Vendue Range: A Brief History

Processing Request

Processing Request

Today we’re going to travel back in Lowcountry history to explore the roots of a site in urban Charleston called Vendue Range. Almost everybody who’s been to Charleston in the past twenty-odd years has probably visited Vendue Range, but the small site may not have made much of an impression besides serving as the path to the popular splash fountain in Waterfront Park. Most visitors are a bit confused by the street’s odd name, and I’ll bet very few locals know much about the origins of this Charleston landmark. As with everything in Charleston and our storied community, however, there’s actually an interesting, colorful tale about how it came to be. So let’s set our time machine back to the earliest days of Charleston and take a quick tour of the slow rise of Vendue Range, from a vacant tidal mudflat to a picturesque destination.

Let’s begin with the basics. Vendue Range is a short street that runs eastward about 450 feet from the east side of East Bay Street to Concord Street, at the edge of the Cooper River waterfront. The east end of Vendue Range terminates at a large fountain that forms one of the most popular features of Charleston’s Waterfront Park. In the early days of Charleston—actually for the first 130 years of the city, from 1680 to 1810—this street did not have a name because there was no street here. Originally it was a small tidal inlet that flowed west of East Bay Street at high tide. By the 1720s the western part of this inlet had been filled and the resulting thoroughfare was called Dock Street. Dock Street was officially renamed Queen Street in April of 1734, becoming the first of Charleston’s streets to have a legally sanctioned name. We could talk for hours about the muddy origins of Queen Street, but we’ll save that for a future program.

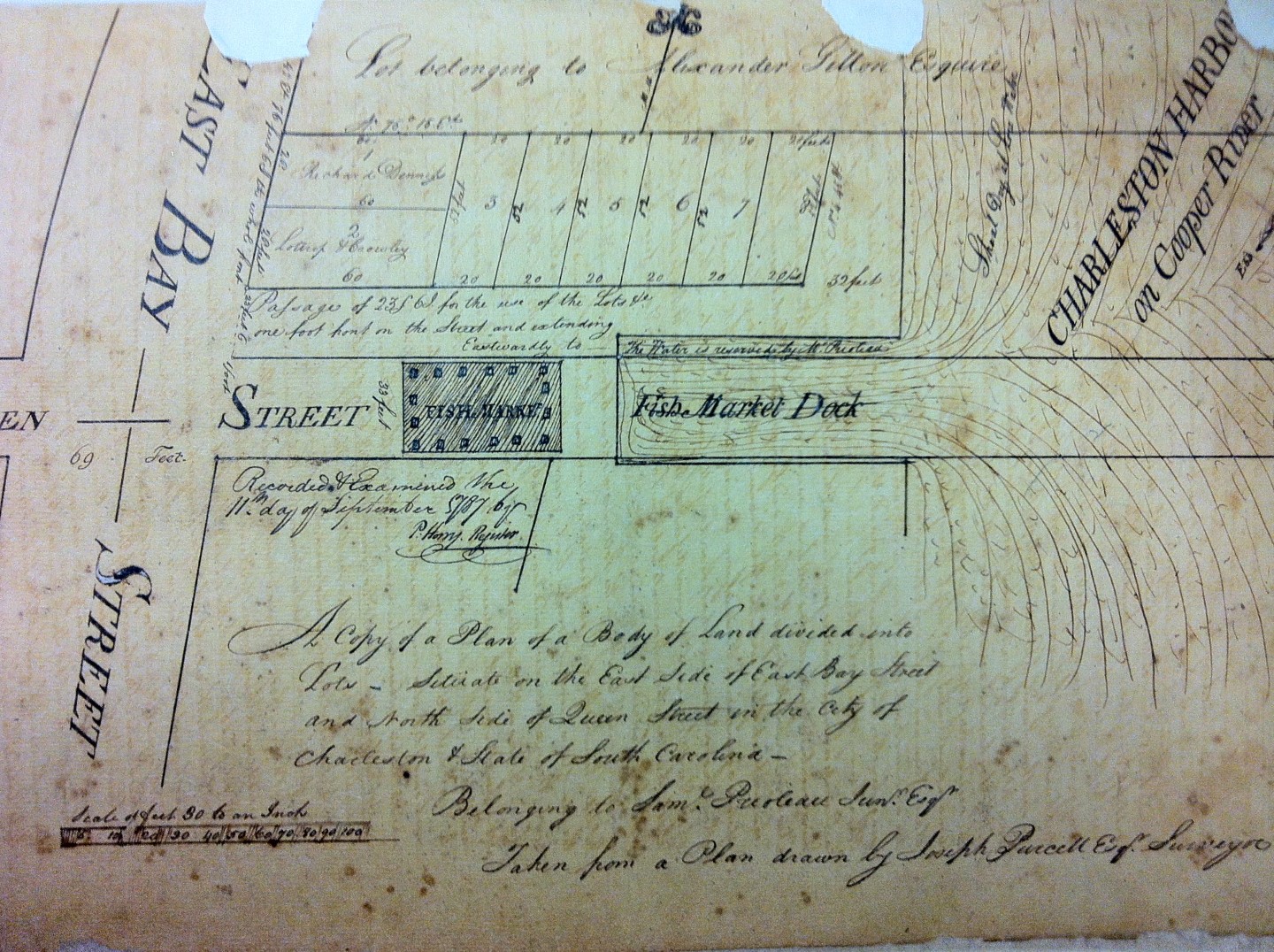

After 1734, the site we now call Vendue Range was commonly called “the east end of Queen Street.” It was simply a vacant mud flat that was underwater at high tide. By the middle of the eighteenth century, there were wharves on the north and south sides of this open mudflat, and the Prioleau family came to own all of the property in question. In 1770, the South Carolina legislature ratified an act to create an official fish market for Charles Town and funded the construction of a relatively small shed at the east end of Queen Street. The shed was set back a sufficient distance eastward from East Bay Street so that small, undecked boats could deliver fresh fish directly to the shed at high tide.

In 1787, a few years after the end of the American Revolution, the new city government of Charleston negotiated with the Prioleau family to use part of this property as a vegetable market for the city’s rapidly expanding population. During the 1787 landscaping project to create a broad open space for the vegetable market, the city also created a slip for the landing of Mr. Hibben’s ferry that connected Charleston with Christ Church Parish, the area on the east side of the Cooper River we now call Mt. Pleasant. When President George Washington paid a visit to Charleston in May of 1791, he arrived from Christ Church Parish by water at Prioleau’s wharf, at the southeast end of Queen Street. According to the newspapers of that time, it was a triumphal moment with thousands of spectators, music, and banners waving, but President Washington had to step from the ferry slip past the city’s fish market and through a dusty, open area with tables selling fruits and vegetables. Perhaps the president didn’t get the best first impression of Charleston.

In 1787, a few years after the end of the American Revolution, the new city government of Charleston negotiated with the Prioleau family to use part of this property as a vegetable market for the city’s rapidly expanding population. During the 1787 landscaping project to create a broad open space for the vegetable market, the city also created a slip for the landing of Mr. Hibben’s ferry that connected Charleston with Christ Church Parish, the area on the east side of the Cooper River we now call Mt. Pleasant. When President George Washington paid a visit to Charleston in May of 1791, he arrived from Christ Church Parish by water at Prioleau’s wharf, at the southeast end of Queen Street. According to the newspapers of that time, it was a triumphal moment with thousands of spectators, music, and banners waving, but President Washington had to step from the ferry slip past the city’s fish market and through a dusty, open area with tables selling fruits and vegetables. Perhaps the president didn’t get the best first impression of Charleston.

At the time of Washington’s brief visit to Charleston in 1791, the city government was actually in the midst of a campaign to consolidate its market places, which were distributed among three different locations. If you were looking to purchase fresh beef, for example, you visited the Beef Market, which had stood at the northeast corner of Broad and Meeting Streets since the late 1730s. If you wanted to purchase “small meats” such as lamb or pork, you went to the Lower Market at the east end of Tradd Street. Fish, fruits, and vegetables, as you now know, were being sold at the east end of Queen Street. The city’s desire to consolidate these activities was hampered by the lack of sufficient public space, however, so a public-private partnership was required. In the spring of 1788 Charleston’s City Council received a deed of gift from six property owners around a creek or tidal inlet on the northeast side of town, the site we now call Market Street. In exchange for the free land, the city agreed to fill the muddy site and to build sheds for the sales of all sorts of foodstuffs. This was a great bargain for the city, but there was a reversion clause. If the city ever ceased to use the land as a market place, the property would revert to its original six owners.

After a year or so of filling and landscaping, in 1789 the city opened a 200-foot long brick beef market in the newly created Market Street. A similarly sized vegetable market was in the works when the city’s market plans were put on hold. In late 1793, in the wake of a slave revolt in the island nation of Saint Domingue (now Haiti), the city government of Charleston transformed the new beef market into public housing for French refugees. The Market Street property ceased to be used as a market, and the land reverted to the six proprietors who had given it to the city in 1788. In 1794 the sale of beef returned to the old Beef Market at the corner of Broad and Meeting Streets, and market life returned to the familiar patterns of the 1780s.

In the summer of 1796 the logistics of Charleston’s urban market suffered another setback when a neighborhood fire destroyed the old Beef Market, where City Hall stands today. Of necessity, then, the small Lower Market at the east end of Tradd Street became the city’s market place for all sorts of flesh, as they called it. That site was entirely too crowded, however, so Charleston’s City Council again negotiated with the Prioleau family to use even more of the low-lying land at the east end of Queen Street. Between 1797 and 1799 the city constructed a brick market shed at the site to accommodate the sale of meat at this site, in addition to the existing shed for the sale of fish and the stalls for the selling of fruits and vegetables. When the new Beef Market finally opened for business in December of 1799, the Lower Market at the east end of Tradd Street was officially closed. At the turn of the nineteenth century, therefore, the relatively small piece of land at the east end of Queen Street became the city’s only public market place.

It didn’t take the city very long to figure out that the constrained waterfront site at the east end of Queen Street was too small for Charleston expanding population. In the autumn of 1805 city leaders went back to the negotiating table with the owners of property in an around what we now called Market Street. They had donated a large swath of land to the city in 1788, but the property reverted to the original owners after the city used the land to house Haitian refugees rather than as a market place. After reaching a new agreement to re-start the Market Street venture in 1805, the city resumed the tedious process of filling that low-lying site and building new market sheds. After nearly two years of construction, the city’s new market in Market Street officially opened on the first day of August 1807, and the sale of meat, fruit, and vegetables at the east end of Queen Street immediately stopped. A new fish market was then built at the east end of Market Street, and the old fish market at the east end of Queen Street, constructed in the early 1770s, officially closed on the last day of October 1807.

During the years 1808 and 1809, Charleston’s City Council worked with the Prioleau family, who had gifted the land at the east end of Queen Street to the city, to demolish the old market sheds and haul in hundreds of cords of wood to fill the low-lying site to slightly drier elevation. What was once a mudflat became an unpaved public thoroughfare seventy-two feet wide. Along the north and south sides of this short, un-named street arose “ranges” of new commercial buildings. These waterfront, wharf-side buildings weren’t designed for retail sales, however, but rather for vendue sales.

“Vendue” is an old English word for sales at public outcry, or auction, and the term was regularly used in Charleston from the earliest days of the town. Enslaved people and real estate were traditionally sold at vendue in urban Charleston in the shade of the north side of the Exchange building, but vendue masters (as auctioneers were known) also conducted smaller, less formal sales, what we might call “estate sales” or “flea markets” in which small household items were “knocked down” to the highest bidder. In the early years of the nineteenth century, the city of Charleston used its partnership with the Prioleau family at the east end of Queen Street as an opportunity to create a new, clustered home for small vendue sales. The site had been used as a public market place since the early 1770s, but now the site had been dressed up, re-landscaped, and the nature of the goods and sales was about to change.

The Charleston newspapers of late January 1810 contain the earliest known advertisements to sales taking place along the “new Vendue Range” at the east end of Queen Street. That name was used informally, perhaps even tentatively at first, but within a few years the phrase “Vendue Range” had become an accepted part of the Charleston lexicon. To improve the shopping experience at Vendue Range, the proprietors of the new vendue shops on the north and south sides of the seventy-two-foot-wide street began erecting broad fabric awnings to shade the customers who came to inspect goods laid out on tables in front of the shops. Soon the various awnings became a motley affair of different heights and breadths, and the simple act of strolling through the crowds in Vendue Range turned into a sort of obstacle course. After listening to a number of complaints from citizens, the city’s street commissioners worked with the vendue masters to devise a plan that would accommodate the needs of both public traffic and commerce. In January 1817 the commissioners of the streets resolved to plant two rows of posts running east-west along the length of Vendue Range, twenty-one feet away from the north and south sides of Vendue Range. This plan left an open street, thirty feet wide, in the center for traffic, and allowed vendue masters to erect broad awnings over protected sidewalks reserved for the display their auction wares.

The Charleston newspapers of late January 1810 contain the earliest known advertisements to sales taking place along the “new Vendue Range” at the east end of Queen Street. That name was used informally, perhaps even tentatively at first, but within a few years the phrase “Vendue Range” had become an accepted part of the Charleston lexicon. To improve the shopping experience at Vendue Range, the proprietors of the new vendue shops on the north and south sides of the seventy-two-foot-wide street began erecting broad fabric awnings to shade the customers who came to inspect goods laid out on tables in front of the shops. Soon the various awnings became a motley affair of different heights and breadths, and the simple act of strolling through the crowds in Vendue Range turned into a sort of obstacle course. After listening to a number of complaints from citizens, the city’s street commissioners worked with the vendue masters to devise a plan that would accommodate the needs of both public traffic and commerce. In January 1817 the commissioners of the streets resolved to plant two rows of posts running east-west along the length of Vendue Range, twenty-one feet away from the north and south sides of Vendue Range. This plan left an open street, thirty feet wide, in the center for traffic, and allowed vendue masters to erect broad awnings over protected sidewalks reserved for the display their auction wares.

A year later, in early 1818, the City of Charleston began paving East Bay Street with stones imported from New York. This was Charleston’s first campaign to pave its sandy streets, and it included all of the commercial, waterfront area from Market Street on the north to Stoll’s Alley on the south. The plan did not include paving the wharfs, however, so the auctioneers in Vendue Range asked the city for a bit of help. In the summer of 1818 the city agreed to purchase extra stone from New York to pave Vendue Range, and the work was probably done in 1819 or a bit later. This ground at the east end of Queen Street was originally a tidal mudflat, however, and had been filled with trash and hundreds of cords of wood in a series of efforts between the early 1770s and 1809. So was the first effort to pave Vendue Range around the year 1820 successful? Such details are hard to find, so we’ll have to take the word of a correspondent who called himself simply “a Sailor” when he wrote the following brief communication to the Charleston Courier on 9 October 1829:

“If any man wants a pair of broken shins, I would advise him to walk down the North side of Vendue Range, on a dark night—and if he don’t get a pair, I will agree to break them for him for nothing.”

Charleston’s busy maritime waterfront evolved in the nineteenth century as larger steamships replaced the fishing boats and rowed ferries that used to dock at Vendue Range. As traffic increased, the old mudflat gradually filled up and the wooden wharves had to be extended further and further out into the Cooper River to receive vessels and passengers. Eventually the landing near the southeast end of Vendue Range became the home of the mighty Clyde Line of steamships that transported passengers to and from distant port cities. When the era of passenger traffic through this site ended in the middle of the twentieth century, Vendue Range and its abandoned, burnt-out wharves became part of the run-down fabric of a sleepy, depressed Charleston.

The revitalization of Vendue Range began during the administration of Mayor Joe Riley. In the late 1970s, the city developed a plan to rejuvenate this area by creating a waterfront park on the site of the old, silted-up wharves, using Vendue Range as the gateway to a new public green space. After years of planning and hard labor, the proposed park was nearly derailed by the arrival of Hurricane Hugo in September 1989. The city persevered and the work continued, however, and Charleston’s Waterfront Park formally opened in May of 1990. One of the park’s most popular features is the ring of jets that provide a canopy of cool, refreshing water to thousands of sun-baked tourists every year. I don’t know if the designers of this fountain were inspired by the old awnings that once shaded customers along the fringes of Vendue Range in the 1800s, but it seems a fitting allusion to me.

The revitalization of Vendue Range began during the administration of Mayor Joe Riley. In the late 1970s, the city developed a plan to rejuvenate this area by creating a waterfront park on the site of the old, silted-up wharves, using Vendue Range as the gateway to a new public green space. After years of planning and hard labor, the proposed park was nearly derailed by the arrival of Hurricane Hugo in September 1989. The city persevered and the work continued, however, and Charleston’s Waterfront Park formally opened in May of 1990. One of the park’s most popular features is the ring of jets that provide a canopy of cool, refreshing water to thousands of sun-baked tourists every year. I don’t know if the designers of this fountain were inspired by the old awnings that once shaded customers along the fringes of Vendue Range in the 1800s, but it seems a fitting allusion to me.

NEXT: Carolina Day: A Primer for Newcomers

PREVIOUSLY: A Brief History of Marion Square, Part 2

See more from Charleston Time Machine