Remembering Charleston’s Liberty Tree, Part 1

Processing Request

Processing Request

Charleston’s Liberty Tree is an important part of the story of the American Revolution in South Carolina. As a venue for both weighty political debates and patriotic celebrations, it appears as a relatively minor character in the general narrative of the political activities that transpired here between 1766 and 1780. Nearly every published history of the Revolutionary War in this state mentions the Liberty Tree, but none have focused on this topic exclusively. Today we’ll examine both the roots of its symbolic meaning and its role in the journey to independence.

The idea of using a living tree to represent the abstract concept of liberty may or may not be related to the liberty pole, an ancient symbol that dates back to Roman times. In the semiotic vocabulary of earlier centuries, a wooden pole surmounted by a Phyrigian or “liberty” cap represented liberation—the transition from slavery to freedom. In the political rhetoric surrounding the American Revolution, various orators and essayists evoked this image in conjunction with the upright trunk of living trees. Images of roots and branching limbs inspired metaphors describing the stable trunk of liberty rooted in American soil and supporting many branches representing the various interdependent colonies. The symbolic liberty tree was, like its natural counterpart, a living entity that required care and maintenance. As Thomas Jefferson famously wrote in 1787, “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots & tyrants.”[1]

The Stamp Act Crisis of 1765–66:

The roots of the liberty-tree tradition in British North America are planted firmly in the protests against the so-called Stamp Act of 1765. In March of that year, the British Parliament ratified an act that required American colonists to pay extra duties (taxes) on a wide variety of common paper documents, from court records to newspapers to playing cards. The purpose of the act was to help reduce the British national debt after a long and expensive war with France (the Seven Years’ War), but American colonists objected to the act because they were not consulted at any point during its formulation. The Stamp Act did not become effective until November 1st, 1765, but protests against it commenced in various colonies in the preceding months. The now-familiar cry of “no taxation without representation” was first heard during this era, and like-minded protesters from Charleston to Boston began exchanging information to coordinate their respective protests. That spirit of cooperation led to the first inter-colonial congress held in New York in October 1765, to which South Carolina sent three delegates to confer with other regional representatives. The so-called Stamp-Act Congress wielded no political power, but it helped to solidify opposition to the Stamp Act among the North American colonies. As a result of that coordinated, inter-colony resistance, the British Parliament repealed the offending act in March 1766.

The roots of the liberty-tree tradition in British North America are planted firmly in the protests against the so-called Stamp Act of 1765. In March of that year, the British Parliament ratified an act that required American colonists to pay extra duties (taxes) on a wide variety of common paper documents, from court records to newspapers to playing cards. The purpose of the act was to help reduce the British national debt after a long and expensive war with France (the Seven Years’ War), but American colonists objected to the act because they were not consulted at any point during its formulation. The Stamp Act did not become effective until November 1st, 1765, but protests against it commenced in various colonies in the preceding months. The now-familiar cry of “no taxation without representation” was first heard during this era, and like-minded protesters from Charleston to Boston began exchanging information to coordinate their respective protests. That spirit of cooperation led to the first inter-colonial congress held in New York in October 1765, to which South Carolina sent three delegates to confer with other regional representatives. The so-called Stamp-Act Congress wielded no political power, but it helped to solidify opposition to the Stamp Act among the North American colonies. As a result of that coordinated, inter-colony resistance, the British Parliament repealed the offending act in March 1766.

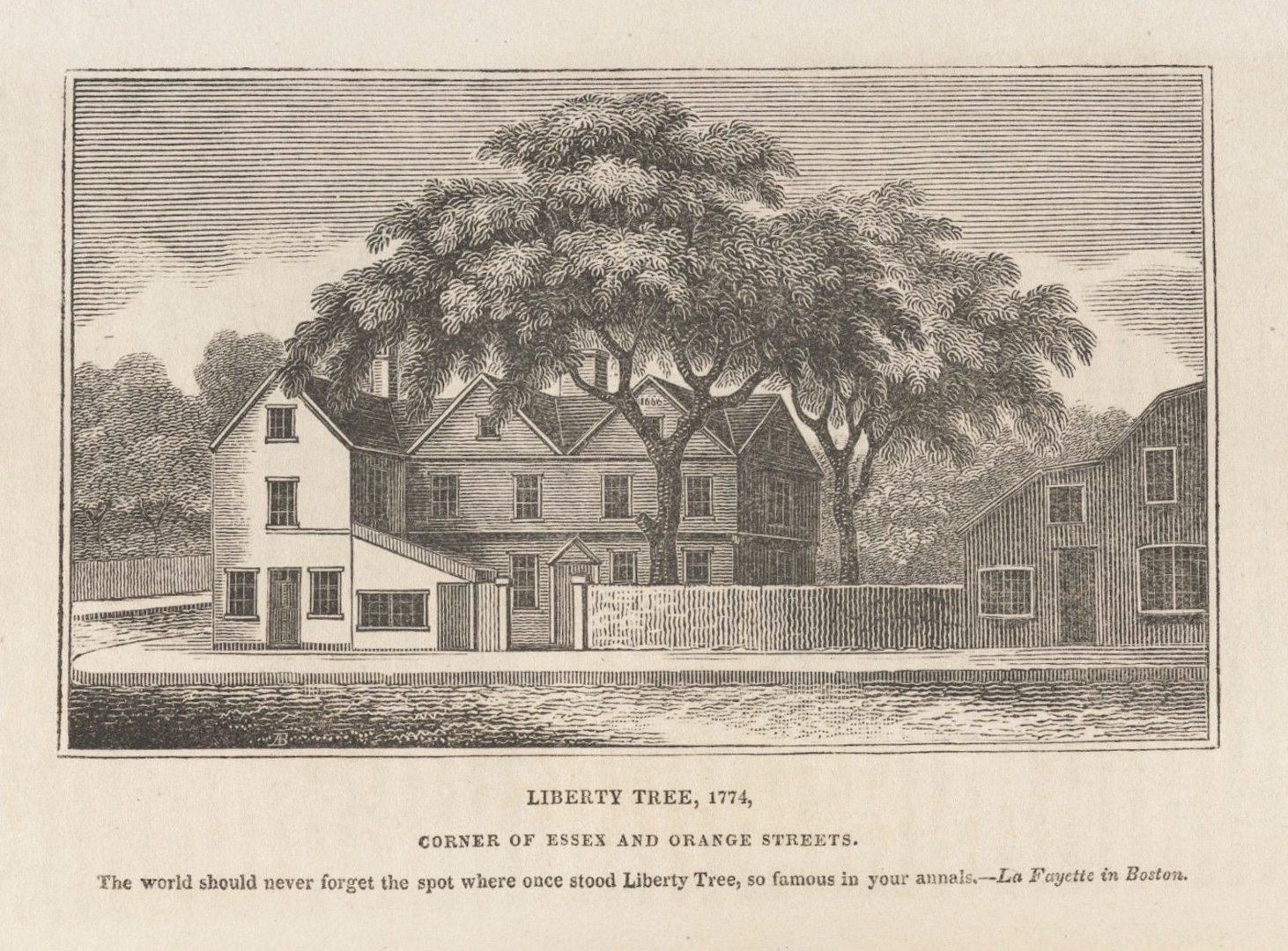

The earliest public demonstrations against the Stamp Act occurred in Boston, Massachusetts, in the late summer of 1765. There, on 14th of August, a group of angry citizens created effigies representing the heavy-handed British government and hung them from the branches of an old elm tree on the south side of the town. There followed a day of revelry and demonstration in which protesters demanded liberty from callous tyranny. When news of a change in government arrived from London a few weeks later, joyous patriots returned to the same elm tree and celebrated their hope for political deliverance. On September 11th, anti-Stamp-Act demonstrators affixed to the elm tree a large copper plaque with gold letters declaring it “the Tree of Liberty.” When news of the parliamentary repeal of the Stamp Act arrived in the spring of 1766, Boston revelers returned to their Liberty Tree, as it became known, and continued to meet at that site in subsequent years to celebrate a variety of patriotic occasions.[2]

The like-minded citizens of Charleston, South Carolina, learned about the proceedings in Boston through private correspondence and public newspapers. We had our own protests and political drama here in the Palmetto City, of course, and even hung our own mock execution of effigies in the middle of Broad Street in the mid-October, 1765. Similarly, there was much rejoicing and a bit of fisticuffs in the capital of South Carolina when news of the Stamp Act’s repeal arrived here in early May 1766. The surviving documents of that turbulent era contain no references to the existence of a Liberty Tree in Charleston, however. That ancient tradition, resuscitated by our Boston compatriots, was adopted later, but the precise timing of its debut has been obscured by the passage of time.[3]

In the months and years after the repeal of the Stamp Act, a number of communities in various American colonies, from Massachusetts to Georgia, adopted liberty trees or liberty poles that served as gathering places for locals to meet and discuss politics. The contentious Stamp Act of 1765 proved to be just the first in a series of British laws that raised the ire of American colonists. A continuing spirit of interdependence helped them to coordinate successful American opposition to the various Townshend Acts of 1767–68 and to battle the Tea Act of 1773 and the Intolerable Acts of 1774. The road to armed revolution in 1775 was paved by a decade of political agitation across the thirteen colonies, and much of it took place under the canopies of a number of Liberty Trees spread across the American landscape.

Autumn 1766: The First Meeting:

At some point in the autumn of 1766, sometime after the repeal of the Stamp Act, a group of twenty-six men gathered under the branches of an ancient live-oak tree just outside of urban Charleston to share a light meal and discuss weighty political matters. It was a private event, devoid of pomp or pretension, and its proceedings did not garner the attention of the local press or nosey journalists. The exact date of the event was later forgotten by those present. The only record of this seemingly inauspicious meeting is a few sentences of text that follow a list of twenty-six names penned around the year 1820, by the last surviving participant, George Flagg (1741–1824). The name of Christopher Gadsden (1724–1805), a famous firebrand of the American Revolution, appears at the head of the list, followed by twenty-five names of lesser renown. Considering the great importance of this brief document, the explanatory text merits a full reading:

On this occasion the above persons invited Mr. Gadsden to join them, and to meet at an oak tree just beyond Gadsden’s Green [Ansonborough], over the Creek at Hampstead, to a collation prepared at their joint expense for the occasion. Here they talked over the mischiefs which the Stamp Act would have induced, and congratulated each other on its repeal. On this occasion Mr. Gadsden delivered to them an address, stating their rights, and encouraging them to defend them against all foreign taxation. Upon which joining hands around the tree, they associated themselves as defenders and supporters of American Liberty, and from that time the oak was called Liberty Tree—and public meetings were occasionally holden [sic] there.[4]

Beginning in 1821 and continuing to the present, a number of historians have repeated George Flagg’s description of this 1766 meeting, with varying degrees of accuracy, and cited it as the earliest-known record of a gathering at the site that became known as “Liberty Tree” (not “the Liberty Tree”). The authenticity of Mr. Flagg’s ca. 1820 memorial was attested by two brothers, Supreme Court Justice William Johnson (1771–1834) and Dr. Joseph Johnson (1776–1862), who knew George Flagg personally and whose father had dined with him at the celebrated event in 1766, so we have little reason to suspect its accuracy. Nevertheless, the Johnson brothers, both published authors, introduced a subtle change to Flagg’s brief story that has effectively derailed part of the larger narrative of Revolutionary activity in pre-war Charleston.[5]

Beginning with William Johnson’s 1822 biography of General Nathaniel Greene and continuing in nearly all subsequent versions of this story, historians have asserted that Christopher Gadsden organized the 1766 meeting under Liberty Tree and invited twenty-five like-minded colleagues to join him. In fact, however, George Flagg’s ca. 1820 memorial clearly states that a group of twenty-five men organized the event and “invited Mr. Gadsden to join them.” As nineteenth-century writers sought to fashion heroes out of various men and women who participated in the American Revolution, it seemed natural to believe that Gadsden, well-known as an energetic advocate of American independence, had organized the 1766 event to “harangue” and indoctrinate some of his peers. But it appears the opposite might have been the case.

Beginning with William Johnson’s 1822 biography of General Nathaniel Greene and continuing in nearly all subsequent versions of this story, historians have asserted that Christopher Gadsden organized the 1766 meeting under Liberty Tree and invited twenty-five like-minded colleagues to join him. In fact, however, George Flagg’s ca. 1820 memorial clearly states that a group of twenty-five men organized the event and “invited Mr. Gadsden to join them.” As nineteenth-century writers sought to fashion heroes out of various men and women who participated in the American Revolution, it seemed natural to believe that Gadsden, well-known as an energetic advocate of American independence, had organized the 1766 event to “harangue” and indoctrinate some of his peers. But it appears the opposite might have been the case.

The twenty-five men who invited Christopher Gadsden to dine with them in the autumn of 1766 were then collectively known as “mechanics.” That is to say, they were skilled tradesmen such as blacksmiths, carpenters, wheelwrights, coopers, tailors, shipwrights, and so on, who made their living by laboring with their hands and tools. As Richard Walsh noted in his 1959 book, Charleston’s Sons of Liberty, the mechanics of Charleston had formed the Fellowship Society in 1762 as a means of protecting the interests of their middle-class members, and the names of the men who dined under Liberty Tree in 1766 with Christopher Gadsden correspond to the membership roll of that venerable society.[6]

These tradesmen stood in contrast to the other two major socio-economic groups in colonial-era Charleston, the merchants and the planters. Left to their own devices, these three groups tended to keep their distance from each other, but the economic trials caused by the Stamp Act, Townshend Acts, and Intolerable Acts convinced them of the necessity of coordinated action. The mutual cooperation among Charleston’s mechanics and merchants and Lowcountry planters in the late 1760s and early 1770s contributed greatly to the success of their protests and kindled the spark of revolutionary spirit in 1775.

Christopher Gadsden was in 1766 a successful middle-aged merchant aspiring to become a planter and ascend the social ladder. Having represented South Carolina in the New York Stamp-Act Congress of 1765 and having protested loudly against the stamps in Charleston in the spring of 1766, Gadsden demonstrated an uncommon vigor for asserting the rights and liberties of American colonists. It appears that the local mechanics saw in him a potential ally, someone who might be sympathetic to the working man’s plight and form a bridge between them and the elitist planters of the Lowcounty. Furthermore, Gadsden’s house was only 900 feet from the oak tree where they planned to gather, so the invitation extended to him in the autumn of 1766 presented no great travel hardship.

Whatever the circumstances surrounding that obscure meeting under Charleston’s Liberty Tree, we know that it bore some important fruit. George Flagg’s brief memoir of the event mentioned a collation, or light meal, which was apparently shared to “congratulate each other” on the recent repeal of the dreaded Stamp Act. To call it a celebration might be too strong a word, but the spirit of the event was apparently meant to be convivial and relaxed. To this scene of bucolic mirth, Christopher Gadsden, recalled Mr. Flagg, supplied a speech that sobered their minds to the coming storm. Many writers have asserted that Gadsden drew their attention to the preamble of the British act that repealed the Stamp Act, but no such preamble exists. Such references no doubt intend to invoke the so-called “Declaratory Act” of March 1766, which underscored Britain’s right to adopt whatever measures it felt necessary to keep the American colonies in a state of dependence. Gadsden apparently warned his neighbors that the repealed Stamp Act would likely be followed by similar attempts to abridge the freedom of American colonists, and implored them to maintain their vigilance. “Upon which[,] joining hands around the tree,” recalled George Flagg, “they associated themselves as defenders and supporters of American Liberty.” This improvised act of political unity, recalled by an aged participant more than fifty years after the fact, represents the genesis of the cooperative spirit that eroded class barriers and fueled the future success of the American Revolution in South Carolina.[7]

The “Association” of 1768–70:

Between the summer of 1767 and the summer of 1768, the British Parliament ratified a series of five laws that circumscribed the traditional rights and freedoms enjoyed by British subjects in North America. Each of these so-called Townshend Acts, named for their proposer, Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer, immediately sparked angry protests in the colonies. In February of 1768, the Massachusetts House of Representatives issued a circular letter to the legislative assemblies of the other colonies complaining about the unconstitutional nature of the Townshend Acts. Lord Hillsborough, Secretary of State for the Colonies, ordered the assembly to rescind the letter. By a vote of 92 to 17, the members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives voted to disobey the order and “not rescind” the circular letter. Governor Francis Bernard then dissolved the assembly, which act triggered episodes of mob violence that in turn led to British military intervention.

Between the summer of 1767 and the summer of 1768, the British Parliament ratified a series of five laws that circumscribed the traditional rights and freedoms enjoyed by British subjects in North America. Each of these so-called Townshend Acts, named for their proposer, Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer, immediately sparked angry protests in the colonies. In February of 1768, the Massachusetts House of Representatives issued a circular letter to the legislative assemblies of the other colonies complaining about the unconstitutional nature of the Townshend Acts. Lord Hillsborough, Secretary of State for the Colonies, ordered the assembly to rescind the letter. By a vote of 92 to 17, the members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives voted to disobey the order and “not rescind” the circular letter. Governor Francis Bernard then dissolved the assembly, which act triggered episodes of mob violence that in turn led to British military intervention.

All of this Massachusetts background forms a necessary prelude to the next chapter in the history of Charleston’s Liberty Tree. South Carolinians were equally upset about the measures imposed by the various Townshend Acts, but our community was spared the violence and military impositions that characterized the Boston experience. On October 1st, 1768, reported a local newspaper of the day, “a very numerous meeting of Mechanicks [sic] and other inhabitants of Charles-Town” gathered at a location they described as “Liberty Point.” Another contemporary newspaper identified this now-obscure site as being “in a field adjacent to the rope walks,” which, to my mind, implies the area north of modern Reid Street in Hampstead Village, where James Reid and other men transformed hemp into ropes for the maritime industry. Here the mechanics and other unidentified participants nominated and debated a slate of candidates for the upcoming legislative election who would best represent their interests and join the Massachusetts assembly in protesting against the Townshend Acts.

Having selected candidates to stand in the upcoming election, the crowd of mechanics and others adjourned at five o’clock in the afternoon “to a most noble Live-Oak Tree, in Mr. Mazyck’s pasture, which they formally dedicated to Liberty” and “consecrated by the name of the Tree of Liberty.” In the ensuing hours, the crowd drank a series of “loyal, patriotic, and constitutional toasts” to commemorate “the glorious Ninety-Two Anti-Rescinders of Massachusetts-Bay” and similar themes. They also toasted the efforts of John Wilkes, the English politician who had been jailed in 1763 for criticizing the British government in issue No. 45 of a periodical called The North Briton. “In the evening,” says a local news report, “the tree was decorated with 45 lights, and 45 sky-rockets were fired. About 8 o’clock, the whole company, preceded by 45 of their number, carrying as many lights [candles], marched in regular procession to town, down King-street and Broad-street, to Mr. Robert Dillon’s tavern [at the northeast corner of Broad and Church Streets]; where the 45 lights being placed upon the table, with 45 bowls of punch, 45 bottles of wine, and 92 glasses, they spent a few hours in a new round of toasts, among which, scarce a celebrated patriot of Britain or America was omitted.”[8]

Having selected candidates to stand in the upcoming election, the crowd of mechanics and others adjourned at five o’clock in the afternoon “to a most noble Live-Oak Tree, in Mr. Mazyck’s pasture, which they formally dedicated to Liberty” and “consecrated by the name of the Tree of Liberty.” In the ensuing hours, the crowd drank a series of “loyal, patriotic, and constitutional toasts” to commemorate “the glorious Ninety-Two Anti-Rescinders of Massachusetts-Bay” and similar themes. They also toasted the efforts of John Wilkes, the English politician who had been jailed in 1763 for criticizing the British government in issue No. 45 of a periodical called The North Briton. “In the evening,” says a local news report, “the tree was decorated with 45 lights, and 45 sky-rockets were fired. About 8 o’clock, the whole company, preceded by 45 of their number, carrying as many lights [candles], marched in regular procession to town, down King-street and Broad-street, to Mr. Robert Dillon’s tavern [at the northeast corner of Broad and Church Streets]; where the 45 lights being placed upon the table, with 45 bowls of punch, 45 bottles of wine, and 92 glasses, they spent a few hours in a new round of toasts, among which, scarce a celebrated patriot of Britain or America was omitted.”[8]

Charleston’s Liberty Tree, adopted by the local mechanics as their gathering place in 1766, entered a more public phrase of its career with the celebration of October 1st, 1768. In the ensuing twelve years, Liberty Tree was the venue for a number of important meetings, both formal and informal, where men debated the means of preserving American liberties within the context of British rule, and later debated the path towards securing American independence from Britain. Some of these outdoor meetings were advertised prominently in the local newspapers, while some were reported only after the fact, and some not reported at all. The extant Charleston newspapers provide few details about such events because local readers generally heard such news through word of mouth, while at the same time relying on the press to relay information about Liberty Tree activities in other communities farther away. It’s difficult, if not impossible, therefore, to create a robust timeline of activity at Charleston’s Liberty Tree and a roster of its visitors.

Despite these documentary challenges, a tour through the local newspapers suggests that Charleston’s Liberty Tree reached the zenith of its popularity between the summer of 1768 and the end of 1770. During that period, South Carolinians of different classes were mostly united in their desire to coordinate with neighboring colonies in protest of the so-called Townshend Acts. They celebrated the third anniversary of the repeal of the Stamp Act in March 1769, for example, by assembling at Liberty Tree, enjoying “a handsome entertainment,” drinking toasts “in a most decent and uniform manner,” and marching with twenty-six lighted candles back to town “in regular order.”[9] More significantly, the local mechanics invited their fellow citizens to join them under Liberty Tree on July 3rd, 1769, to plan a more constructive form of protest. That day, the men assembled beneath the broad live-oak canopy debated and formulated a set of resolutions and a “plan of œconomy” to protest the latest round of British duties. The mechanics resolved henceforth to refuse to accept, purchase, or sell any goods imported from Britain, until the offending duties were repealed. A polished draft of their resolutions was prepared on July 4th, 1769, and citizens were invited to visit Liberty Tree to subscribe their names.[10]

Inspired by the mechanics, the collected merchants of Charleston drafted their own non-importation resolutions and worked with the body of tradesmen to create a unified plan. On July 22nd 1769, the local merchants and mechanics gathered at Liberty Tree with a large body of local inhabitants and “country gentlemen” then in town. Christopher Gadsden read aloud the proposed joint resolutions to protest the Townshend Acts, which were immediately adopted as a “General Association” by the unanimous vote of all present. To help enforce the non-importation measures, the merchants appointed a committee of thirteen of their own men, which act inspired the mechanics and planters to do likewise. These three committees of thirteen men each formed a unified “General Committee” responsible for policing a local trade boycott parallel to those instituted in neighboring colonies. By the end of the day, the majority of the white male electorate in the South Carolina Lowcountry had formed a powerful and socially-diverse voting block or “Association.” The boycott to which they committed themselves would bring economic hardship to each and every man, but they pledged to suffer together for the mutual defense of their collective rights. This event was a major step in the creation of social and political ties that would sustain South Carolina during the darkest days of the Revolutionary War, and it all began with a humble meeting under outstretched branches of Charleston’s Liberty Tree. The effusive verses of a lengthy poem by “Philo Patriæ,” published locally in September 1769, praised the live-oak Liberty Tree as the earthly embodiment of celestial grace: “Here Liberty, divinely bright, / Beneath thy Shade, enthrone’d in Light, / Her beaming Glory does impart, / Around, and gladdens ev’ry Heart.”[11]

Inspired by the mechanics, the collected merchants of Charleston drafted their own non-importation resolutions and worked with the body of tradesmen to create a unified plan. On July 22nd 1769, the local merchants and mechanics gathered at Liberty Tree with a large body of local inhabitants and “country gentlemen” then in town. Christopher Gadsden read aloud the proposed joint resolutions to protest the Townshend Acts, which were immediately adopted as a “General Association” by the unanimous vote of all present. To help enforce the non-importation measures, the merchants appointed a committee of thirteen of their own men, which act inspired the mechanics and planters to do likewise. These three committees of thirteen men each formed a unified “General Committee” responsible for policing a local trade boycott parallel to those instituted in neighboring colonies. By the end of the day, the majority of the white male electorate in the South Carolina Lowcountry had formed a powerful and socially-diverse voting block or “Association.” The boycott to which they committed themselves would bring economic hardship to each and every man, but they pledged to suffer together for the mutual defense of their collective rights. This event was a major step in the creation of social and political ties that would sustain South Carolina during the darkest days of the Revolutionary War, and it all began with a humble meeting under outstretched branches of Charleston’s Liberty Tree. The effusive verses of a lengthy poem by “Philo Patriæ,” published locally in September 1769, praised the live-oak Liberty Tree as the earthly embodiment of celestial grace: “Here Liberty, divinely bright, / Beneath thy Shade, enthrone’d in Light, / Her beaming Glory does impart, / Around, and gladdens ev’ry Heart.”[11]

The non-importation “Association” of July 1769 engendered a long series of economic complaints and acrimonious finger-pointing that continued into the final days of the year 1770. Throughout this eighteenth-month period, citizens met periodically at Liberty Tree to discuss the success of their personal sacrifices, to debate the treatment of offending non-subscribers, and to decry the shortcomings of their non-importing brethren in other colonies. Meanwhile, the British Parliament, stinging from this widespread colonial resistance, ratified a partial repeal of the Townshend Acts in April 1770. One by one, the port towns of North America began relaxing their boycotts on imported British goods. Charleston’s “General Association” held on until the end of December, after which life began to return to normal in the Lowcountry of South Carolina.[12]

Prelude to the Revolution:

Before it adjourned from Liberty Tree in mid-December 1770, South Carolina’s “General Committee” resolved to end its boycott on most goods imported from Britain because Parliament had repealed most of the duties the colonists found so offensive. The import duty on tea remained, however, so the General Committee agreed to continue its 1769 resolution not to import that luxury beverage. Other colonies did likewise, and the years 1771 through 1773 passed in the peaceful avoidance of British tea in North America. When the British Tea Act of May 1773 attempted to force American colonists to receive unwanted shipments of that item, colonial protests once again erupted from Boston to Savannah. In response to the famous Boston Tea Party of December 1773, Parliament ratified the so-called Intolerable Acts in 1774 to punish the ungrateful Americans. In early March of that year, Lowcountry residents once again gathered at Charleston’s Liberty Tree for “a general meeting of the inhabitants” to discuss political matters in advance of a new legislative session.[13]

Back in 2018 I created a series of podcast essays about the initial steps towards armed rebellion in Charleston in the spring of 1775 (see Episodes 62–64). During my research for that series, which includes some background about the local political machinations of 1774, I didn’t find any further references to Charleston’s Liberty Tree. Having probed further into the archives for information about that famous tree, I think I have a better understanding of its virtual disappearance from the documentary record in months leading up to the spark of the American Revolution. As a sort of conclusion for today’s program, I’ll try to summarize my thoughts on the role of Charleston’s Liberty Tree in the decade preceding the commencement of the War of Independence.

The earliest-known political meetings beneath its live-oak canopy, as early as 1766, were informal, private, and small. They were organized and hosted by working-class tradesmen who eventually extended a cooperative hand to representatives of the more affluent merchant class. When the merchants and planters joined the humble mechanics at Liberty Tree in 1768 and then formed an “Association” in the summer of 1769, their discussions and cooperative resolutions were strictly extra-legal, and took place at a venue quite literally and appropriately outside the traditional halls of political discourse. As the path towards independence became clearer in the second half of 1774 and early 1775, however, discussions of liberty and political action moved into the mainstream of public discourse. Emboldened by a decade of protesting against various British transgressions, rebellious citizens met in July 1774 within the Exchange building—a place representing British authority—to voice their grievances. Members of the legitimate South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, meeting in the State House, used that official venue to form the extra-legal South Carolina Provincial Congress in January 1775. In March of 1776, that shadow assembly morphed into the South Carolina House of Representatives, which adopted a new constitution, elected its own president, and declared its independence from Great Britain.

Charleston’s Liberty Tree was, in a manner of speaking, a training ground for the patriots who engineered the independence of South Carolina. It was a safe place outside the noisy town where potentially seditious ideas could be shared without fear of recrimination. As the chorus of voices clamoring for liberty grew stronger, the crowds assembled beneath that shady bower grew larger. In a series of gradual steps, their conversations about resistance and liberty moved from Charleston’s sub-urban fringes to the political mainstream and eventually occupied the sanctioned halls of legitimate political debate. The humble Liberty Tree was not completely forgotten, however. As a tribute of respect for its sheltering service in previous years, citizens and soldiers of the new Continental Army gathered beneath its hallowed limbs on August 5th, 1776, to hear the declaration of a new and independent nation, the United States of America.

Charleston’s Liberty Tree was, in a manner of speaking, a training ground for the patriots who engineered the independence of South Carolina. It was a safe place outside the noisy town where potentially seditious ideas could be shared without fear of recrimination. As the chorus of voices clamoring for liberty grew stronger, the crowds assembled beneath that shady bower grew larger. In a series of gradual steps, their conversations about resistance and liberty moved from Charleston’s sub-urban fringes to the political mainstream and eventually occupied the sanctioned halls of legitimate political debate. The humble Liberty Tree was not completely forgotten, however. As a tribute of respect for its sheltering service in previous years, citizens and soldiers of the new Continental Army gathered beneath its hallowed limbs on August 5th, 1776, to hear the declaration of a new and independent nation, the United States of America.

Although it might not have been as celebrated as Boston’s famous elm, Charleston’s live-oak Liberty Tree merits our historical attention. Any conversation about South Carolina’s path to independence in 1776 must include some acknowledgement of its important role in that journey. Consider its fate, for example. Having captured Charleston, the capital of South Carolina, in May of 1780, British military forces sought out and purposefully destroyed our Liberty Tree. Next week, we’ll explore the death of this venerable live-oak and follow the trail of clues leading to its long-lost roots.

[1] Thomas Jefferson, in Paris, to William Smith in Paris, 13 November 1787. See the original letter on the website of the Library of Congress.

[2] For more information about the genesis of the Boston Liberty Tree, see Arthur M. Schlesinger, “Liberty Tree: A Genealogy,” The New England Quarterly 25 (December 1952): 437; Vaughn Scribner, “‘They will begin to think their united power irresistible’: The Stamp Act and the Crisis of Civil Society,” Inn Civility: Urban Taverns and Early American Civil Society (2019): 122–23.

[3] For more information about the activities in Charleston surrounding the Stamp Act Crisis of 1765–66, see the newspapers of that era, and Robert Weir, “’Liberty and Property, and No Stamps’: South Carolina and the Stamp Act Crisis” (Ph.D. diss., Western Reserve University, 1966); Maurice A. Crouse, “Cautious Rebellion: South Carolina’s Opposition to the Stamp Act,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 73 (April 1972): 59–71.

[4] R. W. Gibbes, ed., Documentary History of the American Revolution (New York, 1855), 10–11. A more accurate rendering of the list of twenty-six men appears in Joseph Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences Chiefly of the American Revolution in the South (Charleston: Walker and James, 1851), 27–28.

[5] The 1766 meeting of twenty-six men at the Liberty Tree was first mentioned in John Drayton, ed., Memoirs of the American Revolution (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1821), volume 2, page 315; followed by William Johnson, Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene (Charleston: A. E. Miller, 1822), volume 1, page 266. An anonymous note published the day after Mr. Flagg’s funeral, perhaps written by William Johnson, quoted a bit of his text about the Liberty Tree and lamented the passing of the last witness to that event (see in Charleston Mercury, 18 February 1824, page 2, “Liberty Tree”). Dr. Joseph Johnson, brother of Judge William, later reported that he had found Flagg’s brief manuscript among his late brother’s papers, and quoted from it in his own monograph about the Revolution; see Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences, 27–28. Robert W. Gibbes published a transcription of Flagg’s manuscript in the 1855 volume of his Documentary History of the American Revolution, 10–11.

[6] Richard Walsh, Charleston’s Sons of Liberty: A Study of Artisans 1763–1789 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1959), 29–30.

[7] Some modern writers have used the phrases “Liberty Tree Party,” “John Wilkes Party” and “John Wilkes Club” to describe the early revolutionaries who gathered at Charleston’s Liberty Tree, but I have not found such titles in surviving documents created during the 1760s or 1770s. These titles appear to represent a bit of modern literary license, and should not be regarded as the official name of a specific club or political party of the Revolutionary era.

[8] See the local news printed in South Carolina Gazette [hereafter SCG], 3 October 1768 and South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal [hereafter SCGCJ], 4 October 1768.

[9] SCGCJ, 21 March 1769; SCG, 23 March 1769.

[10] SCGCJ, 4 July 1769.

[11] The text of the “General Association” appears on the front page of SCG, 27 July 1769, while the description of the meeting appears on page two; the poem, “On Liberty-Tree,” appears in SCG, 21 September 1769.

[12] Subsequent Liberty Tree meetings definitely occurred on 4 September 1769, 30 January 1770, 12 May 1770, 27 June 1770, 22 August 1770, 3 October 1770, 20 October 1770, 20 November, and 13 December 1770, each of which was either advertised beforehand in the local newspapers or described in subsequent papers. Other meetings, unnoticed by the local press, might have occurred as well.

[13] Walsh, Charleston’s Sons of Liberty, 56–61; a reminder of the Liberty Tree prohibition on tea appeared in the local news on the front page of SCG, 30 May 1771; SCG, 28 February 1774 (Monday), page 2: “Tuesday next, is the day to which the General Assembly of this Province stands prorogued. And Thursday [3 March] is the day on which there is to be a General Meeting of the inhabitants at Liberty Tree.”

PREVIOUS: Juneteenth, Febteenth, and Emancipation Day in Charleston

NEXT: Remembering Charleston’s Liberty Tree, Part 2

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments