Pandemic and Panic: Influenza in 1918 Charleston

Processing Request

Processing Request

Pandemic and panic visited Charleston in the autumn of 1918 when the Spanish Influenza spread throughout the community in a wave of acute sickness and death. Under the shadow of the Great War raging in Europe, the city was ill-equipped to counter a major health crisis. Many healthcare professionals and supplies had been sent overseas, leaving limited resources available at home. Quarantine, isolation, and volunteer efforts soon arrested the disease, however, and Charleston rebounded from its first modern epidemic with a lamentable but limited death toll.

This is a story about the City of Charleston, the boundaries of which in 1918 were confined to the peninsula of land between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, extending from White Point Garden on the south to Mount Pleasant Street on the north. All of the surrounding areas, including all points north of the city, east of the Cooper, west of the Ashley, and the neighboring sea islands, were sparsely populated, unincorporated rural areas within Charleston County. The influenza of 1918 affected such rural areas to a degree, but the relative isolation of country life provided a good measure of protection to folks living outside the densely-populated city.

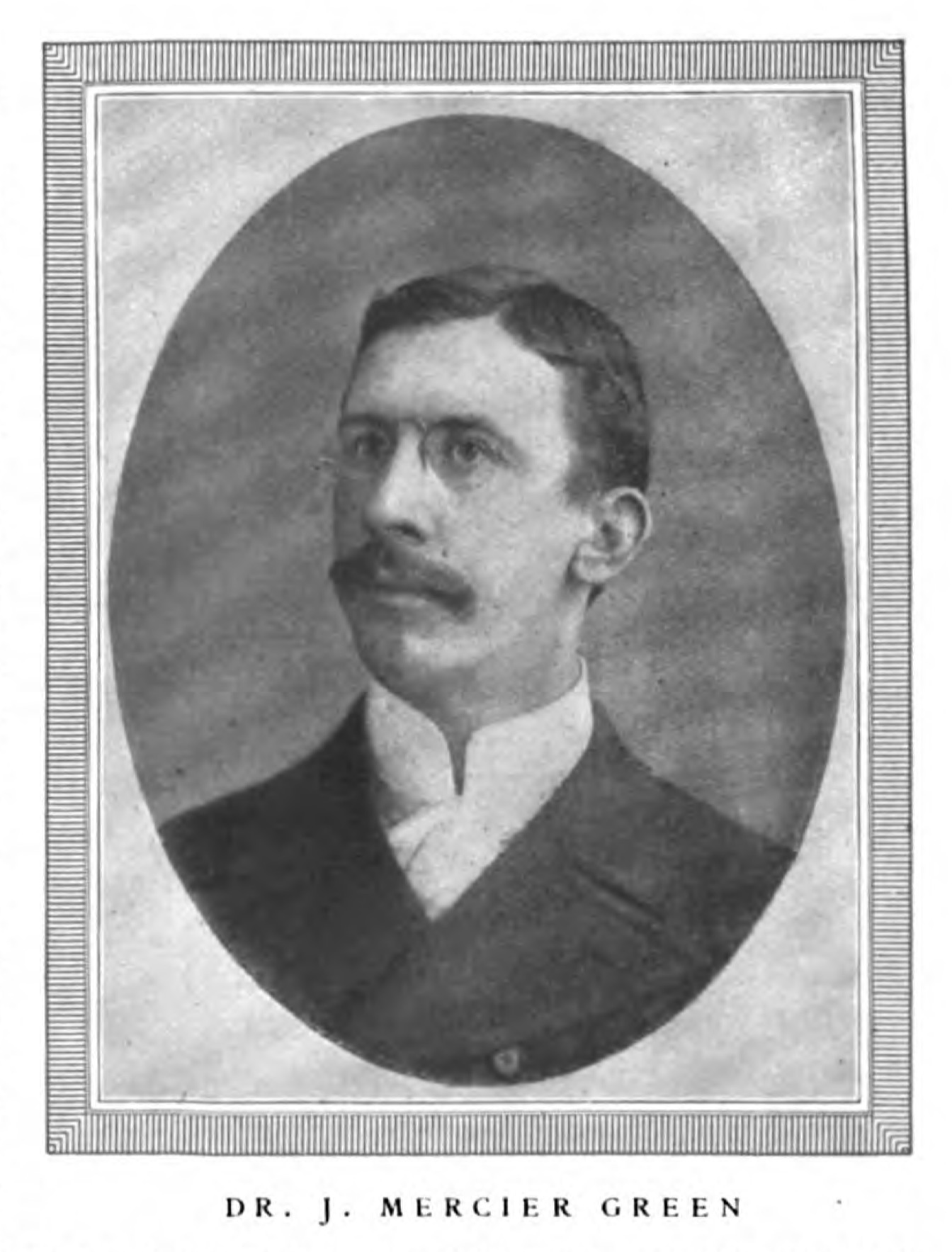

In 1918, the City of Charleston was home to just over 61,000 people, of whom approximately 50.5% were African-American. Owing to the mobilization of military personnel during the war, the city’s population had temporarily increased to approximately 85,000 people.[1] To safeguard the health of these inhabitants, the city had created a municipal Board of Health in the early years of the nineteenth century. In the autumn of 1918, Dr. John Mercier Green, M.D. (1869–1931) served as Charleston’s chief Health Officer and directed a small staff of trained professionals. There was no county-level heath office at that time, so Dr. Green interacted directly with the state-level Board of Health, headed by Dr. James Hayne. Dr. Hayne in turn liaised with a Federal body created in 1912 and still around today, called the United States Public Health Service.

In 1918, the City of Charleston was home to just over 61,000 people, of whom approximately 50.5% were African-American. Owing to the mobilization of military personnel during the war, the city’s population had temporarily increased to approximately 85,000 people.[1] To safeguard the health of these inhabitants, the city had created a municipal Board of Health in the early years of the nineteenth century. In the autumn of 1918, Dr. John Mercier Green, M.D. (1869–1931) served as Charleston’s chief Health Officer and directed a small staff of trained professionals. There was no county-level heath office at that time, so Dr. Green interacted directly with the state-level Board of Health, headed by Dr. James Hayne. Dr. Hayne in turn liaised with a Federal body created in 1912 and still around today, called the United States Public Health Service.

The influenza pandemic of 1918 brought death and suffering to Charleston, but it was not the city’s first experience with the disease. The United States first experienced a mass outbreak of influenza in 1889, but the virus did not reach Charleston that year. A subsequent outbreak in 1890 did include Charleston, however, and “la grippe” (as it was then called) claimed thirty-six lives in the city. Influenza spread across the United States again in 1891, and the local toll was a further forty-four lives. From that time forward, less virulent strains of influenza returned to Charleston each autumn, claiming at least a few deaths annually during the early years of the twentieth century.[2]

In April of 1917, the United States officially entered the “Great War” then raging across Europe. A powerful strain of influenza affected troops fighting on the continent in 1917, spreading rapidly through crowded barracks and soldiers moving rapidly across borders in congested ships and trains. Said to have originated or first appeared in Spain, the so-called “Spanish Influenza” raged across Europe, claiming many lives, and then dissipated before it became a problem in the United States. The mass movement of American soldiers across the Atlantic Ocean in 1917 and 1918 expedited the spread of various diseases, and the Spanish flu soon appeared in domestic military bases. By the late summer of 1918, it had reached epidemic proportions in the United States. That fall it spread from northern ports southward along the Atlantic seaboard, following the lines of vehicular and maritime transportation down to Charleston and beyond.

The first report of the so-called Spanish Influenza in Charleston County occurred at the Naval Training Camp, a war-time adjunct to the Charleston Naval Base located on the banks of the Cooper River in what is now the city of North Charleston. Physicians at the training camp identified the notorious disease among the young recruits on Monday, September 16th. The following day, naval officials issued an order prohibiting the “bluejackets,” as the cadets were known, from leaving the facility.[3] By Thursday, September 19th, the quarantined training camp reported 350 cases of influenza, although Navy officials were quick to assert that “the disease seems to be well under control.”[4]

The hope of containing the foreign virus at the Naval Training Camp to the north of Charleston was doomed by the close interaction between the armed forces and the campus of the South Carolina Military Academy, known as The Citadel, on Marion Square in the heart of the city. Not surprisingly, the first cases of “Spanish” influenza in urban Charleston were reported among the Citadel cadets. In an effort to check the further spread of the deadly disease, the school announced an immediate suspension of all classes and activities on the evening of Sunday, September 29th.[5]

The following day, September 30th, the resident United States Health Officer in South Carolina, Dr. French Simpson, held a press conference in Columbia. Having just returned from Washington, D.C. with fresh instructions, Dr. Simpson advised citizens to take action to preserve their good health. “The public had just as well prepare themselves for a spread of the disease if they did not take every precautionary measure possible to prevent this. If the public wants to stamp out the disease it can do it by individual preservation. It is going to be impossible to quarantine every public gathering, for this would seriously cripple essential industries. . . the best thing to do is to avoid public gatherings as much as possible, walk to work in the morning rather than be exposed to a crowded conveyance [such as a trolley].”[6]

On Tuesday, October 1st, State Health Officer Dr. James Hayne tried to calm the public by downplaying the threat. “The disease itself is not so dangerous: in fact, it is nothing more than what is known as 'Grippe'. . . . The danger lies in the careless spreading of the disease, and careless treatment, allowing pneumonia or other dangerous maladies to develop.” Besides advising people to use common-sense and to exercise caution in their personal habits, Dr. Hayne recommend getting the flu vaccine in tablet form, which in fact did not yet exist for the strain in question.[7]

On Tuesday, October 1st, State Health Officer Dr. James Hayne tried to calm the public by downplaying the threat. “The disease itself is not so dangerous: in fact, it is nothing more than what is known as 'Grippe'. . . . The danger lies in the careless spreading of the disease, and careless treatment, allowing pneumonia or other dangerous maladies to develop.” Besides advising people to use common-sense and to exercise caution in their personal habits, Dr. Hayne recommend getting the flu vaccine in tablet form, which in fact did not yet exist for the strain in question.[7]

In Charleston, City Health Officer Dr. John Mercier Green issued a communication on October 1st asking every physician in the city to report to him the number of influenza cases under their care, and the number of deaths, if any.[8] The local population was aware of the flu’s deadly potential, but its presence within the city was not yet a major concern. On Thursday, October 3rd, for example, Governor Richard Manning and a host of military and civilian officials stood in Marion Square to watch hundreds of soldiers and patriotic citizens parade down King Street in support of a Liberty Loan drive to raise money for the war effort.[9]

The patriotic mass gathering on the morning of October 3rd was followed by an afternoon of mixed messages. The College of Charleston, whose male-only students participated in military training courses, suspended all activities that day and disbanded the student body. Speaking with reporters later that evening, Dr. Green said that local physicians had reported “about 350” cases of influenza to him, and just one death so far. Young children were at risk just like college boys, of course, so Dr. Green stated that the local school commission had promised to direct school principals to send children home if they displayed flu symptoms. School officials likewise asserted that “the public schools of this city are in no way affected by the ‘flu’,” and would continue to operate as usual.[10] Meanwhile, a telegram arrived from Atlanta announcing that the Southern division of the American Red Cross had appointed a local director general of civilian relief to prepare for an impending epidemic in Charleston, and to hire nurses with any level of medical training to assist their activities.[11]

Local physicians continued to report flu cases to the City Health Officer during the early days of October 1918. In a later report, Dr. Green recalled that as “great numbers of cases began to pour in and were recorded, a watchful eye was kept on the situation, as it was becoming alarming.” On the afternoon of Saturday, October 5th, the Charleston Board of Health realized that the rapid spike in cases warranted a drastic response. “The situation was so bad,” said Dr. Green, “that quarantine measures were absolutely necessary in order to stop its devastating effects and spread.” After consulting with a colleague from the U.S. Public Health Service, Dr. Green and his staff drew up quarantine regulations and issued a proclamation affecting everyone within the City of Charleston. Effective immediately, all activities involving groups of more than four or five people were to be discontinued until further notice. This prohibition included services in all churches and Sunday schools, public and private schools, theatres, movie houses, pool rooms, public and private dances, secret and fraternal associations, sewing circles, card parties, and all other places and forms of congregation.[12]

Beginning on the morning of Sunday, October 6th, the people of Charleston obeyed the public order and generally stayed at home. Business and hotels remained open, but were required to close by sundown. Electric trolleys continued to ply the street rails, but were required to keep their windows open and to limit the number of passengers per car. To enforce such regulations and closures, city officials were obliged to patrol downtown Charleston alongside the police force. “The whole energy of the [City Health] Department was exerted in trying to keep down and prevent the spread of this disease,” recalled Dr. Green, “all other work being practically stopped. . . . [The staff] all sacrificed everything, not caring for prescribed hours of working, they busied themselves trying to keep crowds from gathering in stores, and on the streets, and in seeing that quarantine regulations were being carried out. . . . All theatres, moving picture houses, poolrooms, schools were closed without a murmur or a word. . . . The behavior and spirt of the citizens was remarkable, they met us in a hearty co-operation and endeavored to assist us in enforcing the regulations.”[13]

At the same time, cities and town across South Carolina sought to check the spread of Spanish Flu in their communities by issuing similar quarantine orders. On the afternoon of Monday, October 7th, the State Board of Health issued an order for an immediate general quarantine across the Palmetto State. State Health officer Dr. James A. Hayne, following instructions from Surgeon General Rupert Blue in Washington, D.C., called on all citizens to keep to their homes and to cease gathering at schools, churches, moving picture houses, theaters, and any other place, and urged caution to avoid overcrowding in businesses, hotel lobbies, and all forms public transportation. In rural areas across the state, county sheriffs and their deputies were responsible for patrolling their communities to enforce compliance with the general quarantine.[14]

Owing to the international war then raging in Europe, however, Charleston’s Board of Health made exceptions for all activities related to a national fund drive called the “fourth Liberty Loan.” Committee meetings and door-to-door canvasing for donations continued without interruption across the city, no doubt exposing scores of citizens to the risk of infection. While activities such indoor funeral services and playground activities were forbidden, Health Officer Dr. J. Mercier Green considered the Liberty Loan work to be essential. The moneys collected by local volunteers, including large numbers of women, said Dr. Green, “were absolutely necessary for the winning of the war,” and were thus “expressly exempted from the provisions of the [quarantine] order.”[15]

In the early days of Charleston’s urban quarantine, Dr. Green recalled that “cases began to be reported to the office by the hundreds, and each day brought an increase in the number.” A number of local physicians and nurses were overseas in 1918, serving in either in the Army or Navy, so the city faced a critical shortage of trained healthcare workers. “Many hundreds were unattended by either physician or nurse,” said Dr. Green, “whole families were stricken, no one to look after them, they suffered from lack of attention, lack of food, medicine and clothing. Many hundreds suffered in this manner, and death took an easy toll.” The young and healthy succumbed to the Spanish Influenza just as easily as did the elderly and weak. Dr. Green observed that this particularly virulent strain of flu “seemed to have a predilection for the ages from 20 to 40 years.” In the absence of proper care and medical attention, the onset of pneumonia often caused fatal complications. “Pregnant women suffered particularly, and many died or else it caused them to abort.”[16]

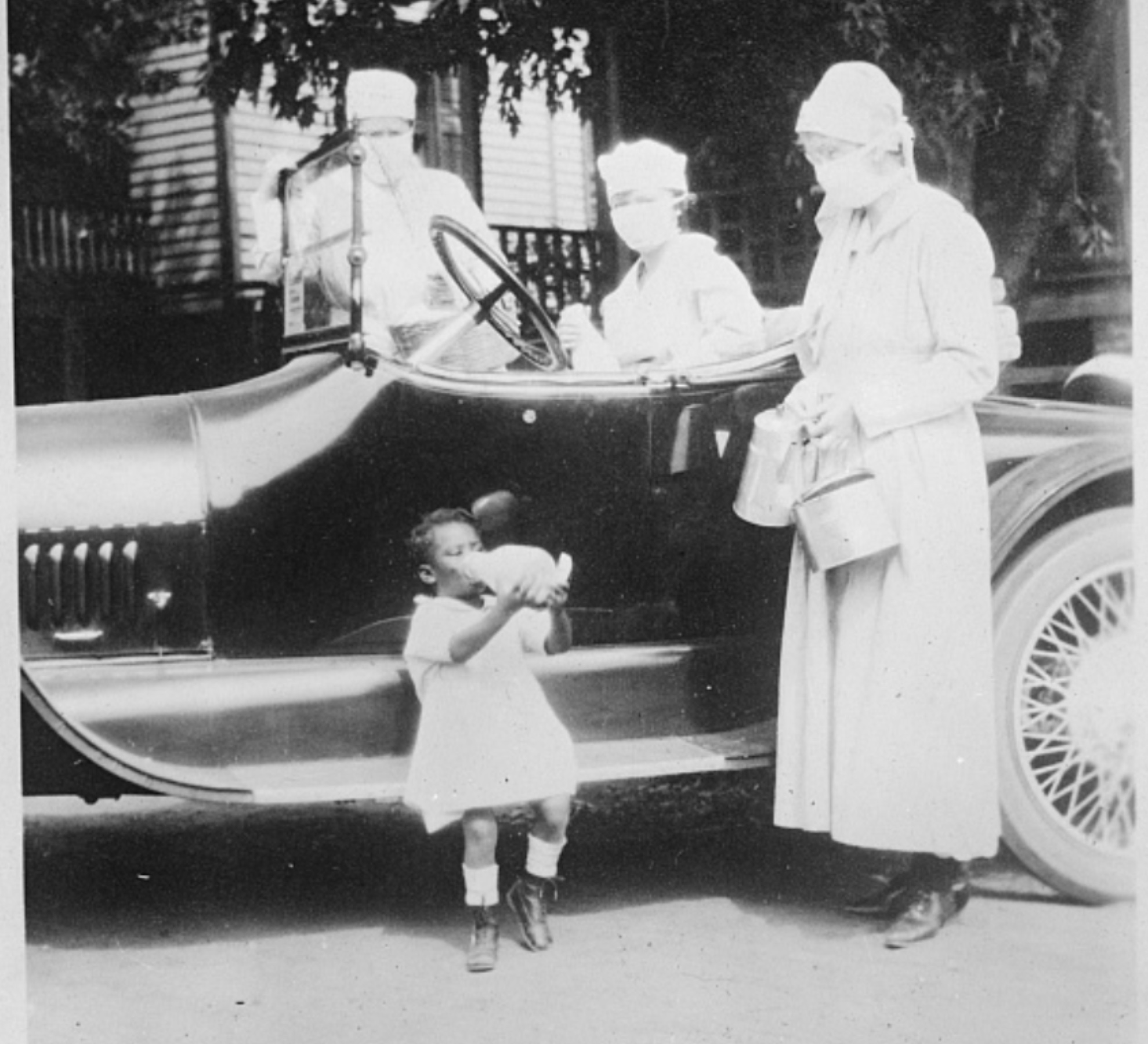

To fill the deficiency of local health care workers, the volunteer women forming the local chapter of the American Red Cross shouldered the lion’s share of the burden. Working in coordination with the local officers of the U.S. Public Health Service, the Red Cross performed what Dr. J. Mercier Green described as “a most notable and heroic work. . . . administering to the sick, and suffering, endeavoring to fill their every want with medicine, food and clothing.” Having already hired every available woman with medical training for paid temporary work, the Red Cross on October 10th called for supplemental volunteers without any medical training or experience, as the local need was “very urgent.”[17]

It’s important to remember that all health care services in early-twentieth-century Charleston were segregated according to local customs and laws during the era of Jim Crow politics. The heroic work of the Red Cross and other agencies during the influenza pandemic of 1918 flowed in two streams, therefore, extending separately to both the white and black communities. The white-owned newspapers of that era, which survive and provide valuable historical information, contain little information about relief efforts in the black community, while copies of Charleston’s early black-owned newspapers have not survived. We have, therefore, precious little data about the effects of the Spanish flu within African-American households across the city. During my recent investigations, however, I found a few references to Dr. Hulda Prioleau, Charleston’s first African-American female physician, who worked with white officials to coordinate Red Cross activities among the city’s black population. Similarly, registered nurse Anna DeCosta Banks, who was employed by the Ladies Benevolent Society, made hundreds of visits to black patients across Charleston throughout the epidemic.[18]

It’s important to remember that all health care services in early-twentieth-century Charleston were segregated according to local customs and laws during the era of Jim Crow politics. The heroic work of the Red Cross and other agencies during the influenza pandemic of 1918 flowed in two streams, therefore, extending separately to both the white and black communities. The white-owned newspapers of that era, which survive and provide valuable historical information, contain little information about relief efforts in the black community, while copies of Charleston’s early black-owned newspapers have not survived. We have, therefore, precious little data about the effects of the Spanish flu within African-American households across the city. During my recent investigations, however, I found a few references to Dr. Hulda Prioleau, Charleston’s first African-American female physician, who worked with white officials to coordinate Red Cross activities among the city’s black population. Similarly, registered nurse Anna DeCosta Banks, who was employed by the Ladies Benevolent Society, made hundreds of visits to black patients across Charleston throughout the epidemic.[18]

Red Cross workers visiting Charleston households soon recognized that the combination of influenza and quarantine conditions was having a negative effect on local nutrition. Eating a healthy diet was important for maintaining one’s strength, but many of the women responsible for preparing food for their respective families were incapacitated by the disease. When wives and mothers were too weak to shop for groceries or to cook meals, they and their families went hungry. To arrest this disturbing trend, the ladies of the local Red Cross established on October 14th what they called a “diet kitchen” in the domestic science hall of Memminger Normal School, at the corner of Beaufain and St. Philip Streets.

Under the executive supervision of Mrs. R. S. Cathcart (Katherine Julia Morrow Cathcart), dozens of ladies volunteered in three daily shifts to feed the hungry, flu-stricken families of Charleston. Graduates of courses in dietetics planned menus while others procured bulk comestibles, prepared dishes, arranged delivery boxes, and delivered hot meals by automobile. “The mid-day meal is the substantial one of the day,” said Mrs. Cathcart, but the Red Cross provided breakfast at 10 a.m., dinner at 2 p.m., and supper at 6 p.m. every day for the remainder of the quarantine. Visiting physicians and nurses recommended families in need to the Red Cross, the but the volunteer agency also welcomed telephone calls for assistance. Their food service was strictly free of charge, but those with the means to pay were encouraged to make donations to the agency after they had recovered.[19]

Despite their heroic efforts, Red Cross staff and volunteers soon felt overwhelmed by the number of cases spread across the landscape of urban Charleston. On the morning of October 16th, they sought to maximize their impact by devising a logistical strategy. Red cross officials divided the city into six districts and in each appointed a headquarters and one registered nurse. Each district nurse supervised a squadron of volunteer women who visited sick families and provided the most basic care. “The workers need not be trained, or even experienced in nursing,” said the Red Cross in its appeal for volunteers. “The only requisite is a love for her neighbor and an ability to crack ice, hand a glass of water or cook or heat nourishment for the sick. Gowns, caps and masks will be provided by the Red Cross, and the nurse in charge will instruct the workers in these and all other ways to protect themselves from contagion.”[20]

The spread of influenza across the urban landscape of Charleston in 1918 was not evenly distributed. The southernmost part of the city, south of Broad Street, was the least congested of Charleston’s neighborhoods and was populated largely by affluent white residents who could provide for their own needs. In contrast, the poor residents living in a crowded “mill village” adjacent to the Royal bagging factory in Charleston’s Ward No. 10 represented the city’s principal cluster of need. (This industrial village is now the campus of the Charleston Charter School for Math and Science.) Here the Red Cross established a supply depot and kitchen in the Sunbeam Memorial building, from which the resident district nurse and volunteer ladies distributed food, medicine, and all forms of medical attention. After their first week of activity, the Red Cross workers at Memminger School and the Sunbeam building had prepared and delivered 2,300 meals to influenza patients across the city.[21]

The scourge of Spanish Influenza in 1918 was amplified by the onset of pneumonia in many patients, which often led to a fatal conclusion. To fight pneumonia, many South Carolina physicians traditionally advised patients to drink small quantities of whiskey or brandy, but those intoxicating spirts were not legally available in 1918. The state of South Carolina had adopted a state-wide prohibition on the sale of alcohol in 1916 and strengthened its anti-liquor law when the U.S. entered the European war in 1917. Years before the national prohibition mandated by the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution came into force in 1920, there was no legal means of obtaining medicinal whiskey in the Palmetto State. At the same time, various law enforcement agencies often held vast supplies of confiscated liquors behind locked doors.

On October 12th, State Health Officer Dr. James Hayne urged Governor Richard Manning to allow state prohibition officials to release some of the state’s supply of confiscated whiskey to the various chapters of the Red Cross across the state: “In view of the serious situation with reference to the pneumonia cases following influenza, and the belief among some of the medical profession that whiskey or brandy is beneficial in the treatment of pneumonia in adults and children, it is advised that a certain portion of the confiscated whiskey or brandy now held by the state be turned over to the Red Cross chapters in South Carolina, this whiskey or brandy to be given out by the chapters only upon prescription by reputable physicians for such cases as are investigated and recommended by the chairman of the civilian relief committee of the Red Cross chapters or his recognized deputies.”[22]

On October 12th, State Health Officer Dr. James Hayne urged Governor Richard Manning to allow state prohibition officials to release some of the state’s supply of confiscated whiskey to the various chapters of the Red Cross across the state: “In view of the serious situation with reference to the pneumonia cases following influenza, and the belief among some of the medical profession that whiskey or brandy is beneficial in the treatment of pneumonia in adults and children, it is advised that a certain portion of the confiscated whiskey or brandy now held by the state be turned over to the Red Cross chapters in South Carolina, this whiskey or brandy to be given out by the chapters only upon prescription by reputable physicians for such cases as are investigated and recommended by the chairman of the civilian relief committee of the Red Cross chapters or his recognized deputies.”[22]

Governor Manning consulted with the state attorney general and on October 13th concurred with Dr. Hayne’s suggestion—as long as the intoxicants were handled exclusively by the Red Cross and used exclusively for the treatment of pneumonia. Charleston’s Mayor, Tristram Hyde, worked with local law enforcement authorities to facilitate the transfer of confiscated liquor to the local Red Cross, who deputized Health Officer Dr. J. Mercier Green to act on their behalf. The city’s chief of police, Captain Joseph Black, immediately released all whiskey held at the Station House on Vanderhorst Street, and Judge Henry Augustus Middleton Smith ordered the local Federal reservoir of liquor to be turned over to Dr. Green. Supplies were limited, however, as thousands of gallons of bootleg booze had recently been poured into the local sewer system in compliance with state law.[23]

Having commandeered the local liquor supply, the city’s Health Department set up a temporary dispensary system by which influenza patients could obtain a pint or a quart at a time, depending on the size of their family, with a prescription issued by a local physician. Demand for the intoxicating liquid was great, but supplies and patience were in short supply. A number of citizens complained that they could offer their sick children only a few drops of medicinal whiskey while state officials wasted enormous quantities of the valuable stuff. Others complained about the necessity of leaving work to wait for hours in long lines at the dispensary. Some white customers even complained about having to wait in line with Negroes, and demanded that the city segregate its temporary liquor distribution system.[24]

The number of influenza cases in the City of Charleston reached a peak around the middle of October, the 15th through the 17th, and then began to decline. At the same time, the number of deaths increased during the latter part of the month as pneumonia set in among existing patients and carried them to a mortal end. By October 21st, Dr. Green reported an official count of 5,064 cases of influenza and 130 deaths within the city limits, although privately he believed over-worked physicians were drastically under-reporting the number of cases under their care.[25]

State officials in Columbia observed a similar decrease in flu cases across South Carolina and began to talk of lifting the general quarantine. On October 28th, Charleston Health Officer Green wrote to the state Board of Health asking permission to continue the quarantine in the Palmetto City for a few days longer. His request was approved, as were similar requests from several other local health officials across the state. Following a conference in Columbia on October 31st, the State Board of Health announced that the statewide quarantine would end at dawn on Sunday, November 3rd, in thirty-eight of the state’s then-forty-five counties (including Charleston County). Within the urban limits of the City of Charleston, however, Dr. J. Mercier Green would determine when to cancel the existing restrictions.[26]

“By November things looked much brighter,” recalled Dr. Green. “The number of cases had greatly declined, also the deaths from pneumonia had fallen off to almost none.” On Monday, November 4th, Dr. Green announced that Charleston’s city-wide quarantine would end at midnight at the end of Wednesday, November 6th. On the morning of Thursday, November 7th 1918, Charleston began to return to normal. Movie theaters, pool halls, bars, restaurants, and all other businesses opened their doors and welcomed healthy customers. The city’s private schools, including the College of Charleston, Ashley Hall, Porter Military Academy, Bishop England, and others, also reopened on November 7th, but the city’s public schools, which served a much larger number of children, were not allowed to reopen until Monday, November 11th.[27]

The Red Cross “diet kitchen” at the Memminger School prepared its last meals on the evening of Wednesday, November 6th, and then scrubbed the last of the pots and pans.[28] Over a period of twenty-three and a half days, the volunteer kitchen crew, staffed by approximately fifty women, had prepared and served 5,677 meals (approximately 242 meals a day) “to all classes and conditions of people.”[29]

The Red Cross “diet kitchen” at the Memminger School prepared its last meals on the evening of Wednesday, November 6th, and then scrubbed the last of the pots and pans.[28] Over a period of twenty-three and a half days, the volunteer kitchen crew, staffed by approximately fifty women, had prepared and served 5,677 meals (approximately 242 meals a day) “to all classes and conditions of people.”[29]

Quarantine conditions endured for a few days longer at the Charleston Naval Training Camp, the site of the first cases in the local area. Having first closed its borders on September 17th, the Training Camp lifted its quarantine on Monday, November 11th. That morning, scores of naval cadets crowded into streetcars and trucks to get to Charleston as quickly as possible. The townsfolk were, for the most part, now healthy and happy, and were preparing a massive celebration. The Great War, which had dominated news headlines over the past few years, was now officially over. Thousands of citizens lined the streets to cheer the news of an armistice in Europe, and waves of soldiers and sailors in uniform paraded proudly through the triumphant city.[30]

The end of the quarantine did not mean the end of the Spanish Influenza in Charleston. Writing his official report for the mayor on January 1st, 1919, Dr. J. Mercier Green noted that the flu continued to claim new victims through the rest of November and December. Although its spread was no longer of epidemic proportions, he predicted the disease would persist locally through the end of the winter months. Within the city limits, the Charleston Board of Health recorded an official total of 7,154 flu cases, resulting in a total of 291 deaths. Confident that exhausted physicians had under-reported their case load to him, Dr. Green offer a “conservative estimate” that the real number of cases of Spanish Flu in urban Charleston was “easily between 15,000 and 18,000.”[31]

According to the official numbers, therefore, the 1918 flu affected approximately 10% of Charleston’s urban community, while unofficially the number was probably closer to 20%. Owing to the temporary, war-time spike in population, however, it’s difficult to pinpoint the precise ratio of mortality within the city. Whether we estimate the local population at 61,000 or 85,000, the 1918 flu claimed between .03% and .05% of Charleston residents. In November 1918 the State Bureau of Vital Statistics reported that they had received official reports of 87,415 cases across South Carolina, but the actual number was estimated at 116,000 among the state’s population of just over 1.5 million inhabitants. In the month of October—the peak of the epidemic—a total of 4, 274 people died of influenza in South Carolina, including civilians and soldiers. The state’s most populous county, Charleston, also hosted the largest number of cases and deaths.[32]

Looking back at the epidemic of 1918, City Health Officer Dr. J. Mercier Green observed that the Spanish Influenza descended on the City of Charleston so rapidly that “it was really upon us before we were aware that it was epidemic.”[33] In the months that followed this health crisis, local officials tried to marshal their experiences into better preparation for similar events in the future. State legislators clamored for increased healthcare spending, especially for child health services, across South Carolina. Closer to home, the flu epidemic of 1918 led to the creation of the Charleston County Health Department in the spring of 1920. Dr. Leon Banov, a junior officer in the city’s health department during the influenza crisis, headed the new agency and oversaw its eventual merger with the older city department.[34]

In his report filed in the aftermath of the 1918 epidemic, Dr. Green stated with conviction that “there has never been any disease in the history of the city which has equaled the death toll taken by this disease and its complications during the present epidemic.”[35] While Dr. Green was certainly a skilled physician and public health officer, his knowledge of Charleston history was not quite up to par. In fact, Charleston has, on several occasions in the distant past, suffered epidemics of disease and death that overshadow the scourge of 1918. But we’ll save the horror stories of 1699, 1738, 1760, and other years for future episodes. In the meantime, keep calm and read!

Check out the Charleston essay from the University of Michigan’s Influenza Encyclopedia.

Read Hanna Raskin’s recent article about the Influenza epidemic of 1918 in the Charleston Post and Courier.

[1] J. Mercier Green, “Report of Health Officer,” Department of Health, 1 January 1919, in City of Charleston, Year Book, 1918, page 175.

[2] Green, “Report,” 164.

[3] Charleston Evening Post [hereafter Evening Post], 18 September 1918, page 11, “The Spanish Flu at Training Camp.”

[4] Evening Post, 19 September 1918, page 9: “Spanish Flu Is Under Control.”

[5] Charleston News and Courier [hereafter Courier], 30 September 1918, page 8, “Citadel Closes.”

[6] The State [Columbia, S.C.; hereafter State], 1 October 1918, page 2: “Individuals Can Stop Influenza.”

[7] State, 2 October 1918, page 10: “Hayne Tells How to Prevent Influenza.”

[8] Courier, 2 October 1918, page 10, “Influenza Cases Must Be Reported.”

[9] Courier, 2 October 1918, page 10: “Parade Streets for People Only.”

[10] Courier, 4 October 1918, page 8, “College Closes for the Present”; Evening Post, 30 September 1918, page 4, “No General Sway of Flu Locally.”

[11] Courier, 4 October 1918, page 6, “Red Cross to Help Fight Influenza.”

[12] Green, “Report,” 165–66; Courier, 6 October 1918, page 10, “Churches, Theaters, Lodges and Schools Are Ordered Closed”; Leon Banov, As I Recall: The Story of the Charleston County Health Department (Columbia, S.C.: R. L. Bryan, 1970), 22.

[13] Green, “Report,” 170; Courier, 7 October 1918, page 8, “Board of Health’s Mandate Is Obeyed”; Courier, 9 October 1918, page 7, “Flu Affects the Cars”; Banov, As I Recall, 23.

[14] Courier, 8 October 1918, page 1, “Statewide Order for Quarantine”; Evening Post, 10 October 1918, page 8: “216 New Cases of Flu Reported.”

[15] Green, “Report,” 165–66; Courier, 6 October 1918, page 10, “Churches, Theaters, Lodges and Schools Are Ordered Closed;” Courier, 9 October 1918, page 8, “Health Officer Explains Order.”

[16] Green, “Report,” 166–67; Courier, 20 October 1918, page 10, “All Doctors Here Work to the Limit.”

[17] Green, “Report,” 166; Courier, 10 October 1918, page 2, “Nurses Needed at Home”; Evening Post, 11 October 1918, page 11, “Local Red Cross Rendering Aid.”

[18] Evening Post, 6 November 1918, page 11, “Diet Kitchen Closes Tonight”; Courier, 21 November 1918, page 10, “Red Cross Chapter Chooses Officers”; Evening Post, 14 November 1918, page 6, “The Benevolent Society.”

[19] Courier, 14 October 1918, page 8, “Red Cross Calls on Women to Help”; Evening Post, 17 October 1918, page 4, “Diet Kitchen Is Busy Center.”

[20] Evening Post, 16 October 1918, page 6, “City Organized into Districts”; Courier, 17 October 1918, page 3, “City Districted to Fight Epidemic.”

[21] Courier, 17 October 1918, page 3, “City Districted to Fight Epidemic”; Evening Post, 11 October 1918, page 11, “Local Red Cross Rendering Aid”; Evening Post, 23 October 1918, page 7, “2,300 Meals have been served here.”

[22] Courier, 13 October 1918, page 11, “No Abatement of ‘Flu’ In This State.”

[23] Courier, 14 October 1918, page 2, “Whiskey to Treat Pneumonia Cases”; Courier, 14 October 1918, page 8, “Constables Here Lacking Whiskey”; Courier, 17 October 1918, page 5, “Whiskey for the Flu Sufferers”; Green, “Report,” 167–68.

[24] Charleston News and Courier, 31 October 1918, page 3, “Getting Quart of Liquor”; Green, “Report,” 167–68.

[25] Green, “Report,” 168–69; Charleston News and Courier, 22 October 1918, page 10, “Flu Quarantine to Last a While.”

[26] Courier, 29 October 1918, page 8, “Flu Quarantine Won’t End Sunday”; State, 1 November 1918, page 12, “Quarantine Stays on Seven Counties”; Green, “Report,” 168.

[27] Courier, 5 November 1918, page 8, “Flu Quarantine Ends Tomorrow”; Courier, 11 November 1918, page 8, “Public Schools Will Open Today”; Green, “Report,” 168.

[28] Evening Post, 6 November 1918, page 11, “Diet Kitchen Closes Tonight.”

[29] News and Courier, 15 November 1918, page 8, “To Furnish Record for the Red Cross.”

[30] Evening Post, 11 November 1918, page 5, “Sailors Freed from Quarantine,” and “Great Parade As Climax to Day’s Program”; Courier, 12 November 1918, page 10, “Remarkable Scenes Before Dawn When Charleston Gets the News of the Signing of the Armistice.”

[31] J. Mercier Green, “Report of Health Officer,” Department of Health, 1 January 1919, in City of Charleston, Year Book, 1918, page 169–71.

[32] Evening Post, 20 November 1918, page 10, “87,415 Flu Cases during Epidemic.”; Evening Post, 3 December 1918, page 6: “3,591 Die of Flu during October.” The total number reported at that time included 3,591 deaths among the general population, 354 deaths at Camp Jackson in Columbia, and 329 deaths at Camp Sevier at Greenville, but it did not include deaths at Camp Wadsworth in Spartanburg.

[33] J. Mercier Green, “Report of Health Officer,” Department of Health, 1 January 1919, in City of Charleston, Year Book, 1918, page 165.

[34] Courier, 21 December 1918, page 1, “Board of Health Wants Outlined”; Banov, As I Recall.

[35] J. Mercier Green, “Report of Health Officer,” Department of Health, 1 January 1919, in City of Charleston, Year Book, 1918, page 165.

PREVIOUS: Yamboo: An Enslaved Muslim in Early South Carolina

NEXT: The Scandalous Black Dance of 1795, Part 1

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments