The Rise of the Urban Vultures

Processing Request

Processing Request

Today we travel back in Lowcountry natural history to explore a very specific aspect of Charleston’s famous public market, which is the oldest institution of its kind in the United States. Two hundred and ten years ago this August, Charleston’s principal food market in Market Street formally opened to the public. As of the first day of August 1807, all of Charleston’s scattered marketplaces were officially closed, and the new Centre Market, as it was long called, became the daily gathering place for people buying and selling fruit, vegetables, meat, and seafood. A decade ago, back in the summer of 2007, I presented a series of public lectures about this topic, and the Post and Courier published a series of articles drawing attention to the Market’s bicentennial anniversary. Time doesn’t permit a full recital of the convoluted history of early market activity in our city, but a few weeks ago I mentioned a number of the most salient facts in a story about the genesis of Charleston’s Vendue Range.

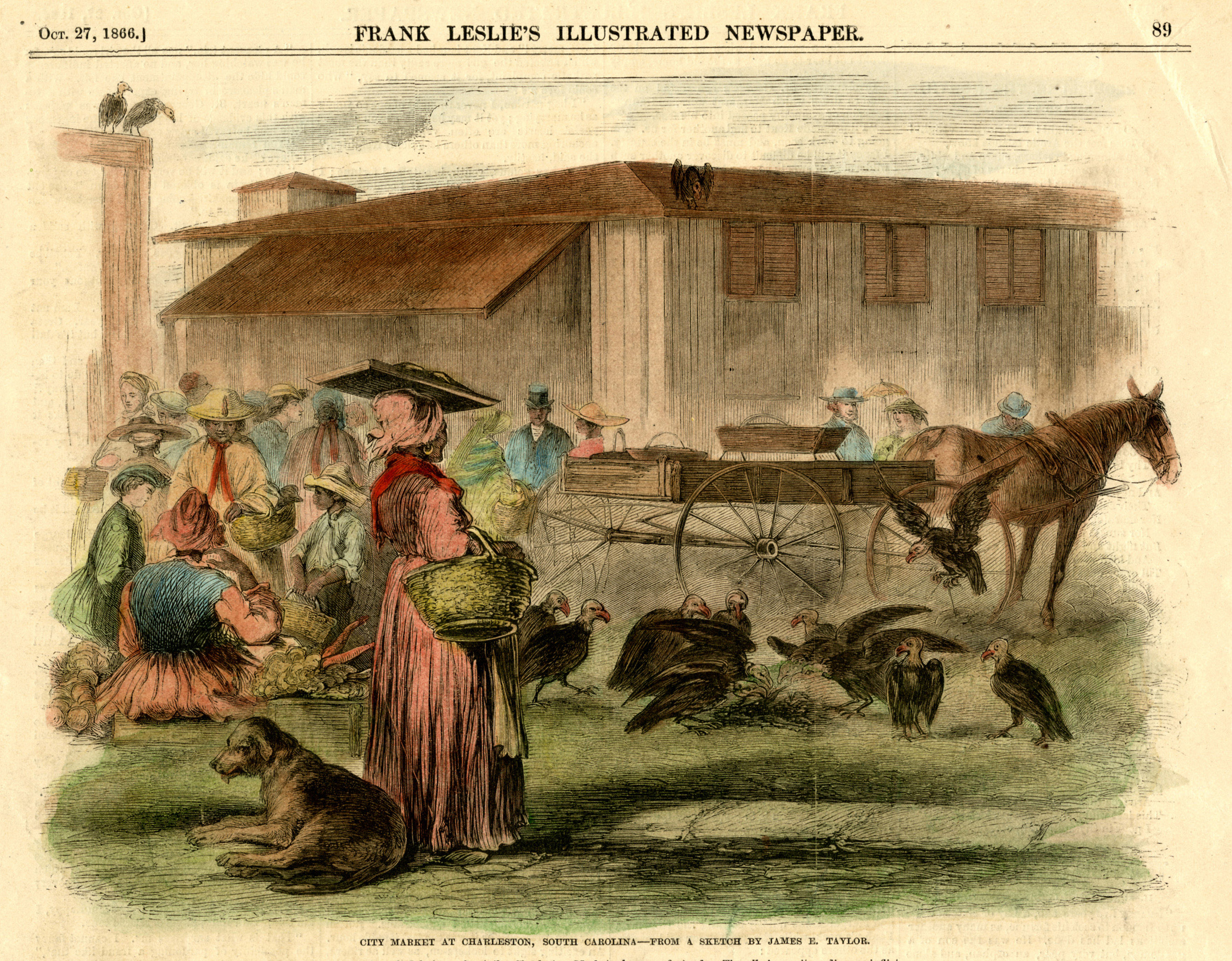

Rather than attempting to condense this vast story, today want to focus on one character that was once a familiar fixture in Centre Market, and whose presence in market lore is often misunderstood today. I’m talking about the black vulture, a scavenging bird that appears in numerous historic descriptions of the market and in countless old photos of the site. In the days before modern refrigeration, and especially in the days before modern sanitation laws, these scavenging birds were daily visitors to the marketplace, where their presence was not only tolerated but protected. You won’t find any vultures in Market Street today because the city expelled the birds in the early years of the twentieth century. Since the urban exodus of these feathered scavengers a century ago, the story of market vultures has become part of the colorful lore of Charleston, complete with a few important inaccuracies. In honor of the 210th anniversary of the Centre Market, let’s travel back to the early days of Charleston and explore the facts surrounding the city’s relationship with the venerable vulture.

First, let’s clear up the common misunderstanding about the identity of the bird in question. Many folks in Charleston refer to the former Market Street scavengers as Turkey Buzzards, and in fact many writers in the nineteenth and early twentieth century used that same name. The red-headed Turkey Buzzard, or more properly, the Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura), is indeed a species found in South Carolina and elsewhere, but it’s not the bird that once frequented our market. More commonly found in the Lowcountry of South Carolina is the black-headed Black Vulture (Coragyps atratus), a large scavenging bird that has been a common sight in urban Charleston since colonial times. They were once so common in the city that locals frequently referred to them, in a half-joking manner, as “Charleston eagles.”

Black Vultures are scavenging birds indigenous to the Lowcountry, so they witnessed the arrival of the first European settlers and enslaved Africans who arrived in South Carolina in the late 1600s. As Charleston grew from a village to a town to a city, vultures lived on the fringes of the human settlement and feasted on our trash and leftovers. A German physician, Johann Schoepf, visiting Charleston in the spring of 1784 made the following observation:

Black Vultures are scavenging birds indigenous to the Lowcountry, so they witnessed the arrival of the first European settlers and enslaved Africans who arrived in South Carolina in the late 1600s. As Charleston grew from a village to a town to a city, vultures lived on the fringes of the human settlement and feasted on our trash and leftovers. A German physician, Johann Schoepf, visiting Charleston in the spring of 1784 made the following observation:

“Nowhere are buzzards to be seen in such numbers as in and about the City of Charleston. Since they live only on carrion, no harm is done [to] them; they eat up what sloth has not removed out of the way, and so have a great part in maintaining cleanliness and keeping off unwholesome vapors from dead beasts and filth. Their sense of smell is keen, as also is their sight; hence nothing goes unremarked of them, that may serve as food, and one sees them everywhere in the streets. There are those who believe that if a buzzard lights upon a house in which an ill man lies, it is a fatal sign for they imagine the bird has wind of the corpse already.”

Dr. Schoepf observed that vultures performed a sort of civic service by removing trash and were therefore tolerated, or at least not molested or discouraged by the human population. In the eighteenth century, however, the vultures weren’t particularly associated with any of the marketplaces of urban Charleston. Before the city government consolidated the sale of vegetables, seafood, and meat in Market Street in 1807, market waste was mostly thrown from the wharves at the east end of Tradd Street and the east end of Queen Street into the Cooper River. From the late 1730s to 1796, the city’s official Beef Market was located away from the water, however, at the northeast corner of Meeting and Broad Streets. Here butchers chopped up the carcasses of animals that had been slaughtered outside the city limits, before being brought by wagons to the Beef Market. So what happened to their meat scraps—did the butchers toss them to the vultures? Apparently not. In all of my extensive reading of early Charleston newspapers, I haven’t come across any complaints or accounts of vultures at the Beef Market, or any other marketplace of eighteenth-century Charleston. Instead, the butchers of early Charleston brought their dogs to the market every day, and the butchers’ dogs kept the market area free of unwanted meat scraps, or offal, as it was usually called.

By the end of the 1790s, however, there were too many dogs in the market, and the dogs occasionally bit each other, horses, and even humans. The spread of rabies was a serious concern at this time, so the job of resolving this situation fell to the Commissioners of the Markets, a group of men appointed by City Council to manage Charleston’s public marketplaces. In 1799 the commissioners banished all dogs, even the butcher’s helpers, from all of the city’s markets. Humans violating this order were subject to a fine of twenty shillings, and their dogs would be killed and “thrown into the stream” (says the Charleston City Gazette of 19 April 1799).

At the turn of the nineteenth century, all of the city’s market activity was briefly concentrated in one crowded spot—the east end of Queen Street, on the Cooper River waterfront. While the city worked to re-establish a market mall in Market Street, scraps from the Queen Street meat market were routinely thrown into the water, where sharks and crabs devoured them. On the first day of August 1807, however, the city opened its new Beef Market in Market Street, a small distance from the water, and the butchers were again landlocked. The animals were still slaughtered outside of town, but the butchers main business was chopping off bits of carcasses to fill customers’ orders. Waste and leftovers were inevitable, but without dogs to snap up the scraps, and without the conveniences of modern garbage collection, how could the city keep the market clean? Enter the black vulture.

Thanks to the descriptions published by several visitors to Charleston in the early nineteenth century, we know that vultures were once a common sight in the city. Englishman John Lambert, for example, stopped in Charleston in January of 1808 during his Travels through Lower Canada and the United States of North America (London: Richard Phillips, 1810). Lambert reported seeing hundreds of turkey buzzards (really black vultures) hovering over the city. Most of the birds were busy picking apart animal carcasses on the northern fringes of the city limits, but some had also followed the scent of dead meat to the new Centre Market in Market street, which had opened just six months earlier. There the vultures performed a public service by “destroying the putrid substances” cast aside by the butchers, and for this reason, Lambert says, “they are not allowed to be killed.” This statement is the earliest known reference to a story that has been repeated hundreds, perhaps thousands of times by later writers and countless tour guides: in earlier times, the vultures of urban Charleston were protected by law; anyone killing or molesting a vulture was subject to a hefty fine. In 1808 John Lambert considered this prohibition to be “extremely improper” because it induced people to laziness and created an unhealthy atmosphere, but the city of Charleston considered it a practical solution. There’s just one problem with this time-honored tale: it’s simply not accurate.

In the colonial era, the provincial government of South Carolina created a number of laws for the regulation of the capital town, Charleston. After the incorporation of the city in August of 1783, our City Council took over the duties of managing the urban settlement on the peninsula. Both the provincial government and the City Council created laws defining market activities in Charleston, but there was never a law protecting the vultures. That said, however, there may have been a market regulation protecting the vultures, but not a law. The difference is more than just a matter of semantics.

All of Charleston’s eighteenth- and nineteenth-century market laws delegated the day-to-day management and operation of the markets to a group of appointed commissioners, the Commissioners of the Markets. By law, the Commissioners of the Markets were empowered to make regulations to control activities in the market places. It’s not unlike the relationship between the U.S. Congress and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission today. Congress passes laws to empower the Commission, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission creates regulations—not laws—for the actual management of nuclear-related activities in our country. The same bureaucratic relationship applied to Charleston’s early markets, so while there was never a law that specifically protected the vultures, it’s likely that the city’s Commissioners of the Markets established a regulation prohibiting people from injuring vultures.

There are no surviving records of Charleston’s early market commissioners, but the wording of numerous newspaper notices published throughout the nineteenth century make it clear that the commissioners routinely passed and amended rules and regulations governing the daily activities in the city’s marketplaces. The market commissioners didn’t personally enforce these regulations, however. Instead, they hired and managed a small staff of salaried “clerks” to patrol the markets and to enforce the rules. One more than one occasion, the texts of nineteenth-century newspaper notices tell us that the market clerks were responsible for making sure the approved market regulations were printed and posted inside the market for all to see. Not one of these printed list of market regulations has survived, but we can imagine what they might have contained. The printed regulations likely included the market’s official hours of operation, prohibitions against dogs and other pets, and other basic policy matters. And here’s where one might find a prohibition against disturbing the vultures. While there is no archival evidence that the vultures were in fact protected by a regulation established by the Commissioners of the Markets, numerous visitors to nineteenth-century Charleston commented on the existence of such a rule.

In 1826, for example, Karl Bernhard, the Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach published an account of his Travels through North America, which includes a description of Charleston’s market. After describing the layout of the sheds in Market Street and the various goods for sale there, Bernhard took notice of the ever-present vultures:

“Upon the roofs of the market houses sat a number of buzzards, who are supported by the offals [i.e., meat leftovers]. It is a species of vulture, black, with a naked head. Seen from a distance they resemble turkeys, for which reason they are denominated turkey-buzzards. They are not only suffered as very useful animals, but there is a fine of five dollars for the killing of one of these birds. A pair of these creatures were so tame that they crept about in the meat market among the feet of the buyers.”

Similarly, in 1831 a correspondent to the New England Magazine (volume 1, pp. 346-50) published a brief description of the “delicious” city of Charleston, which included a mention of the scavenging birds:

“In the vicinity of the market are hundreds of large, sable, bald-headed birds, bearing the respectable compound name of Turkey-Buzzards, and enjoying an exterior particularly grave and solemn. I noted one with a close resemblance to Judge Barleycorn. The buzzard was reconnoitering, from the ridge pole, a shin bone, which he often turned his head to look at alternately with each eye, as I have often seen his Honour turn first one ear and then the other, to the words of the counsel. Nature, however, has furnished him with ears upon a bountiful scale. The buzzards are protected by law, and, in requital, make themselves useful in the capacity of scavengers. Nothing escapes them; they scent their food afar off; and, to say truth, they may be found themselves at some distance in a similar manner.”

(In case you didn’t quite parse that last phrase, this 1831 correspondent was observing that the vultures in Market Street exuded an unpleasant odor.)

Thirty years later, in 1861, a correspondent to the New York Herald (15 December) echoed the Northern fascination with our curious Southern customs:

“In the earlier portions of the day the market has a very busy appearance, the commodious street on either side being crowded with human beings, beasts and birds. To a stranger, from the North particularly, the birds are not the least interesting, they being buzzards, the self-appointed scavengers of warm climates. They are nearly as large as a turkey, and are tame, familiar and grotesque to the last degree. They surround the market, particularly at the closing in the afternoon, when everything not sold must be cleared out, hopping and skipping in the street and on the sidewalks in a manner peculiarly their own, or roosting on all the eaves and chimney tops when they have gorged themselves, or there is nothing more for them to eat. They are looked upon by the inhabitants as a necessary evil, and are protected by law.”

In 1870, an agent of the South Carolina [Agricultural] Institute published an even more intimate description of the familiar bird. The anonymous narrator of a walking tour of urban Charleston offered the following advice to anyone venturing down Market Street:

“If he visits the market in the daytime, he will be sure to become acquainted with the Charleston Eagle. This melancholy bird, vulgarly called a buzzard, is one of the peculiar institutions of our beloved metropolis, that deserves a passing notice at our hands. The headquarters of the eagle are in Market street, in the neighborhood of the butchers’ temple, and there, of a fine morning, he may be seen in all his glory, flying, flapping, moping, standing, fighting, stealing, walking, sailing, running. This eagle is a sombre [sic] bird, dark of hue, gloomy in countenance, and remarkably taciturn—a voiceless bird, that flies without a song and eats without a quack. So far this eagle is respectable—gravity is dignity, silence is wisdom. But, alas! for his respectability, the Charleston eagle is a glutton. The race to which he belongs are winged hyenas, they scent corpses from afar; but our bird has become, by habit and education, simply a glutton, gorging himself on refuse meat which is not yet putrid. He might prefer his food a little more game, if allowed to indulge in the natural idiosyncracies [sic] of his appetite, but he meets with much competition in the eating business, and he must swallow his food quickly or not at all. Where his respectability ends, however, his utility begins, and in this he resembles many an unfeathered biped who makes his living by doing the dirty work of life. Our eagle might flap his sombre [sic] wings and shake his melancholy head with the unction of a parson and wandering brickbat, mischievous arrow, or idle ball; but fortunately for his comfort and his safety he can eat dirt, for which quality he was promoted by our sage forefathers to the position of scavenger, and presented with the freedom of the city, and with a perpetual insurance on his life. He thus belongs to a privileged class that has not been abolished by the rump Congress, and, like other aristocrats, he sometimes puts on airs and abuses his franchise. He has been known to steal meat from a market-basket, and to make frequent raids upon the butchers’ stalls, and yet these trespasses were committed with impunity, the law protecting his life by penalty of five dollars. When carried away by the passion of gluttony, his breaches of the peace are frequent, and in fact so notorious, that they have been celebrated by an old poet in the following verses:

‘A gallant sight it is, to see / The Buzzards in their glory, / Fall out about an old beef knee / And fight till they are gory!’”

The aforementioned eyewitness descriptions of Charleston’s market and its scavenging vultures are both illuminating and entertaining, and there are more out there in various archival sources, but I don’t want to belabor the main point of this conversation: black vultures were an omnipresent part of life in urban Charleston from the earliest days of the town. The city formed a special relationship with the birds in the early nineteenth century, shortly after the opening of the new Centre Market in Market Street in August 1807. Owing the birds’ natural attraction to the animal flesh discard by humans, vultures became the market’s sanctioned and protected clean-up crew. It was an odd relationship, to be sure, but one that the city government apparently tolerated and endorsed. As the years passed, however, and ideas about hygiene and public health evolved, attitudes about the scavenging birds began to change. By the 1880s, the relatively new science of bacteriology was gaining acceptance, and the familiar vultures were increasing viewed as pests.

Today I’ve given you a brief description of the rise of the vultures in the Charleston market, but the disappearance of the birds from Market Street is, in my opinion, an equally interesting tale. I’m out of time for this week, so tune to the Charleston Time Machine next week for the conclusion of the dramatic, pathetic, and intriguing story of the fall of Charleston’s urban vultures.

NEXT: The Fall of the Urban Vultures

PREVIOUSLY: Huzzah For Bastille Day?

See more from Charleston Time Machine