Squeezing Charleston Neck, from 1783 to the Present

Processing Request

Processing Request

Over the past three centuries, the definition of Charleston Neck, a geographic feature I introduced in last week’s episode, has changed radically. It once encompassed the entire tongue of land between the rivers Ashley and Cooper, but the steady growth of urban development on the peninsula gradually whittled it down to a handful of neighborhoods that were finally swallowed by annexation in the late twentieth century. Today, we’ll complete our chronological tour of Neck geography and consider how the identity of this once blighted area is about to be reborn as the final frontier on the Charleston peninsula.

Definition Three (continued from last week): The Neck above Boundary Street

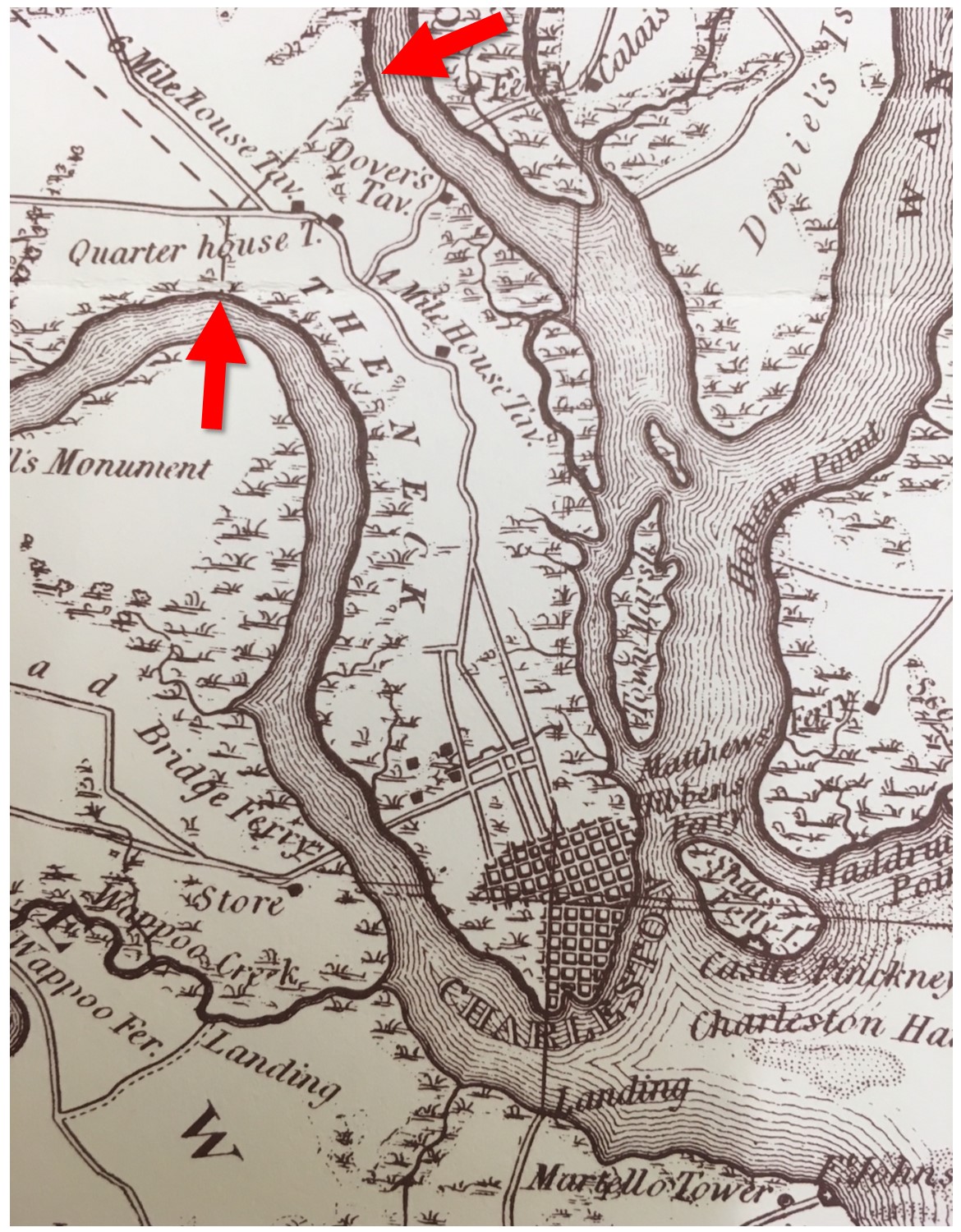

The municipal charter incorporating the City of Charleston, ratified by the South Carolina General Assembly in August 1783, described the physical limits of the city in rather simple terms. The city encompassed a roughly triangular portion of the peninsula bounded on the southwest by the Ashley River, on the southeast by the Cooper River, and on the north by the north side of Boundary Street (now called Calhoun Street). The state’s 1783 charter also conveyed to the City of Charleston “the lands on which the horn-work [a tabby fortress], at the north part of the city, is situate, and the public lands near the same,” which the provincial government had purchased from the Wragg and Manigault families in 1758 to defend the entrance to the town. That additional area, comprising fourteen acres on the north side of Boundary Street, but south of Hutson and Vanderhorst Streets, stretched from St. Philip Street on the west to Meeting Street on the east.[1] It eventually included a public cemetery, the Charleston Orphan House, Marion Square, and the Citadel, all of which were built on land that was technically within the limits of the City of Charleston. Everything else north of Boundary (Calhoun Street), stretching approximately six miles to the northern limits of the parish of St. Philip, was simply called the Neck.

In the late eighteenth century, this large Neck area included numerous small farms, a few larger plantations, pastures, and a small number of suburban residences. Owing to the British invasion of Charleston Neck in the spring of 1780, and the subsequent siege of the town, however, the Neck’s southern half—from Boundary (Calhoun) street to the area around what is now Mount Pleasant Street and Sans Souci Street—was a battle-scarred landscape in need of repair. The decades immediately after American Revolution saw the rise of new farms, houses, and shops, as well as the creation of some new suburban boroughs, including Wraggborough, Mazyckborough, Radcliffeborough, Elliottborough, Cannonborough, as well as the villages of Washington, Islington, New Market, Rumney, and Hampstead (which was established in 1769 but destroyed during the war). The people residing and working on the Neck were primed for recovery, but they felt limited by the fact that there was only one road bisecting the entire neck of land between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers—the so-called “broad path” or the “high road” leading out of Charleston (the northward extension of King Street).

In February 1785, “sundry owners of land on Charleston Neck” petitioned the General Assembly for the creation of “other roads to run nearly parallel to each river or in a straight line to the Quarter House” (near present Cosgrove Avenue).[2] Such new roads would have to traverse numerous private properties along the Neck, however, so a number of property owners voiced their objection to the plan in a counter-petition. In March 1785, the legislature settled on a compromise plan that created two new roads through just the southern part of the Neck. The state directed the Commissioners of Roads for the parishes of St. Philip and St. Michael (a body created in 1721) to create one new road starting from the center of the Harleston neighborhood, on the west side of the peninsula, and continuing northward in a straight line until it intersected with Congress Street in the newly-created village of Washington. Originally called Pinckney Street, this new road has been known as the northern part of Rutledge Avenue since 1850.

More importantly, in March 1785 the state also empowered the local road commissioners to extend Meeting street northward from Boundary (Calhoun) Street in a straight line, seventy feet wide, to a point on the Neck where it intersected with the “high road” (that is, what we now call upper King Street).[3] If you look at a map of Charleston, you’ll notice that Meeting Street is in fact a perfectly straight, broad line from Calhoun Street to a point just south of Cunnington Avenue, which you’ll recognize as the street that leads to the entrance of Magnolia Cemetery. That landmark is important because it helps us to understand a complaint made about this project in 1789, which stated that the survey work “to extend Meeting Street to Mr. William Cunnington’s gate on Charleston Neck” was done in the month of December 1785.[4]

From 1786 to the mid-1920s, King Street and Meeting Street merged into one path at a point commonly called “the cross roads,” located just north of Mount Pleasant Street. From that point, the northward continuation of the main road in and out of Charleston—the old “broad path” or “high way”—became known as Meeting Street Road. Prior to 1785, the main road leading from the countryside into Charleston led to King Street, and so King Street became the town’s shopping district or “high street.” With the extension of Meeting Street to the “cross roads” in late 1785, however, the state initiated a new tradition of entering the city via Meeting Street that endures to this day.

From 1786 to the mid-1920s, King Street and Meeting Street merged into one path at a point commonly called “the cross roads,” located just north of Mount Pleasant Street. From that point, the northward continuation of the main road in and out of Charleston—the old “broad path” or “high way”—became known as Meeting Street Road. Prior to 1785, the main road leading from the countryside into Charleston led to King Street, and so King Street became the town’s shopping district or “high street.” With the extension of Meeting Street to the “cross roads” in late 1785, however, the state initiated a new tradition of entering the city via Meeting Street that endures to this day.

In the decades after the incorporation of Charleston in 1783, the city prospered, its population grew, and its housing stock became more crowded. To avoid paying high rents and higher municipal taxes, some people preferred to reside out of town, in the less populated Neck area north of Boundary Street, where property was cheaper and there were fewer taxes to pay. Other folks preferred to reside on the Neck because there was no police presence north of Boundary Street besides the obligatory militia patrol system (more about that topic in a future episode), and the rule of law was not strictly enforced. By the turn of the nineteenth century, both the citizens of urban Charleston and the residents of the suburban Neck were growing increasingly frustrated with the disparities between their two communities. The majority of the voting populous demanded changes, and the state legislature responded by creating a sort of quasi-government for the Neck—a body called the Commissioners of Cross Roads.

The board of “Commissioners of Cross Roads for Charleston Neck” was a civic body created by a state law in December 1811 to provide a very rudimentary form of government for the unincorporated portion of Charleston Neck between Boundary Street and the northern limits of the parish of St. Philip. The name of this board was not derived from “the cross roads” created in 1785 by the junction of King Street and Meeting Street Road that I mentioned earlier. Rather, the Commissioners of Cross Roads were derived from the old Commissioners of Roads, a body created in 1721. The state act of 1811 divided the traditional road commissioners into two groups: one board to administer the “high” or main roads traversing the length of the parishes of St. Philip and St. Michael, and a new board to administer the other roads and streets that crossed the main roads, as well as other civic needs in the parish of St. Philip, north of the City of Charleston. Sound ridiculous? Yes.

The first board of Commissioners of Cross Roads was elected in October 1812, at which time they commenced an enduring habit of meeting at least once a month to transact public business. Over the years, as the population and commerce of the Neck increased, many Neck residents felt the need for a stronger government in their community. In response to a stream of citizen’s petitions, the state legislature gradually expanded the powers of the Commissioners of Cross Roads in a series of statutes ratified between 1818 and 1848. By the end of the 1840s, the Neck commissioners were, for all practical purposes, a highly-functioning municipal government administering a large unincorporated area. Hardly anyone today remembers the Commissioners of Cross Roads for Charleston Neck, but that board was a significant force on the Neck during the first half of the nineteenth century. We’ll delve deeper into their story in a future episode, but for the moment, let’s get back to our overview of the geography of the Neck.

Definition Four: The Neck above Mount Pleasant Street

Throughout the 1840s, Charleston’s City Council began dropping not-so-subtle hints that it might like to annex part of the Neck into its jurisdiction, as a means of extending more robust police control over the rowdy unincorporated area north of Boundary Street. The vast majority of the voters on the Neck, as well as the Commissioners of Cross Roads, steadfastly objected to these overtures, but the majority of the state legislature in Columbia sided with the City Council of Charleston. In December 1849, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified an act empowering City Council to annex part of the Neck. More specifically, the state empowered the city to annex “all that part of St. Philip’s Parish, lying between the present limits of the city [that is, Boundary Street], and a line to be drawn due west from Cooper River to Ashley River, by the junction of Meeting and King street.”[5] That vague description of the new boundary wasn’t meant to be legally binding—it was merely a suggested starting point. The state act of December 1849 directed a group of local commissioners to determine the exact placement of the new boundary between the Neck and the city. After a series of meetings and surveys in June of 1850, the commissioners defined the new boundary as a line running down the center of Mount Pleasant Street and continuing west and east to the Ashley and Cooper Rivers respectively.[6] At a series of City Council meetings in October 1850, the city also changed several street names on the Neck to avoid duplication with older streets south of the former boundary. Boundary Street, for example, officially became Calhoun Street on the 19th of October, 1850.[7]

Following the city’s annexation of a large part of the Neck in 1850, the legally-defined geographic scope of the Neck was reduced to the land north of Mount Pleasant Street and south of the boundary of St. Philip’s Parish (around modern Cosgrove Avenue). The Commissioners of Cross Roads for Charleston Neck continued to exercise jurisdiction over this area, but that situation did not last much longer. The new state constitution of 1868 adopted a new system of county electoral districts in place of the traditional parish system. At that point, the Commissioners of Cross Roads, a vestige of antebellum attempts to govern the unincorporated area of the parish of St. Philip, was replaced by a board of county commissioners.

At the end of the American Civil War, the Neck above Mount Pleasant Street was still a quaint, thinly populated, agrarian landscape. That traditional character changed dramatically right after the war, however, with the advent of large scale phosphate mining operations in the Charleston area. From the late 1860s to the late 1890s, residents of the Neck witnessed the construction of numerous phosphate processing plants and associated industrial railroad service lines. At these plants located between the waters of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, the soft phosphate rocks were washed, pulverized, and treated with sulfuric acid to break them down into a valuable, powdery fertilizer. As the local fortunes of this toxic industry declined at the turn of the twentieth century, the plants were abandoned. The cleanup of the disused phosphate properties, contaminated by years of industrial waste, would have to wait for future generations.[8]

Contemporary with the decline of the phosphate industry was the creation of the Charleston Naval Base in 1901. The arrival of the military brought new development, new jobs, and new residents to the Charleston Neck, but technically the expansive base on the Cooper River straddled the traditional boundary line between the parishes of St. Philip and St. James, Goose Creek. Although much of the facilities and personnel spread north of the Neck, into what we now think of as North Charleston, the Naval Base also spurred the construction of new support facilities, satellite industries (such as coal and oil depots), as well as modest homes in the traditional Neck boundaries between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. By the time of World War I, the former pastures and farmland of the Neck were nearly extinct. It was now a mixed-use, jumbled landscape with only one main road and no modern services. Something had to change.

The spirit of progress bloomed on the Neck in the 1920s. The rapid rise of the automobiles and trucks, combined with the creation of the state highway department in 1917, led to increased local attention to the dismal state of the solitary road—Meeting Street Road—conducting traffic across the Neck between the booming Naval Base and the busy city of Charleston. In the mid-1920s, the state began constructing a modern concrete extension of King Street northward from the Charleston city limits. At a point called “Five Mile,” the former location of the Neck’s five-mile stone, the highway department built a viaduct or overpass, allowing the new “King Street Extension” to fly over the railroad and the path of Meeting Street Road. After three years of planning and construction, the King Street Extension opened on April 15th, 1926.[9] If you’ve ever driven on this road, you probably felt underwhelmed at the quality of the road and the adjacent scenery, but the King Street Extension project was a big deal in its day. It was considered a vastly improved and more attractive thoroughfare leading into the city than the old route, which had followed a path adopted by the earliest settlers in the late 1600s.

The construction of a major new road through the Neck in the mid-1920s was intended to facilitate a greater volume of automobile traffic, which in turn would make it easier for more people to reside on the Neck and drive to Charleston to spend their money. But there were no modern utilities available on the Neck to attract new suburbanites. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, the City of Charleston began providing running water, sewerage, and electricity to its constituents, but the unincorporated Neck had no such services. To overcome this shortcoming, the state legislature in 1928 created the “St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s Fire and Water Commission,” which in 1935 was renamed the “St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s Sewer District,” which in 1936 was again renamed the “St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s Public Service District.” The jurisdiction of this public utility service was confined to the unincorporated area of the Neck within the ancient boundary of the parish of St. Philip (that is, the land southeast of Cosgrove Avenue), and it should not be confused with the “North Charleston Water, Fire, Sewer, and Lighting District,” which the state created in 1936 to provide services to the unincorporated area around the northwest side of the U.S. Naval Base. That public entity, by the way, became the “North Charleston Public Service District” in 1939, and in 1957 it merged with the “St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s Public Service District” to create the “North Charleston Consolidated Public Service District.”

These details about the arrival and jurisdiction of public services might seem pedantically peripheral in a conversation about the geography of the Neck, but they set the stage for the last major transformation of the Neck’s identity. All of the peninsular real estate north of the City of Charleston underwent a massive transformation between the 1860s and the 1960s, changing from a patchwork of sparsely populated farms to a highly industrialized landscape with a growing suburban population. The completion of the last segment of Interstate Highway 26, between Cosgrove Avenue and downtown Charleston, in the spring of 1968 promised to bring even more development to the area. The remnants of the Neck, and the bustling suburban area around on the northwestern side of the Naval Base, remained unincorporated, however, without any real sense of leadership or identity. Within this civic vacuum, a core group of people initiated a struggle to gain incorporation for a new municipal entity. After several unsuccessful bids, the City of North Charleston was finally incorporated in 1972, with a southern border initially confined to the bounds of the old Naval Base. Suddenly, the Neck became a conspicuous desert of sorts—an unincorporated no man’s land sandwiched between two municipal bodies hungry for additional tax revenue. From that moment, the extinction of the Neck became an inevitable scenario.

These details about the arrival and jurisdiction of public services might seem pedantically peripheral in a conversation about the geography of the Neck, but they set the stage for the last major transformation of the Neck’s identity. All of the peninsular real estate north of the City of Charleston underwent a massive transformation between the 1860s and the 1960s, changing from a patchwork of sparsely populated farms to a highly industrialized landscape with a growing suburban population. The completion of the last segment of Interstate Highway 26, between Cosgrove Avenue and downtown Charleston, in the spring of 1968 promised to bring even more development to the area. The remnants of the Neck, and the bustling suburban area around on the northwestern side of the Naval Base, remained unincorporated, however, without any real sense of leadership or identity. Within this civic vacuum, a core group of people initiated a struggle to gain incorporation for a new municipal entity. After several unsuccessful bids, the City of North Charleston was finally incorporated in 1972, with a southern border initially confined to the bounds of the old Naval Base. Suddenly, the Neck became a conspicuous desert of sorts—an unincorporated no man’s land sandwiched between two municipal bodies hungry for additional tax revenue. From that moment, the extinction of the Neck became an inevitable scenario.

Definition Five: The Neck as a Vestigial Marker

The City of Charleston first expanded beyond the peninsula in 1960, when it began annexing the rapidly growing suburban neighborhoods west of the Ashley River. City Council might have entertained ideas about annexing the Neck during that era, but the Neck’s industrial character and its modest tax base made it significantly less attractive than the valuable prospects on the opposite shore. Following the incorporation of the City of North Charleston in 1972, however, Charleston’s City Council realized that its new northern neighbor might soon lay claim to the nearly four-mile stretch of Neck that could be valuable at some future date. Over the next several years, the two cities began competing for the attention of Neck voters in a race to annex the remaining vestiges of the unincorporated land between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers.

As the City of North Charleston rapidly annexed the neighborhoods immediately south of the Naval Base in 1972–74, the City of Charleston aggressively courted voters on the southern end of the Neck, immediately north of Mount Pleasant Street. In a referendum held in November 1976, a majority of voters from several Neck neighborhoods—including Rosemont, Silver Hill, and Hibernian Heights—expressed a desire to join the City of Charleston.[10] The voters of Union Heights voted against annexation by the City of Charleston in 1976, and in subsequent years they continued to resist overtures from both the north and the south. Finally, in February 1996, the City of North Charleston entered into a contract with the old North Charleston Public Service District for the city to take over most services provided to residents in the unincorporated remnants of the Neck. The contract went into effect on 1 April 1996 and expired on 30 June 1997.[11] At the expiration of that contract, the City of North Charleston annexed the neighborhood of Union Heights, the last remaining parcel of unincorporated real estate on the Neck.

Let’s take a minute to review the historic definitions of Charleston Neck:

First, in the 1670s and beyond, early European settlers described the entire peninsula as a “neck of land” between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers.

Second, following the establishment of “new Charles Town” in 1680, everything north of the town boundary (Beaufain/Hasell Streets) to the northern limit of the parish of St. Philip was called “Charles Town Neck.”

Third, the creation of Boundary (Calhoun) Street in 1769–1770 marked a new, unofficial boundary between the Charles Town and the Neck, and it became the official line of demarcation on the incorporation of the city in 1783.

Fourth, the City of Charleston’s 1850 annexation campaign reduced the definition of the Neck to encompass all of the land between Mount Pleasant Street and the northern boundary of St. Philip’s Parish.

Fifth, the remaining portions of the unincorporated Neck were annexed by the city governments of Charleston and North Charleston between 1972 and 1997.

In some respects, I’m tempted to say “the Neck” no longer exists. That is, the traditional definition of the unincorporated, rural Neck is now extinct. On the other hand, one might argue that the definition of “the Neck” has come full circle, and that our current use of that phrase harkens back to the meaning intended by the first European colonists who settled in this area. Looking at the Lowcountry landscape with fresh eyes in the 1670s, they saw a vacant, undifferentiated land mass between the rivers they called Ashley and Cooper, a neck of land full of potential and promise. Over three centuries, we carved up the land and made artificial distinctions between town and country, city and suburb. The corporate arms of municipal government have now fully embraced the Neck, however, and the entire neck of land between the Ashely and Cooper Rivers is again a (relatively) undifferentiated corporate body. It took our community three hundred years to do it, but we have at last swallowed the Neck.

The traditional definition of Charleston Neck might be a thing of the past, but the economic and cultural life of the Neck is poised for a potentially dramatic rebirth in the coming years. The city governments of both Charleston and North Charleston, as well as the Berkeley-Charleston-Dorchester Council of Governments, are busy working with residents and developers to plan ways to improve the Neck in more sustainable manner than was done in the past. At the risk of sounding like an Internet cliché, we’re talking about Neck 2.0 (or perhaps Neck 5.0). Whatever you call it, the Neck is the last frontier of development on the peninsula, and its transformation in the coming years is destined to be headline news. As a citizen, I urge everyone to get informed and involved. As a historian, I hope that this brief tour of three centuries of history has helped you get a grip on this slippery subject.

[1] The city enlarged its footprint north of Boundary in 1789 by purchasing a narrow strip of land between Meeting and King Streets for a tobacco inspection station, which later became the site of the Citadel. The state legislature confirmed the inclusion of this property, bounded to the north by Hutson Street, within the limits of the city by acts ratified in 1789 and 1822. See Act No. 1456, “An Act for regulating the Inspection and Exportation of Tobacco; and for other purposes herein mentioned,” ratified on 13 March 1789, in Thomas Cooper, comp., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, Vol. 5 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1839), 113–21; and Act No. 2297, “An Act to define the Boundary line between the City of Charleston and Charleston Neck; and for other purposes therein mentioned,” ratified on 21 December 1822, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 6 (Columbia: A. S. Johnston, 1839), 193–94.

[2] South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Petitions to the General Assembly, 1785, No. 81 and No. 88.

[3] See Act No. 1282: “An Act for keeping in repair the several High-Roads and Bridges throughout this State, and for laying out the several new Roads and Ferries therein mentioned,” ratified on 24 March 1785, in David J. McCord, ed., Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 9 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1841), pp. 298–99 of 292–301.

[4] SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, 1789, No. 81.

[5] Act No. 3076: “An Act to extend the Limits of the City of Charleston,” ratified on 19 December 1849, in Acts of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Passed in December, 1849 (Columbia, S.C.: I. C. Morgan, 1849), 579–80.

[6] See the proceedings of the City Council meeting of 16 July 1850, printed in Charleston Courier, 18 July 1850.

[7] See the proceedings of the City Council meeting of 19 October 1850, printed in Charleston Courier, 21 October 1850.

[8] For more information on the phosphate industry, see Shepherd W. McKinley, Stinking Stones and Rocks of Gold: Phosphate Fertilizer and Industrialization in Postbellum South Carolina (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2014).

[9] See Charleston News and Courier, 16 April 1926, page 1.

[10] There were legal challenges to the validity of the referendum result, but the City of Charleston prevailed and began providing public service to the newly-annexed neighborhoods in late July 1977. See Charleston News and Courier, 21 November 1976, page 8; and Charleston Evening Post, 25 July 1977.

[11] Charleston Post and Courier, 23 February 1996, page 2B: “North Charleston expands its public service.”

PREVIOUS: Grasping the Neck: The Origins of Charleston’s Northern Neighbor

NEXT: Murder at Four Holes Swamp in 1744

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments