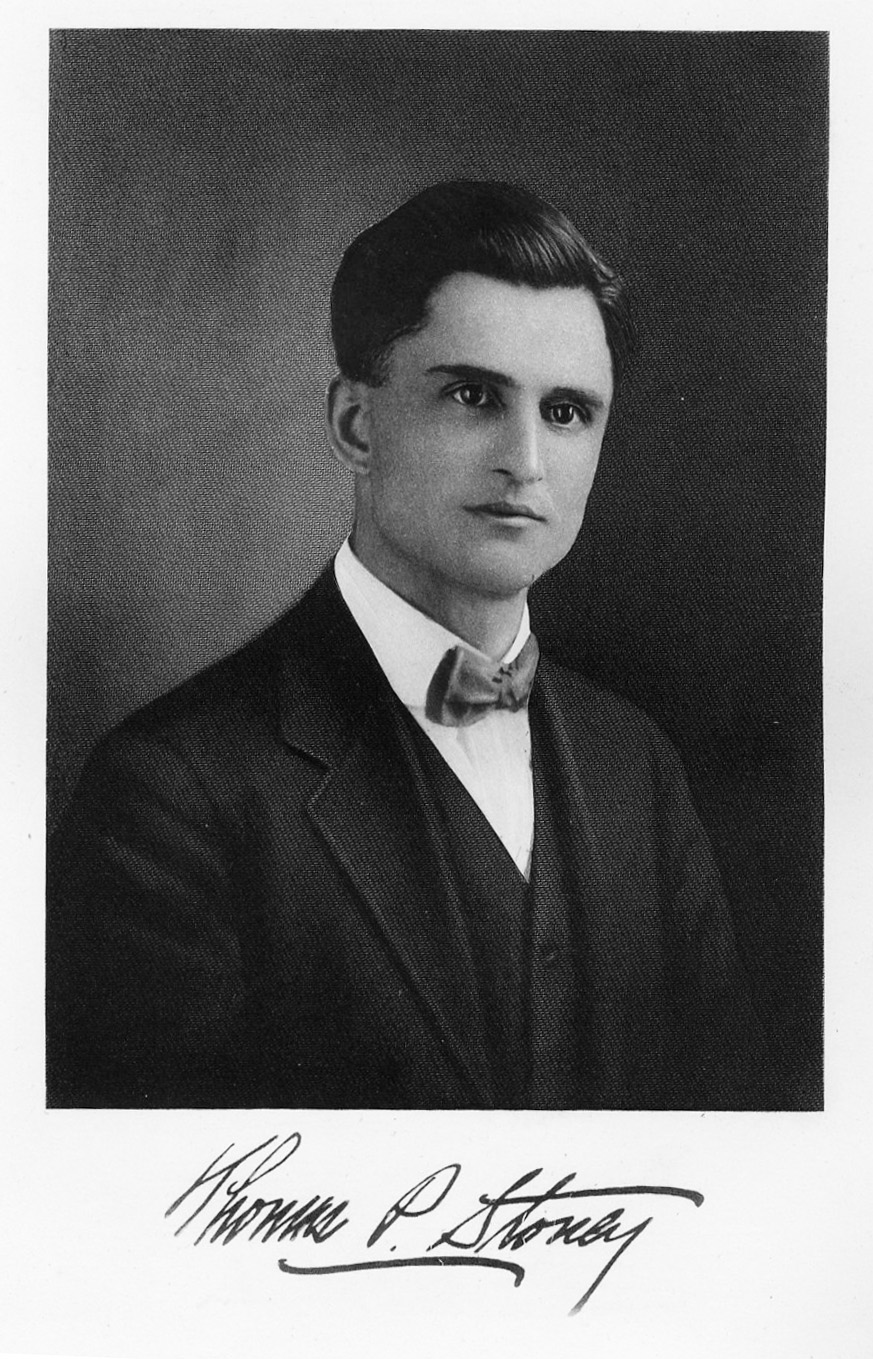

Around the turn of the new year, Charleston’s mayor, Thomas P. Stoney (1889–1973), and local businessmen negotiated with the organizers of the Chicago event to ensure it would be worth the effort to participate. The organizers wanted the City of Charleston to participate in some form to lend a bit of credibility to the ostensibly national competition. The local tourism and convention bureau advised the mayor that the widespread popularity of the “Charleston” dance put the City of Charleston in a “unique position” to benefit from a large volume of priceless national publicity. After much deliberation on Broad Street, city leaders finally decided to accept the invitation and to send a local delegation to participate in the national event. “Regardless of the merits of the dance,” reported the Evening Post, “the new step has been tremendously popular, and is in vogue through this country and elsewhere. Whether or not it is actually the case, the origin of the dance is accredited to Charleston, and it is because of this that the Trianon [ballroom] is particularly anxious to have this city represented.”

In exchange for a commitment from the City of Charleston, the organizers of the Chicago contest agreed to feature the Charleston delegation as guests of honor, to facilitate ample publicity “of a desirable and beneficial sort” during the contest, and to permit the mayor to make a national radio address at the event. On January 2nd, 1926, the local media announced that the city would indeed participate in the national “Charleston” contest in Chicago, some five weeks in the future. The tourist and convention bureau had formed a committee, headed by businessman Sam Berlin, to organize the local campaign. In the coming weeks, the committee would host a series of five preliminary competitions to select the best Charleston-dancing couple in the city.[4]

In January of 1926, many Charlestonians were hustling to catch up with the dance craze that most of the country had already embraced. Hollywood silent film stars like Colleen Moore, for example, raved about the “Charleston” and how she enjoyed dancing it in her exciting new film, We Moderns, for which she had learned all the latest “freak dances.” Miss Moore acknowledged that the “Charleston” certainly wasn’t prim, but the screen maven argued that it was sufficiently proper to merit general respect. “The Charleston is animate jazz music,” she said, and it was “wonderful exercise” as well. Although Colleen Moore believed New Orleans “darkies” had created the “Charleston” by adapting a Hispanic dance, she embraced it warmly. “If anything is American,” she said, “the Charleston is.”[5]

In January of 1926, many Charlestonians were hustling to catch up with the dance craze that most of the country had already embraced. Hollywood silent film stars like Colleen Moore, for example, raved about the “Charleston” and how she enjoyed dancing it in her exciting new film, We Moderns, for which she had learned all the latest “freak dances.” Miss Moore acknowledged that the “Charleston” certainly wasn’t prim, but the screen maven argued that it was sufficiently proper to merit general respect. “The Charleston is animate jazz music,” she said, and it was “wonderful exercise” as well. Although Colleen Moore believed New Orleans “darkies” had created the “Charleston” by adapting a Hispanic dance, she embraced it warmly. “If anything is American,” she said, “the Charleston is.”[5]

Not everyone was so pleased with the new dance sensation, however. Some youthful exponents carried its carefree, loose-limbed movements to unprecedented extremes, resulting in a dance that appeared to conservative viewers like the epitome of uninhibited sensual decadence. The fact that it had been created by Americans of African descent also contributed to prejudice against the dance. Some white Americans, especially in the Southern states, felt that the color of its cultural roots rendered the “Charleston” inherently undesirable. When South Carolina’s conservative governor, Thomas G. McLeod, traveled to Boston to give a speech in January 1926, for example, he was infuriated by reporters who pestered him with questions about the roots of the “Charleston” dance in the Palmetto State. Speaking at a Bible convention in downtown Charleston the following week, Governor McLeod condemned the public fascination with the popular dance about which he delivered an “emphatic denunciation.” The steps now called the “Charleston” had indeed been “very popular among the negroes” of South Carolina in the 1890s, said the governor, but times had changed and now “even they had become too respectable to dance it.”[6]

Following the governor’s scathing attack on the “Charleston,” of which many Northern newspapers took note, the mayor of Charleston immediately spoke up in its defense. Thirty-six-year-old Thomas P. Stoney, affectionately known to the local press as “Tommie,” told reporters that the dance was “all right” with him, and assured the public that he would never sanction or promote a dance that reflected poorly on his dear “city by the sea.” Besides, the national obsession with the “Charleston” dance was generating an immeasurable bounty of free advertising for the city. If anyone in the United States had reservations about the wholesome nature of the popular dance, said Mayor Stoney, they should come to Charleston themselves to see the dignified manner in which real Charlestonians performed it.[7]

Before selecting one couple to represent Charleston at the Trianon ballroom in Chicago, the organizing committee sponsored a series of four preliminary contests on January 13th, 19th, 21st, and 28th. The first three of these events were held at a venue then called Ashley Park, at the east end of Heriot Street (owned by the Charleston Rifle Club), while the fourth was held at Hibernian Hall (105 Meeting Street).

The publicity campaign promoting these dance contests in the local media repeatedly described them as wholesome community events that were open to everyone. In fact, however, they were open only to approximately half of Charleston’s urban population of 70,000 people. The “Charleston” competitions of 1926 were white-only events at which citizens of African ancestry were not welcome to compete or attend. None of the advertisements or promotional descriptions of the local competitions needed to articulate such restrictions, of course, because they formed part of the “Jim Crow” practices common in Southern states at that time. In these dance contests, like the rest of Southern culture and politics in the early twentieth century, black and white citizens tacitly observed an invisible but legally mandated color line that separated their respective lives. Although no documentary evidence exists today, I suspect that the negotiations between Charleston and the organizers of the Chicago contest included assurances that negroes would not be allowed to participate in the Windy City tournament. The dominant white community here was happy to appropriate creative works like the “Charleston” from their black neighbors and then retain to themselves the accolades and rewards they produced.

The publicity campaign promoting these dance contests in the local media repeatedly described them as wholesome community events that were open to everyone. In fact, however, they were open only to approximately half of Charleston’s urban population of 70,000 people. The “Charleston” competitions of 1926 were white-only events at which citizens of African ancestry were not welcome to compete or attend. None of the advertisements or promotional descriptions of the local competitions needed to articulate such restrictions, of course, because they formed part of the “Jim Crow” practices common in Southern states at that time. In these dance contests, like the rest of Southern culture and politics in the early twentieth century, black and white citizens tacitly observed an invisible but legally mandated color line that separated their respective lives. Although no documentary evidence exists today, I suspect that the negotiations between Charleston and the organizers of the Chicago contest included assurances that negroes would not be allowed to participate in the Windy City tournament. The dominant white community here was happy to appropriate creative works like the “Charleston” from their black neighbors and then retain to themselves the accolades and rewards they produced.

Participation in the local dance contests of early 1926 was further restricted to amateur dancers residing within the incorporated limits of peninsular Charleston. Aspiring young dancers living west of the Ashley, east of the Cooper, or on any of the neighboring islands were excluded. Entries in each of the four preliminary rounds was even further restricted by ward within the City of Charleston. The first contest, held on January 13th, was open to male residents of wards 1, 3, and 5 (the lower east side), although their female partners could hail from any of the city wards. Similarly, the second event included male dancers from city wards 2, 4, and 6 (the lower westside), then wards 7, 9, and 11 (the upper east side), and finally wards 8, 10, and 12 (the upper west side).

The local competitions took place with the context of public dances lasting from 9 p.m. to 2 a.m., with an hour set aside before midnight for the competition. There was no registration fee for competitors and no admission fee for ladies, but every gentlemen attending one of these dances had to pay one dollar. Music for the entire series was provided by a popular local dance band headed by John Skuhra (1891–1968), a native of Bohemia. Normally a seven-piece band, “Skuhra’s Orchestra,” as it was known, added three horns to increase their volume. The competitors were judged by two established dance teachers, Mayme Forbes and Saidee Brown, and a talented young semi-pro named Jack Simmons, who occasionally performed “Charleston” exhibitions at the Isle of Palms pavilion. At each of the preliminary rounds, Mayor Stoney attended and explained the purpose of the competition and encouraged participants to put their best foot forward.

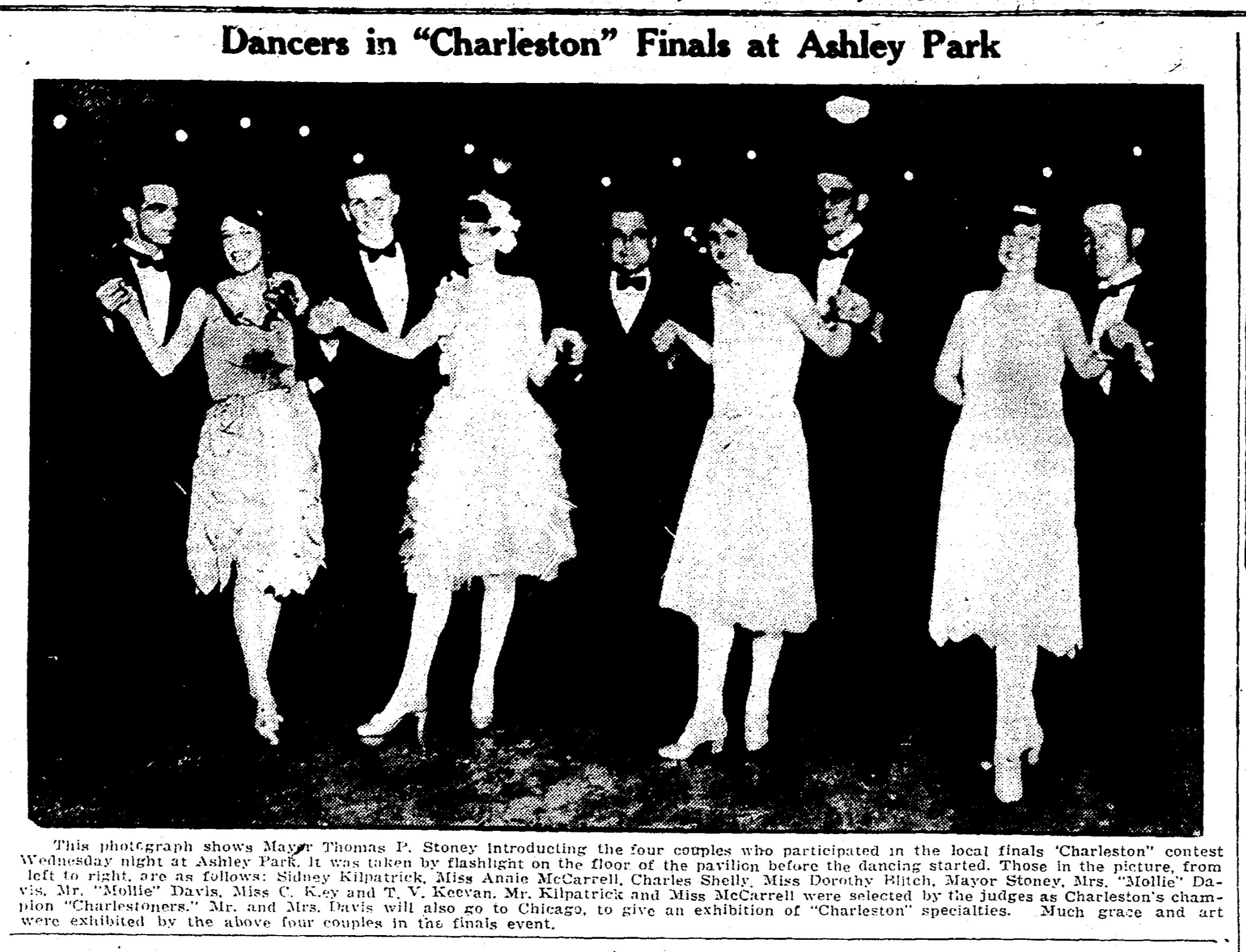

From each of the first four preliminary contests, the judges selected one winning couple. At the end of January, four couples were preparing for a show-down: Thomas V. Keevan paired with Miss (Mary) Clementine Key; G. E. Rhett Davis, better known as “Mollie” Davis, and his young wife, Edith; Sidney Kilpatrick and Miss Annie McCarrel; and finally Charles Shelly and Miss Dorothy Blitch.[8]

On the evening of Wednesday, February 3rd, these eight competitors returned to Ashley Park for a final elimination contest. For this event, which was addended by approximately 2,500 spectators, the organizing committee charged admission for ladies and children as well as men. The crowd was so large that the police department called in motorcycle officers to control the traffic leading to and from the venue. Within the dance hall, the crowd was so large that organizers had to summon the traffic cops to help clear the dance floor for the competition portion of the evening. Mayor Stoney made a brief address before the finalists took the stage, reminding the audience that the purpose of sending a representative couple to Chicago was “to demonstrate that the dance named after this city and which is supposed to have originated here is not a [poor] reflection on the traditions of the City by the Sea.”

As with the earlier rounds, the four competing couples were required to demonstrate two contrasting styles of dance: the ballroom “Charleston,” which emphasized grace and poise, and the “stage or eccentric” version that showcased originality and physical skill. The dancers were attired in tuxedos and tasteful knee-length frocks for the ballroom competition, then changed into casual wear for the “eccentric” portion of the evening. After they had all made their displays, each couple dancing each style for five minutes, the competitors withdrew from the spotlight. The audience concluded that the local dancers had all performed their steps, even the “eccentric” ones, with grace and propriety. “If there is anything at all about the dance that is objectionable,” stated one reporter, “it was not in the performances at Ashley Park.” Around midnight, after a long and difficult deliberation, the judges selected Annie McCarrel (aged 20) and Sidney Kilpatrick (aged 19) as Charleston’s best (white) amateur “Charlestoners.” The excited crowd roared with joy and gave the winners a “tremendous ovation.”[9]

As with the earlier rounds, the four competing couples were required to demonstrate two contrasting styles of dance: the ballroom “Charleston,” which emphasized grace and poise, and the “stage or eccentric” version that showcased originality and physical skill. The dancers were attired in tuxedos and tasteful knee-length frocks for the ballroom competition, then changed into casual wear for the “eccentric” portion of the evening. After they had all made their displays, each couple dancing each style for five minutes, the competitors withdrew from the spotlight. The audience concluded that the local dancers had all performed their steps, even the “eccentric” ones, with grace and propriety. “If there is anything at all about the dance that is objectionable,” stated one reporter, “it was not in the performances at Ashley Park.” Around midnight, after a long and difficult deliberation, the judges selected Annie McCarrel (aged 20) and Sidney Kilpatrick (aged 19) as Charleston’s best (white) amateur “Charlestoners.” The excited crowd roared with joy and gave the winners a “tremendous ovation.”[9]

After the final local competition ended in the wee hours of Thursday morning, the contestants had only a few days to prepare for the national stage. The national competition in Chicago commenced on the evening of Monday, February 8th, so the Charleston winners had to board a north-bound train on the evening of Saturday the 6th. While the dancers packed their costumes and perfected their choreography, the chairman of the organizing committee, Sam Berlin, expanded the list of local representatives. He felt the competition on February 3rd had been so close, and the coming event in Chicago so important, that it might be wise to invite additional dancers to provide some extra advertising for the city. Income from entrance fees to the five local dance contests had generated thousands of dollars, so there was money in hand to cover the added expense. Agreeing with the chairman, the committee invited “Mollie” and Edith Davis to journey with them to Chicago, where their excellent renditions of energetic “stage or eccentric” dancing could entertain the audience and national reporters preceding the official competition.

At dusk on Saturday, February 6th, the Charleston delegation gathered at Union Station, at the east end of Columbus Street, to board a north-bound train. The party of twelve included Mayor Thomas P. Stoney and his wife, Beverly, Chamber of Commerce representative Sam Berlin and his wife, Bertie, Sidney Kilpatrick, Annie McCarrel and her mother, Elizabeth (as chaperone), “Mollie” and Edith Davis, dance coach Jack Simmons, and two local reporters. During the ensuing days, the local press reported the movements of this Charleston delegation with special interest and pride. The young dancers would give the nation a taste of the Lowcountry culture, while the mayor was going to promote the city through meetings with Chicago-area business men and a national radio address. City leaders in general recognized this event as a unique opportunity and negotiated with its promoters to secure for Charleston “a volume of advertising which would have cost many thousands of collars to secure by other means.”

In his much-anticipated radio address, said the editors of the Evening Post, “the mayor will use the opportunity to spread the story of Charleston, its historic interest, its commercial facilities, its attractions to home-seekers, at the same time he interprets the significance of the dance and gives [the] official version of its origin. . . . The world will learn that Charleston has much to offer and many who come to dance will remain to develop.”[10]

The train carrying the Charleston twelve arrived at Washington D.C. at 1:30 Sunday afternoon, where they were met by reporters and photographers from the capital and Baltimore press. After boarding a special Pullman car prepared just for the Charleston party, they proceeded westward to Pittsburg and then across the snow-covered Midwestern landscape to Chicago.

The train carrying the Charleston twelve arrived at Washington D.C. at 1:30 Sunday afternoon, where they were met by reporters and photographers from the capital and Baltimore press. After boarding a special Pullman car prepared just for the Charleston party, they proceeded westward to Pittsburg and then across the snow-covered Midwestern landscape to Chicago.

The winter sky was dark gray and street lamps were burning when the train pulled into Chicago’s new Union Station on the morning of Monday, February 8th. Despite the bitter cold and heavy mist, the entire Charleston delegation found a warm welcome awaiting them as they stepped from the train. Flashbulbs popped continuously for several minutes as reporters mobbed the Lowcountry visitors and hounded them with questions. Photographers lined up the dignitaries on the platform in the train shed and snapped dozens of pictures for distribution across the country. Members of the City of Chicago’s official welcoming committee, headed by the mayor’s secretary, had to force their way through the throng of reporters to greet the Charlestonians. Mayor William E. Deever was on his way back from a meeting in St. Louis but relayed the message that he looked forward to meeting Mayor Stoney tomorrow.

After receiving their official welcome and being escorted into the warm train station, the visitors posed for more photographs and questions. Curious bystanders awaiting outbound trains flocked to the scene to inquire about the ruckus. Dance competitors arriving from other cities joined the fray and added fuel to the media circus. Everyone wanted to have their picture taken with the Charleston Charlestoners and the wide-smiling, jovial mayor of the fabled city. They were all happy to oblige, of course, and Mayor Stoney was reportedly quite a hit with the crowd. He ignored questions about himself but was only too happy to talk about his home town. Officials from the Trianon ballroom eventually intervened and escorted the Charleston twelve through the admiring crowd to automobiles waiting in the street.

Moments later, they arrived at the Chicago Beach Hotel on the shore of Lake Michigan, where contest organizers welcomed them with colorful sashes and badges identifying them as guests of honor. Here they met the other fifty-odd contestants from twenty-seven other cities, most of whom were also just arriving from the train station. Mayor Stoney and Sam Berlin soon dashed off to a luncheon with local business leaders. With bags stowed in their respective rooms, the crowd of nearly a hundred young dancers and their chaperones gathered in the hotel dining room for a raucous lunch. Complements were exchanged, novel dance steps demonstrated, and new friends quickly made.[11]

After their long journey and energetic lunch, the Charleston competitors, Annie McCarrel and Sidney Kilpatrick, had just a few hours to relax before the competition began. The next few days would see a blur of frenetic activity, punctuated by brief moments of restless sleep. Tune in next week, when we’ll continue this jazz-age adventure by following Charleston’s best dancers through the nail-biting paces of both regional and national championships at the mammoth Trianon ballroom, and listen to Mayor Thomas P. Stoney tell the nation about his beloved city and the “official” history of the “Charleston” dance.

[1] Charleston Evening Post, 29 August 1925, page 10, “Make It Pay.”

[2] Evening Post, 3 December 1925, page 2, “Championship Charlestoner.”

[3] Evening Post, 16 December 1925, page 3, “‘Charleston’ Contest Plan.”

[4] Evening Post, 2 January 1926, page 13, “Charleston To Participate”; Evening Post, 5 January 1926, page 13, “Charleston Committee.”

[5] Evening Post, 30 January 1926, page 3, “Country is Charleston Mad, Says Colleen Moore.”

[6] Charleston News and Courier, 25 January 1926, page 2, “Governor Lauds Bible Teachings”; Evening Post, 25 January 1926, page 14, “Gov. M’Leod Lauds Bible.”

[7] Evening Post, 26 January 1926, page 1, “The ‘Charleston’ All Right In Opinion Mayor Stoney.”

[8] Evening Post, 11 January 1926 (Monday), page 2, “First Contest At Ashley Park”; News and Courier, 12 January 1926, page 2, “Contest to Pick City Champions”; Evening Post, 14 January 1926, page 3, “Preliminary Contest Held”; Evening Post, 18 January 1926, page 12, “Elimination Dance Tuesday”; Evening Post, 21 January 1926, page 10, “3rd Contest On Tonight”; Evening Post, 22 January 1926, page 5, “2 Additional Charlestoners”; Evening Post, 25 January 1926, page 12, “Preliminary On Thursday”; Evening Post, 27 January 1926, page 11, “Last of Four Preliminaries”; Evening Post, 28 January 1926, page 12, “Last Chance to Qualify.”

[9] Evening Post, 29 January 1926, page 13: “‘Charleston’ Finals Feb. 3”; Evening Post, 1 February 1926, page 2, “Finals Dance on Wednesday”; Evening Post, 2 February 1926, page 17, “All Invited Ashley Park”; News and Courier, 4 February 1926, page 2, “Winners Chosen in ‘Charleston’”; Evening Post, 4 February 1926, page 5, “To Represent Charleston.”

[10] Evening Post, 6 February 1926, page 4, “Big Publicity.”

[11] Evening Post, 5 February 1926, page 2, “Two Couples to Chicago”; Evening Post, 6 February 1926, page 2, “Chicago Trip for Dancers”; News and Courier, 8 February 1926, page 1, “‘Charleston’ Party Speeds On Its Way to ‘Windy City’”; News and Courier, 9 February 1926, page 1, “All Chicago Knows about ‘Charleston.’”

PREVIOUS: Bee Jackson Wanted to “Charleston” in Charleston in 1925

NEXT: Representing Charleston at the 1926 National “Charleston” Contest

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments