Planning Charleston in 1672: The Etiwan Removal

Processing Request

Processing Request

Charleston on the peninsula called Oyster Point became the capital of South Carolina in 1680, but plans for the port town commenced nearly a decade earlier. One of the first steps in its creation was an act of displacement ignored by later historians. Like the Dutch colonists who in 1626 purchased Manhattan from Native Americans, English settlers circa 1672 paid Etiwan Indians to abandon the land between the rivers Ashley and Cooper. Details of that long-forgotten transaction are now lost, but valuable clues survive within the sparse written records of early South Carolina.

The story of what we might call the “Etiwan Removal” is an important episode in the history of the Palmetto State, but you won’t find it mentioned in the history books written over the past few centuries. The reasons behind this omission are both simple and lamentable. First, the documentary evidence related to the story is exceedingly thin and has lingered in obscurity within the footnotes of the larger narrative of South Carolina history. Second, the early historians of South Carolina adopted a Eurocentric focus that emphasized the lives and labors of White settlers who, for most of the state’s long history, formed the minority of its population.

The Native Americans who inhabited the Charleston area in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries were largely swept aside by European immigrants who regarded them as “savages.” As I described in Episode No. 220, the numerous Indigenous tribes of the South Carolina Lowcountry faded into obscurity within a few generations after the English settlement of South Carolina in 1670. The task of reconstructing their obscure history requires us to examine carefully minute shards of evidence—both physical and documentary—to identify small details that help us understand a larger picture of the forgotten past.

Part 1: The Evidence:

The evidence related to the movement of the Etiwan people consists of two brief references within documents written some years after the fact. Both of the sources in question pertain to the site of Charles Town on the peninsula between the rivers Ashley and Cooper. The town now called Charleston was not the first English settlement within the present bounds of the Palmetto State, nor the first to be named “Charles Town.” The English colonists who arrived here in the spring of 1670 camped at a peninsula they called Albemarle Point on the west side of the Ashley River. Their initial settlement, named Charles Town in honor of the reigning English monarch, provided a base for immigrants who immediately began exploring the surrounding countryside in search of better accommodations.

The present site of the City of Charleston, rooted on the peninsula between the rivers Ashley and Cooper, was called Oyster Point by the earliest English settlers. Planning for a town on the southernmost portion of the peninsula officially commenced in 1672, and the un-named town at Oyster Point attracted a small number of settlers during the ensuing years. South Carolina’s nascent government officially moved across the Ashley River in the spring of 1680, at which time the un-named town at Oyster Point became “new” Charles Town, and the initial settlement at Albemarle Point became known as “Old Town” (now Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site).

In May 1680, a prominent English settler named Maurice Mathews wrote a brief description of the new site of Charles Town on the Oyster Point peninsula. Mathews had been among the first settlers in the province, a member of its governing Council, and a deputy of the Lords Proprietors in England who owned the Carolina Colony. In short, he was a well-connected man who occupied a position of authority in the earliest days of the English settlement. His 1680 description of Charles Town, which survives only as a flawed copy of a copy of a now-lost letter, includes many unique details about the creation of South Carolina’s new capital, including a brief but valuable discussion of the Native Americans living in close proximity.

Drawing the reader’s attention to geographic features northeast of the peninsula, Mathews pointed to a river he called Ostach—a word corrupted by later copyists, but apparently referring to the river now called the Wando. English colonists had settled “upon three miles up this branch,” said Mathews, but he noted that “the rest of it is allowed [to] our nighbour Indians, ffor wee thought it not justice[,] though with our owne consent[,] and with a valuable consideration payed them too, to remove them from their old habitations without providing for and securing to them a place where they might plant and live confortablie[,] or that any of their former conveniencies of life should be taken from them.”[1]

In other words, Maurice Mathews acknowledged that the English settlers or their provincial government, at some point between 1670 and 1680, paid some body or bodies of Indigenous people to abandon their “old habitations” and move several miles to the northeast. Mathews did not specify the identity of the Natives or the site from which they had removed, but we can deduce the location from the tenor of his letter. Because the bulk of Mathews’s text describes the new town on the peninsula between the rivers Ashely and Cooper, we can surmise that the English paid Indigenous people to abandon the Oyster Point peninsula before colonists established the community that became “new” Charles Town.

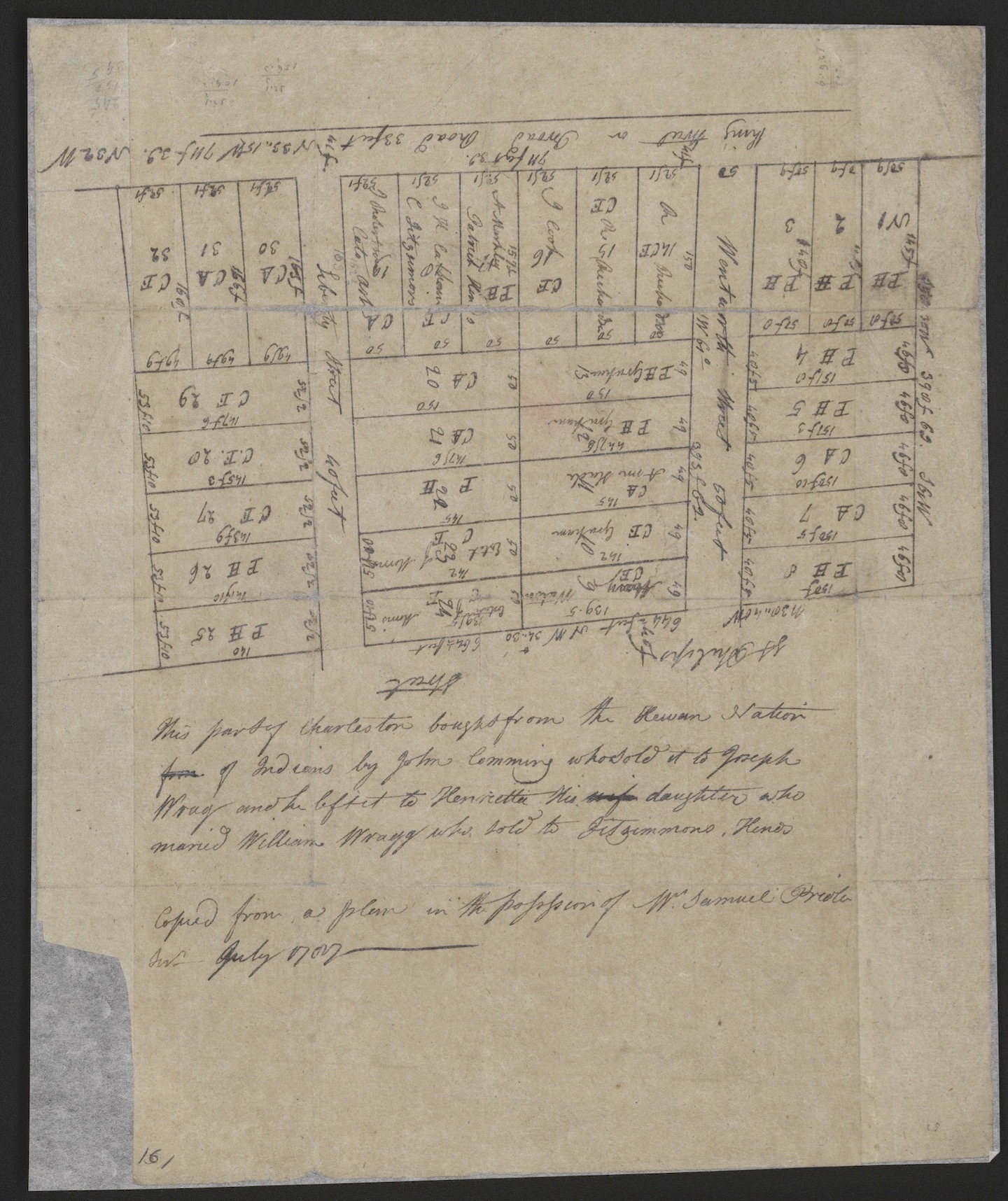

The second piece of evidence in the story of the Etiwan removal dates from a century after Maurice Mathews’s descriptive letter. A small plat or property survey made in 1787, depicting a parcel of six acres within the City of Charleston, contains a brief, handwritten inscription relating to the site’s early history. The document lacks a signature, but the handwriting is clearly that of Joseph Raymond Purcell, the premier surveyor of late-eighteenth-century South Carolina and a reputable source of accurate information. In the summer of 1787, Purcell drew a copy of an earlier plat depicting a subdivision of thirty-two building lots bounded by King Street to the east, St. Philip Street to the west, and bordering both sides of Liberty and Wentworth Streets. Below his illustration of the lots in question, Purcell added the following caption: “This part of Charleston [was] bought from the Itewan [or Hewan; i.e., Etiwan] Nation of Indians by John Comming [sic] who sold it to Joseph Wrag[g,] and he left it to Henrietta his daughter who married William Wragg who sold it to Fitsimmons, [and] Hinds. Copied from a plan in the possession of Mr. Samuel Prioleau in July 1787.”[2]

By combining the data contained within these two sources, we can deduce the following conclusion: At some point between the arrival of English settlers in April 1670 and the removal of Charles Town to its present site in the spring of 1680, English colonists paid the Etiwan Indians to remove from Oyster Point to make room for the creation of a town that became modern Charleston. This brief statement adds a new and important layer to the narrative of Charleston history, but it leaves many questions yet unanswered: Who were the Etiwan? Who paid them to leave Oyster Point, and where did they go? How much money changed hands? When did the transaction or transactions take place? To refine our understanding of this topic, we have to turn back the pages of history to the founding of South Carolina and review the sequence of events leading to the creation of the English town at Oyster Point. The story of the Etiwan exodus is couched within a larger, trans-Atlantic conversation about civic planning in the Carolina Colony.

Part 2: The Initial Settlement at Albemarle Point:

The first group of English settlers bound for South Carolina departed from London in the autumn of 1669 and arrived on the Carolina coastline in the spring of 1670. Instructions from the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, who claimed ownership of the land and financed the expedition, directed them to plant a settlement at Port Royal, near the modern town of Beaufort, South Carolina. That broad harbor was claimed by nearby Spanish colonists, however, who identified the site as Santa Elena lying within the northern part of La Florida. The English colonists found friendly Indians at Port Royal when they arrived in March 1670, but also encountered hostile natives inhabiting the neighboring territory to the south who were allied with the Spanish Floridians.

Fearful of being attacked by hostile Spanish forces or their Native American allies, the English settlers accepted an invitation from a friendlier group of Indigenous people who saw an opportunity to gain protection from their common enemies. The hospitable natives, called the Kiawah, led the settlers to their tribal territory some fifty-odd miles to the northeast of Port Royal, where they found a remote, wooded bluff bounded by a small creek flowing into a bold river that emptied into a commodious natural harbor. That secluded site, which the English named Albemarle Point, became the first foothold in the creation of South Carolina.[3]

Shortly after unloading their ships and constructing shelters in the spring of 1670, the principal officers of the expedition formed South Carolina’s first government, consisting of an appointed executive and his advisory Council.[4] Governor William Sayle and others soon drafted letters to the Lords Proprietors in England to inform them of their location and progress, but their initial descriptions were rather sparse. The colony’s first secretary, Joseph Dalton, had carried a supply of paper on board the frigate Carolina when he embarked from London, but a series of storms during the trans-Atlantic journey soaked most of the paper. As a result of this damage, Secretary Dalton and other officers had very little paper with which to record the early events during the first years of the settlement.[5]

The surviving letters and reports from Charles Town in 1670 credit the Kiawah Indians with suggesting the site of the first English settlement, but those records do not specify whether or not the colonists paid or compensated the Kiawah for the use of their land. It seems likely, however, that the parties in question considered the town site as a sort of gift to the English settlers of South Carolina, since the Indians had invited them to plant on their tribal homeland rather than at Port Royal.

Throughout the remainder of the year 1670, the English colonists focused on planting crops and erecting defensive fortifications around their small settlement at Albemarle Point on the west side of the Ashley River. The local deputies of the Lords Proprietors also granted several large tracts surrounding Charles Town to a number of individuals, but neither the government nor the settlers attempted to create any new towns during the first year and a half of their tenure in South Carolina.

Part 3: Planning Settlements beyond Albemarle Point:

Almost immediately after learning of the creation of Charles Town on Albemarle Point, the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, chiefly Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper (later the first Earl of Shaftesbury), began encouraging the settlers to explore the nearby rivers for other sites suitable for future towns. Lord Ashley, as he was then known, wrote a series of letters to the officers at Charles Towne expressing concern that the settlers might disperse into the woods to pursue their various private endeavors. Ashley was adamant about “the planting of people in townes,” a feature that he believed made the villages of New England more successful than the rural settlements spread across the colony of Virginia. After reading various reports of the landscape of Albemarle Point, Ashley voiced his disapproval of the initial site of Charles Town, a place he understood to be “moorish,” unhealthy, geographically constrained, and irregular in design. Throughout the year 1671, he encouraged the settlers to follow the rivers Ashley and Cooper further upstream “to seeke for a healthy highland, convenient to set out a towne on as high up as a ship can well be carried.” The creation of a commodious port town with a grid of perpendicular streets was Lord Ashley’s civic focus, directing the settlers to begin planning “an exact regular towne on the next river” that could serve as the colony’s principal port and place of trade.[6]

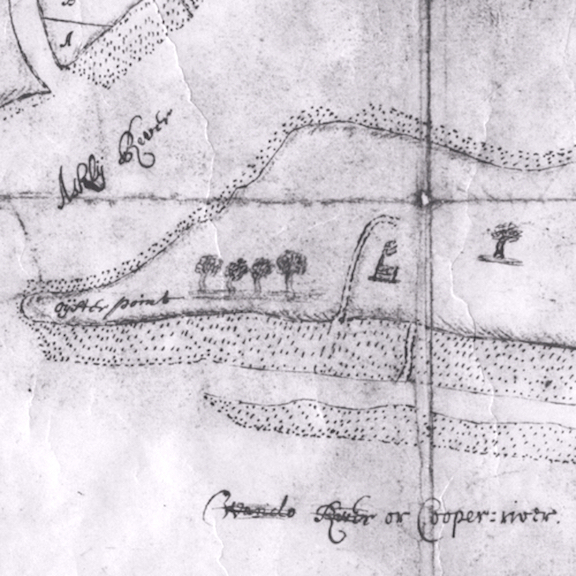

The colonists at Albemarle Point moved closer to fulfilling Lord Ashley’s instructions in July 1671, when newly-elected Governor Joseph West supervised an election to create a new legislative body—a lower house of assembly—that would collaborate with the executive council to form a “Grand Council” for the better governance of South Carolina.[7] Around the time of the new Council’s first meeting in late August 1671, Governor West sent to the Lords Proprietors in England a map or “draught” of the landscape around the nascent English settlement, drawn by Deputy Surveyor General John Culpeper. His “draught,” now preserved at the British National Archives in London, provides the earliest view of both the original Charles Town at Albemarle Point and the peninsula called “Oÿster Point” between the rivers Ashely and Cooper.[8]

In September 1671, South Carolina’s Grand Council began discussing the creation of new settlements for “the better disposing of people that hereafter shall arrive at this place.” Their first priority was to identify potential town sites beyond Charles Town on the Ashley River. In late October, the Council ordered a committee to “goe and view all the places on this river [that is, the Ashley] and Wandow [sic; Cooper] River, and take notice and make a returne of what places may be most convenient to situate towns upon, that soe the same may be wholly reserved for these and the like uses.”[9]

The result of the committee’s exploration is unclear, as their report does not survive. We know, however, that they identified at least one suitable town site before the end of 1671. In December of that year, ships from New York brought a number of immigrants hoping to settle in South Carolina. The provincial government then ordered the surveyor general and his deputies to lay out a small town on James Island, covering just of thirty acres, called James Town, which formed the colony’s second English community.[10]

A few weeks later, after a Christmas recess, the Grand Council resumed the discussion of future towns during a conversation about “the better safety and defence of this province and the severall [sic] persons now or hereafter to inhabitt the same.” On January 13th 1672, the Council ordered a group of men to revisit various sites on the Cooper River “and there marke such place or places as they shall thinke most convenient for the situacon of a towne or townes and their report thereof to returne to the Grand Councill wth. all convenient speed.” To ensure that no settlers would encroach on potential sites identified by the committee, the Council further ordered “that noe person or persons upon any pretence whatsoever doe hereafter run out or marke [sic] any lands on Wandoe [sic; Cooper] River aforesd or in any of the creekes or branches thereof, untill such report be returned by the sd Capt: [John] Godfrey Capt: Thomas Gray and Mr. Maurice Mathews as aforesaid.”[11]

The report of this exploratory committee does not survive, but the participants apparently returned expeditiously with a favorable endorsement of the peninsula called Oyster Point. Seven days after the Grand Council ordered the committee into the Cooper River, on January 20th 1672, Secretary Joseph Dalton wrote a long and glowing letter to Anthony Ashley Cooper describing the proposed town site. He explained that the settlers were generally disinclined to settle further inland, as Lord Ashley had ordered, because of concerns for their own safety. “As it has been the practise of the most skillful settlers,” said Dalton, “so it will become us to erect townes of safety as well as of trade[;] to which purpose there is a place between Ashley River and Wandoo [sic; Cooper] river[, containing] about six hundred acres left vacant for a towne and fort by the direction of the old Governor Coll. Sayle[,] for that it comands both the rivers.”[12]

Joseph Dalton’s letter of January 1672 provides the earliest reference to a reservation not mentioned in previous records. South Carolina’s first governor, William Sayle, died in early March 1671, just eleven months after landing in the colony. At some point between his arrival and his death, therefore, Governor Sayle noted the strategic potential of the peninsula located at the confluence of the rivers Ashley and Cooper, which combine to form a natural harbor leading directly to the Atlantic Ocean. The southernmost point of the peninsula commanded the mouths of the principal rivers and provided a panoramic view of the environs. It was, as Joseph Dalton described, more defensible that any other site in the vicinity, well-suited to the reception of sailing vessels, and sufficiently commodious to host the large and regular town plan favored by Lord Ashley. Governor Sayle seems to have anticipated the colony’s future needs when he directed or ordered, perhaps in an informal fashion, that the southernmost part of this peninsula should be reserved “for a towne and fort.”

Government planning for the creation of a new town at Oyster Point continued through the remainder of 1672, confirming that the site reserved by Governor Sayle and endorsed by Secretary Dalton was destined to become South Carolina’s principal port town at some point in the future. Before that work commenced in earnest, however, the English settlers needed to address an important fact not recorded in the surviving documents of that era: Oyster Point was not uninhabited, and the government had to parley with the Indigenous residents.

Part 4: The Etiwan and their Removal:

At some point during the third week of January 1672, the committee appointed by South Carolina’s Grand Council crossed the Ashley River by boat to Oyster Point. No record survives of their conversation or their actions, but the extant circumstantial evidence suggests a plausible scenario. The committee members—John Godfrey, Thomas Gray, and Maurice Mathews, were familiar with the site after nearly two years residence on the opposite side of the Ashley River. They spent some hours walking the length and breadth of the lower peninsula, and might have conversed with the Native residents they encountered in their path. Having formed a favorable opinion of the land as the site of a future port town, framed by rivers to the southeast and southwest, the men determined a suitable location for the town’s northern boundary. The Council had instructed them to mark the site of their choice, so they selected a prominent tree nearby. At an unknown point, somewhere near the present site of St. Mary’s Catholic Church on the south side of Hasell Street, they cleaved a void or chopped several distinct lines in the tree’s bark. All the land to the south of this “bearing tree,” to use a surveying term, was reserved to the public for a future town, while the land to the north would soon be granted to various individual settlers.

The land was not vacant, however, so the members of the committee, or other agents of the provincial government, negotiated with the resident Natives to secure their consent of the future development. Thanks to the surviving reference inscribed on a 1787 plat, we can identify the Etiwan Indians as the most likely participants in that long-forgotten conversation.

Nothing is known of the origins and early history of the Etiwan People who formerly inhabited the peninsula now home to the City of Charleston. Spanish visitors to Charleston Harbor in 1609 mentioned the Etiwan people living within the vicinity, but did not articulate their precise location. The English colonists who settled at Albemarle Point in 1670 described the Etiwan as one of the “more northerne” groups of Indians; that is, they lived somewhere to the northeast of the Ashley River. As early as 1671, some of the English settlers began describing the river we call Cooper as the “Ittiwan River.”[13]

The identity of the government agent or agents who negotiated and paid the Etiwan is unknown, but that task might have been assigned to the committee appointed by the Grand Council to choose the site for the colony’s port town. That group included militia captains John Godfrey, Thomas Gray, and Maurice Mathews. As I mentioned earlier, Mathews’ 1680 description of new Charles Town at Oyster Point contains an important reference to the purchase of the town site. It seems likely, therefore, that he possessed first-hand knowledge of the transaction.

The English colonists probably paid the Etiwan with tools or practical goods rather than European coins made of silver and gold, which would have been rather useless to anyone living in the frontier wilderness of seventeenth-century Carolina. Before leaving London in 1669, the colonists had prepared for such transactions with the Indigenous population. The cargo accompanying the first settlers to South Carolina included significant quantities of glass beads, hatchets, knives, hoes, scissors, and textiles reserved specifically for “Indian trade.”[14] Like the Dutch settlers who purchased Manhattan using glass beads and other “trinkets,” the English in South Carolina bartered for Oyster Point using trade goods of practical use to the Native Americans. Recalling the words written by Maurice Mathews in 1680, we can surmise that the Etiwan accepted “a valuable consideration payed them . . . to remove them from their old habitations.”

The exact date of the payment to the Etiwan is lost, but it likely occurred at some point in the early weeks of 1672. The aforementioned agents responsible for selecting the town site might have negotiated with the resident Indians during the third week of January, but it seems unlikely that they also carried with them a sufficient quantity of trade goods to make an immediate purchase. One might argue that some unknown English settler or settlers might have paid the Etiwan to remove from Oyster Point sometime prior to March 1671, following Governor Sayle’'s order to preserve the lower part of that peninsula for future settlement. That scenario seems unlikely, however, owing to the value of the goods in question. The trade goods like hatchets, knives, and beads transported from London represented valuable assets in the frontier environment of early South Carolina. It seems unlikely that the colony’s nascent government would release such assets before officially confirming the purchase in question. The payment to the Etiwan, therefore, probably followed the Grand Council’s formal decision, made in mid-to-late January 1672, to create a town at Oyster Point.

Almost immediately after agents of South Carolina’s provincial government marked a tree at Oyster Point to designate the northern boundary of a future town, a number of men visited the peninsula and began staking claims to the forested land to the north of the reservation. John Coming, first mate of the frigate Carolina, joined with another of the first settlers, Henry Hughes, to claim a swath of land immediately north of the marked tree, stretching across the peninsula from the Ashley to the Cooper River. Later records demonstrate that the southern boundary of the Coming-Hughes tract was an imaginary line roughly commensurate with the center line of modern Beaufain Street, while its northern boundary was another imaginary line roughly commensurate with the center line of modern Calhoun Street. Similarly, Richard Cole claimed the swath of land to the north of John Coming and Henry Hughes, then Joseph Dalton to the north of Cole, then Hugh Carteret north of Dalton, above modern Grove Street, and so on in successive individual claims proceeding northward up the neck of the peninsula.[15]

The aforementioned 1787 plat of property surrounding Liberty Street in Charleston indicates that John Coming had purchased that land from the Etiwan Indians, but provides no further details. It seems likely, however, that Coming and his associate, Henry Hughes, bartered with the Etiwan in late January or perhaps early February 1672, immediately after the local government had identified the site of South Carolina’s future port town. On the 21st of February, 1672, John Coming and his wife, Affra, appeared with Henry Hughes before South Carolina’s Grand Council with a proposition. They volunteered to surrender one half of the land they had already claimed, immediately north of the marked tree at Oyster Point, “to be imployed in and towards enlarging of a towne and common of pasture there intended to be erected.”[16] This offer, which was later withdrawn, suggests that John Coming and his associates had bartered with the Etiwan sometime between mid-January and mid-February 1672 to secure their claim to the property in question. Whether or not their neighbors to the north made similar bargains is a question not answered by surviving records.

In late July 1672, five months after John Coming and friends appeared before the Grand Council, Governor John Yeamans ordered South Carolina’s Surveyor General, John Culpeper, “to admeasure and lay out for a Towne on the Oyster Poynt all that poynt of land there formerly allotted for the same [by Governor Sayle].” The precise acreage contained within the site was still unknown, so the governor directed Culpeper to include all of the land below “a marked tree formerly designed to direct the bounding line of the said town to the south.”[17]

The exact timing of the Etiwan exodus from Oyster Point is unknown, but it likely occurred during the six-month interval between Joseph Dalton’s glowing description of the site and Governor Yeamans’ order to lay out a grid of streets and building lots. In fact, the Etiwan removal from the peninsula might have delayed the government’s plan to proceed with the survey. On the same day that Governor Yeamans directed Mr. Culpeper to lay out the town, July 27th, 1672, the governor also ordered the surveyor to measure the adjoining tracts claimed by John Coming, Henry Hughes, Richard Cole, and so on, continuing northward up the peninsula. These men had staked their claims much earlier, but the interval of several months likely provided time for the Etiwan to dismantle their “old habitations” and the government to identify a new site “where they might plant and live confortablie.”

In the years after 1672, European settlers residing in the vicinity of modern Charleston described the Etiwan as residents of various lands east of the Cooper River. By 1676, the present Daniel Island was “commonly called Ittiwan Island.” Maurice Mathew’s 1680 description, cited earlier, mentions the presence of various “nighbour Indians” three miles west of the Cooper, along both sides of the Wando River. As the European population of South Carolina expanded in subsequent years, the Indigenous people were pushed farther away from the growing settlements around Charleston. The population of the Etiwan, like that of the other Indigenous tribes of coastal South Carolina, declined rapidly during the late seventeenth and early eighteen centuries. The Etiwan hold the distinction, however, of being the final band of the Lowcountry natives, mentioned for the last time in a legislative record of 1751.[18]

Conclusions:

Historians have long known, thanks to extant manuscripts, that at least nine other Indigenous tribes ceded their traditional homelands—all south of the Stono River—to the government of South Carolina between 1675 and 1684.[19] The earlier story of the Etiwan departure from the Charleston Peninsula, which likely occurred in the spring of 1672, has been largely forgotten, however. My goal in presenting this imprecise and incomplete reconstruction is to stimulate interest in the topic and perhaps inspire further research. Additional evidence of this Native American exodus might still exist in archives yet untapped, and future historians will hopefully refine the argument and chronology presented here.

The Etiwan Removal from Oyster Point paved the way for the creation of a port town between the rivers Ashley and Cooper that became new Charles Town in 1680. The modern City of Charleston celebrates the diverse layers of its colorful past, but the present narrative of its long history includes very little discussion of its Native American roots. In the future, perhaps we’ll hear residents and visitors recalling the Etiwan presence on Oyster Point. Perhaps, too, we’ll uncover further evidence of their distant lives beneath the landscape of twenty-first century Charleston.

[1] Samuel G. Stoney, ed., “A Contemporary view of Carolina in 1680,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 55 (July 1954): 154. The original source of this item is an undated manuscript “Coppie of a Letter from Charles Towne in Carolina,” located at Edinburgh University Library, Special Collections, Laing Collection, La. II, 718/1. In this quotation, and throughout this essay, I have reproduced the original spelling found in the manuscript source.

[2] Charleston County Register of Deeds Office, Plat Collection of John McCrady, plat No. 161. The property in question was granted to John Coming and Henry Hughes in the summer of 1672. Hughes sold his share of the grant to Coming in 1674, and Coming sold ninety acres (including the land around Liberty Street) to Isaac Mazyck sometime before October 1696. In November 1717, Mazyck sold to Bartholomew Gaillard ten acres bounded by the present King, Beaufain, St. Philip, and George Streets. The heirs of Gaillard sold the same ten acres to Joseph Wragg circa 1730, and the 1757 partition of Wragg’s estate awarded the same ten acres to Henrietta Wragg. Henrietta married William Wragg, and they jointly sold six acres to Patrick Hinds in August 1769. Sometime between August 1769 and April 1770, Hinds divided this six-acre parcel into thirty-two lots clustered around the newly-created Liberty and Wentworth Streets and began selling the lots to local investors, including Christopher Fitzsimons.

[3] For information about the choice to settle on Kiawah lands in 1670, Langdon Cheves, ed., “The Shaftesbury Papers and Other Records Relating to Carolina and the First Settlement on Ashley River Prior to the Year 1676,” in Collections of the South Carolina Historical Society, volume 5 (Charleston: South Carolina Historical Society, 1897), 165–174. This 1897 publication is also available online within the digitized collections of HathiTrust.

[4] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 322–23, 337; A. S. Salley Jr., ed., Journal of the Grand Council of South Carolina, August 25, 1671–June 24, 1680 (Columbia: The State Company, for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1907), 3.

[5] Charles H. Lesser and Ruth S. Green, South Carolina Begins: The Records of a Proprietary Colony, 1663–1721 (Columbia: South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1995), 124–25.

[6] See Lord Ashley’s letters to Sir John Yeamans, dated 10 April, 18 September, and 15 December 1671, in Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 342–44, 360–62; and the Lords Proprietors instructions to Captain Mathias Halsted, 1 May 1671, in Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 318–19.

[7] Governor Joseph West to Lord Ashley, 3 September 1671; Salley, Journal of the Grand Council, 3–5.

[8] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 339–40. The hand-drawn map or draught is now MPI 1/13 at the National Archives, Kew.

[9] Salley, Journal of the Grand Council, 5–6, 10.

[10] Salley, Journal of the Grand Council, 18–21, 27–28.

[11] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 374; this same text appears in Salley, Journal of the Grand Council, 24, with the word “in” rather than “on” before the word “Wandoe.”

[12] Joseph Dalton, at “Charlestown on Ashley River,” to Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper in London, dated 20 January 1671. The original manuscript letter, found among the Shaftesbury Papers in England, was later endorsed with the date 20 January 1672, which confirms Dalton’s use of the Julian Calendar (i.e., 20 January 1671/2). See Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 376–83.

[13] Gene Waddell, Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry, 1562–1751 (Columbia: Southern Studies Program, University of South Carolina, 1980), 6, 13, 199–212, 417.

[14] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 149–50.

[15] See the map and research presented in Henry A. M. Smith, “Charleston and Charleston Neck: The Original Grantees and the Settlements along the Ashley and Cooper Rivers,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 19 (January 1918): 7–16. See the map made by Henry A. M. Smith in 1918; see similar map on page 125 of Samuel Gaillard Stoney, This Is Charleston: A Survey of the Architectural Heritage of A Unique American City; second edition (Charleston, S.C.: Carolina Art Association, 1960). Note that Coming, Hughes, Cole, etc. apparently claimed and occupied the lands in question for some months before they received formal grants for the same from the provincial government in late July 1672.

[16] Salley, Journal of the Grand Council, 1671–1680, 29.

[17] A. S. Salley Jr., ed., Warrants for Lands in South Carolina, 1672–1679 (Columbia, S.C.: The State Co., for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1910), 22.

[18] Waddell, Indians, 212; Gene Waddell, “Ignorance and Deceit in Renaming Charleston’s Rivers: Some Observations about the Reliability of Historical Sources,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 89 (January 1988): 40–50; Michael K. Dahlman, Daniel Island (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2006).

[19] Waddell, Indians, 262, 304–7.

NEXT: The Grand Model: John Culpeper's 1672 Plan for Charles Town

PREVIOUSLY: Ghost Island: Desecration on the Ashley

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments