The Roots of Spain’s Claim to South Carolina, 1513–1670

Processing Request

Processing Request

The history of South Carolina, like any other chronological narrative, is more than just a list of important events and famous personalities. Our history is a complicated matrix informed by the experiences of numerous people with different and often contrasting perspectives. In honor of National Hispanic Heritage Month, I’d like to draw attention to one of the most significant but perhaps least-remembered perspectives of South Carolina’s early history: The English colony of Carolina was created within the pre-existing boundaries of Spanish Florida, and Spanish officials contested this usurpation for nearly a century.

Like most everyone who went to school in this state the late twentieth century, I learned that the colony of Carolina originally encompassed all of the land situated between Spanish Florida and English Virginia, stretching westward to the Pacific Ocean. That rather general geographic description, variations of which you’ll find in hundreds of English-language books and articles published over the past three centuries, might sound innocuous, but it embodies an important flaw: It represents a biased, Anglocentric perspective of South Carolina’s roots, and stands in contradiction to a very different Spanish view of the same landscape.

I’m not suggesting that the traditional descriptions of the geography of early South Carolina are necessary “wrong,” but simply that they are incomplete. I propose that we gain new insight and improve our understanding of this topic by considering an alternative viewpoint. From the perspective of Spanish history, the large English colony of Carolina was not geographically adjacent to the colony of La Florida, but rather superimposed on top of the northern half of that Spanish territory, which had existed for 150 years before the creation of Carolina. Between 1670 and 1748, generations of Spanish officials complained loudly that the people of South Carolina, and later Georgia, were trespassing on lands rightfully belonging to the crown of Spain. English officials in Charleston and London repeatedly ignored Spanish complaints and persevered through a series of incremental steps to dislodge Spanish colonists from the mainland of North America. By ignoring a controversy that colored so much of South Carolina’s early history, we perpetuate a prejudice rooted in the state’s founding more than three and a half centuries ago.

I’m not suggesting that the traditional descriptions of the geography of early South Carolina are necessary “wrong,” but simply that they are incomplete. I propose that we gain new insight and improve our understanding of this topic by considering an alternative viewpoint. From the perspective of Spanish history, the large English colony of Carolina was not geographically adjacent to the colony of La Florida, but rather superimposed on top of the northern half of that Spanish territory, which had existed for 150 years before the creation of Carolina. Between 1670 and 1748, generations of Spanish officials complained loudly that the people of South Carolina, and later Georgia, were trespassing on lands rightfully belonging to the crown of Spain. English officials in Charleston and London repeatedly ignored Spanish complaints and persevered through a series of incremental steps to dislodge Spanish colonists from the mainland of North America. By ignoring a controversy that colored so much of South Carolina’s early history, we perpetuate a prejudice rooted in the state’s founding more than three and a half centuries ago.

We can encapsulate the complexity of this sprawling topic by posing a deceptively simple question: Where, precisely, on the landscape of late seventeenth century North America did Spanish Florida end and English Carolina begin? The answer depends not so much on the depth of one’s book learning, but on one’s national perspective. The colonies in question included several hundred miles of overlapping territory, the ownership of which was the subject of intense international debate. This lingering dispute was the root of the chronic anxiety that characterized much of South Carolina history from the founding of Charleston in 1670 to the conclusion of the War of Jenkins’ Ear in 1748, and fueled the construction of defensive fortifications during successive waves of heightened tension over a period of a century.

As I’ve explored this topic in recent years, I’ve come to realize that I grew up with a flawed perception of the early relationship between Florida and Carolina. I did not fully appreciate the extent to which early South Carolinians were trespassing on territory claimed by Spain, and I knew little about the deep roots and the long tenure of the Spanish claim to South Carolina. In an effort to help others understand this complex topic, I’ve assembled a pair of programs that cover two and a half centuries of local history. Let’s begin our journey by turning back to the beginning of European exploration of the New World at the dawn of the Age of Discovery.

But first, let’s acknowledge that the land we call South Carolina was not a vacant landscape that was miraculously discovered and then populated by Europeans. In the centuries before the arrival of the first Europeans, the land we now call South Carolina was inhabited by a robust population of indigenous people who possessed their own identities and cultures. The history of those Native American predecessors is certainly an important part of this state’s history, but, with respect, I’d like to defer discussion of that huge topic to future programs. For the purposes of the present conversation, let’s simply acknowledge that the Europeans who came here in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries either ignored or discounted the notion that the indigenous people who had resided here for millennia might have any claim or title to the land. For a host of complex reasons, and through a variety of offensive acts, European explorers and settlers claimed ownership of the land and largely ignored the rights of the indigenous population.

From the Spanish perspective, the first trans-Atlantic voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492 secured for Spain the right to claim the entirety of the New World. According to the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, however, Spain agreed to divide and share the yet-uncharted territories with Portugal. While those two European powers continued their explorations to the south and west of the Caribbean Islands, the King of England sponsored the voyages of John Cabot in the late 1490s to explore the northeastern coast of what we now recognize as the continent of North America. In 1508–9, John’s son, Sebastian Cabot, sailed along the same coastline as far south as Chesapeake Bay.[1]

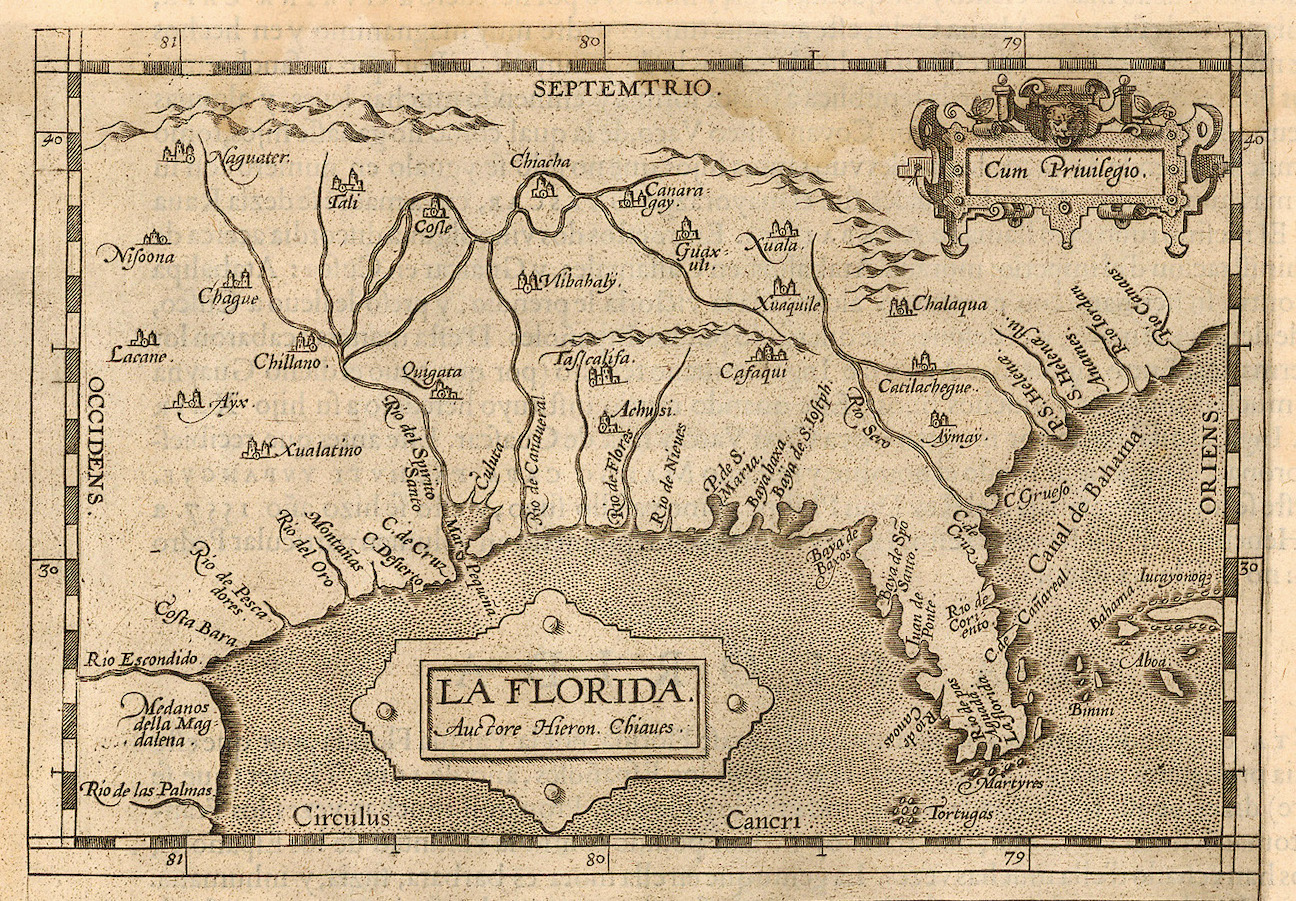

The first documented European expedition to the southeastern coast of North America took place in 1513. In the spring of that year, a small Spanish fleet under Juan Ponce de León sailed from Puerto Rico and landed somewhere along the east coast of the mainland, somewhere north of Cuba. They named the land La Florida and claimed it for the King of Spain, but they had no conception of its geographic boundaries. Over the next sixty-odd years, a succession of Spanish mariners explored and claimed the entire coastline of La Florida, from the southern Keys (around 25 degrees of latitude north of the equator) northward up to and including Cabo Santa María (now Cape Henry, Virginia, around 36 degrees 30 minutes north latitude).

During the remainder of the sixteenth century, numerous Spanish explorers, accompanied by enslaved Africans and Native Americans, crisscrossed the interior of La Florida (including modern Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina). They established the first temporary European settlements within the modern boundaries of the United States, and several of a more enduring nature. A full discussion of the Spanish exploration and settlement of La Florida during the sixteenth century would fill volumes, so, in the interest of pursuing our focus on the contested boundary of South Carolina, I’ll skip ahead to the most salient points.

The Spanish crown claimed the broad territory called La Florida during the first half of the sixteenth century, but five decades passed before the nation established a permanent base on the continent. In the early 1560s, parties of French Protestant adventurers established Charlesfort on Parris Island in what they called Port Royal Sound, in modern Beaufort County, and Fort Caroline in the environs of the modern city of Jacksonville, Florida. Because these French settlements were planted in the central coastline of La Florida, Spanish forces sailed from the Caribbean in 1565 and completely destroyed both incursions. To better defend their territory from future encroachment, Spain finally established a permanent base at San Agustín (now the city of St. Augustine, Florida) in the autumn of 1565.

In the decade following the creation of St. Augustine, Spanish agents established a chain of more than a dozen religious missions along the east coast of La Florida, extending from below St. Augustine to as far north as the harbor of Santa Elena—a place first explored and named by Spanish mariners in August 1526. The Spanish settlement of Santa Elena, clustered around a fort on what is now Parris Island in Beaufort County, was established in 1566 and served as the capital of La Florida for more than twenty years. During those two decades, Spanish forces continued to explore the Atlantic coastline northward into modern North Carolina, then considered the northern frontier of La Florida.

In the decade following the creation of St. Augustine, Spanish agents established a chain of more than a dozen religious missions along the east coast of La Florida, extending from below St. Augustine to as far north as the harbor of Santa Elena—a place first explored and named by Spanish mariners in August 1526. The Spanish settlement of Santa Elena, clustered around a fort on what is now Parris Island in Beaufort County, was established in 1566 and served as the capital of La Florida for more than twenty years. During those two decades, Spanish forces continued to explore the Atlantic coastline northward into modern North Carolina, then considered the northern frontier of La Florida.

During that same era, Queen Elizabeth revived England’s claims to the continent of North America, based on the earlier explorations of John and Sebastian Cabot. The English attempt in 1584 to settle at a place called Roanoke (modern Albemarle Sound, North Carolina) enraged the Spanish, who menaced the area but did not destroy the tentative venture. The English corsair Francis Drake retaliated in 1585 by attacking Spanish ports in the Caribbean, and in 1586 Drake sacked the town of St. Augustine. The destruction caused by Drake’s raids, combined with financial problems back in Spain, induced Spanish officials in La Florida to consolidate their resources. Spanish soldiers withdrew from Santa Elena in 1587 and St. Augustine became the territorial capital of La Florida, but they did not abandon their claim to the colony’s northern reaches. In the succeeding generations, Spanish Floridians nurtured many of the coastal missions located within the modern boundaries of Georgia and maintained a passive foothold at Santa Elena.

Modern audiences might find it odd that Spain was so possessive of La Florida in the sixteenth century, but did not endeavor to fill that territory with settlers like the later English colonies to the northward. But Spain did not view La Florida as a colony for settlement so much as a buffer against foreign influence. The Spanish crown focused most of its energy and resources on its colonies in the Caribbean, Central America, and South America, and valued, above all else, the gold and silver extracted from those territories. This treasure was loaded onto ships and sent back to Spain in large fleets, or flotas, that followed the prevailing ocean currents from the Caribbean Sea to the Straits of Florida, then sailed along the curving coastline of what we now call South and North Carolina, and finally crossed the Atlantic Ocean back to Europe. By preventing other nations from settling within the thousand-mile coastline of La Florida, Spain gained valuable protection for the flotas of priceless treasure sailing from Central America to the mother country.

The English settlement at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 was strategically located immediately north of Spanish Florida, at the southern edge of the coastline that Sebastian Cabot had claimed for England a century earlier. Spanish officials in St. Augustine weren’t happy about the presence of English neighbors in Virginia, but they recognized that land as part of England’s rightful claim on the continent. Two decades later, in 1629, King Charles I of England acted less diplomatically when he granted to Sir Robert Heath a vast tract of land called Carolana, extending from a point just south of the St. John’s River (the modern boundary between Florida and Georgia) to Albemarle Sound in modern North Carolina. This new English province included the entire northern half of Spanish Florida, but Spain took no notice of Carolana because Sir Robert never attempted to settle the land and his grant from the king expired.

The English settlement at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 was strategically located immediately north of Spanish Florida, at the southern edge of the coastline that Sebastian Cabot had claimed for England a century earlier. Spanish officials in St. Augustine weren’t happy about the presence of English neighbors in Virginia, but they recognized that land as part of England’s rightful claim on the continent. Two decades later, in 1629, King Charles I of England acted less diplomatically when he granted to Sir Robert Heath a vast tract of land called Carolana, extending from a point just south of the St. John’s River (the modern boundary between Florida and Georgia) to Albemarle Sound in modern North Carolina. This new English province included the entire northern half of Spanish Florida, but Spain took no notice of Carolana because Sir Robert never attempted to settle the land and his grant from the king expired.

After planting colonies on the continent of North America at Jamestown, Newfoundland, and New Plymouth, English adventurers turned to the Caribbean for new land. In the decade between 1623 and 1632, English men and women began settlements on the islands of St. Kitts, Barbados, Nevis, and Antigua. The Spanish crown resented all of these encroachments, however, and tempers flared as England sought to gain further territory in the West Indies. During the Anglo-Spanish War of 1654–60, English forces seized Jamaica in 1655. Spain fought to regain possession of Jamaica, but the war ground to a halt in 1660 when King Charles II regained the English throne and seemed inclined to make peace with Spain. Sporadic fighting between the English and Spanish in the Caribbean continued during the 1660s, mostly by privateers and buccaneers, while diplomats in Europe tried to settle terms of a lasting peace.

This was the political context in which King Charles II granted the province of Carolina to eight Lords Proprietors in the spring of 1663. The land in question stretched from the southern boundary of Virginia, around 36 degrees north latitude, southward to 31 degrees north latitude (near the modern boundary between Georgia and Florida). In 1665, the king issued a revised charter that extended the southern boundary to 29 degrees north latitude, which encompassed all of the land more than fifty miles south of Spanish St. Augustine. The overlapping territory of English Carolina and Spanish Florida was no accident caused by a poor understanding of the geography in question. Rather, the Carolina grants of 1663 and 1665, made during a period of great tension with Spain, were provocative political gestures. In defiance of the Spanish crown, the English king claimed and granted land that had been recognized for more than 150 years as the northern half of Spanish Florida.

The first English adventurers to settle in Carolina came up from Barbados in 1664 and established Charles Towne on the Cape Fear River in modern North Carolina. That venture dissolved in 1667, but its failure was not the result of Spanish interference. Rather, the Barbadian backers of the settlement on the Cape Fear River returned to the Caribbean because the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–67) threatened the security of Barbados and cut off their much-needed chain of supplies.

The first English adventurers to settle in Carolina came up from Barbados in 1664 and established Charles Towne on the Cape Fear River in modern North Carolina. That venture dissolved in 1667, but its failure was not the result of Spanish interference. Rather, the Barbadian backers of the settlement on the Cape Fear River returned to the Caribbean because the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–67) threatened the security of Barbados and cut off their much-needed chain of supplies.

While English and Spanish diplomats were busy negotiating a treaty to settle their differences in 1669, the Lords Proprietors of Carolina suddenly decided to fund a large-scale expedition to plant settlers in the colony. The timing of this expedition was likely influenced by the peace talks then taking place in London and Madrid, and the Proprietors were determined to have English boots on the ground somewhere in Carolina before a treaty was ratified. The first fleet of settlers sailed from London in late 1669 and headed to Carolina by way of Barbados. The Proprietors instructed them to settle at Port Royal, now the site of Beaufort, South Carolina, but the members of the first fleet were wary about landing in that area so long inhabited by Spain as Santa Elena. Instead, they sailed into the harbor named San Jorge by Spanish explorers more than a century earlier.[2]

The site chosen for the first permanent English settlement in South Carolina in April 1670 reflects the tensions that existed between England and Spain at that moment. The first fleet of settlers did not select a site with the most secure topography, or the most commodious landscape, or the most advantageous vista of the broad natural harbor formed by the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. Rather, they chose a small, low-lying island, surrounded by unhealthy swamp, located behind a larger peninsula so that their settlement would be hidden from the view of any passing Spanish ships. In short, the geographic placement of Charles Towne on the Ashley River in 1670 represents an exercise in stealth. Those early settlers had been sent by the Lords Proprietors, who were empowered by the King of England, but they knew they were trespassing on lands that Spain had jealously guarded for more than a century. The first secretary of South Carolina, Joseph Dalton, acknowledged as much when he wrote to Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper in September 1670: “We are settled in the very chaps of the Spaniards.”[3]

Meanwhile, back in the court of Spain, English and Spanish diplomats signed a formal peace treaty in July 1670 that resolved most of their long-standing grievances in the Caribbean. The text of that document, called the Treaty of Madrid or the Godolphin Treaty, includes a lot of diplomatic verbiage unrelated to South Carolina, but Article VII merits our undivided attention. In that brief paragraph, Spain recognized “that the most Serene King of Great Britain, his heirs and successors, shall have, hold, keep, and enjoy for ever . . . all those lands, regions, islands, colonies, and places whatsoever, being or situated in the West Indies, or in any part of America, which the said King of Great Britain and his subjects do at present hold and possess.”[4]

This brief statement, though devoid of any earth-shattering language, represents a major milestone in the history of Anglo-Spanish relations in North America. In July of 1670, three months after the founding of Charles Towne on the Ashley River, the Spanish crown conceded that England now possessed land that was formerly identified as the northern half of La Florida. The Treaty of Madrid inaugurated a state of general peace between the two nations that lasted for more than thirty years, but it also planted the seeds of discord between Spanish Florida and English Carolina. The 1670 treaty did not articulate a precise boundary line between the two colonies, and this omission engendered contrasting interpretations of the agreement.

From the Spanish perspective, the English settlement at Charles Towne secured England’s claim to the harbor formerly known as San Jorge and all of the territory northward to Virginia, but Spain continued to claim ownership of the land stretching from the Florida Keys to Santa Elena, including what is now called St. Helena Sound in modern Beaufort County. Spanish maps of that era placed the new frontier at 32 degrees, 30 minutes north latitude. To visualize that boundary, imagine a line drawn through Edisto Beach State Park and continuing westward to the Pacific Ocean.[5]

From the Spanish perspective, the English settlement at Charles Towne secured England’s claim to the harbor formerly known as San Jorge and all of the territory northward to Virginia, but Spain continued to claim ownership of the land stretching from the Florida Keys to Santa Elena, including what is now called St. Helena Sound in modern Beaufort County. Spanish maps of that era placed the new frontier at 32 degrees, 30 minutes north latitude. To visualize that boundary, imagine a line drawn through Edisto Beach State Park and continuing westward to the Pacific Ocean.[5]

From the English perspective, however, Spain had no legitimate claim to any of the territory north of the St. John’s River (the modern boundary between Georgia and Florida). The occasional presence of a few Spanish soldiers at Santa Elena and other Spanish missions along the coastline north of St. Augustine during the late seventeenth century did not constitute possession in the eyes of English observers in Charles Towne. Furthermore, the Carolina charters issued by King Charles II in 1663 and 1665 granted them territory down to 31 degrees and then 29 degrees respectively, some 250 miles south of Charles Towne.

The governor of Florida learned of the arrival of English settlers at San Jorge or Charles Towne before he learned about the results of the Treaty of Madrid. He mobilized a fleet in the summer of 1670 to destroy the new English settlement on the Ashley River, but the arrival of a hurricane forced the Spanish ships to retreat to St. Augustine. A smaller expedition in 1671 also failed, and Spanish officials subsequently acknowledged that the English were now permanent neighbors, settled in the environs of modern Charleston County. Floridians continued to hope, however, that the Carolinians would honor the Treaty of Madrid and confine their colonial activities to the lands north of Santa Elena.[6]

But, as we all know, Charleston County is no longer the southernmost part of Carolina. In the decades after the important events of 1670, English-speaking colonists gradually spread southward from the Ashley River and claimed further parts of the territory long identified as La Florida. Spanish officials in St. Augustine resented this encroachment, of course, and occasionally sent forces to harass and destroy the Protestant interlopers.

As a result of these differing interpretations of the 1670 Treaty of Madrid, the people who inhabited South Carolina and Florida during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries lived a state of near constant anxiety. This pervasive tension forms the background of all of South Carolina’s early history, from the arrival of the first European settlers in 1670 to the settlement of a new peace treaty with Spain in the autumn of 1748.

In next week’s program, we’ll explore the Spanish perspective of South Carolina’s southward expansion into the contested territory. While officials in Spain fumed, London bureaucrats feigned ignorance, and the creation of the Georgia colony in 1732 shifted the brunt of Spanish resentment onto a new set of neighbors.

[1] See Evan T. Jones and Margaret M. Condon, Cabot and Bristol’s Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480–1509 (Bristol: University of Bristol, 2016).

[2] Matthew A. Lockhart, “Quitting More Than Port Royal: A Political Interpretation of the Siting and Development of Charles Town, South Carolina, 1660–1680,” Southeastern Geographer 43 (November 2003): 197–212.

[3] Joseph Dalton to Anthony Ashley Cooper, 9 September 1670, in Langdon Cheves, ed., “The Shaftesbury Papers and Other Records Relating to Carolina and the First Settlement on Ashley River Prior to the Year 1676,” in Collections of the South Carolina Historical Society, Volume 5 (Charleston: South Carolina Historical Society, 1897; reprint; Charleston: Tempus Publishing, 2000), 183.

[4] See Article VII of the 1670 Treaty of Madrid in George Chalmers, ed., A Collection of Treaties between Britain and Other Powers, volume 2 (London: John Stockdale, 1790), 37 (emphasis added).

[5] In his 1742 report on the contested border, Antonio de Arrendono repeatedly cited the latitude of 32 degrees 30 minutes as the line of division. See Herbert E. Bolton, ed., Arredondo’s Historical Proof of Spain’s Title to Georgia. A Contribution to the History of One of the Spanish Borderlands (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1925), 113, 125, 140, 144, 146, 149, 153, 154, 187.

[6] See José Miguel Gallardo, ed., “The Spaniards and the English Settlement in Charles Town,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 37 (April, July, October 1936), 49–64; 91–99; 131–41; Verner W. Crane, The Southern Fronter, 1670–1732 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1928), 9–10.

NEXT: Anglo-Spanish Hostility in Early South Carolina, 1670–1748

PREVIOUSLY: Murder and Manhunt in 1820: Albro’s Flight from Slavery, Part 3

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments