The Unmarked Grave of Ellen O’Donovan Rossa

Processing Request

Processing Request

The death of Ellen O’Donovan Rossa, a poor Irish widow, in Charleston in September 1870 might have gone unnoticed by the world, but for the international notoriety of her distant, incarcerated son, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa. His reputation as an ardent nationalist inspired local Irishmen to memorialize Rossa’s mother as an expression of respect and solidarity. Their efforts were thwarted by the hands of time, however, as Ellen’s grave remains unmarked today.

Today’s program concerns the story of an obscure local mother and her famous son. This being Women’s History Month, as well as the annual feast day of St. Patrick, my intention is to highlight the memory of this forgotten Irish mother whose mortal remains rest in Charleston. Most of the few facts known of her life come to us through the writings of her famous son, however, and so, to understand the context of her life and memory, we are obliged to follow a bit of his life story as well. In fact, the reasons behind Ellen O’Donovan Rossa’s move to Charleston in 1870, as well as the local efforts to commemorate her passing a few months later, are firmly rooted in the the international career of the son she called “Jerrie.” His 1915 funeral in Dublin triggered a wave of nationalist expression in Ireland that sparked the Easter Rising of 1916, which ultimately led to the creation of the independent Republic of Ireland. Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa is an important figure in the history of modern Ireland, but his poor Irish mother languishes within an unmarked grave in Charleston.

Ellen Driscoll or O’Driscoll was born in the southwest of County Cork, in the southwest of Ireland, either in 1798 or in 1803, to Cornelius Driscoll and Anna Ní Laoghaire. The reports of Ellen’s death in 1870 describe her as being in the seventy-third year of her life, meaning that she had celebrated seventy-two anniversaries of her birth in 1798. In his published memoirs, however, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa said his mother was married at age fifteen, and he came along thirteen years later, in 1831. That arithmetic would place her birth in 1803 and, I believe, should be taken with a grain of salt.[1] Regardless of the precise date of her birth or wedding, Ellen, or “Nellie,” as she was known, married sometime before 1820 one Denis Donovan, or O’Donovan, who was also born in the southwest of County Cork around 1790.

Denis Donovan and Ellen Driscoll were poor, Irish-speaking tenant farmers in the early nineteenth century, but both were descended from families that had once enjoyed great prominence in the region, before successive waves of English persecution over several centuries decimated the traditional political and economic structure of Ireland. Having seized control of most of the island by force, English colonial officials generally ignored or suppressed the traditional Irish language (Gaeilge) and rendered family names and place names with Anglicized versions. The surnames Driscoll and Donovan, for example, are Anglicized renderings of the Irish names Ó hEidirsceoil and Ó Donnabháin, respectively. The suffix “Rossa,” which Jeremiah O’Donovan adopted in the 1850s, represents a nickname that his family had traditionally used to identify the branch of the O’Donovan family that originated around the townlands of Rossmore.[2]

Jeremiah Donovan was born in 1831 at the family’s home in Reanascreena (Rae na Scrine), near Ross Carbery (Ros Ó gCairbre), in the west of County Cork (Contae Chorcaí). His paternal uncle, Cornelius Donovan, was among the first of the family to leave the area in 1841, when he moved his family to Philadelphia. The remaining relatives suffered mightily during the Great Famine that commenced in 1845, and they joined the ranks of millions of Irish people who were uprooted and scattered by that four-year crisis. Jeremiah’s father, Denis Donovan, died in 1847, and the family was evicted from its rural cottage. Now destitute, Ellen Donovan had no choice but to separate her children and find shelter with various relatives. At the age of sixteen or seventeen, Jeremiah went to live with the family of a paternal aunt near the town of Skibbereen (An Sciobairín), while his mother stayed in Ross Carbery. Jerrie’s younger brother, Con, went to live with a maternal branch in Reanascreena, while his older brother, John, embarked for Philadelphia to join his uncle.[3]

Jeremiah Donovan was born in 1831 at the family’s home in Reanascreena (Rae na Scrine), near Ross Carbery (Ros Ó gCairbre), in the west of County Cork (Contae Chorcaí). His paternal uncle, Cornelius Donovan, was among the first of the family to leave the area in 1841, when he moved his family to Philadelphia. The remaining relatives suffered mightily during the Great Famine that commenced in 1845, and they joined the ranks of millions of Irish people who were uprooted and scattered by that four-year crisis. Jeremiah’s father, Denis Donovan, died in 1847, and the family was evicted from its rural cottage. Now destitute, Ellen Donovan had no choice but to separate her children and find shelter with various relatives. At the age of sixteen or seventeen, Jeremiah went to live with the family of a paternal aunt near the town of Skibbereen (An Sciobairín), while his mother stayed in Ross Carbery. Jerrie’s younger brother, Con, went to live with a maternal branch in Reanascreena, while his older brother, John, embarked for Philadelphia to join his uncle.[3]

At the same moment that Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa’s family was obliged to separate, a feeling of intense frustration gripped many of the young people in Ireland. They resented Britain’s discriminatory and misanthropic administration of Ireland, and their anger boiled over into acts of armed resistance in the summer of 1848. This brief and limited nationalist uprising, known as the Young Ireland Rebellion, was immediately crushed by the British government, but its revolutionary spirit lingered on for many years. Some of the surviving participants were arrested, tried, and exiled. Others fled to France, Australia, and to the United States, where they settled in places like New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Charleston.

Sometime in the early 1850s, John Donovan in Philadelphia sent passage money for his mother, Ellen, and sister, Mary (born in 1837) to migrate to the United States. Jeremiah walked with his family as far as Reanascreena Cross, then said goodbye to his mother and sister in the middle of the road before they continued on toward the ship waiting at “the Cove of Cork” (formerly Queenstown, now Cobh). “The cry of the weeping and wailing of that day rings in my ears still,” he wrote in 1898. “I stood at that Renascreena [sic] Cross till this cry of the emigrant party went beyond my hearing. Then, I kept walking backward toward Skibbareeen, looking at them till they sank from my view over Mauleyregan hill.”[4]

Now a young adult living among distant relatives, Jeremiah was searching for direction and purpose in his native land. Having survived the chaotic famine that killed nearly one million people, and having witnessed a failed uprising that scattered so many promising young men, he was outraged by the callous colonial policies and practices that Britain had used to enfeeble the Irish people in their own land. While working as a shopkeeper in Skibbereen in 1856, Jeremiah founded the Phoenix National and Literary Society, a grassroots organization with a mission to “liberate Ireland by force of arms.”

Two years later, in 1858, the Phoenix Society merged with a new, Dublin-based organization called the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Their collective mission was to build support for Ireland’s independence from British rule, and to create a sovereign Irish republic governed by and for the Irish people. While some Irish nationalists favored reaching this goal through a slow parliamentary process, the IRB represented the continuation of the martial spirit of the Young Irelanders. In brief, O’Donovan Rossa, as he now called himself, and the Irish Republican Brotherhood sought to use force to subvert the British hegemony and to assert Ireland’s right to self-determination. Shortly after the formation of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the British government arrested O’Donovan Rossa and other members of the IRB. They were held without charge or trial from December 1858 until July 1859.[5]

Meanwhile in the United States, a number of the young nationalists who fled Ireland in the wake of the failed uprising in 1848 continued to harbor animosity towards British rule in their homeland. In New York, John O’Mahony and a number of his exiled countrymen formed a new organization called the Fenian Brotherhood, named after the Fianna, the warriors of Irish mythology led by the legendary Finn MacCool (Fionn mac Cumhaill). The American Fenians were mostly found in the Northern states, and had a strong presence in the Union Army during our Civil War (1861–65), but there were pockets of Fenian support in the South. It appears that Britain’s tacit support of the Confederacy (because of the cotton trade) and the Fenian support of the then-liberal Republican Party conspired to keep Southern Fenians (mostly conservative Democrats) underground during the early 1860s.

During the American Civil War, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa made a brief trip to the United States. He spent most of the summer of 1863 in New York, where he witnessed the infamous Draft Riots that rocked the city and claimed more than a hundred lives. Much of his visit was occupied by meetings with the senior officers of the Fenian Brotherhood, but he also made time for a week-long family reunion in Philadelphia. Arriving at his brother’s house at ten in the evening, Jeremiah faced the mother he had last seen when they parted in the middle of the road at Reanascreena Cross more than a decade earlier. In his later memoirs, Rossa recalled that she did not recognize him. Her eyesight must have been failing. She was told it was Jerrie. “No, no, ‘tis not Jerrie,” said Ellen, and then reached forward with both hands to feel his forehead. There she sought and found a scar from a childhood injury. Mother and son embraced gleefully, “and then came the kissing and the crying with the memories of the ruined home and the graves we left in Ireland.”[6]

The years of exile and poverty were not kind to Ellen O’Donovan Rossa. Jeremiah described his mother as once being “a tall, straight, handsome woman, when I was a child, looking stately in the long, hooded cloak she used to wear.” When they were reunited in Philadelphia in July of 1863, he found “a prematurely old, old woman . . . with a yankee shawl and bonnet, looking as old as my grandmother. [S]he was nothing more than a sorry caricature of the tall, straight, handsome woman with the hooded cloak, that was photographed—and is photographed still—in my mind as my mother.”[7] After a brief, week-long visit, mother and son parted once more, never to see each other again.

Back in the Emerald Isle, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and the Irish Republican Brotherhood continued their efforts to rouse support for Irish independence by publishing a nationalist Irish newspaper. For such acts, Rossa and several of his republican cohorts were again arrested in 1865 and charged with treason against Britain. They were tried and convicted in England and given a life sentence at hard labor. All of the abovementioned information was broadcast around the English-speaking world in the 1850s and 1860s, and the people of Charleston read all about the Fenian movement in our local newspapers.[8] While local Anglophiles undoubtedly sneered at such rabble-rousing activities, a number of the Irish and Irish-American people of Charleston felt great sympathy for their republican brothers back in Ireland.

Back in the Emerald Isle, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and the Irish Republican Brotherhood continued their efforts to rouse support for Irish independence by publishing a nationalist Irish newspaper. For such acts, Rossa and several of his republican cohorts were again arrested in 1865 and charged with treason against Britain. They were tried and convicted in England and given a life sentence at hard labor. All of the abovementioned information was broadcast around the English-speaking world in the 1850s and 1860s, and the people of Charleston read all about the Fenian movement in our local newspapers.[8] While local Anglophiles undoubtedly sneered at such rabble-rousing activities, a number of the Irish and Irish-American people of Charleston felt great sympathy for their republican brothers back in Ireland.

A “circle” of the Fenian Brotherhood existed in Charleston by April of 1865, but the makeup of its early membership is unknown. When the group published a tribute of respect for recently-assassinated President Abraham Lincoln, the Protestant preachers of Charleston denounced the Fenians from the pulpit. An anonymous member then published a defense of the brotherhood, stating that it was not interested in either religious denominations or political parties. “The Fenian Brotherhood,” said the correspondent, “are a fraternity numbering nearly two millions [sic] of brave men, who are composed of both Protestants and Catholics, and whose sympathies are with the enslaved people of Ireland, and who now intend, at some future day, to loose from Ireland’s fettered limbs the chains which bind her down, and restore to her people their life and their liberty.”[9]

The Charleston branch of the Fenian Brotherhood named itself the “Robert Emmet Circle,” in honor of the Irish nationalist patriot executed by the British for his involvement in the failed United Irishmen Rebellion of 1798. During the mid- to late 1860s, they held regular meetings at the Palmetto [Fire] Engine House, located at what is now No. 27 Anson Street. By the beginning of 1866, the “centre” of the local Fenian “circle” was identified as James Power (1815–1879), a teetotaling boatbuilder who had emigrated from County Kilkenny to Charleston in the wake of the failed Young Ireland movement of 1848.[10] There was even a circle of the Fenian Sisterhood in Charleston, and both the Sister- and Brotherhood held fancy dress balls at Hibernian Hall on several separate occasions in the post-Civil War era.[11]

In the autumn of 1868, nearly three years into Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa’s life sentence, his wife came to the United States to raise support for the incarcerated members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Mary Jane “Molly” Irwin O’Donovan-Rossa (1846–1916), described as “a young Irish beauty” possessed of “a remarkable voice,” was the third wife of the celebrated Fenian. For more than six months she traveled across North America giving numerous recitations of poetry, song, and nationalist rhetoric “for the purpose of obtaining means and influence to procure her husband’s release, or at least a mitigation of his sentence.” Mrs. O’Donovan Rossa, as she was called, came from Savannah to Charleston on April 28th, 1869, and checked into the old Charleston Hotel on Meeting Street. The following evening, she gave a “spirit-stirring” performance before a large crowd at Hibernian Hall. The Charleston Daily News described the evening as “a rare literary treat,” and added that the object of Mrs. O’Donovan Rossa’s tour was “one of the holiest that ever engaged the soul of a true woman. We most heartily wish her God-speed in her efforts.”[12]

The name O’Donovan Rossa again returned to the pages of the Charleston news at the end of 1869 when the people of County Tipperary elected the still-incarcerated “traitor” to represent them in the British Parliament. Prime Minister William Gladstone succeeded in disqualifying his election in early 1870, but the incident provided the Fenian movement and the Irish Republican Brotherhood with a copious amount of sympathetic press.[13] By sitting in an English prison and loudly protesting his incarceration, O’Donovan Rossa, as he was generally called now, proved to be a powerful lightning rod for Irish nationalist sentiment, both at home and abroad. A Charleston newspaper even reprinted one of his prison letters, in which the “Irish patriot” described himself as a “political convict” unjustly held by an oppressive foreign power.[14]

Besides this local media coverage, and besides Mrs. O’Donovan Rossa brief visit here in the spring of 1869, I haven’t been able to find any evidence of a link between Charleston and the family of the famous Fenian. It is possible that some Irish members of the local Fenian Brotherhood were in contact with the O’Donovan clan in Philadelphia, but the details of such a connection are quite obscure today. Nevertheless, some correspondence or conversation must have taken place in the latter part of 1869, because Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa’s mother (Ellen), sister (Mary), and brother-in-law (Walter Webb) moved to Charleston at the beginning of 1870. We know something about the timing of this move because of a brief and highly unusual notice that appeared in the Charleston Daily News on the first day of January, 1870: “A Mr. Webb, brother-in-law of O’Donnovan [sic] Rossa, has been appointed a member of the city police.”[15]

The details surrounding the Webb family’s removal from Philadelphia to Charleston are a mystery. Walter Webb was a native of Ireland who served in the 13th Regiment of Pennsylvania Cavalry during the Civil War. It’s unclear when he emigrated or when he married Mary O’Donovan Rossa, but we know that Webb was employed as a policeman in Philadelphia between 1867 and 1869.[16] I think it’s unlikely that such a man would abandon a good job in a major city and move to a strange place without some good reason. Perhaps he ran afoul of the Philadelphia Fenians and sought a change of scenery. It’s also possible that some members Charleston Fenian circle learned of his connection to the sister and mother of the famous O’Donovan Rossa and invited them to pursue a new life in Charleston. Perhaps another Irishman policeman from the City of Brotherly Love moved to the Palmetto City and recommended Webb do the same.

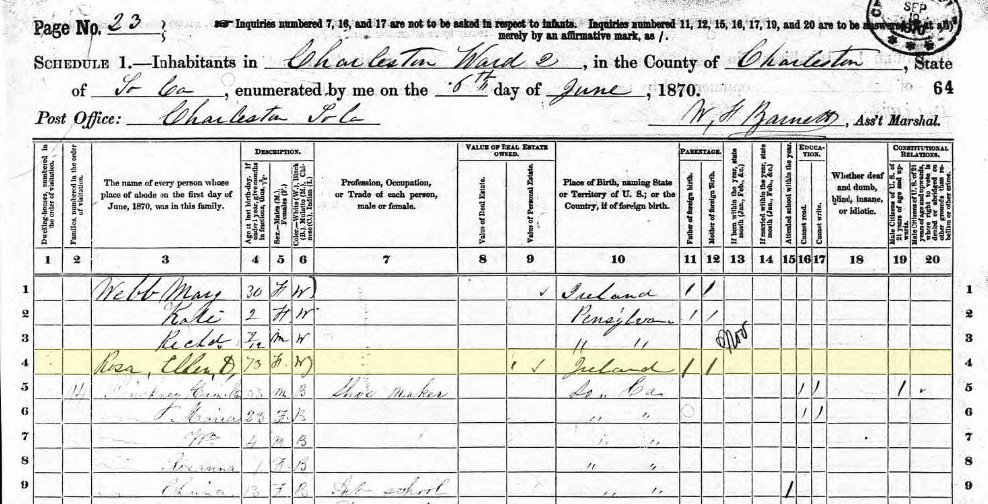

Whatever the reason behind their move, Walter Webb and his family settled in Charleston at the beginning of 1870. On the 6th day of June, a Federal census enumerator visited their household in Ward No. 2, where they were renting rooms in a two-and-a-half story brick single house at No. 32 King Street (now called No. 38 King Street), at the northeast corner of Whim Court (now called Weims Court). The household included 35-year-old Irish policeman Walter Webb, his 30-year-old Irish wife, Mary, and their two children who were born in Pennsylvania: Kate [Catherine], aged two, and Richard, born seven months earlier in November 1869. One next-door-neighbor was another Irish-born policeman named Francis Riley, while on the other side was Hamilton Pinckney, a young “black” shoemaker born in South Carolina.[17]

Whatever the reason behind their move, Walter Webb and his family settled in Charleston at the beginning of 1870. On the 6th day of June, a Federal census enumerator visited their household in Ward No. 2, where they were renting rooms in a two-and-a-half story brick single house at No. 32 King Street (now called No. 38 King Street), at the northeast corner of Whim Court (now called Weims Court). The household included 35-year-old Irish policeman Walter Webb, his 30-year-old Irish wife, Mary, and their two children who were born in Pennsylvania: Kate [Catherine], aged two, and Richard, born seven months earlier in November 1869. One next-door-neighbor was another Irish-born policeman named Francis Riley, while on the other side was Hamilton Pinckney, a young “black” shoemaker born in South Carolina.[17]

Also present in the Webb family household in the 1870 census was, of course, “Ellen D. Rosa” [sic], age 73, a native of Ireland. The printed census form included a column asking whether or not the subject was “deaf and dumb, blind, insane, or idiotic,” but the census enumerator did not make any sort of mark in this column for Ellen. Her son Jerrie remembered that she had difficulty recognizing him in Philadelphia in 1863, but we can’t know for certain whether her eyesight was failing, or whether that earlier reunion simply took place in a darkened room.

Shortly after Walter Webb moved his family to Charleston in early 1870, the city’s Irish community learned of their connection to the famous Fenian. On April 18th, a number of gentlemen published “a call for a mass meeting of the Irish citizens and the friends of Irishmen, at the Hibernian Hall to-morrow night, when a testimonial will be gotten up for the mother of O’Donovan Rossa, who is at present in the city.”[18] Accordingly, “quite a number of our Irish citizens” came to the meeting, but “the unfavorable aspect of the weather” discouraged a large turnout. The meeting commenced at half-past 8 o’clock, and the assembled men chose James M. Mulvaney to act as chairman.

“The chairman explained that the meeting was called for the purpose of adopting measures for the relief of the mother of O’Donovan Rossa, who is now in the city in a destitute condition.

Captain James Armstrong, Mr. M. P. O’Connor, Mr. L. C. Northrop and the chairman made brief and eloquent speeches, referring to the suffering of the captive immured in a British prison because he had dared to lift up his voice in behalf of his oppressed and down-trodden land, and impressing upon the audience that, as by this imprisonment his mother was deprived of the support which her son had so gratefully and cheerfully given her, it was the duty of Irishmen, everywhere, to see that she was cared for. Captain Armstrong stated that when he recollected that, in 1848, in this hall, the Irishmen of this city had contributed $22,000 to aid the cause of Ireland, he doubted not that this appeal to them would meet with a hearty and liberal response.

At the conclusion of the speeches, all of which were very brief, Captain Armstrong introduced the following preamble and resolutions, and moved that a committee be appointed to carry out the resolutions:

Whereas, The Irish citizens of Charleston are, and have always been, devoted to the great spirit of Irish liberty, and are always ready to approve the sterling character of their race; and whereas, Irishmen all over the world are united in their admiration of the heroism and patriotism of Ireland’s O’Donovan Rossa, the unflinching representative of the martyrdom of Ireland under English rule; and whereas, this distinguished patriot has suffered for years the death of a living tomb, in the dungeons of Portland, in vindication of the right of his country to be free; and whereas, the faithful Irish arm upon which his aged mother leans for support, is helpless to serve her in this hour of her necessity; therefore, be it

Resolved, That we, the Irishmen and friends of Ireland, in mass meeting assembled, have heard the emotions of patriotic ardor and satisfaction of the arrival of the venerable mother of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa in this city.

Resolved, That we extend her a true Irish welcome and honor in her presence the fidelity and character of her noble son.

Resolved, That we present her with a fitting testimonial of our respect and regard, and that we call upon the Irish citizens and the friends of Ireland in this city to contribute to the object of this meeting.”

At the end of this parliamentary action, the chairman appointed a committee to carryout the resolutions of the informal association of Irish sympathizers, “who were instructed to report within a month the result of their efforts.”[19] I have found no subsequent report of the committee’s activities published in the newspaper, but it appears that the elderly Mrs. O’Donovan Rossa was welcomed, admired, and looked after in some way during her final days in Charleston. This “estimable lady” was “in feeble health” during the hot and sultry summer of 1870, however, and died on the first day of September. According to the City of Charleston's weekly "Return of Deaths" (now held at CCPL), she succumbed to an "enteric fever," most likely typhoid. The following day, the Charleston Daily News published a brief but eloquent notice that merits a full reading:

“Death of Mrs. O’Donovan Rossa. This aged and respected lady, who is the mother of the distinguished Irish martyr now wearing out an inglorious existence in a British prison, when his valor and eloquence might be illustrated in the cause of his country, took place yesterday afternoon, at five o’clock, at the residence of her son-in-law, Walter Webb, Esq., No. 32 King-Street, where she received every kindness that limited means would permit. She will be buried from the same place this afternoon, at four o’clock. She has been ill for some time, while her friends were buoyed up with the idea that she would live long enough to see the fruition of her intrepid son’s hopes, the liberty of Ireland; but she has gone to the grave ere the great deed is consummated. It may not be out of place to say that the gallant spirit that survives her [that is, her son], has defiantly refused to testify to a commission recently appointed by Parliament to investigate matters pertaining to his case. There will no doubt be a large attendance at the obsequies of all who reverence her memory, and him whom she held so proudly dear.”[20]

The funeral of Ellen Driscoll O’Donovan Rossa on September 2nd, 1870, was conducted by the Rev. Father Francis Shadler at “the Cathedral Chapel” on Broad Street, since the Catholic Cathedral of St. John and St. Finbar had burned to the ground in the great fire of 1861. Later that day, her remains were interred at St. Lawrence Cemetery on Charleston Neck.[21] The family apparently had sufficient means to purchase a burial plot, but there was no money for a headstone. One month later, however, a group of local Irishmen formed the “O’Donovan Rossa Monument Association,” with the goal of erecting “a suitable monument over the remains of the mother of Rossa, the Irish martyr.”[22] A few weeks later, on the 26th of October, the association published a formal appeal for donations:

“The mother of the Irish patriot, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, died in this city last September, and her remains lie interred in St. Laurence [sic] Cemetery, far away from the clay that enwraps the dust of her Cineál Sinnseor [own people] in the old Reilig [cemetery], where, if she had her choice, she would fill a grave, and the Bean Chaoine [keening women] would tell the deeds of the O’Driscols, in days long by. As yet, there is no stone to mark the last resting-place of the Spartan mother, but, being well aware of the devotion and patriotism of our race, we send forth an appeal to our country-men for assistance to aid in the erection of a suitable monument to her memory. We do not intend to have a costly monument erected, but a plain and appropriate one, which will reflect credit upon all who love and applaud the deeds of her noble son. . . . Let every true son of Erin come up like a man, and send down the name of their martyred patriot to posterity in monumental marble.”[23]

Thanks to the magic of the Internet and its world of digital resources, one can take a sort of virtual tour of St. Lawrence Cemetery through the popular website Findagrave.com. I recently searched that website and found no mention of Ellen Driscoll O’Donovan Rossa, or any permutation of those Irish names. I’ve also walked and bicycled through St. Lawrence Cemetery on many occasions in the past, and I’ve never found a headstone or marker of any kind for the mother of the famous Irish patriot. Faced with these facts, we have to wonder if the O’Donovan Rossa Monument Association succeeded in their fund-raising appeal. As their prospectus stated, they intended to erect a “plain,” “marble” monument, the expense of which could not have been great. There seemed to ample support for such a cause in the autumn of 1870, but evidence of their success is now lacking. Perhaps a plain marble headstone was purchased and placed above her grave at that time, but some intervening event removed or obscured it. Perhaps a misguided admirer stole it as a souvenir. Perhaps the marker was so small that it became obscured by weeds or dirt when it toppled over during a hurricane. Whatever the cause, Ellen O’Donnovan Rossa’s grave is current unmarked, and the knowledge of its location appears to have been lost as well. The extant business records of the cemetery confirm her burial on the 2nd of September, 1870, but do not describe the location of her grave. [24]

Thanks to the magic of the Internet and its world of digital resources, one can take a sort of virtual tour of St. Lawrence Cemetery through the popular website Findagrave.com. I recently searched that website and found no mention of Ellen Driscoll O’Donovan Rossa, or any permutation of those Irish names. I’ve also walked and bicycled through St. Lawrence Cemetery on many occasions in the past, and I’ve never found a headstone or marker of any kind for the mother of the famous Irish patriot. Faced with these facts, we have to wonder if the O’Donovan Rossa Monument Association succeeded in their fund-raising appeal. As their prospectus stated, they intended to erect a “plain,” “marble” monument, the expense of which could not have been great. There seemed to ample support for such a cause in the autumn of 1870, but evidence of their success is now lacking. Perhaps a plain marble headstone was purchased and placed above her grave at that time, but some intervening event removed or obscured it. Perhaps a misguided admirer stole it as a souvenir. Perhaps the marker was so small that it became obscured by weeds or dirt when it toppled over during a hurricane. Whatever the cause, Ellen O’Donnovan Rossa’s grave is current unmarked, and the knowledge of its location appears to have been lost as well. The extant business records of the cemetery confirm her burial on the 2nd of September, 1870, but do not describe the location of her grave. [24]

After many months of political negotiations abroad, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa was released from prison near the end of 1870, shortly after his mother’s death. He and a small group of Irish Republican comrades immediately sailed for New York in compliance with their exile from the British realm. In late January 1871, the United States Congress formally resolved to extend to Rossa and his colleagues “a cordial welcome to the capital and to the country.” I’ve found no evidence that Jeremiah came to Charleston after he settled in New York, but he would certainly have received word of his mother’s death and burial here. We might imagine that his filial grief was lessened somewhat by the knowledge that his Fenian brothers in the Palmetto City had attended to his mother’s needs during her final days here.[25]

In his Recollections, published in 1898, O’Donovan Rossa fondly remembered his departed mother. During the Famine, when his father perished and the English landlord evicted the poor family, Rossa remembered his teenage self regaling his mother with boastful plans “of the things I’d do for Ireland when I grew up to be a man.” “God help your poor foolish head!” she would say to him, but those foolish ideas stayed with him into adulthood.[26] Even after being exiled to New York, O’Donovan Rossa organized American support for Irish republican activity, and instigated a controversial bombing campaign that earned him the nickname O’Dynamite Rossa. When he died in New York, his body was immediately shipped back to Ireland. His funeral on the 1st of August, 1915, drew tens—perhaps hundreds—of thousands of people into the streets of Dublin who wished to acknowledge the passion and perseverance of their exiled brother. The graveside oration given by Pádraig Pearse on that day roused Irish republican spirits to a fever pitch and served as a call to action.[27] Seven months later, Pearse and other members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood launched a small military offensive against the British government in Dublin. The failed Easter Rising of 1916 did not achieve its goal of establishing an independent Irish republic, but it did set in motion a long and painful chain of events that led to the creation of the Irish Free State and, eventually, the present Republic of Ireland.

On a number of occasions and in many different ways, the people of Charleston regularly acknowledge our community’s rich Irish heritage and celebrate the men and women who helped build a new home far from that ancestral island. Today we remember Ellen Driscoll O’Donovan Rossa, the “tall, straight, handsome” Irish woman who brought her son, Jerrie, into the world in 1831, and who drew her last breath here in Charleston in 1870. She did not live to see the culmination of her son’s life work, but Irish men and women around the world remember her gift to their homeland. Although her grave is not marked, her memory is yet alive.

[1] Charleston Daily News, 3 September 1870: “Mrs. O’Donnovan [sic] Rossa was born at Rossmore, County of Cork, Ireland, in 1798.” Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, Rossa’s Recollections, 1838 to 1898 (Mariner’s Harbor, N.Y.: by the author, 1898), 12. You can read this text on the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/rossasrecollecti00odon/page/n7.

[2] O’Donovan Rossa, Recollections, 82–83.

[3] O’Donovan Rossa, Recollections, 51, 119, 141–42, 151–53.

[4] O’Donovan Rossa, Recollections, 142. Mary Donovan was baptized in 1837. See http://skibgene.blogspot.com/2010/12/roots-of-jeremiah-odonovan-rossa.html.

[5] The recent book by Shane Kenna, Jeremiah O’Donovan Ross: Unrepentant Fenian (Sallins: Merrion, 2015), provides an excellent overview of his career.

[6] O’Donovan Rossa, Recollections, 142, 379–82.

[7] O’Donovan Rossa, Recollections, 59, 143.

[8] See, for example, the article “Excitement among the Fenians” in the Charleston Courier, 6 March 1866.

[9] See “Meeting of the Fenian Brotherhood” in Charleston Courier, 1 May 1865, and “Fenian Brothers” in Charleston Courier, 9 May 1865.

[10] The earliest mention of the Palmetto Engine House appears in a Fenian Brotherhood meeting notice in Charleston Courier, 25 August 1865. The earliest Fenian notice to mention the “centre” appears in Charleston Courier, 1 February 1866. Biographical details of James Power’s life can be found in his obituary in Charleston News and Courier, 10 May 1879. The name of the circle was first mentioned in a meeting notice in Charleston Daily News, 7 June 1866.

[11] The Brotherhood’s first “Grand Ball” was advertised in Charleston Courier, 18 November 1865; its “Third Annual Ball” was advertised in Charleston Daily News, 18 February 1870. The Fenian Sisterhood was announced in Charleston Daily News, 29 March 1866, and reviewed in Charleston Daily News, 7 April 1866.

[12] Charleston Daily News, 5 November 1868, page 1: “The New York Sorosis.” For her Charleston performance, see the advertisement in Charleston Daily News, 24 April 1869, the pre-show puff in Charleston Daily News, 28 April 1869. A notice of her hotel arrival and a review of her performance appear in Charleston Daily News, 29 April 1869.

[13] News of Rossa’s election appeared on the front page of the Charleston Daily News on 29 November 1869, 17 January 1870, and 18 January 1870.

[14] Charleston Daily News, 31 March 1870, page 4.

[15] Charleston Daily News, 1 January 1870, page 3, “Crumbs.”

[16] See Isaac Costa, comp., Gospill’s Philadelphia City and Business Directory for 1867-8 (Philadelphia, James Gospill, 1868), 1305; Isaac Costa, comp., Gospill’s Philadelphia City and Business Directory for 1868-9 (Philadelphia, James Gospill, 1868), 1600. O’Donovan Rossa, Recollections, 144, states that his brother-in-law, Walter Webb, served in the 69th Pennsylvania Cavalry, but he was mistaken. Rossa’s brother, John, served in the 69th Pennsylvania Infantry.

[17] Another Irishman named Walter Webb (ca. 1801–1890) lived at No. 40 King Street in 1870. He had emigrated in 1845 and worked as a gardener and florist, and had a Charleston-born son named Walter Webb (1846–1886). I have not found evidence of any link between these two families. Neither of the men in the older Webb family of Charleston appear to have participated in the Fenian activity of the 1860s and 1870s.

[18] Charleston Daily News, 18 April 1870. The gentlemen responsible for organizing the meeting included “A. G. Magrath, William Moran, James Conner, J. M. Mulvaney, Edward McCrady, Jr., J. J. Grace, J. F. O’Neill, Philip Fogarty, James Power, John Kenney, W. E. Mikell, M. P. O’Connor, John Burke, P. Brady, L. C. Northrop and others.”

[19] Charleston Daily News, 20 April 1870, “Meeting of Irish Citizens.” The committee consisted of Messrs. Wm. Moran, John O’Mara, J. F. O’Neill, M. P. O’Connor, James Cosgrove, L. C. Northrop, James Powers, D. H. Gilliland, James Armstrong, and John D. Kennedy.

[20] Charleston Daily Courier, 2 September 1870, page 2. A brief death notice also appears in Charleston Daily News, 2 September 1870, page 3.

[21] The funeral location and officiant are mentioned in Charleston Daily News, 3 September 1870, which mistakenly noted that she was buried at Magnolia Cemetery, which adjacent to St. Lawrence. Records held by the local diocesan office confirm her interment at St. Lawrence Cemetery. See Office of Cemeteries records, Diocese of Charleston Archives, Charleston, SC. My thanks to Brian Fahey, diocesan archivist, for his kind assistance in this matter.

[22] Charleston Daily News, 10 October 1870. The officers were M. E. Collins, chairman; James Powers, treasurer; and James Brennan, secretary.

[23] Charleston Daily Courier, 26 October 1870, page 2, “Mrs. O’Donovan Rossa’s Monument—An Appeal to Irishmen and Friends of Liberty. . . . All moneys for the purpose should be sent by draft or post office order, and made payable to Dr. M. H. Collins, of this city. Trusting the response will be prompt and generous to this appeal, we remain, fellow-countrymen, and friends of liberty, your obedient servants, James Power, Stephen Maloney, James Looby, M. H. Collins, James Brennan.” My thanks to Denis Bergin for his assistance with the Irish translations.

[24] Personal communication with Brian Fahey, archivist of the Catholic Diocese of Charleston. Walter and Mary Webb moved to Staten Island, New York, sometime before 1873. Mary Webb appears in that location in the 1880 federal census, with a seven-year-old child who was born in New York.

[25] Charleston Daily News, 31 January 1871, page 1: “Congressional Proceedings.” Rossa’s release and arrival in New York was also noted in Charleston Daily News, 24 January 1871, page 4, “The Exiles of Erin.” O’Donovan Rossa, Recollections, 6, acknowledges that he had “a mother buried in Carolina.”

[26] O’Donovan Rossa, Recollections, 58.

[27] You can see footage of O’Donovan Rossa’s funeral, which took place on August 1st, 1915, on YouTube. You can also see an hour-long RTÉ documentary about the 2105 Irish state commemoration of the centenary of O’Donovan Rossa’s funeral on YouTube.

PREVIOUS: Abraham the Unstoppable, Part 4

NEXT: Abraham the Unstoppable, Part 5

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments