Phebe Fletcher: A ‘Magdalene’ in Revolutionary Charleston

Processing Request

Processing Request

Phebe Fletcher was an intriguing woman of eighteenth-century Charleston whose unconventional lifestyle earned both derision and respect from her neighbors. Born to a respectable family of unknown origin, she was “seduced” from the bounds of traditional feminine “virtue” and thereafter obliged to associate with “vicious” persons, Black and White, to forge an independent career in a patriarchal society. She acquired a colorful reputation as a woman of dubious morals, but Charlestonians long remembered the benevolent care she rendered to ailing soldiers during the American Revolution.

Based on this brief outline of her life, we might conclude that Phebe Fletcher would make an excellent character for a historical novel or screen play. Unfortunately, very little information about her survives to illuminate much of her colorful and perhaps brief existence. I’ve scoured various South Carolina archives in recent years for scraps of documentary evidence of her life and times, but she will likely remain an obscure and enigmatic figure. Considering the many thousands of women residing in early South Carolina who left no documentary traces of their lives, however, we are fortunate to know anything at all about her life. As a sort of tribute to those legions of forgotten women, we can at least attempt to reconstruct a modest biography of Phebe Fletcher.[1]

Our pool of biographical evidence consists of just a handful of documents: nearly a dozen brief newspaper notices published between 1785 and 1791; one receipt for furniture sold in 1788; one census record from 1790; and one paragraph from a book published sixty years after Phebe’s death. The most important of these resources is the memoir published in 1851 by Dr. Joseph Johnson, titled Traditions and Reminiscences Chiefly of the American Revolution in the South. As I mentioned in a pair of episodes about Charleston’s Liberty Tree, this nineteenth-century author was the son of a blacksmith named William Johnson who was a well-connected veteran of the American Revolution in South Carolina. The younger Johnson, born in 1776, might have known Phebe Fletcher during his youth in Charleston, and evidently heard about her war-time activities from his patriotic father. Whatever their relationship, Miss Fletcher’s actions during the war made a sufficient impression on the Johnson family to sustain her memory across the decades.

Joseph Johnson’s 1851 monograph includes a paragraph of around three hundred words summarizing Phebe’s life story. The text contains unique information that cannot be verified or refuted at the present time, but it nonetheless represents a useful outline of her biography. Rather than simply presenting Johnson’s description in one large block, I’d like to dissect his text into smaller bits and combine them with other source materials, annotations, and contextual clues to create a more robust narrative.

There were several people bearing the surname “Fletcher” in the Lowcountry of eighteenth-century South Carolina, but at the moment there is not a sufficient pool of genealogical data to connect Phebe to any particular branch or family unit. Nothing definitive can be said about her age or place of birth, though I suspect she was born around or perhaps just before the middle of the eighteenth century. In his 1851 monograph, Joseph Johnson stated that Phebe “had received a decent, virtuous education,” words implying that she came from a respectable family of some means. This Fletcher clan, if that was indeed her original surname, either resided in South Carolina at the time of Phebe’s birth or migrated to the colony some time prior to the American Revolution.

After introducing his subject, Dr. Johnson’s narrative takes an immediate digression into scandalous territory. At some unspecified point in Phebe’s youth, probably as a young lady of marriageable age, Johnson recalled that she “had been seduced from the paths of rectitude, by a young man of fashion.” That is to say, she engaged in some act of premarital sex—consensual or otherwise—during an era when God-fearing Protestants within the British realm condemned such activity as an unforgivable trespass of social propriety. Johnson identified the young man in question simply as “a native of Charleston,” who evidently harbored no intention of continuing their physical relationship within the traditional legal union of husband and wife. On the contrary, the rakish lad bragged about his intimacy with Miss Fletcher and thereby destroyed her reputation as a respectable, marriageable woman. By gaining intimate knowledge of Phebe’s body and, according to Joseph Johnson, “by boasting of his success,” this Charleston blackguard “doubly blasted her prospects in life.” No urbane, class-conscious gentleman of that time and place would have considered marrying a woman who had been used in such a fashion, and the conservative social mores of that era offered few opportunities for unmarried women of Phebe’s social class to pursue respectable, independent careers. “Being shunned by the virtuous,” surmised Dr. Johnson, “she had no choice; she could only associate with the vicious.”[2]

Here we encounter what I consider the central mystery of Phebe Fletcher’s biography: She was evidently ostracized from polite society, but to what extent? How far down the ladder of social hierarchy did she fall? At least one modern historian of Revolutionary-era Charleston has described Phebe Fletcher as a prostitute, but I believe she was a more complex character than that base term implies.[3] In fairness to her memory and those of countless other forgotten women in similar circumstances, let’s consider the context of Johnson’s text and clues from the later years of Phebe’s life.

Dr. Johnson clearly viewed Phebe Fletcher as a sympathetic but tragically-flawed character, but we must acknowledge that he was not a neutral reporter. He was a man of his times—a conservative, affluent, white, Protestant, amateur historian embedded within a rigidly paternalistic society that condoned and defended the practice of chattel slavery and human trafficking. As such, we can detect elements of personal bias in his text. His 1851 memoir, for example, uses the most politely-cryptic language to inform the reader that Phebe “had no choice,” after her public humiliation, but to associate with persons whom Johnson characterized as “vicious.” But who, in Johnson’s eye, were the “vicious” people of late eighteenth-century Charleston—working-class people lacking social polish? Anyone who rejected the conservative social mores of the day? Persons of African and Native American ancestry? Or perhaps all of the above?

Rather than embarking on a career as a prostitute after her fall from grace, Phebe might simply have abandoned the exclusive social sphere of the affluent white minority that dominated South Carolina at the time. I think it is significant that Joseph Johnson prefaced his brief bio of Miss Fletcher by describing her as “a Magdalene in Charleston.” Although some modern readers might consider the term “Magdalene” a synonym for prostitute, writers of centuries past more commonly used the word to describe a reformed prostitute, or, more generally, a benevolent woman with a dishonorable past. In either case, Johnson’s text casts Phebe Fletcher as a victim, an object of sympathy, but she might simply have been an independent woman whose agency and independence offended her dour neighbors.

Joseph Johnson revived the memory of Phebe Fletcher in 1851 as a sidelight to the sprawling and complex struggle for American Independence. More precisely, he couched her brief biography within a discussion of the harsh treatment of American soldiers after the British Army captured the former capital of South Carolina in May 1780. “There was a Magdalene in Charleston, at that time,” wrote Johnson, “who merited much consideration from the Americans, for her devoted attendance on the sick soldiers, and her many acts of benevolence to those who were most in need.”[4] Because the author was just four years old when British forces commenced their oppressive occupation of the capital, he likely learned of Phebe’s memorable acts from older eye-witnesses in the post-war years. Among the most likely sources was Dr. Johnson’s own father and his brothers-in-arms, who might have personally received comfort from the young Magdalene.

William Johnson (1741–1818), father of Joseph, served as a private in the Charleston Battalion of Artillery and participated in the gallant defense of the town’s tabby Horn Work during the British siege of April and May 1780. Three months after the town surrendered and British authorities paroled the enlisted American soldiers, Johnson was among dozens of men arrested and confined aboard a British prison ship in Charleston Harbor. One week later, he and others were transported to St. Augustine, Florida. After being transferred to Philadelphia in late July 1781, Private Johnson and his comrades returned to Charleston at the conclusion of the war in early 1783.[5]

In his youth during the post-war years, Joseph Johnson evidently heard stories from his father and perhaps other veterans in the community who recalled Phebe Fletcher’s benevolence during the war. Notably, Johnson stated that she merited praise from the Americans, not the British forces who occupied the city for more than two and a half years. We might imagine, therefore, that Phebe attended men wounded during the bloody siege of 1780 and then comforted those confined within the several prison ships anchored in the harbor throughout the long occupation. What contact or commerce she had British soldiers, officers, and loyalists in Charleston during the early 1780s is currently unknown, but might possibly be discovered with further research.

I have not yet found any reference to Phebe Fletcher among the sparse extant records of life in Charleston during the years immediately after the British evacuation of December 1782. In the autumn of 1785, however, a local newspaper published a notice related to an undocumented series of curious cultural events. An advertisement in the Charleston Evening Gazette invited the community to “an elegant ball” to take place on the evening of October 10th at what was then called No. 12 Pinckney Street (a building now long gone). The soirée was described as being “for the benefit of Miss Phœbe Fletcher,” but this was no a charity event. Rather, it was probably the conclusion of a subscription series of entertainments for which she played the role of both hostess and performer. As commonly seen in theatrical and concert series of that era, the “benefit” in question was a sort of gratuitous reward for Phebe’s hospitality and/or management of the series.[6]

One week later, the editors of the Evening Gazette published an audacious review of Phebe Fletcher’s “elegant ball” in Pinckney Street, under the heading “Al Fresco Intelligence.” The remarkable text contains exotic and romantic details that echo the contemporary European fascination with the Near East, alluding to an Ottoman or Turkish harem in the same manner as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s 1782 opera, The Abduction from the Seraglio. Peppered with libidinous double entendres, the text depicts a hedonistic soirée hosted by a talented woman well-known to her inebriated guests:

“On Monday se’ennight [that is, seven nights ago] a subscription ball, for the benefit of Miss Phebe Fletcher was given at her apartments in Pinckney street. The saloon and drawing-room were ornamented with festoons of myrtles and gold leaf, and elegantly variegated with tasty interspersion of natural and artificial flowers; a handsome display of embossed and fashionable plate, the dazzling beauties of the ladies in their newest charms and dresses; numerous wax tapers well placed, and luxuriantly reflecting the gay scene in rich mirrors, gave an air of enchantment to the whole, and carried imagination to the paradise of Mahomet, where all true believers are promised twenty-seven wives a piece.

An Ethiopian band [that is, a band of Black musicians] lulled the soul to peace, and soft delight, whilst the fair hostess handed about several kinds of rich wines, and when any body drank [to] her health, she curtseyed in a most becoming manner, looking at the same time so prim as if butter would not melt in her mouth. The hacknied, vulgar custom of supper gave way to the more modern one of tea,—to which, by way of relish, was added cold tongues, oisters, hams, salt herrings, ornamented with little sprigs of parsley. The ladies could not swallow a morsel, but the gentlemen were not so nice; they threw down large mouthfuls, diluting their food with bumbers of generous wine, until at last some of them were of opinion that the room was running round and round. A song being called, as soon as silence could be procured, a young lady attempted ‘Love’s the greatest bliss below’ [a song from George Frideric Handel’s 1745 masque Comus], but having a monstrous cold, did not give so much satisfaction as could be wished, however Miss Phebe made amends, by singing several songs as clear as a bell. The ladies now began to tuck up their gowns, and get every thing in order for dancing; the most select and admired cotillions, rigadoons, and country dances were performed with tolerable exactness, some of the nymphs were a little at a loss in crossing over, but then they were as easy as could be when they figured in. Two young ladies went through an Allemande, in the Asiatick taste; their contortions, animated gestures, and sympathetic manner, tended to rouse in the spectators certain ideas. About four o’clock the ladies retired, and the gentlemen followed hard after.”[7]

Phebe Fletcher must have hosted a number of similar events in Charleston during the 1780s that received far less public attention. Gossip about such decadent soirées apparently spread across the city, inspiring scorn from conservative neighbors and admiration from others. In his 1851 memoir, Joseph Johnson related the story of a young lady, probably a curious teenager, who aspired to join Phebe’s merry entourage. Johnson included this brief vignette to illustrate what he perceived as Miss Fletcher’s contrite nature. “Many acts of her life,” he wrote, “showed that she was fully sensible of her degraded state, and wished to make amends, if possible.” We may never know the identity of the girl in question, but the brief story proves Johnson’s point:

“A giddy, thoughtless young lady left the home of her respectable parents, and repaired to that of Phebe Fletcher, saying that she wished to live with her. Phebe invited her into a room, and locked the door on her, that she might not be exposed; then went off to the parents of the young lady, told them what she had done, and added that she knew too well the evils resulting from a loss of reputation and of virtuous society, to countenance its sacrifice by any one. The parents of the young lady took her home, not only treated her frailty with lenity, but with increased parental attentions. She not only repented and reformed, but became the exemplary mother of a respectable family. The secret never was whispered. I never heard the name of the family, few ever heard of the incident, and when mentioned, it was only to give credit to the kind Magdalene.”[8]

In mid-August 1786, “Miss Fletcher” advertised in local newspapers “to inform the gentlemen of both city and country, that she has, for their accommodation, taken a large, pleasant and commodious new house, No. 16, Meeting-street, at present called CITY-HOTEL, where she assures such gentlemen as may favor her with their company, that they will at all times have the best liquors and attendance the city can afford, with tea, coffee, beef steaks, &c. by a professed cook, and relishes at all times.”[9] Owing to the repeated renumbering of Charleston street addresses in centuries past, it would be extremely difficult, but not necessarily impossible, to identify the present location of Phebe’s “City Hotel” or of her other residences. Subsequent public notices published in 1787 demonstrate that she held a one-year license from the City Council of Charleston to retail “spiritous liquors” and to keep a billiard table at her Meeting Street premises, but they also inform us that she had not renewed her liquor license at the end of the year.[10] Unable or unwilling to purchase a fixed abode for her business and residence, Phebe rented rooms and was apparently obliged to move house from time to time.

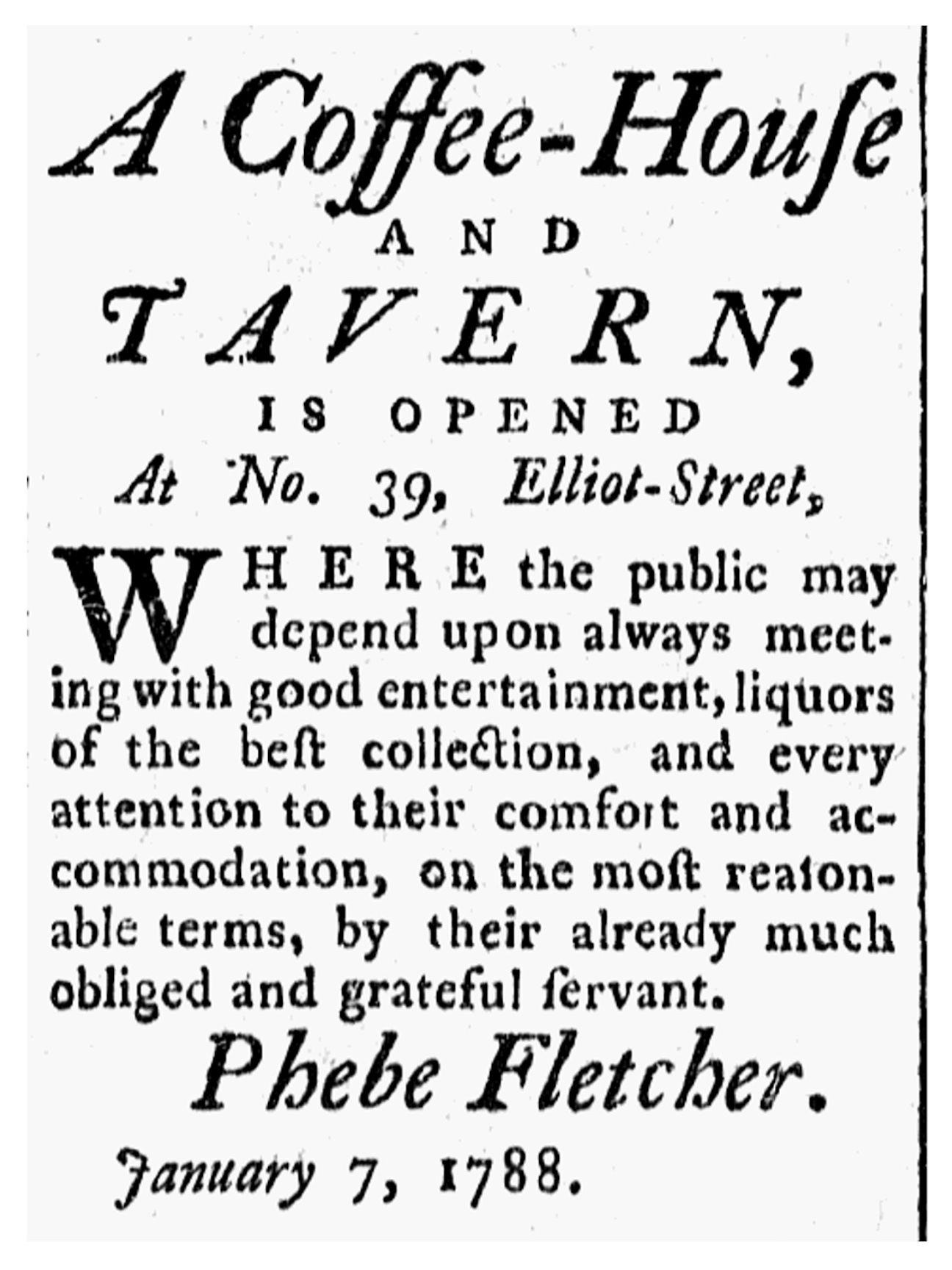

In January 1788, Phebe Fletcher advertised that she had opened a “Coffee-House and Tavern” at a site then identified as No. 39 Elliott Street, “where the public may depend upon always meeting with good entertainment, liquors of the best collection, and every attention to their comfort and accommodation, on the most reasonable terms.”[11] Three months later, however, she sold a significant quantity of “household goods” to an obscure mariner named John Magnall. Whether this transaction represented the liquidation of Phebe’s business, or the division of property with a departing partner, is now unknown. At any rate, the surviving bill-of-sale provides a valuable snapshot of her private chambers. For £30 sterling, Fletcher sold (with the original spelling) “one featherbed two mattrasses, one bedstead, one lott [of] fifteen windsor chairs three blankets three deal tables, one Dutch table three mahagony tables seven pictures one commode, one looking glass one trunk of cloaths nine boxes one bar ten iron potts two stew pans, two dozen plates one dozen knives & forks, four tubs one cooler one pail two pair of iron dogs, ten tumblers two decanters two fish dishes one sett of Chaina one dozen of wine glasses three window curtains four candlesticks and a pair of silver sugar tongs and five silver tea spoons.”[12]

Nine weeks later, some unknown intruder or perhaps an invited guest robbed Phebe’s residence on the evening of 1 July 1788, taking “3 silver tea spoons, feather edged,” one of which bore the hallmark of Charleston silversmith William Wightman, “and is marked P. F.,” while “the others are Philadelphia made spoons.” She offered a “handsome reward” for the return of the spoons, which might or might not have formed part of the property sold earlier to John Magnall.[13]

According to the published Charleston Directory of 1790, Phebe Fletcher’s next residence was at No. 5 Beresford Street (now Fulton Street), in the center of what was then a racially diverse, working-class neighborhood called Dutch Town.[14] That same year, the first Federal census of the United States recorded her presence at an unspecified address in the urban Charleston parishes of St. Philip and St. Michael. Miss Fletcher was identified as the head of a household that included just two “free white females” of unspecified ages.[15] The identity of her housemate is entirely unknown. We might imagine that this mystery woman could have been a servant, a protégé, or perhaps even Phebe’s domestic partner. Considering this last-mentioned possibility, one might revisit Joseph Johnson’s narrative with a fresh perspective. Perhaps the root of Phebe’s nonconformity was not necessarily humiliation, but a rejection of men and the patriarchal framework that abridged her freedom of expression. Rather than a delicate victim, she might have been an assertive woman who craved an independent life beyond the constraints of eighteenth-century propriety. Instead of a pious Magdalene, perhaps she had more in common with the twentieth-century fictional bonne-vivante Auntie Mame.

The final piece of evidence relating to Phebe’s life appeared during Charleston’s first post-war horse-racing season in early March 1791. Through the local newspapers, she announced that she had taken charge of “Booth No. 6” at a newly-created venue called Washington Race Course (now Hampton Park), where she offered “for the entertainment of the gentlemen in general and her old friends in particular, the best liquors of every kind, together with the best provisions prepared after the most elegant manner, and in this way humbly solicits the attention of the public.”[16]

Phebe’s attendance at the inauguration of Washington Race Course proved to be her final public campaign. Whether she was in declining health, or fit as a fiddle at that time is now unknown, but her life ended some days later. According a very brief notice published in a Charleston newspaper, Phebe Fletcher died on 26 March 1791.[17] Curiously, a Philadelphia magazine published a brief mention of her death a few weeks later—a fact suggesting that she might have had friends or family in the City of Brotherly Love.[18] The cause of death is lost to history, so we can only speculate about the events leading to her demise. Her name does not appear among the extant registers of churches in urban Charleston, though she might have been buried in the countryside, or perhaps was interred in the city’s public cemetery on the west side of the peninsula (see Episode No. 200). Similarly, I can find no last will and testament for Phebe Fletcher, and no inventory of her estate, suggesting that either she had no possessions worth mentioning, or perhaps that the local government chose to ignore the tangible relicts of a woman living beyond the pale of polite society. At least some of her neighbors paid their respects at Phebe’s graveside. “Such was the general respect for her goodness of heart,” recalled Joseph Johnson in 1851, “that many of the most respectable inhabitants attended her funeral.”[19]

Phebe Fletcher was an independent, unconventional woman living on the fringes of the gentrified society of late eighteenth-century Charleston. Although some in that community might have sneered at her exuberant lifestyle and the company she kept, others remembered the acts of kindness she displayed during the darkest days of the Revolution. We owe much of our knowledge of Phebe Fletcher to the antebellum prose of Joseph Johnson, who also provided a fitting benediction to conclude this brief biography: “Peace to her memory. May he, who can best judge of the frailties of our nature, cast the mantle of pardon over her sins, and reward her good deeds.”[20]

[1] Some extant documents spell Fletcher’s first name with the Latin ligature “œ” (“Phœbe”), but I have elected to render the name “Phebe” in this essay for the ease of modern readers.

[2] Joseph Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences Chiefly of the American Revolution in the South (Charleston, S.C.: Walker and James, 1851), 313.

[3] Carl P. Borick, Relieve Us of This Burthen: American Prisoners of War in the Revolutionary South, 1780–1782 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2012), page 22, described Phebe Fletcher as “a Charleston prostitute,” citing, in footnote 56, Joseph Johnson’s Traditions and Reminiscences, page 313.

[4] Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences, 313.

[5] Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences, 210, 211, 254, 316; South Carolina and American General Gazette, 6 September 1780, page 3; Mabel L. Webber, ed., “Josiah Smith’s Diary, 1780–1781,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 34 (January 1933): 31–33; Alexander S. Salley, Jr., ed., Stub Entries to Indents Issued In Payment of Claims against South Carolina Growing out of the Revolution, Books U-W (Columbia: The State Company, for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1918), 213. For a general overview of the siege, see Carl P. Borick, A Gallant Defense: The Siege of Charleston, 1780 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2003).

[6] Charleston Evening Gazette, 7 October 1785, page 3.

[7] Charleston Evening Gazette, 20 October 1785, page 2.

[8] Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences, 313–14.

[9] Charleston Morning Post, 15 August 1786, page 1.

[10] Charleston Morning Post, 25 April 1787, page 3, “City Treasurer’s Office”; Charleston Morning Post, 5 July 1787, page 3, “City Treasurer’s Office”; City Gazette [Charleston, S.C.], 7 November 1787, page 3.

[11] City Gazette, 7 January 1788, page 1.

[12] Phœbe Fletcher to John Magnall, bill of sale, 28 April 1788, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Miscellaneous Records (Main Series), volume QQ: 625.

[13] City Gazette, 3 July 1788, page 3. William Wightman was a Charleston silversmith.

[14] Jacob Milligan, ed., The Charleston Directory; and Revenue System of the United States (Charleston, S.C.: T. B. Bowen, 1790).

[15] See page 20 of the 1790 manuscript census of the urban parishes of St. Philip and St. Michael, Charleston District, South Carolina, accessible on microfilm in CCPL’s South Carolina History Room, and through the online databases hosted by Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org.

[16] City Gazette, 1 March 1791, page 3.

[17] City Gazette, 28 March 1791 (Monday), page 3, “Died.) On Saturday last [i.e., 26 March 1791], Mrs. [sic] Phebe Fletcher.”

[18] The American Museum, or Universal Magazine [Philadelphia, Pa.], volume 9 (April 1791), Appendix 3, page 32, “Died. . . . South Carolina. In Charleston. . . . Mrs. [sic] Phebe Fletcher.”

[19] Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences, 314.

[20] Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences, 314.

NEXT: Cash and Credit in South Carolina before the U.S. Dollar

PREVIOUSLY: Thomas Francis Meagher, Irish Patriot, in Charleston

See more from Charleston Time Machine