Reviving Apparently Dead Bodies in 1790s Charleston

Processing Request

Processing Request

In the late summer of 1793, the City of Charleston ratified an ordinance requiring the proprietors of pubs and barrooms to assist physicians attempting to revive the bodies of “apparently dead” persons lingering in a state of “suspended animation.” This curious and long-forgotten law was prompted by advice from local doctors who followed trans-Atlantic reports of cutting-edge medical experiments of the day. Although the reanimation techniques of the 1790s involved procedures both ghoulish and comical, such efforts formed the groundwork of the modern science of resuscitation that we take for granted today.

Today’s topic might seem tailor-made for the Halloween season, complete with gothic scenes involving the use of spiritous liquors, tobacco smoke, and electricity to awaken the dead, but it’s based entirely on factual events and legitimate scientific reasoning. While this Charleston-centered story focuses on a poorly-remembered episode of local history, it’s important to recognize that it forms a small part of a much larger story that was unfolding on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean during the second half of the eighteenth century. The local paper trail of evidence related to this morbid topic is fragmentary and incomplete, so we have to look across the sea to Europe to understand why and how Charlestonians of the 1790s sought to restore the dead to life.

At the root of this ghoulish subject is an ancient and universal fear succinctly expressed in the modern term “taphophobia”—the fear of being buried alive. As I mentioned in an earlier episode about taphophobia (see Episode No. 88), this fear is itself rooted in another ancient mystery that persists to this day. The distinction between life and death is not always as clear and definite as we might think. Over the past many centuries, a number of witnesses have reported that people who appeared to be dead were suddenly restored to life without human interference. Such cases were deemed miraculous in millennia past, while observers during the Enlightenment began to explore the phenomenon using more analytical methods.

At the root of this ghoulish subject is an ancient and universal fear succinctly expressed in the modern term “taphophobia”—the fear of being buried alive. As I mentioned in an earlier episode about taphophobia (see Episode No. 88), this fear is itself rooted in another ancient mystery that persists to this day. The distinction between life and death is not always as clear and definite as we might think. Over the past many centuries, a number of witnesses have reported that people who appeared to be dead were suddenly restored to life without human interference. Such cases were deemed miraculous in millennia past, while observers during the Enlightenment began to explore the phenomenon using more analytical methods.

Through observation and experimentation, scientists noted that the movement or “animation” of human organs and limbs demonstrated the existence of some mysterious “vital force” that was synonymous with life. Bodies lacking animation and vitality were generally considered to be dead, but some people who appeared to have died were later restored to life. Scientists realized that the physical appearance of death, or “want of vitality,” was not sufficient proof of the fact. Putrefaction, or decomposition of the flesh, was the only incontrovertible sign of death. A brief remark on this subject, published in Boston in the spring of 1786 and reprinted in Charleston, provides a useful synopsis of contemporary thought:

“From a variety of faithful experiments, and incontestable facts, it is now considered as an established truth, that the total suspension of the vital functions in the animal body is by no means incompatible with life; and consequently, the marks of apparent death may subsist without any necessary implication of an absolute extinction of the animating principal. The boundary line between life and death, or the distinguishing signs of the latter, are objects to which the utmost efforts of the human capacity have never yet attained.”[1]

Following the line of logical thought that characterized the Age of Reason, many scientists posed the following question: If the appearance of death was, in some cases, only a suspension of the animating spirit, is it possible to restore the vital spark to lifeless bodies? Experimentation on victims of drowning, suffocation, hanging, and other accidents proved that the restoration of life was possible in some but not all cases. To improve their rate of success, physicians continued to experiment and refine the methods of what became known as the science of resuscitation.

The leading force in this international scientific campaign was a Dutch organization formed in Amsterdam in 1767. The Maatschappij tot Redding van Drenkelingen (the Society for Rescuing Drowning Persons) caught the public’s attention by offering rewards to anyone attempting to re-animate persons apparently dead, and by publishing summaries of successful and unsuccessful cases. Within a few years after the publications of the Dutch society’s first reports, similar organizations appeared in Milan, Venice, Hamburg, Paris, and London. In the British capital, the Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned, founded in 1774, soon became the Royal Humane Society and sparked the creation of similar organizations across the British Isles. In the aftermath of the American Revolution in the 1780s, Humane Societies were formed in Philadelphia, New York, Boston, Baltimore, and a number of other cities and towns across North America.[2]

The physicians of Charleston did not organize a Humane Society during the 1780s, but they would have been familiar with the movement. The Charleston Library Society was in the habit of importing scientific publications directly from London, and the local newspapers of that era printed numerous descriptions of the activities of life-restoring societies across the United States and abroad. In short, the people of late-eighteenth-century Charleston, especially the learned community of physicians, were aware of the contemporary methods and strategies used to restore life to persons who appeared to be dead.[3]

The physicians of Charleston did not organize a Humane Society during the 1780s, but they would have been familiar with the movement. The Charleston Library Society was in the habit of importing scientific publications directly from London, and the local newspapers of that era printed numerous descriptions of the activities of life-restoring societies across the United States and abroad. In short, the people of late-eighteenth-century Charleston, especially the learned community of physicians, were aware of the contemporary methods and strategies used to restore life to persons who appeared to be dead.[3]

One could fill a dissertation with details of the reanimation methods advocated during the 1780s. At the risk of oversimplifying this complex topic, I’ll reduce the field to four principal strategies. The first involved the application of heat to cold bodies by wrapping them in blankets, placing them in warm beds with naked companions, or surrounding them with warm bricks and bladders of hot water. Second, rescuers were encouraged to rub vigorously the skin of apparently-dead bodies, especially around the heart, to excite the flesh and organs. For reasons not entirely clear, the leading practitioners of this science advocated the use of flannel cloths and spiritous liquors to enhance the excitation of the victim’s skin.

Third, it was thought necessary to inflate the internal organs. Bellows inserted into a nostril could be used to pump air into lifeless lungs—a task that could also be done with one’s mouth over the victim’s mouth if bellows were not available. To inflate and excite the bowels, most of the leading scientists of the late eighteenth century advocated the use of an older technique used to treat a wide variety of ailments. In the parlance of that era, physicians were directed to deploy tobacco smoke “in the enemetic form”; or, in another choice phrase, “to throw tobacco smoke gently into the fundament.” That’s right, were talking about the once-popular tobacco smoke enema. Using a tube connected to a pipe, glyster, bellows, or other apparatus, rescuers believed that the pungent herbal smoke would stimulate the bowels into performing their natural functions.[4]

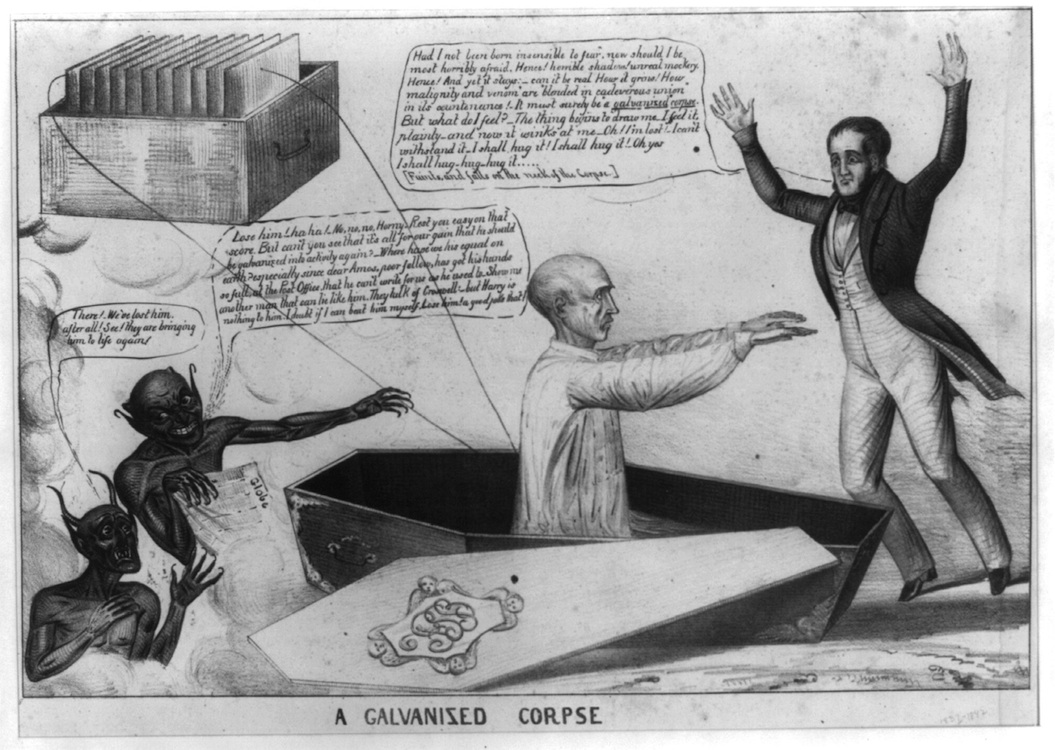

The fourth strategy for human reanimation that appeared in the 1780s was based on the ground-breaking research of the husband-and-wife team of Luigi and Lucia Galvani. Their experiments with new-fangled electrical capacitors and the legs of deceased frogs shed new light on the nature of the “vital spark” that sustained life. The Galvanis coined the term “animal electricity” to describe what they believed was an “electrical fluid” flowing through the muscles and nerves of all living beings. Advocates of human reanimation quickly adapted the Galvanis’ ideas to human subjects, using primitive battery cells attached to wires and electrodes to communicate mild electrostatic shocks to apparently-dead bodies. This application became widespread in the 1790s and provided inspiration for the reanimated monster in Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.[5]

The earliest evidence that the physicians of Charleston were paying attention to these life-restoring techniques appeared in January 1790, two weeks after the formal creation of the Medical Society of South Carolina. At that time, each of the society’s founding members subscribed a sum of money in order to inaugurate a dispensary providing free health care to the community’s poorest citizens. In a published announcement of its goals, the society articulated a desire to augment their charitable work by forming “a Humane Society for the recovery of drowned or suffocated persons.”[6]

The earliest evidence that the physicians of Charleston were paying attention to these life-restoring techniques appeared in January 1790, two weeks after the formal creation of the Medical Society of South Carolina. At that time, each of the society’s founding members subscribed a sum of money in order to inaugurate a dispensary providing free health care to the community’s poorest citizens. In a published announcement of its goals, the society articulated a desire to augment their charitable work by forming “a Humane Society for the recovery of drowned or suffocated persons.”[6]

The plan announced by the Medical Society of South Carolina was contemporary with a new development in life-restoring technology in England. A physician working in the port town of Lancaster developed an “apparatus,” which had been exhibited to and endorsed by the Royal Humane Society of London. In the summer of 1790, the popular Gentleman’s Magazine of London printed an illustration and description of this “very ingenious and useful apparatus for the communication of heat to bodies apparently dead.” The “machine” in question was a hollow box, probably made of sheets of tin, measuring five and a half feet long and bearing a strong resemblance to a coffin. Instead of placing a body inside its walls, however, the apparently-dead body was placed on top of the device between molded rests for the head and feet. A pair of funnels above the head allowed users to fill the apparatus with hot water, while a spigot below the feet allowed them to drain the water after use.[7]

Beyond its endorsement of the warming apparatus, also known as a “couchette,” the Royal Humane Society of London also encouraged first-responders to create “animation boxes” containing various supplies to be used in resuscitation efforts. Such pre-assembled kits included items like drag nets and hooks to recover bodies from the water, blankets, flannels, spiritous liquors, bellows, tobacco, and electrical batteries.[8] Among the physicians who embraced this life-restoring technology was a Charlestonian, Elisha Poinsett (ca. 1738–1803), who spent much of the 1780s working in England. Shortly after his return to South Carolina, Dr. Poinsett initiated a conversation that animated his colleagues to dabble in the field of resuscitation.

Our knowledge of this curious episode in Charleston history is greatly enhanced by the survival of the early manuscript journals of the Medical Society of South Carolina, now held at the Waring Historical Library at the Medical University of South Carolina. At a meeting of that society on April 27th, 1793, Dr. Elisha Poinsett informed his colleagues that he had imported an “apparatus (as used by the Humane Society of London) for the recovery of persons apparently dead from drowning, or other causes.” Dr. Poinsett offered to sell the apparatus to the Medical Society “at cost and charges,” and the society accepted his offer. To make the best use of this equipment, the society ordered its secretary “to give public intimation of this in the [local news] papers,” and directed that the apparatus should “be deposited with Dr. Poinsett, that it may be had recourse to when wanted.”[9]

Two weeks later, two of Charleston’s daily newspapers printed the following public notice that appeared in multiple issues in late May 1793: “The Medical Society of South Carolina, give notice, that they have procured an apparatus (as used by the Humane Society of London) for the recovery of persons apparently dead from drowning, or other causes, and that the same is deposited with Dr. Poinsett, at No. — Broad-street, where it may be had on application. A member of the society, will likewise attend, if required, in order to give the necessary medical assistance.”[10]

The members of the Medical Society presumably knew how to use the apparatus and had learned, through their professional communications, the steps to be employed in reviving apparently-dead bodies. But the society sought to disseminate this information to a broader audience that included people without medical training. To strengthen the impact of their efforts, some members of the Medical Society suggested the idea of partnering with the municipal government. At a meeting of the Medical Society in late June, the members appointed a committee “to prepare & present a petition to the City Council for the purpose of inducing their co-operation in promoting the resuscitation of persons apparently dead.” Furthermore, the society ordered this committee of physicians “to draw up directions for accomplishing the same.”[11]

Sometime during the month of July 1793, members of the Medical Society’s committee attended a meeting of Charleston’s City Council, then held in the upper floor of the Exchange Building. Although no records of the municipal government survive from this era, it seems that the physicians representing the Medical Society petitioned for the city’s assistance in their plan to revive apparently-dead bodies. They described to Council their plan to make their resuscitation apparatus available to the public and their intention to draft a set of directions for it use. The society did not necessarily ask the city to contribute financially to this effort; instead, they asked the local government to endorse and promote the work planned by the Medical Society. As a result of this conversation, City Council apparently agreed to draft a bill to oblige certain citizens and encourage the community in general to assist the society’s reanimation campaign. Council might also have agreed to cover the costs associated with printing and distributing copies of the proposed directions for restoring to life bodies that appeared to be dead.

At a meeting held on July 27th, the committee of physicians who had addressed City Council reported to the Medical Society that they had enjoyed a productive meeting with the municipal leaders, and “that their intentions were in a fair way of being carried into the desired effect.” Next, “Dr. David Ramsay read to the society the directions drawn up by the committee for the purpose of recovering persons apparently dead from drowning &c.” Modern audiences will be disappointed to learn that the society’s secretary did not copy the proposed directions into the minutes of the meeting in question. Instead, he simply noted that the learned group of physicians listened to Dr. Ramsay read the proposed directions aloud. Some discussion of revisions might have occurred that evening, but the society’s president laid the directions aside temporarily and “ordered that they do circulate with the [other medical] papers for the consideration of the society.”[12]

At a meeting held on July 27th, the committee of physicians who had addressed City Council reported to the Medical Society that they had enjoyed a productive meeting with the municipal leaders, and “that their intentions were in a fair way of being carried into the desired effect.” Next, “Dr. David Ramsay read to the society the directions drawn up by the committee for the purpose of recovering persons apparently dead from drowning &c.” Modern audiences will be disappointed to learn that the society’s secretary did not copy the proposed directions into the minutes of the meeting in question. Instead, he simply noted that the learned group of physicians listened to Dr. Ramsay read the proposed directions aloud. Some discussion of revisions might have occurred that evening, but the society’s president laid the directions aside temporarily and “ordered that they do circulate with the [other medical] papers for the consideration of the society.”[12]

The directions proposed by the Medical Society might have been completed by August 14th, when its committee members attended another meeting of City Council. At that time, the city wardens probably read aloud the text of a bill to assist the Medical Society’s efforts to revive apparently-dead bodies and moved that project along the path to ratification. Physicians representing the society then asked the city to contribute public funds to the purchase of various supplies to facilitate the creation of what was likely an “animation box,” and to cover the cost of printing the necessary directions. In response, the City Council mooted and adopted two curious resolutions:

“Resolved that the Medical Society of South Carolina agreeably to their requisition be authorised to purchase one or two saines [seines], drag hooks, & drag nets, four blankets, one or two pair of bellows, eighteen yards of flannel, and two dozen of empty gin jugs for the purpose of assisting the Medical Society of South Carolina in their humane intentions to restore to life persons under suspended animation, and that the city council will reimburse the expenses of the same.

Resolved that the city council will pay for six hundred copies of the directions for restoring ‘persons apparently dead to life’ drawn up by the Medical Society of South Carolina, who are hereby authorized to have the same printed.”[13]

Five days later, on Monday, the 19th of August, 1793, the members of Charleston’s City Council ratified “An Ordinance for assisting the Medical Society of South Carolina, in their humane intentions, to restore to life persons under suspended animation.” Citizens became aware of the new law the following morning, when Charleston’s principal newspaper of that era, the City Gazette, printed the full text without any sort of commentary or reaction. After appearing in multiple editions of local papers printed during the autumn of 1793, the ordinance later appeared in several compilations of city laws printed in the late 1790s and early 1800s. These documents provide modern readers with the outline of an intriguing story, but leave many questions unanswered.

The preamble of the 1793 law stated that “the Medical Society of South Carolina has brought forward a memorial to the city council of Charleston, praying them to aid and assist them in their humane intentions of attempting to restore persons apparently dead to life.” Without explaining the scientific theories behind this effort, and without explaining the proposed methodology for its implementation, the ordinance provided a set of mysterious orders directed at the proprietors of drinking establishments and restaurants rather than members of the medical profession: "All licenced retailers of spirituous liquors”—that is, every pub and barroom in the city limits—“are hereby compelled to receive into their house, by night as well as by day, the bodies of persons apparently dead, from drowning or other causes, which shall be brought to their houses within three hours from the time of the accident, and shall also furnish with all speed, all such articles as may be necessary to assist in restoring to life all such bodies which may be brought as aforesaid to their houses.”

To encourage the proprietors of drinking establishments to assist with such reanimation efforts, the city pledged to compensate them for all supplies that might be consumed during the experience, and a further reward of twenty shillings. Private citizens, not the proprietors of drinking establishments, who opened their homes or businesses to assist in the reanimation of apparently-dead bodies would receive the same compensation and reward as the aforementioned licensed retailers. If any retailer of spirituous liquors refused to admit apparently-dead persons into their establishments, at any time during the day or night, they would immediately forfeit their business license.

The text of the city ordinance of 1793 did not prescribe any methods or techniques for reanimating apparently-dead bodies. Rather, it directed citizens to a set of instructions composed and endorsed by the Medical Society of South Carolina. The ordinance required every licensed retailer of spirituous liquors to “constantly keep in public view, printed directions for restoring persons apparently dead to life, which directions, drawn up by the Medical Society of South Carolina, shall be given them gratis.” Drinking establishments failing to post the printed directions would be subject to a fine imposed by City Council (not exceeding the cost of their license).

The text of the city ordinance of 1793 did not prescribe any methods or techniques for reanimating apparently-dead bodies. Rather, it directed citizens to a set of instructions composed and endorsed by the Medical Society of South Carolina. The ordinance required every licensed retailer of spirituous liquors to “constantly keep in public view, printed directions for restoring persons apparently dead to life, which directions, drawn up by the Medical Society of South Carolina, shall be given them gratis.” Drinking establishments failing to post the printed directions would be subject to a fine imposed by City Council (not exceeding the cost of their license).

For every successful reanimation effort, the City of Charleston offered to pay a reward of £4 sterling, to be “distributed among the first four persons who shall attempt the recovery of any person or persons apparently dead, from drowning or other accidents.” Similarly, the city offered to pay £2 for unsuccessful attempts, distributed in the same manner, provided that the parties could certify three conditions: that they utilized “the means to be recommended by the Medical Society, or by any skillful physician or surgeon,” that they commenced the reanimation efforts “within the first three hours from the accident happening,” and that they persisted in the effort for at least three hours.[14]

At the end of August 1793, the members of the Medical Society of South Carolina heard a brief report from their colleagues who had recently conferred with City Council. The physicians reported that the city government had ratified and published an ordinance relative to “the necessary measures for recovering persons apparently dead from drowning &c.” The committee also reported that Council had agreed to reimburse the society for the purchase of various materials related to their life-saving efforts. Dr. David Ramsay was then instructed to draw funds from the city to cover the cost of the nets, drag hooks, bellows, blankets, flannel, and gin jugs approved on August 14th. Furthermore, the society resolved to publish copies of “the directions for the recovery of ‘persons apparently dead to life.’”[15]

But the Medical Society did not immediately distribute printed copies of its instructions. Nearly seven months later, in late April 1794, the president of the Medical Society, Dr. Alexander Baron, reported to his colleagues that he had in his possession 600 copies of the “directions for the recovery of persons under suspended animation from drowning and other causes” that had been drafted and approved during the previous summer. The society then resolved to send 500 copies of the printed directions to City Council “for distribution,” while reserving 100 copies “for the use of the Society.”[16]

At this point, the paper trail of this curious story turns as cold as a mummy’s tomb. Of the six hundred copies of the printed directions mentioned in April 1794, not a single copy can now be found. Furthermore, none of the several newspapers active in Charleston during that era mentioned or quoted from the directions drafted by the Medical Society of South Carolina. On several occasions during the late 1790s and early 1800s, however, various Charleston newspapers printed excerpts from similar directions endorsed by medical organizations in other communities in North America and in Europe. This journalistic phenomenon might have stemmed from the ubiquity of the Medical Society’s directions within the Palmetto City. If copies of the 1794 text really were displayed in every drinking establishment and restaurant in Charleston, there would have little need for the local press to reproduce that information in their valuable columns. Local readers, on the other hand, might have been interested in comparing Charleston practices to the protocols used in distant communities to reanimate apparently-dead bodies.[17]

Without any surviving copies of the directions distributed by the Medical Society in 1794, it is now impossible to describe definitively the reanimation methods intended to be used in Charleston. By noting a few clues within the aforementioned texts of 1793 and comparing them with the directions endorsed by contemporary medical organizations in other cities, however, we can reconstruct a plausible outline of the life-restoring methodology used in Charleston during the 1790s.

Without any surviving copies of the directions distributed by the Medical Society in 1794, it is now impossible to describe definitively the reanimation methods intended to be used in Charleston. By noting a few clues within the aforementioned texts of 1793 and comparing them with the directions endorsed by contemporary medical organizations in other cities, however, we can reconstruct a plausible outline of the life-restoring methodology used in Charleston during the 1790s.

We can surmise, for example, that the Medical Society intended to wrap apparently-dead bodies in blankets and place them atop the water-filled apparatus or couchette imported from London. The physicians requested bellows to inflate the lungs and perhaps the bowels of their subjects. The city ordinance of 1793 required the proprietors of pubs, barrooms, and taverns to provide “all such articles as may be necessary to assist in restoring life to all such bodies which may be brought . . . to their houses.” Such materials probably included fire to heat the water within the apparatus, spiritous liquors to dampen the flannel cloths used to rub the victim’s body, and tobacco to fumigate their fundament. A small volume of alcohol might have been required to fill a Leyden jar if a member of the medical community brought a portable electrostatic generator to the scene. Because the city’s reanimation ordinance required such efforts to continue for at least three hours, the proprietors of taverns were probably also expected to provide a bit of food and drink to the first-responders.[18]

Armed with a vague notion of how the Medical Society of South Carolina and the City of Charleston proposed to reanimate apparently-dead bodies, we can now turn our attention to several important questions of application: Were the directions printed by the Medical Society actually posted in various drinking establishments in Charleston? How many lifeless corpses were successfully revived? Which drinking establishments hosted such dramatic scenes of emergency medicine? How many people received compensation from the city government for attempting to restore the dead to life?

The answers to these questions were once recorded within the manuscript journals of Charleston’s City Council meetings and in the ledgers kept by the city’s treasurers. Those materials, along with most of the city early records, vanished during the local chaos that accompanied the final months of the American Civil War (an event I described in Episode No. 79 as “The Great Memory Loss of 1865”). The loss of those records, I regret to say, now renders it impossible to provide a satisfying conclusion to the intriguing story of reanimating apparently-dead bodies in late eighteenth-century Charleston.

The text of Charleston’s reanimation ordinance of 1793 appears in compilations of city ordinances published in 1796, 1802, and 1818, after which time it disappeared from the city’s published records. If City Council repealed the ordinance at some point after 1818, no record of that action can now be found.[19] The Medical Society of South Carolina had lobbied the city government to pass the 1793 ordinance, but that body of physicians, unlike many contemporary organizations, did not publish any subsequent reports of its successes and failures in this field. In short, this curious chapter in Charleston’s long history remains unfinished, condemned to linger in state of suspended animation.

The medical language and methods described in today’s program might sound bizarre or even comical to some audiences, but they continue to form a part of our present culture. The ground-breaking experiments to reanimate lifeless bodies in the late eighteenth century laid the foundation for the now-well-established science of resuscitation. Rather than using bellows to inflate the lungs, we teach the practice of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Rather than rubbing patients vigorously with gin-soaked flannel, we advocate the chest-pumping technique of CPR. Rather than zapping hearts and heads with primitive electrostatic charges, we use a more refined electric defibrillator to achieve essentially the same restorative effect.

Charleston’s forgotten campaign to reanimate apparently-dead bodies in 1790s has all the ingredients for a good Halloween story, so I hope you enjoy sharing it with your friends and family. If anyone doubts its truth, be sure to tell them that you’re not just blowing smoke up their fundament!

[1] [Charleston, S.C.] Columbian Herald, 18 May 1786, page 2, “Boston, March, 1786.”

[2] For more information on the spread of such organizations, see Amanda Bowie Moniz, From Empire to Humanity: The American Revolution and the Origins of Humanitarianism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016); Ciarán McCabe, “The Humane Society Movement and the Transnational Exchange of Medical Knowledge in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries,” Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh 49 (June 2019): 158–64.

[3] See, for example, the instructions published in 1773 by Dr. Alexander Johnson were published serially in three newspapers in Charleston: Columbian Herald, 29 May, 1 June, and 5 June 1786; State Gazette of South Carolina, 1, 3, 8, 12 June 1786; Charleston Morning Post, 27 May, 1 June 1786; see also Columbian Herald, 9 August 1796, page 2.

[4] Use of medicinal tobacco was becoming controversial in the early 1790s; see William Hawes, ed., Transactions of the Royal Humane Society from 1774 to 1784: With An Appendix of Miscellaneous Observations on Suspended Animation, to the Year 1794 (London, 1795), 503–40. The quoted phrase appears in Columbian Herald, 9 August 1796, page 2, “Royal Humane Society.”

[5] For an overview of the early use of medical electricity, see Paola Bertucci and Guiliano Pancaldi, eds., Electric Bodies: Episodes in the History of Medical Electricity (Bolongna: CIS, 2001).

[6] [Charleston, S.C.] City Gazette, 11 January 1790, page 2.

[8] McCabe, “The Humane Society Movement,” 160; for a good summary of the techniques and equipment, see Hawes, Transactions of the Royal Humane Society, 489–94.

[9] Minutes of the Medical Society of S.C., volume 1789–1810, page 68 (27 April 1793), Medical University of South Carolina, Waring Historical Library.

[10] State Gazette of South Carolina, 15 May 1793, page 3, “To the Public.”

[11] Minutes of the Medical Society of S.C., volume 1789–1810, page 70 (29 June 1793). The committee included Thomas H. McCalla, David Ramsay, Elisha Poinsett, and William Lehre.

[12] Minutes of the Medical Society of S.C., volume 1789–1810, page 73 (27 July 1793).

[13] The text of these City Council resolutions appears in the Minutes of the Medical Society of S.C., volume 1789–1810, page 77 (31 August 1793).

[14] City Gazette, 20 August 1793, page 3.

[15] Minutes of the Medical Society of S.C., volume 1789–1810, pages 74–78 (31 August 1793). The minutes of this meeting include the complete text of the city ordinance of 19 August.

[16] Minutes of the Medical Society of S.C., volume 1789–1810, page 100 (26 April 1794).

[17] See, for example, Columbian Herald, 22 August 1794, page 4; Columbian Herald, 19 September 1794, page 2; City Gazette, 20 September 1800, page 2; City Gazette, 2 April 1801, page 2; Carolina Gazette, 2 August 1805, page 4.

[18] For a brief description and illustration of a portable electrostatic device endorsed by the Royal Humane Society, see The Gentleman’s Magazine, April 1792, pages 299–300.

[19] Dominick Augustin Hall, comp., Ordinances of the City Council of Charleston, In the State of South Carolina, Passed Since the Incorporation of the City (Charleston, S.C.: John MacIver, 1796), 97; Alexander, comp., Ordinances of the City Council of Charleston, In the State of South Carolina, Passed since the Incorporation of the City (Charleston, S.C.: W. P. Young, 1802), 107; City Council of Charleston, Digest of the Ordinances of the City Council of Charleston, from the Year 1783 to July 1818 (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1818), 220.

NEXT: Wielding the Sword of State in Early South Carolina

PREVIOUSLY: Educating Antebellum Tradesmen: The Charleston Apprentices’ Library Society

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments