The Story behind Ropemaker’s Lane

Processing Request

Processing Request

Ropemaker’s Lane is a narrow alley in urban Charleston with a name that evokes images of an antique industry wrought by men twisting and spinning long fibers into useful objects. While that scenario is accurate, it represents just one facet of the long and colorful history of this quaint locale. To gain a fuller picture of the lane’s development over the past two-and-a-half centuries, lets reach back to early days of the town and meet the people who created the lane and crafted the ropes that inspired the present name.

Ropemaker’s Lane was not part of the original settlement of Charleston. The early plan for the town, created in the 1670s, included more than 300 numbered lots, mostly one-half of an acre in size, and fewer than a dozen streets. In the early days of the town’s development, a number of property owners opened private courts, alleys, and lanes by sacrificing a few feet of land, usually in conjunction with their adjacent neighbors, to create passageways that made it easier to subdivide their half-acre lots. These private passageways, through common usage, eventually became public streets. Ropemaker’s Lane is one such example. It was created to divide Town Lot No. 53, located on the east side of Meeting Street, one hundred feet north of Tradd Street, into two equal halves. The lane, really more of a dead-end court, extends eastward from Meeting Street approximately 245 feet in length, and today it’s approximately ten feet wide.

Although there are no surviving records that tell us precisely when Ropemaker’s Lane was created, I’ve narrowed down the time frame of its birth to a period of about ten years. I feel confident in stating that it was created sometime during the 1740s, and I’ll tell you how I arrived at that conclusion. The boundaries of the several town lots on the east side of Meeting Street, between Tradd and Broad Streets, were measured by a surveyor on the 8th day of March, 1734/5, and recorded in a manuscript notebook that now resides at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia. According to that 1735 survey, Lot No. 53 had been divided into two equal parts, each measuring fifty feet along the east side of Meeting Street. Mr. John Milner owned the southern half of the lot, while the Witter family (of James Island) owned the northern half. The surveyor, who was very attentive to details and anomalies, made no mention of an alley or passageway between their respective half-lots.[1] A few years later, in 1739, Bishop Roberts published a very detailed map of urban Charleston, which he called The Ichnography of Charles Town. A close look at the east side of Meeting Street on that map shows a dotted line in the approximate location of what is now Ropemaker’s lane, but this line probably represents a wooden fence. John Milner, the owner of the southern half of Lot No. 53, died in the autumn of 1749, and a small part of that property was sold in December of 1750. The text of that property conveyance mentions the presence of a small alley way bounding on the north side of Mr. Milner’s lot.[2] In short, there was no alley there in 1739, but it was present by 1750. It must have been created sometime during the 1740s.

Now that we have an approximate date for this historic passageway, what can we say about its purpose. It’s now called Ropemaker’s Lane, but that name was adopted in 1956. Prior to that time, from the 1780s to the 1950s, this narrow lane was called Rope Lane, and sometimes erroneously called Roper’s Lane. Prior to the 1780s, however, I have not been able to find a name attached to it. In fact, we have very little documentary evidence of how the lane and the adjoining properties were being used around the middle of the eighteenth century when it was created. Personally, I suspect that it might have been called Milner’s Lane, or court or alley, because property owner John Milner was the person mostly likely to benefit from its creation. John Milner (died 1749) was part of a family that had been in Charleston since at least the 1690s. He was a gunsmith by trade, and owned a narrow slice of property in urban Charleston that stretched from the west side of Church Street westward to the east side of Meeting Street. This property represented the southern half of Town Lot No. 72 (fronting approximately fifty feet on Church Street), and the southern half of Lot No. 53 (fronting 50 feet on Meeting Street). To help orient you, I’ll mention that the Milner family sold their part of Lot No. 72 to the Heyward family in 1768, and it is now known as the Heyward-Washington House, at what is now No. 87 Church Street.

Now that we have an approximate date for this historic passageway, what can we say about its purpose. It’s now called Ropemaker’s Lane, but that name was adopted in 1956. Prior to that time, from the 1780s to the 1950s, this narrow lane was called Rope Lane, and sometimes erroneously called Roper’s Lane. Prior to the 1780s, however, I have not been able to find a name attached to it. In fact, we have very little documentary evidence of how the lane and the adjoining properties were being used around the middle of the eighteenth century when it was created. Personally, I suspect that it might have been called Milner’s Lane, or court or alley, because property owner John Milner was the person mostly likely to benefit from its creation. John Milner (died 1749) was part of a family that had been in Charleston since at least the 1690s. He was a gunsmith by trade, and owned a narrow slice of property in urban Charleston that stretched from the west side of Church Street westward to the east side of Meeting Street. This property represented the southern half of Town Lot No. 72 (fronting approximately fifty feet on Church Street), and the southern half of Lot No. 53 (fronting 50 feet on Meeting Street). To help orient you, I’ll mention that the Milner family sold their part of Lot No. 72 to the Heyward family in 1768, and it is now known as the Heyward-Washington House, at what is now No. 87 Church Street.

Beginning in March of 1735 until his death in 1749, John Milner had a contract with the provincial government of South Carolina to clean, maintain, and repair the public arms belonging to the colony. These arms included hundreds of muskets, pistols, cutlasses, bayonets, and cartridge boxes. Since we did not yet have an armory or arsenal in which to store these items, Milner received extra money from the government to store the public small arms on his property. During the great fire that destroyed approximately one-third of urban Charleston in November of 1740, John Milner watched his own house fronting Church Street burn to the ground while he was busy moving the public arms to a more secure location. [3] He rebuilt his house on Church Street in 1741, and by the beginning of 1742, Milner was once again storing hundreds of small arms on his property. Just over a year later, near the end of 1743, the government of South Carolina finally completed construction of a brick armory building on the west side of Meeting Street, just a bit south of Broad Street, and finally Milner was able to remove the public arms from his site to the new storage facility. According to an inventory made around the time of that transfer, Milner had in his possession 860 muskets in good order with bayonets fixed, 408 guns in good order without bayonets, 81 clean guns out of repair, 15 guns not worth repairing, 152 cutlasses in good order with scabbards, 22 cutlasses wanting scabbards, 76 clean bayonets, 32 pistols out of repair, and 448 cartridge boxes. From that time until his death, John Milner continued to hold a contract for repairing the public arms, and held the title of armorer for the province of South Carolina.[4]

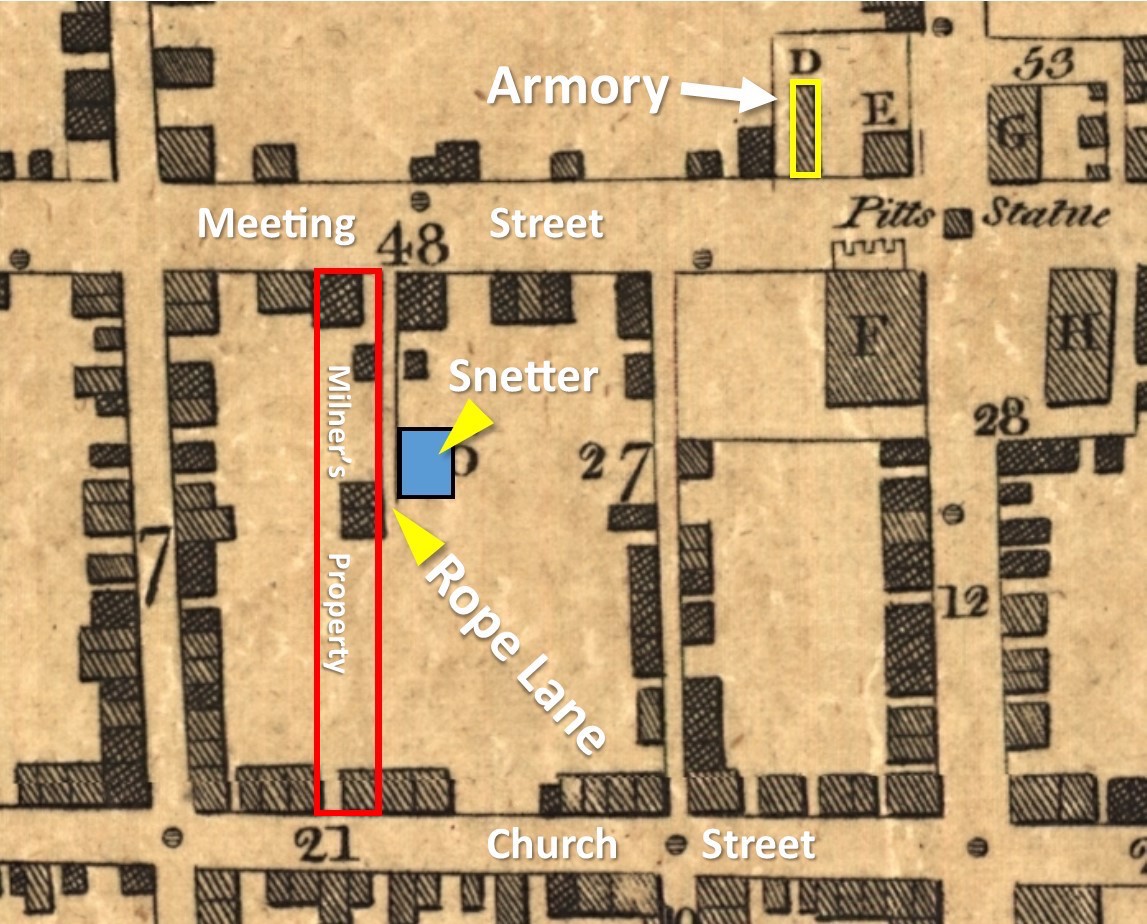

In conjunction with today’s episode, I’ve created a graphic showing the location of John Milner’s property, Ropemaker’s Lane, and the new public armory that was completed in 1743. I’ve taken the Ichnography of Charleston, published by the Phœnix Fire Insurance Company of London in 1790, but based on a survey made in 1788, and added notations to help illustrate a point. John Milner had a gunsmithing workshop and forge on his property, nearly midway between Church and Meeting Streets, and his residence faced Church Street. With the opening of the new armory on Meeting Street in 1743, he moved more than 1,000 small arms to the new facility, and his duties as public armorer required him to make frequent trips between his workshop and the armory. The shortest route between those two points is, of course, through Lot No. 53 to Meeting Street. Although I have not found any documentation confirming this route, I feel confident that Milner’s work would have been greatly simplified by the creation of this narrow passageway through his own property sometime between the opening of the armory 1743 and his death in 1749.

Between 1750 and the onset of the American Revolution in 1775, I have not found any evidence of how Milner’s narrow passageway was being used, or any sort of name attached to it. That situation changed in the autumn of 1781 when a white man named Charles Snetter purchased a long-term lease on a small parcel of land located at the northeast end of the unnamed alley. Snetter, whose background is a mystery to me, leased a piece of ground measuring 46 feet wide (north-south) and 58 feet 9 inches deep (east-west), which was recessed nearly 200 feet east of Meeting Street.[5] The contract identified Charles Snetter as a “rope maker of Charles Town,” but I haven’t been able to find any record of his presence here prior to the Revolution. He seems to have appeared during the British occupation of Charleston, and, as a loyalist, may have come here from England or from another colony. By the 1790s, however, he was an established citizen of the town and a member of a local militia group called the Charleston Battalion of Artillery.[6] Regardless of the details of his background, Charles Snetter constructed several wooden buildings on his small lot and established a rope-making business in the autumn of 1781. That fact marks the point at which this narrow passageway acquired an early version of its current moniker. The 1790 Ichnography of Charleston, which was based on a survey made in 1788, identifies the passageway leading to Snetter’s shop as “Rope Lane,” which measured 7 feet 6 inches wide.

Between 1750 and the onset of the American Revolution in 1775, I have not found any evidence of how Milner’s narrow passageway was being used, or any sort of name attached to it. That situation changed in the autumn of 1781 when a white man named Charles Snetter purchased a long-term lease on a small parcel of land located at the northeast end of the unnamed alley. Snetter, whose background is a mystery to me, leased a piece of ground measuring 46 feet wide (north-south) and 58 feet 9 inches deep (east-west), which was recessed nearly 200 feet east of Meeting Street.[5] The contract identified Charles Snetter as a “rope maker of Charles Town,” but I haven’t been able to find any record of his presence here prior to the Revolution. He seems to have appeared during the British occupation of Charleston, and, as a loyalist, may have come here from England or from another colony. By the 1790s, however, he was an established citizen of the town and a member of a local militia group called the Charleston Battalion of Artillery.[6] Regardless of the details of his background, Charles Snetter constructed several wooden buildings on his small lot and established a rope-making business in the autumn of 1781. That fact marks the point at which this narrow passageway acquired an early version of its current moniker. The 1790 Ichnography of Charleston, which was based on a survey made in 1788, identifies the passageway leading to Snetter’s shop as “Rope Lane,” which measured 7 feet 6 inches wide.

Eighteenth-century Charleston boasted the presence of several rope manufactories, as would be expected of any bustling seaport. According to numerous references to “rope works” or “rope walks,” as they were known, in early Charleston newspapers and in land conveyances, the manufacture of rope generally took place outside the city limits. The creation of very long ropes and cables for the maritime business required a long, narrow piece of real estate on which one could twist and braid hemp fibers into threads, threads into ropes, and ropes into cables. Think of ships’ rigging, anchor cables, and docking lines. To make these fiber ropes waterproof for marine use, they needed to be coated in tar, which had to be boiled on site. This was not an especially pleasant industry, so Charleston’s marine ropeworks were always located beyond the residential areas, just north of Boundary Street (now Calhoun Street). Captain James Reid’s long and narrow rope walk, for example, is now Reid Street.

The rope manufactory established by Charles Snetter in 1781 was a different sort of business, however. In several of his newspaper advertisements in the 1790s, Snetter described himself as a “white rope” maker (and he wasn't talking about the color of his skin). In short, Snetter did not make long, black, tar-coated ropes suitable for marine use. He made a variety of narrow-gauge strings, twine, and ropes for domestic use, using threads of both cotton and silk. At his small “rope walk” near St. Michael’s Church, he offered such things as halter and bridle ropes, curtain lines, packing twine, drum cords, sewing twine, shoe maker’s thread, surgeon’s tow, fishing lines, and lines with which to make casting nets and fishing seines.[7]

When Charles Snetter, “rope and line maker,” made his will in the spring of 1799, he had neither wife nor children. He owned a piece of property on upper King Street, where he apparently resided, but he did not own the property on which he had built his business on Rope Lane. He bequeathed his two-story house and lot on King Street to the Charleston Orphan House, for the support of unfortunate children. In setting out the future of his commercial estate, however, Snetter turned to the enslaved people who had helped him build the business. “[I] give my negro man Brister [Bristol] his freedom and emancipate him for ever from slavery[,] and also give him all my tools for rope making and twine spinning.” Turning next to a woman who may have been Bristol’s wife, Charles Snetter added, “[I] emancipate my negro woman slave named Sarah, give her free also a legacy of ten pounds out of my estate for her to begin the world with.”[8]

Charles Snetter, the white “white rope” maker, died in the spring of 1802, but his rope-making business continued for nearly two decades longer under the management of Bristol Snetter, the enslaved man freed in the will of his former master. I haven’t been able to find anything about the life of Bristol, whose name was occasionally spelled in the newspapers and city directories as “Brister.” Bristol and Sarah Snetter apparently lived on the site of their rope manufactory, and raised family there as well. Although we know nothing about his origin or age, Bristol died sometime in late 1820 or early January 1821, during a period in which there is a gap of several months in the surviving death records of the City of Charleston at CCPL. On the fifth day of February, 1821, an auctioneer presided over a sale of Bristol Snetter’s workshop in “Rope Alley” and dismantled the forty-year-old business. On sale that day were “sundry articles of household and kitchen furniture” as well as two wooden buildings that were to be removed within ten days after the sale.[9]

Following Bristol’s death and the sale of their rented home, the widow Sarah Snetter had to move elsewhere, but her exact movements are unknown. According to the city’s weekly death ledgers, a sixty-year-old free “black” woman named Sarah Snetter died at the city’s Poor House on April 17th, 1823, and was buried at the public “C[ity] B[urial] G[round].” She had at least one child, named Charles Snetter, who worked as a barber in urban Charleston.[10] In the early 1830s, Charles Snetter became interested in the efforts of the American Colonization Society, founded in 1816 with a mission to assist Americans of African descent to emigrate to a new colony in Africa, called Liberia. Snetter expressed a desire to move to Liberia and stated that he had an aunt in Savannah who was born in Africa and also desired to return to the land of her birth. Whether that woman in Savannah was the sister of Snetter’s father, Bristol, or his mother, Sarah, is unknown. The city’s death record for Sarah Snetter described her as a native of Charleston, but that information may have been erroneous. In the spring of 1832, the young barber Charles Snetter moved with his wife and children to Liberia, where he died in 1840, but the surname Snetter continued to exist among Charleston’s African American population well into the twentieth century.[11] If you type the phrase “Charles Snetter” and “Liberia” into Google, you’ll find a gentleman of that name who’s a radio and music producer in present-day Liberia. Small world, eh?

The rope-making enterprise launched by Charles Snetter in 1781 went out of business in 1821, but the name “Rope Lane” or “Rope Alley” continued in the Charleston lexicon for many more years. In some later nineteenth- and twentieth-century records, you’ll find it erroneously spelled as “Roper’s Lane.” To be sure, there were no members of the Roper family associated with this property (they were a bit farther north, briefly on Lot No. 54). The small, subdivided lots on the north and south sides of Rope Lane were eventually consolidated into larger lots, and covered with grander houses occupied by wealthier folks. In an effort to end the confusion over the passageway’s nomenclature, the City Council of Charleston ratified an ordinance on August 21st, 1956, that struck down the name “Roper’s Court” and officially adopted the name “Rope Maker’s Lane.”[12]

Shortly after the official renaming of the lane in 1956, someone created a marble tablet with the engraved text “Ropemakers Lane,” and placed it a new brick column standing at the northwest end of the lane. Millions of tourists have walked past that sign in the past half-century and peeked down the narrow passageway hoping to catch an imaginary glimpse of of life in early Charleston. The next time you’re in the neighborhood, I encourage you to take a stroll back in time here. Imagine the gunsmith John Milner and his team of enslaved assistants toting muskets and cutlasses to and from the town’s colonial armory. Think of the white rope maker, Charles Snetter, selling fishing lines and shrimp nets to members of our Mosquito Fleet. Consider, too, the life of Bristol and Sarah Snetter, who lived and worked in slavery and freedom at the northeast end of the alley during the early years of the nineteenth century, and raised a young boy named Charles Snetter who fulfilled his dream of returning to Africa. Everywhere you look in Charleston, there’s a deep story populated with characters I’d like to meet. They’re all gone now, but at least I have this Time Machine.

[1] South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Surveyor’s Notebook for Charleston, page 53 (folio 29, recto). The surveyor measured “Mr. Milner’s front of his house which part he bought of Mr. Macnabney,” but he did not provide a first name for the “Mr. Witter” who owned the northern half of Lot No. 53. Milner and Witter apparently each ceded a few feet of land to create the lane, as each of their respective lots was described in later conveyances as measuring a bit less than fifty feet.

[2] Charleston County Register of Deeds, NN: 266–79: John Milner Jr. and Bathsheba, his wife, and Solomon Milner and Mary, his wife, to John Hodson, lease and release, 3–4 December 1750. This conveyance describes Milner’s half of Lot No. 53 as descending through the heirs of Jeremiah Milner.

[3] Martha Zierden and Elizabeth J. Reitz, Charleston through the Eighteenth Century: Archaeology at the Heyward-Washington House Stable. Archaeological Contributions 39 (Charleston, S.C.: Charleston Museum, 2007), 13–15

[4] John Milner, gunsmith, received a contract for cleaning and maintaining public arms on 5 March 1734/5; see Alexander S. Salley Jr., ed., Journal of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina, November 8, 1734–June 7, 1735(Columbia: Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1947), 86. On 13 November 1736, the Commons House ordered Lt. Gov. Broughton to order John Milner to take possession of “the public arms . . . that they may be kept secured in a proper place, which he has already prepared for that purpose”; see J. H. Easterby, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, November 10, 1736–June 7, 1739(Columbia: Historical Commission for South Carolina, 1951), 18. On 2 February 1739/40, John Milner submitted a bill for “cleaning and mending the public arms, and the rent of a room to keep the public arms”; in the fire of November 1740, John Milner’s house and workshop were destroyed, but he saved the public arms by moving them to the attic space above the Council Chamber (where the Exchange stands today); see J. H. Easterby, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, September 12, 1739–March 26, 1741(Columbia: Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1952), 169, 479. By the beginning of 1742, Milner had the public arms back in his possession; see J. H. Easterby, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, May 18, 1741–July 10, 1742(Columbia: Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1953), 435. Milner reported the abovementioned inventory of arms on 25 January 1743/4; see J. H. Easterby, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, September 14, 1742–January 27, 1744(Columbia, South Carolina Archives Department, 1954), 546.

[5] Charleston Country Register of Deeds, F5: 445–47: John Sommers the younger of Charles Town to Charles Snetter, rope maker of Charles Town, lease for six years, 1 September 1781. I found no recorded renewal of this lease, but apparently it was renewed to at least 1800 (see below).

[6] Snetter mentioned his membership in the artillery in his will, dated 28 March 1799, proved 3 June 1802; see WPA transcript volume No. 28 (1800–7), 296–97, at CCPL. Snetter’s signature also appears on a petition submitted by the Charleston Battalion of Artillery to the state legislature in 1800; see SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, 1800, No. 69, No. 70.

[7] See, for example, Snetter’s advertisements in [Charleston] City Gazette, 9 March 1795; City Gazette, 5 March 1796.

[8] Will of Charles Snetter, dated 28 March 1799, proved 3 June 1802; see WPA transcript volume No. 28 (1800–7), 296–97, at CCPL. Philip Hillegas qualified as executor. Prior to his death, Charles Snetter executed another lease relating to Rope Lane. See Charleston County Register of Deeds, F7: 158–59: John McIver to Charles Snetter, lease for five years, dated 8 April 1800. This lease included a piece of land on the north side of “Rope lane” measuring 46 feet north-south and 93 feet along the alley, east-west; which piece of land is bounded to the north by Samuel Prioleau; to the south by Rope lane, to the east by ____ [blank in original]; and to the west on land of John McIver. From this description, it is unclear if the property described in 1800 represented a second parcel of land, or simply a renewal of an enlarged parcel of land from McIver, who had apparently bought out John Sommers. I did not find a recorded renewal of this five-year lease, but apparently such renewals were made with Bristol Snetter.

[9] [Charleston] City Gazette, 5 February 1821.

[10] For an example of Charles Snetter’s career, see Charleston Courier, 12 May 1828: “Barber Wanted. A first rate shaver and hair dresser, will find good and respectable employment, and wages, paid punctually, by applying at No. 92 Market-st. near King. The subscriber returns his thanks to the public for their attention, and hopes a continuance of the same. ¶ Charles Snetter. ¶ May 12.”

[11] See William Innes, Liberia: Or the Early History & Signal Preservation of the American Colony of Free Negroes on the Coast of Africa (2nd ed., London: Whittaker & Co., 1833), 186; Toyin Falola and Kwame Essien, eds., Pan-Africanism, and the Politics of African Citizenship and Identity (New York: Routledge, 2014), 32–33. A much fuller account of Charles Snetter’s life in Liberia (and his violent death) is presented by Erskine Clarke in By the Rivers of the Water: A Nineteenth-Century Atlantic Odyssey (New York: Basic Books, 2013).

[12] See the printed volume of Proceedings of Charleston City Council, 1955–59, 60–61. See also Charleston News and Courier, 22 August 1956.

PREVIOUS: Charleston: The Palmetto City

NEXT: The Earliest Fortifications at Oyster Point

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments