Segregation and Desegregation at the Charleston County Public Library, 1930–1965

Processing Request

Processing Request

The Charleston County Public Library opened its doors in 1931, but welcomed visitors unequally and conditionally until the early 1960s. Like nearly every other institution existing in the American South during that era, the Charleston Free Library, as it was then known, maintained separate facilities and unequal collections for two classes of customers identified as either Black or white. This divisive practice continued until November 1960, when the opening of a new, racially-integrated library on King Street shocked some members of the community and signaled the twilight of a prejudicial tradition.

Part 1: Segregation

The racial segregation of libraries within the Charleston community commenced long before the creation of the present county system. The Charleston Library Society, now a welcoming and inclusive institution, was founded in 1748 as a private reading club for white colonial gentlemen. Although its membership became less exclusive and less masculine over the course of the nineteenth century, the organization did not admit persons of African descent who formed the majority of the local population at that time. On two occasions in the early twentieth century, philanthropist Andrew Carnegie offered large sums of money to expand the Charleston Library Society into a free institution open to the general public. On both occasions, however, its officers declined the offer, believing that the projected expansion would include the “undesirable” necessity of admitting “colored tax payers.”[1]

The momentum to establish a network of free libraries serving all citizens of Charleston County coalesced among a group of progressive women in the late 1920s. The Charleston Museum had started its own private circulating library several years earlier, and director Laura Bragg sought to expand the concept into a larger, publicly-funded service. She and other members of the Charleston Civic Club established contact with the Rosenwald Fund and the Carnegie Foundation, both of which agreed to supply seed money for a public library system if the city and county of Charleston would appropriate matching funds. Local officials rejected the project in 1929, but in early 1930 agreed to make the necessary appropriations.[2] Supporters organized an all-white board of trustees and incorporated the Charleston Free Library that May, then spent the rest of the year preparing for public service.

The money promised by the Rosenwald Fund, established in 1917 to promote African-American education, was predicated on the fulfilment of certain well-known conditions. Before releasing the first disbursement to the trustees of the Charleston Free Library in November 1930, a Rosenwald representative articulated the terms of their agreement: “That the library shall give service to both white and colored people with equal opportunities to both and with facilities adapted to the needs of each group. It is further understood that the fund referred to above is intended for county wide library services and that a central building for both white and colored shall be provided from other funds.”[3] After the Charleston trustees acknowledged and accepted these conditions, agents of the Rosenwald Fund released the first in a series of five annual payments.

In compliance with their 1930 agreement, the trustees of the Charleston Free Library envisioned a county-wide network of segregated branches linked to a larger central facility. Of the 101,000 citizens enumerated in Charleston County by the U.S. Census of 1930, more than 62% resided within the peninsular limits of urban Charleston between the rivers Ashley and Cooper. The trustees’ initial efforts focused, therefore, on the creation of a principal branch in the city as quickly and inexpensively as possible. Their fledgling main library opened to the public on the first of January 1931, occupying a portion of the old Charleston Museum at 121 Rutledge Avenue. From its first day of service, this temporary facility was nominally integrated, albeit in a conditional manner. Most of the books and the associated card catalogs were reserved for white customers, but the main branch also housed a separate and smaller “colored collection” that was available, at least in the earliest months, during a limited schedule of “colored hours.”[4]

To satisfy its obligations to the Rosenwald Fund, the trustees of the Free Library sought to provide more extensive service to Black citizens living within the City of Charleston and those distributed across the broad coastal county. Library and Museum Director Laura Bragg established an agreement in the autumn of 1930 with Susan Dart Butler, who in 1927 had established a circulating library for African Americans at Dart Hall, a former school house standing at the southwest corner of Kracke and Bogard Streets (see Episode No. 43). Butler agreed to lend the use of Dart Hall to function as both a branch of the nascent library system and, in effect, the main hub of county-wide service to the Black community.

By the beginning of August 1931, the Charleston Free Library system included a main branch within the Charleston Museum, four small branches for white citizens (at McClellanville, Mount Pleasant, Edisto Island, and St. Paul’s Parish), and three branches for Black citizens (one small library on Edisto Island, one at St. Peter’s Catholic School on Society Street, and a larger collection at Dart Hall). Later that autumn, the institution launched an enduring campaign of mobile library services to citizens residing in rural parts of the county (see Episode No. 196). During the ensuing three decades, the library system deployed two bookmobiles traveling along segregated routes. Institutional records of this service consistently identify the older and less-reliable of the two vehicles as the “colored” or “negro” bookmobile, which ferried books to and from its home base at the segregated Dart Hall Library.

The Free Library detached itself from the Charleston Museum in the autumn of 1934, when the board of trustees purchased a large mansion at 94 Rutledge Avenue built in 1854 as a single-family residence. For the next twenty-six years, this antebellum structure served as the library system’s principal branch and the hub of its county-wide extension services to white citizens. The practice of keeping separate hours of service for Black and white patrons at the main branch appears to have ended in 1934, but the new building, like its predecessor within the old museum, included a small, segregated collection of books reserved for the African-American readers who occasionally visited the predominantly-white facility. The matter of separate restrooms and water fountains for the two classes of citizens did not arise because the antiquated building offered no such facilities to the visiting public.

Census data collected in 1940 and 1950 demonstrated the steady increase of Charleston County’s white population, while the so-called “Great Migration” of African Americans from the South to the North contributed to the steady decline of their local numbers after reaching an all-time high in 1920. During an era of demographic transition following World War II, the county government partnered with private citizens to fund the construction of several new public library branches that the community tacitly acknowledged to be white-only facilities (like the Cooper River Memorial branch). Instead of building new branches to serve African American readers, the Charleston Free Library system continued to maintain circulating collections of books, called “deposits,” at a number of black schools throughout the community.

During its first three decades of operation, therefore, most of the services provided by the Charleston Free Library were segregated along traditional racial lines, while the system’s main branch was nominally integrated in a limited and conditional manner. Persons of African descent occasionally visited the Rutledge Avenue facilities between 1931 and 1960, but their presence was sufficiently unobtrusive to escape the notice of most of the white community. Due to the small scope of the segregated “colored collection” within that main branch, combined with the discomfort of racial anxiety associated with visiting a predominantly-white facility, members of Charleston’s Black community generally resorted to the Dart Hall branch on Kracke Street.

Part 2: Desegregation

The first public step in dismantling the customs of racial segregation within the Charleston County library system commenced in November 1960, with the opening of a newly-constructed, integrated main branch at 404 King Street. Although no members of the library’s staff or board of trustees issued a statement explaining this significant change in policy, their decision was the logical product of the turbulent political conditions of the late 1950s. The gestation of this controversial building occurred during a rising tide of civil rights activity, both locally and across the United States, that convulsed and transformed the nation.

The trustees of the Charleston Free Library began planning a new main branch in early 1954, just before the United States Supreme Court issued its landmark ruling in the case of Brown v. Board of Education. That decision deemed unconstitutional the political fiction of “separate but equal” that had flourished in the segregated South since the 1890s. While the 1954 court ruling applied specifically to public school facilities, citizens understood that it confirmed the equal-protection clause of the 14th Amendment more generally. If the federal government required public schools to integrate, the desegregation of other publicly-funded institutions and services like parks, transportation, and libraries would soon follow.

The resolution of Brown v. Board of Education might have influenced the individual staff and trustees of the Charleston Free Library, but none recorded their thoughts on the matter. Records of board meetings and activities at various branches contain no references to conversations about the politics of civil rights nor any modification of the library’s customary policies. References to desegregation were absent from the county-wide referendum campaign that voters approved in November 1954, allocating $750,000 for the construction of a state-of-the-art main library within the urban landscape of the City of Charleston. After several years of negotiations, the library’s trustees secured a site for a new building at the southeast corner of King and Hutson Streets in early 1957 and later the same year approved designs for the structure’s exterior and interior. Plans for the two-story library included restrooms, typing booths, meeting rooms, an auditorium, and floor space allocated for reference books, periodicals, fiction, non-fiction, local history, and children’s services, but identified no space or equipment reserved for the exclusive use of either white or Black citizens.[5]

Although the proposed library’s mid-century-modern design, featuring stark lines of glass and steel, aroused scathing criticism from some quarters in 1958, the board of trustees stood their ground and moved forward with construction in 1959. Conservative members of the Charleston community who embraced racial segregation apparently interpreted the library’s large expense and modern design as evidence of a facility intended for the exclusive use of white citizens, but the more liberal board of library trustees, chaired by Kentucky-native Estella Hebden Fitch (1903–1995), made no such statements. Despite their silence, the trustees of the public library evidently intended the new branch to be both aesthetically and culturally progressive.

In the meantime, a nationwide campaign for the expansion of civil rights gripped the United States in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education. Marches, pickets, and other non-violent actions mushroomed across the country, including within Charleston County. In November 1958, for example, several Black citizens attempted to make use of the City of Charleston’s white-only Municipal Golf Course on James Island. They were turned away, but later filed a lawsuit that worked its way through the courts to over two years. More generally, the inhabitants of the Southern States witnessed a wave of sit-in demonstrations at lunch counters that began in Greensboro, North Carolina, on 1 February 1960 and quickly spread across the region.

On 16 March 1960, for example, seven Black teenagers in Greenville, South Carolina, visited the main branch of the city’s public library, traditionally reserved for white patrons. A librarian asked the students to leave and use a nearby “colored” branch, but they sat down and stated that their parents were tax-paying citizens whose civil rights were protected by the Constitution. Police officers called to the scene also asked the teenagers to leave, but they refused, were arrested on charges of disorderly conduct, and transported to jail. A civil rights attorney immediately posted bail for the seven students and later filed a lawsuit on their behalf to assert their right to use Greenville’s main library.[6]

In response to the profusion of anti-segregation activities across the South in early 1960, white supremacist members of the Ku Klux Klan launched a series of counter demonstrations across South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida. On a single Saturday night in late March, Klansmen set aflame wooden crosses in at least thirteen counties in South Carolina, the total number reportedly between fifty and a hundred across the state. Most were placed in rural and suburban locations, but one burning cross appeared at 270 Ashley Avenue in downtown Charleston, then the family residence of J. Arthur Brown, president of the local chapter of the NAACP.[7]

On April 1st, 1960, less than a week after the cross-burning incident, twenty-four Black students from Charleston’s Burke High School staged a sit-in protest at the white-only lunch counter of the Kress department store on King Street. Police arrested the teenagers for trespassing and took them to jail, where J. Arthur Brown immediately paid their bail. In a condescending essay published in Charleston’s principal newspaper, the conservative News and Courier editor Thomas Waring derided the non-violent Kress demonstration as an “embarrassing show” for the Black community.[8]

On April 28th, a group of Black students in Columbia held a similar sit-in protest at the main branch of the Richland County Public Library. The veteran white librarian on duty described the event as “pointless” because, as she told a reporter, the seven-year-old building had “always been open” to Black citizens with “no restrictions whatever.” She noted, however, that African-Americans were required to register for library cards at a separate branch reserved for Black members of community. The Richland County policy evidently mirrored that shared by public libraries in both Charleston and Spartanburg, where African Americans were ostensibly permitted to use the main branch but strongly encouraged to patronize the segregated “colored” branches.[9]

Construction of Charleston’s new main library was expected to conclude during the late spring of 1960, but the usual delays postponed its completion to late autumn. Nevertheless, some members of the staff were upbeat about its anticipated improvements. At a board meeting held on June 29th, long-serving head librarian Emily Sanders, a native of Summerville, expressed confidence “that the opening of the new building will have a terrific impact on the community[,] and we can expect to have more Negroes, at first, than we usually have using the main library.”

At the end of July 1960, a civil-rights attorney representing the seven students arrested in Greenville filed a federal lawsuit against the city’s public library. To counter that move in early September, the board of the Greenville library system deployed a defensive strategy utilized by numerous other Southern institutions facing similar pressure: They closed the library system entirely to both Black and white customers. African-American citizens could not claim unfair discrimination, they asserted, if the facilities in question were closed to everyone. As a result of this tactic, the court dismissed the civil-rights case on September 13th, but advised the plaintiffs’ attorney to re-file the suit if the library re-opened with its customary policy of racial segregation. Rather than face continued litigation and negative publicity, the library’s board of trustees relented. The main branch of Greenville’s public library reopened as an integrated facility on Monday, 19 September 1960.[10]

Meanwhile, trustees of the recently-renamed Charleston County Library prepared to open the much-anticipated main branch. At some unknown point between 1954 and November 1960, they determined to open the new King Street library to all visitors without the traditional barriers of racial segregation. The trustees might have planned this change during the initial stages of the building’s gestation, or their sympathies might have evolved in response to more recent civil rights agitation. Staff members received the final deliveries of furniture and books for the new facility during the early days of November, while American voters living beyond the conservative South elected John F. Kennedy to serve as President of the United States. Before Thanksgiving, Estella Fitch, president of the board of library trustees, conferred with the manager of Charleston County, Albert Hair Jr., to minimize the potential for negative publicity surrounding the opening of an integrated public facility within the heart of urban Charleston. Speaking to a local reporter about the soft opening of the new library, Mr. Hair said “the new library will be opened and put into use without any fanfare. We plan no formal opening ceremonies. Just open up, and go to work helping the public.”[11]

On Saturday, November 26th, the same day that a U.S. district judge ordered Charleston’s Municipal Golf Course to admit African-Americans, Mrs. Fitch and her fellow trustees hosted a quiet private reception for city and county officials within the newly-finished library at 404 King Street. The following afternoon, staff welcomed 1,400 visitors during a brief open house to inspect the modern building ridiculed in the press as architecturally offensive.[12] The new main library officially opened for public service at 10 a.m. on Monday, 28 November 1960, with no ceremony or fanfare.

Among a number of positive articles and letters published immediately after the library’s opening, the News and Courier heralded the new building and praised the board of trustees for delivering a first-rate amenity to the people of Charleston.[13] The newspaper’s conservative editor continued that theme in an essay summarizing his view of the library’s role in the community: “We live not in One World, to use the favorite phrase of ‘liberals,’ but in a world sharply divided by cold war. . . . Reading books can help Charlestonians to grasp the realities of the modern world. They can learn the uniqueness of the United States and its traditions of personal freedom. By reading, they can put on the armor of knowledge which will prevent them from becoming serfs of state socialism. We firmly believe that those who read are those who will be free.”[14]

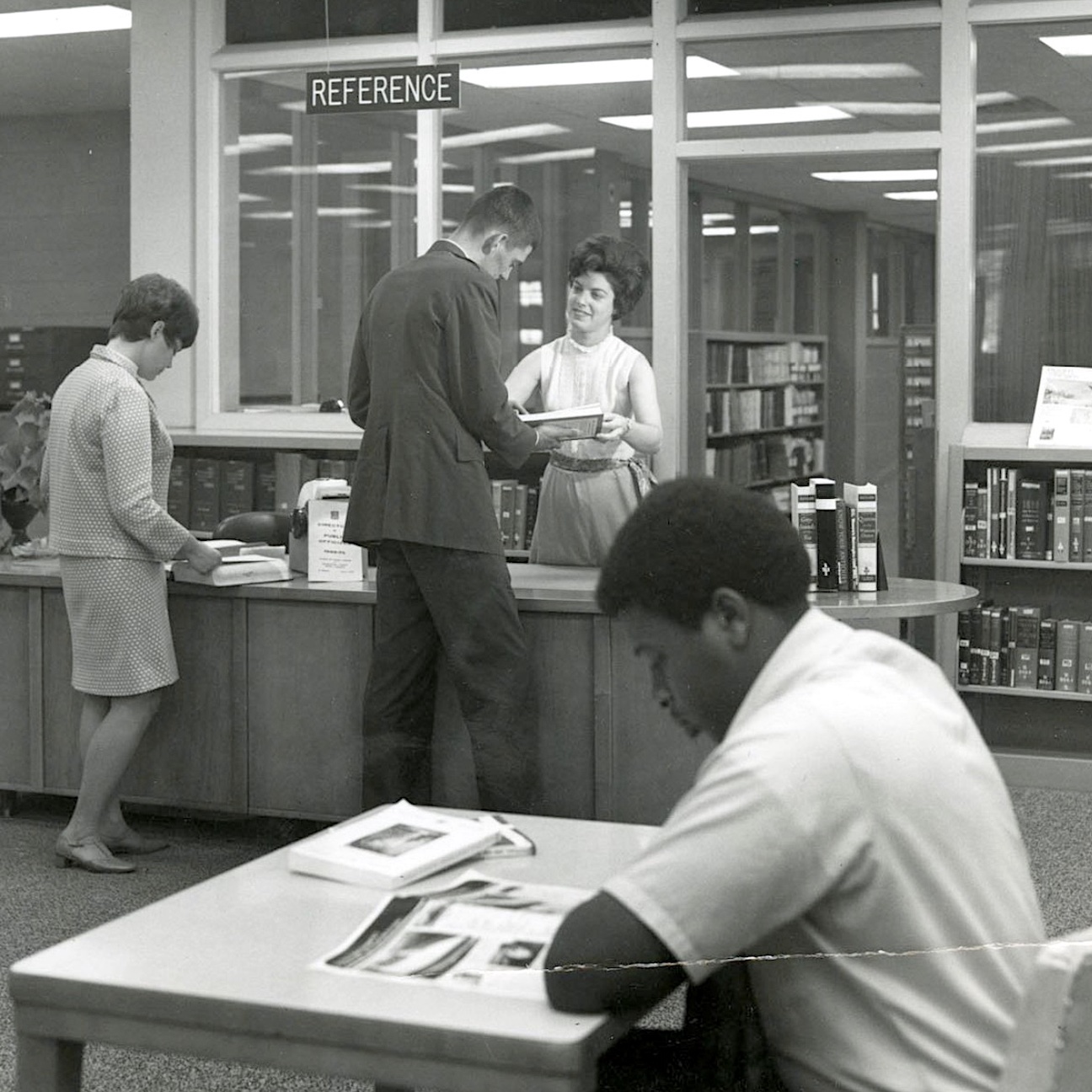

By the early days of December 1960, visitors to the new facility began to notice the presence of increasing number of African-American citizens who browsed the shelves, read quietly at tables, and posed questions to members of the all-white staff. At a board meeting on December 13th, head librarian Emily Sanders proudly relayed positive comments about the building from visitors, and reported also its “heavy use by negroes, more than in the old building.” Her enthusiasm was not shared by everyone, however. One library visitor relayed her experience in a brief letter to the sympathetic newspaper editor: “During the 15 or 20 minutes I was roaming around the new building, the ratio of colored to white was 3 to 1 in favor of the colored. I bade a fond farewell to the members of the staff . . . and re-joined our [segregated] Charleston Library Society.”[15]

Under the headline “County Library Fully Integrated,” the News and Courier published a negative summary of the social conditions at the new facility on December 22nd: “The change has taken place quietly, and apparently without incident. Library officials declined to comment for publication. They also declined to concede that there had been any change in racial policy. Their unofficial position appeared to be that there had been a certain amount of integration at the old library in Rutledge Ave., and that while the degree of integration might have changed, the policy itself remained the same. It is a fact, however, that Negroes are appearing at the new building in far larger numbers than appeared at the old site on Rutledge avenue. At the old building[,] Negroes occasionally used the reading rooms, but their presence was the exception rather than the rule. . . . The old arrangement which reserved the main building for white persons apparently has been dissolved by the move to Marion Square.”[16]

Thomas Waring continued this negative theme in an editorial published the following day: “The experiment was undertaken by those in charge of the library on their own initiative, so far as the News and Courier can learn. We are aware of no pressure from federal government or other sources. Accepted so far without incident, the interracial use of the library is perhaps the most significant change in local race relations since the opening in 1948 of the Democratic primaries to Negro voters. That took place under orders of a federal court.” “It would be ironic,” Waring predicted, “if the expensive new library building should turn out in fact to be the Negro branch, while white people patronize other branches.”[17]

On the last workday of 1960, Emily Sanders telephoned a representative of the South Carolina State Library in Columbia to commiserate. “The News & Courier is after them again, about integration,” she complained. The newspaper had published a “very nasty article” about the library before Christmas, written by editor Waring, said Sanders, “because the reporters refused to do it.” Waring’s subsequent and “equally obnoxious editorial” was prelude to further derision in the paper’s latest edition. The state librarian noted, however, that Miss Sanders “seemed unperturbed, and said that she & [board president] Mrs. Fitch felt that as long as they have the N&Cs enmity they are on safe ground!”[18]

Inspired by the inauguration of President Kennedy on 20 January 1961, the News and Courier published another negative editorial about the local library that echoed Waring’s earlier prejudicial remarks. “Provision of books not social reform, is the purpose of the library,” proclaimed the editor, who concluded that “the board of trustees has lost touch with public opinion.”[19] While some subsequent letters to the editor amplified Waring’s caustic rhetoric and decried racial integration as an atheistic communist conspiracy, the majority of the community praised the new library and chastised the News and Courier for belittling its progressive achievement.[20]

In the months after the controversial opening of the integrated public library in November 1960, the racial segregation practiced in Charleston’s other branches disintegrated. Rather than proclaiming the definitive end to the practice of maintaining separate facilities and services, the surviving administrative records contain only cryptic references that suggest a gradual termination of these traditional practices. The minutes of the library’s board of trustees in October 1962, for example, mention a recent meeting of its Civil Rights Advisory Committee. In August 1963, the library’s director reported the presence of “a large number of negroes” at the “Village” branch in Mount Pleasant, and smaller numbers visiting the Cooper River Memorial branch. At the same time, references to the “colored” bookmobile were replaced by reports of “bookmobile No. 2.”

The practice of physical segregation ceased within Charleston County’s public library system during the early 1960s, but the topic remained in local headlines as the county’s public schools began the process of racial integration in the autumn of 1963. The library’s final reference to this prejudicial legacy appears among the minutes of a meeting that took place on 4 March 1965. On that day, Head librarian Emily Sanders informed the board of trustees that she had received a memorandum from the South Carolina State Library regarding the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, which mandated the desegregation of public services. Without ceremony or commentary, the trustees of the Charleston County Public Library formally affirmed the institution’s full compliance with the federal law. The era of segregation within the community’s public libraries had officially ended.

[1] Dan R. Lee, “From Segregation to Integration: Library Services for Blacks in South Carolina, 1923–1962,” in John Mark Tucker, ed., Untold Stories: Civil Rights, Libraries, and Black Librarianship (Champaign, Ill.: University of Illinois, 1998), 94.

[2] The library’s early history was summarized in Charleston News and Courier (hereafter CNC), 30 January 1961, page 1-B, “County Library Development Is Outlined.”

[3] Clark Foreman to Charles B. Foelsch, 17 November 1730, from the files of the Charleston County Public Library’s institutional archive.

[4] A reference to the “colored collection” at the “county” or main branch, separate from the books at the Dart Hall branch, appears in a letter from “Librarian” to S. L. Smith of the Rosenwald Fund, 1 February 1936, found in CCPL’s institutional archive.

[5] At a board meeting on 10 December 1957, the library trustees approved “floor plans” and “a contemporary exterior design” for the new main library building on King Street, and voted to omit henceforth the word “Free” from the name of the Charleston County Free Library. Copies of the original blueprints are found among the institution archives at CCPL.

[6] CNC, 17 March 1960, page 5-D, “7 Greenville Negroes Arrested In Library”; CNC, 19 May 1960, page 4-C, “Warrant Suspension Asked In Sit-Down”;

[7] CNC, 27 March 1960, page 1-A, “4 Crosses Burned In City, Area”; CNC, 28 March 1960, page 4-B, “Cross Burnings Noted Across South Carolina”; Charleston CEP (hereafter CEP), 28 March 1960, page 3-A, “13 Cross Burnings In S.C. Verified”; CEP, 28 March 1960, page 4-B, “KKK Burns Crosses In Four States.”

[8] CNC, 2 April 1960, page 1-B, “24 Arrested Here In Demonstration”; CNC, 4 April 1960, page 8-A, “Embarrassing Show.”

[9] CNC, 29 April 1960, page 6-C, “‘Pointless’ Protests Held In Columbia”; CNC, 21 September 1960, page 6-B, “Negroes Using 3 Libraries.”

[10] CNC, 29 July 1960, page 13-C, “Integration Suit Filed in Greenville”; CNC, 3 September 1960, page 1-A, “City Library Closes At Greenville”; CNC, 4 September 1960 (Sunday), page 9-B, “Library Suit Is Answered By Greenville”; CEP, 13 September 1960, page 9-B, “Greenville Library Suit Is Dismissed”; CNC, 20 September 1960, page 1-A, “Greenville Library Admits Negroes.”

[11] CNC, 24 November 1960, page 1-B, “Public May Inspect Library During Open House Sunday.”

[12] CNC, 27 November 1960, page 14-A, “Visitors Welcome At Library Today”; CNC, 28 November 1960, page 1-B, “1,400 Inspect Facilities at County’s New Library”; CEP, 29 November 1960, page 1-A, “U.S. Court Orders Links Integrated.”

[13] CEP, 28 November 1960, page 1-B, “New County Library Swings Its Doors Open To Patrons”; CNC, 29 November 1960, page 1-B, “County’s New Library Opens”; CNC, 1 December 1960, page 6-A, “New Library”; CNC, 5 December 1960, page 8-A, “County Library”; CEP, 7 December 1960, page 33, “Library Is ‘Filled With Advantages.’”

[14] CNC, 30 November 1960, page 6-A, editorial, “The Need to Read.”

[15] CNC, 25 December 1960, page 6-A, “County Library.”

[16] CNC, 22 December 1960, page 1-B, “County Library Fully Integrated.”

[17] CNC, 23 December 1960, page 10-A, “Integrated County Library.”

[18] The text of a note stemming from this telephone conversation is transcribed in Suzanna W. O’Donnell, “Equal Opportunities for Both: Julius Rosenwald, Jim Crow and the Charleston Free Library’s Record of Service to Blacks, 1931 to 1960” (Master’s thesis, University of North Carolina, 2000), 44.

[19] CNC, 20 January 1961, page 6-A, “Our New President.”

[20] See, for example, CNC, 15 December 1960, page 10-A, “County Library”; CNC, 24 January 1961, page 6-A, “County Library”; CNC, 11 February 1961, page 6-A, “Integrated Library”; CNC, 12 April 1961, page 6-A, “County Library”; CNC, 22 April 1961, page 6-A, “Opening Wedge.”

NEXT: The Shaw Community Center: A Living Memorial to Civil Rights Progress

PREVIOUSLY: John L. Dart, Champion of Education

See more from Charleston Time Machine