The Star-Spangled Spirit of Charleston

Processing Request

Processing Request

The “Star-Spangled Banner” became our national anthem in 1931, but its history in the Palmetto City goes back much farther. The words were written in Maryland in 1814, while the tune, composed in London during the 1770s, came to South Carolina decades before the War of 1812. This blending of elements old and new was critical to the success of the new patriotic anthem. To understand the spirit in which Charleston audiences received it more than two centuries ago, we have to turn back to the Neo-Classical roots of a once-famous ditty known as “The Anacreontic Song.”

Anacreon was a Greek poet active during the sixth century B.C.E. (that is, about 2,500 years ago). Most of his poems were written for the entertainment of wealthy patrons, and consequently express sentiments that are generally lighthearted and pleasant. He is mostly remembered for copious verses celebrating the virtues and joys of wine, love, and convivial fellowship. This body of work includes numerous references to women, amorous flirtation, and drinking, but the language is never coarse or vulgar. Furthermore, Anacreon specialized in lyric poems that were meant to be sung or declaimed with musical accompaniment. His use of specific meters or rhythmic patterns helped create memorable forms that inspired later writers. Lyric poetry written in imitation of Anacreon, or in the spirit of his works, was described as being “anacreontic.” By its very nature, anacreontic poetry is always associated with music.

Anacreon was a Greek poet active during the sixth century B.C.E. (that is, about 2,500 years ago). Most of his poems were written for the entertainment of wealthy patrons, and consequently express sentiments that are generally lighthearted and pleasant. He is mostly remembered for copious verses celebrating the virtues and joys of wine, love, and convivial fellowship. This body of work includes numerous references to women, amorous flirtation, and drinking, but the language is never coarse or vulgar. Furthermore, Anacreon specialized in lyric poems that were meant to be sung or declaimed with musical accompaniment. His use of specific meters or rhythmic patterns helped create memorable forms that inspired later writers. Lyric poetry written in imitation of Anacreon, or in the spirit of his works, was described as being “anacreontic.” By its very nature, anacreontic poetry is always associated with music.

More than two millennia after the death of Anacreon, the people of eighteenth century Europe witnessed a resurgence of interest in the history and culture of the ancient world. Students of “classical” Greek and Roman literature rediscovered Anacreon along with a host of other writers and drew inspiration from the distant past. As in the contemporary fields of art, architecture, and politics, poets and musicians active during the second half of the eighteenth century created new works inspired by ancient precedents. Much of this new work across many disciplines was created by professional specialists commissioned by wealthy patrons eager to embrace the Neo-Classical spirit of the age. This intersection of professionalism and amateur patronage during the Age of Enlightenment provided the stage for what would later become the national anthem of a yet-unborn country.

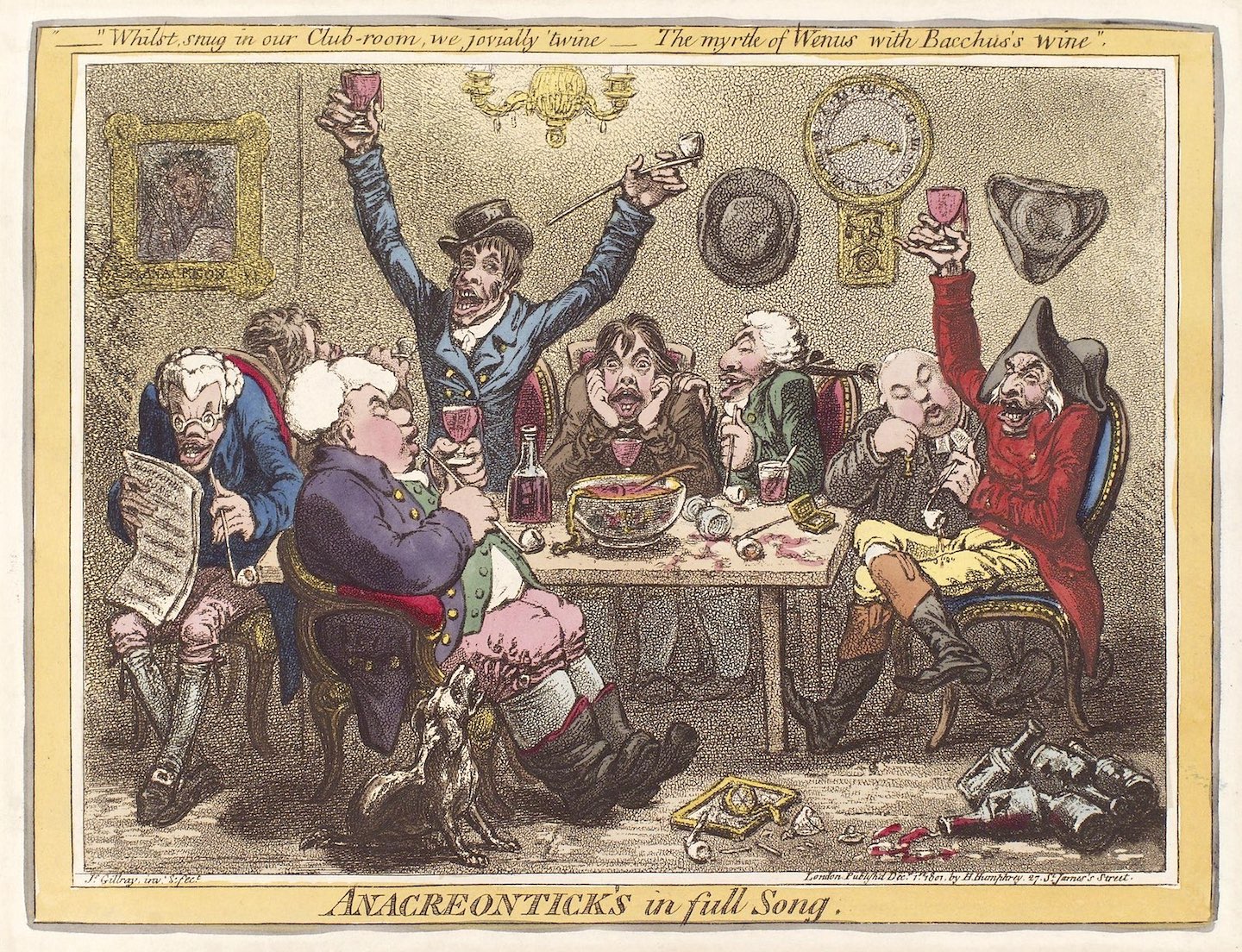

The Anacreontic Society of London, formed around the year 1766, embodied the spirit of the Neo-Classical movement in late-eighteenth-century Britain. The society was composed of affluent gentlemen whose wealth provided ample leisure time to study and appreciate the arts in general. Its members gathered periodically in the metropolis to hear a concert of the latest, most fashionable music, to share a fine meal, and to sing songs reflecting the jovial tradition of old Anacreon. Club members composed new lyric poems extolling the virtues of wine, women, and song, for which professional musicians crafted new tunes to suit the texts. At the conclusion of their concert meetings, the votaries of Anacreon took turns singing solo songs and collaborating in the performance of catches, cannons, and glees—compositions written for two, three, or four voices singing different parts in harmony. These events were lubricated by copious quantities of alcohol, but contemporary accounts assert that the class-conscious members of the Anacreontic Society generally behaved themselves and usually avoided songs containing coarse or vulgar language.

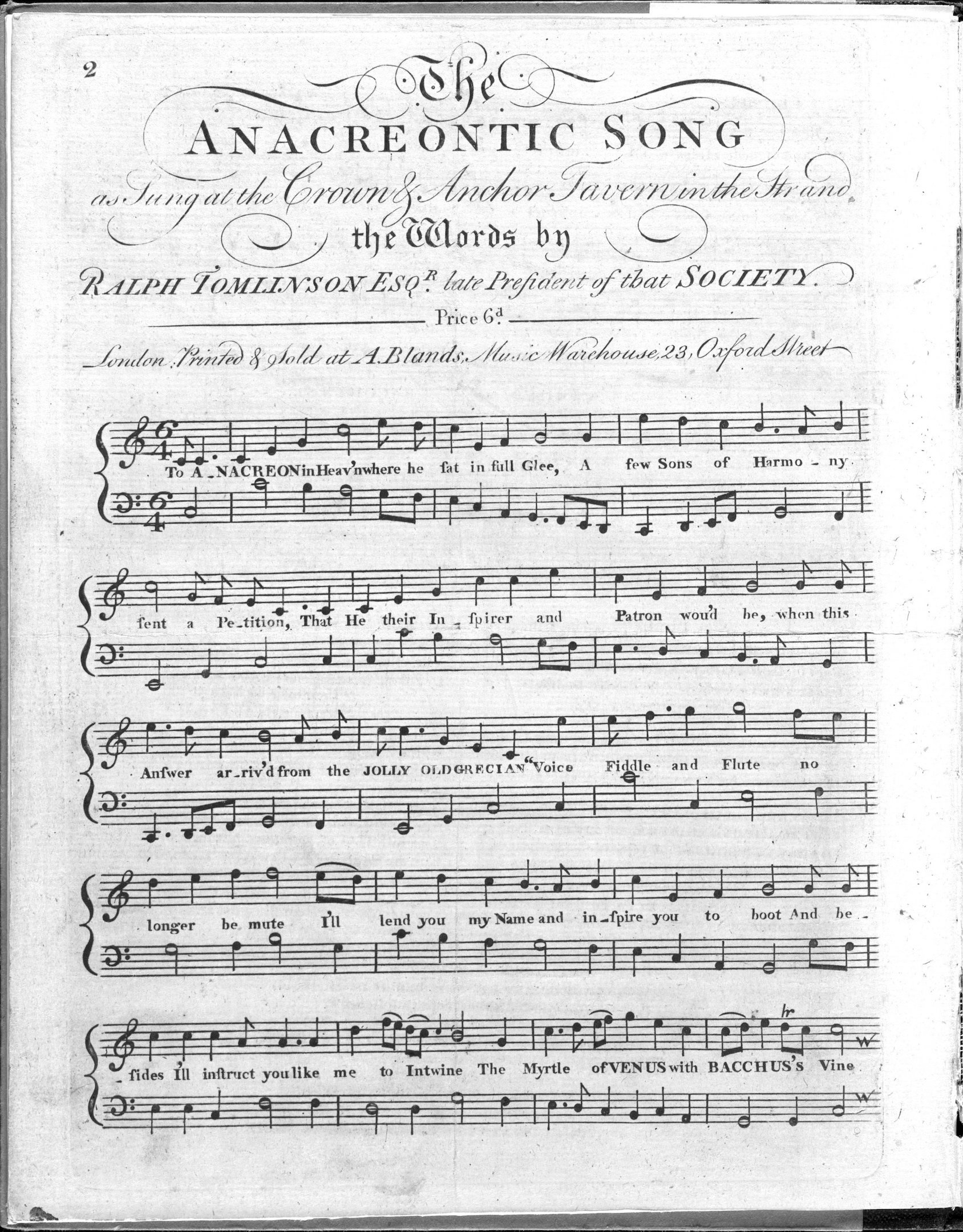

In January of 1775, bachelor attorney Ralph Tomlinson (1744–1778) of London was elected president of the Anacreontic Society. Around that same time, he composed a new poem that addressed the club’s titular figure in a lighthearted appeal. Reflecting the contemporary fascination with Classical culture, Tomlinson’s poem asks Anacreon to inspire a few mortal musicians and their patrons. The ancient Greek poet responds by commanding instruments and voices to sound while he demonstrates his skill in uniting the traditional Roman deities of love and wine. The poem’s first verse illustrates this rhetorical conversation:

In January of 1775, bachelor attorney Ralph Tomlinson (1744–1778) of London was elected president of the Anacreontic Society. Around that same time, he composed a new poem that addressed the club’s titular figure in a lighthearted appeal. Reflecting the contemporary fascination with Classical culture, Tomlinson’s poem asks Anacreon to inspire a few mortal musicians and their patrons. The ancient Greek poet responds by commanding instruments and voices to sound while he demonstrates his skill in uniting the traditional Roman deities of love and wine. The poem’s first verse illustrates this rhetorical conversation:

To Anacreon in heav’n, where he sat in full glee;

A few sons of harmony sent a petition.

That he their inspirer and patron would be;

When this answer arrived from the jolly old Grecian—

Voice fiddle and flute, No longer be mute;

I’ll lend you my name and inspire ye to boot:

And besides I’ll instruct ye, like me, to intwine

The myrtle of Venus with Bacchus’s vine.

Tomlinson handed his new strophic poem to a young professional musician named John Stafford Smith (1750–1836). Smith was an honorary, working member of the Anacreontic Society who composed the music for several prize-winning songs in the mid-1770s. At some point during the winter of 1775–76, the pair presented their new anacreontic song to the society. It was originally performed as a solo piece, but fellow club members joined voices for the final, repeating line of each verse. “To Anacreon in Heaven” quickly became a favorite among members of the society, which was expanded in the autumn of 1776 to accommodate a surge of new members. The joint effort of Ralph Tomlinson and John Stafford Smith thereafter became the “constitutional song” of the Anacreontic Society, performed at the beginning of the singing portion of their regular meetings.

The words of “To Anacreon in Heaven” were first published in the late 1770s, and printed versions of both text and tune appeared in the early 1780s. After the peaceful conclusion of the American Revolution in 1783, gentlemen amateurs on both sides of the Atlantic embraced the musical model of the Anacreontic Society of London and formed scores of similar organizations. London booksellers responded to this phenomenon by publishing hundreds of anacreontic vocal works in dozens of printed collections during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. One of the several collections published by John Stafford Smith, for example, included a more sophisticated arrangement of “To Anacreon in Heaven” for three men’s voices singing in harmony. The solo version with a choral refrain remained so popular, however, that it was frequently described in print simply as “The Anacreontic Song.”[1]

The words of “To Anacreon in Heaven” were first published in the late 1770s, and printed versions of both text and tune appeared in the early 1780s. After the peaceful conclusion of the American Revolution in 1783, gentlemen amateurs on both sides of the Atlantic embraced the musical model of the Anacreontic Society of London and formed scores of similar organizations. London booksellers responded to this phenomenon by publishing hundreds of anacreontic vocal works in dozens of printed collections during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. One of the several collections published by John Stafford Smith, for example, included a more sophisticated arrangement of “To Anacreon in Heaven” for three men’s voices singing in harmony. The solo version with a choral refrain remained so popular, however, that it was frequently described in print simply as “The Anacreontic Song.”[1]

Although the Anacreontic Society of London dissolved sometime around the year 1793, the cultural movement it inspired continued to thrive in Britain and abroad. Charleston, like other cities in the young United States of America, hosted a number of gentlemen’s clubs that met periodically for convivial entertainment that occasionally included singing. The Palmetto City was at that time already one of the most musical communities in North America. The backbone of the city’s musical life was the St. Cecilia Society, a private organization that hosted an annual concert series between 1766 and 1820. That organization was run by local gentlemen who hired an orchestra and invited their friends and families to attend concerts of vocal and instrumental music performed by gentlemen amateurs and professional musicians. The presence of ladies, young and old, tempered the decorum of the St. Cecilia concerts, however. The gentlemen organizing those events felt that convivial repertoire like “The Anacreontic Song” was better suited to gatherings at which their wives and daughters were not present.[2]

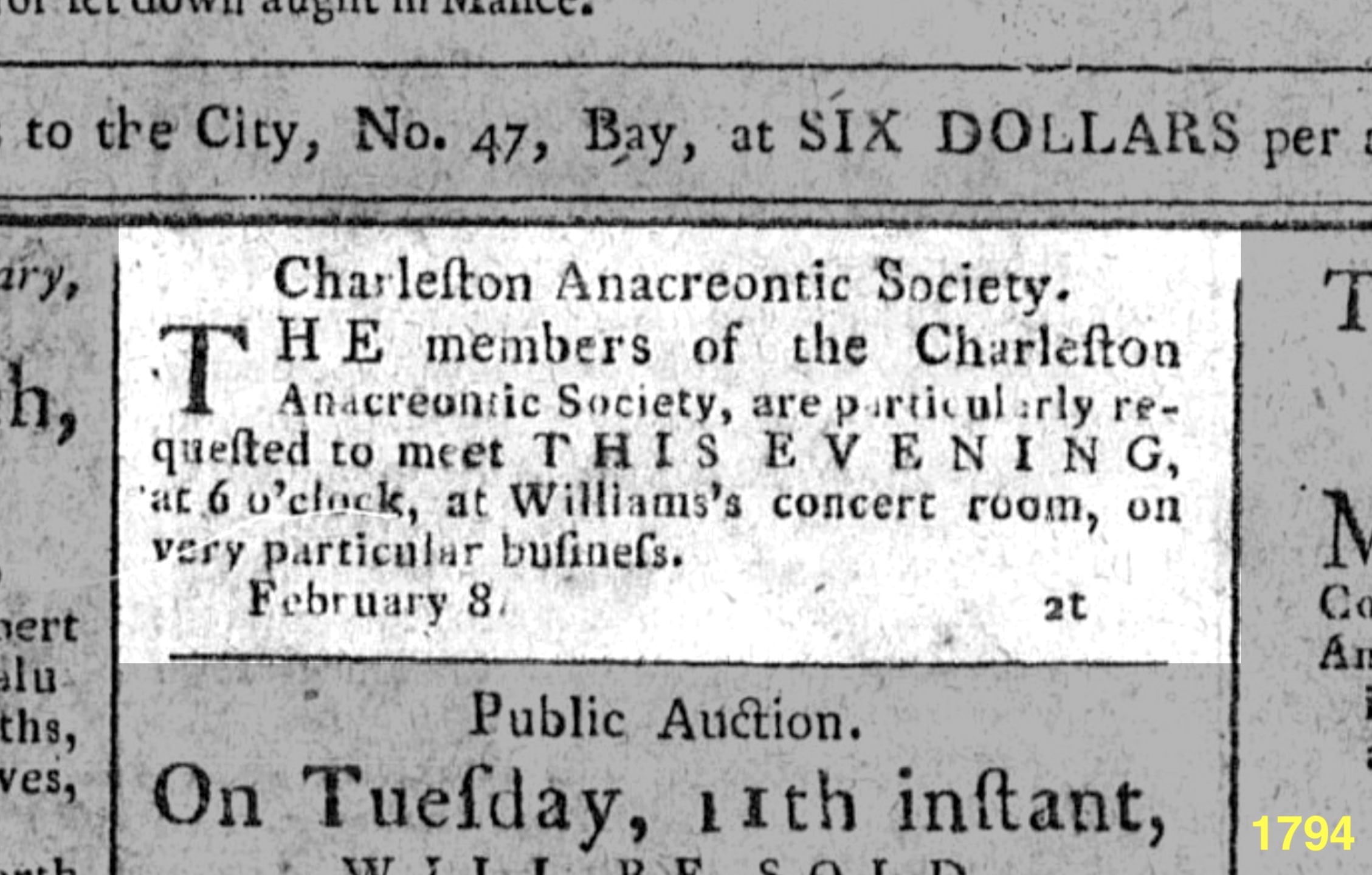

Charleston had its own Anacreontic club in the early 1790s, but the precise dates of its formation and demise are unknown. Like a myriad of other gentlemen’s clubs of that era, the Charleston Anacreontic Society was a private organization that held regular meetings in a familiar venue and conducted its affairs outside of the public eye. We know the local votaries of Anacreon were active during the early months of 1794 only because they published a few meeting notices in the local newspapers during that era. From the distance of more than two centuries, it’s now impossible to know when this club was organized, how long it flourished, or the identity of its members.

On the other hand, the sparse text of their newspaper notices does reveal a bit of information about this club’s musical purpose. In 1794 at least, the Charleston Anacreontic Society met at the “concert room” of John Williams’s coffee house, also known as the Carolina Coffee House, then located at the northwest corner of Tradd Street and Bedon’s Alley. There the gentlemen amateurs forming the club gathered to share a meal and imbibe their favorite beverages. Perhaps accompanied by local professional musicians, as in London, the members performed vocal catches and glees drawn from the dozens of published collections available at local bookshops. There was no audience; the members sang and harmonized for their own entertainment and to enhance the pleasure of fraternal company. Although there are no extant records to prove they sang “To Anacreon in Heaven” on Tradd Street in the early 1790s, it seems reasonable to conclude that the Charleston Anacreontic Society would have embraced the “constitutional song” of their London model.[3]

Anyone perusing the newspapers printed in Charleston and other American cities during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries can find dozens of anacreontic poems celebrating wine, women and music, written by gentlemen amateurs in the style of Anacreon’s famous verses. To this body of material we can add the work of Irish poet Thomas Moore (1779–1852), who in 1800 published a collection of Romanticized English translations of Anacreon’s Greek poems. Moore’s translations became so popular on both sides of the Atlantic that newspapers, including those in Charleston, dubbed him “Anacreon Moore.” Published without music settings, however, Moore’s work did not diminish the continued popularity of John Stafford Smith’s musical setting of “To Anacreon In Heaven,” which continued to be held in widespread public esteem as “The Anacreontic Song.”

Anyone perusing the newspapers printed in Charleston and other American cities during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries can find dozens of anacreontic poems celebrating wine, women and music, written by gentlemen amateurs in the style of Anacreon’s famous verses. To this body of material we can add the work of Irish poet Thomas Moore (1779–1852), who in 1800 published a collection of Romanticized English translations of Anacreon’s Greek poems. Moore’s translations became so popular on both sides of the Atlantic that newspapers, including those in Charleston, dubbed him “Anacreon Moore.” Published without music settings, however, Moore’s work did not diminish the continued popularity of John Stafford Smith’s musical setting of “To Anacreon In Heaven,” which continued to be held in widespread public esteem as “The Anacreontic Song.”

The stately cadence of Smith’s famous tune provided a familiar framework for many new poems written for patriotic occasions. In the decades after the American Revolution, for example, it was used to accompany new texts celebrating George Washington, John Adams, the Marquis de Lafayette, “Our Country’s Efficiency,” “Columbia Victorious,” the Erie Canal, and dozens of other topics. When Captain Stephen Decatur Jr. of the U. S. Navy returned home in 1805, after fighting along the shores of Tripoli during the First Barbary War, a young lawyer in Maryland named Francis Scott Key (1779–1843) used “The Anacreontic Song” as the model for a new lyric poem titled “When the warrior returns from the battle afar.” Nine years later, Key borrowed the same scaffolding for his most famous work.[4]

On the night of September 13th, 1814, Francis Scott Key watched as the British Navy began shelling Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor. That bombardment, which occurred during the second great war between the United States and Great Britain, commonly called the War of 1812, continued into the morning hours of September 14th. At dawn, Key was overjoyed to see our national flag, spangled with fifteen stars and fifteen stripes, still flying over the defiant ramparts of Fort McHenry. That morning he scribbled descriptive notes on scraps of paper and expanded them into a formal poem later at home. His strophic verses, initially titled the “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” were soon published in a local newspaper and sung to the tune of “The Anacreontic Song” before audiences at local theaters. Within a few months, Key’s verse was circulating throughout the United States under the more familiar title of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The War of 1812 concluded in early 1815 with an American victory that triggered a wave of patriotic enthusiasm. In celebrations across the young nation, including those here in Charleston, “The Star-Spangled Banner” was recited, sung, and applauded by audiences well-familiar with “The Anacreontic Song” of the previous generation. Ralph Tomlinson’s jovial words were supplanted by those of Francis Scott Key, of course, but John Stafford Smith’s English tune, with a few modifications, gained new life as an American classic. In the succeeding decades, thousands of band musicians across the nation—including performers both Black and White—sustained the famous tune through each rising generation.[5]

The War of 1812 concluded in early 1815 with an American victory that triggered a wave of patriotic enthusiasm. In celebrations across the young nation, including those here in Charleston, “The Star-Spangled Banner” was recited, sung, and applauded by audiences well-familiar with “The Anacreontic Song” of the previous generation. Ralph Tomlinson’s jovial words were supplanted by those of Francis Scott Key, of course, but John Stafford Smith’s English tune, with a few modifications, gained new life as an American classic. In the succeeding decades, thousands of band musicians across the nation—including performers both Black and White—sustained the famous tune through each rising generation.[5]

“The Star-Spangled Banner” became a regular feature of patriotic celebrations after the peace of 1815, but it did not immediately gain a position of preference. It was performed alongside other popular songs on festive occasions until the nation began to the feel the need to designate a definitive, unifying anthem. In the years after the divisive Civil War, “the Star-Spangled Banner” slowly emerged as the national favorite. The United States Navy officially adopted it in 1893, and in 1917 it became the official anthem of all American forces headed to join the Great War then raging in Europe. After a number of unsuccessful efforts, the United States Congress official designated “The Star Spangled Banner” our national anthem at the end of 1931.[6]

The purpose of this quick tour through the long history of our national anthem was to establish the necessary background for a few simple points related to this patriotic season. While the words of “The Star-Spangled Banner” were written in Maryland in 1814, the tune, composed in London in the 1770s, was familiar to local audiences who had followed English musical fashions since colonial times. In a new era of independence more than two hundred years ago, the people of Charleston embraced this new anthem because it harmonized with the spirt of the old city by the sea. Its well-known tune was molded by the same Neo-Classical ideas that informed the political thought behind the American Revolution, while the lyric verse celebrates the resilience that empowers the people of Charleston and this nation to persevere in the face of adversity. Our national anthem is more than just a stately old hymn about a specific military victory; it’s a time capsule that echoes the complexity of the American experience.

[1] Oscar George Theodore Sonneck, “The Star-Spangled Banner” (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1914), available online in Google Books; William Lichtenwanger, The Music of the “Star-Spangled Banner”: From Ludgate Hill to Capitol Hill (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1977), available from the website of the Library of Congress.

[2] For a discussion of the society’s concerts, venues, repertoire, and performers, see Nicholas Michael Butler, Votaries of Apollo: The St. Cecilia Society and Concert Patronage in Charleston, South Carolina, 1766–1820 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007).

[3] [Charleston, S.C.] City Gazette, 1 February 1794, page 3: “A meeting of the Charleston Anacreontic Society, will be held THIS EVENING, at Williams’s coffee house, where the members are requested to attend. Catches and glees to commence at half past 6 o’clock”; City Gazette, 8 February 1794, page 1: “The members of the Charleston Anacreontic Society, are particularly requested to meet THIS EVENING, at 6 o’clock, at Williams concert room, on very particular business.” Note, also, that an actor named Mr. Chambers sang “The Anacreontic Society” at the Charleston Theatre on Broad Street on 27 June 1794, and this theatrical practice was repeated many times in subsequent years; see South Carolina State Gazette, 27 June 1794, page 3.

[4] The text of Thomas Paine’s “patriotic song” titled “Adams and Liberty, set to “Anacreon in Heaven,” appeared in the Charleston City Gazette, 27 June 1798, page 3; “Our Country’s Efficiency” appeared in Charleston Evening Courier, 17 August 1798, page 3; a version of “Anacreon in Heaven” dedicated to George Washington appeared in City Gazette, 25 February 1798, page 2; “Columbia Victorious” appeared in City Gazette, 30 December 1812, page 2; a version for the “Erie Canal” appeared in Charleston Courier, 9 November 1824, page 1; and a Lafayette version appeared in Courier, 14 March 1825, page 2. Richard Hill, “Music of the Star Spangled Banner in the United States before 1820,” in Essays Honoring Lawrence C. Wroth (Portland, Me.: Anthoensen Press, 1951), identified sixty-seven texts set to “Anacreon in Heaven” before the Battle of Baltimore in September 1814. Lichtenwanger, Star-Spangled Banner, endnotes 82 and 83, describes Key’s 1805 poem.

[5] For example, patriotic references to the “Star-Spangled Banner” appear in City Gazette, 28 February 1815, page 2; City Gazette, 26 October 1815, page 2.

[6] George J. Svejda, History of The Star Spangled Banner from 1814 to the Present (Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior, February 28, 1969).

NEXT: South Carolina’s First Public Lending Library in 1698

PREVIOUSLY: The Moving Memorials to Elizabeth Jackson

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments