Street Cars and Trolleys on Sullivan’s Island, 1875-1927

Processing Request

Processing Request

Once a remote and desolate beachfront, Sullivan’s Island has developed into a bustling and chic destination since the first summer residents camped there in 1791. That transformation could not have happened without the aid of ferries, mule-powered street cars, and electric trolleys that carried weary people from the mainland to the invigorating island surf over the past two centuries. Let’s roll back the wheels of time and explore the many moving parts of this important transportation story.

For much of the eighteenth century, Sullivan’s Island was and uninhabited barrier island that served as part of the quarantine protocol for the port of Charleston. Incoming ships suspected of carrying infectious diseases were required to anchor in the harbor and wait for a prescribed period of time, during which time they were allowed to land people on Sullivan’s Island. This protocol applied to white passengers and crews as well as to incoming ships carrying enslaved Africans. The state legislature suspended the legal importation of African captives into South Carolina in March 1787, but Sullivan’s Island continued to host a “lazaretto” for the quarantine of incoming white folks until 1796. Meanwhile, in early 1791, the state legislature granted permission for “such citizens of this state as may think it beneficial to their health to reside on Sullivan’s Island during the summer season have liberty to build on the said island a dwelling and out houses for their accommodations.”[1] During the summer of 1791, a number of wealthy local citizens rowed or sailed to the island in a variety of little boats and began constructing summer cottages on the seashore. Within a few years, the seasonal settlers formed a village at the southwestern end of the island called Moultrieville, which was incorporated in 1817. This was the beginning of the Sullivan’s Island we know today.

The first wave of people wishing to spend the summer months on the island had to contend with the simple but difficult question of how to get there, and how to transport the supplies and building materials needed to establish a summer residence. In the summer of 1791, one had to own a boat, or hire a boat and crew. Starting in the summer of 1792, however, veteran ferryman, James Hibben, began operating a daily ferry service that connected the peninsula of Charleston, the summer village of Mount Pleasant, and Sullivan’s Island. This seasonal ferry service, using row-boats and, later, horse boats, terminated at a landing in “the cove” on the northwest or “back side” of Sullivan’s Island (Between Stations 12 and 13). It continued for several decades until it was augmented, and eventually supplanted, by a steamboat ferry that commenced in the summer of 1820.[2] The advent of the steamboat ferry proved to be such a convenience to the seasonal residents of Sullivan’s Island that in 1828 the state legislature empowered the town council of Moultrieville to manage the ferry service to and from the island.[3] That municipal service was supplanted in 1852 by a new private venture, the Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island Ferry Company, which was re-chartered and reorganized after the Civil War, in 1870.[4]

Immediately after the end of the Civil War, private capitalists in the city of Charleston began constructing a street rail system on the peninsula. Urban street cars, rolling on steel rails imbedded in the streets, were all the rage in northern cities and in Europe in the 1860s. The technology represented a breakthrough in the concept of personal mobility, and it spawned the practice of what we now call “commuting.” The war had actually interrupted an 1861 plan to build a street rail network in the Palmetto City. After several years of delay, horse-drawn street cars began whisking Charlestonians across a network of rail lines in December of 1866. This new service captivated residents and visitors alike, and it was a major step forward in the history of transportation in the Lowcountry. We’ll talk more about this story in an upcoming episode.

In March of 1875, nearly a decade after the debut of Charleston’s urban street cars, a group of local investors chartered a new venture called the Middle Street Sullivan’s Island Railway Company. One month after its formal organization, in early April, the company hired a contractor (M. W. Conway) to lay two miles of track and empowered an agent in New Jersey to purchase a “dummy” engine (that is, a steam engine disguised to look like a passenger car). The company planned to open its new rail service by June 1st, and they came within a few days of meeting their goal. On June 15th, however, the local newspaper reported that “the dummy engine of the Middle Street Sullivan’s Island Railroad Company has proved to be a failure, and is now laid up for repairs. Mules will be substituted.” The substitution of animal power for steam power proved to be a permanent fix, and by the end of July the company had built stables for its mules at the “upper [or eastern] terminus” of the rail line.[5]

In March of 1875, nearly a decade after the debut of Charleston’s urban street cars, a group of local investors chartered a new venture called the Middle Street Sullivan’s Island Railway Company. One month after its formal organization, in early April, the company hired a contractor (M. W. Conway) to lay two miles of track and empowered an agent in New Jersey to purchase a “dummy” engine (that is, a steam engine disguised to look like a passenger car). The company planned to open its new rail service by June 1st, and they came within a few days of meeting their goal. On June 15th, however, the local newspaper reported that “the dummy engine of the Middle Street Sullivan’s Island Railroad Company has proved to be a failure, and is now laid up for repairs. Mules will be substituted.” The substitution of animal power for steam power proved to be a permanent fix, and by the end of July the company had built stables for its mules at the “upper [or eastern] terminus” of the rail line.[5]

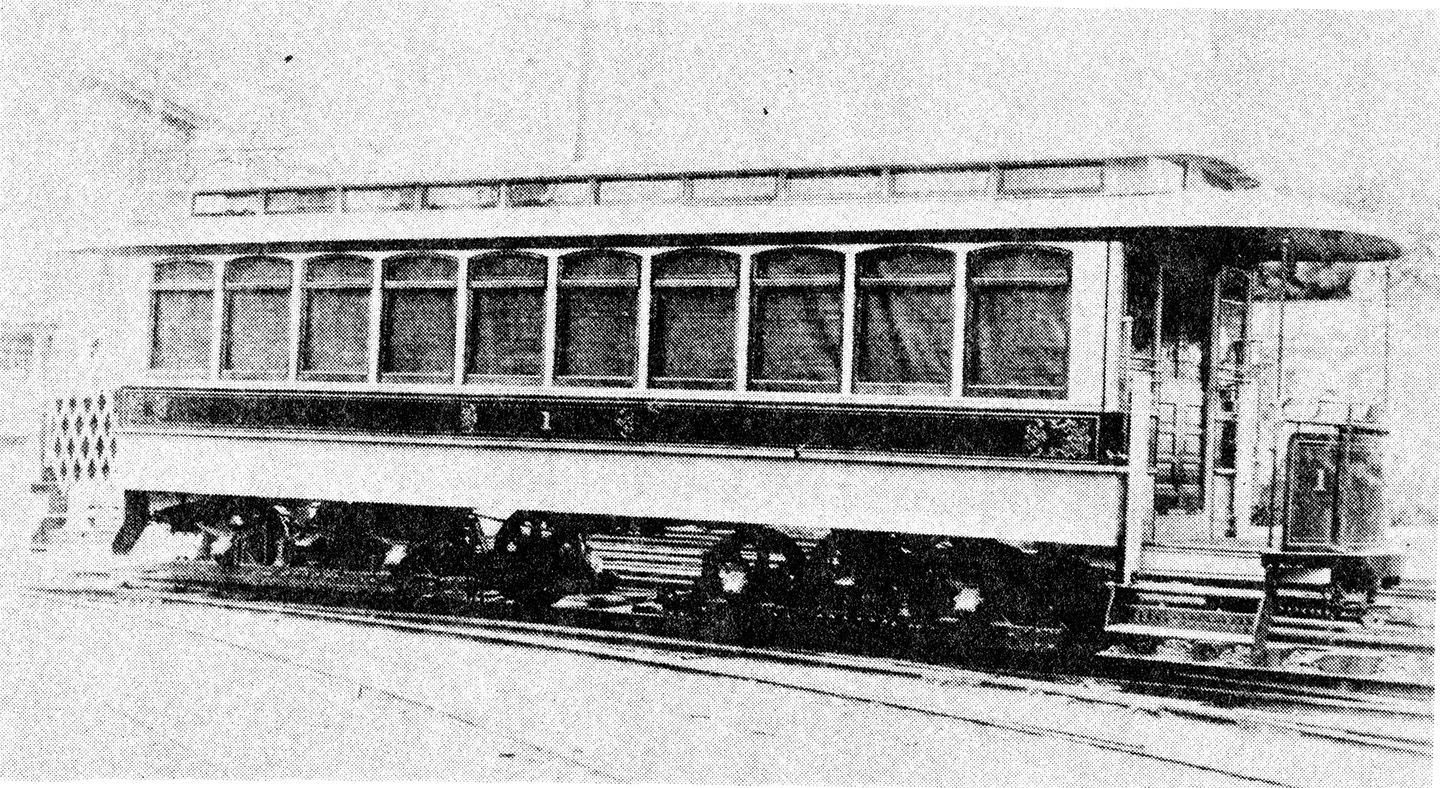

The Sullivan’s Island street car system was immediately popular, profitable, and practical. It simply enabled people to move up and down the length of the narrow island in a comfortable, shady, reasonably quick conveyance, without the need to bring a horse and buggy over from the mainland. The rail company’s rolling stock included six passenger cars (probably used in two groups of three) and twelve mules, who took turns working in pairs. Its track followed an axial route, commencing from the ferry landing at the cove and continuing northeastward along Middle Street for a total distance of two miles. I’m not sure if the track also extended to the west of the ferry landing, as I haven’t yet found a detailed map of the island from this era (1875 to about 1890), but I suspect it did. None of this might sound very grand, but keep in mind that the Middle Street railway was meant to serve just the people of Moultrieville, which at that time was pretty much confined to the western half of the island.

As the services provided by the ferry and street car companies lured an increasing number of seasonal tourists to the island, new facilities were needed to accommodate strangers who didn’t own a summer cottage and just wanted to stay for a few days to play on the front beach. Rather than building one or three modest hotels on the uninhabited eastern end of Sullivan’s Island, private investors leaped straight to luxury mode and opened a “first class” resort in the summer of 1884. Called the New Brighton Hotel, it was situated beyond the town of Moultrieville, near the center of the island, at the northeast end of the street rail line. (This site is now between Stations Nos. 22 and 23). The hotel was profitable at first, probably because of its novelty, but it soon entered a period of instability. After the massive hurricane of August 1885 and the destructive earthquake of September 1886 devastated the local economy, the New Brighton closed. In the ensuing years, it was repeatedly sold at auction to a chain of optimistic but ineffective owners. The economy eventually rebounded, however, and the vacant New Brighton Hotel reopened in the summer of 1895 as the slightly more modest Atlantic Beach Hotel.[6]

The optimistic economic outlook of the late 1890s convinced other investors to dream of even bigger plans. In 1897, the horse-drawn street rail system in peninsular Charleston was replaced by a new rail network using electric trolleys. At the same time, a South Carolina native living in Washington, D.C., Dr. Joseph S. Lawrence, came home to recruit investors in a scheme to run an electric trolley line across the length of Sullivan’s Island. Actually, Dr. Lawrence’s principal goal was to develop the isolated wilderness property adjacent to Sullivan’s Island, known then as Long Island, into a fashionable resort destination. In order to deliver construction materials, workers, and tourists to that location, he intended to create a trolley line that extended from the ferry landing in the village of Mount Pleasant, across the cove to the western tip of Moultrieville, through the length of Sullivan’s Island, across the ocean waters at Breach Inlet, and across the western third of Long Island. After purchasing Long Island and rebranding it with the more attractive name, “Isle of Palms,” Lawrence and his investors chartered the Charleston and Seashore Railroad Company in February of 1898.

In early March of 1898, the Moultrieville town council gave the “Seashore Company,” as it became known, permission to lay standard-gauge steel track and electrified trolley poles through their community. Work commenced almost immediately, in late March. By early June, most of the street track was in place and long lines of street poles were ready for the network of electrical wires. Rows of wooden piles had been sunk for the bridges across the cove to Mount Pleasant and across Breach Inlet to Long Island. Most of the wooden trestles used to construct the bridges were in place, but still lacked rails. A steel draw bridge across Breach Inlet was in place and ready for service. A brick structure to house the electrical power plant was built on the cove side of the island, adjacent to the landing of the trestle bridge. The long bridge across the marsh and cove linking Mount Pleasant to Moultrieville even included what was called “a convenient driveway” that ran “along side of the railroad track.” Describing this feature as “safe for carriages,” the local press noted that “the villagers are delighted to learn that they will be able to run over to the island” in their horse-drawn carriages.[7]

In early March of 1898, the Moultrieville town council gave the “Seashore Company,” as it became known, permission to lay standard-gauge steel track and electrified trolley poles through their community. Work commenced almost immediately, in late March. By early June, most of the street track was in place and long lines of street poles were ready for the network of electrical wires. Rows of wooden piles had been sunk for the bridges across the cove to Mount Pleasant and across Breach Inlet to Long Island. Most of the wooden trestles used to construct the bridges were in place, but still lacked rails. A steel draw bridge across Breach Inlet was in place and ready for service. A brick structure to house the electrical power plant was built on the cove side of the island, adjacent to the landing of the trestle bridge. The long bridge across the marsh and cove linking Mount Pleasant to Moultrieville even included what was called “a convenient driveway” that ran “along side of the railroad track.” Describing this feature as “safe for carriages,” the local press noted that “the villagers are delighted to learn that they will be able to run over to the island” in their horse-drawn carriages.[7]

While gangs of laborers were toiling long hours in the marsh and jungle at the cove and Long Island (Isle of Palms) in the spring of 1898, the region’s leading businessmen were holding intense negotiations in downtown Charleston. The plan advanced by Dr. Lawrence and his Seashore Company included a new ferry service to run from the east side of the peninsula, across the Cooper River, to a new wharf at Haddrell’s Point in the village of Mount Pleasant. At that point, the Seashore customers would simply walk a few steps from the ferry to the trolley, which would then whisk them through the village and over the water to the islands. This elaborate venture would compete directly with the existing Cooper River ferry service, operated by the old Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island Ferry Company, as well as the existing street car system on the island, operated by the Middle Street Railway Company. Dr. Lawrence and the Seashore Company wanted to buy out these competing firms, but the two older companies resisted. The new Seashore company, with its intermodal service, was going to charge a lower fare than its competition: it planned to charge 15¢ (one-way) to travel by ferry from Charleston to Mount Pleasant, and then by trolley to the Isle of Palms, or 25¢ for a round-trip. In response to this rate, the older ferry and street car companies immediately lowered their prices. Many locals and journalists wondered aloud, why would anyone want to ride the older ferries and the slow mule-cars when they could ride the faster, more modern ferries and the faster electric trolley across a longer, more convenient, and cheaper route?[8]

Despite its failure to absorb the competition in 1898, the Seashore Railroad Company persevered with its original plan. Although it had hoped to open the new trolley line by June 1st to capitalize on the summer tourist traffic, construction delays postponed the opening date into late July. On Sunday, July 24th, the track and equipment were finally ready for a trial. Anticipation was high as the islanders waited to see the trolley’s unofficial first run. As storm clouds gathered for a late afternoon summer squall, however, the people lost hope of witnessing a novelty. The soldiers garrisoned at Fort Moultrie had just sat down to their evening mess when “shouting in the distance and then the buzzing noise announced the advent of the trolley. Supper was neglected for once as the boys rushed to the front to give three cheers for luck.” The Charleston Evening Post noted that “when the trolley ran through the island on Sunday it received a perfect ovation, the like of which has never been tendered any visitor on the island. People rushed out in the rain and those who could not get to the track just climbed to the roof and other points of vantage to see the marvelous exhibition. Just think of a trolley running through the island, such an achievement has never come within the wildest dreams of the most enthusiastic dreamer on this island.” Shortly after this dramatic, rain-soaked exhibition, said the newspaper, the familiar old “‘mule-y-cars’ trotted along” their regular route through Moultrieville, “but not as merrily as of yore. They too received an ovation [from the assembled islanders,] which maybe they understood[,] for they blinked at the crowd and smiled sadly as they turned the angle on the way up the island.”[9]

The official debut of the Charleston and Seashore Railway Company’s new ferry and trolley service commenced at 3 p.m. on Thursday, July 28th, 1898. At that moment, a large crowd of dignitaries aboard the steam ferry Commodore Perry departed from the company’s new slip at Charleston’s Central Wharf (now the site of Fleet Landing restaurant) and crossed the Cooper River. After landing at the company’s new wharf at Haddrell’s Point, the crowd boarded trolley cars waiting at Station No. 1, adjacent to the ferry wharf in the village of Mount Pleasant. The electric cars rolled southeastward, past Stations No. 2 through 8, and crossed the trestle bridge to Sullivan’s Island. Landing at Station No. 9 at the western tip of the island, the trolley turned eastward and continued along Middle Street through Moultrieville. At the eastern end of the town, just past the Atlantic Beach Hotel, the track jogged one block to the north (through what is now Quarter Street), to Jasper Boulevard, and continued toward Station No. 32 at the eastern tip of the island. The new trestle draw bridge then carried the electric cars over Breach Inlet to the recently-renamed Isle of Palms. The rail line continued for nearly a mile and a half eastward through a newly-cleared path of dense wilderness and terminated at the Seashore Company’s new resort complex, around the site of modern 14th Avenue. (We’ll save further details about the Isle of Palms for a future episode).

According to a correspondent who took this eight-mile trolley route on opening day, the journey through Mount Pleasant and across the trestle bridge to to Sullivan’s Island took ten minutes, and the remaining distance to the end of the line on Isle of Palms “occupied about twenty-five minutes more.” That same correspondent noted that the operation of the trains was rather stiff, however, and expressed hope that the equipment and operators would soon settle into a smoother, faster routine. Another correspondent who rode the new trolley line in early August reported that “the trip from Charleston by the Commodore Perry to Mount Pleasant, and the trolley to the beach on the Isle of Palms, was made in just twenty-five minutes.” The true duration of this journey was probably somewhere between these two disparate experiences.[10]

Shortly after the opening of the Isle of Palms resort and the new ferry and trolley service, the president of the Seashore Railroad Company, Dr. Joseph S. Lawrence, died suddenly at the age of 51. He lived long enough to see the fruition of his island development scheme, and his ambitious spirit kept rolling along without him. Having completed the infrastructure and successfully launched the Charleston and Seashore Railroad Company, his business associates turned their attention to reducing their competition and expanding their profits. In February of 1899, the Seashore Company merged with the Charleston Street Railway Company, as well as the Charleston Gas Light Company and the Charleston Light and [Electric] Power Company to form the Consolidated Railway, Gas, and Electric Company. Two months later, in April 1899, the massive new “Consolidated” company bought out its remaining competition east of the Cooper River, namely the Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island Ferry Company and the Middle Street Sullivan’s Island Railway Company.[11] For the next fourteen years, the “Consolidated” exercised a monopoly over ferry and trolley transportation on both sides of the Cooper River.

Shortly after the opening of the Isle of Palms resort and the new ferry and trolley service, the president of the Seashore Railroad Company, Dr. Joseph S. Lawrence, died suddenly at the age of 51. He lived long enough to see the fruition of his island development scheme, and his ambitious spirit kept rolling along without him. Having completed the infrastructure and successfully launched the Charleston and Seashore Railroad Company, his business associates turned their attention to reducing their competition and expanding their profits. In February of 1899, the Seashore Company merged with the Charleston Street Railway Company, as well as the Charleston Gas Light Company and the Charleston Light and [Electric] Power Company to form the Consolidated Railway, Gas, and Electric Company. Two months later, in April 1899, the massive new “Consolidated” company bought out its remaining competition east of the Cooper River, namely the Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island Ferry Company and the Middle Street Sullivan’s Island Railway Company.[11] For the next fourteen years, the “Consolidated” exercised a monopoly over ferry and trolley transportation on both sides of the Cooper River.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the trolley service connecting Mount Pleasant, Sullivan’s Island, and the Isle of Palms continued to roll along in style. Customers were happy, the Consolidated company was profitable, and the three seasonal villages slowly began evolving into more stable, year-round communities. The reliable ferry service connecting them to peninsular Charleston allowed men to commute from the islands to a job in the city. Women living in the countryside of Christ Church Parish, in places like Ten Mile and Scanlonville, could travel across the river to sell sweetgrass baskets and fresh-picked flowers. Island children could even attend school in Charleston. The advent of a large-scale, reliable mass transit system across the Cooper River in the late 1890s transformed the mobility of the people living to the east of that big stream. In many ways, it marked the beginning of the modern era of development for what we now call the “East Cooper” community.

You might have noticed, however, that there are no longer any trolleys on those islands, nor any ferries to connect East Cooper with Charleston. So when did these services disappear from the local transportation landscape? About eleven months ago, I created a pair of podcasts about “The First Century of Ferry Service across the Cooper River” (Episode 67) and “The Zenith and Decline” (Episode 68) of that service. In the second of those episodes, I talked about the chain of events that led to the demise of the Cooper River ferry in the infancy of the automobile age. The disappearance of the Seashore trolley system was wrapped up in that drama, so I’ll recap a bit of the story to refresh your memory.

In February 1913, fourteen years after buying out its competitors, the Charleston Consolidated company sold its ferry and island trolley business to the Isle of Palms Traction Company. That new company, owned by Joseph Sottile of Charleston’s well-known amusement family, continued to run both the ferry line from Charleston to Mount Pleasant and the electric trolley from the village to Sullivan’s Island and the Isle of Palms.[12] Other than noticing the change of ownership, ferry customers saw little change in the service or equipment, and so there was no reason to suspect a change was looming on the horizon. In retrospect, however, the residents of Charleston, Mount Pleasant, and the neighboring islands were enjoying the last, halcyon days of ferry service in the early days of the roaring twenties.

Between the late 1910s and early 1920s, the financial stability of the Isle of Palms Traction Company was gradually undermined—not by a loss of customers, but by the settlement of several personal injury lawsuits related to the company’s trolley service.[13] Suddenly, on February 21st 1924, the Sheriff of Charleston County closed the trolley-and-ferry company as part of a large-scale seizure of the Traction Company’s rolling (and floating) stock. Commuters to and from Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island immediately clamored for service. Without an automobile bridge connecting the islands to the mainland, or a bridge over the Cooper River, the trolleys and ferries were their principal means of communicating with urban Charleston and all points west of the Ashley River.[14] As you can imagine, the public was angry, and their elected representatives listened. Two weeks after the closure of the Cooper River ferry service, the South Carolina legislature ratified an act on March 5th 1924 to create the state’s first public ferry entity, called the Cooper River Ferry Commission. The state empowered the commission to spend up to $500,000—a huge sum at the time—to build and maintain ferry infrastructure to expedite traffic across the Cooper River.[15]

Between 1924 and 1930, the Cooper River Ferry Commission spent a lot of public money to develop new ferry infrastructure. Only a tiny portion of those funds was spent on resuscitating the island trolley service, however, for two reasons: First, the ferry commission sold the trolley rights and infrastructure to a new concern—the Mount Pleasant Railroad Company; and second, because the age of the automobile was in full swing by the mid-1920s. In late 1924 and early 1925, the ferry commission completely rebuilt the 1898 trolley bridge connecting Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island. They transformed it into a new asphalt roadway suitable for automobiles and trucks, but they also included a set of trolley tracks in the structure. The new Cove Inlet bridge, as it was then called, opened on July 3rd 1925, and trolley service between Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island resumed one month later, in early August. The trolley no longer traveled to the Isle of Palms, however, because the trestle bridge across Breach Inlet collapsed in early 1925 and was not rebuilt.[16]

Between 1924 and 1930, the Cooper River Ferry Commission spent a lot of public money to develop new ferry infrastructure. Only a tiny portion of those funds was spent on resuscitating the island trolley service, however, for two reasons: First, the ferry commission sold the trolley rights and infrastructure to a new concern—the Mount Pleasant Railroad Company; and second, because the age of the automobile was in full swing by the mid-1920s. In late 1924 and early 1925, the ferry commission completely rebuilt the 1898 trolley bridge connecting Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island. They transformed it into a new asphalt roadway suitable for automobiles and trucks, but they also included a set of trolley tracks in the structure. The new Cove Inlet bridge, as it was then called, opened on July 3rd 1925, and trolley service between Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island resumed one month later, in early August. The trolley no longer traveled to the Isle of Palms, however, because the trestle bridge across Breach Inlet collapsed in early 1925 and was not rebuilt.[16]

On November 1st, 1927, fourteen months after its resumption of trolley service to Sullivan’s Island, the Mount Pleasant Railroad Company “temporarily” ceased operations. After negotiating with the state railroad commission in August of 1928, however, the company decided to liquidate its assets and disappear permanently. The automobile had reached a point of domination in the Lowcountry, and it was pointless to fight against the advance of the new machines. The Cooper River ferry, operated by the state-funded commission, continued to run for several more years, but the opening of the first Cooper River Bridge in August of 1929 sounded the death knell for that service as well.[17]

In the present landscape of Sullivan’s Island and Mount Pleasant, some ninety years after the demise of the electric trolley service, there are only a few remaining vestiges of that transportation era. The rails are gone (mostly), and old power plant on the island was dismantled. The “car barn” in the old village of Mount Pleasant disappeared around 1960. The 1898 bridge across Cove Inlet, which was rebuilt in 1925, proved to be an obstacle to the construction of the Intracoastal Waterway, which commenced in 1929 to create a more robust inland passage behind Sullivan’s Island. To accommodate the needs of island drivers, intracoastal sailors, and the U.S. Department of Defense, the state highway department and federal government built a new causeway through the extensive marsh between Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island. That project, now called Ben Sawyer Boulevard, commenced in 1940 and was finally completed in June of 1945. The old Cove Inlet trestle bridge, known today as the Pitt Street Bridge, is now a picturesque ruin that terminates halfway over the water between the Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island.[18]

Longtime listeners and readers of the Charleston Time Machine will remember that I’ve done a series of programs about transportation history over the past many years. Personally, I’m most comfortable with my head stuck in the eighteenth century, but traffic and mobility are critical issues facing the Lowcountry today, and I’m happy to lend my skills to help raise awareness about earlier modes of transportation in our community. May is national Mobility Month, and, in collaboration with Charleston Moves, I’ll be presenting another program about the rise and fall of omnibuses, street cars, bicycles, trolleys, and diesel buses in urban Charleston. As we move together into the future, a glance back to the past often helps us to see the path forward a bit more clearly.

[1] Michael E. Stevens and Christine M. Allen, Journals of the South Carolina House of Representatives, 1791 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1985), 164–65 (31 January 1791).

[2] See Hibben’s advertisement in the [Charleston] City Gazette, 18 April 1792; and the advertisement for the steamboat South Carolina in Southern Patriot, 2 June 1820.

[3] See Section 16 of “An Act to establish certain roads, bridges and ferries,” ratified on 20 December 1828, in The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 9 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1841): 582. See also, for example, advertisements in the Charleston Courier, issues of 9 June 1828 and 14 May 1830.

[4] This business was chartered in 1848 as the Mount Pleasant Ferry Company, but by August 1852 had become the Mount Pleasant and Sullivan’s Island Ferry Company. In the Charleston Mercury, 19 January 1857, the company announced the discontinuation of its trips to Sullivan’s Island. On 21 December 1857, the state legislature granted a charter to a new ferry business called The Sullivan’s Island Steam Boat Company. According to Charleston Daily News, 21 April 1870, page 4, these two companies merged under a new state charter in March 1870.

[5] See Charleston News and Courier, issues of 13 April 1875 (page 4); 15 June 1875 (page 4); 29 June 1875 (page 4); 20 July 1875 (page 4).

[6] See the Charleston News and Courier, 25 January 1885 (page 3); The Street Railway Journal 2 (February 1886): 80; Charleston News and Courier, 22 October 1887 (page 8). The details of the mercurial history of the New Brighton Hotel are too numerous to elaborate here, but they were all reported in the contemporary local and regional newspapers.

[7] Charleston News and Courier, issues of 11 March 1898 (page 8); 28 March 1898 (page 8); 20 May 1898 (page 8); 13 June 1898 (page 8).

[8] The local papers were full of new about this project in the spring of 1898. See, for example, Charleston News and Courier, issues of 11 March (page 8); 14 March (page 5); 28 March (page 8); 20 May (page 8); 13 June (page 8); 25 July (page 8).

[9] Charleston Evening Post, 28 July 1898, page 4: “With the Heavy Battery.”

[10] Charleston Evening Post, 28 July 1898, page 4: “The Trolley Road Open”; Charleston News and Courier, 29 July 1898, page 8: “Great Event for the City”; Charleston News and Courier, 8 August 1898, page 6, “The News of a Great State.”

[11] Charleston Evening Post, 20 February 1899, page 5: “Winding Up the Big Deal”; Charleston News and Courier, 7 April 1899, page 8: “Stockholders Accepted It.”

[12] See News and Courier, 16 February 1913, page 6: “Seashore Line Changes Hands.”

[13] A number of suits were described in the local newspapers. See, for example, the case of White v. Traction Company (in Charleston News and Courier, 17 January 1919, page 5), Boyd v. Traction Company (in News and Courier, 5 December 1919, page 2), and finally Crawford v. Traction Company (in News and Courier, 26 October 1921, page 6; and Evening Post, 13 January 1923, page 3), which sank the ferry service.

[14] See the front page of Charleston Evening Post, 22 and 23 February 1924; Charleston News and Courier, 25 February 1924, page 10.

[15] See “A Joint Resolution to create a Cooper river Ferry Commission,” ratified on 5 March 1924, in Acts and Joint Resolution of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina Passed at the Regular Session of 1924 (Columbia, S.C.: Gonzales and Bryan, 1924), 1558–62.

[16] Charleston Evening Post, 6 April 1925, page 2: “Cove Inlet Job Progressing”; Charleston Evening Post, 8 April 1925 (Wednesday), page 12: “Car Tracks at Cove Inlet”; Columbia [S.C.] Record, 3 July 1925, page 6: “Commission Accepts Cove Inlet Bridge”; The State [Columbia, S.C.], 16 September 1925, page 2: “Syndicate Buys Isle of Palms.”

[17] Charleston Evening Post, 30 July 1925, page 8: “Car Service to Sullivan’s Isl.”; Charleston Evening Post, 31 August 1928, page 2: “Is Suspended Permanently.”

[18] Charleston News and Courier, 16 March 1940, page 7: “Cove Inlet Span Given Applause”; Charleston News and Courier, 20 June 1945, page 9: “U.S. Paid for Sawyer Bridge; Opening Ceremony Tonight.”

PREVIOUS: Abraham the Unstoppable, Part 6

NEXT: Abraham the Unstoppable, Part 7

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments