The Stono Rebellion of 1739: Where Did It Begin?

Processing Request

Processing Request

In early September 1739, dozens of enslaved men residing near the Stono River launched a violent campaign to gain their freedom. The events of that bloody uprising, commonly called the Stono Rebellion, form a pivotal and well-known episode in the history of South Carolina, but our understanding of its geography is imperfect. In this episode of Charleston Time Machine, we’ll review the documentary clues relating to the path of the rebellion and propose a new interpretation of its point of origin.

The Stono Rebellion, which claimed perhaps a hundred lives, both Black and White, was unquestionably one of the seminal events in the history of South Carolina. It occurred within a context of great anxiety among South Carolina’s White population about the colony’s growing majority of enslaved people of African descent, which reached a point of peak African-ness in the year 1740 (see Episode No. 99). Besides a general contempt for the conditions of slavery, the rebels of 1739 were also inspired by promises of freedom from Spanish officials in nearby Florida. That international provocation was part of mounting Anglo-Spanish tension that erupted into a formal declaration of war several weeks after the uprising (see Episode No. 216 ).

The narrative of the Stono Rebellion is also a fixture within the canon of South Carolina historiography. Over the past half-century, numerous scholars have published summaries of the bloody events, explored the socio-political context of the uprising, and documented its enduring influence through the later history of the Palmetto State. In 2005, for example, the University of South Carolina Press published a very useful book, edited by Mark M. Smith, titled Stono: Documenting and Interpreting a Southern Slave Revolt. That small but valuable book includes transcriptions of the most pertinent primary sources related to the events of 1739, from which generations of scholars have drawn conclusions and inspiration.

My esteemed colleagues in the history field have enlightened us about many aspects of the uprising, answering our questions about who, what, when, why, and how, for example, while saying very little about where on the landscape these events unfolded. Rather than attempt to summarize the excellent work done by other scholars, I’d like to focus our attention on the largely unexplored geography of the Stono Rebellion—especially its point of origin and the cardinal directions of its progress.

My inspiration for exploring this topic comes from a close reading of the primary source materials describing the events of September 9th and 10th, 1739. Some might find it surprising to learn that most of what we know about the names of the victims and the geography of the Stono Rebellion comes from just one surviving source—a letter written in Charleston in October 1739 and published in London in March 1740 as an “Account of the Negroe Insurrection in South Carolina.” In case you don’t have that source at your fingertips, I’ll quote the most pertinent text (with the original spelling):

“On the 9th day of September last, being Sunday, which is the day the planters allow them to work for themselves, some Angola Negroes assembled, to the number of twenty, and one who was called Jemmy, was their captain, they supriz’d a warehouse belonging to Mr. Hutchenson at a place called Stone how [sic; Stono]; there they killed Mr. Robert Bathurst, and Mr. Gibbs, plunder’d the house, and took a pretty many small arms and powder, which were there for sale. Next they plunder’d and burnt Mr. Godfrey’s house, and kill’d him, his daughter and son. Then they turned back, and marched southward along Pons Pons, which is the road through Georgia to [Saint] Augustine, they passed Mr. Wallace’s Tavern about day-break, and said, they would not hurt him for he was a good man and kind to his slaves; but they broke open and plundered Mr. Lemy’s House, and kill’d him, his wife, and child. They marched on towards Mr. Rose’s, resolving to kill him; but he was saved by a Negroe, who having hid him, went out and pacified the others. Several Negroes joined them, they calling out Liberty, marched on with colours displayed, and two drums beating, pursuing all the white people they met with, and killing man woman and child, when they could come up to them. Colonel Bull, Lieutenant-Colonel [sic; Governor] of South Carolina, who was then riding along the road, discovered them, was pursued, and with much difficulty escaped, and raised the country. They burnt Colonel Hext’s house, and killed his overseer and his wife. They then burnt Mr. Sprey’s house, then Mr. Sacheverell’s, and then Mr. Nash’s house, all lying upon the Pons Pons Road, and killed all the white people they found in them. Mr. Bullock got off, but they burnt his house. By this time many of them were drunk with the rum they had taken in the houses. They increased every minute by new Negroes coming to them; so that they were above sixty, some say a hundred, on which they halted in a field, and set to dancing, singing and beating drums, to draw more Negroes to them, thinking they were now victorious over the whole province, having marched ten miles, and burnt all before them without opposition: But the militia being raised, the planters with great briskness pursued them, and when they came up, dismounting, charged them on foot. The Negroes were soon routed, though they behaved boldly; several being killed on the spot, many ran back to their plantations, thinking they had not been missed; but they were there taken and shot; such as were taken in the field, also, were, after being examined, shot on the spot. . . .”[1]

If you follow U.S. Highway 17 around twelve miles west of Charleston towards the town of Ravenel, you’ll pass a state historical marker commemorating the Stono Rebellion on the right-hand side of the road, just after crossing the bridge over Wallace Creek. The name of that body of water represents a valuable link to the events of September 1739. Wallace Creek is named for Thomas Wallace (also spelled Wallis), who operated a tavern and toll bridge at this site from the 1720s until his death in 1745.[2] Mr. Wallace owned 253 acres extending to the southward of this landing, and plats created during the second half of the eighteenth century show a small cluster of buildings standing at the site now occupied by the historical marker.[3]

The known location of Thomas Wallace’s tavern provides a valuable anchor for exploring the geographic scope of the Stono Rebellion. To acknowledge its significance, the site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974, and the present state historical marker was erected in 2006. Those modern commemorations have engendered some confusion, however. While the 1974 National Register nomination inaccurately described the site as “the starting point of the Stono River Slave Rebellion,” the marker erected in 2006 simply states that the Stono Rebellion “began nearby.”[4] By referring back to the aforementioned 1739 description of the uprising, we are reminded that Wallace’s Tavern served as a sort of pivot-point for the rebels. Their initial acts of violence commenced on the evening of September 9th at some other location, after which “they passed Mr. Wallace’s Tavern about day-break.”[5]

From that landmark, the rebels followed the path of a public highway once known as the Pon Pon Road, which was created in the early 1720s to link settlements on the Stono River to those on the Pon Pon or Edisto River.[6] The 1739 description of the uprising includes the names of several families who were attacked in succession as the rebels moved in a southwesterly direction along what we now call Highway 17. Although I have not traced the precise location of each of those homesteads, I feel confident that one could plot most or all of them on a map with sufficient research. Finally, the site of the decisive pitched battled between the rebels and members of the South Carolina militia on September 10th has been called Battlefield Plantation since the mid-eighteenth century, and stands near the northeast side of the intersection of Highway 17 and Parker’s Ferry Road.[7]

In short, there’s little mystery surrounding the geography of the second half of the Stono Rebellion, which unfolded along a fifteen-mile stretch of modern Highway 17. In contrast, however, the path of the initial events is far less clear. Our 1739 source states that the violence commenced at “a warehouse belonging to Mr. Hutchenson at a place called Stone how.” Let’s take a moment to consider the identity of this man and the interpretation of this place name in turn.

There were at least four men named Hutchinson in South Carolina in 1739. Two brothers, John and Thomas, were the young sons of Dr. John Hutchinson (died 1729), both of whom became planters in the Port Royal area rather than merchants. One William Hutchinson styled himself a merchant of Charleston, but left no surviving evidence of commercial activity before his death in July 1739. His estate was settled by a cousin named Ribton Hutchinson, who came to Charleston around the year 1730 and died in 1757 after a prosperous career as a Carolina merchant.[8] Ribton Hutchinson repeatedly advertised the sale of imported goods from a store on East Bay Street, but I can find no evidence that he owned property near the Stono River or operated a store within the orbit of Tom Wallace’s Tavern. I would describe Ribton as a likely candidate for the identity of our “Mr. Hutcheson,” but corroborative evidence is lacking.

Setting aside, for the moment, the identity of the proprietor of the sacked warehouse, we can at least consider its possible location. Some modern narrators of the Stono Rebellion have described “Hutchenson’s warehouse” as being adjacent to or very near Wallace’s Tavern, but that geography is, in my opinion, too narrow. The surviving sources tell us that the uprising commenced not along the Stono River, but at a place simply called “Stono,” a generic term that once embraced a much broader territory.

The sprawling Stono River, named after an extinct band of Native Americans (see Episode No. 220), is almost entirely contained within the modern boundaries of Charleston County. During the colonial era, however, parts of the Stono formed the boundaries between two counties and three parishes. The early inhabitants of the Lowcountry described the Stono as having at least five distinct branches, shaped roughly like an elongated letter X. I’ll describe the branches from the Atlantic Ocean to the headwaters, which is opposite to the direction of their flow. The most visible part of the Stono is the southeast branch, which separates John’s Island from James Island, while the southwest branch connects to the Wadmalaw River and helps define that eponymous island. The middle branch of the Stono stretches like an egret’s neck from John’s Island to the northwest, and was sometimes called the northwest branch. At a point just below Wallace’s Tavern and Wallace’s Bridge, the middle branch forks into a pair of smaller tributaries. What we now call Wallace Creek was formerly known as the western branch of the Stono, while modern Rantowles Creek was once called the north or northeast branch of the Stono. Both of those branches subdivide further into numerous fingers to the north and west, which drain fresh water from Caw Caw Swamp and other inland swamps towards the Atlantic.[9]

From the creation of South Carolina’s first political divisions in 1682, the various branches of the Stono River formed the boundary between Colleton County and Berkeley County (that is, modern Charleston County). When our provincial legislature created a network of parishes across the Lowcountry in 1706 (as described in Episode No. 203), the Stono formed the boundary between St. Andrew’s Parish to the east and St. Paul’s Parish to the west and south. The broad boundaries of St. Paul’s were trimmed in 1734, however, when the legislature designated the islands on the south side of the Stono River to be the separate Parish of St. John’s, Colleton County.

Bearing in mind these political divisions of the landscape, and considering the sprawling branches of the Stono River, let’s reconsider a simple phrase from the autumn of 1739: The rebellion began at “a place called Stone how.” We know that the second half of the uprising unfolded across the landscape of St. Paul’s Parish, Colleton County, but did it begin in the same parish? Did it commence along a different branch of the Stono in St. John’s Parish (that, is on John’s Island), or perhaps on the eastern shores of the Stono in the parish of St. Andrew, Berkeley County? None of the surviving primary-source descriptions of the Stono Rebellion provides any further clarification. So where might we look for Mr. Hutchenson’s warehouse?

Returning to our 1739 description of the uprising, I see an important clue following the description of the initial violence. After plundering Mr. Hutchenson’s warehouse and murdering the family of one Mr. Godfrey, the rebels “turned back, and marched southward along Pons Pons” road. In my mind, that phrase suggests that a literal reversal, or at least a significant change of direction. If the rebels passed Wallace’s Tavern and turned to the southwest at sunrise on September 10th, they must have been traveling in a different direction during the preceding hours. Were there any warehouses or storehouses to the north, east, or southeast of Wallace’s Tavern at that time?

In eighteenth-century South Carolina, as in other communities around the world, rural commercial operations like general stores frequently sprouted at high-traffic sites like river crossings. In 1739, there were at least three public crossings over different branches of the Stono. An act of the provincial government in 1703 authorized the creation of a public highway from the Ashley River to Willtown on the Pon Pon River—a path now called Bee’s Ferry Road and Highway 162. That project involved the creation of bridges over the north and west branches of the Stono, which are now called Rantowles Bridge and Wallace Bridge, respectively. Alexander Rantowle (died 1781) operated a tavern and store at both of these locations in the years after the death of Thomas Wallace. At the time of the Rebellion, the commercial facilities at the north Stono bridge were under the management of Francis Dandridge (died 1758). The name Wallace is familiar to students of the 1739 uprising, but Mr. Dandridge’s name does not appear in any of the contemporary descriptions of the revolt. In the days after the initial violence, however, local militia men gathered at Dandridge’s Tavern and consumed significant quantities of alcohol while they planned their attack on the rebels.[10]

Because the rebels of 1739 did not molest Mr. Dandridge or his establishment, we might conclude that the uprising did not commence in the parish of St. Andrew, to the east of several branches of the Stono River. Several miles due south of Wallace’s Bridge and Tavern, however, there was an early bridge and later a ferry across the southwest branch of the Stono, at a place still called Stono Ferry.[11] This site, connecting John’s Island with the mainland near modern Highway 162, would be a logical place for a tavern, store, and/or warehouse, but I haven’t found any documentary evidence of commercial activity at this site around the year 1739.[12]

Failing to identify “Mr. Hutchenson” or the location of his warehouse, we can turn back to the narrative of 1739 in search of other clues. The enslaved rebels killed one Robert Bathurst and one Mr. Gibbs at the warehouse—men who cannot be positively identified without further information. “Next,” says our primary source, “they plunder’d and burnt Mr. Godfrey’s house, and kill’d him, his daughter and son.” Anyone who has studied the colonial history of South Carolina will recognize that Godfrey was a fairly common and widespread name during the colony’s early generations. By 1739, four generations of Godfreys had spread across the landscape and held property in nearly every parish near the coastline. I spent a number of hours in recent weeks tracing the titles of Godfrey properties near the various branches of the Stono River without finding any compelling clues. Then I remembered conversations some twenty years ago with a recently-departed friend, Joseph LaRoche Rivers. Joe spent much of his retirement years compiling genealogical information about Lowcountry families, and I remembered that he had covered the Godfrey’s quite thoroughly. Turning to his publication on that topic, I found paydirt—a clue to help crack this Stono mystery.

On the last day of June in the year 1749, one William Godfrey submitted a petition to Governor James Glen and his executive Council of advisors in Charleston. William, whose age at that time is unclear, stated that his “father was murthered [sic] with some of his family at his house,” and the family home “with all his papers and deeds [was] burnt by the Negroes in the Negro insurrection” a decade earlier. Godfrey explained that he was “the eldest son” of his late father, and was still “in possession of the land at Stono where his father lived.” “By the said misfortune of burning his fathers house &c. the plat & grant for the said land was as he supposed consumed,” however, and William had been unable to find any record to prove his rightful ownership of the property. As a last resort, he asked the governor to order the Surveyor General to resurvey and regrant the land to him to confirm his family’s possession.[13]

Governor Glen was not in South Carolina at the time of the Stono Rebellion, so he consulted with his local advisors to ascertain the validity of William Godfrey’s story. The councilors confirmed the young man’s account, and the governor granted his request immediately. William had described the property as “containing about four hundred acres lying in St. Pauls Parish,” but the surveyor general of the province determined that the tract in question contained only 375 acres. A small portion of that land was also consumed by a public road that traversed the rectangular tract at a right angle. One year later, Godfrey received a formal grant for the land that his family had occupied for some time before the tragedies of September 1739.[14]

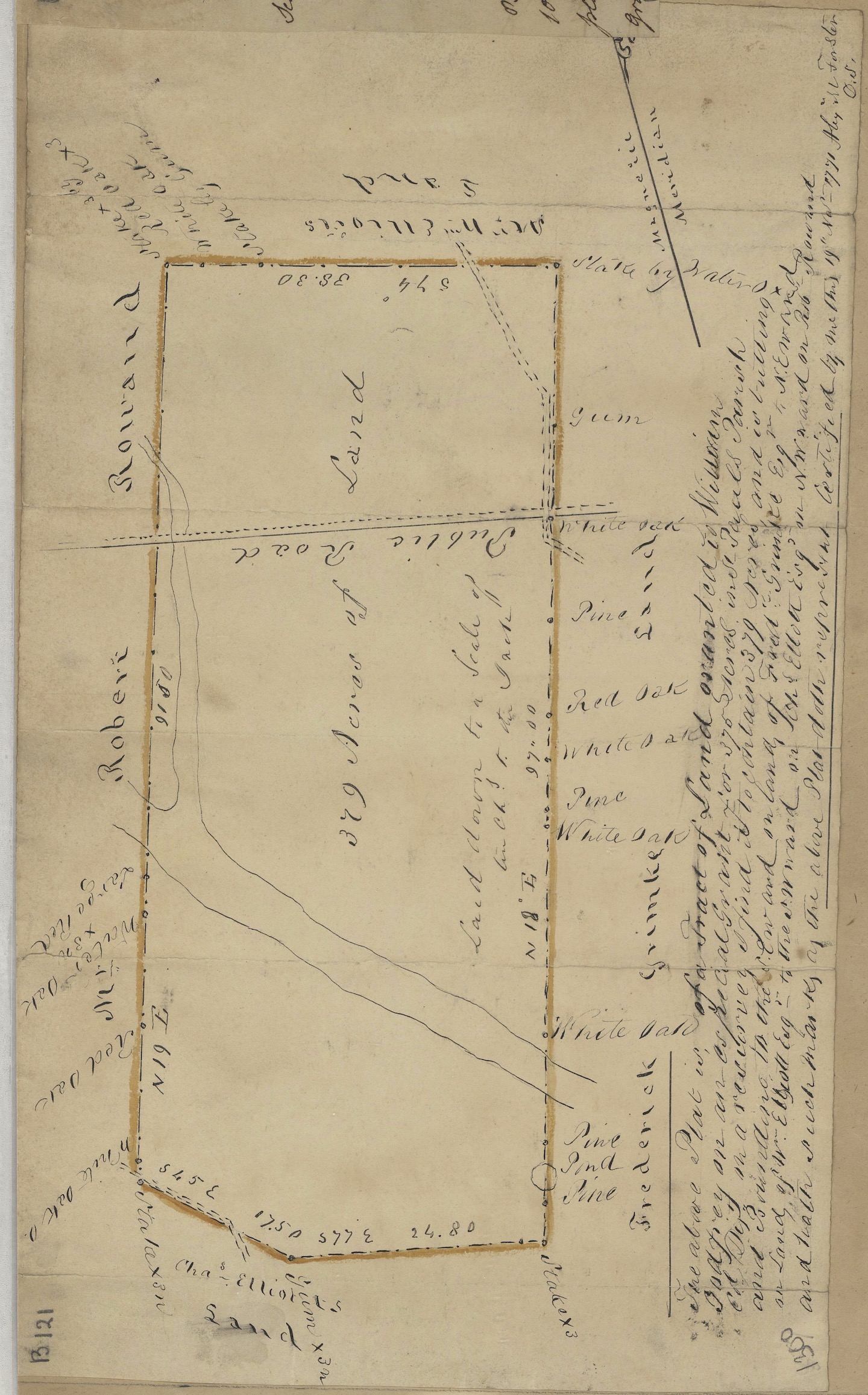

William Godfrey eventually sold his relatively small tract of 375 acres, and Barnard Elliott (1740–1778) advertised it for sale in the autumn of 1771. Elliott described it as “a tract at Stono,” located slightly more than one mile from “the public landing at Friend-Town.”[15] The property changed hands a number of times over the subsequent generations, of course, but a comparison of extant plats provides a clear view of its location on the modern landscape. The tract of land on which members of the Godfrey family were murdered on September 9th, 1739, straddles modern County Line Road—formerly known as the road from Parker’s Ferry to Rantowle’s Bridge—just over a mile due west of a public landing on the north branch of the Stono River, now called Bulow Landing.[16]

While the placement of the Godfrey tract certainly improves our understanding of the geography of the Stono Rebellion, it also suggests a possible location for “Mr. Hutchenson’s” warehouse. The long-standing public dock now called Bulow Landing represents a logical location for a commercial store or warehouse, especially in distant generations when boats were the preferred mode of transportation across the Lowcountry. The early history of Bulow Landing was unknown to me until I noticed a curious coincidence in the 1749 plat of William Godfrey’s tract at Stono. His eastern neighbor at that time was Frederick Grimke (1703–1778) a German-born merchant who emigrated to Charleston in 1733. In the autumn of 1734, Grimke formed a commercial partnership with Ribton Hutchinson. The firm of Hutchinson & Grimke operated a store on the Bay of Charleston, selling a wide variety imported goods like a well-stocked general store. They never advertised the existence of a rural outlet at Stono, but there was far less need to do so when there was little competition outside of the colonial capital.[17]

Out of curiosity, I explored various resources to see what other lands, if any, Frederick Grimke held in the Stono area around the time of the famous uprising. A few years after his arrival in South Carolina, Grimke married Martha Emms Williamson, the youngish widow of a wealthy landowner in St. Paul’s Parish. In addition to gaining lands through her, Grimke acquired, at some point before 1738, a tract of land in St. Andrew’s Parish, on the east side of the north branch of the Stono, immediately opposite what is now called Bulow Landing. The surveyor general then directed a deputy to survey 54.5 acres of vacant marsh between Grimke’s high land and the waters of the Stono’s north branch. Whether or not he received a formal grant for the marsh is unclear to me at the moment, but the implications are intriguing, nonetheless. Thanks to Ribton’s Hutchinson’s mercantile connections and Frederick Grimke’s property portfolio, the firm of Hutchinson & Grimke was well poised to operate a commercial storehouse adjacent to the public depot now called Bulow Landing and delegate its operations to hired hands. Coincidentally, three enslaved men belonging to Frederick Grimke—named Pompey, Tony, and Primas—were rewarded by the provincial government for their timely efforts to suppress the rebellion on September 9th. One must conclude, therefore, that they were very near the scene of the action.[18]

Summarizing the documentary evidence mentioned in this program, I’ll conclude with the following hypothesis: I suspect that the initial acts of violence in the Stono Rebellion of 1739 took place on the evening at of September 9th at a warehouse operated by agents of Hutchinson & Grimke, located in the vicinity of the public waypoint now called Bulow Landing, perhaps within the modern subdivision called Poplar Grove.[19] After murdering two storekeepers and stealing weapons, the core group of rebels likely moved in a northwesterly direction along the public road towards Parker’s Ferry. Approximately one mile into their journey, they passed the Godfrey house and killed several inhabitants. After setting fire to the house, the rebels might have continued their northwesterly trek for some time before deciding to change route. At some point in the dark early-morning hours of September 10th, they “turned back, and marched southward” to Wallace Bridge. The distance from the Godfrey tract is just over three miles along the public road, enabling the rebels to pass Wallace’s Tavern “about day break.” From that geographic point, now designated a National Historic Site and marked with a roadside plaque, the rebels marched southwestward on the Pon Pon Road towards Jackson’s Ferry.

The Stono Rebellion took place in a distant era inhabited by people whose attitudes and behavior we might find quite foreign to our own. The past is a different country, as they say, but we share a landscape with generations of forgotten people who shaped the place we now call home. Although we can’t literally travel back in time, we can strive to make the most of the sparse historical artifacts at our disposal. With a bit of hard work and serendipity, we gain valuable insight and, occasionally, take a metaphorical walk in their faded footsteps.

[1] “Extract of a Letter from S. Carolina, dated October 2,” Gentleman’s Magazine, March 1740 (volume 10): pages 127–29. This material is transcribed as Document 6 in Mark M. Smith, ed., Stono: Documenting and Interpreting a Southern Slave Revolt (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2005), 13–15. Note that an identical narrative was published in The London Magazine, March 1740, page 152. The weekly South Carolina Gazette did not include any information about the uprising in the edition of 8–15 September 1739, and Mrs. Elizabeth Timothy did not publish another edition until 13 October 1739, “by reason of sickness.”

[2] A 1727 petition mentioned “Wallis’s Bridge” on the road to Pon Pon; see Alexander S. Salley Jr., ed., Journal of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina, November 15, 1726–March 11, 1726/7 (Columbia: South Carolina Historical Commission, 1946), 97; William Williams advertised as administrator of the estate of Thomas Wallis in South Carolina Gazette (hereafter SCG), 13 May 1745, page 2.

[3] A summary of Wallace’s property at this site appears in John Crockatt, John Beswicke, and Alexander Livie to Alexander Rantowle, lease and release for 253 acres in Colleton County, Charleston County Register of Deeds, MM: 237–42; For late-eighteenth-century plats thereof, see Plat Nos. 1284, 1285, 1289, McCrady Plat Collection, Charleston County Register of Deeds Office.

[4] Edwin Breeden, ed., A Guidebook to South Carolina Historical Markers (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2021), 98. The National Register nomination form for the Stono Rebellion site at Wallace’s Tavern is available through the website of the South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

[5] The official report of Lieutenant Governor William Bull specified that the rebellion commenced “at night.” See Smith, Stono, 16.

[6] Part of the Pon Pon Road might have existed before the 1720s, but westernmost part was probably created after the creation of a ferry landing at John Jackson’s plantation. That ferry was authorized by “An Act for removing the ferry now at James Wrixham’s plantation, and establishing the same at Mr. John Jackson’s plantation, across Pon Pon River,” ratified on 9 December 1725; see David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 9 (Columbia: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 64–65.

[7] See Charles F. Philips Jr., Christina Rae Butler, and Sheldon Owens, A History of Battlefield Plantation, MWV Land Sales, Charleston County, South Carolina (Charleston, S.C.: Brockington and Associates, 2014).

[8] William Hutchinson was buried on 18 July 1739; see A. S. Salley Jr., ed., Register of St. Philip’s Parish, Charles Town, South Carolina, 1720–1758 (Charleston, S.C.: Walker, Evans & Gogswell Co., 1904), 259; The will of William Hutchinson “of Charles Town,” dated 13 October 1738, was recorded on 16 October 1739 in South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Will Book 1736–40, page 357; WPA transcript vol. 4, 1738–40, page 177; Ribton Hutchinson advertised for the settlement of his estate in SCG, 4–11 August 1739, page 2. A brief biography of Ribton appears in Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives, volume 2, page 349.

[9] Note that in some plats created in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the western branch of the Stono is described as the middle branch because the development of lands to the west (that is, Caw Caw Swamp) engendered further diminutions of terminology.

[10] J. H. Easterby, ed., The Colonial Records of South Carolina: The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, September 12, 1739–March 26, 1741 (Columbia, S.C.: The Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1952), 158, 230, 233, 236, 283.

[11] In 1712–13, the provincial government authorized the creation of a bridge across the Stono River at or near the plantation of William Stanyarne. This bridge was apparently built, but was gone by 1750, at which time the provincial government authorized the creation of a ferry service “over Stono River, at the place where the bridge stood” (to be paid for by the inhabitants of both St. Paul’s Parish and St. John’s Parish).

[12] Gabriel Laban advertised in the Charleston newspapers of 1733–52 a store at “Stone Landing,” which was occasionally spelled “Stono Landing,” but the location in question was on the Cooper River.

[13] On page 141 of Joseph L. Rivers, comp., Some South Carolina Families, volume 1 (n.p.: by the author, 2005), Joe transcribed the petition of William Godfrey from Brent Holcomb, comp., Petitions for Land from the South Carolina Council Journals, Volume II: 1748–1752 (Columbia, S.C.: SCMAR, 1997), 47, citing the original Council journal pages 494–95.

[14] William Godfrey’s plat, dated 9 December 1749, is recorded in SCDAH, Colonial Plat Books (Copy Series)(S213184), volume 4, page 506. The grant was recorded on 29 November 1750 in SCDAH, Colonial Land Grants [Documents Omitted from Copy Series](S213015), volume 2I (or II), page 122.

[15] SCG, 18 July 1771, page 2: “Lands for sale.” This advertisement ran through October 1st.

[16] The road now called County Line Road was created as a result of “An Act for making a new road between the north and middle branch of Stono River,” ratified on 11 March 1726/7, and transcribed in McCord, Statutes at Large, 9: 65–66.

[17] The earliest advertisement for the partnership of Hutchinson and Grimke appears in South Carolina Gazette, 19–26 October 1734, page 3.

[18] Easterby, Journal of the Commons House, 1739–1741, 63–64.

[19] Note that the historical information provided on the current website of Popular Grove is not accurate.

NEXT: The Mermaid and the Hornet in the Hurricane of 1752

PREVIOUSLY: Careening across the Lowcountry in the Age of Sail

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments