The Pirate Hunting Expeditions of 1718

Processing Request

Processing Request

This month marks the 300th anniversary of one of the dramatic episodes in the history of Charleston—the trial and execution of four dozen pirates who were captured off the Carolina coast in 1718. In today’s episode, we’ll explore the background preceding these extraordinary trials, and focus on the heroic efforts of South Carolina mariners to capture two of the most notorious pirate captains, Stede Bonnet and Richard Worley, and bring them to justice in Charleston. Even if you’re not a fan of pirate literature, you cannot deny that these events form a significant and swashbuckling chapter in the colorful history of the Carolina colony.

The War of Spanish Succession, known in the American colonies as Queen Anne’s War, raged from 1702 to 1713. Most of the action took place in Europe, and most of the military resources—including warships—remained on the other side of the Atlantic. Here in the American colonies, including those in the Caribbean Sea, the local governments of each of the warring nations issued licenses to private ships of war, or privateers, to attack their enemy’s shipping. In the poorly-regulated waters between the sparsely-populated colonies of North America and the West Indies, privateering was a fairly profitable business for more than a decade. At the conclusion of the war in 1713, however, all of those government-sanctioned privateers were suddenly out of business. Privateering was legal during a time of war, if you had a proper license, but that license expired on the declaration of peace. A number of the men engaged in this violent, sea-roving lifestyle continued unabated, however, and the government now looked on them as pirates; that is, as sea-faring thieves who illegally preyed on any vessel they found.

In the mid-1710s, the people living on the Atlantic coastline of North America and among the Caribbean islands witnessed a surge of piratical activity on the high seas. The colony of South Carolina was still small and thinly populated at that time, but the port of Charleston was growing in importance and wealth. Privateers and pirates had occasionally found shelter here since the beginning of the colony, and our local government made a minimal effort to check their abuses. The sea rovers frequently brought hard money and exotic goods to town, which induced many officials to refrain from investigating the legality of their supply chain. Most of the pirates operating at this time began converging on the islands of the Bahama Archipelago, which were then under the control of the same Lords Proprietors who owned the Carolina colonies. The Bahamas lacked a functioning government in the wake of Queen Anne’s War, however, so the Bahamas became a nurturing nest and gathering place for all manner of pirates. By the summer of 1716, the government of South Carolina was complaining to British officials that the “pirates of the Bahamas,” as they called them, had become a serious nuisance to Carolina shipping, and asked the British Navy to send reinforcements to check their activity.[1]

The British government heard complaints about pirates from their American colonies and from English merchants trying to ship goods to them. Rather than allocating expensive resources such as ships and sailors to combat the problem, the British government decided to follow a simpler and cheaper plan that had worked well in the past. On the 5th day of September, 1717, King George I issued a Royal Proclamation offering amnesty to pirates who would give up their criminal careers within the next twelve months. Pirates who confessed their crimes to the governor of any one of the British colonies, and took an oath promising good behavior, would be pardoned, and therefore exempt from prosecution. This time-limited offer did induce many pirates to seek protection, but it also drove many of the pirates out of their nest in the Bahama Islands, which temporarily lacked a functioning government, and into the waters of places like the Carolinas. In short, the king’s proclamation of September 1717 was the beginning of the end of the post-war pirate boom, but it made the situation temporarily worse for the people of Charleston.[2]

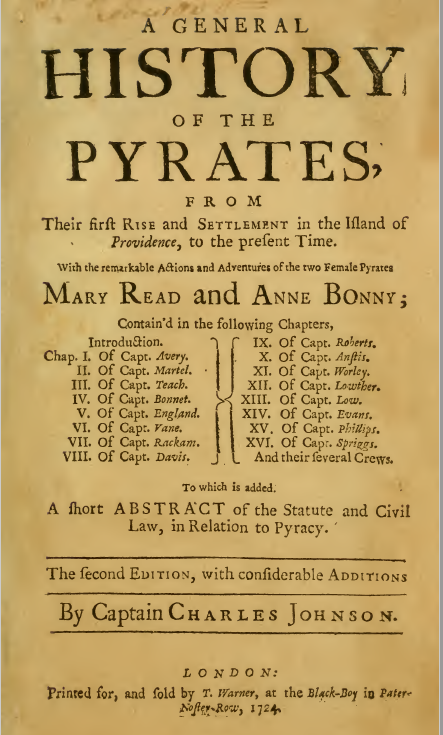

In the years 1717 and 1718, the people living along the coast of both North and South Carolina witnessed a surge in piratical activity. During this period, the vessels sailing into and out of the port of Charleston were frequently harassed by pirate vessels and even pirate squadrons led by men such as Major Stede Bonnet, Edward Teach or Thatch (alias Blackbeard), William Moody, Charles Vane, and Richard Worley. In early June of 1718, a powerful pirate squadron under Blackbeard’s command effectively closed the port of Charleston for a number of days by blockading the passage way in and out of the harbor. You can learn more about the biography and career of each of these men by reading the semi-fictional accounts published in the 1720s by one Captain Charles Johnson (whose true identity has been debated for nearly three centuries), under the title A General History of the Pyrates (especially the second, expanded edition of late 1724).

In the years 1717 and 1718, the people living along the coast of both North and South Carolina witnessed a surge in piratical activity. During this period, the vessels sailing into and out of the port of Charleston were frequently harassed by pirate vessels and even pirate squadrons led by men such as Major Stede Bonnet, Edward Teach or Thatch (alias Blackbeard), William Moody, Charles Vane, and Richard Worley. In early June of 1718, a powerful pirate squadron under Blackbeard’s command effectively closed the port of Charleston for a number of days by blockading the passage way in and out of the harbor. You can learn more about the biography and career of each of these men by reading the semi-fictional accounts published in the 1720s by one Captain Charles Johnson (whose true identity has been debated for nearly three centuries), under the title A General History of the Pyrates (especially the second, expanded edition of late 1724).

Pirate history has become a sort of industry of its own in recent years, and I generally try to avoid wading into those murky, semi-fictional waters. There is very little documentary evidence to support the lurid tales that are often published about the pirates and their activities, and I’m a stickler for bona fide evidence taken from primary sources—that is, accounts written or published by witnesses around the time of the events they describe. We are fortunate, therefore, that there is a fair amount of legitimate documentary evidence surrounding the most dramatic pirate episode in Charleston’s history—the capture, trial, and execution of four dozen pirates in the autumn of 1718. This episode is actually two separate stories that collided in November of that year, involving first the crew of Stede Bonnet’s pirate sloop, the Revenge, and second, the crew of Richard Worley’s pirate sloop, New York’s Revenge, and Worley's pirate ship called New York Revenge’s Revenge.

I’d like to share with you two brief narratives, written by unknown authors who lived in Charleston in the late 1710s. The first story details the capture of Major Stede Bonnet and his crew in October 1718, and the second concerns the capture of Richard Worley’s crew a few weeks later. I’ll save the details of the trials and executions for next week’s program. Let’s begin with a bit of background. In early 1718, Stede Bonnet and his crew had joined forces with the notorious Blackbeard and terrorized Charleston in June of that year. Afterwards, their pirate squadron went to North Carolina, where they disbanded and scuttled their main ship. Blackbeard and Bonnet parted ways, and separately both men took advantage of the King’s proclamation of 1717 by taking an oath promising to cease their pirate careers. Both men promptly reverted to their wicked ways, however, and each met his fate in a different manner shortly thereafter. Blackbeard’s final days belong to the history of North Carolina, but Stede Bonnet was brought to justice here in Charleston. The following account of Major Bonnet’s capture was published in London in 1719, as a preface to volume called The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet and Other Pirates. We’ll pick up the story right after Blackbeard and Bonnet parted ways in North Carolina:

We heard nothing of them till the beginning of September, 1718, when we had a particular information that a pirate sloop of ten guns and sixty men was at Cape Fear River, to the northward of this port, with two prizes, and had there begun to careen and refit. We did not doubt but we should then soon have another visit from them: To prevent which, Colonel William Rhett, of this province, waited on the governor [Robert Johnson], and generously offered himself to go with two sloops, and attack this pirate; which the governor agreed to, and accordingly [on September 4th] gave Colonel Rhett a commission and full power to fit such vessels as he thought proper for such a design.[3]

In a few days two sloops were equipped and manned: The Henry with eight guns and seventy men, commanded by Capt. John Masters, and the Sea-Nymph with eight guns and sixty men, commanded by Capt. Fayrer Hall, both under the entire direction and command of Colonel Rhett; who on the 10th of September went on board the Henry, and with the other sloop sailed from Charles-Town to Swillivants [Sullivan’s] Island, to put themselves in order for the cruize. And just then arrives a small ship from Antegoa [Antigua], one Cook master [that is, chief navigator], who gave us an account, that in sight of our bar he was taken and plunder’d by one Charles Vane a pirate, in a brigantine of twelve guns and ninety men, and who had also taken two other vessels bound in here; one a small sloop, Capt. Dill master, from Barbadoes; the other a brigantine [called the Dorothy], Capt. Thompson master, from Guinea, with ninety odd Negroes, which they took out of his vessels, and put on board another pirate sloop which they had under the command of one Yeates [Charles Yates], with fifteen men: which was fortunate to Capt. Thompson’s owners. Yeates having often attempted to leave this course of life, took this opportunity; for in the night he got away from the brigantine, and carried the sloop and Negroes into North Edisto River, to the southward of this port. The owners got their Negroes; and Yeates and his men had certificates [of pardon] given them from the government.[4]

Vane mean while continued cruizing off our bar, in hopes to catch Yeates: and it unfortunately happened that four ships, bound to London, and who had waited some time for a fair wind, got then over the bar, and two of them were taken; namely, the Neptune, a large pink with sixteen guns, Capt. King commander; and the Emperor, with ten guns, Capt. Power commander; but both very deep loaded.

Vane mean while continued cruizing off our bar, in hopes to catch Yeates: and it unfortunately happened that four ships, bound to London, and who had waited some time for a fair wind, got then over the bar, and two of them were taken; namely, the Neptune, a large pink with sixteen guns, Capt. King commander; and the Emperor, with ten guns, Capt. Power commander; but both very deep loaded.

The pirates gave out, while the prisoners were on board, that they design’d to go into some of our rivers to the southward, and there careen.

Colonel Rhett, upon hearing this, sailed over the bar the 15th of September, with the two sloops before mentioned; and having the wind northerly, went after the pirate Vane, and scour’d the rivers and inlets to the southward. But not meeting with him, tack’d and stood for Cape Fear River, in prosecution of his first design: And on the 26th [of September] following in the evening enter’d the mouth of the River, and saw over a point of land three sloops at anchor, which were the pirate and his two prizes; but it happen’d in going up the river the pilot ran both sloops a-ground, and it was dark before they were on float, which hinder’d their getting up that night. The pirate soon discover’d our sloops, and not knowing who they were, they manned three canoos, and sent them down the river, in order to view and take them, if they could; but they soon found that impracticable, our people lying on their arms all night, and kept a strict watch. The canoos return’d, and the pirates all that night made preparations for engaging; and the next morning, Saturday the 27th of September, they got under sail, and came down the river; and depending on the [Carolina] sloops sailing, [the pirates] designed only a running-fight. But our sloops stood for him, and got on his each quarter [that is, one sloop on each side of Bonnet’s stern], with design to board the pirate: which he finding, edged in towards the shore; and being warmly engaged, the sloop ran a-ground. Our sloops being in the same shoal water, were a-ground as soon as the pirate; the Henry, in which Col. Rhett was, grounded within pistol-shot of the pirate, and on his bow; the other sloop grounded right a-head of him, and almost out of gun-shot, which made him of little service to the colonel while they lay a-ground.

At this time the Pirates had a considerable advantage; for their sloop, after she was a-ground, listed from Colonel Rhett’s, by which means they were all covered; and the colonel’s sloop listing the same way, his men were much expos’d. Notwithstanding which, they kept a brisk fire the whole time they thus lay a-ground, which was near five hours. The pirates made a wiff in their bloody flag, and beckon’d with their hats in derision to our people to come on board them; which they only answered with chearful huzza’s, and told them it would soon be their turn. And which was so in a little time; for Colonel Rhett was first a-float, and got into deeper water; and after mending the sloop’s rigging, which, with the sloop, was much shatter’d in the engagement, they stood for the pirate, to give a finishing stroke, and designed to go directly on board him; which he prevented by sending a flag of truce [that is, they raised a white flag]: and after some time capitulating, they surrender’d themselves; and our people took possession of their sloop, and went up the river, in order to refit and water; where they retook the two prizes which the pirate had taken two months before. They were both sloops; one belonging to Antegoa [Antigua], Capt. Peter Manwareing commander; the other to Pensilvania [Pennsylvania], Capt. Thomas Reed commander.

Our people were well pleas’d to find this pirate to be Major Bonnet, who had so often infested our coast: He went then by the name of Capt. Thomas.

We had killed in the action on board the Henry ten men, and fourteen wounded; on board the Sea-Nymph two killed, and four wounded. The officers and mariners in both sloops behaved themselves with the greatest bravery; and had not the sloops so unluckily run a-ground, we should have taken the pirate with much less loss of men: But as he design’d to get by them, and so make a running-fight, our sloops were obliged to keep near him, to prevent his getting away. Of the pirates there were seven killed, and five wounded, two of which died soon after of their wounds.

Colonel Rhett weighed [anchor] the 30th of September from Cape Fear River, and arrived at Charles-Town the 3d of October, to the great joy of the whole province.

Bonnet and his crew two days after were put on shore; and there not being a publick prison, the pirates were kept at the Watch-House under a good guard of the militia: but Maj. Bonnet was committed into the custody of the Marshal [Nathaniel Partridge], at his House [on the south side of Tradd Street, between Church Street and East Bay].[5] And in a few days after David Herriot the master, and Ignatius Pell the boatswain, who were design’d to be evidence for the King against the other pirates, were removed from the rest of the crew to the said Marshal’s house, and every night two centinels set about the said house: But notwithstanding all that care, and the strict orders the governor often gave the marshal to take care of his prisoners, on the 24th of October Major Bonnet and Herriot made their escape, the boatswain refusing to go with them. When the account was brought [to] the governor that Bonnet had made his escape, he immediately issued out his proclamation, and promis’d a reward to any that would retake him; and accordingly sent several boats with armed men both to the northward and the southward in pursuit of them. But all return’d without being able to give any account of them.

Bonnet stood to the northward; but wanting necessaries, and the weather being bad, he was forc’d back, and so return’d with his canoo to Swillivants [Sullivan’s] Island, near Charles-Town, to fetch him supplies. But there being some information given to the governor, where it was thought they might find Bonnet, the governor sent for Colonel Rhett, and desired him to go in pursuit of Bonnet, and accordingly gave him a commission for that purpose. Whereupon the colonel, with proper craft, and some men, went away that night for Swillivants [Sullivan’s] Island. They searched very diligently for a long time before they found them; but at last discovering where they were, some of Colonel Rhett’s men fired at them, and killed the master Herriot upon the spot, and wounded one Negroe and an Indian. Bonnet submitted, and surrender’d himself; and the next morning, being November the 6th, was brought by Colonel Rhett to Charles-Town, and by the governor’s order was committed into safe custody, in order to his being brought to tryal.[6]

In his 1724 publication, A General History of the Pyrates, Captain Charles Johnson paraphrased much of the foregoing 1719 account of Stede Bonnet’s capture. Johnson’s volume also included a biographical sketch of Captain Richard Worley, but the author mistakenly set his inaccurate description of Worley’s final battle off the coast of Virginia. Shortly after the publication of Johnson’s 1724 History of the Pyrates, an unknown resident of Charleston sent the author in London a more accurate account of Worley’s last stand, which took place off the coast of South Carolina. Captain Johnson included this improved, contemporary description in a second volume of pirate history, which was published in 1728:

In his 1724 publication, A General History of the Pyrates, Captain Charles Johnson paraphrased much of the foregoing 1719 account of Stede Bonnet’s capture. Johnson’s volume also included a biographical sketch of Captain Richard Worley, but the author mistakenly set his inaccurate description of Worley’s final battle off the coast of Virginia. Shortly after the publication of Johnson’s 1724 History of the Pyrates, an unknown resident of Charleston sent the author in London a more accurate account of Worley’s last stand, which took place off the coast of South Carolina. Captain Johnson included this improved, contemporary description in a second volume of pirate history, which was published in 1728:

In October, 1718, Governor [Robert] Johnson was informed, that there was a pyrate ship off the bar of Charles Town, commanded by one [William] Moody, carrying 50 guns, and near 200 men, that he had taken two ships bound to that port from New England, and was come to an anchor with them to the southward of the bar; whereupon, he called his Council and the principal gentlemen of the place, and proposed to them, to fit out a proper force to go out and attack him, fearing he might lie there some time, as Thatch [Blackbeard] and [Charles] Vane had done before, and annoy the trade; which they unanimously agreeing, and there being, at that time, 14 or 15 ships in the harbour, he impress’d the Mediterranean Gally, Arthur Loan, and the King William, John Watkinson, commanders; and two sloops, one of which was the [sloop] Revenge, taken from Stede Bonnet, the pyrate, and another from Philadelphia; the former, Captain John Masters commanded, and the latter, Captain Fayrer Hall; which two captains had lately commanded the same sloops that took Bonnet at Cape Fear, about a month before. On board the Mediterranean was put 24 guns, and 30 on board the King William; the Revenge sloop had 8, and the other sloop 6 guns; and being thus equipp’d, the governor issued a proclamation, to encourage voluntiers to go on board, promising ’em all the booty to be shar’d among them, and that he himself would go in with ’em; but the ships and sloops before-mentioned being impress’d, it was natural for the commanders to desire some assurance of satisfaction to be made the owners, in case of a misfortune; so that the governor found it necessary to call the General Assembly of the province, without whom it was impossible for him to give them the satisfaction they desired, and who, without any hesitation, pass’d a vote, that they would pay for the said vessels, in case they were lost, according to an appraisement then made of them, and what other expences accrued to carry on this necessary expedition.[7] This way of proceeding took up a week’s time, during which, the governor ordered Scout Boats to ply up and down the river, as well to guard the port from any attempts the pyrates might make to land, as to hinder them from having advice of what was doing, and also laid an embargo on the shipping.

About three days before the governor sail’d, there appear’d off the barr a ship, and a sloop, who came to an anchor, and made a signal for a pilot; but they being suppos’d to be [the pirate William] Moody, and a sloop that had join’d him (as it was said he expected) no pilot was permitted to go near them, and thus they rid for four days, once or twice attempting to send their boat on shore, to an island, call’d, Suilivants Island (as they afterwards confess’d) to fetch water, of which they were in great want; but they were prevented by the Scout Boats before-mentioned: And, for want of which, they were obliged to continue in the same station, in hopes some ship would be coming in or going out, to relieve their necessities, they being very short also of provisions.

And now all things being ready, and about three hundred men on board the four vessels, the governor thought himself a match for Moody in his 50 gun ship, although he should be, as they thought he was, join’d by a sloop: And therefore, he sail’d with his fleet below Johnson’s Fort over night, and the next morning by break of day, weigh’d anchor, and by eight in the morning, they were over the bar.

The pyrate sloop immediately slipt her cable, hoisted a black flag, and stood to get between the bar and the governor’s ships, to prevent their going in again, as they expected they would have done; and in a small time after, the pyrate ship also hoisted a black flag, and made sail after the sloop; during all this time, the men on board the governor’s vessels did not appear, nor was there any shew of guns, until they came within half gun-shot; when the governor hoisted a flag at the main-top-mast head of the Mediterranean, they all flung out their guns, and giving them their broad-sides, the pyrates immediately run, whereupon, the governor ordered the two sloops after the pyrate sloop, who stood in towards the shore, while himself and the King William followed the ship who stood the contrary way to Sea. She seemed to have many [gun] ports, and very full of men, tho’ she had fir’d but from two guns, which occasion’d no small wonder on board the governor, why she had not flung open her ports, and made use of more guns, she being imagined all this while to be Moody.

The sloop, which proved to be [Richard] Worley, was attacked by the two sloops so warmly, that the men run into the hold, all except Worley himself and some few others, who were killed on the deck; and being boarded, they took her within sight of Charles Town: The people seeing the action from the tops of their houses, and the masts of the ships in the harbour, where they had placed themselves for that purpose; but it was three in the afternoon before the governor and the King William came up with the ship, who, during the chase, had taken down her [black] flagg, and wrapping the small arms in it, had thrown them over-board; and also flung over her boat and what other things they thought would lighten her, but all would not do: The King William came first up with her, and firing his chase guns, killed several of the people on board, and they immediately struck [this is, surrendered]; when, to the no small surprize of the Governor and his company, there appeared near as many women on board as men, who were not a few neither. The ship proving to be the Eagle, bound from London to Virginia, with convicts; but had been taken by Worley off the Cape of Virginia, and had upwards of 100 men and 30 women on board. Many of the men had taken on with the pyrates, and as such, found in Carolina the fate they had deserved at home, being hang’d at Charles Town; the virtuous ladies were designed to have been landed on one of the uninhabited Bahama Islands, where there was a proper port for these rovers to put in, at any time, to refresh themselves, after the fatigue of the sea. And thus a most hopeful colony would have commenced, if they had had but provisions and water sufficient to have carried them to sea; but their fate kept them so long before the port of Charles Town, until they were destroyed, and an end put to their wicked lives, in the manner before-mentioned.[8]

In our next episode of the Charleston Time Machine, we’ll focus on the trials of Stede Bonnet and his crew, as well as the trial of the remnants of Richard Worley’s crew, in the South Carolina Court of Vice Admiralty, in late October and November of 1718. After several days of dramatic, eye-witness testimony, most of which was published in 1719, a total of forty-nine men were hanged for piracy at White Point. Tune in next week to learn who was condemned, who was acquitted, and who turned state’s evidence against his pirate brethren. And, of course, we’ll consider where in Charleston the bones of those 49 pirates might rest today.

[1] On 1 August 1716, the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly resolved to ask Capt. Thomas Howard, commander of the HMS Shoreham, then in Charleston, to remain on our coast to defend us against the “pirates of the Bahamas.” See the manuscript South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Journal of the S.C. Commons House of Assembly (Green’s copy), 1716–21, page 154.

[2] See Cecil Headlam, ed., Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series. America and West Indies, August 1717–Dec. 1718 (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1930), 252–53 (item No. 536).

[3] Rhett’s commission from Gov. Johnson is found in SCDAH, Records of the Secretary of the Province, 1709–1721, page 93. A transcription of this material appears in the W.PA. transcripts at CCPL, volume 57, page 87.

[4] Charles Yates, William Finsely, Thomas Winbourn, John Bush, John Mounsey, Francis Carter, Peter Legront, David Stephens, and Henry Hamilton received pardon from Governor Robert Johnson in Charleston on 10 September 1718. SCDAH, Records of the Secretary of the Province, 1709–1721, pages 67–68. A transcription of this material appears in the W.PA. transcripts at CCPL, volume 57, page 63.

[5] The marshal is identified in Shirley Carter Hughson, The Carolina Pirates and Colonial Commerce, 1670–1740 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1894), 101, and in the manuscript records of the South Carolina Court of Vice Admiralty, 1716–1718, at SCDAH. In his 1722 will, Captain Nathaniel Partridge devised to his son his residence located on an eastern portion of town lot No. 73, which forms the southeast corner of Tradd and Church Streets. See his will, dated 28 April 1722 and recorded on 4 April 1723, in Will Book 1722–24 at SCDAH, or in the W.P.A. transcripts at CCPL, volume 1 (Will Book 1722–23), pages 34–36.

[6] Anonymous, The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and other Pirates . . . To which is Prefix’d, An Account of the Taking of the said Major Bonnet, and the rest of the Pirates (London: Benj. Cowse, 1719), iii–vi.

[7] The South Carolina legislative journals for the years 1718 and 1719 do not survive, so there is no extant documentary evidence of the government’s actions during this time besides descriptions sent by local writers to correspondents elsewhere.

[8] Charles Johnson, The History of the Pyrates, Containing the Lives of Captain Misson, Captain Bowen, Captain Kidd, Captain Tew, Captain Halsey, Captain White, Captain Condent, Captain Bellamy, Captain Fly, Captain Howard, Captain Lewis, Captain Cornelius, Captain Williams, Captain Burgess, Captain North, and Their Several Crews. . . Vol. II (London: T. Woodward, [1728]), 324–29. You can read this volume online at https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/17002.

PREVIOUS: The Tail of Washington’s Horse

NEXT: The Charleston Pirate Trials of 1718

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments