Parishes, Districts, and Counties in Early South Carolina

Processing Request

Processing Request

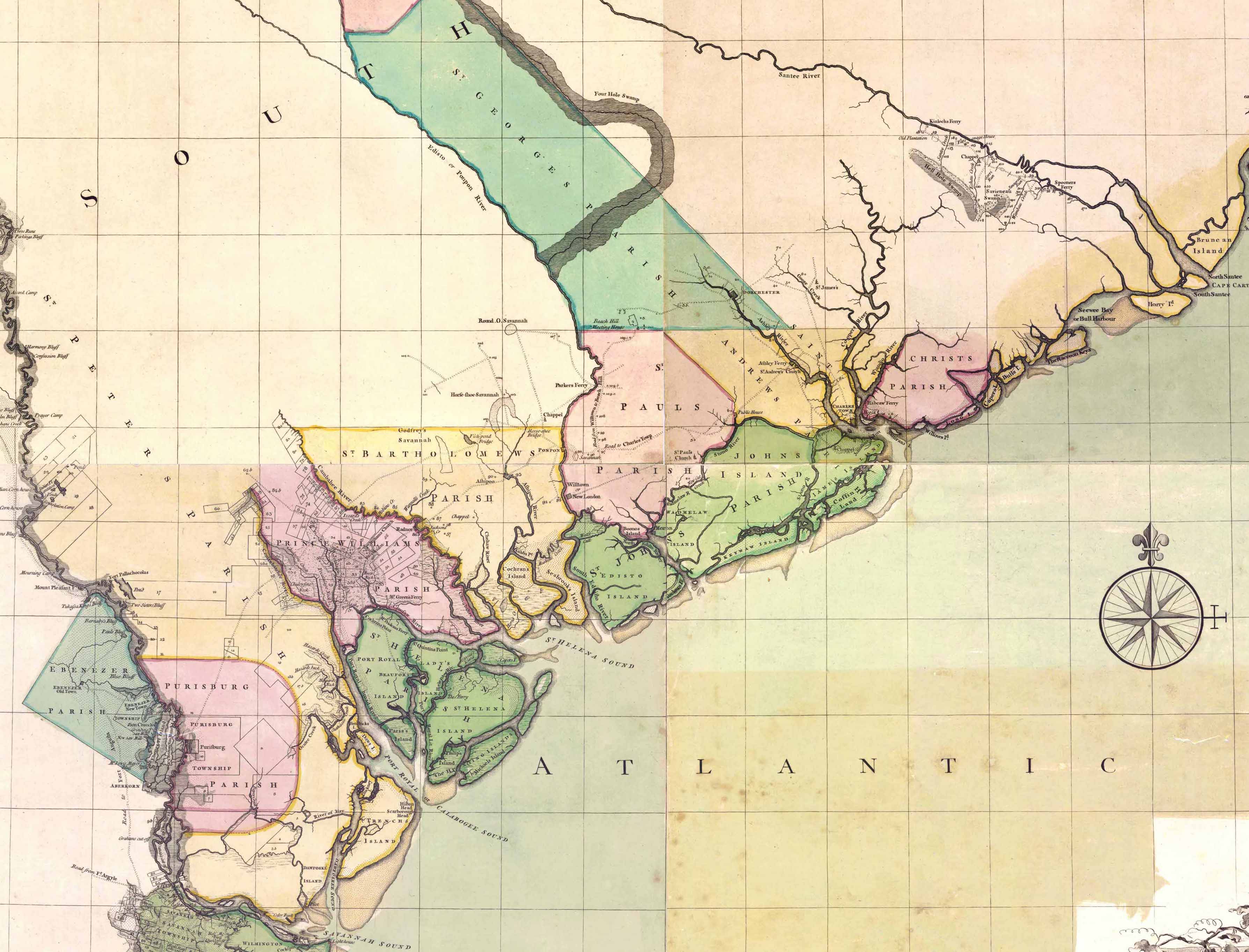

Scattered across coastal South Carolina, one finds a variety of saints’ names applied to numerous landmarks, institutions, and roads. Think, for example, of St. John’s High School on John’s Island, St. Andrew’s Boulevard west of the Ashley River, St. Paul’s Fire Department in the town of Ravenel, and St. George, the seat of Dorchester County, just to name a few. Such names lack historical context within our modern, secular landscape, but they represent vestiges of a long-forgotten patchwork of ecclesiastical parishes that once defined the political geography of lower South Carolina.

Through a series of statutes ratified between 1706 and 1778, the South Carolina legislature created twenty-four parishes that encompassed all of the land between the Savannah River and the North Carolina border, from the Atlantic Ocean westward nearly a hundred miles inland. We now have counties instead of parishes in the Palmetto State, but the two systems of administrative jurisdiction co-existed on the landscape of lower South Carolina until the autumn of 1865. If you’re curious about the state’s geopolitical evolution, or if you’re trying to trace your Lowcountry ancestors in the generations before the Civil War, it’s imperative to have at least a passing familiarity with the old parishes that were created more than three centuries ago.[1]

The earliest political divisions within the boundaries of modern South Carolina commenced in 1682, when the Lords Proprietors, who owned all of Carolina, authorized the creation of three counties within the southwestern part of the colony. Colleton County included all of the land between the Combahee River and the Stono River; Berkeley County originally included everything between the Stono River and Awendaw Creek, but was later expanded northward; Craven County originally included all of the land from Awendaw Creek to the Santee River, but was later shifted northward to encompass the land between the Santee River and the province of North Carolina. A fourth county was created in 1684 to embrace the land between the Savannah and Combahee Rivers, and was variously called Carteret County, Port Royal County, and finally, by 1708, Granville County.

Like their modern equivalents, each of the four original counties was intended to have its own courts for the proceedings of civil, criminal, and probate law. Because most of South Carolina’s early population settled between the Stono and Santee Rivers, however, the courts of Berkeley County, located within urban Charleston, served the population of the entire colony for nearly a century. Despite this judicial monopoly in the colonial capital, each of the four original counties continued to play an important political role. For more than twenty years after their creation in the 1680s, Granville, Colleton, Berkeley, and Craven Counties served as tax districts and as election districts for choosing representatives to sit in the lower house of South Carolina’s bicameral provincial assembly.

Like their modern equivalents, each of the four original counties was intended to have its own courts for the proceedings of civil, criminal, and probate law. Because most of South Carolina’s early population settled between the Stono and Santee Rivers, however, the courts of Berkeley County, located within urban Charleston, served the population of the entire colony for nearly a century. Despite this judicial monopoly in the colonial capital, each of the four original counties continued to play an important political role. For more than twenty years after their creation in the 1680s, Granville, Colleton, Berkeley, and Craven Counties served as tax districts and as election districts for choosing representatives to sit in the lower house of South Carolina’s bicameral provincial assembly.

The boundaries of South Carolina’s four early counties have been obscured by a succession of political changes. Although two of the original names—Berkeley and Colleton—have survived, the present county boundaries of South Carolina bear no relationship to those created in the 1680s. This geopolitical evolution commenced in the early days of the eighteenth century, during the administration of Governor Sir Nathaniel Johnson. As an ardent supporter of the Protestant Church of England, Governor Johnson sought to establish his preferred form of worship as the official religion of South Carolina. To accomplish this partisan goal, the provincial General Assembly ratified a controversial law in 1704 that divided the most populous county—Berkeley—into seven Anglican parishes to be supported by the public treasury. Following a chorus of complaints from the non-Anglican citizens of South Carolina, who formed the majority of the population, the Lords Proprietors of Carolina disallowed or canceled the offending statute. The provincial legislature ratified a less discriminatory version of the same material in late 1706, which received official approval in England the following year.[2]

The “Church Act” of 1706, as it was commonly called, created ten parishes across the South Carolina Lowcountry—seven within Berkeley County, two in Colleton County, and one for all of Craven County. Within each of these parishes, the provincial legislature applied public tax revenue for the construction and maintenance of an Anglican church and a smaller “chapel of ease,” and to pay the salary of an Anglican minister. Because the act of 1706 provided only meager descriptions of the boundaries of the original ten parishes, a subsequent act ratified in 1708 provided more robust geographic details. (See the footnotes below for links to historic resources that provide greater detail).

Proceeding north to south, South Carolina’s original parishes included St. James, on the Santee River; Christ Church, in the area now called Mount Pleasant; St. Thomas and St. Dennis (later spelled "Denis") were initially separate parishes, but were soon collapsed into a single entity that encompassed Daniel Island and the mainland between the Wando and Cooper Rivers; St. John, Berkeley, was situated on the northwestern reaches of the Cooper River; St. James, in the area surrounding Goose Creek; St. Philip, encompassing the neck of land between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers; St. Andrew, between the Ashley and Stono Rivers; St. Paul, between the Stono and the South Edisto Rivers; and St. Bartholomew, between the South Edisto and Combahee Rivers.[3]

Over the next seventy-odd years, the South Carolina legislature created fifteen additional parishes. A legislative act of June 1712 created the Parish of St. Helena in Granville County, embracing all of the land between the Combahee and Savannah Rivers.[4] Another act in December 1717 separated the northern part of St. Andrew’s Parish into a new division called St. George. Because it was centered around the old settlement at the town of Dorchester, it soon became known as the Parish of St. George, Dorchester.[5] In March of 1721/2, the northern part of St. James, Santee, became the Parish of Prince George, called Prince George, Winyah, around the settlement that became Georgetown.[6]

Besides authorizing the creation of several Anglican parishes, the Church Act of 1706 did not challenge the geographic divisions of South Carolina’s political landscape. The new parishes were merely subdivisions of the colony’s four original counties, and citizens continued to hold county-wide elections to select representatives in the provincial legislature. That tradition changed in the autumn of 1716, however, when the South Carolina General Assembly ratified a law that designated the various parishes as the geographic districts for both civic elections and tax collection. The Lords Proprietors revoked this change in the summer of 1718, but, following the Revolution of 1719, the provincial legislature re-enacted the parochial law in September 1721. That same month, the South Carolina General Assembly adopted another law to erect courts and courthouses in each of the four counties, but this plan never matured. For a further half-century, the courts of Berkeley County, located within urban Charleston, continued to function as the sole venue for all civil, probate, and criminal process in South Carolina.[7]

Besides authorizing the creation of several Anglican parishes, the Church Act of 1706 did not challenge the geographic divisions of South Carolina’s political landscape. The new parishes were merely subdivisions of the colony’s four original counties, and citizens continued to hold county-wide elections to select representatives in the provincial legislature. That tradition changed in the autumn of 1716, however, when the South Carolina General Assembly ratified a law that designated the various parishes as the geographic districts for both civic elections and tax collection. The Lords Proprietors revoked this change in the summer of 1718, but, following the Revolution of 1719, the provincial legislature re-enacted the parochial law in September 1721. That same month, the South Carolina General Assembly adopted another law to erect courts and courthouses in each of the four counties, but this plan never matured. For a further half-century, the courts of Berkeley County, located within urban Charleston, continued to function as the sole venue for all civil, probate, and criminal process in South Carolina.[7]

As the colony’s rural population increased during the second quarter of the eighteenth century, the inhabitants gained representation in the lower or “Commons House” of South Carolina’s General Assembly through the creation of additional parishes. The government’s plan to attract settlers by creating several townships on the western frontier—a scheme advocated by Governor Robert Johnson in the early 1730s—anticipated that each of the new townships would eventually grow large enough to form a distinct parish. This plan was only partially successful, as demonstrated by the list of new parishes created in the ensuing decades.[8]

For example, a single legislative act in April 1734 created two further parishes. The eastern part of St. Paul’s Parish, including John’s Island, Edisto, Wadmalaw, Seabrook, Kiawah, and other sea islands between the Stono and South Edisto Rivers, became the Parish of St. John, Colleton. At the same time, the western part of Prince George, Winyah, became the Parish of Prince Frederick.[9] The northwestern part of St. Helena’s Parish, between the Coosaw River and the Combahee River, became a separate parish in May 1745, called Prince William.[10] The area around the township of Purrysburgh on the north side of the Savannah River became the Parish of St. Peter in February 1746/7.[11]

The central Parish of St. Philip on Charleston Neck was divided in June 1751, at which time everything south of the centerline of Broad Street became the Parish of St. Michael.[12] The old parish of St. James, Santee, was further trimmed in May 1754, when an act of the legislature separated its western half into the Parish of St. Stephen.[13] Similarly, the western half of Prince Frederick Parish was separated in May 1757 to become the Parish of St. Mark.[14] Another legislative act in May 1767 created two new parishes. The southwestern part of St. Helena’s Parish, between the previous subdivisions called St. Peter and Prince William, became the Parish of St. Luke, while the eastern part of Prince George, Winyah, became the coastal Parish of All Saints.[15] Two separate acts both ratified in April 1768 created the Parish of St. Matthew on the western edge of Berkeley County, and the Parish of St. David on the western frontier of Craven County.[16]

The appeal of creating new parishes waned in South Carolina during the second half of the eighteenth century. While parishes served as convenient local jurisdictions for ecclesiastical, electoral, and tax purposes, they offered no other legal or judicial services to their constituents. After numerous citizens on the northwestern frontier complained about the necessity of travelling to distant Charleston to file a suit or attend a trial, the provincial government finally responded. In April 1768, the South Carolina legislature abolished the four counties created in the 1680s and divided the province into seven “precincts” or “districts,” each with its own judicial seat, at Charleston, Beaufort, Orangeburg, Georgetown, Camden, Cheraw, and Ninety-Six. The British Government rejected and cancelled this 1768 act, but approved the revised version that was ratified in Charleston in July 1769. Following the construction of several new courthouses, South Carolina’s first circuit-court system became functional in 1772, and citizens were no longer obliged to visit Charleston to settle most of their legal affairs. This significant administrative change did not affect the status of the old parishes, however, which continued to serve as election and tax districts across the Lowcountry.[17]

The appeal of creating new parishes waned in South Carolina during the second half of the eighteenth century. While parishes served as convenient local jurisdictions for ecclesiastical, electoral, and tax purposes, they offered no other legal or judicial services to their constituents. After numerous citizens on the northwestern frontier complained about the necessity of travelling to distant Charleston to file a suit or attend a trial, the provincial government finally responded. In April 1768, the South Carolina legislature abolished the four counties created in the 1680s and divided the province into seven “precincts” or “districts,” each with its own judicial seat, at Charleston, Beaufort, Orangeburg, Georgetown, Camden, Cheraw, and Ninety-Six. The British Government rejected and cancelled this 1768 act, but approved the revised version that was ratified in Charleston in July 1769. Following the construction of several new courthouses, South Carolina’s first circuit-court system became functional in 1772, and citizens were no longer obliged to visit Charleston to settle most of their legal affairs. This significant administrative change did not affect the status of the old parishes, however, which continued to serve as election and tax districts across the Lowcountry.[17]

South Carolina declared its independence from Great Britain in March of 1776 by adopting a temporary constitution that maintained the provincial government’s existing framework. The final parish of lower South Carolina was created on March 16th, 1778 when the legislature separated a portion of St. Mark’s Parish, surrounding the township of Orangeburg, into a new entity called Orange Parish.[18] Three days later, the state General Assembly adopted a revised constitution that dis-established the Church of England and thus ended the long-established practice of using public funds to support and maintain the state’s Anglican churches. Despite this ecclesiastical change, the twenty-four parishes continued to function as election and tax districts within the oldest settled portions of the state.[19]

In the aftermath of the American Revolution, the elected leaders of South Carolina sought to refine the structure of local government to accommodate the needs of a growing population. The state General Assembly appointed a number of commissioners in the spring of 1783 to begin dividing each of South Carolina’s seven circuit court districts (created in 1768–69) into several counties. This work was completed by the spring of 1785, at which time the legislature formally divided the Palmetto State into thirty-four counties organized within seven regional districts. As with the judicial reorganization of 1769, this post-war change required the construction of many new courthouses across South Carolina, but the boundaries of the colonial parishes remained intact.[20] The revised state constitution of 1790 confirmed this tradition.[21]

Popular reluctance to embrace the county system of 1785 undermined its success, and the state’s elected leaders sowed further resentment by creating several additional counties while abolishing and merging others. After a decade of complaints from constituents, the South Carolina legislature adopted a plan in 1798 to replace the state’s seven judicial districts and thirty-odd counties with a simpler system of twenty-four districts that bore many of the same names as the counties they replaced. This change, which went into effect on January 1st, 1800, again disrupted the geography of South Carolina’s courthouses and judicial circuits, but the old parishes continued to function as election precincts within the new Lowcountry districts.[22]

The parish divisions of lower South Carolina continued to thrive during the first half of the nineteenth century, many with their colonial-era churches still intact, while the state legislature occasionally revised the new-fangled judicial districts to accommodate the expanding population. Both of these systems of civil jurisdiction disappeared in the aftermath of the Civil War, however, as a wave of new ideas supplanted old traditions. The revised state constitution of 1865, for example, replaced both the colonial-era parishes and the antebellum districts with a uniform system of election districts. This post-bellum measure was superseded three years later by the creation of South Carolina’s modern counties in the progressive state constitution of 1868. Although subsequent constitutional revisions altered their number and names, the present county system of South Carolina is rooted in the post-war efforts to reconstruct and modernize the state government.[23]

The parish divisions of lower South Carolina continued to thrive during the first half of the nineteenth century, many with their colonial-era churches still intact, while the state legislature occasionally revised the new-fangled judicial districts to accommodate the expanding population. Both of these systems of civil jurisdiction disappeared in the aftermath of the Civil War, however, as a wave of new ideas supplanted old traditions. The revised state constitution of 1865, for example, replaced both the colonial-era parishes and the antebellum districts with a uniform system of election districts. This post-bellum measure was superseded three years later by the creation of South Carolina’s modern counties in the progressive state constitution of 1868. Although subsequent constitutional revisions altered their number and names, the present county system of South Carolina is rooted in the post-war efforts to reconstruct and modernize the state government.[23]

Memories of the old parish divisions lingered for several generations beyond the Reconstruction Era and into the twentieth century. The twin parishes of St. Philip and St. Michael, for example, continued to exist as an election precinct within greater Charleston County for many years until the expanding suburban population overshadowed their significance. Local residents and visitors can still find the names of the colonial-era parishes scattered across the Lowcountry in the names of streets, business, and parks, but few recognize the deep legacy invoked by these modern entities. Beyond a handful of old churches and slow-moving rivers, there is no tangible fabric to illuminate the physical context of the old parishes. By learning about their geographic boundaries and complex history, however, we can use our imaginations to revisit the landscape of early South Carolina.

[1] For a brief ecclesiastical history of each parish, see Frederick Dalcho, An Historical Account of the Protestant Episcopal Church in South-Carolina (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1820).

[2] Act No. 225, “An Act for the establishment of Religious Worship in this Province according to the Church of England, and for the erecting of Churches for the public Worship of God, and also for the maintenance of Ministers, and the building convenient Houses for them,” ratified on 4 November 1704, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 2 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1837), 236–46; Act No. 256, “An Act for the Establishment of Religious Worship in this Province, according to the Church of England, and for the erecting of Churches for the Public Worship of God, and also for the Maintenance of Ministers and the building [of] convenient Houses for them,” ratified on 30 November 1706, Cooper, Statutes at Large, 2: 282–94. For a discussion of the context surrounding the Church Acts of 1704 and 1706, see M. Eugene Sirmans, Colonial South Carolina: A Political History, 1663–1763 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966); Robert M. Weir, Colonial South Carolina: A History (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997). For a discussion of religious discrimination in early South Carolina, see Episode No. 142, “The Myth of the Holy City.”

[3] Act No. 280, “An Additional Act to an Act entituled [sic] An Act for the establishment of religious worship in this Province according to the Church of England, and for the erecting of Churches for the public worship of God, and also for the maintenance of Ministers and the building [of] convenient houses for them,” ratified on 18 December 1708, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 2: 328–30.

[4] See section XIII of Act No. 307, “An Additional Act to the several Acts relating to the Establishment of Religious Worship in this Province, and now in force in the same, and also to the Act for securing the Provincial Library at Charles Town in Carolina,” ratified on 7 June 1712, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 2: 366–76.

[5] See Act No. 381, “An Act to Erect the Upper Part of the Parish of St. Andrew’s on the Ashley River, into a Distinct Parish Separate from the Lower Part of the said Parish,” ratified on 11 December 1717; and Act No. 444, “An Act to alter the bounds of St. George’s Parish,” ratified on 15 September 1721, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 3 (Columbia: A. S. Johnston, 1838), 9–11, 134.

[6] Act No. 458, “An Act for erecting the settlement at Winyaw, in Craven County, into a distinct Parish from St. James Santee, in the said County,” ratified on 10 March 1721/2, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 3: 171–72. Many publications assert that the parish of Prince George, Winyah, was created on 10 March 1721, but that date reflects the contemporary use of the Julian Calendar. The correct date is 10 March 1721/2. The act in question was signed by Governor Francis Nicholson, who arrived in South Carolina in late May 1721.

[7] Act No. 365, “An Act to keep inviolate and preserve the freedom of Elections, and appoint who shall be deemed and adjudged capable of choosing or being chosen Members of the Commons House of Assembly, ratified on 15 December 1716, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 2: 683–91; Act No. 446, “An Act to ascertain the manner and form of electing members to represent the inhabitants of this Province in the Commons House of Assembly, and to appoint who shall be deemed and adjudged capable of choosing or being chosen members of the said House,” ratified on 15 September 1721, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 3: 135–40; Act No. 473, “An Act for establishing County and Precinct Courts,” ratified on 20 September 1721, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 166–76.

[8] For more information about the township scheme, see Robert L. Meriwether, The Expansion of South Carolina, 1729–1765 (Kingsport, Tenn.: Southern Publishers, 1940).

[9] Act No. 567, “An Act for dividing the Parishes of St. Paul’s, in Colleton County, and Prince George Winyaw, in Craven County,” ratified on 9 April 1734, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 3: 374–76. The boundaries of Prince Frederick were refined by Act No. 587, “An Act to appoint Commissioners to lay out and mend Roads and appoint Ferries for the Parishes of Prince George Winyaw and Prince Frederick; and to explain part of an act entitled ‘An Act for dividing the Parishes of St. Paul, in Colleton County, and Prince George Winyaw, in Craven County,’ and to appoint a ferry over Santee River,” ratified on 29 March 1735, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 9 (Columbia: A. S. Johnston, 1841), 87–88.

[10] Act No. 731, “An Act to divide St. Helen’s [sic] Parish, and to erect a separate and distinct Parish in Granville County, by the name of Prince William, and to ascertain the bound thereof,” ratified on 25 May 1745, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 3: 658–60.

[11] Act No. 736, “An Act for erecting the township of Purrysburgh and parts adjacent, into a separate and distinct Parish,” ratified on 17 February 1746/7, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 3: 668–69.

[12] Act No. 795, “An Act for dividing the Parish of St. Philip, Charlestown, and for establishing another parish in the said town, by the name of the Parish of St. Michael; and for appointing Commissioners for the building of a Church and a Parsonage House in the said Parish; and appointing one member more to represent the inhabitants of the said town in the General Assembly of this Province; and for ascertaining the number of members to represent the inhabitants of the said Parishes, respectively, in the said assembly; and providing an addition to the salary of the present rector of the Parish of St. Philip, during his incumbency,” ratified on 14 June 1751, in McCord, Statutes at Large, 7: 79–84.

[13] Act No. 824, “An Act to divide the Parish of St. James Santee, in Craven County, and for establishing another Parish in the said County, by the name of the Parish of St. Stephen, and appointing the Chapel of Ease in the said Parish of St. Stephen to be the Parish Church, and declaring the Chapel of Ease and Echaw, in the Parish of St. James Santee, to be the Parish Church, and for appointing Commissioners to erect a Chapel of Ease near Wambaw Bridge, in the said Parish of St. James Santee, and for ascertaining the number of Members to represent the inhabitants of the said Parishes respectively in the General Assembly of this Province, and for appointing Commissioners for the High Roads in the said Parishes respectively,” ratified on 11 May 1754, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 4 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnson, 1838), 8–10.

[14] Act No. 858, “An Act dividing the Parish of Prince Frederick, in Craven County, and Establishing another Parish in the said County by the name of the Parish of St. Mark, and appointing Commissioners for building a Church and Parsonage House therein, and ascertaining the number of Members to represent the inhabitants of the said Parishes respectively in the General Assembly of this Province,” in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 4: 35–37.

[15] Act No. 961, “An Act for establishing a Parish in Granville County, by the name of St. Luke, and also for establishing a Parish in Craven County by the name of All Saints; and for erecting a Chapel of Ease in the Parish of Prince Frederick,” ratified on 23 May 1767, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 4: 266–68. The British Government disallowed this 1767 act on 9 December 1770; see Lieutenant Governor William Bull’s proclamation of 15 February 1771 in South Carolina Gazette, 28 February 1771, page 1. Nevertheless, the inhabitants of South Carolina seem to have ignored the dis-establishment of both parishes. All Saints was officially re-created, however, by Act No 1071, “An Act for establishing a Parish in Craven County, by the name of All Saints,” ratified on 16 March 1778, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 4: 407–8.

[16] Act No. 971, “An Act for establishing a Parish in Berkley [sic] County, by the name of St. Matthew, and for declaring the Road therein mentioned to be a Public Road,” ratified on 12 April 1768, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 4: 298–300.

[17] See section 1 of Act No. 980, “An Act for establishing Courts, Building Gaols, and Appointing Sheriffs and other Officers, for the more convenient administration of justice in this province,” ratified on 12 April 1768, in McCord, Statutes at Large, 7: 197–205; “An Act for establishing Courts, Building Goals [jails], and Appointing Sheriffs and other Officers, for the more convenient Administration of Justice in this Province,” ratified on 29 July 1769, in John Faucheraud Grimke, ed., The Public Laws of the State of South-Carolina (Philadelphia: R. Aitken, 1790), 268–73.

[18] Act No. 1072, “An Act for dividing the township of Orangeburgh from the Parish of St. Matthew, into a separate Parish, by the name of Orange Parish, and for the other purposes therein mentioned,” ratified on 16 March 1778, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 4: 408–9.

[19] See the South Carolina Constitution of 1776, and Articles 12 and 38 of the Constitution of 1778 in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 1 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1836), 128–34, 137–46.

[20] Act No. 1263, “An Act for laying off the several Counties therein mentioned, and appointing Commissioners to erect the public buildings,” ratified on 12 March 1785, in Cooper, Statutes at Large of South Carolina, 4: 661–66; Act No. 1281, “An Act for establishing County Courts, and for regulating the proceedings therein,” ratified on 17 or 24 March 1785, in McCord, Statutes at Large, 7: 211–42.

[21] See Article 1, Section 3, of the Constitution of 1790 in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 1: 184–93.

[22] Act No. 1706, “An Act to establish an uniform and more convenient System of Judicature, ratified on 21 December 1798, in McCord, Statutes at Large, 7: 283–89.

[23] See Article I, Section 3, of the South Carolina Constitution of 1865, and Article II, Section 2 of the South Carolina Constitution of 1868.

NEXT: Charleston’s Daily Bread: Regulating Retail Loaves from 1750 to 1858

PREVIOUSLY: Passenger Trains between Charleston and Summerville, from the Best Friend to BRT

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments