Oqui Adair: First Chinese Resident of South Carolina, Part 2

Processing Request

Processing Request

Oqui the Chinese gardener travelled to the United States in 1855 and spent two years practicing his trade at the nation’s Botanic Garden in Washington, D.C. Seeking a more familiar climate, he accepted an invitation to migrate southward and create a unique plantation garden on Edisto Island, South Carolina. The violence of Civil War forced Oqui to flee his fertile seaside garden in 1861, but he soon found a new career at the Insane Asylum in the capital city of Columbia, where he raised a family and spent his final days.

Let’s begin with a quick recap of the first half of Oqui’s story. Dr. James Morrow of South Carolina sailed to Hong Kong in 1853 as the designated botanist or agriculturalist of a diplomatic mission sent by President Millard Fillmore. As part of an entourage led by U.S. Navy Commodore Matthew C. Perry, Dr. Morrow visited Japan in early 1854 and collected hundreds of varieties of native plants for scientific study. The American entourage returned to Hong Kong later that summer, and in August Commodore Perry hired a young Chinese gardener named Oqui from the Parsee Cemetery in Macau to help Dr. Morrow prepare the live plants for passage back to the United States. Oqui and his American companions departed from Hong Kong in September 1854 and arrived in New York five months later. After removing their large collection of live plants to Washington D.C. in March, 1855, twenty-year-old Oqui began a new career as an employee at the United States Botanic Garden near the U.S. Capitol Building, while James Morrow returned to his home in South Carolina.

The physician and amateur botanist steamed from Washington to Charleston in the spring of 1855, and then continued by train to his home in Willington, Abbeville District (now part of McCormick County). Before leaving the Palmetto City, however, Dr. Morrow deposited with his colleagues in the South Carolina Institute some of his “Japanese curiosities” for display at the institution’s fifth-annual fair, held at their recently-completed “Institute Hall” on Meeting Street in April 1855. Visitors to the fair were intrigued and fascinated by the samples of Japanese textiles, ceramics, and woodworking, and complemented the thirty-five-year-old doctor on the success of his recent Asian adventure.[1]

But Dr. Morrow was distracted with anxiety about his travels to China and Japan. His voluntary participation in the government-sponsored expedition had been motivated by scientific curiosity rather than profit, and he had expended a large amount of his own money during the two-year voyage. Hoping to gain some form of compensation from the Federal government, Morrow drafted a memorial summarizing his scientific contributions to the expedition and submitted it in the spring of 1856 via an elected representative to the U.S. Congress. Among his accomplishments in the Orient, Morrow mentioned that he had “selected and brought home to the United States, a young Chinese gardener, skilled as he [Morrow] had every assurance in all the arts of Chinese gardening, grafting, dwarfing, bouquet-making, fish raising, &c.” “This boy, ‘Oqui,’” wrote Morrow in 1856, “is now employed in the hot-houses near the capital.”[2]

Some months after James Morrow forwarded his memorial to Congress, he returned to Washington D.C. in January 1857 to lobby for the passage of a bill to render payment for his service in China and Japan. During his sojourn to the nation’s capital, it appears that he visited his former colleague, Oqui, at the U.S. Botanic Garden. Dr. Morrow likely admired the landscaping that Oqui and his colleagues had created around the principal greenhouse—sinuous gravel walkways bordered with boxwood, winding through “a labyrinthian garden, where, on all sides, the senses are agreeably saluted by the grateful perfume and variegated colors of rare and beautiful flowers of infinite variety.”[3] Morrow, no doubt, praised the beautiful scenery and complemented the young Chinese gardener on his American accomplishments. But Oqui was not content with his new life in the nation’s capital. According to a later family story, Oqui told the doctor that he was not satisfied with Washington. The climate did not suit him, and he was contemplating making the long journey back to China.[4] Dr. Morrow’s reaction to this news is unknown, but his conversation with Oqui remained in his memory after the two men parted.

Some months after James Morrow forwarded his memorial to Congress, he returned to Washington D.C. in January 1857 to lobby for the passage of a bill to render payment for his service in China and Japan. During his sojourn to the nation’s capital, it appears that he visited his former colleague, Oqui, at the U.S. Botanic Garden. Dr. Morrow likely admired the landscaping that Oqui and his colleagues had created around the principal greenhouse—sinuous gravel walkways bordered with boxwood, winding through “a labyrinthian garden, where, on all sides, the senses are agreeably saluted by the grateful perfume and variegated colors of rare and beautiful flowers of infinite variety.”[3] Morrow, no doubt, praised the beautiful scenery and complemented the young Chinese gardener on his American accomplishments. But Oqui was not content with his new life in the nation’s capital. According to a later family story, Oqui told the doctor that he was not satisfied with Washington. The climate did not suit him, and he was contemplating making the long journey back to China.[4] Dr. Morrow’s reaction to this news is unknown, but his conversation with Oqui remained in his memory after the two men parted.

Congress and President Franklin Pierce ratified the bill to compensate James Morrow in late February 1857, after which the doctor returned to Charleston.[5] Some weeks later, Morrow was in Columbia, the capital of South Carolina, where he met an old friend. John Ferrars Townsend (1799–1881), Speaker of the State House of Representatives, informed the doctor that he was looking for a gardener to work at his plantation on Edisto Island. Morrow recommended to Townsend his Chinese colleague, Oqui, whom he had first met in Macau several years earlier and who accompanied him back to the U.S. Botanic Garden. Oqui was unhappy in Washington, however, and was now considering a return to his native land. Perhaps an invitation to work within the warmer climate of a South Carolina sea-island might tempt him to remain in the United States.[6]

John Townsend was a long-time member of the South Carolina legislature, representing Charleston District, Parish of St. John, Colleton, serving as both a representative and senator. He was a member of the Board of Trustees for South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina), and an ardent defender of slavery and of States Rights. He and his wife, Mary Caroline Jenkins Townsend (1813–1889), raised several children on Edisto Island, but also traveled frequently by steamboat to nearby Charleston. Mr. Townsend’s legislative duties obliged him to spend part of his time in Columbia, and each summer the family retreated to the cooler mountains farther to the west.[7] According to an old family recollection, John Townsend followed his conversation with Dr. James Morrow by making a special trip to Washington, D.C., where he convinced Oqui to venture five hundred miles southward to Edisto Island.[8] The precise date of Oqui’s move to Edisto is unclear, but probably occurred during the spring or summer of 1857. By that autumn, for example, Mrs. Townsend teased Oqui about the rabbits who ate most of his garden peas.[9]

According to the 1860 Federal Census schedule of enslaved people in South Carolina, John Townend owned 272 enslaved men, women, and children working at several plantations on Edisto Island. Their chief employment was raising Sea Island cotton, a valuable, long-staple variety grown within the unique climate of the coastal barrier islands.[10] Bleak Hall, the family’s principal residence at the northeast end of Edisto Island, included a rambling three-story residence surmounted by a tall cupola, while the enslaved population lived in modest cabins among other agricultural outbuildings on the plantation. For Oqui the gardener, Mr. Townsend reportedly built at Bleak Hall “a house called ‘Celestials,’ modeled on his old home.”[11]

According to the 1860 Federal Census schedule of enslaved people in South Carolina, John Townend owned 272 enslaved men, women, and children working at several plantations on Edisto Island. Their chief employment was raising Sea Island cotton, a valuable, long-staple variety grown within the unique climate of the coastal barrier islands.[10] Bleak Hall, the family’s principal residence at the northeast end of Edisto Island, included a rambling three-story residence surmounted by a tall cupola, while the enslaved population lived in modest cabins among other agricultural outbuildings on the plantation. For Oqui the gardener, Mr. Townsend reportedly built at Bleak Hall “a house called ‘Celestials,’ modeled on his old home.”[11]

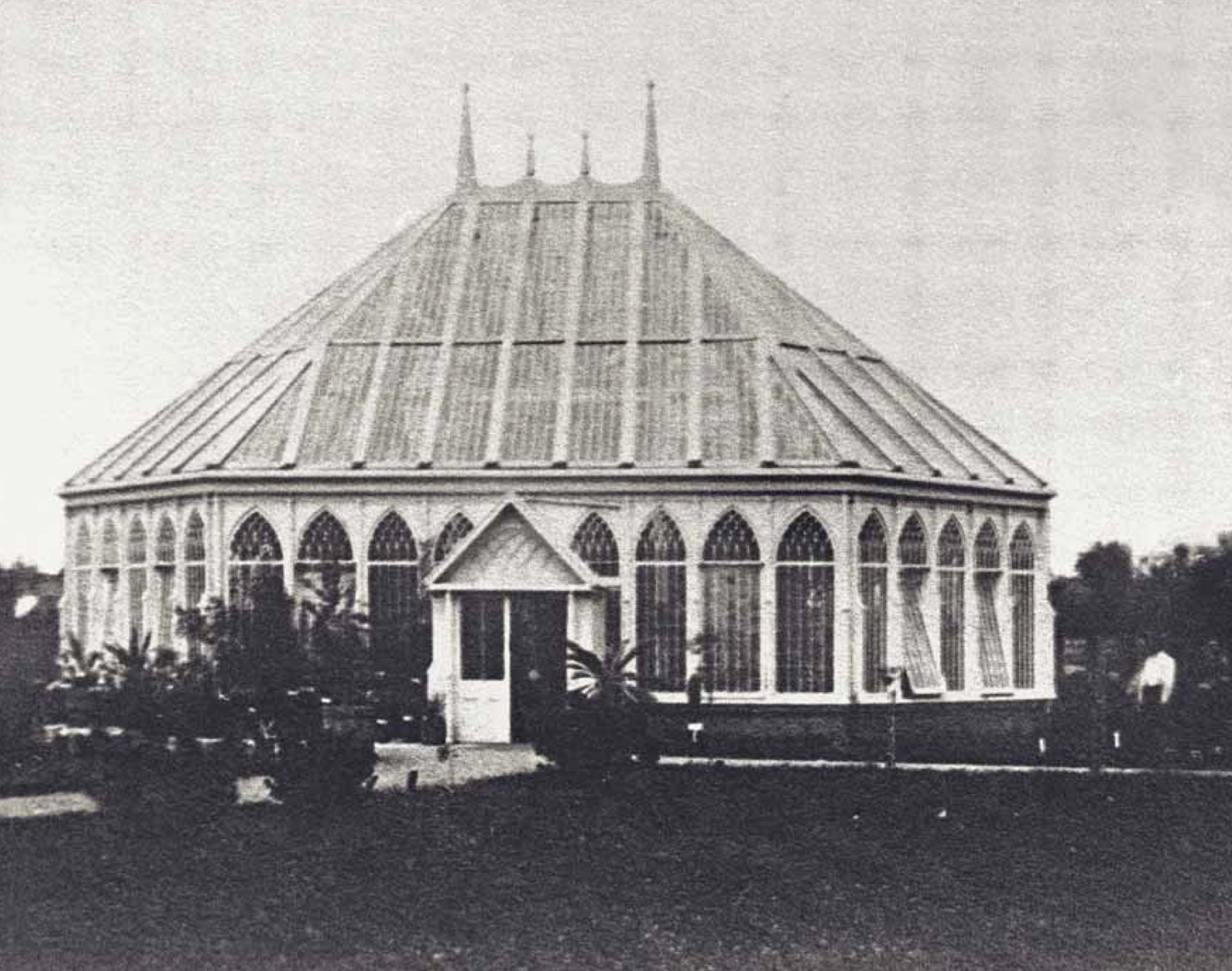

“Celestials” was a generic term frequently used in the United States during the mid-nineteenth century to describe Chinese immigrants. While it is possible that the house built for Oqui on Edisto Island might have featured some traditional Chinese architectural features, it is also possible that it might have been modeled on his previous home in Washington, D.C. Details of Oqui’s residence at the U.S. Botanic Garden are unknown, but it was sited near the government greenhouse built in 1850 in the Gothic-Revival style (which I mentioned in the first part of this story). Coincidentally, one of the few surviving antebellum structures at Bleak Hall is a curious, two-story, Gothic-Revival building with a high-pitched roof surmounted by three decorative spires. Now generally known as “the Ice House,” this old structure bears an uncanny resemblance to the mid-century greenhouse built in Washington.

Beyond the various houses, grand and plain, and the adjoining landscape devoted to agriculture, Bleak Hall was surrounded by an abundance of native wildlife. Nestled in a lush maritime forest of live-oak and palmetto trees one-half mile from the Atlantic shoreline, residents of the property would have seen a variety of fauna such as rabbits, snakes, terrapins, alligators, seagulls, shorebirds, pelicans, herons, egrets, ibises, and sea turtles. To impose order within this natural environment, the Townsend family employed Oqui to create a formal garden for their personal enjoyment. Anecdotes passed down through the generations have described the fruit of Oqui’s efforts as a Chinese- or Japanese-style garden, which was perhaps the first of its kind in the United States. Oqui did not accomplish this work on his own, however. He would have directed and worked alongside the enslaved men, women, and children of African descent who formed the overwhelming majority of the population on Edisto Island at the time. As a later islander recalled, “the slaves worked well under him, and vast sums were spent to make the garden a beautiful place.”[12]

A handful of Townsend family letters written at Bleak Hall in 1858 mention a variety of plants growing under Oqui’s supervision, but unfortunately do not describe the layout of the grounds. From these letters, we learn that he grew apples, pineapples, plums, pomegranates, begonias, carnations, golden coreopsis, gardenias, geraniums, jonquils, mimosas, myrtles, oxalis, roses, and tulips. In addition, Oqui tended a market garden that produced such vegetables as cucumber, peas, and okra.[13] A twentieth-century memoir of Edisto Island recalled that “the lovely white poppies that grow so luxuriantly on the islands along the South Carolina coast were first planted by Oqui’s hand. He also brought the yellow-blossomed Chinese tobacco plant, whose trumpet-shaped flower is a magnet for humming birds. He planted camphor, olive, and spice trees and bordered the large vegetable garden at Bleak Hall with sweet oranges. A house was built to store the oranges, with shelves filled with white beach sand along the walls, where the fruit could be buried and kept for months.”[14]

Oqui the young gardener was proud of the landscape he created and jealous of unwelcome visitors. During a spell of dry weather one October, for example, fresh water became scarce for the animals working on the plantation. In a letter to her daughter, Mrs. Townsend said “Oqui will have the horrors when he sees the horses carried through the garden to be watered.”[15] In February 1858, Mrs. Townsend related another “very amusing scene” involving a smaller mammal: “I heard Oqui in a great state of excitement holloing [sic] Shu! Shu! In a few moments, the dogs & little negroes with Oqui at their head, tore through the garden, this way & that in hot pursuit. A halt, and I saw Oqui raise a rabbit by the hind legs & pound its head with great spite on the ground. ‘The Labbit is too cunning, I poke the bush here & there[;] he sit & look at me with eyes wide open. Ah-ha! I say, I catch you, & when I put out my hand, he jump right over. He eat all my peas and all the carnations.’”[16]

Oqui the young gardener was proud of the landscape he created and jealous of unwelcome visitors. During a spell of dry weather one October, for example, fresh water became scarce for the animals working on the plantation. In a letter to her daughter, Mrs. Townsend said “Oqui will have the horrors when he sees the horses carried through the garden to be watered.”[15] In February 1858, Mrs. Townsend related another “very amusing scene” involving a smaller mammal: “I heard Oqui in a great state of excitement holloing [sic] Shu! Shu! In a few moments, the dogs & little negroes with Oqui at their head, tore through the garden, this way & that in hot pursuit. A halt, and I saw Oqui raise a rabbit by the hind legs & pound its head with great spite on the ground. ‘The Labbit is too cunning, I poke the bush here & there[;] he sit & look at me with eyes wide open. Ah-ha! I say, I catch you, & when I put out my hand, he jump right over. He eat all my peas and all the carnations.’”[16]

Oqui’s tenure at Bleak Hall with the Townsend family lasted for slightly less than four years. The beginning of the end of his employment there commenced in December 1860, when John Townsend travelled first to Columbia and then to Charleston to sign the South Carolina Ordinance of Secession.[17] Civil War erupted in Charleston harbor in April 1861, when local forces opened fire on the Federal troops stationed within Fort Sumter. Immediately after this violent schism, the United States Government began planning a large-scale offensive to blockade and neutralize the major ports of rebellious South Carolina. A fleet of U.S. Navy vessels steamed southward in the autumn of 1861 and in early November launched a major offensive at Port Royal Sound. Within a week’s time, Federal forces held the town of Beaufort and the neighboring sea islands. The capture of Edisto Island, just a few leagues to the north, was next on the government’s agenda.

A twentieth-century memoir of the Townsend family’s ordeal described the scene in the following words: “One day in November, 1861, a messenger rode in haste from house to house. The steamboat ‘Beauregard,’ sent by the Confederate government, was docked at the public landing, and the messenger carried an order for all those remaining on the island to evacuate. There was no time to gather up precious possessions and no means of taking them away. With only what they could carry, the planters’ families left their homes.”[18] Shortly thereafter, Federal Troops occupied Bleak Hall and transformed the garden landscape into a military encampment for the remainder of the war.[19]

The Townsends and Oqui, like all their White neighbors, fled their comfortable plantation life and steamed to Charleston, leaving behind the enslaved population to welcome the liberating troops of President Lincoln’s army. The Chinese gardener was likely residing in the Palmetto City with hundreds of other refugees when an apocalyptic fire swept across the city on December 11th, 1861, and multiplied the city’s housing crisis exponentially. John Townsend was still in Charleston in March 1862, however, when he attended a fancy dinner there to support a new militia unit called the Willington Rangers.[20] Whether his old friend, Dr. James Morrow of Willington was present is unclear, but both men retreated inland as the war progressed through the remainder of 1862. To house his family for the duration of the Civil War, John Townsend purchased a plantation near St. Matthews in Orangeburg County, approximately eighty miles northwest of Edisto Island and twenty-five miles southeast of Columbia. Civic duties periodically required his presence in the capital during the early 1860s, and Mr. Townsend might have introduced Oqui to Columbia in an effort to help the Chinese gardener find a new career.[21]

Although he was not then serving in the legislature, John Townsend probably heard from his political friends about the financial struggles of various public institutions. The state mental hospital, for example, then known as the South Carolina Insane Asylum, was in desperate need of funding. The war had inflated the cost of clothing and provisions for the inmates and staff, but supplies were short and most of the state’s budget was diverted to military operations.[22] To supplement the perpetually-meagre appropriations from the state government, the Board of Regents of the Insane Asylum had erected a greenhouse in 1849 and hired a gardener to raise flowers and other plants for retail sale.[23] Located one mile northeast of the statehouse grounds, on the perimeter of Columbia’s urban street grid, the Asylum’s greenhouse stood within easy reach of thousands of customers and fulfilled its financial purpose. The gardener was absent at the end of 1862, however, and the institution needed an experienced hand to generate much-needed revenue for the hospital.

On the 10th of January 1863, the superintendent of the South Carolina Insane Asylum engaged a new gardener for a three-month trial, pending the return of John White, an Irishman who had served as the institution’s gardener for the past several years.[24] The surviving records of the Asylum did not record the name of this temporary gardener, but the quality of his work apparently impressed the management. Three weeks after he began working at the Asylum, the Board of Regents voted to retain the interim gardener even if Mr. White returned before the end of his three-month trial. The Irishman did return several weeks later, forcing the board to decide which of the two men to employ on a permanent basis. At a meeting of the Board of Regents on March 7th, 1863, the secretary recorded that “an election was then held for Gardener which resulted in the unanimous decision for O Adair.”[25]

Oqui, the Chinese gardener who came to the United States in 1855, acquired the surname “Adair” at some point before the spring of 1863. The timing and motivation behind this additional nomenclature remains a mystery. He might have selected or received this Scots-Irish surname while working under the Scottish gardener, William R. Smith, at the U.S. Botanic Garden in Washington. The surname “Adair” was uncommon in Charleston and in South Carolina generally during Oqui’s early years in the state, but his adoption of the name might have been inspired by an element of contemporary pop culture. The eighteenth-century Irish ballad “Robin Adair” became very popular in Britain and the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century, and was heard in both public theaters and private drawing rooms for many years. It is possible, therefore, that members of the Townsend family blended the Chinese gardener’s two-syllable name with the popular song to form the cognate, “Oqui Adair.”

Oqui’s new position at the South Carolina Insane Asylum included accommodations on the grounds of the institution, but his predecessor, John White, refused to vacate the premises. On the 4th of July, 1863, after the former gardener had ignored previous instructions, the Board of Regents resolved “to inform Mr. White that unless he leaves the house he now occupies by the 15th of this month, legal measures will be taken for his ejection.”[26] Meanwhile, economic conditions at the Asylum continued to deteriorate as the Civil War dragged on. During this dark period of decline, Oqui drew from his experience at Bleak Hall to cultivate a large garden that likely included vegetables for the inmates and staff as well as exotic plants for sale. His cheerful attitude and diligent work impressed his superiors and brightened the troubled spirits of the men and women confined within the institution. In early November 1864, the superintendent of the South Carolina Insane Asylum, Dr. John W. Parker, praised Oqui’s work in his annual report to the Board of Regents:

“The green-house, garden and grounds about the Asylum are kept in good order by Oqui Adair, a Chinaman. By his exertions and faithfulness he has not only added to his stock of native and exotic shrubs and flowers, but, by the sale of such as could be spared from the garden without detriment, he has paid into your treasury four times the amount of his compensation, and, by his polite attention to the patients, he has made the green-house and garden places of pleasure and recreation to all interested.

The garden affords healthy recreation to such patients as are willing to enjoy it, and is cultivated, not so much with a view to pecuniary advantage as a curative and beneficial means in their moral treatment. It is wanting in quantity as well as quality of soil, to make it available in a pecuniary sense.”[27]

Immediately after the publication of the superintendent’s optimistic report, political pressure from the nearby statehouse threatened to encroach on Oqui’s pastorale landscape. Confederate officials had pressured state government throughout 1864 for permission to house prisoners of war within the Insane Asylum, but the institution’s managers succeeded in blocking a plan to quarter military prisoners within the psychiatric dormitories. In the final weeks of 1864, however, military authorities gained permission to use part of the Asylum’s large campus, enclosed by high walls, as a prison camp. In mid-December 1864, approximately 1,200 Union officers were corralled into a new facility called Camp Asylum.[28] Oqui witnessed the ragged prisoners incarcerated near his greenhouse and garden, and was perhaps relieved by their removal to North Carolina in mid-February 1865. The four-year war reached a dramatic climax three days after their departure, on February 17th, when another fire of apocalyptic proportions consumed most of the city of Columbia.

Neither the Insane Asylum nor its greenhouse perished in the conflagration of 1865, but the institution suffered during the ensuing depression that persisted across South Carolina during the post-war years. Damages to the greenhouse, caused by harsh weather and/or general wear-and-tear, constrained the volume of Oqui’s botanical production, but he remained congenial in the face of adversity. “The green house and flower gardens are places of pleasant resort for the patients,” said the superintendent, Dr. Parker, in 1868, and the gardener’s “polite attention to the inmates is duly appreciated.” The institution’s Board of Regents no doubt valued his service to the community as well. “Oqui Adair is always at his post to wait on the ladies,” said Dr. Parker, and the state’s lone Chinese resident likely met a number of eligible young women in the course of his professional duties.[29]

As I mentioned in the first part of Oqui’s story, he appears in the Federal Census of 1870 as a thirty-five-year-old bachelor, a citizen of the United States, residing at the South Carolina Lunatic Asylum with other employees of that institution. Sometime after that event, however, Oqui married a young woman of Dutch ancestry named Mary Elizabeth, who was a native of South Carolina and seven or eight years younger than him. How they met and when they married are questions not answered by available sources, but Oqui’s adoption of the Christian religion (as mentioned in his obituary) probably facilitated the matrimonial match. During the early 1870s, Mr. and Mrs. Adair welcomed three children, Ella, Belton, and Mary.[30] The family purchased a house in Columbia, then numbered 14 Elmwood Avenue, a short distance due west of the Asylum where Oqui was employed.[31]

For reasons unknown, Oqui Adair was in declining health during the early weeks of 1877. Twenty-two years had passed since he arrived by ship in New York Harbor, and he had spent more than half of his life in the United States. With the help of a local attorney, he made his last will and testament on February 3rd. Oqui stated that he owned “very little property,” including “a house and lot in Columbia where I now reside and some household furniture of small value,” all of which was to be shared by his wife and children.[32] He died on June 12th, 1877, aged approximately 42 years. The following day, a local newspaper published a brief but touching obituary:

“Mr. Oquir [sic] Adair, the Chinaman gardener, and the only representative of his race in Columbia, died in the city yesterday morning. Mr. Adair followed the business of a florist, and many of the sweet little girls of years ago (when he was in the height of his prosperity,) who have now budded into beautiful womanhood, will remember the kindly heart and polite manners of the Chinaman who never let them go away empty-handed when they came to him for flowers, and will regret to learn of his death. Mr. Adair married an American lady, became a Christian, and died in the faith. His funeral will take place this afternoon.”[33]

In the century and a half since his demise, the memory of Oqui Adair has faded among the people of his adopted country. My goal in tracing the outline of his biography is to draw attention to the human drama inherent in the experience of immigration, and to spark interest in his personal narrative. As a master gardener, Oqui’s contributions to the Perry Expedition of the 1850s, the United States Botanic Garden in Washington, D.C., Bleak Hall on Edisto Island, and the South Carolina Insane Asylum in Columbia, merit the appreciation of a grateful nation. South Carolina must be proud to claim Oqui Adair—a pioneer who declared himself an American on his arrival in 1855—as its first resident of Chinese ancestry. His name might be unfamiliar at the moment, but efforts to discover more about his life continue.

In recent months, I’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with individuals from the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources seeking to restore Oqui’s name to the landscape he once inhabited. The Townsend family residence at Bleak Hall Plantation did not survive the Civil War, but three outbuildings, vestiges of the formal garden created by John Townsend and Oqui Adair, remain standing more than a hundred and sixty years after they evacuated from Edisto Island. Later owners of Bleak Hall combined the property with adjacent tracts to create a larger entity called Botany Bay Plantation, encompassing more than 3,300 acres. In 1973, the three remaining outbuilding at Bleak Hall—including the Gothic-Revival “Ice House”—were added to the National Register of Historic Places. The State of South Carolina acquired this property, and in 2008 the Department of Natural Resources opened it to the public as the Botany Bay Heritage Preserve / Wildlife Management Area. Soon visitors to that beautiful preserve will learn more about the contributions of Oqui Adair.[34]

In recent months, I’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with individuals from the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources seeking to restore Oqui’s name to the landscape he once inhabited. The Townsend family residence at Bleak Hall Plantation did not survive the Civil War, but three outbuildings, vestiges of the formal garden created by John Townsend and Oqui Adair, remain standing more than a hundred and sixty years after they evacuated from Edisto Island. Later owners of Bleak Hall combined the property with adjacent tracts to create a larger entity called Botany Bay Plantation, encompassing more than 3,300 acres. In 1973, the three remaining outbuilding at Bleak Hall—including the Gothic-Revival “Ice House”—were added to the National Register of Historic Places. The State of South Carolina acquired this property, and in 2008 the Department of Natural Resources opened it to the public as the Botany Bay Heritage Preserve / Wildlife Management Area. Soon visitors to that beautiful preserve will learn more about the contributions of Oqui Adair.[34]

Similarly, researchers in Washington D.C. and Columbia S.C. could delve into local archives to uncover further details of Oqui’s botanical work and perhaps his personal life. He traveled halfway around the world to begin a new life and learn a new language in an unfamiliar land. He witnessed first-hand the injustice of slavery and the horrors of war before finding asylum and family comfort in the capital of South Carolina. Oqui Adair was not a hero, but his humble biography reminds us that behind every immigrant lies an interesting story.

[1] For an overview of the fair (11–25 April), see the promotion advertisement in Charleston Courier, 3 April 1855, page 3. Descriptions of Dr. Morrow’s “Japanese curiosities” appear in Charleston Courier, 19 April 1855, page 2, “A Rare Collection”; 20 April 1855, page 1, “The Institute Exhibition”; and 26 April 1855, page 2, “The Institute Fair.”

[2] Allan B. Cole, ed., A Scientist with Perry in Japan: The Journal of Dr. James Morrow (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1947), 265. On page xxii, Cole notes that Morrow’s memorial for compensation was introduced into the U.S. House of Representatives on 28 May 1856.

[3] [Washington, D.C.] Evening Star, 10 October 1859, page 3, “The Botanical Gardens.”

[4] Nell S. Graydon, Tales of Edisto (Columbia, S.C.: R. L. Bryan Company, 1955), 17.

[5] Cole, ed., A Scientist with Perry in Japan, xxii–xxiii; A. Hunter Dupree, “Science vs. the Military: Dr. James Morrow and the Perry Expedition,” Pacific Historical Review 22 (1953): 35.

[6] Graydon, Tales of Edisto, 16–17.

[7] See the letters of Mary Caroline Jenkins Townsend (1813–1889) within the Townsend Family Papers, 1850–1899, South Carolina Historical Society, 158.03.06, which form part of the larger Sosnowski Family Papers, 1840–1967, SCHS 158.00.

[8] Graydon, Tales of Edisto, 17.

[9] In a letter from January 1858, Mrs. Townsend wrote “I laughed at Oqui in Autumn about his peas, but he has managed to send in a few.” In another letter written three weeks later, Mrs. Townsend described an “amusing scene” in which Oqui complained again about the rabbits who “eat all my peas and all the carnations.” See Mrs. M. C. Townsend to her daughter, Mary Caroline, 19 January and 10 February 1858, in Townsend Papers at SCHS, 158.03.06. During the late 1850s, young Mary Caroline Townsend attended Barhamville Academy near the City of Columbia.

[10] For more information about this crop, see Richard Dwight Porcher and Sara Fick, The Story of Sea Island Cotton (Charleston, S.C.: Wyrick and Company, 2005).

[11] Graydon, Tales of Edisto, 17.

[12] Graydon, Tales of Edisto, 17.

[13] See the letters from M.C. Townsend to her daughter, Mary, 20 April 1858 and 4 June 1858, in Townsend Papers at SCHS, 158.03.06.

[14] Graydon, Tales of Edisto, 17.

[15] Pre-war letter from M.C. Townsend to her daughter, Mary, dated “October” (perhaps 1858), in Townsend Papers at SCHS, 158.03.06.

[16] Letter from M.C. Townsend to her daughter, Mary, 10 February 1858, in Townsend Papers at SCHS, 158.03.06.

[17] Note, however, that the U.S. Census enumeration of the Townsend household on Edisto Island, recorded on 3 July 1860, does not include Oqui. The Chinese-American gardener was undoubtedly present at the time, but he represented a unique anomaly within a “household” that included 272 enslaved people of African descent and six White members of the Townsend family. It appears that the census enumerator simply ignored Oqui’s presence.

[18] Graydon, Tales of Edisto, 19. Note that Charleston Courier, 25 November 1861, page 4, reported the following “Ship News”: “Steamer Cecile, [Captain] Peck, [from] Edisto. [Cargo consigned] To E. Lafitte & Co. The C[ecile]. has brought 300 steerage passengers. ¶ Steamer Beauregard, [Captain] Richardson, [from] Edisto. [Cargo consigned] To the Master. The B[eauregard]. has brough 100 steerage passengers.”

[19] A news report in Charleston Courier, 2 July 1863, page 1, “Rockville not Burnt,” states that the “enemy” had recently “contented himself with burning a small out building on the place of Hon. John Townsend. Bleak Hall was left untouched.” Graydon, Tales of Edisto, 19, states that Bleak Hall was partially destroyed by troops and freedmen during the war. William Greer, Albergotti, Abigail’s Story: Tides at the Doorstep (Spartanburg, S.C.: The Reprint Company, 1999), 342, quotes from an 1867 diary confirming that “Bleak Hall was burnt and the fine gardens and pleasure grounds are in ruins.”

[20] Charleston Courier, 29 March 1862, page 1, “Mr. Yeadon’s Festival to the Willington Rangers.”

[21] Charleston News and Courier, 5 February 1881, page 2, “Hon. John Townsend.” John Townsend’s presence in Columbia in 1862 was noted, for example, in Charleston Mercury, 28 August 1862, page 2, “Bible Society of Charleston”; Yorkville Enquirer, 29 October 1862, page 1, “Public Meeting in Columbia”; Charleston Mercury, 28 November 1862, page 1, “Legislature of South Carolina.”

[22] For an overview of the history of this institution, which opened in 1828, see Peter McCandless, “‘A House of Cure’: The Antebellum South Carolina Lunatic Asylum,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 64 (Summer 1990): 220–42.

[23] An institutional report for the year November 1848 to November 1849 says “the Green House has been paid for, and is now an ornament to our town, being well filled with rare and beautiful plants, tastefully arranged”; see South Carolina Insane Asylum, Report of the Regents of the Lunatic Asylum to the Legislature of South Carolina: November, 1849 (Columbia, S.C.: I. C. Morgan, 1850), 5. At a meeting held at the institution on 4 January 1862, the Board of Regents “Resolved That the Gardener of the Asylum be required to render to the Regents, a monthly account of sales from the Green House. Resolved That the Treasurer report the financial condition of the Institution at the next regular meeting of the Board, with a view to its future support and payment of its debts”; see South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Mental Health Commission (series S190001), Minutes of the Mental Health Commission, 1828–2006.

[24] John White, a thirty-four year-old native of Ireland, appears as a gardener in the 1860 U.S. Census of Richland County, City of Columbia.

[25] SCDAH, Mental Health Commission (series S190001), Minutes of the Mental Health Commission, 31 January 1863; 7 March 1863.

[26] SCDAH, Mental Health Commission (series S190001), Minutes of the Mental Health Commission, 31 January 1863; 4 July 1863.

[27] See the annual report of the superintendent Lunatic Asylum, dated 5 November 1864, in Charleston Courier, 20 December 1864, page 1, “The Asylum.”

[28] See Chester B. DePratter et al., “Columbia’s Two Civil War Prison Camps—Camp Asylum and Camp Sorghum,” Legacy 15 (2011): 20.

[29] Report of J. W. Parker, Superintendent and Physician of the South Carolina Lunatic Asylum, forwarded to the governor on 20 April 1868 by M. LaBorde, President of the Board of Regents of Lunatic Asylum, in Governor of South Carolina, Message No. 1 of His Excellency Gov. J. L. Orr, with Accompanying Documents (Columbia, S.C.: Phoenix Book and Job Power Press, 1868), 61; Superintendent’s Report, Lunatic Asylum, Columbia, S.C., dated 5 November 1869, in Governor of South Carolina, Message of Robert K. Scott, Governor of South Carolina, with Accompanying Documents, Submitted to the General Assembly of South Carolina, at the Regular Session, November, 1869 (Columbia, S.C.: John W. Denny, 1869), 291.

[30] The 1880 Federal Census of Richland County, City of Columbia, records the children’s names as Julia E[lla]., Oliver B[elton]., and Mary. Their mother, thirty-seven-year-old [Mary] Eliz. Adair, was born in South Carolina to parents from Holland. Within the same household was Mrs. Adair’s mother, a 72-year-old native of Holland named Christina or Christiana, but her surname is illegible.

[31] Beasley & Emerson’s Columbia Directory 1875–76, page 25: “Adair, Squire [sic], gardener, r. 14 Elmwood av.”

[32] Probate Court, Richland County, South Carolina, box 106, package 2649. Witnesses to Oqui’s will included William McBurney Sloan, Samuel Reed Stoney, and Joseph Daniel Pope. Mary Elizabeth Adair proved Oqui’s will on 25 June 1877.

[33] Columbia Daily Register, 13 June 1877, page 2, “Death of the Only Chinaman in Columbia.” Several newspapers across the state reprinted this obituary, including the Charleston News and Courier, 14 June 1877, page 4, “Death of the Only Chinaman in Columbia.”

[34] My thanks to Erin Weeks and Kaitlyn Hackathorn of SCDNR, who researched Oqui’s story for future interpretation at Botany Bay and shared their findings with me. Lish Thompson of CCPL’s South Carolina Room made invaluable contributions to our conversations about Oqui Adair and the Townsends of Bleak Hall.

NEXT: Brewing Beer for the Carolina Station during the Era of Captain George Anson

PREVIOUSLY: Oqui Adair: First Chinese Resident of South Carolina, Part 1

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments