Quarantine in Charleston Harbor, 1698–1949

Processing Request

Processing Request

Separating the sick from the healthy has been a part of Charleston’s public health policy since 1698, when our provincial government instituted a quarantine policy unprecedented in the English-speaking world. Over the ensuing two and a half centuries, local authorities enacted a series of evolving and occasionally contentious regulations designed to inspect, monitor, and control the flow of maritime traffic entering this port. More than just a bit of maritime or medical trivia, this experience of quarantine protocol impacted nearly every immigrant and visitor who entered Charleston harbor until 1949.

Today we know that microorganisms like bacteria and viruses can cause a wide range of diseases. That understanding, often called the “germ theory" of disease, emerged from scientific research performed during the second half of the nineteenth century. Prior to that time, most people believed that contagious diseases emanated from infected or polluted air arising from rotting organic matter. According to this “miasma theory,” diseases were transmitted by inhaling impure air, not necessarily by physical proximity to an infected carrier. Despite this flawed understanding, most human cultures around the world have practiced some sort of social distancing to combat the spread of sickness since ancient times. When people exhibited symptoms of a contagious disease such as leprosy or bubonic plague, for example, they were usually isolated from the rest of their community. To maintain their good health, people sought to breath clean air and to avoid inhaling whatever noxious fumes made their neighbors sick.

The isolation of infected people is a re-active health practice, however, and is distinct from the modern pro-active strategy of quarantine. Beginning in various Italian port cities in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, civic leaders required ships arriving from areas known to be infected with disease to wait up to forty days—quaranta dei—before unloading their cargo and passengers. This quarantine, as we call it today, was a preventative measure to ensure that any disease that might be carried onboard the vessels had run its course before the people disembarked and the goods were unloaded. To further limit transmission within quarantined vessels, those who exhibited symptoms of contagious diseases were usually removed and isolated in a separate facility known variously as a lazaret, or lazaretto, or pestilence house, or simply ‘pest house.” Such quarantine practices cost money and delayed commerce, of course, and no doubt led to a degree of frustration among the passengers and merchants awaiting imported goods. Nevertheless, civic authorities deemed such nuisances to be a reasonable price for maintaining public health.

The idea and practice of preventative quarantine spread northward from Italy over the years and eventually came to England. That country experienced mass outbreaks of bubonic plague in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, during which the monarchy had occasionally issued “plague orders” to isolate infected people away from the healthy. Such reactive English strategies for combating epidemics of mass sickness lacked consistency, however, and did little to prevent the arrival of foreign diseases into the country. As international ship traffic increased in the seventeenth century, England and her colonies in the New World began to adopt the Italian model of quarantine. In 1647, for example, the news of a mass mortal sickness in the West Indies induced the executive council of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to order a temporary quarantine. Vessels arriving from that region were obliged to anchor in Boston harbor and wait for a period of time before receiving permission to unload their goods and passengers. The City of London adopted a similar directive in 1665 to combat the arrival of bubonic plague from the Continent, but the novelty of this restrictive measure stunted its success.[1]

The idea and practice of preventative quarantine spread northward from Italy over the years and eventually came to England. That country experienced mass outbreaks of bubonic plague in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, during which the monarchy had occasionally issued “plague orders” to isolate infected people away from the healthy. Such reactive English strategies for combating epidemics of mass sickness lacked consistency, however, and did little to prevent the arrival of foreign diseases into the country. As international ship traffic increased in the seventeenth century, England and her colonies in the New World began to adopt the Italian model of quarantine. In 1647, for example, the news of a mass mortal sickness in the West Indies induced the executive council of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to order a temporary quarantine. Vessels arriving from that region were obliged to anchor in Boston harbor and wait for a period of time before receiving permission to unload their goods and passengers. The City of London adopted a similar directive in 1665 to combat the arrival of bubonic plague from the Continent, but the novelty of this restrictive measure stunted its success.[1]

Around the turn of the eighteenth century, various maritime communities within the English-speaking world began to adopt laws to make preventative quarantine a regular and permanent feature of public health policy. News of a deadly epidemic in the West Indies and in Charleston in 1699, for example, inspired Pennsylvania’s provincial government to enact a quarantine law for the port of Philadelphia in 1700. The British Parliament adopted its first quarantine law in late 1710, following news that bubonic plague was raging throughout the Baltic region, from which Britain imported vast quantities of flax and hemp. The Virginia legislature passed its first quarantine law a decade later, and other American colonies followed suit.[2] It may surprise some to learn that South Carolina was not a follower in this policy trend, but rather a leader.

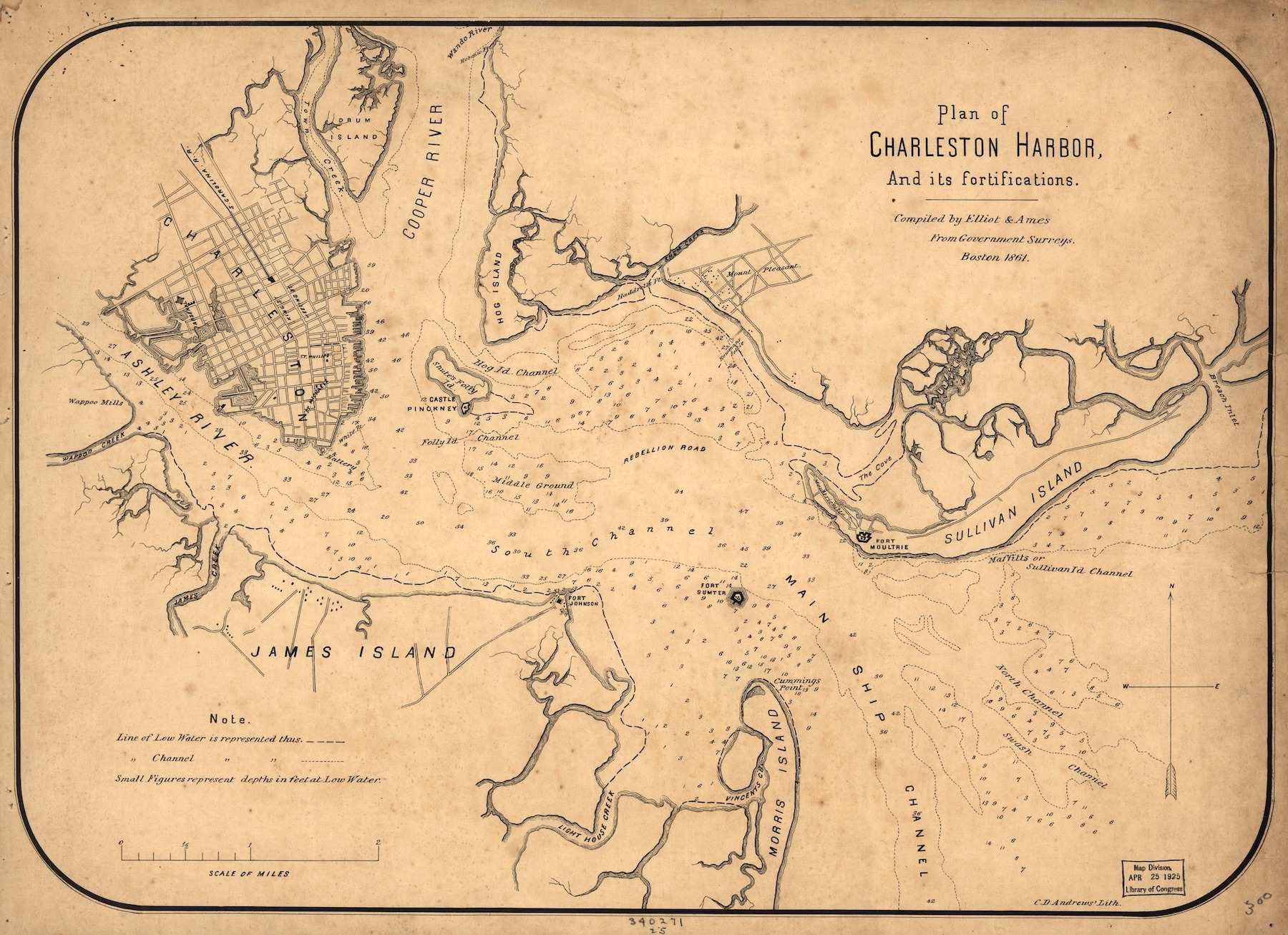

The first step in the creation of a quarantine protocol for the port of Charleston began on October 8th, 1698, when the South Carolina General Assembly updated an earlier statute for creating a public stockpile of gunpowder. The primary purpose of this law was to provide for the defense of the province by requiring all incoming vessels to forfeit a small quantity of gunpowder based on a percentage of the vessel’s tonnage, or cargo capacity. The concern over potential disease vectors was incidental to this important military matter. The eighth section of the 1698 powder law required Charleston’s harbor pilots, while onboard such incoming ships, to “enquire of every master or commander of every vessel whether any contagious sickness be on board his vessel.” If the answer was affirmative, the pilot was required to “acquaint the master not to come above one mile to the westward of Sullivan’s Island.”[3] In other words, vessels carrying people infected with contagious disease were obliged to anchor near the east end of the harbor, approximately three miles from urban Charleston, and await further instructions.

With this simple and relatively vague instruction ratified in 1698, South Carolina inaugurated a maritime quarantine practice that evolved, expanded, and endured over a period two and a half centuries, until the summer of 1949. Charlestonians, like people in other port communities, feared the arrival of “contagious distempers,” by which they principally meant smallpox, but surviving records mentioned other infectious maladies such as bubonic plague, measles, and cholera. After crossing the sandbars that once separated the Atlantic Ocean from the natural harbor of Charleston, every incoming trans-Atlantic, inter-colony, and inter-state vessel immediately entered a legal web of local regulations concerning their movement and possible quarantine. More than two dozen laws were enacted over the years to compel port authorities to inspect, monitor, and, if necessary, detain incoming vessels as well as their crews, passengers, and cargos. Public officials were empowered to use force and arms to ensure a strict compliance with established protocol.

The documentary evidence related to Charleston’s two hundred and fifty years of quarantine policy is sufficient to fill a small book. Rather than bore you with a long-winded chronological summary of that long history, today I’ll simply provide an overview of the most important facts. In future programs, we’ll explore smaller aspects of this important story in greater detail.

From October 1698 to December 1796, quarantine protocol for the port of Charleston was under the administration of the South Carolina General Assembly. The provincial and later state legislatures established policies, appointed agents, and appropriated funds for salaries, expenses, and facilities. The state transferred these responsibilities to the City Council of Charleston in late December 1796, but continued to provide legal support and financial assistance to the city for quarantine enforcement through the summer of 1906. In August of that year, the City Council of Charleston formally transferred these duties to the United States Marine Hospital Service (renamed the U.S. Public Health Service in 1912), while the State of South Carolina continued to own the quarantine facilities (then on James Island) until early 1908. General improvements in health science in the early twentieth century eventually rendered traditional quarantine procedures redundant. On July 1st, 1949, the U.S. Public Health Service ceased quarantine inspections in Charleston harbor. From that point to the present, port authorities have inspected incoming ships while docked at the commercial wharves, without subjecting them to special screenings or segregated quarantine.[4]

Throughout all of this history, Charleston’s quarantine protocol applied to every vessel arriving from any port outside of South Carolina, and to every piece of cargo and every passenger shipped within such vessels—black or white, rich or poor. The vast majority of such vessels were deemed to be healthy and normal. They were permitted to dock at one of Charleston wharves along East Bay Street and to proceed with their commercial business. On the other hand, quarantine law temporarily ensnared incoming vessels carrying people known to be infected with a contagious disease, or suspected of carrying disease, as well as vessels coming from any port recently afflicted with contagious disease. The people aboard such vessels, which formed a small percentage of the total ship traffic entering the port of Charleston, were subjected to an evolving regime of quarantine protocol.

The normative or baseline quarantine protocol in Charleston, as elsewhere, was to require the passengers, crew, and cargo of infected and potentially infected vessels to remain on board while anchored at a designated site within the harbor. The designated quarantine anchorage, or “quarantine ground,” during most of the colonial era was in "Rebellion Road," near the middle of the harbor, around one mile west of Sullivan's Island. After the Revolution, the quarantine anchorage moved to the south side of the harbor, near Fort Johnson on James Island, and was usually marked by yellow buoys. The duration of this quarantine depended on a number of evolving factors and ranged from ten to forty days, during which time the vessel displayed a yellow flag to warn the public.

The normative or baseline quarantine protocol in Charleston, as elsewhere, was to require the passengers, crew, and cargo of infected and potentially infected vessels to remain on board while anchored at a designated site within the harbor. The designated quarantine anchorage, or “quarantine ground,” during most of the colonial era was in "Rebellion Road," near the middle of the harbor, around one mile west of Sullivan's Island. After the Revolution, the quarantine anchorage moved to the south side of the harbor, near Fort Johnson on James Island, and was usually marked by yellow buoys. The duration of this quarantine depended on a number of evolving factors and ranged from ten to forty days, during which time the vessel displayed a yellow flag to warn the public.

Persons on board who were clearly sick could be removed and isolated from the rest in a small lazaretto, but only if appropriate facilities were available on shore to receive them. There were at least ten different lazaretto facilities in Charleston harbor over the centuries, including a succession of four short-lived pest houses on Sullivan’s Island (1707–14; 1745–52; 1755–75; 1784–96), a lazaretto on James Island (1797–ca. 1822) and then three on Morris Island (1776–80; 1826–76; 1876–80), two wooden hulks floating in the middle of the harbor (ca. 1822–26;1865–69), and finally a quarantine hospital at Fort Johnson (1880–1949). The cargo of quarantined vessels was likewise offloaded to quarantine warehouses, when such facilities were available, while the interior of such vessels was “cleansed” with smoke and vinegar.

Speaking of pest houses and Sullivan’s Island, I’ll pause here to say a few words about the intersection of quarantine protocol in Charleston harbor and the ship traffic of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Reliable estimates stemming from generations of diligent research—much of it now encapsulated in the website SlaveVoyages.org—demonstrate that approximately forty percent (40%) of all African captives brought to North America entered this continent through the port of Charleston, South Carolina. In light of the present conversation about quarantine protocol, we can conclude with some certainty that all of the slave ships entering Charleston harbor between 1698 and the end of the trans-Atlantic traffic in December 1807—carrying somewhere between 150,000 and 200,000 people—were subject to review under the local quarantine laws in force during that era. Misunderstandings about the nature of those laws has engendered some misconceptions about the experiences of those enslaved passengers, however. I’ll postpone a more detailed discussion of this story for another time, and offer a summary for the moment.

For most of the period between the advent of quarantine protocol in Charleston in 1698 and the end of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in December 1807, the vessels carrying nearly 1,000 cargoes of people of African descent to this port followed the same quarantine protocol as every other commercial vessel that entered the harbor. If a routine inspection of a slave ship suggested that all aboard were healthy, then the vessel was allowed to proceed to one of the wharves along East Bay Street and to prepare the cargo for sale. If there was reason to suspect the presence of a contagious disease onboard, the vessel and its crowded African passengers were obliged to ride at anchor at the designated “quarantine ground” for a period of days or weeks. If some of the captives onboard were clearly sick, and if an isolation facility was then available, such diseased individuals were removed to the designated pest house or lazaretto on one of the neighboring islands. Following this normative protocol, therefore, only a small percentage of the total number of the African captive who entered Charleston harbor would have set foot on Sullivan’s Island.

Because vessels carrying enslaved people from Africa were frequently suspected of carrying disease, however, South Carolina’s provincial government modified the local quarantine law in 1744 to enforce a more rigid review of all trans-Atlantic slave ships. In theory, at least, all incoming African cargos between 5 July 1744 and 26 March 1784—a period of nearly forty years—were legally required to land their cargos at Sullivan’s Island for a period of ten days prior to sale. When that legal requirement was imposed in 1744, however, a temporary prohibitive duty on imported Africans had actually reduced the traffic to zero during most of the 1740s.[5]

In practice, therefore, the requirement to land all incoming Africans at Sullivan’s Island applied to slave ships arriving during three distinct episodes, extending from the spring of 1749 through December of 1765 (when the traffic legally ceased for three years); from January 1769 through December 1774 (when the traffic again legally ceased), and from the summer of 1783 (when the trans-Atlantic slave trade legally resumed in South Carolina) to late March 1784, when the South Carolina General Assembly adopted a new quarantine law that no longer mandated the landing of all incoming Africans on Sullivan’s Island.[6]

In practice, therefore, the requirement to land all incoming Africans at Sullivan’s Island applied to slave ships arriving during three distinct episodes, extending from the spring of 1749 through December of 1765 (when the traffic legally ceased for three years); from January 1769 through December 1774 (when the traffic again legally ceased), and from the summer of 1783 (when the trans-Atlantic slave trade legally resumed in South Carolina) to late March 1784, when the South Carolina General Assembly adopted a new quarantine law that no longer mandated the landing of all incoming Africans on Sullivan’s Island.[6]

In sum, those three episodes of mandatory slave landings on Sullivan’s Island comprise approximately 23.2 years. Overlaying this figure with the history of the island’s pest houses provides further insight. The second pest house on Sullivan’s Island, built in 1744–45, was destroyed by the hurricane of 1752 and not rebuilt until 1755. That structure was burned on purpose in December 1775 and not replaced until late 1784. During the era of mandatory slave landing on Sullivan’s Island, 1744–1784, newly-arrived Africans would have seen there a small pest house during approximately twelve of the aforementioned 23.2 years.[7]

By presenting these facts, I am not suggesting that the importance of Sullivan’s Island and its pest house(s) within the larger narrative of African-American history is unfounded. Rather, my purpose is merely to suggest that our incomplete understanding of the larger context of quarantine protocol in eighteenth-century Charleston has engendered some inaccurate assumptions about the total number of African captives who set foot on Sullivan’s Island or were sheltered within a pest house before being sold into slavery on the wharves of Charleston. Sullivan’s Island does indeed form an important part of the historical narrative of slavery in North America, but the facts related to the island’s role in the long trajectory of local quarantine protocol merit closer study. I’ll return to this topic in more detail in future programs.

Now, back to our overview of quarantine protocol in Charleston harbor. From 1698 to the turn of the twentieth century, the quarantine protocol for the port of Charleston involved a number of individuals working in concert. Having studied the documentary evidence related to this topic in recent years, I’ve identified seven actors who form the principal characters in this long-running narrative. The first was an agent of an incoming sailing vessel, usually its master or commander, or the ship’s doctor if one was present. On his arrival at the bar of Charleston harbor, he was required to give a sworn statement summarizing the health of all aboard during the journey in question, as well as the health of the port from which they sailed.

The second actor was one of the port’s licensed harbor pilots, experienced mariners whose job was to meet large incoming vessels along the coastline and guide them through the dangerous maze of sand bars that stood between the mouth of the harbor and a point of safe anchorage within. Compelled by law to inquire after the health of the crew, passengers, and cargo of every incoming vessel, the pilots served as the vanguard in the local defense of public health. If a pilot boarded a vessel that was infected with disease or suspected of carrying disease, he was obliged to remain on board, with pay, for the duration of that vessel’s subsequent quarantine.

A third actor was a physician who conferred with the abovementioned agents, inspected suspect vessels and their passengers, and reported his findings to local authorities. Vessels were legally obliged to move into and out of quarantine based on the physician’s report. The physician’s duties (and even a few names) are mentioned in several of South Carolina’s colonial-era quarantine statutes (1712, 1747, 1756, 1759). The port physician reported to Charleston’s City Council from 1797 to 1906, and from 1906 to 1949 he was a Federal employee.

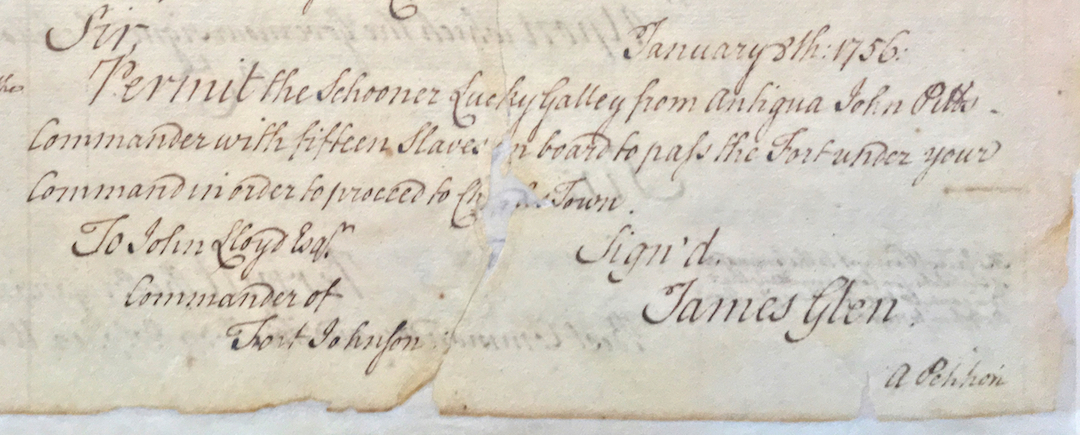

The fourth actor was the commander of Fort Johnson, built in 1708–9 on the north easternmost point of James Island. He was required to monitor ship traffic and to ensure that trans-Atlantic and inter-colony vessels did not enter or depart without proper documentation from the governor and customs officials. Vessels suspected of carrying disease were obliged to ride at anchor “under the guns of Fort Johnson” for a period of time. If a vessel quarantined in this manner attempted to move without permission, or its passengers attempted to come ashore, the commander was authorized to use the fort’s cannons to force their compliance with the law.

A fifth actor, not always in view but always involved on the periphery of the scene, was the commander-in-chief of South Carolina, the governor, or his proxy, the lieutenant governor. Extant documents, especially those from the second half of the eighteenth century, demonstrate that port authorities kept the chief executive abreast of the details concerning vessels performing quarantine. When occasion required, he could exercise the power to order people and/or ships into or out of isolation at the pest house or lazaretto. The governor also issued occasional proclamations instructing the public to avoid quarantined areas inhabited by infected people.

The sixth actor was the custodian of the various isolation facilities successively called the pest house, lazaretto, and quarantine hospital in different generations. This person, usually a poor white man without a family, was a facilities manager rather than a health care professional. His duties included receiving and distributing supplies from the mainland, maintaining the buildings, and safeguarding the storage of quarantined cargo in a warehouse (if one existed). When occasion or necessity required, the custodian communicated with the legislature or City Council to request assistance or to report problems with the facilities under his care.

A seventh actor in the cast of characters populating this historical narrative was, of course, the person(s) subjected to quarantine. Few written records survive from the perspective of those caught within the web of Charleston’s quarantine protocol, but we can at least imagine their thoughts and opinions. A handful of records survive from individuals who either protested their confinement or sought to explain their illegal avoidance of quarantine. Such rare documents provide valuable insight into the experiences shared by thousands of people entering this port in various states of distress.

Quarantine protocol in Charleston harbor, like that of other port communities around the world, represented a continual struggle between the public duties of government and the private interests of commerce. The South Carolina General Assembly and the City Council of Charleston enacted quarantine laws intended to protect the health and safety of the inhabitants in general. Merchants involved in the importation of foreign goods (including enslaved people), on the other hand, sought to bring their cargoes to market as expeditiously as possible. The local government’s quarantine laws occasionally delayed the sale of imported cargos, however, and thus had the potential to reduce or even spoil expected profits. In response to these conditions, merchants involved in the importation of cargos in early Charleston frequently ignored, bypassed, or conspired in various ways to defy quarantine laws in an effort to maximize their profits. The surviving evidence of non-compliance forms an important and valuable tool for understanding local quarantine history.

My goal today has been to provide a brief overview of a broad and complex subject. By tracing the documentary evidence related to these actors and the evolving legal framework that compelled them to act, we can form a more robust picture of the procedures designed to inspect, monitor, and control the flow of maritime traffic through the port of Charleston. This subject, which has received too little attention in the past, is more than just a bit of maritime trivia. Neither is it simply a story of interest to the medical community. Rather, I think it’s important to remember that quarantine protocol was a dynamic “force field” of regulations that impacted the experience of nearly every immigrant and visitor who entered Charleston harbor between 1698 and 1949.

Here in April of 2020, airplanes rather than sailing ships carry most of the newcomers and visitors traveling to Charleston. The coronavirus drama has reawakened our collective appreciation of the concepts of quarantine and isolation, however, and this ancient topic is now relevant again. But this too shall pass, and the people of Charleston—like many thousands before us—will soon emerge from our temporary lazarettos and move on with the business of life.

If you enjoyed this essay, you might like these related stories from the Charleston Time Machine

The End of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade (Episode No. 50 from 26 January 2018)

The Story of Gadsden’s Wharf (Episode No. 51 from 2 February 2018)

Nearly 1,000 Cargos: The Legacy of Importing Africans into Charleston (Episode No. 85 from 5 October 2018)

Commemorating the African-ness of Charleston’s History (Episode No. 99 from 1 February 2019)

The Sales of Incoming Africans on the Wharves of Colonial Charleston (Episode No. 125 from 30 August 2019)

[1] Brock C. Hampton, “Development of the National Maritime Quarantine System of the United States,” Public Health Reports (1896–1970) 55 (July 1940): 1244–45 (of 1241–57); Paul Slack, The Impact of Plague in Tudor and Stuart England (London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1985), 221, 313.

[2] Hampton, “Development,” 1245–46; Charles F. Mullett, “A Century of English Quarantine (1709–1825),” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 23 (November-December 1949): 527–45; Virginia’s first quarantine law was enacted during a legislative session that commenced in November 1720 and concluded in May 1722; see William Waller Hening, The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All of the Laws of Virginia, volume 4 (Richmond, Va.: Franklin Press, 1820), 99–103.

[3] “An Act for the Raising of a Publick Store of Powder for the Defence of this Province,” ratified on 8 October 1698, identified as Act No. 166 in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 2 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1837), 152. This 1698 law was a revision of a similar law ratified on 22 January 1686/7, “An Act for the Raising of a Public Store of Powder for the Defence of this Province,” identified as Act No. 33 in Cooper, Statutes at Large of South Carolina, 2: 20–21.

[4] Act No. 1646, “An Act to amend an Act, entitled ‘An Act to Prevent the Spreading of Contagious Distempers in this State,’” ratified on 19 December 1796, Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 5 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1839), 284–85; Charleston Evening Post, 11 September 1906, page 2, “Federal Quarantine”; Charleston News and Courier, 25 February 1908, page 3, “At the Quarantine Station”; Charleston Evening Post, 1 July 1949, page 1, “Quarantine Station Here to be Closed.”

[5] Act No. 669, “An Act for the better strengthening of this province, by granting to his Majesty certain taxes and impositions on the purchasers of negroes imported, and for appropriating the same to the uses therein mentioned, and for granting to his Majesty a duty and imposition on liquors and other goods and merchandizes, for the use of the publick of this province,” ratified on 5 April 1740, imposed prohibitively-high import duties on incoming Africans in an effort to suppress the trade for a period of time; see Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 3 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1838), 556–68; W. Robert Higgins, “The South Carolina Negro Duty Law” (M.A. thesis, University of South Carolina, 1967), 62–64, 69; George C. Rogers, Jr., Evolution of a Federalist: William Loughton Smith of Charleston (1758–1812) (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1962), 13; Chapman J. Milling, ed., Colonial South Carolina: Two Contemporary Descriptions by Governor James Glen and Doctor George Milligen-Johnston (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1951), 45. The requirement that incoming Africans land first at Sullivan’s Island appears in Act No. 720, “An Act for the further preventing the Spreading of Contagious or Malignant Distempers in the Province,” ratified on 29 May 1744, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 3: 773–74; by way of several legislative extensions, this act was continued in force until May 1784.

[6] Stuart O. Stumpf, “Implications of King George’s War for the Charleston Mercantile Community,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 77 (July 1976): 184. Act No. 933, “An Act for laying an additional duty upon all Negroes hereafter to be imported into this Province, for the time therein mentioned, to be paid by the first purchasers of such Negroes,” ratified on 10 August 1764, imposed a prohibitively high duty on imported Africans from 1 January 1766 to 1 January 1769 to suppress the trade; see Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 4 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1838), 187–88. By signing the Continental Association of October 1774, South Carolina agreed to cease importing African slaves after December of that year. Slave ships returned to Charleston harbor in the late summer of 1783 and continued to arrive until the state of South Carolina imposed a moratorium on the trade in March 1787; see Act No. 1371, “An Act to regulate the recovery and payment of debts; and prohibiting the importation of negroes for the time herein mentioned,” ratified on 28 March 1787, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 5: 36–38. In the meantime, however, the revised quarantine law of 1784 omitted the requirement to land incoming Africans on Sullivan’s Island; see Act No. 1219, “An Act to prevent the spreading of Contagious Distempers in this State,” ratified on 26 March 1784, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 4: 615–18.

[7] Act No. 720 (mentioned above) ordered the construction of a new pest house on Sullivan’s Island in 1744; its destruction in 1752 was mentioned in the South Carolina Gazette, 19 September 1752. The construction of a replacement pest house was ordered by Act No. 826 on 11 May 1754, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 4: 10–12. That structure, in operation by 1755, was burned by South Carolina soldiers on 19 December 1775; see the “The Journal of the Second Council of Safety, Appointed by the Provisional Congress, November, 1775,” in South Carolina Historical Society, Collections of the South Carolina Historical Society, volume 3 (Charleston: by the society, 1859), 103. A replacement pest house was ordered by Act No. 1219 (mentioned above), but was not completed until late in 1784 at the earliest.

PREVIOUS: The Scandalous Black Dance of 1795, Part 2

NEXT: Charleston at 350: The Legacy of Founding Decisions

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments