Representing Charleston at the 1926 National “Charleston” Contest

Processing Request

Processing Request

On a pair of snowy evenings in Chicago in February 1926, two young dancers from Charleston competed with other couples to determine the most proficient “Charlestoners” in the United States. Spectators judged their steps to be the most graceful and refined, especially in contrast to the contestants who flailed through the dance with bewildering speed. In the end, the Lowcountry couple failed to win honors for their subdued interpretation of the popular dance, but the mayor and the local business community deemed the entire Jazz-Age adventure to be a marketing triumph.

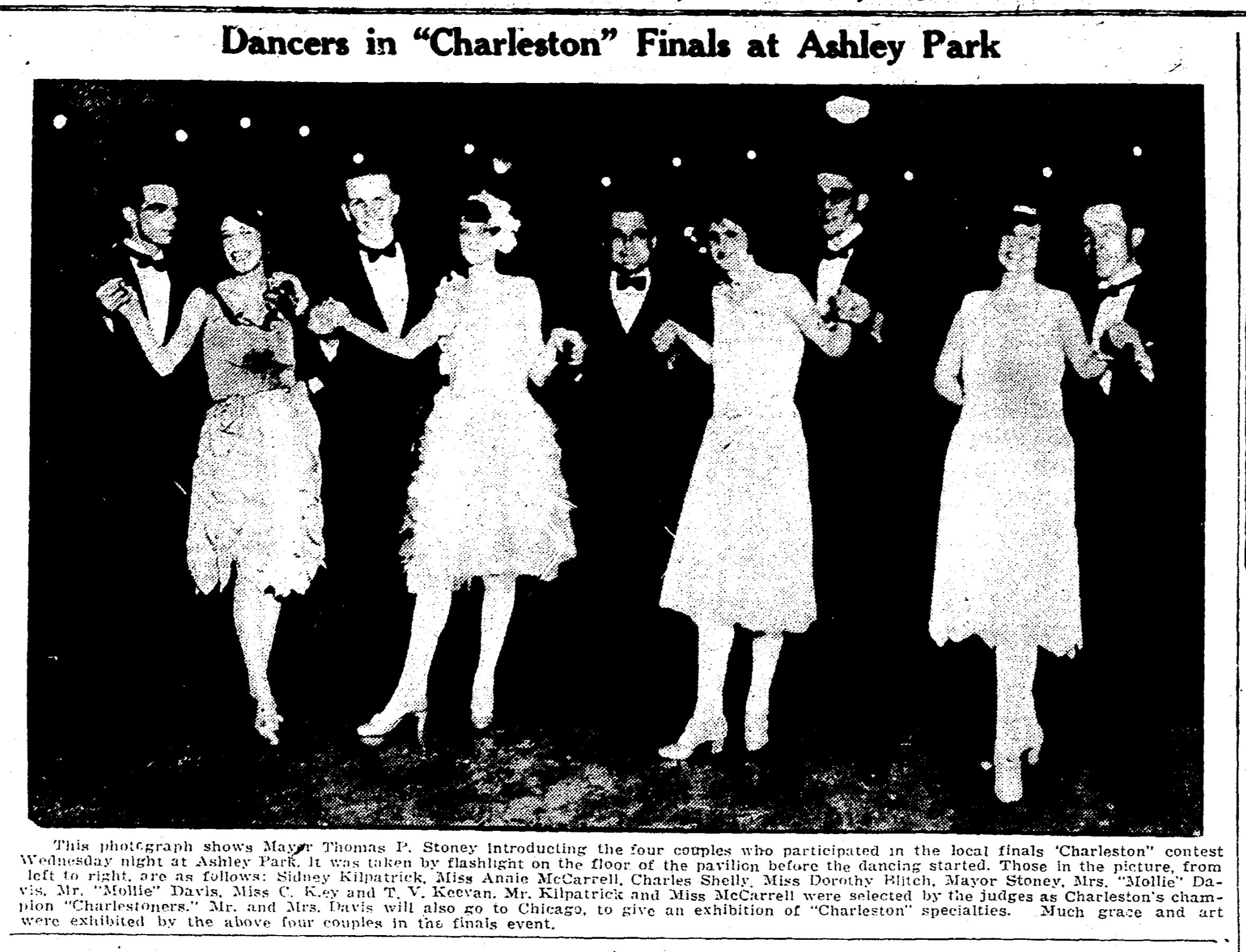

In the summer of 1925, most Charlestonians were ambivalent about the name-sake dance then popular across the country. When Grace Jackson of Brooklyn, mother of the young professional dancer, Bee Jackson, asked the Mayor of Charleston to hand her daughter the keys to the city for all the work she was doing to promote it, local leaders scratched their heads. Mrs. Jackson’s request started a conversation, however, that provoked city officials and local business leaders to consider embracing the marketing potential of the popular dance sensation. The invitation to send a Charleston delegation to a national dance competition in Chicago hooked the city’s interest, and a series of local elimination dances in January 1926 identified best (white) amateur Charleston-dancing couple in the area.

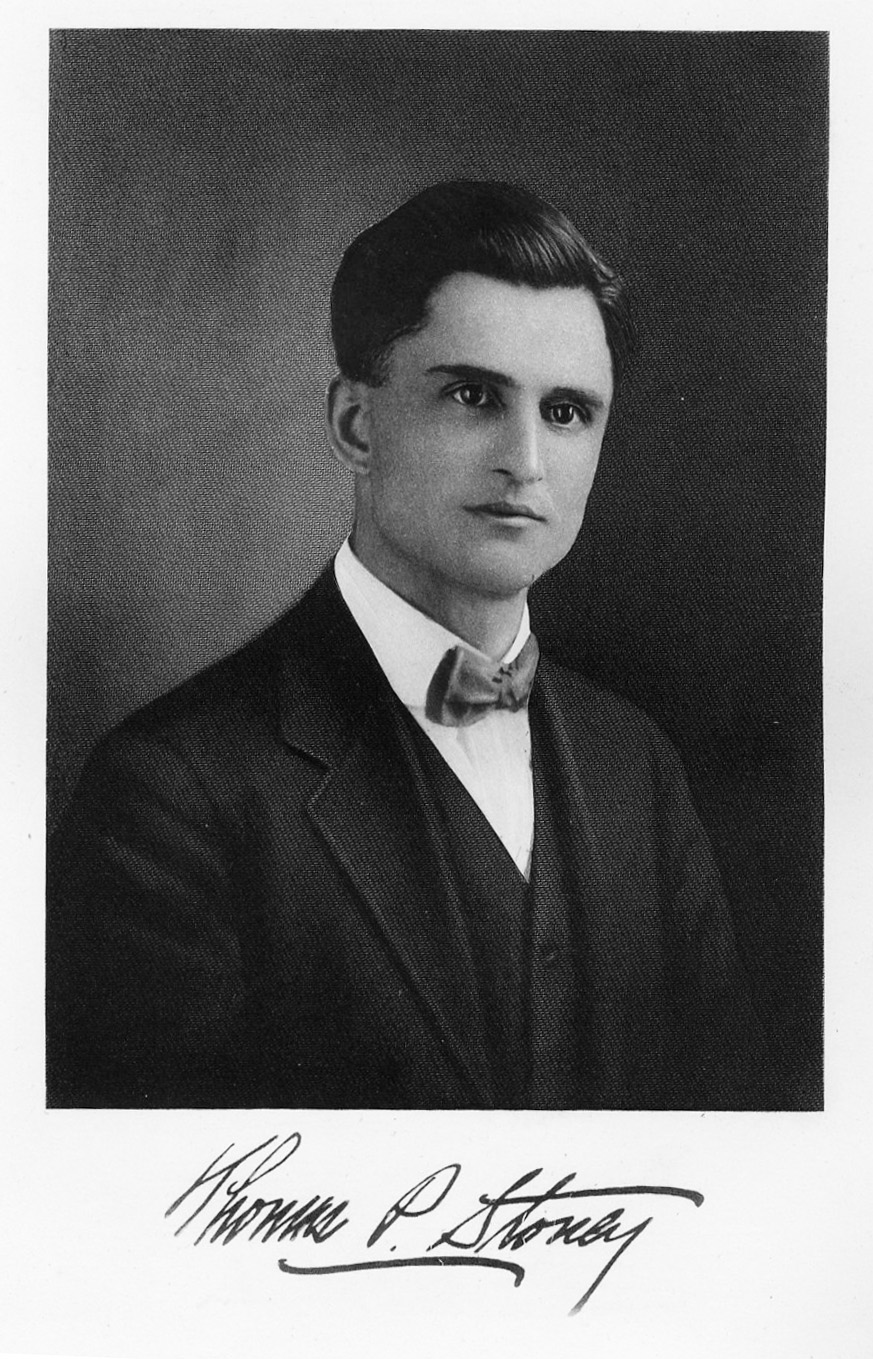

From the municipal perspective, the purpose of sending a local delegation to the national competition was two-fold: to capitalize on free advertising for the City and Port of Charleston, and to prove to critics near and far that the “Charleston” dance could be performed in a respectable and even elegant manner. On Saturday, February 6th, the Charleston delegation boarded a train for Chicago. The party included Mayor Thomas P. Stoney and his wife, Chamber of Commerce representative Sam Berlin and his wife, competitors Sidney Kilpatrick and Annie McCarrel, with Annie’s mother as chaperone, exhibition dancers G. E. Rhett Davis, better known as “Mollie,” and his wife, Edith, dance coach Jack Simmons, and two local reporters. After a royal welcome in Chicago on Monday, February 8th, the Charleston delegation motored to the Chicago Beach Hotel for a bit of rest before the competition began.

The 1926 “Charleston” championship in Chicago actually included two separate contests held on successive evenings. On Monday, February 8th, dancers from twenty-eight cities divided into four geographic groups to determine the best “Charlestoners” from the Northern, Southern, Eastern, and Western regions of the United States. On the evening of Tuesday, February 9th, all the competitors returned, regardless of their showing in the regional contest, to compete for the title of best overall Charleston-dancing couple in the nation.

The 1926 “Charleston” championship in Chicago actually included two separate contests held on successive evenings. On Monday, February 8th, dancers from twenty-eight cities divided into four geographic groups to determine the best “Charlestoners” from the Northern, Southern, Eastern, and Western regions of the United States. On the evening of Tuesday, February 9th, all the competitors returned, regardless of their showing in the regional contest, to compete for the title of best overall Charleston-dancing couple in the nation.

Despite its claims of being a national competition, embracing entries from California to Maine and from Texas to Michigan, the geographic representation was definitely limited. The contest organizers never published an official list of participants, and the total number of entries seems to have changed right up the last minute. Several contemporary newspapers printed imperfect lists identifying between twenty-five to thirty-two cities, but only twenty-eight cities appeared in Chicago to compete. In general, the 1926 national “Charleston” contest was very much a Midwestern affair, dominated by Ohioans and peppered with a handful of entries from Southern cities.[1]

Monday, February 8th: The Regional Championship

In the early evening, the contestants resting at the Chicago Beach Hotel packed up their dancing costumes and motored over to the Trianon ballroom, a massive rectangular brick edifice standing at the corner of Cottage Grove Avenue and Sixty-Second Street. Entering the lobby, guests saw an attractive display of promotional materials featuring Charleston, South Carolina, including photographs, maps, postcards for Magnolia Gardens, and information about various aspects of the city and port in general. Sam Berlin and his associates had assembled a wealth of information and were on hand to answer questions about the Palmetto city and state.

Moving through the opulent lobby and into the main hall, most of the small-town guests were awed by the magnitude of the venue. The vast, oval-shaped Trianon ballroom was reputed to be large enough to accommodate 3,000 couples dancing at the same time, while additional guests in the surrounding mezzanine observed from a number of luxury boxes. The Trianon even had its own radio station, broadcasting as WMBB, an acronym for “world’s most beautiful ballroom.” Music for the two-day dance competition in February 1926 was provided by the Trianon’s house band, the twelve-piece Dell Lampe Orchestra, which performed on a stage recessed into the periphery of the dance floor. Mayor Stoney and Sam Berlin, accompanied by their respective wives, occupied a luxurious box of honor in the mezzanine. While they overlooked the audience and dancers competing below, the Charleston dignitaries received complementary visits from a number of parties throughout the evening.

The much-anticipated revelries commenced after 10 p.m. with greetings and introductions by Harold Murphy, master of ceremonies for the two-day dance tournament. With a signal from Mr. Murphy, the brassy jazz orchestra stuck up a grand march for the entrance of the contestants. Annie McCarrel and Sidney Kilpatrick, Charleston’s winning dancers, then led a stately procession of twenty-eight couples into the cavernous room, where more than 3,000 spectators greeted them with a shower of thunderous applause. As the audience crowded around the contestants on the giant dance floor, the fifty-six young men and women danced freely for several minutes in the center of the room to shake off their nerves and loosen their limbs.

The Midwestern audience was eager to see a display of various styles of “Charleston,” as well as the moves of the Palmetto dancers in particular. Before the competition commenced, a reporter from the Associated Press informed the nation that “the couple from the City by the Sea will be the cynosure of all eyes at the magnificent Trianon tonight, for the other dancers in the competition will be eager to see just how the new terpsichorean art is performed in the city where it originated and after which it is named.” Similarly, the Charleston reporters on site also relayed descriptions back to the home-town readers. “In general the affair was a splendid one,” said Manning J. Rubin of the Charleston Evening Post, “and demonstrated that there are as many ways of dancing the ‘Charleston’ as there are of cooking rice in the city where the dance started.”

The Midwestern audience was eager to see a display of various styles of “Charleston,” as well as the moves of the Palmetto dancers in particular. Before the competition commenced, a reporter from the Associated Press informed the nation that “the couple from the City by the Sea will be the cynosure of all eyes at the magnificent Trianon tonight, for the other dancers in the competition will be eager to see just how the new terpsichorean art is performed in the city where it originated and after which it is named.” Similarly, the Charleston reporters on site also relayed descriptions back to the home-town readers. “In general the affair was a splendid one,” said Manning J. Rubin of the Charleston Evening Post, “and demonstrated that there are as many ways of dancing the ‘Charleston’ as there are of cooking rice in the city where the dance started.”

As in the local elimination rounds held in January, the contestants in this national event were required to demonstrate two contrasting styles of dance, the ballroom “Charleston” and the “stage or eccentric” “Charleston.” The competitors began the evening’s procession and ballroom displays attired in traditional black tuxedos and tasteful knee-length frocks. Charleston’s own Annie McCarrel wowed the audience with a modish Parisian-made dress of white chiffon taffeta silk, featuring “a tight bodice and very full skirt” with crystal appliqué accents, silver slippers with crystal buckles, and nude stockings, all of which had been donated by various Charleston shops in exchange for having their names mentioned in the newspaper.

Annie might have looked like the picture of feminine elegance, but she later admitted that she had been terrified and distressed. Shortly before the competition began on Monday evening, she and her partner, Sidney Kilpatrick, learned that each couple would have just two minutes to display their signature choreography for the judges. Back in Charleston, the couple had choreographed two contrasting five-minute routines when they competed in the local elimination rounds. Now there was no time to panic or complain as the orchestra trumpeted the opening march, and certainly no time to reconfigure their choreography. Rather than attempt to edit steps on the fly, Annie and Sidney decided to simply trim their familiar routine by more than half. As a result of this last-minute sacrifice, the crowd attending the Trianon ballroom that Monday evening never saw the couple’s fanciest steps, which were reserved for the climax of their prepared routine.

The local press coverage of this event provided no explanation of which cities were grouped into the four regional divisions, but it appears Charleston’s best amateur couple competed against dancers from Memphis, Tulsa, and Little Rock in the Southern division. Details of how the competition proceeded in general are also lacking from news reports, but one important feature of the evening received copious attention. After the ballroom portion of the competition, the fifty-six contestants changed into “collegiate or fancy costume” for the more energetic “eccentric” portion of the show. This style allowed more freedom of expression, of course, and therefore required less-restrictive clothing. In an attempt to prevent immodest or potentially scandalous displays, however, the contest organizers had specifically prohibited what they described as “tramp, blackface, and semi-nude” outfits.

As the crowd watched the young dancers swivel and twist with manifold permutations of the basic “Charleston” steps, the local and individual character of the dancers became increasing conspicuous. Some were restrained and some wild; some were graceful and some frenetic. Judging what qualified as “best” among such a diverse field was going to be a difficult task, and such judgments were bound to provoke controversy. Not surprisingly, the home-town press was biased in favor of the Charleston couple, whose steps ostensibly represented the style of “Charleston” endorsed by the city’s conservative white arbiters of taste. Manning J. Rubin’s report for the Evening Post provides a colorful example of that local perspective:

“The ‘Charleston’ seemed to be susceptible of an infinite number of variations. They [Annie McCarrel and Sidney Kilpatrick] realized at once that the standard if a standard could be applied was not that which prevailed in the City-by-the-Sea. . . . Bewildering action featured much of the performance[,] and the steps by Mr. Kilpatrick and Miss McCarrel stood out distinctly. They were nimble without being meteoric, maintained perfect poise and precision, gracefully stepped and turned and moved to the rhythm of music rendered by one of the finest dance orchestras in the country. The lightning like evolutions of most of the dancers and the almost athletic prancing which made up much of their variations made it impossible for them to bring out the more graceful possibilities of the dance as interpreted by the couple from Charleston, but their skill and ingenuity and ability to keep up with the lively music was an interesting show. There was no vulgar dancing. It was all zestful, vigorous and undoubtedly expressive of the pep, energy and spirit of young America.”

The Charleston reporters on hand opined that Annie McCarrel wore the most elegant and tasteful frock of all the female contestants, and that she and Sidney Kilpatrick had danced with “exquisite grace.” Their rendition of the popular “Charleston” dance, said Manning Rubin, was “without question the stateliest appearance on the ball room floor.” The Charleston couple displayed vim and gaiety in their “eccentric” dancing, too, but in this more flamboyant variation, they were most definitely outdone by the “bewildering” energy of their competitors.

The dancing ended sometime after midnight and all eyes in the Trianon turned to the judges: Ivan Tarasoff, formerly of the Russian Imperial Ballet, Armand T. Nichols, director general of the Miss America Pageant, Frank E. Piper, treasurer of the American National Association of Dance Masters, and Adelaide Fogg, well-known dancing teacher from Omaha. Their criteria for judging the ballroom dance focused on poise, grace, and rhythm, to which they added “originality of steps” for the “eccentric” dancing.

After receiving the written results from the judges, Harold Murphy spoke through a microphone to announce the four regional winners and summoned Mayor Thomas P. Stoney to deliver the prizes. The couple from Memphis won the Southern division; the pair from Wichita won the Western; Chicago the Northern; and a couple from Petersburg, Virginia, won the Eastern division.

The mayor congratulated each of the regional champions “with fine wit and taste,” and his jovial demeanor with the winners earned “quite an ovation” from the audience. Although the contestants from Charleston did not capture any honors during the first night of competition, Mayor Stoney was clearly jazzed-up by the energy on display throughout the evening. Invoking the spirit of the city that inspired the name of the popular dance, Charleston’s mayor told the crowd, “we have a live town and we have sent you a live dance.”

After the crowd dispersed early Tuesday morning, the home-town reporters at the scene wired their stories back to the Palmetto City. The Charleston couple had danced flawlessly, they proudly announced, and the entire Charleston delegation was “delighted with their showing” in the regional competition. While a few unnamed parties among the Lowcountry visitors were upset with the judges’ choice of Southern champions, Mayor Stoney advised them to relax and enjoy the attention. “No matter who wins, said the mayor, “Charleston wins.”[2]

Tuesday, February 9th: The National Championship:

Following an exhausting week of nearly non-stop dancing, preparations, and travel, Annie McCarrel and Sidney Kilpatrick probably slept late into the morning after the regional competition. The stress resulting from the last-minute truncation of their five-minute dance routines might have spoiled their rest, however, and induced them to rise early. In the hours before the commencement of Tuesday’s competition, the Charleston couple found time to practice at the hotel. With the help of dance coach Jack Simmons, they whittled their best choreography down to two brief minutes for both the ballroom and stage versions of the “Charleston” dance.

Similarly, Mayor Stoney was trying to recover his voice in preparation for a Tuesday evening radio address. He had been suffering from bronchitis before departing from Charleston, but his voice had improved sufficiently to deliver a lunch-time speech at a Chicago business club on Monday. After another business lunch presentation on Tuesday, he returned to the hotel to rest and save his voice for the important promotional speech scheduled for 10 p.m. broadcast.

Similarly, Mayor Stoney was trying to recover his voice in preparation for a Tuesday evening radio address. He had been suffering from bronchitis before departing from Charleston, but his voice had improved sufficiently to deliver a lunch-time speech at a Chicago business club on Monday. After another business lunch presentation on Tuesday, he returned to the hotel to rest and save his voice for the important promotional speech scheduled for 10 p.m. broadcast.

Back in Charleston, members of City Council and other city staff were eager to hear Mayor Stoney’s voice streaming across the national airwaves. Radios were still a relatively new invention in 1926, and the bulky machines of that era required some skill to set up and operate. To satisfy their collective anticipation, the city government hired a local electrical supplier to install and fine-tune a “large radio receiving set” in City Council chambers. The signal broadcast from the Trianon ballroom in Chicago was to be relayed by other stations across multiple states, enabling Charleston’s elected leaders to hear the mayor’s voice through the air waves from nearly 800 miles away.

As show time approached on Tuesday evening, thousands of dance fans from across the United States streamed from Chicago’s snow-filled streets into the Trianon ballroom to witness the first-ever national “Charleston” dance competition. Reporters and photographers from dozens of news outlets were on hand to document the event, as were a number of cameramen shooting moving-pictures for national newsreels. One eyewitness estimated the crowd within the vast ballroom included five thousand spectators, and that number might represent only a slight exaggeration.

At 10 p.m. on Tuesday evening, Charleston Mayor Thomas P. Stoney was the center of attention at the Trianon ballroom. The house audience and unseen listeners across the nation heard a twelve-minute speech about Charleston. In his remarks, which were reprinted in the Charleston Evening Post, Stoney emphasized the charm and beauty of Charleston and the surrounding Lowcountry. He noted the city’s literary and cultural achievements, past and present, and bragged about the commercial potential of the port and industrial facilities. Although not a historian, the mayor took the opportunity to present a sort of municipally-approved narrative of the origin of the “Charleston” dance. This brief chronicle, probably assembled by his staff, contains a bit of the bogus story Grace Jackson had fed to the Chamber of Commerce a few months earlier (see Episode No. 167), mixed with a bit of the broader story of the Great Migration (see Episode No. 166). The result was a slightly contradictory fable, tainted by the racial prejudice so typical of Southern politicians of that era:

“The basic steps and rhythm of the ‘Charleston’ were executed in our city many years before they were developed into the now popular ball room dance. Year after year tourists visiting Charleston found amusement in watching young negroes on the waterfront indulging in their inimitable performances which were later to evolve into one of the prettiest and most pleasing of social dances. These negroes possessed an inborn capacity for their peculiar dance, brought to this country by primitive ancestors in the early days of America. Thus you see everything has its compensations. If the negroes hadn’t come to America, we wouldn’t have had the War Between the States, perhaps, but we wouldn’t have had the ‘Charleston,’ either. At any rate, what the tourists saw on our waterfront was a genuine folk dance in which the negro gave expression to his soul and to his temperament. When, after the World war, many negroes from the south moved to the north, emigrants from Charleston carried their characteristic dancing to Harlem, in New York, and thence it spread to Broadway and, in its refined and modified form, became generally popular in homes and ball rooms.”[3]

After the mayor’s radio address, the photographers and newsreel cameramen took their position in the center of the giant ballroom. The competitors danced on a stage only slightly elevated above the audience, so the cameramen found it difficult to see the action. To improve their vantage point, the management placed several tables in the center of the ball room on which the cameramen and their cameras perched over the crowd and dancers.

Prior to the official competition, the organizers of the event invited the four dancers from Charleston to give a ten-minute feature performance. The purpose of this pre-game display, said Manning Rubin, was “to exhibit how the ballroom and eccentric forms of the new dance were executed in the city in which it originated.” Master of Ceremonies Murphy introduced Annie McCarrel and Sidney Kilpatrick, who glided across the floor alone for five-minutes of ballroom-style choreography that “invested the dance with dignity and sweetness.” After receiving an ovation from the crowd, they stepped aside as Harold Murphy introduced “Mollie” and Edith Davis. Although not competing in the national contest, Mr. and Mrs. Davis had traveled from Charleston to present an energetic five-minute display of “eccentric” steps. Their originality and athleticism had captivated local audiences several weeks earlier, and the Chicago crowd was likewise delighted by the novelty and energy of their performance.

Prior to the official competition, the organizers of the event invited the four dancers from Charleston to give a ten-minute feature performance. The purpose of this pre-game display, said Manning Rubin, was “to exhibit how the ballroom and eccentric forms of the new dance were executed in the city in which it originated.” Master of Ceremonies Murphy introduced Annie McCarrel and Sidney Kilpatrick, who glided across the floor alone for five-minutes of ballroom-style choreography that “invested the dance with dignity and sweetness.” After receiving an ovation from the crowd, they stepped aside as Harold Murphy introduced “Mollie” and Edith Davis. Although not competing in the national contest, Mr. and Mrs. Davis had traveled from Charleston to present an energetic five-minute display of “eccentric” steps. Their originality and athleticism had captivated local audiences several weeks earlier, and the Chicago crowd was likewise delighted by the novelty and energy of their performance.

Following these brief exhibitions, the second night of competition finally commenced. To select one couple as the best amateur “Charlestoners” in the nation from a field of twenty-eight pairs, the contestants repeated their respective two-minute routines, two couples dancing at a time, through a series of four elimination rounds. As the field became smaller in each round, the dancers increased the pace of their steps. According to some eyewitnesses, “many danced like mad.” The couples succeeding through the rounds repeated their prepared choreography with ever increasing speed as a new day dawned outside. As Charleston reporter Henry F. Cauthen observed, the night drew towards a climax with many dancers displaying “frantic efforts to outdo the others.”

“Miss McCarrel and Mr. Kilpatrick danced the ballroom ‘Charleston’ as it is danced in Charleston, with grace and perfect technique. It is as different from the ballroom ‘Charleston’ danced by the others as day and night, and infinitely prettier. But sensationalism is the thing up here. . . . At the very beginning on Monday night, it was evident that they [Miss McCarrel and Mr. Kilpatrick] were alone in their idea of the dance. All of the other couples, without a single exception, indulged in many more eccentric antics than the Charleston couple. These antics, often marvelous for their speed, were always lacking in grace. These other dancers of the dance bearing Charleston’s name seemed to have interpreted it as a medium for limitless and uncontrolled and unrestrained acrobatics.”

Annie McCarrel and Sidney Kilpatrick made it through to the third or semi-final round. Here they were eliminated by a young couple from Grand Rapids, Michigan, who proceeded on to the fourth and final round. Although they left the competition in fourth place overall, Annie and Sidney received glowing praise from the rest of the Charleston delegation on hand that night. Mayor Stoney spoke for the entire community when he told home-town dancers “he was delighted that they hadn’t tried to ‘shake themselves to pieces’ in order to win.” “Defeat was far better,” said the mayor, than imitating the “stupid interpretation of some of the dancers, even if this could have brought victory.”

At the end of the final round of competition, the judges announced their decision. Third place honors went to a couple from Clinton, Iowa, while the Chicago pair secured second prize. The winning couple, capturing the title of national amateur champions of the “Charleston,” was a newly-wed couple representing Grand Rapids, Michigan, Jim and Louise Sullivan. Sometime after midnight on the morning of Wednesday, February 10th, Mayor Stoney presented the winners with their engraved loving cups and jewels.[4] Days later, theater audiences across America watched newsreel footage showing highlights from the competition and the mayor’s awards. Thanks to the magic of the Internet, you can find several different versions of these newsreels online today.[5]

At the end of the final round of competition, the judges announced their decision. Third place honors went to a couple from Clinton, Iowa, while the Chicago pair secured second prize. The winning couple, capturing the title of national amateur champions of the “Charleston,” was a newly-wed couple representing Grand Rapids, Michigan, Jim and Louise Sullivan. Sometime after midnight on the morning of Wednesday, February 10th, Mayor Stoney presented the winners with their engraved loving cups and jewels.[4] Days later, theater audiences across America watched newsreel footage showing highlights from the competition and the mayor’s awards. Thanks to the magic of the Internet, you can find several different versions of these newsreels online today.[5]

The Journey Back to Charleston:

After sleeping late on the morning of Wednesday, February 10th, the various members of the Charleston delegation spent the rest of the day relaxing and seeing the sights around snowy Chicago. Mayor Stoney, Chairman Sam Berlin, and their wives departed for New York to conduct further business before heading back to Charleston. Early on Thursday afternoon the dancers and their chaperone boarded a train to Pittsburgh and on Friday morning continued on to the nation’s capital. Arriving in Washington D.C. around midday on Friday, they were greeted at the station by South Carolina Representative Thomas S. McMillan, who escorted them to the capitol building. The young dancers toured both the House and Senate chambers, enjoyed lunch in the capitol commissary, performed a quick dance exhibition in the House office building, and then raced back to the station to catch the 3:15 south-bound train.[6]

At dawn on Saturday morning, a crowd of family and friends gathered at Charleston’s Union Station to greet the returning dancers with cheers and bouquets. Although Mayor Stoney was still in New York, and the mayor pro-tem was under the weather, the City Council still sent an official delegation to pay their respects and to welcome the weary travelers home. After a brief morning rest, the four dancers—Annie McCarrel, Sidney Kilpatrick, and “Mollie” and Edith Davis—reconvened at City Hall at 11 a.m. The city had planned an open-top automobile parade around the town, but the cloudy weather forced them to raise the tops and wave through the windows as they processed through the streets. A bus filled with members of the Citadel Cadet Band blared jazzy dance music as it led the parade around town and provided accompaniment back at City Hall. Before a crowd of city officials and spectators, the four dancers performed an impromptu exhibition on the marble portico, much to the delight of the crowd gathered in Broad Street.[7]

At dawn on Saturday morning, a crowd of family and friends gathered at Charleston’s Union Station to greet the returning dancers with cheers and bouquets. Although Mayor Stoney was still in New York, and the mayor pro-tem was under the weather, the City Council still sent an official delegation to pay their respects and to welcome the weary travelers home. After a brief morning rest, the four dancers—Annie McCarrel, Sidney Kilpatrick, and “Mollie” and Edith Davis—reconvened at City Hall at 11 a.m. The city had planned an open-top automobile parade around the town, but the cloudy weather forced them to raise the tops and wave through the windows as they processed through the streets. A bus filled with members of the Citadel Cadet Band blared jazzy dance music as it led the parade around town and provided accompaniment back at City Hall. Before a crowd of city officials and spectators, the four dancers performed an impromptu exhibition on the marble portico, much to the delight of the crowd gathered in Broad Street.[7]

A week after his return from Chicago and New York, Sam Berlin made a report to the executive committee of the Charleston tourist and convention bureau. The effort to send a delegation to Chicago was a success on two fronts, he explained. First, it provided a valuable vehicle for distributing information about opportunities for tourists, investors, and home-seekers in the Charleston area. Local agents had distributed a large number of copies of their promotional booklet titled The Lure of Charleston, and had given away more than 6,000 color postcards of the gardens at Middleton Place and Magnolia Plantation. The Chicago organizers also distributed more than 51,000 copies of their own publication, Trianon Topics, which featured photographs of the Lowcountry and articles about various aspects of Charleston. Secondly, the local contestants in the featured dance competition had proved to the nation “that the dance which is named after this city and which the country holds to have originated here can be made a graceful and agreeable ball room dance.”[8]

On the first count of Mr. Berlin’s report, most of the community agreed that the Chicago venture had been a success. There had been doubts in January about its value, observed one editorial in the Evening Post, but the magnificent reception that greeted the Charleston delegation at the Windy City made them realize “the vast volume of publicity that is to be obtained for the city by the sea, as a result of having dispatched participants to the national contest at Chicago.” “As an advertising enterprise,” said another editorial, “this engagement must be accounted a brilliant success and to Chairman Samuel Berlin and those who were associated with him in the undertaking and to Mayor Stoney and to Mr. Kilpatrick and Miss McCarrell [sic], who danced so well, the community is under obligations.”[9]

As an enterprise to demonstrate the respectability of the Charleston version of the “Charleston,” however, there were still opponents who criticized the municipal government for participating in the national competition. A conference of Baptist ministers in the greater-Charleston area, for example, adopted a resolution officially condemning both the popular dance and Mayor Thomas P. Stoney. In their opinion, the mayor and other elected officials “ought to be interested in leading the people into higher ideals rather than into immorality.”[10]

In the long run, most people in the Lowcountry of South Carolina viewed Charleston’s participation in the national “Charleston” competition of February 1926 as a successful venture that paid for itself many times over. The Chicago event was itself a grand advertising spectacle created by and for white America. It promoted and celebrated the successful appropriation and adaptation of a cultural phenomenon created by Americans of African descent. By the spring of 1926, the “Charleston” had moved squarely into the mainstream of American popular culture, and its cultural capital was peaking.

For professional dancers like Bee Jackson, it was now even more important to assert her connection to the City of Charleston and her claim to the roots of the dance. Bee and her mother, Grace Jackson, would be passing through Charleston in early April, 1926, and were still interested in receiving praise and publicity from the people of the Palmetto City. Tune in next week, when we’ll see how the Charleston-wise people of Charleston reacted to the arrival of the self-proclaimed Queen of the “Charleston” dance.

[1] An Associated Press story, printed in Charleston Evening Post, 8 February 1926, page 1, “‘Charleston’ Champions Arriving at Chicago,” named thirty-two participating cities: Akron, Canton, Cedar Rapids, Charleston, Chicago, Cleveland, Clinton, Dallas, Davenport, Detroit, Duluth, Excelsior Springs, Fort Wayne, Grand Rapids, Indianapolis, Joliet, Kansas City, Little Rock, McKeesport, Pa., Memphis, Milwaukee, Oklahoma City, Omaha, Peoria, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, St. Paul, Minneapolis, Toledo, Topeka, Tulsa, and Wichita; but a local report, printed in Charleston News and Courier, 9 February 1926, page 1, “Memphis Couple,” named only twenty-seven cities: “Akron, Ohio; Canton, Ohio; Cedar Rapids, Ohio; Charleston, S.C.; Chicago, Ill.; Cleveland, Ohio; Clinton, Ohio; Davenport, Iowa; Detroit, Mich.; Fort Wayne, Ind.; Grand Rapids, Mich.; Indianapolis, Ind.; Joliet, Ill.; Kansas City, Mo.; Little Rock, Ark.; McKeesport, Iowa; Memphis, Tenn.; Milwaukee, Wis.; Omaha, Neb.; Peoria, Ill.; Pittsburg, Pa.; St. Louis, Toledo, Topeka, Kan.; Tulsa, Okla.; Waterloo, Iowa, and Wichita, Kan.” Note that the same paper identified the Eastern division champions as a couple from Petersburg, Virginia.

[2] Evening Post, 8 February 1926, page 1, “‘Charleston’ Champions Arriving at Chicago”; News and Courier, 9 February 1926, page 1, “Memphis Couple Proves to be the South’s Best Dancers”; Evening Post, 9 February 1926, page 1, “Charleston’s Mayor To Radiocast During ‘Charleston’ Contest,” by Manning J. Rubin; Evening Post, 9 February 1926, page 16, “Charleston In Limelight”; News and Courier, 14 February 1926, page 1, “Dance Judges Reject Wild Antics as Not ‘Charleston.’”

[3] News and Courier, 8 February 1926, page 1, “Radio Listeners are Entertained”; Evening Post, 8 February 1926, page 2, “Mr. Stoney’s Radio Address”; News and Courier, 9 February 1926, page 7, “Radio Installed in Council Hall”; Evening Post, 9 February 1926, page 16. “Charleston In Limelight”; News and Courier, 10 February 1926, page 1, “Brother and Sister from Michigan Win National ‘Charleston’ Title”; Evening Post, 10 February 1926, page 1, “Charleston’s Dancers Win Much Attention In Contest At Chicago.”

[4] News and Courier, 10 February 1926, page 1, “Brother and Sister from Michigan Win National ‘Charleston’ Title”; Evening Post, 10 February 1926, page 1, “Charleston’s Dancers Win Much Attention In Contest At Chicago”; Evening Post, 10 February 1926, page 1, “Mayor Believes Participation in Contest Success”; News and Courier, 11 February 1926, page 1, “Charleston’s ‘Charleston’ Ball Room Dance Was Best”; News and Courier, 14 February 1926, page 1, “Dance Judges Reject Wild Antics as Not ‘Charleston.’” Most newspapers of February 1926 incorrectly identified Louise and J. F. Sullivan as siblings.

[5] See, for example, International Newsreel from 1926 and an excerpt from America Dances! 1897–1948.

[6] Evening Post, 11 February 1926, page 1, “Charleston’s Delegation Now Homeward Bound”; Evening Post, 12 February 1926, page 1, “Charleston Party Is Entertained By Congressman”; News and Courier, 13 February 1926, page 1, “ ‘Charleston Is Done In Capitol.”

[7] Evening Post, 13 February 1926, page 2, “Dancers Are Welcomed”; News and Courier, 14 February 1926, page 2, “Give Exhibition of ‘Charleston.’”

[8] Evening Post, 20 February 1926, page 12, “Chairman Makes Report”; News and Courier, 27 February 1926, page 3, “Mistake as to Number.”

[9] Evening Post, 9 February 1926, page 16, “Charleston In Limelight”; Evening Post, 12 February 1926, page 4, “Did ‘The Charleston’”

[10] Evening Post, 15 February 1926, page 2: “Condemn the ‘Charleston.’”

PREVIOUS: Who Were the Best “Charlestoners” in Jazz-Age Charleston?

NEXT: Bee Jackson’s 1926 Visit to Charleston: Behind the Scenes

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments