A Short History of Philadelphia Alley

Processing Request

Processing Request

Philadelphia Alley is not the shortest or narrowest thoroughfare in the city of Charleston, but it is sufficiently small to escape the attention of many residents and tourists. For those who have stumbled into its entrances on Queen and Cumberland Streets in the past, they have discovered a picturesque yet historically mute piece of Charleston. The facts behind the creation and early existence of Philadelphia Alley have been forgotten by the living, only to be replaced by rumors and fabrication. Its proximity to the city’s historic Market District, opened in 1807, has exposed the alley to a steady stream of inebriates for over two hundred years. The decline of Charleston in the decades after the Civil War was especially hard on small corners of the city like this, which suffered generations of neglect and abuse. In recent years, local tour guides have delighted visitors with largely fictional tales of fatal duels and ghosts in this ancient alley. But what facts can we find about the real history of Philadelphia Alley, and how can that history help us preserve its character for the future?

The man responsible for the genesis of Philadelphia Alley was a Charlestonian of Scots ancestry named Francis Kinloch. In three separate transactions in 1751, 1757, and 1766, Mr. Kinloch purchased three adjacent parcels of land on the north side of Queen Street, just a bit east of Church Street. These acquisitions combined to form a broad rectangular lot that extended a sizeable distance north of Queen Street. Here Mr. Kinloch built a genteel house facing Queen Street for himself and his family, behind which he erected four tenement houses for rental purposes. To facilitate access to the rental tenements, he created a narrow passageway, or court, leading northward from Queen Street, which became known as Kinloch’s Court.

In acquiring this property and building five dwellings, Francis Kinloch was not embarking on a profit-driven development scheme. Rather, he was simply trying to create a comfortable and stable income to sustain his family after his death. In a codicil to his will drafted in 1766, Kinloch specified that all of the property he had purchased on the north side of Queen Street, including “the lane leading from Queen Street to Kinloch Court” and “the Houses thereon now building,” was to be entrusted to Gabriel Manigault and his son Peter, who were to dispose of the land for the benefit of his estate. Kinloch’s widow, his son, Cleland, and a daughter, however, were to be allowed to occupy separate tenements on the property, free of rent, for the rest of their natural lives. Kinloch also ordered that “the Fence between my Garden and Kinloch Court [is] to Remain for ever as a line between the said places.” At the time, the Kinloch family was nestled in a pleasant, thinly populated neighborhood, living peacefully in the shadow of St. Philip’s Anglican Church.

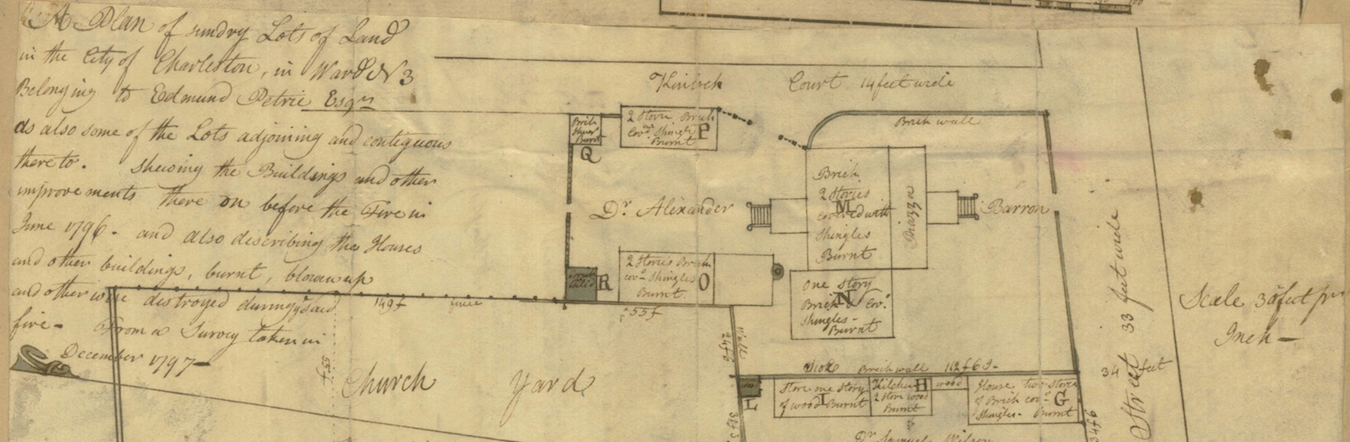

Contrary to the will of Francis Kinloch, his executors did not sell his property in Queen Street after his death in 1767. In February 1794 Francis Kinloch Jr. and his brother Cleland sold the property to Dr. Alexander Baron. Shortly thereafter, on 13 June 1796, a great fire swept through this part of Charleston. According to John Drayton’s View of Carolina (1802), the fire consumed most of Union Street, all of Kinloch’s Court, all of Church Street from Broad to St. Philip’s Church (with five exceptions), Chalmers and Beresford’s Alleys, and the north side of Broad Street from the beef market (modern City Hall) to four doors east of Church Street. In the years after this fire, rebuilding progressed slowly, and the area around Kinloch’s Court became a less-than-desirable neighborhood filled with small wooden houses. Dr. Baron divided his property bordering the Court into seven lots and had Joseph Purcell perform a survey in August 1797. The resulting plat demonstrates that Kinloch’s Court was approximately 15 feet wide and 370 feet in depth. In September 1801 Dr. Baron sold all his property around Kinloch’s Court to the two William Johnsons, senior and junior.

William Johnson Sr. (ca. 1741–1818) was a New York-born blacksmith who settled in Charleston in 1766. As a member of Charleston Battalion of Artillery during the Revolution, he was among a number of Charlestonians arrested by the British in the autumn of 1780 and imprisoned at St. Augustine. In the summer of 1781 he and the other Charleston prisoners were paroled by the British and transported to Philadelphia, where they were allowed to reside at liberty with their families until the end of the war. He was, therefore, technically not a prisoner of war during his stay in Philadelphia, as has been reported by several sources. Despite his humble beginnings, Johnson was an active force in state politics after the Revolution and provided generously for the education of his sons.

William Johnson Jr. (1771–1834) was educated at the College of New Jersey (Princeton) and read law in the office of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney in Charleston. He began public service in the South Carolina House of Representatives in 1794, and in late 1799 was elected an associate justice of the Court of General Sessions and Common Pleas. In March 1804 President Thomas Jefferson nominated Judge Johnson, as he was then known, to be an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, and Congress confirmed his appointment later that year.

In the early 1800s the Johnsons built a row of brick tenements on the site of Francis Kinloch’s former residence, and slowly began to develop the large lot to the rear. On 7 October 1810, however, another large fire raged through the neighborhood of Kinloch’s Court, from Church Street on the west to East Bay Street to the east, and ranging from Amen and Motte Streets (now included in Cumberland Street) as far south as Broad Street. The conflagration was eventually checked by the exertions of volunteer firefighters, the militia artillery battalion, and local residents, but the narrowness and irregular paths of some of the streets hindered their efforts. Immediately thereafter, a number of angry citizens began to voice their concerns about the need to re-evaluate the methods of fire prevention and suppression in Charleston. A number of citizens met in the Exchange Building on 24 October to discuss such matters, and resolved to submit a petition to the city and the state to widen and straighten several streets.

In the early 1800s the Johnsons built a row of brick tenements on the site of Francis Kinloch’s former residence, and slowly began to develop the large lot to the rear. On 7 October 1810, however, another large fire raged through the neighborhood of Kinloch’s Court, from Church Street on the west to East Bay Street to the east, and ranging from Amen and Motte Streets (now included in Cumberland Street) as far south as Broad Street. The conflagration was eventually checked by the exertions of volunteer firefighters, the militia artillery battalion, and local residents, but the narrowness and irregular paths of some of the streets hindered their efforts. Immediately thereafter, a number of angry citizens began to voice their concerns about the need to re-evaluate the methods of fire prevention and suppression in Charleston. A number of citizens met in the Exchange Building on 24 October to discuss such matters, and resolved to submit a petition to the city and the state to widen and straighten several streets.

News of the recent Charleston fire traveled northward, and by the end of October the city learned that the citizens of Philadelphia were gathering funds for the relief of Charleston’s sufferers. The citizens of Philadelphia had also sent aid following the Charleston fire of 1796, and in return Charleston had collected aid for the indigent victims of a yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia in the autumn of 1798 (see [Charleston] City Gazette and Daily Advertiser, 1, 2, and 3 October 1798). Now in 1810, Philadelphia was determined to repay that kindness by being “the first, if not the most generous contributor” to the sufferers in Charleston (see Charleston Courier, 31 October 1810). By mid-November the intendant (mayor) of Charleston acknowledged receipt of $6,000 in aid from Philadelphia, and by the end of the month a further $2,000 arrived (see [Charleston] City Gazette and Daily Advertiser, 21 and 27 November 1810).

During the month of November 1810, a French refugee of the Haitian Revolution named John Sollée published a series of letters in the Charleston City Gazette endorsing the creation of a public square. A resident of Charleston for sixteen years, Sollée noted that much of the area burned by the fire of 1796 was still in ruins, and over the years had become infested with “numberless nests of nuisances.” Although he did not own property in the neighborhood, Sollée had much to say about the redevelopment of the burned area. Besides advocating the creation of a large public square at the intersection of Amen and State Streets, he also endorsed the widening and renaming of several streets. Since William Johnson held title to the Kinloch’s former property, for example, Sollée advised the city “to make a street of Kinloch’s Court and call it Johnson Street.” Sollée’s advice was largely ignored by the city and the state, but the attention and advocacy of the neighborhood in general did push forward the movement to improve the area around Kinloch’s Court.

On 27 November 1810 the intendant (mayor) and wardens (council members) of Charleston submitted to the state legislature a petition from a number of inhabitants seeking permission to widen, open, and rename several streets that had been damaged in the recent fire. On 30 November a legislative committee reported their approval of the plan, and began drafting a bill to answer the request of the petition. Three weeks later, on 20 December 1810 the South Carolina General Assembly passed an act (No. 1971) authorizing the intendant of Charleston to “open Kinloch’s Court as a street,” to widen and extend several other Charleston streets, and to “name, alter, and change the name of the said streets.”

The following week a correspondent to the Charleston Times, calling himself “An Old Whig,” stated that he had only recently read John Sollée’s letters to the City Gazette and was appalled by his proposal “to change the names of three of those streets [i.e. Chalmers, Motte, and Kinloch] from the highly respectable ones which they now have, to others without any one cause whatever.” He extolled the contributions of these old Charleston families and urged the city to honor them by retaining the present street names. Sollée countered two days later, stating that the current owners of these properties, and the current city leaders, had the right to do whatever they judged best. In the Charleston Times of 31 December 1810, Sollée also gave a brief history of the property in question:

The following week a correspondent to the Charleston Times, calling himself “An Old Whig,” stated that he had only recently read John Sollée’s letters to the City Gazette and was appalled by his proposal “to change the names of three of those streets [i.e. Chalmers, Motte, and Kinloch] from the highly respectable ones which they now have, to others without any one cause whatever.” He extolled the contributions of these old Charleston families and urged the city to honor them by retaining the present street names. Sollée countered two days later, stating that the current owners of these properties, and the current city leaders, had the right to do whatever they judged best. In the Charleston Times of 31 December 1810, Sollée also gave a brief history of the property in question:

“Kinloch’s Court was formerly the private property of the Kinloch family. In 1794, that property was sold to Dr. Baron, who, after the fire of 1796, sold it to Judge Johnson, who now stands in the full right of the Kinloch family; and certainly the respectability of the Johnson family is too conspicuous and too well-known in this city, to say anything further about it.”

On 30 January 1811, Charleston’s City Council passed an ordinance to assess and compensate property owners around Kinloch’s Court, and other streets, for the purpose of widening and opening them. This ordinance also formally changed the name of Kinloch’s Court to Philadelphia Street (not Alley). The proceedings of City Council from this era do not survive, however, so it is not possible to determine how this street’s new name was selected. John Sollée’s earlier suggestion that the name be changed to Johnson Street was clearly not endorsed by the Johnson family. Neither William Johnson senior or junior was a member of City Council, but it is possible that one of these men suggested the new name to council. The street was, after all, formerly part of their property, and they had some interest in it. The elder William Johnson may have felt some real attachment to the city of Philadelphia, where he sojourned during the final years of the Revolution. In his Traditions and Reminiscences of the American Revolution In the South, published in 1851, his son, Dr. Joseph Johnson, included several pages praising Philadelphia for its kindness to his family during that war. Alternatively, William Johnson, John Sollée, or another Charlestonian may have suggested the name Philadelphia Street to council as a gesture of thanks for the relief money supplied by that city in 1796 and again in 1810. In either case, the name reflects the ancient connections between the two cities, and celebrates a long tradition of mutual generosity.

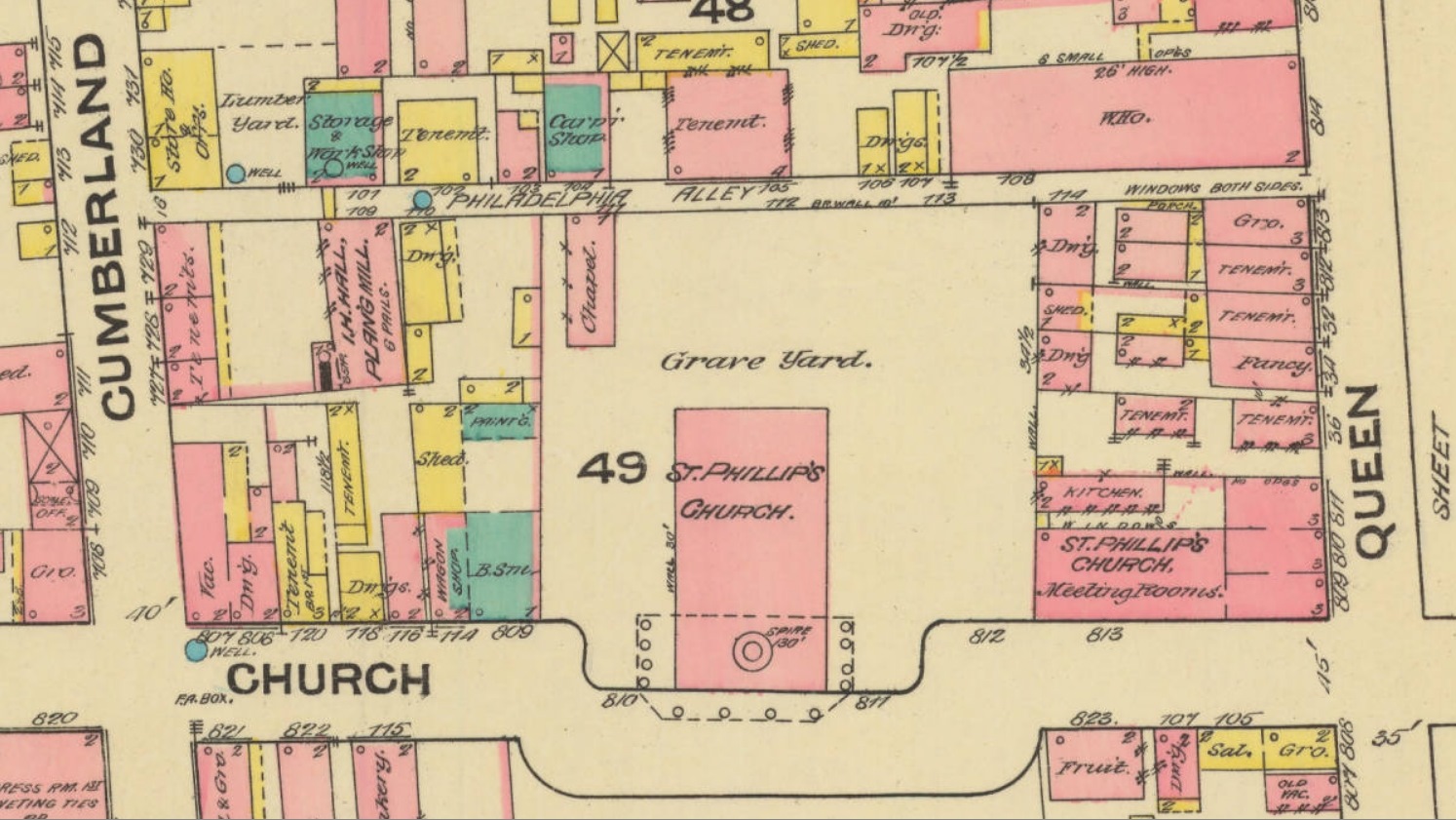

Once the northern end of the newly created Philadelphia Street was opened in 1811, it extended from Queen Street northward to Amen Street. Amen Street was a one-block street that ran parallel to and joined with Cumberland Street, then also just one block in length. Amen Street was closed and obliterated in 1838-39, however, when the City of Charleston extended Cumberland Street eastward and widened it to its present configuration. As a result of this change, the northern end of Philadelphia Street was shortened by approximately sixty feet.

For many decades after this passageway was shortened, maps of Charleston and the city directories continued to label it “Philadelphia Street” rather than “Philadelphia Alley.” At some point in the early twentieth century, apparently through common use rather than by Council ordinance, the street was demoted to an alley. By 1952, when the City of Charleston published a list of its “officially accepted streets,” the name “Philadelphia Alley” was endorsed as the legitimate designation.

After completing a beautification project in Philadelphia Alley in 2006, the City of Charleston asked me to write the write the text for a small bronze plaque to be erected in the center of the alley. Reducing two and a half centuries of history down to 100 words was pretty tough, but I did my best. The text was approved by the city and I was given a chance to proof-read the layout created by the fabricator. It looked perfect. When Mayor Riley pulled the curtain away to unveil the plaque, however, I immediately saw that the fabricator had changed the date "1766" to "1776" in the first line. Oh well, I did my part.

Philadelphia Alley is a narrow, unpretentious pathway whose history has been marked by a series of dramatic events. After two destructive fires, and after having its northern end amputated, the alley has settled into a quiet, shady stasis that attracts tourists and residents alike. The recent improvements made by the City of Charleston and the French Quarter Neighborhood and Improvement Associations have given new life to this quaint street, and form a promise that it will continue to inspire visitors for generations to come.

NEXT: ShakeOut 2017

PREVIOUSLY: Dutch Town

See more from Charleston Time Machine