The Rise of Charleston’s Horn Work, Part 2

Processing Request

Processing Request

Over a period of nearly a year and a half in the late 1750s, the people of Charleston watched scores of laborers transform tons of oyster shells into a towering concrete barrier designed to protect the town’s northern boundary from invading enemies. Its construction was deemed vitally important in 1757, but the changing tide of world events convinced local authorities to abandon the tabby Horn Work before it was even finished. This turbulent genesis forms a long-forgotten prelude to the gallant defense of South Carolina’s capital during the American Revolution.

Let’s begin with a brief review of last’s week’s program. In mid-June 1757, during the early stages of the Seven Years’ War with France, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Bouquet came to Charleston with five companies of the British 60th Regiment of Foot (the “Royal Americans”). New defensive fortifications were then underway at White Point, at the town’s southern tip, but Bouquet convinced the South Carolina provincial government to construct a new fortified gate to defend the back or north side of the capital town. Lieutenant Emanuel Hess, an engineer with the 60th Regiment, drew a plan for a horn work composed principally of oyster shell concrete (tabby), with a narrow gate straddling the Broad Path (King Street) leading into Charleston. Governor William Henry Lyttelton approved Hess’s plan in late August, and planning commenced. In mid-October, Lt. Col. Bouquet and Lt. Col. Archibald Montgomery of the newly-arrived 62nd Regiment offered for some of their men to labor on the Horn Work. In early November, the South Carolina Commissioners of Fortifications acquired a rectangular tract of fifteen acres necessary for the new town gate, located just beyond the northern boundary of urban Charleston, and selected three of their own board members to personally superintend the project. The commissioners then directed one hundred soldiers, equipped with a sufficient number of wheelbarrows and spades, to begin digging the foundations of the Horn Work on the morning of Monday, November 14th.

Beginning Construction:

During the initial weeks of labor in late 1757, the superintendents and soldiers apparently cleared the site of trees and obstructions, laid out the lines of the Horn Work on the ground, and then began to dig trenches for its foundations. The surviving records of this work do not mention the presence of Lieutenant Hess, but he likely attended and directed the effort in some capacity. As this preliminary work neared a conclusion in late December, the Commissioners of Fortifications hired Thomas Gordon, a well-known local bricklayer, to “conduct” the tabby work both in Charleston as well as at the new powder magazine in Dorchester, twenty miles away. To facilitate his dual management duties, the commissioners agreed to pay Gordon the large sum of £125 (South Carolina currency) per month on condition that he agreed “to furnish one man in Charles Town & another in Dorchester in his absence & himself to go from one to the other as he shall find it necessary.”[1]

During the initial weeks of labor in late 1757, the superintendents and soldiers apparently cleared the site of trees and obstructions, laid out the lines of the Horn Work on the ground, and then began to dig trenches for its foundations. The surviving records of this work do not mention the presence of Lieutenant Hess, but he likely attended and directed the effort in some capacity. As this preliminary work neared a conclusion in late December, the Commissioners of Fortifications hired Thomas Gordon, a well-known local bricklayer, to “conduct” the tabby work both in Charleston as well as at the new powder magazine in Dorchester, twenty miles away. To facilitate his dual management duties, the commissioners agreed to pay Gordon the large sum of £125 (South Carolina currency) per month on condition that he agreed “to furnish one man in Charles Town & another in Dorchester in his absence & himself to go from one to the other as he shall find it necessary.”[1]

To direct the enslaved laborers who would soon join the hired soldiers, the commissioners employed John Holmes to act as “overseer” or foreman of the work “on the North Line.” In addition, Holmes brought his son and another “white lad” to the site to act as his assistants, brought his own “Negro carpenter,” and included his own “boat & Negroes” in the bargain. For the duration of the Horn Work construction, from late December 1757 to the end of March 1759, Thomas Gordon periodically supervised the tabby work while John Holmes managed the daily labor force, the delivery of materials, and the job site in general.[2]

A large spike in payments for both labor and rum in early 1758 suggests that far more than one hundred British soldiers might have worked on the Horn Work during the first two months of that year, but the details are now lost. The labor agreement of October 1757 required the soldiers to work just six hours (half a day’s labor in the eighteenth century), so it’s possible that there were two shifts of one hundred soldiers working each day. Many continued laboring on Charleston’s “north line” until early March and others perhaps until early May, when the regiments under the command of Lt. Cols. Bouquet and Montgomery, respectively, boarded transport vessels that returned them to the northern colonies. Because the local government had agreed to provide every soldier with a gill of rum (a quarter of a pint) for each day’s work, the Commissioners of Fortifications paid for a total of ten hogsheads of rum (630 gallons) during their relatively brief term of service on the Horn Work.[3]

As a member of the Royal American regiment, Lieutenant Emanuel Hess was destined to depart Charleston with Lt. Col. Bouquet and the rest of the officers under his command. Before they set sail that spring, however, Governor Lyttelton advised the South Carolina legislature to consider rewarding the young engineer with “a proper recompense” for having “perform’d much good service in planning & directing the construction of the fortifications.” The governor also suggested they might offer Hess “a suitable allowance to make it worth his while to remain here,” but apparently the engineer could not be swayed. At his departure from Charleston in late March 1758, the commissioners authorized a payment of £1100.7.6 (South Carolina currency), representing approximately thirty-seven weeks of work at the rate of £30 a week.[4]

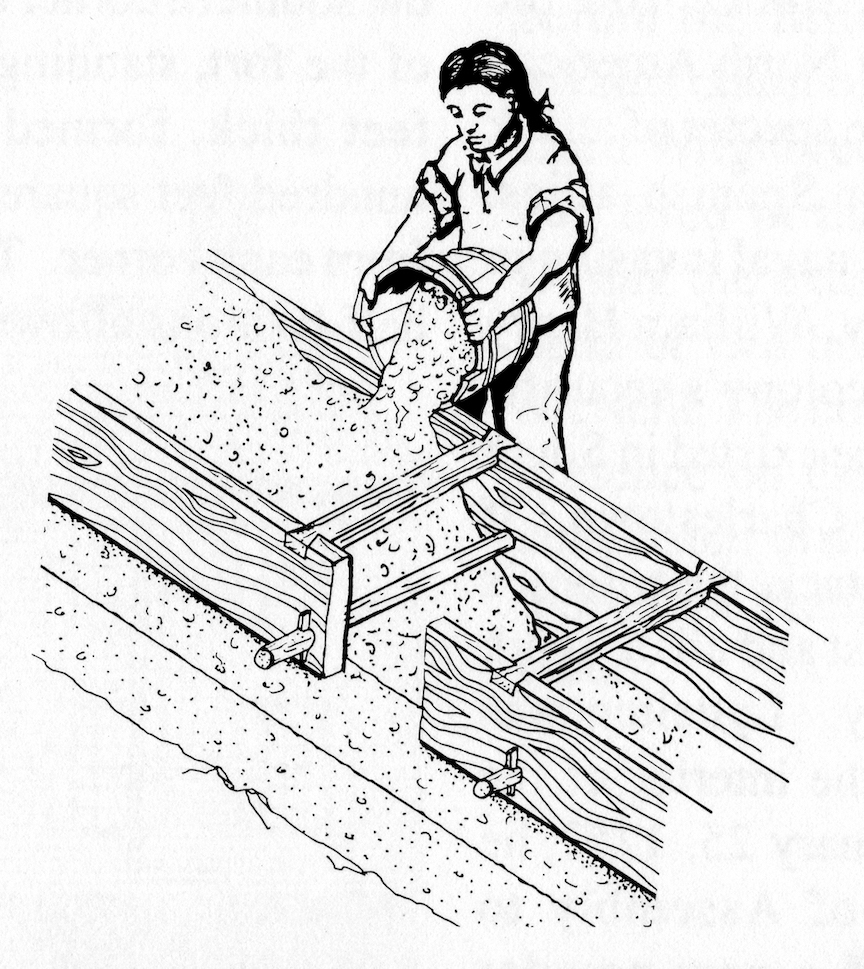

The surviving records of the Commissioners of Fortifications provide few details related to the progress of the Horn Work in 1758 and identify only a fraction of the men who labored on that project. Early in its construction, for example, the commissioners paid Peter Tamplatt and William Hall in separate accounts “for carpenter’s work on the North Works.”[5] The records do not specify the nature of their respective efforts, but they were probably supplying wooden forms or boxes used to shape the tabby mixture as it was poured. Later carpenters—free or enslaved—undoubtedly erected scaffolding as the walls grew above head height. To transport various materials to the job site, the commissioners purchased a sturdy wooden cart and at least two horses.[6] In the eighteen months between October 1757 and March 1759, the Commissioners of Fortifications purchased more than five hundred wheelbarrows from several local carpenters for the use of the laborers at both White Point and the Horn Work.[7]

Determining in the size of the enslaved labor force used to build the Horn Work is a task made difficult by the accounting methods used by the clerk of the Commissioners of Fortifications, but it’s possible to extrapolate some reasonable estimates. Between September 1755 and May 1759, the clerk recorded a series of monthly bulk payments for laborers employed on the fortifications of urban Charleston. Those payments rendered between December 1757 and April 1759 include monies for both the Horn Work and White Point combined into one sum. On just one occasion, in August 1758, the clerk separated the labor costs for each of the two projects. Of the approximately 203 enslaved men working on the fortifications that July, fifty-six, or slightly less than one-third the total number, were employed at the Horn Work. If we extrapolate this ratio to the rest of the construction calendar, we can estimate that between fifty and eighty enslaved men labored alongside the overseers and tradesmen at the Horn Work each month from January 1758 through early November of that year. Following a reduction of expenses in mid-November, the work was continued by a gang of twenty to thirty men through the end of March 1759.[8]

Oyster shells and the lime derived therefrom formed the principal ingredients of Charleston’s tabby Horn Work, but the surviving records of its construction provide very little information about the quantity of shells used to form its walls. The extant journal of the Commissioners of Fortifications, for example, notes the delivery of just 18,000 bushels of shells to the Horn Work, while the total quantity required for its construction was undoubtedly much higher. Similarly, just two contractors received payments for delivering lime to that job site a few occasions.[9] Rather than suggesting clerical neglect, the sparse documentation of these necessary materials appears to stem from cost-saving measures implemented by the commissioners at the outset of the project.

Oyster shells and the lime derived therefrom formed the principal ingredients of Charleston’s tabby Horn Work, but the surviving records of its construction provide very little information about the quantity of shells used to form its walls. The extant journal of the Commissioners of Fortifications, for example, notes the delivery of just 18,000 bushels of shells to the Horn Work, while the total quantity required for its construction was undoubtedly much higher. Similarly, just two contractors received payments for delivering lime to that job site a few occasions.[9] Rather than suggesting clerical neglect, the sparse documentation of these necessary materials appears to stem from cost-saving measures implemented by the commissioners at the outset of the project.

In mid-October 1757, just before the Horn Work project got underway, the Commissioners of Fortifications advertised their desire to receive immediately a large quantity of lime from local suppliers, for which they were prepared to pay “upon delivery on the works in Charles Town.” These initial supplies of lime at the job site might have been sufficient to sustain the tabby construction for several months. In the final weeks of 1757, the commissioners also purchased two pettiaugers (large sloop-rigged rowboats) manned by hired enslaved mariners, as well as two schooners commanded by hired white “patroons” and crewed by enslaved men.[10] The surviving records never clearly articulate the purpose of these four vessels, but the commissioners apparently intended their crews to gather oyster shells from nearby waters and deliver them directly to the laborers working at the Horn Work, White Point, and Fort Johnson on James Island. Some of those oysters were likely roasted and consumed by the workers before transforming the shells into tabby, and some of the shells might have been burned at or near the job site to produce the necessary lime.[11]

The Commissioners of Fortifications nearly described these customary practices in the summer of 1758 when they sought to curtail expenses. On June 15th, the commissioners informed Captain Robert Williams, then superintending tabby work at Fort Johnson, that funds for his project were running low. From that time he was “to keep only so many hands as will be necessary” to “work up the materials he has now on hand” and “for [the] making of lime for the works in Charles Town.” In the weeks and months that followed, Williams continued to produce lime for the Horn Work and to use the government-owned vessels to transport it across the harbor.[12]

One month later, the commissioners decided that they were paying too much for shells—and not always receiving the full measure—when they had occasion to purchase bulk quantities from private parties. On July 24th, 1758, they resolved to purchase no more shells and henceforth to rely solely on those supplied by the enslaved men working in the government-owned boats.[13] In short, there was little occasion to measure and count the volume of incoming oyster shells because the government generally did not pay for them. The foremen supervising the work simply deployed enslaved mariners to fetch from local waterways whatever quantity they required.

Designing the Gateway:

A year after the initial conversations about the need for a Horn Work to defend the northern approach to Charleston, the Commissioners of Fortifications met with Governor Lyttelton to review the progress of the town’s ongoing defensive works. On July 21st, 1758, the commissioners laid before the governor their accounts documenting payments to various tradesmen, managers, suppliers, and laborers. The governor was apparently pleased by their administrative efforts and continued to regard the various fortification projects across the South Carolina Lowcountry as necessary for public safety. Before concluding their meeting, the assembled gentlemen agreed “that the Horn Work at the north end of the town be constructed and compleated [sic] with the utmost expedition.”[14]

A year after the initial conversations about the need for a Horn Work to defend the northern approach to Charleston, the Commissioners of Fortifications met with Governor Lyttelton to review the progress of the town’s ongoing defensive works. On July 21st, 1758, the commissioners laid before the governor their accounts documenting payments to various tradesmen, managers, suppliers, and laborers. The governor was apparently pleased by their administrative efforts and continued to regard the various fortification projects across the South Carolina Lowcountry as necessary for public safety. Before concluding their meeting, the assembled gentlemen agreed “that the Horn Work at the north end of the town be constructed and compleated [sic] with the utmost expedition.”[14]

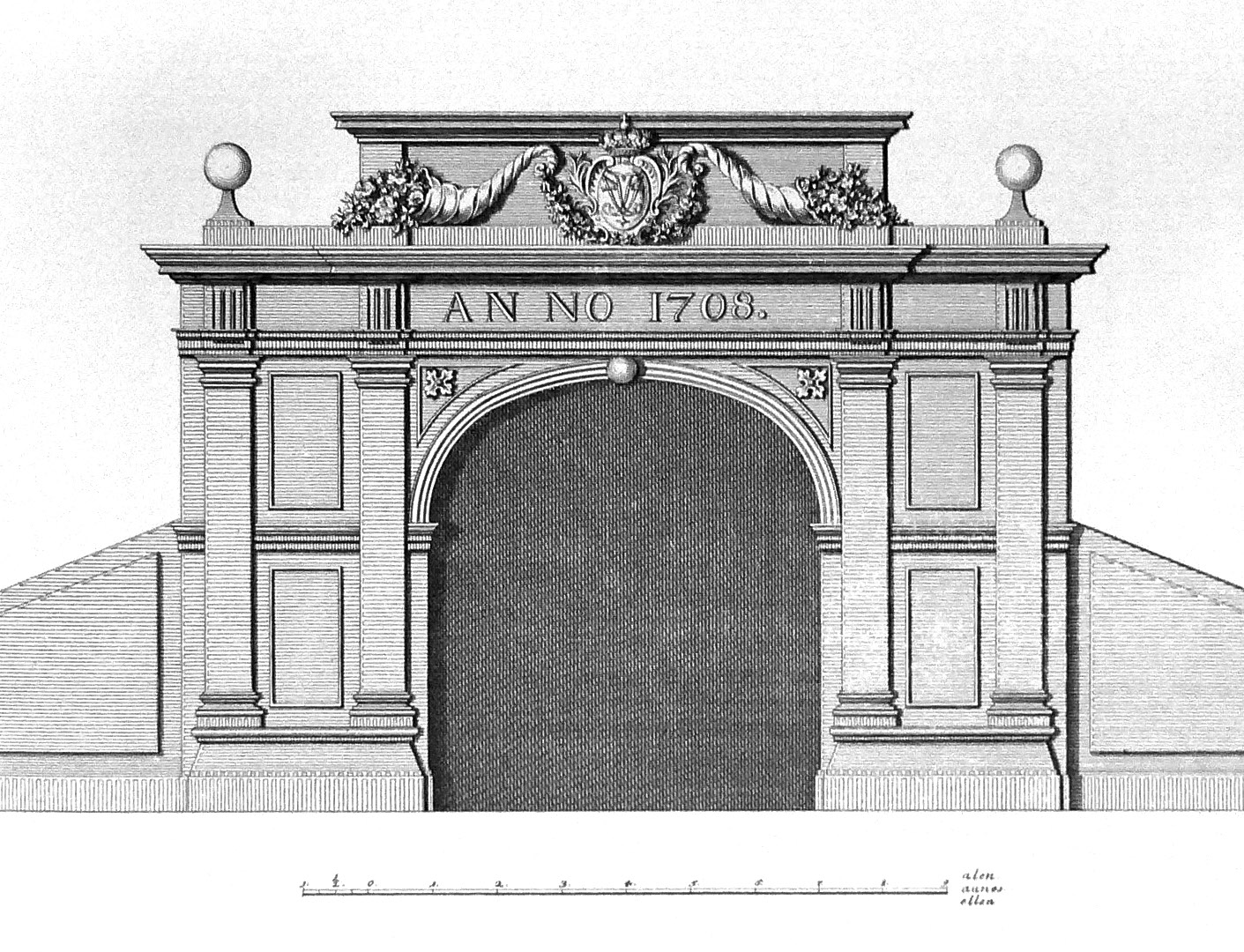

Nearly ten months after laborers commenced digging the foundation trenches of the Horn Work, its central curtain wall straddling the Broad Path (King Street) was apparently at or near a state of completion. Lieutenant Hess’s plan for this structure, which is now lost, apparently included a simple, unremarkable opening in the curtain wall to permit the flow of traffic in and out of Charleston. At least one member of the community objected to this simplicity, however, and sought to add distinction and prestige to the gateway into the capital of South Carolina. George Roupell, one of the Commissioners of Fortifications, was also known as a gentleman amateur with a talent for illustration. On September 7th, 1758, the commissioners’ clerk noted that “Mr. Roupell laid before this board a plan of a Gateway at the entrance into town through the Horn Work.” No copy or description of his illustrated plan is known to survive, but we might imagine that it was likely inspired by the neo-Classical architectural style then fashionable in both London and Charleston. Whatever its attributes or dimensions might have been, we know that the gentlemen of the board approved its design. The clerk recorded simply that the commissioners agreed to Mr. Roupell’s proposal, which they “ordered to be carried into execution.”[15]

The fact that the plan of the gateway was distinct from the plan for the rest of the Horn Work suggests that it included some features that were intentionally more ornamental than functional. Such a design would have been in keeping with a long tradition of decorative gateways attached to hundreds of defensive works built around the world from ancient times to the recent past. To emphasize the contrast with the surrounding tabby walls, George Roupell’s design might have incorporated locally-produced red bricks (commonly seen in colonial-era local construction), perhaps rendered in stucco and rough-cast to resemble stone. This possibility is strengthened by the fact that Thomas Gordon, the contractor supervising the tabby construction, received payment for both “brick work & attending the tappy work at the Horn Works” in the spring of 1759.[16]

The surviving physical remnants of the Horn Work foundation indicate that the curtain wall on the structure’s north side measured approximately three hundred and thirty feet (five chain, or one hundred meters) across, but the breadth of the opening forming the gateway is currently unknown. (It is possible, however, that some trace of it remains under the modern roadbed in the center of King Street.) Part of the general purpose of a horn work was to control the flow of traffic in and out of the town, so we can imagine that Mr. Roupell’s design did not provide a generous amount of access through Charleston’s gateway. Contemporary advice on the construction of fortified gates recommended a passageway just ten feet wide, or perhaps a bit more depending on the scale of the works in question. That recommendation might have prevailed in Charleston. On several occasions in the early 1770s, local grand juries complained that the narrowness of the passageway leading through the Horn Work was a constant source of frustration to travelers. Based on all of these facts, we might conclude that width of the passage was probably no more than ten or twelve feet across.[17]

Determining the height of the gateway is now a matter of some conjecture. The passageways through most horn works in Europe were framed by relatively simple pillars and generally lacked a covering or horizontal element.[18] As a relatively low “outwork” on the fringes of a fortified town, a textbook horn work was considered less important than the taller and more formal gate located within the town itself. Charleston had no other entrance gate in the 1750s, however, and George Roupell apparently felt the need to amend Emanuel Hess’s original design for this feature. It seems likely that he sought to create a visual frame for the intersection of tabby fort and sandy road, like a proscenium arch straddling a theatrical stage. We don’t know the height of the Horn Work’s northern curtain wall, but, for the sake of argument, we might conjecture that it stood approximately ten to twelve feet above the roadbed. Such a height would have created a square passageway, so I believe Roupell’s design probably extended slightly above the walls to create an upright rectangle that added visual distinction to the form. Rather than using a simple post-and-lintel construction to frame the town gateway, Mr. Roupell’s design likely included a variety of familiar neo-Classical elements such as pilasters, quoins, voussoirs, and some sort of arched or triangular pediment.

Determining the height of the gateway is now a matter of some conjecture. The passageways through most horn works in Europe were framed by relatively simple pillars and generally lacked a covering or horizontal element.[18] As a relatively low “outwork” on the fringes of a fortified town, a textbook horn work was considered less important than the taller and more formal gate located within the town itself. Charleston had no other entrance gate in the 1750s, however, and George Roupell apparently felt the need to amend Emanuel Hess’s original design for this feature. It seems likely that he sought to create a visual frame for the intersection of tabby fort and sandy road, like a proscenium arch straddling a theatrical stage. We don’t know the height of the Horn Work’s northern curtain wall, but, for the sake of argument, we might conjecture that it stood approximately ten to twelve feet above the roadbed. Such a height would have created a square passageway, so I believe Roupell’s design probably extended slightly above the walls to create an upright rectangle that added visual distinction to the form. Rather than using a simple post-and-lintel construction to frame the town gateway, Mr. Roupell’s design likely included a variety of familiar neo-Classical elements such as pilasters, quoins, voussoirs, and some sort of arched or triangular pediment.

A pair of contemporary accounts seem to confirm that Charleston’s Horn Work included some sort of horizontal structure across the uppermost part of the gateway at least ten feet above the surface of the road. In his Memoirs of the American Revolution, General William Moultrie recalled galloping on horseback “through the gate” of the Horn Work as British soldiers approached Charleston in May 1779. One year later, on May 12th, 1780, Captain Johann Hinrichs recorded in his diary of the siege of Charleston that the British troops marching into the town passed “under the gate” of the Horn Work. From these descriptions, we can conclude that some sort of elevated horizontal feature bridged the opening of the gateway, and that horizontal feature was sufficiently high for a man on horseback to gallop underneath it.[19]

A Change of Pace:

On September 21st, 1758, after more than a year of near constant activity, the Commissioners of Fortification observed that the pace of their work was slowing. They agreed to meet henceforth only twice a month, “as the business is less[e]ned.” The dwindling state of their funds no doubt played some part in reducing the flurry of construction around Charleston, but there were other, more distant factors that probably contributed to that change. In late July, British forces defeated a stubborn French defense of Louisbourg fortress on Cape Breton Island. In late August, British troops captured Fort Frontenac near Lake Ontario. News of these victories in the autumn of 1758 brought elation to the British subjects in South Carolina, as did news that British forces, including the 60th Regiment of Royal Americans, had captured the important French outpost at Fort Duquesne (now Pittsburgh) in late November. The tide of the war had clearly turned in Britain’s favor. The idea of French soldiers or sailors mounting a sophisticated assault anywhere along the southern coastline now became an increasingly remote possibility. At the same time, increasing disaffection among the Cherokee people on the western frontier soon drew South Carolina’s provincial government into an unexpected war with a long-time ally (see Episode No. 100).

On November 9th, 1758, the Commissioners of Fortifications agreed “to discharge all the boats on hire and lay up the two schooners” bringing shells and lime to the construction projects at White Point and the Horn Work. At the same time, they resolved to discharge all the laborers working on those projects, with the exception of a few hands at White Point and “except those employed in finishing the Gateway thro’ the Horn Work.” In early December, Governor Lyttelton assented to the sale of the two schooners and several horses that had been “bought some time ago for the use of the fortifications which are now of little or no use.”[20] On February 15th, 1759, the commissioners ordered John Holmes, overseer of the laborers at the Horn Work, “not to receive any more lime upon or for the use of the works now under your oversight.”[21] Finally, on March 28th, the commissioners agreed to discharge Mr. Holmes, “the overseer & Negroes on the Horn Work on Saturday next” (March 31st), and ordered Holmes to “secure all the tools &ca. belonging to the said work in the store [at White Point] & deliver an account of the same to the clerk of this board.”[22]

On November 9th, 1758, the Commissioners of Fortifications agreed “to discharge all the boats on hire and lay up the two schooners” bringing shells and lime to the construction projects at White Point and the Horn Work. At the same time, they resolved to discharge all the laborers working on those projects, with the exception of a few hands at White Point and “except those employed in finishing the Gateway thro’ the Horn Work.” In early December, Governor Lyttelton assented to the sale of the two schooners and several horses that had been “bought some time ago for the use of the fortifications which are now of little or no use.”[20] On February 15th, 1759, the commissioners ordered John Holmes, overseer of the laborers at the Horn Work, “not to receive any more lime upon or for the use of the works now under your oversight.”[21] Finally, on March 28th, the commissioners agreed to discharge Mr. Holmes, “the overseer & Negroes on the Horn Work on Saturday next” (March 31st), and ordered Holmes to “secure all the tools &ca. belonging to the said work in the store [at White Point] & deliver an account of the same to the clerk of this board.”[22]

As the last workers collected their tools and prepared to quit the unfinished Horn Work in the spring of 1759, they might have reflected on the speed with which that structure had become obsolete. A broad new fortress to defend the northern entrance to Charleston had seemed so vitally important during the summer of 1757, but the events of less than two years’ time had rendered that structure utterly unnecessary, not even worthy of completion. The expenditure of more than £10,000 (S.C. currency) of local tax revenue had produced a towering mass of tabby and brick, stretching nearly seven hundred feet (over 200 meters) from east to west, that succeeded only in congesting the flow of traffic in and out of the provincial capital. South Carolina’s attentions turned to the bloody Cherokee frontier in the autumn of 1759. Further British victories at Quebec in September 1759 and at Montreal in September 1760 finally obliterated fears of French incursions into the Southern colonies. Peace formally arrived in 1763.[23]

Epilogue:

After Lieutenant Hess sailed with his regiment from Charleston to Philadelphia in the spring of 1758, he joined General John Forbes on an expedition to dislodge French troops from Fort Duquesne at the forks of the Ohio River (now Pittsburgh). Hess never actively participated in that mission, however, as he was already sick when he arrived in Philadelphia. General Forbes sought Hess’s professional advice that June but noted that the lieutenant was “dying of a deep consumption.” Despite his failing health, Hess soldiered westward with his regiment to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he became too ill to continue. “I fear that I must give up all hope of making this campaign,” he wrote on September 20th, “and should even thank the almighty if he will restore me to health for the next one. My lungs are affected and the doctors, judging by the symptoms, find that the disease is already incurable.” The British expedition led by General Forbes, which included Brevet Brigadier General George Washington, accomplished its mission by capturing Fort Duquesne in late November 1758. But Lieutenant Hess was not present among the victors. He died at Lancaster on February 22nd, 1759, and was buried the next day “with all military honors and a great deal of economy.”[24]

The various fortifications in South Carolina designed by Emanuel Hess and other men during the turbulent 1750s were largely abandoned in the peaceful 1760s. The Horn Work guarded the northern entrance into Charleston during the American Revolution and until 1784, during which time some locals described it as the old “royal works.” The origin of that name is unclear, but I can think of at least two possibilities. It might stem from the fact that it was the only fortification in Charleston designed by a member of the royal army, and for which members of the royal army participated in its construction. Alternatively, it’s possible that George Roupell’s design for the gateway of the Horn Work included Britain’s royal coat of arms in some form. In either case, it’s especially ironic that this “royal work” later served as the citadel for an army of American rebels fighting to repel a royal siege. After nearly twenty years of neglect, the Horn Work was revitalized in the late 1770s to play an important role during the American Revolution. In a manner of speaking, it lived on to fight another day, and its story continues.

The various fortifications in South Carolina designed by Emanuel Hess and other men during the turbulent 1750s were largely abandoned in the peaceful 1760s. The Horn Work guarded the northern entrance into Charleston during the American Revolution and until 1784, during which time some locals described it as the old “royal works.” The origin of that name is unclear, but I can think of at least two possibilities. It might stem from the fact that it was the only fortification in Charleston designed by a member of the royal army, and for which members of the royal army participated in its construction. Alternatively, it’s possible that George Roupell’s design for the gateway of the Horn Work included Britain’s royal coat of arms in some form. In either case, it’s especially ironic that this “royal work” later served as the citadel for an army of American rebels fighting to repel a royal siege. After nearly twenty years of neglect, the Horn Work was revitalized in the late 1770s to play an important role during the American Revolution. In a manner of speaking, it lived on to fight another day, and its story continues.

[1] South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Journal of the Commissioners of Fortifications, 1755–1770 (hereafter JCF), 22 December 1757. Gordon had already been working on the tabby wall at Dorchester without a formal contract, so his appointment to that job in late 1757 was retroactive (the Dorchester work was largely finished by 1758). He received payments “for attending the tappy work” and “setting the boxes” on the Horn Work on 6 April 1758, 14 September 1758, 12 October 1758, and 5 April 1759.

[2] JCF, 29 December 1757. On 16 March 1758, Holmes received £52 for two months work (£26 per month). On 18 May, however, the commissioners agreed to pay Holmes £40 per month retroactively, “in consideration of his having his son & another white lad to assist him, and his Negro carpenter often employed in his trade.” On 7 September, the commissioners agreed to pay them £52 per month “in consideration of John Holmes [his] extraordinary diligence and his son doing full duty as an overseer & giving constant attendance.” This arrangement continued through the end of October or early November, after which time the labor force diminished and Holmes’s salary returned to £40 per month (see 7 December 1758). On 4 January 1759, however, Holmes received £46 for the month of December, £6 of which was for his son’s work. John Holmes received a final payment of £40 on 5 April 1759, for wages due 3 April.

[3] See the expenses listed in JCF, 2 February and 2 March 1758, which suggest that more than 400 laborers (including soldiers) were divided between the Horn Work and the fortifications at White Point in February 1758. On 9 and 23 February 1758, the commissioners paid the firm of Ogilvie & Ward and William Banbury each for five hogsheads of rum “for the soldiers employed on the new Works” and “for the labourers on the North Line”; Fitzhugh McMaster, Soldiers and Uniforms: South Carolina Military Affairs, 1670–1775 (Columbia: South Carolina Tricentennial Commission, 1971), 59.

[4] Terry W. Lipscomb, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, October 6, 1757–January 24 1761 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1996), 137 (18 March 1758); JCF, 22 March 1758.

[5] JCF, 19 January 1758, 13 April 1758.

[6] JCF, 9 February 1758.

[7] JCF, 6 October 1757, 17 November 1757, 2 February 1758, 20 April 1758, 27 April 1758, 15 March 1759.

[8] The use of hired enslaved laborers for government construction projects in Charleston was very common before 1865, and the paper trail of the practice is voluminous; the standard rate of pay in the colonial period was £0.7.6 (currency) per day. See, for example, Episode No. 73. My labor estimates are based on data collected from the Journal of the Commissioners of Fortifications, a full discussion of which fills multiple pages. Until I have occasion to publish my conclusions and methodology in a fuller form, I remain confident that my estimates are reasonable and sound.

[9] See shell payments to Daniel Crawford, John Holmes, Colonel Robert River in the Journal of the Commissioners of the Fortifications, 13 July 1758, 3 August 1758, 17 August 1758; and payments for lime to Robert Rivers and then to Jonathan Scott “for the North Works” on 5 January 1758, 8 June 1758, and 20 July 1758.

[10] Journal of the Commissioners of Fortifications, 27 October 1757, 12 November 1757, 1 December 1757, 22 December 1757.

[11] John Ioor, for example, proposed to burn shells very near the Dorchester construction site to save money on cartage; see JCF, 23 June 1757, 19 September 1757, 13 April 1758.

[12] JCF, 15 June 1758, 22 June 1758, 1 September 1758.

[13] JCF, 2 March 1758, 24 July 1758, 1 September 1758.

[14] JCF, 21 July 1758.

[15] Governor Lyttelton appointed Roupell to serve as a commissioner for constructing Fort Lyttelton in September 1757 and appointed him to the board of Commissioners of Fortifications on 2 March 1758; he drew profiles of the platforms and embrasures of the Port Royal fort for the commissioners in September 1758; see JCF, 10 September 1757, 16 March 1758, 7 September 1758. For a discussion of Roupell’s famous illustration of “Mr. Peter Manigault and his Friends,” ca. 1760, see Anna Wells Rutledge, “After the Cloth Was Removed,” Winterthur Portfolio 4 (1968): 47–62.

[16] JCF, 5 April 1759.

[17] See grand jury presentments in South Carolina and American General Gazette, 20–27 April 1770; South Carolina Gazette, 24 May 1773; South Carolina Gazette, 3 June 1774. John Muller, A Treatise Containing the Practical Part of Fortification (London: Millar, 1755), 193–94, recommended a bread of ten feet for most gateways, while larger and more formal gates might be slightly wider.

[18] Muller, A Treatise, 193–94.

[19] William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, volume 1 (New York: David Longworth, 1802): 425; Bernhard A. Uhlendorf, ed. and trans., The Siege of Charleston. With an Account of the Province of South Carolina: Diaries and Letters of Hessian Officers from the von Jungkenn Papers in the William L. Clements Library (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1938), 291.

[20] JCF, 9 November 1758, 7 December 1758. Note that a third schooner and boat delivering materials to Fort Johnson continued in service until April 1759.

[21] JCF, 15 February 1759. This day also includes the “proceeds of the sales of two schooners & 3 horses sold at vendue.”

[22] JCF, 29 March 1759.

[23] It’s impossible to reconstruct the total cost of constructing the Horn Work in 1757–59, but the amount was certainly over ten thousand pounds South Carolina currency. On 13 April 1758, the Commissioners of the Fortifications noted that their funds were “reduced to about thirty thousand pounds currency,” and resolved to spend “ten thousand pounds of it in securing the Horn Work on the north of Charles Town and the other supply of twenty thousand pounds on the works at White Point.”

[24] Douglas R. Cubbison, The British Defeat of the French in Pennsylvania 1758: A Military History of the Forbes Campaign Against Fort Duquesne (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2010), 28; Sylvester K. Stevens and Donald H. Kent, eds., The Papers of Col. Henry Bouquet (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical Commission, 1941), Series 21643, page 177; series 21644, part 1, 49–50; 200–2; Michael Norman McConnell, Army and Empire: British Soldiers on the American Frontier, 1758–1775 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 73.

PREVIOUS: The Rise of Charleston’s Horn Work, Part 1

NEXT: Juneteenth, Febteenth, and Emancipation Day in Charleston

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments