Savannah Highway: The Private Roots of a Public Thoroughfare

Processing Request

Processing Request

Can you imagine Savannah Highway as a narrow toll road traversing a patchwork of rural plantations? The present broad ribbon of asphalt covers a modest country path created more than two centuries ago by a private corporation. Its purpose was to funnel agricultural goods, animals, and people from the hinterland to markets in urban Charleston, across the first bridge connecting the city to the Parish of St. Andrew. Its formal transformation into a public highway in 1921 represents a major turning point in the history of the community now called West Ashley.

Generally speaking, the phrase “Savannah Highway” refers to a public highway stretching southward from the City of Charleston to the City of Savannah. The citizens of that Georgia metropolis describe this same road as the “Charleston Highway,” proving that its proper name depends on one’s point of view. For the purposes of the present conversation, I’m focusing on the north-easternmost segment of the highway, extending southward from the Ashley River to an intersection with what is now called Bee’s Ferry Road. This nine-mile stretch of asphalt differs from the rest of the Savannah Highway and all of the surrounding public thoroughfares because it began as a privately-owned turnpike. For more than a century after its creation, the private character of this road exerted a profound but forgotten influence on the development of the adjacent countryside.

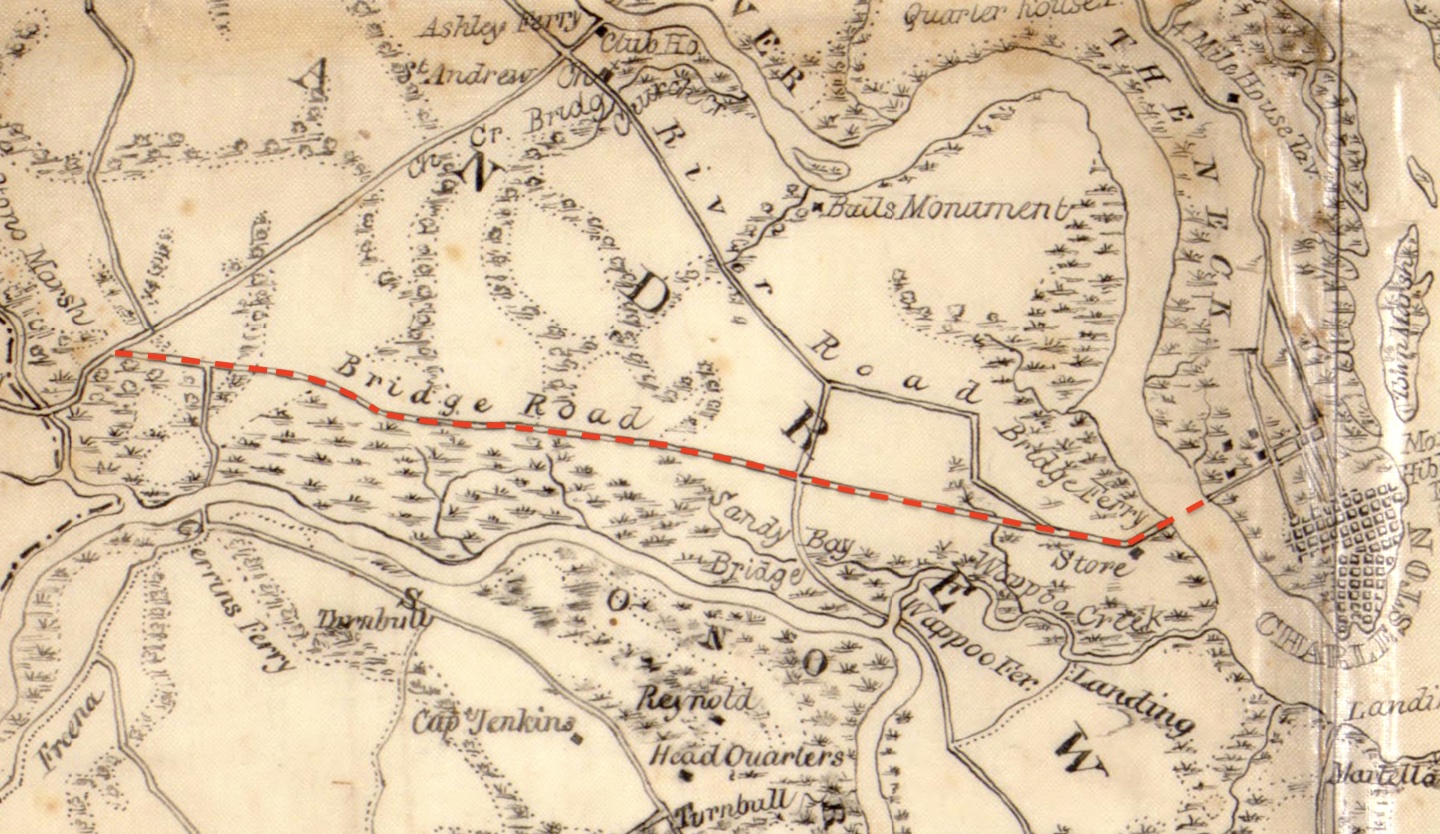

Prior to the construction of this turnpike and a related bridge in the early nineteenth century, Charlestonians wishing to visit the land west of the Ashley River had to travel nearly ten miles northward into the area of modern North Charleston, cross the river by ferry, and travel southwesterly along a road created in 1703, originally called Ashley Ferry Road but now Bee’s Ferry Road (see Episode No. 28). Country residents from anywhere west of the Ashley, including the islands, who wished to visit urban Charleston had to follow the same route across Bee’s Ferry to reach Dorchester Road and then turn southward down the Neck to reach the city. This circuitous route was long and tedious, but it was a fact of life from 1703 to 1810. Similarly, colonial-era travelers created Ashley River Road (now part of South Carolina Highway 61), to facilitate travel along a roughly north-south axis through the area defined as the Parish of St. Andrew by a provincial law of 1706 (see Episode No. 203).

The present Savannah Highway is such a busy and congested road that modern Charlestonians might wonder how earlier inhabitants survived without such a vital link through West Ashley. The community wasn’t always so vibrant, however. Prior to demise of slavery in 1865, St. Andrew’s Parish was a thinly-populated, rural landscape divided into numerous large plantations dominated by enslaved people of African descent. White property owners used public roads to transport crops to markets in urban Charleston, to bring supplies home from the city, and to carry their families to church and other social events. No one commuted to work outside the parish, and the enslaved majority enjoyed limited freedom to use any road beyond their home plantations. In general, the aforementioned public roads were sufficient for the commercial and cultural needs of early planters.

In the decades after the American Revolution and the birth of the United States, citizens in several states began exploring ways to expand the nation’s commerce through a larger network of roads and canals. Privately-funded toll roads or turnpikes became popular business ventures at the end of the eighteenth century because federal and state government were too small and too young to fund any large highway projects. Several toll roads began to appear across the Lowcountry of South Carolina during this era, but the most significant one traversed the land west of the Ashley River.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, a rumor circulated around Charleston District that a group of investors planned to open a new road through the Parish of St. Andrew, extending eastwardly from Rantowle’s Bridge (over the northeast branch of the Stono River) directly to the City of Charleston.[1] A group of citizens in the parish drafted a petition to the state General Assembly in late 1801, expressing opposition to the rumored plan. Their grievance stemmed from a longstanding practice prescribed by a South Carolina law of 1721 that required all property owners to contribute labor, tools, and materials for the routine maintenance of roads and highways adjacent to their respective properties.[2] If the legislature allowed the creation of such a new road across St. Andrew’s Parish, said the petitioners, “it would operate to the entire ruin & destruction of several plantations which are now valuable, and would materially injure the whole parish, by calling out their slaves to make a new road, thro’ deep and difficult swamps, which they would be annually and eternally at the expence of keeping or rather attempting to keep in good order.” The people of St. Andrew’s Parish would bear the burden of all that “mischief,” said the petitioners, while citizens using the proposed thoroughfare would be disappointed by the resulting “dirty, muddy roads.”[3]

The rumored plan for a new road across the Parish of St. Andrew did not formally surface until the autumn of 1808, when a group of affluent investors petitioned the South Carolina General Assembly for incorporation. The goal of the Charleston Bridge Company, as they called the venture, was to create a bridge across the Ashley River, adjacent to the City of Charleston, with causeways on either side of the river leading to the bridge. The proposed work “would be of great public utility,” said the petitioners, augmented “by the cutting of a road from the end of the causeway to be made in St. Andrew’s Parish to intersect the public road leading to Rantouls [sic; Rantowle’s] Bridge”—that is, from the Ashley River to what is now called Bee’s Ferry Road.[4]

The state legislature, composed of men familiar with the founders of the Charleston Bridge Company, approved their proposal and ratified an act to facilitate the plan on 17 December 1808. The law incorporated the company and empowered its directors to raise the necessary funds by selling shares in the corporation and running several public lotteries. The state authorized the Bridge Company to build a toll bridge over the Ashley River and “to establish a turnpike road, from the part or place in the parish of St. Andrew, where the said bridge may be there fixed or established, in a direct line, or as nearly so as they may deem expedient, until it shall intersect the public road at present leading from Charleston to Rantole’s [sic; Rantowle’s] bridge or ferry; which shall be vested in the said company, their successors and assigns in perpetuity.” The act of 1808 empowered the Bridge Company to charge tolls for the use of the bridge and turnpike and prohibited the erection of any other bridge or ferry over the Ashley River within seven miles of the proposed structure.[5]

Construction of the wooden bridge commenced in February 1810 under the supervision of William Mills of Boston. A large gang of laborers, mostly enslaved men hired by the Bridge Company, first built a long earthen causeway extending westwardly from Spring Street on the Charleston Peninsula. That site was then outside the City of Charleston, the northern boundary of which was, until 1850, Boundary (now Calhoun) Street. The Spring Street trajectory nevertheless represented the shortest path across the Ashley River, as it still does today. The wooden span measured 2,187 feet in length and thirty-three feet wide, including two sidewalks for pedestrians. The total length of the river crossing, including the bridge’s two causeways, measured 5,367 feet—just over one mile—and was completed in late August. The first bridge connecting the City of Charleston to the land west of the Ashley opened to the public on September 1st, 1810. Each traveler, including pedestrians and riders on horses and in carriages, was obliged to stop at a toll house at the west end of Spring Street and pay a toll ranging from six-and-a-quarter cents to one dollar.[6]

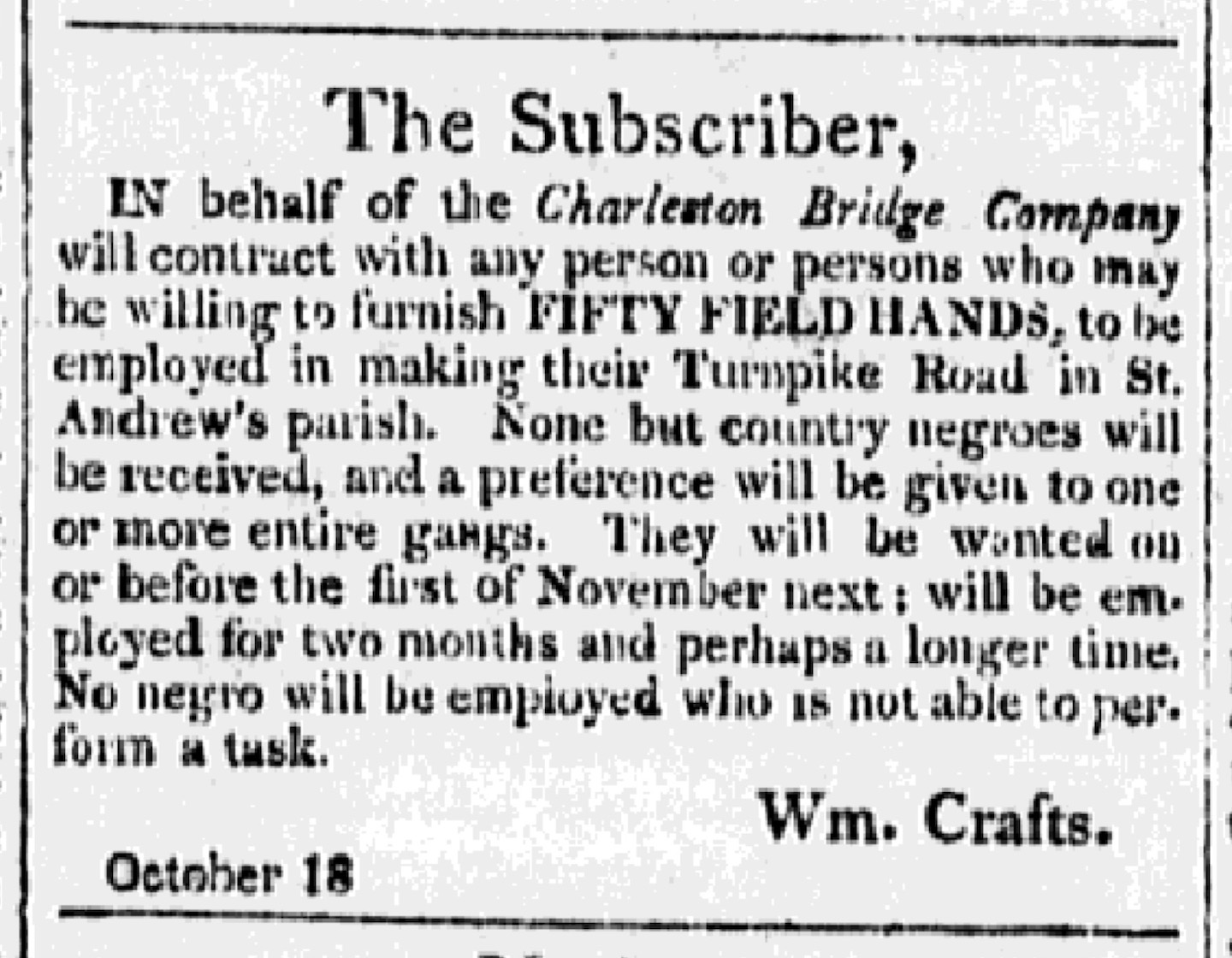

As that work neared completion in mid-July, the Bridge Company turned its attention to the task of creating the turnpike road across the rural landscape of St. Andrew’s Parish. The directors hired dozens of enslaved “field hands” from local plantations to remove trees and reshape the land with shovels and hoes.[7] Their work followed a path prescribed in 1808, cutting a remarkably straight line from Rantowle’s Bridge to the new bridge over the Ashley River, with just a few minor curves to avoid swamp lands. The result was a sandy, unpaved road sixty feet wide and nine miles long.[8] A newspaper report published at that time predicted that “the distance saved by the cutting of this road will be at the least five miles, and it is believed that the time that will be saved by avoiding the bad roads on this [i.e., on the peninsula] side of the [Ashley River] ferry, will be one hour.”[9]

On the first of August, 1811, the Charleston Bridge Company began charging a toll for the use of what it called the “St. Andrew’s Turnpike Road.” At that time, the rates of toll were the same as those charged for crossing the new bridge over the Ashley River. The company revised its fee schedule in November 1812, however, after which time all “foot passengers” (pedestrians) who paid a toll for crossing the bridge were permitted to traverse the turnpike for free.[10]

The Bridge Company later reported that it had spent $180,000 between 1809 and 1811 to build the bridge, causeways, toll house, and turnpike. That massive sum, comparable to many millions in today’s dollars, included a total of $25,000 for labor, tools, and materials to create the turnpike.[11] Although the company’s directors did purchase a few acres of land on both sides of the Ashley River under the causeways leading to the bridge, they did not purchase land from or compensate the owners of private property lying in the path of the toll road.[12] The affluent directors of the Charleston Bridge Company, empowered by their friends and relatives in the South Carolina General Assembly, apparently did not think twice about usurping a sixty-foot wide, nine-mile long swathe (that’s 7.27 acres) of their neighbor’s properties to facilitate their commercial enterprise. While the owners of some plantations lying in the path of the St. Andrew’s Turnpike might have been pleased to sacrifice a sliver of land to gain a more direct route to urban Charleston, others resented the imposition of the road and complained for generations. In either case, property owners were obliged to erect and maintain wooden fences along both sides of the toll road to keep travelers out and to restrain the wanderings of both livestock and enslaved residents.[13]

Beyond the initial costs of creating the St. Andrew’s Turnpike in 1810–11, the Charleston Bridge Company also bore legal responsibility for maintaining the toll road and keeping it in passable condition. The aforementioned South Carolina highway law of 1721, which required property owners to maintain roads adjacent to their respective properties, applied only to public thoroughfares. Citizens who had lost property to the private turnpike were, therefore, not obliged to contribute to its maintenance. Profit and legal ownership “in perpetuity” induced the Bridge Company to ensure that fee-paying travelers could safely traverse its nine-mile length.

A massive hurricane passing over Charleston on 27 August 1813 completely destroyed the three-year-old wooden bridge.[14] Two months later, the Charleston Bridge Company advertised their desire to sell the new turnpike and their legal franchise to operate a bridge over the Ashley River.[15] The corporation did not sell out, however, but kept the business afloat by commencing a ferry service in 1814, plying the half-mile distance between the surviving causeway at the west end of Spring Street and the opposite causeway in St. Andrew’s Parish.[16]

The public use of the new turnpike continued after the hurricane of 1813, and the Bridge Company continued to maintain the toll road as it retired debts stemming from the construction of the short-lived bridge. The price of the turnpike toll during the ensuing years is unknown, however, as the Bridge Company simply directed travelers in 1814 to inquire at the toll house to learn the various rates of passage.[17] The volume of traffic along the new road was exponentially smaller than that of the present highway, of course. A petition submitted to the state legislature in 1816 complained that without a bridge or better ferry service over the Ashley River, “the turnpike road . . . is comparatively useless.”[18]

Forty-one years after the destruction of its first bridge, the Charleston Bridge Company had paid its debts and amassed sufficient capital to build a replacement structure. The second “new bridge” across the Ashley River to Charleston opened to the public on 15 March 1856.[19] A revised table of toll rates, published two days before the bridge opening, includes a curious stipulation that provokes questions about the daily operation of the turnpike. One half of the published rates of toll, said the company, was “chargeable for the use of the Turnpike Road, without crossing the ferry [or new bridge].”[20] In other words, the Bridge Company acknowledged that persons crossing the bridge always used the turnpike, but persons using the turnpike did not always use the bridge. Travelers on foot, horse, or carriage who used the road but not the bridge received a fifty-percent discount, but the company did not articulate how it collected such reduced tolls. The residence of the company’s solitary “toll receiver” was on the east side of the Ashley River, in the Parish of St. Philip, which travelers in the parish of St. Andrew could only reach by crossing the bridge.[21] I haven’t found any references to a toll-collecting station on the west side of the bridge, or at the western end of the turnpike (where it intersected with Bee’s Ferry Road), so modern travelers are left to ponder this historical conundrum while stuck in traffic.

Confederate soldiers set fire to the second Ashley River bridge as they evacuated Charleston on the evening of 18 February 1865.[22] In the years and decades after that conflagration and the demise of slavery, the proprietors of many old plantations in the Parish of St. Andrew began to divide the land into smaller parcels planted by tenants involved in the business of truck farming. The Charleston Bridge Company survived all these changes, however, and persevered to open a third toll bridge over the Ashley River on 30 January 1886.[23] That structure, built of iron and wood, suffered significant damage during the deadly hurricane of 27 August 1893, but the community’s growing population induced the company to rebuild and reopen the fourth “New Bridge” on 16 June 1894.[24]

The Charleston Bridge Company continued to maintain its privately-owned turnpike across St. Andrew’s Parish after the American Civil War, but its corporate energy and interest in the nine-mile road waned as the nineteenth century drew to a close. Starting in 1890, the company began paving the eastern end of the turnpike with crushed oyster shells, extending just two or three miles westward from the causeway on the west bank of the Ashley River.[25] Few complained about the company’s neglect of the western two-thirds of the road, near its intersection with Bee’s Ferry Road, because the population of that area was too sparse and too poor to arouse corporate action. By the early years of the twentieth century, however, the century-old Bridge Company abandoned any pretense of maintaining its venerable turnpike.

In the spring of 1910, a rising chorus of complaints about the poor state of the shell road in St. Andrew’s Parish, immediately west of the toll bridge, gained community attention through the local newspapers. The affluent members of the new Charleston Automobile Club adopted the road as a special project and pledged to advocate for its improvement. Their conversations with the directors of the Charleston Bridge Company sparked a predictable dispute about who was responsible for the road’s maintenance—Charleston County or the Bridge Company—that soon drew the attention of the county’s legislative delegation and the local Sanitary and Drainage Commission (created in 1900).[26] More surprisingly, however, the Charleston Bridge Company claimed they no longer owned the road in question.

In the early weeks of 1911, a group of citizens in St. Andrew’s Parish petitioned their state representatives to “take steps to determine the title of the road leading into St. Andrew’s Parish from the New Bridge,” which was then “in almost impassable condition.” The petitioners stated that “that neither the county [n]or the Charleston Bridge Company was willing to improve the road,” and this conundrum had plagued local residents “for some time.”[27] A grand jury convened that winter to investigate the state of rural highways in Charleston County reported in February 1911 that the Charleston Bridge Company denied ownership of the old turnpike road in St. Andrew’s Parish. Settlement of its legal status, said the county supervisor, would require an act of the state legislature.[28]

Local representatives took the dispute over the St. Andrew’s Turnpike to the State House in Columbia in the spring of 1911, but that controversy soon faded behind the political scenes and out of public view.[29] The neglected old road west of the Ashley River continued to deteriorate as tensions flared in Europe and the United States’ involvement in the First World War diverted money, resources, and labor to other priorities.[30]

The final act in this long saga commenced in the summer of 1916 with the ratification of the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, the first national highway funding legislation in the United States. This landmark law sparked the creation of a national system of paved roads of a standardized character. By offering large subsidies in the form of 50-50 matching funds, Washington sought to encourage local governments across the nation to initiate road construction and improvement projects. The 1916 highway act also triggered conversations among local, state, and regional authorities about the need for an Atlantic coast highway stretching from Maine to Miami, among many other long-distance routes, that would connect people and commerce across the contiguous United States. The local stretch of the proposed Atlantic coast highway, known as the Charleston-Savannah Highway, came into focus after the conclusion of World War I in November 1918.

In January 1919, as Charleston County was using federal funds to survey various sections of the proposed Charleston-Savannah Highway, the members of the local Sanitary and Drainage Commission pressed the directors of the Charleston Bridge Company to sell their toll bridge over the Ashley River and the rights to their old turnpike. These two assets were crucial components in the creation of the larger Atlantic coast highway, but the parties could not agree on a price.[31] Despite the impasse, the Bridge Company and Charleston County reached an amicable agreement concerning the title to the nine-mile road formerly known as the St. Andrew’s Turnpike. The Bridge Company’s claim that they did not own the road stemmed from an old legal argument rooted in English common law: through long and sustained public use, the private road had simply evolved into a public thoroughfare that belonged to the community.[32]

After continued negotiation and significant repairs to the old “New Bridge” over the Ashley River, the Charleston Bridge Company relented in November 1920. The corporation agreed to sell the bridge, all of its physical assets, and any vestigial rights it might claim in the St. Andrew’s Turnpike to Charleston County for $85,000 worth of bonds funded by federal highway appropriations. The local press rightly noted that the agreement, which would become effective in 1921, “settles for all time the ownership of the highway in St. Andrew’s Parish, but which the county has acquired a right to by virtue of its being opened to travel for so long a period. Whatever rights the Charleston Bridge Company has in this road at the time of the purchase are to be conveyed to the county[,] and all disputes which were likely to arise at the expense of all parties concerned are adjusted by reason of this [sic] county becoming the owners.”[33]

The work of paving the Charleston-Savannah Highway commenced in January 1921 at the east end of the old turnpike, near the west edge of the bridge over the Ashley River. A modern ribbon of concrete covered the old roadbed of sand and oyster shell, though the initial paving was just eighteen feet wide.[34] Six months later, on the first of July, 1921, the Charleston Bridge Company ceded their bridge to Charleston County at a festive public ceremony. The deed was relinquished at noon, the toll was forever removed, and the 110-year-old turnpike officially ceased to exist.[35]

The “New Bridge” constructed in 1894 of wood and iron was outdated by 1921, of course. County officials eager to complete the Charleston-Savannah Highway immediately began planning the funding, design, and construction of a modern replacement bridge over the Ashley River. The new structure, built of concrete and named the Ashley River Memorial Bridge in honor of local servicemen and women who participated in World War One, opened to traffic on 5 May 1926.[36] In November of that year, the federal government adopted the United States highway numbering system that we still use. At the moment, the old St. Andrew’s Turnpike officially became part of U.S. Route 17.

The official end of the toll bridge and turnpike through the rural Parish of St. Andrew in the summer of 1921 marked the beginning of rapid transformation. The area now called West Ashley quickly blossomed into a vibrant suburban landscape populated largely by urbanites fleeing the crowded City of Charleston. As the colonial-era plantations were subdivided into twentieth-century neighborhoods filled with commuters driving automobiles, scores of shops and restaurants appeared along the initial nine-mile stretch of the Charleston-Savannah Highway.

The present high volume of traffic on Savannah Highway, as we now call it, obscures the curious details of its humble roots. The path of the nine-mile turnpike has been widened and modified repeatedly over the generations, but it still follows the remarkably straight line carved across the rural landscape more than two centuries ago. The modern thoroughfare forms a major artery for mobility across Charleston County and continues to evolve with the community it serves. As we consider the transportation needs of future residents, insight from the deep history of Savannah Highway might help pave the way forward.

[1] For more information about the context of Rantowle’s Bridge, see Episode No. 240, “The Stono Rebellion of 1739: Where Did It Begin?”

[2] See Act No. 442, “An Act to empower the several Commissioners of the High Roads, private paths, bridges, creeks, causeys, and cleansing of water-passages, in this Province of South Carolina, to alter and lay out the same, for the more direct and better conveniency of the inhabitants thereof,” ratified on 15 September 1721, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 9 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1841), 49–57.

[3] Petition of Inhabitants or Proprietors of Lands within St. Andrew’s Parish, 1 December 1801, South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Petitions to the General Assembly (series S165015), 1801, No. 107.

[4] SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, no date, No. 1642. The signatures of the petitioners are included therein.

[5] See sections X through XIX of Act No. 1932, “An Act to Establish Certain Roads, Bridges, and Ferries therein Mentioned,” ratified on 17 December 1808, in McCord, Statutes at Large of South Carolina, 9: 434–35.

[6] Charleston Courier, 10 February 1810, page 3, “The Charleston Bridge Company”; Courier, 5 March 1810, page 3, “Charleston Bridge Company”; Courier, 2 July 1810, page 3, “Bridge Festival”; Charleston City Gazette, 3 July 1810, page 2: “Charleston Bridge”; Miller’s Weekly Messenger [Pendleton, S.C.], 4 August 1810; City Gazette, 30 August 1810, “At a Meeting of the Commissioners of the Bridge Company.” The location of the toll house is mentioned in numerous later advertisements and news articles.

[7] Courier, 17 July 1810, page 3, “Communication,” describes the recent work of the Charleston Bridge Company and states “to-day, as I am informed, they begin to run their road to Rantole’s [sic]”; the Bridge Company sought to hire “fifty field hands, to be employed in making their turnpike road in St. Andrew’s Parish,” in Courier, 18 October 1810, page 3, “The Subscriber, in behalf of the Charleston Bridge Company.”

[8] The petition of citizens of St. Andrew’s Parish, 27 November 1844, SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, 1844, No. 113, describes the road as “sixty feet in width and ten miles in length,” while the text of the same petition, printed in Courier, 30 November 1844, page 2, more accurately describes it as “sixty feet in width and nine miles in length.”

[9] The quotation appears in Courier, 17 July 1810, page 3, “Communication.”

[10] Courier, 27 July 1811, page 3, “St. Andrew’s Turnpike Road”; Courier, 21 November 1812, page 3, “Charleston Bridge Company.”

[11] The cost of creating the road is mentioned in the petition of the directors of the Charleston Bridge Company, 30 November 1844, SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, 1844, No. 86.

[12] The lack of compensation for private land usurped by the turnpike road is mentioned in at least two petitions to the state legislature; see the petition of Sophia Chalmers, 10 December 1814, SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly (S165015), 1814, No. 103; and the undated (ca. 1820s) petition of “sundry inhabitants owners of property in the Parish of St. Andrew, SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, no date, No. 5090. See also the story of a lawsuit filed in 1900 by Mrs. Cornelia G. DuPont, heir to Sophia Chalmers, in Charleston Evening Post, 6 June 1900, page 5, “To Cross Bridge Without Toll.”

[13] The undated (ca. 1820s) petition of “sundry inhabitants owners of property in the Parish of St. Andrew, SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, no date, No. 5090, complained of the expense of maintaining “a long line of fencing on each side of the said road.”

[14] Courier, 30 August 1813, page 3, “Dreadful Storm”; City Gazette, 30 August 1813, page 3, “The Gale.”

[15] City Gazette, 26 October 1813, page 3, “Charleston Bridge.”

[16] Courier, 21 October 1814, page 2, “Charleston Bridge Ferry”; see section 15 of Act No. 2072, “An Act to Establish certain Roads, Bridges, and Ferries, therein Mentioned,” ratified on 16 December 1815, in McCord, Statutes at Large of South Carolina, 9: 481–82.

[17] Courier, 21 October 1814, page 2, “Charleston Bridge Ferry. . . For the regulations of the ferry, and the rates of toll, (which are fixed as low as the expences [sic] will admit) apply at the Toll House, to David Ross, Toll Receiver.”

[18] See SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, no date, Nos. 495, 957, 4864. The text of this undated petition also appears in Courier, 22 November 1816, page 2, “Petition to the Legislature.”

[19] Charleston Mercury, 15 March 1856, page 2, “The New Bridge.”

[20] Courier, 13 March 1856, page 2, “Charleston Bridge Company.”

[21] References to the salaried “toll receiver” and his house at the east end of the bridge appear, for example, in Courier, 7 August 1810, page 3, “The Charleston Bridge Company are in want of a Toll Receiver”; Courier, 5 October 1815, page 3, “Wanted, a person properly qualified”; Courier, 15 January 1863, page 3, “Stolen or Taken away by mistake from the Charleston Bridge.”

[22] Courier, 20 February 1865, page 1, “Evacuation of Charleston.”

[23] News and Courier, 20 January 1886, page 2, “Across the Ashley”; News and Courier, 29 January 1886, page 2, “The Ashley River Bridge”; News and Courier, 1 February 1886 (Monday), page 8, “The Opening of the New Bridge.”

[24] News and Courier, 29 August 1893, page 1, “The Wreck of the New Bridge”; News and Courier, 16 June 1894, page 8, “Open for Traffic.”

[25] Charleston News and Courier, 20 October 1890, page 8, “All Around Town,” noted that “the drive over [i.e., west of] the river has been extended about a mile and a half, making the total distance of the shell road beyond the bridge about two miles.” In News and Courier, 27 July 1897, page 8, “A Special Tax Wanted,” a reporter predicted that “the shell road will soon be extended, giving [bicyclists] a three-mile spin in St. Andrew’s Parish.”

[26] News and Courier, 26 May 1910, page 7, letters to the editor: “That Awful St. Andrew’s Road”; News and Courier, 7 June 1910, page 6, “Will Hold Goods Roads Rally”; News and Courier, 29 October 1910, page 10, “Auto Club Re-Elects Officers”; Evening Post, 7 December 1910, page 9, “To Entertain Legislators.”

[27] News and Courier, 5 January 1911, page 5, “Legislators Hold Hearing.”

[28] Evening Post, 24 February 1911, page 9, “The Grand Jury Submits Report”; News and Courier, 25 February 1911, page 3, “Grand Jury Presentment.”

[29] News and Courier, 5 January 1911, page 5, “Legislators Hold Hearing”; Evening Post, 13 January 1911, page 12, “Drainage Board Reports on Work.”

[30] News and Courier, 16 November 1920, page 12, “County of Charleston to Take Over Bridge at the Foot of Spring Street.”

[31] News and Courier, 28 January 1919, page 3, “Tried To Purchase The Ashley Bridge.” The survey work during 1919 is mentioned in Evening Post, 5 February 1920, page 7, “Much Progress by Drainage Board.”

[32] The News and Courier, 16 November 1920, page 12, “County of Charleston to Take Over Bridge at the Foot of Spring Street,” reported that the parties agreed that the “county has acquired a right to [the road] by virtue of its being opened to travel for so long a period.”

[33] Quotation from News and Courier, 16 November 1920, page 12, “County of Charleston to Take Over Bridge at the Foot of Spring Street”; see also Evening Post, 16 November 1920, page 4 (editorial), “Across the Ashley”; Evening Post, 16 November 1920, page 8, “Ashley Bridge Deal Is Closed”; Evening Post, 16 November 1920, page 11, “Admiral Benson Outlines Policy [to the] Shipping Board.”

[34] Evening Post, 25 February 1921, page 6, photo under the heading “Charleston-Savannah, Highway, Federal Aid.” The width of the roadway is mentioned in Evening Post, 5 February 1920, page 7, “Much Progress by Drainage Board.” The starting point of the paving is specified in News and Courier, 16 November 1920, page 12, “County of Charleston to Take Over Bridge at the Foot of Spring Street.”

[35] Evening Post, 1 July 1921, page 1, “Ashley River Bridge Owned By Public Now”; News and Courier, 2 July 1921, page 10, “Ashley Bridge Now County’s Property.”

[36] News and Courier, 5 May 1926, page M5, “Finest Bridge in South is a Paramount Link In Atlantic Coastal Route.”

NEXT: Searching for the Curtain Wall of Charleston's Colonial Waterfront

PREVIOUSLY: The Ghost of Christmas Past: Joy and Fear during the Era of Slavery

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments