Murder and Manhunt in 1820: Albro’s Flight from Slavery, Part 2

Processing Request

Processing Request

Following Albro’s fatal encounter with a young White man on Dewees Island, the African fled through the waters of Copahee Sound and across several mainland plantations to evade detection. Meanwhile, the victim’s father traveled to Charleston to alert public officials and initiate a manhunt. As militiamen pursued the fugitive’s trail, he was betrayed by an enslaved man who stopped him in his tracks. The true story of Albro’s flight includes plenty of drama and adventure, but it’s just one of many hundreds of similar stories of enslaved resistance in early South Carolina.

Let’s begin today’s program with a brief review of last week’s episode. Albro, formerly known as Fulliman, was a native of Africa who was brought to South Carolina at the beginning of the nineteenth century and enslaved on Long Island (now called the Isle of Palms). He fled from captivity on several occasions over the years, and was traveling with a band of fellow fugitives in the early days of 1820. After landing in a boat on Dewees Island on the night of Tuesday, February 8th, Albro was pursued by a young man named Thomas Deliesseline, whose father owned a plantation on the island. Thomas accosted the runaway and attempted to shoot him with a gun that misfired. Albro instantly retaliated with a pistol shot that ended the White man’s life.

Thomas’s father, Captain John Thompson Deliesseline, grieved for his murdered son that night, but he maintained sufficient clarity to commence efforts to track down the assailant. Another runaway captured on Dewees Island, Aaron, identified Albro as the man they wanted, but efforts to find him on the island that night proved fruitless. To initiate a broader manhunt for the murderer, Captain D. needed to speak with public officials who commanded greater resources across the plantation landscape. In short, he was obliged to travel to Charleston in person to set the wheels of justice in motion.

Wednesday, February 9th, 1820:

Following the flood tide on the morning of Wednesday, February 9th, Captain D. rowed or sailed to Charleston along the thirteen-mile inland water route from Dewees Island to Vanderhorst’s Wharf. His first stop was probably the wharf-side office of his younger brother, Francis Deliesseline, a fifty-six-year-old factor who had just won a hotly-contested election for Sheriff of Charleston District (now Charleston County). The sheriff at that time was not a law-enforcement officer, however, but rather a civil servant who executed the various decrees and sentences of both civil and criminal courts and maintained prisoners in jail until their respective trials. Although Sheriff Deliesseline lacked the legal authority to initiate a manhunt for the fugitive who murdered his nephew, he probably advised Captain D. on the steps necessary to achieve their objective.[1]

Following the flood tide on the morning of Wednesday, February 9th, Captain D. rowed or sailed to Charleston along the thirteen-mile inland water route from Dewees Island to Vanderhorst’s Wharf. His first stop was probably the wharf-side office of his younger brother, Francis Deliesseline, a fifty-six-year-old factor who had just won a hotly-contested election for Sheriff of Charleston District (now Charleston County). The sheriff at that time was not a law-enforcement officer, however, but rather a civil servant who executed the various decrees and sentences of both civil and criminal courts and maintained prisoners in jail until their respective trials. Although Sheriff Deliesseline lacked the legal authority to initiate a manhunt for the fugitive who murdered his nephew, he probably advised Captain D. on the steps necessary to achieve their objective.[1]

Unlike modern Charleston County, there was no standing body of law-enforcement officers who patrolled the countryside in 1820. Prior to the end of the American Civil War in 1865, rural law enforcement in the Lowcountry of South Carolina consisted of paramilitary slave patrols composed of armed White men who gathered periodically at night and rode on horseback through a designated “beat” near their respective homes. Dozens of mounted patrols maintained order in numerous beats across all of the Lowcountry parishes, and their authority was strengthened by laws requiring every free citizen in South Carolina to assist in the capture of enslaved runaways. The murder of Thomas Deliesseline, which resulted from his adherence to that law, now signaled the need for a greater measure of public intervention.

Sheriff Deliesseline probably accompanied his brother to see the governor of South Carolina, a forty-two year old lawyer named John Geddes, who happened to be in residence at his Charleston home on Broad Street.[2] Besides acting as the state executive and commander-in-chief, Geddes was also General of the Fourth Brigade of the South Carolina Militia, which included all of the White male citizens of Charleston District (County) between the ages of 18 and 45. After hearing Captain D.’s story of the murderous runaway, the governor issued orders to the leaders of two local militia units, Captain Payne’s company of Charleston Riflemen and Captain Toomer’s cavalry troop in Christ Church Parish (now Mount Pleasant). Each unit was ordered to mobilize a body of men as soon as possible and prepare for action.

The riflemen and horse troopers summoned by Governor Geddes, like the rest of the South Carolina’s citizens defense force, included tradesmen, shopkeepers, teachers, attorneys, merchants, and planters who participated in regular military training activities as part of their mandatory civic duties. As with members of the modern National Guard, these antebellum militiamen were required to step away from their normal lives and respond to local emergencies whenever summoned by the governor. On the 9th of February, 1820, Captains John William Payne and Anthony Vanderhorst Toomer both received instructions from Governor Geddes commanding them to scramble detachments—perhaps numbering around fifteen men each—to proceed to Dewees Island and “to apprehend, if possible, the gang of runaway Negroes.”[3]

The riflemen and horse troopers summoned by Governor Geddes, like the rest of the South Carolina’s citizens defense force, included tradesmen, shopkeepers, teachers, attorneys, merchants, and planters who participated in regular military training activities as part of their mandatory civic duties. As with members of the modern National Guard, these antebellum militiamen were required to step away from their normal lives and respond to local emergencies whenever summoned by the governor. On the 9th of February, 1820, Captains John William Payne and Anthony Vanderhorst Toomer both received instructions from Governor Geddes commanding them to scramble detachments—perhaps numbering around fifteen men each—to proceed to Dewees Island and “to apprehend, if possible, the gang of runaway Negroes.”[3]

Captain D. then proceeded to the home of Jervis Henry Stevens, a seventy-year old magistrate and musician who in 1820 held the title of Coroner of Charleston District. After describing the “tragical events” of Tuesday evening, the distressed father asked Stevens “to proceed to the spot [on Dewees Island] to investigate the circumstances of the case,” but the coroner declined to act. Mr. Stevens did not “positively refuse” to investigate the case, but instead asked the captain what he hoped to accomplish by the requested mission. Likely anticipating a future criminal trial, and perhaps advised by his brother, the sheriff, Captain D. sought to obtain from the coroner a definitive legal pronouncement of death by willful murder, as opposed to a lesser crime like accidental death or death by misadventure. Mr. Stevens was disinclined to leave his home, however, and pointed out “the impossibility of collecting a jury” for a coroner’s inquest on an island where the Deliesseline family constituted the entire White population. Furthermore, said the coroner, “the notoriety of the circumstances attending the tragical [sic] event rendered it unnecessary to summon a jury.” No one but the perpetrator witnessed the act of violence that led to the death of Thomas Deliesseline, but other men did witness the general circumstances immediately before and after his death. More importantly, the physical evidence of Tom’s wounds, as described by the grieving father, provided an indisputable and graphic illustration of the cause of death. Considering all these facts, Coroner Stevens pronounced “his opinion, that an inquest might be dispensed with.”[4]

Captain D. was dissatisfied with the response from Mr. Stevens, but he did not belabor the point with his senior colleague. Instead, he paid a visit to the City Coroner, Thomas Crafts, a twenty-eight-year-old elected official whose jurisdiction was limited to the urban confines of the Charleston peninsula. In an unrecorded conversation, Mr. Crafts agreed to impanel a coroner’s inquest on the body of Thomas Deliesseline, if the father could bring the corpse to the city as soon as possible.[5]

Having accomplished his mission in the city before sundown, Captain D. prepared to return to the scene of the crime on Dewees Island. His departure from the metropolis was likely delayed for some hours, however, by a pair of external considerations. Antebellum travelers along the coastal waterways of the South Carolina Lowcountry routinely timed their journeys to coincide with the tidal flow in the direction of their destination. It was often wiser to wait a few hours for the advantageous tide than struggle against the forces of nature. Furthermore, Captain D. might have been obliged to wait for the detachment of riflemen in order to lead their boats to his island home. Darkness came early on this winter’s evening, and the hour was late by the time the militiamen cast off from the wharves of Charleston.[6]

Thursday, February 10th, 1820:

Through Captain D.’s conversations with various friends, family, and public officials on Wednesday afternoon, word of the murder on Dewees Island spread across Charleston and found its way to the offices of the local newspapers. At sunrise on Thursday, February 10th, the morning editions of the Charleston Courier and City Gazette presented slightly different versions of what they described as the “daring” and “most horrid murder” of Thomas Deliesseline. The alleged culprit, then still at large, was identified as an enslaved fugitive named Albro, belonging to James Brandt of Long Island. Astute readers of the city’s daily newspapers might have remembered seeing Mr. Brandt’s runaway advertisements for Albro during the months preceding this fatal incident. When Thomas Deliesseline challenged the fugitive on Dewees Island, the public now learned, the enslaved man “instantly drew a pistol from his breast, heavily charged with buckshot, and discharging it into Mr. D’s face, killed him instantly upon the spot.”[7]

Through Captain D.’s conversations with various friends, family, and public officials on Wednesday afternoon, word of the murder on Dewees Island spread across Charleston and found its way to the offices of the local newspapers. At sunrise on Thursday, February 10th, the morning editions of the Charleston Courier and City Gazette presented slightly different versions of what they described as the “daring” and “most horrid murder” of Thomas Deliesseline. The alleged culprit, then still at large, was identified as an enslaved fugitive named Albro, belonging to James Brandt of Long Island. Astute readers of the city’s daily newspapers might have remembered seeing Mr. Brandt’s runaway advertisements for Albro during the months preceding this fatal incident. When Thomas Deliesseline challenged the fugitive on Dewees Island, the public now learned, the enslaved man “instantly drew a pistol from his breast, heavily charged with buckshot, and discharging it into Mr. D’s face, killed him instantly upon the spot.”[7]

Meanwhile, back on Dewees Island, the sharpshooters from the Charleston Riflemen were joined by a detachment of cavalry troopers from the mainland of Christ Church Parish. Both groups spent the daylight hours scouring the island’s forests, sand dunes, and marshes for Albro and the rest of his purported “gang of runaways,” but their efforts were fruitless. Nevertheless, the local press reported that the militiamen remained optimistic. “As the boat from which the Negroes landed at the island, had been taken possession of immediately after the murder was committed,” recalled the Charleston City Gazette, “there is reason to expect that the exertions made to apprehend them, will be successful.”[8]

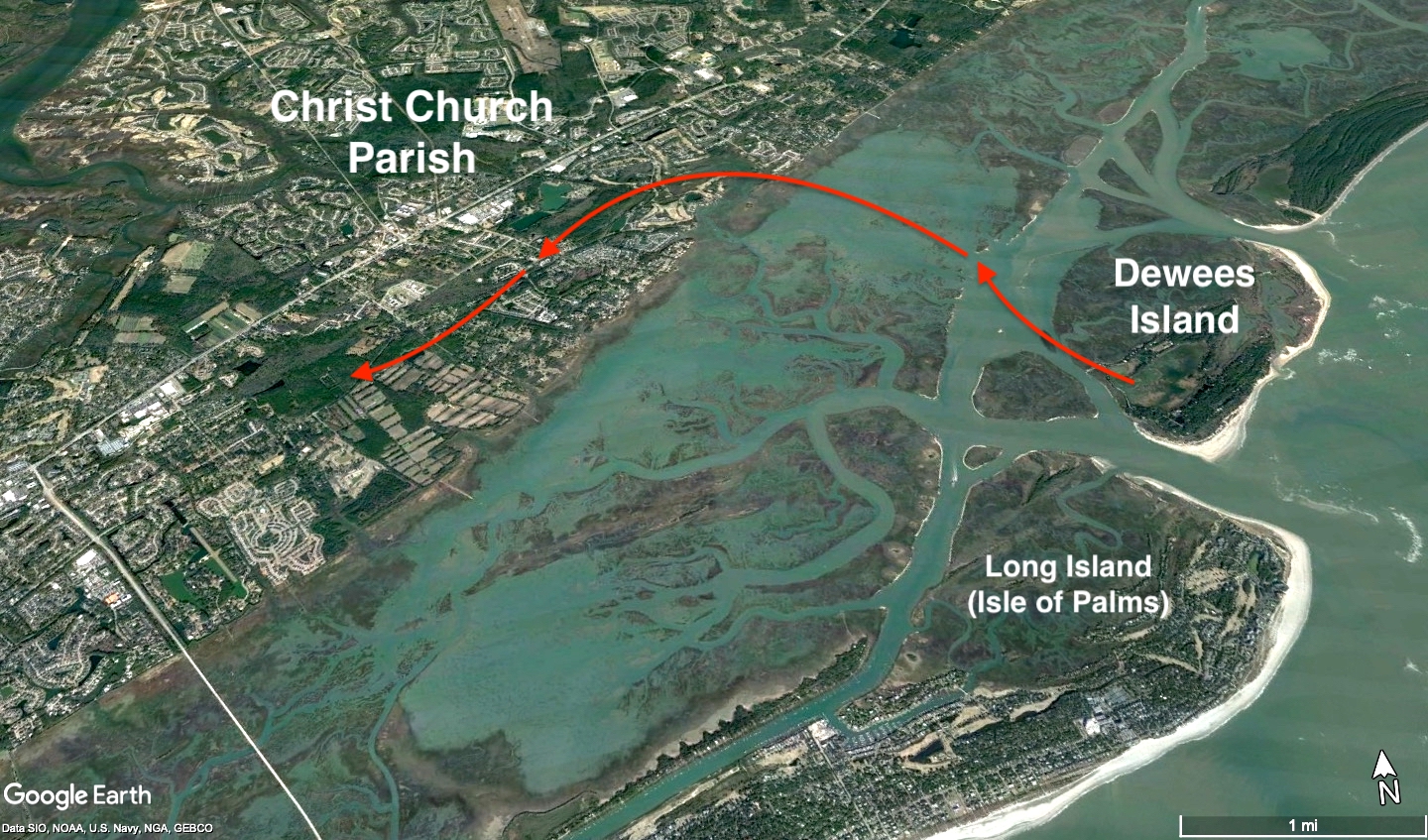

The movements of Albro’s unidentified fellow fugitives is a mystery, but the enslaved man named Aaron, captured shortly after the murder of Thomas Deliesseline, was still being held by the victim’s family on Dewees Island. Aaron knew as little of Albro’s escape route as the militiamen now combing the island, however, since he had lost sight of the alleged gunman in the darkened chaos of Tuesday evening. In reality, Albro had already slipped away from Dewees Island at some point between Wednesday morning and Thursday evening. He probably bobbed in the shallow ocean water for many hours, hiding among the salt marshes and waiting for an opportunity to swim quietly towards the mainland. The distance from the back side of Dewees Island to the adjacent shore line is nearly two miles, but the most direct path across Copahee Sound is interrupted by a maze of meandering saltwater marsh. Swimming in short bursts from one grassy mudbank to another, Albro might have conserved his energy and remained virtually invisible to passing boats.

At the conclusion of the second day of fruitless searching on Dewees Island, Captain Deliesseline, his son, John, and their enslaved servants carried Thomas’s corpse to the boat landing and prepared to cast off again for Charleston.[9] Their prisoner, Aaron, followed as well, no doubt secured in irons for the duration of their nocturnal journey. Powered by oar and sail, the party followed the flooding tide that helped propel them towards the harbor and the city’s wharves.[10]

Friday, February 11th, 1820:

Early on the morning of Friday, February 11th, the wooden launch from Dewees Island docked at one of the many wharves projecting outward from East Bay Street. One of the passengers, probably young John Deliesseline, accompanied the prisoner, Aaron, to the Charleston District Jail on Magazine Street, where he would remain in safe custody until his future trial. Captain D. likely accompanied his son’s corpse to the office of the City Coroner, the location of which is now lost.

Early on the morning of Friday, February 11th, the wooden launch from Dewees Island docked at one of the many wharves projecting outward from East Bay Street. One of the passengers, probably young John Deliesseline, accompanied the prisoner, Aaron, to the Charleston District Jail on Magazine Street, where he would remain in safe custody until his future trial. Captain D. likely accompanied his son’s corpse to the office of the City Coroner, the location of which is now lost.

As arranged nearly two days earlier, Thomas Crafts impaneled a jury of inquest composed of local citizens. Their task was to view the body of Thomas Deliesseline, to listen to the remarks of physicians examining his wounds, and hear testimony from witnesses about the circumstances of his death. The young man had expired approximately two-and-a-half days earlier, but his flesh was still sufficiently intact to distinguish the injuries that had ended his life. A newspaper description noted that the young man appeared to have “received a bullet between his nose and upper lip, which passed through the back of his head; and four buck shot [remained imbedded] in the face.” After a brief deliberation of the physical evidence and verbal testimony, the jury pronounced its verdict “that the deceased came to his death from the contents of a pistol, fired by a Negro [that is, Albro] supposed to be the property of Mr. J. W. Brandt.”[11]

Captain D. had brought his son’s body to Charleston to facilitate the coroner’s inquest, but he did not intend Tom to remain in the city permanently. The surviving weekly ledgers of burials within the corporate limits of Charleston contain no mention of Thomas Deliesseline in February of 1820. It appears, therefore, that Captain D. transported his son’s corpse back to Dewees Island for burial, or perhaps to his principal plantation homestead in the Santee River Delta. In either case, the grieving father and his remaining son, John, departed Charleston in their boat and quietly exited the scene to perform their mortuary duties in private.

While the City Coroner was occupied with his morbid business in Charleston on Friday morning, Albro was already on the mainland of Christ Church Parish. By sundown, he was lurking in the vicinity of what is now the Charleston National Golf Course. The precise itinerary of his escape route is now impossible to reconstruct, but the newspapers of February 1820 provide a few useful clues to the general direction of his movements. After nightfall on Friday, February 11th, Albro was moving in a southwesterly direction and crept onto the grounds of a large plantation owned by Dr. Anthony Vanderhorst Toomer. Dr. Toomer, who was also the captain of the cavalry troopers who had been searching for Albro on Dewees Island, owned numerous properties and resided elsewhere. At this location adjacent to Copahee Sound, he employed a White overseer to manage the plantation known for many generations by the Irish name Youghal.

Albro was probably attempting to gain access to one of the buildings on Toomer’s plantation, perhaps a store house or a slave cabin where he might find food, shelter, and friendly company. The overseer was alerted to some unusual presence, perhaps by the barking of a dog, and ventured out into the darkness to investigate. Armed with a shotgun, the overseer spied a strange dark figure in motion and fired at the interloper. Albro was wounded by a spray of small shot, but kept running until he was far from the voices shouting after him. Considering his proximity to the seashore, it’s possible that Albro returned to the water to hide his injuries and conceal his scent from pursuing dogs.[12]

Saturday, February 12th, 1820:

Albro probably kept himself hidden during the daylight hours of Saturday, February 12th, before continuing his trek in a southwesterly direction. By nightfall, he had crossed on the property of another absentee planter named James Hibben, who lived in the village of Mount Pleasant next to the ferry service that bore his name. Hibben’s Seaside plantation, as he called it, is now slightly north of Six Mile Road and is bisected by Rifle Range Road. No doubt suffering greatly from exhaustion, exposure, and hunger, Albro tried to find a friendly face who might offer help. As a local newspaper later reported, the wounded fugitive tried to “secrete himself into one of Mr. Hibben’s Negro houses,” where he might hide and recover his strength.

Albro probably kept himself hidden during the daylight hours of Saturday, February 12th, before continuing his trek in a southwesterly direction. By nightfall, he had crossed on the property of another absentee planter named James Hibben, who lived in the village of Mount Pleasant next to the ferry service that bore his name. Hibben’s Seaside plantation, as he called it, is now slightly north of Six Mile Road and is bisected by Rifle Range Road. No doubt suffering greatly from exhaustion, exposure, and hunger, Albro tried to find a friendly face who might offer help. As a local newspaper later reported, the wounded fugitive tried to “secrete himself into one of Mr. Hibben’s Negro houses,” where he might hide and recover his strength.

In contrast to the previous night, Albro’s movements did not arouse the attention of the plantation’s White overseer. Instead, the “driver,” or enslaved foreman, was alerted to the presence of a stranger among the resident Black population. Like Albro, the unidentified driver was the legal property of a White owner, but his status as the plantation’s labor foreman endowed him with a greater measure of authority than his enslaved brothers and sisters. It was his role to foster compliance among the workers and shield them from unnecessary exposure to danger. The sudden arrival of an interloper on this winter night forced the Black driver to act in a manner that illustrates the perpetual dilemma between survival and resistance under the yoke of slavery.

Albro arrived at the Hibben plantation in a pathetic state—cold, hungry, exhausted, and wounded. Any observer endowed with a modicum of empathy would have seen that he deserved some measure of charity and hospitality. Most or perhaps all of the enslaved people who witnessed Albro’s arrival that Saturday evening probably sympathized with his plight. His crime was to strive for freedom, and his zeal to escape from slavery led to a violent confrontation that resulted in the death of a man favored by the biased laws of South Carolina. In the eyes of many enslaved people, Albro might have embodied their secret dreams of resistance, and it’s possible that some tried to render aid that might help him achieve his goal.

In the eyes of the driver, however, Albro’s presence brought unwelcome danger to the enslaved community on the Hibben plantation. Anyone suspected of aiding or hiding the injured man would suffer the brutal wrath of the White authorities searching for him. The enslaved driver might have sympathized with the fugitive’s struggle for freedom, but Albro’s presence on his turf forced him to make an unpleasant decision. He had to choose between fostering resistance against the inhumanity of slavery, or enforcing the status quo and ensuring the safety of his immediate family and friends.

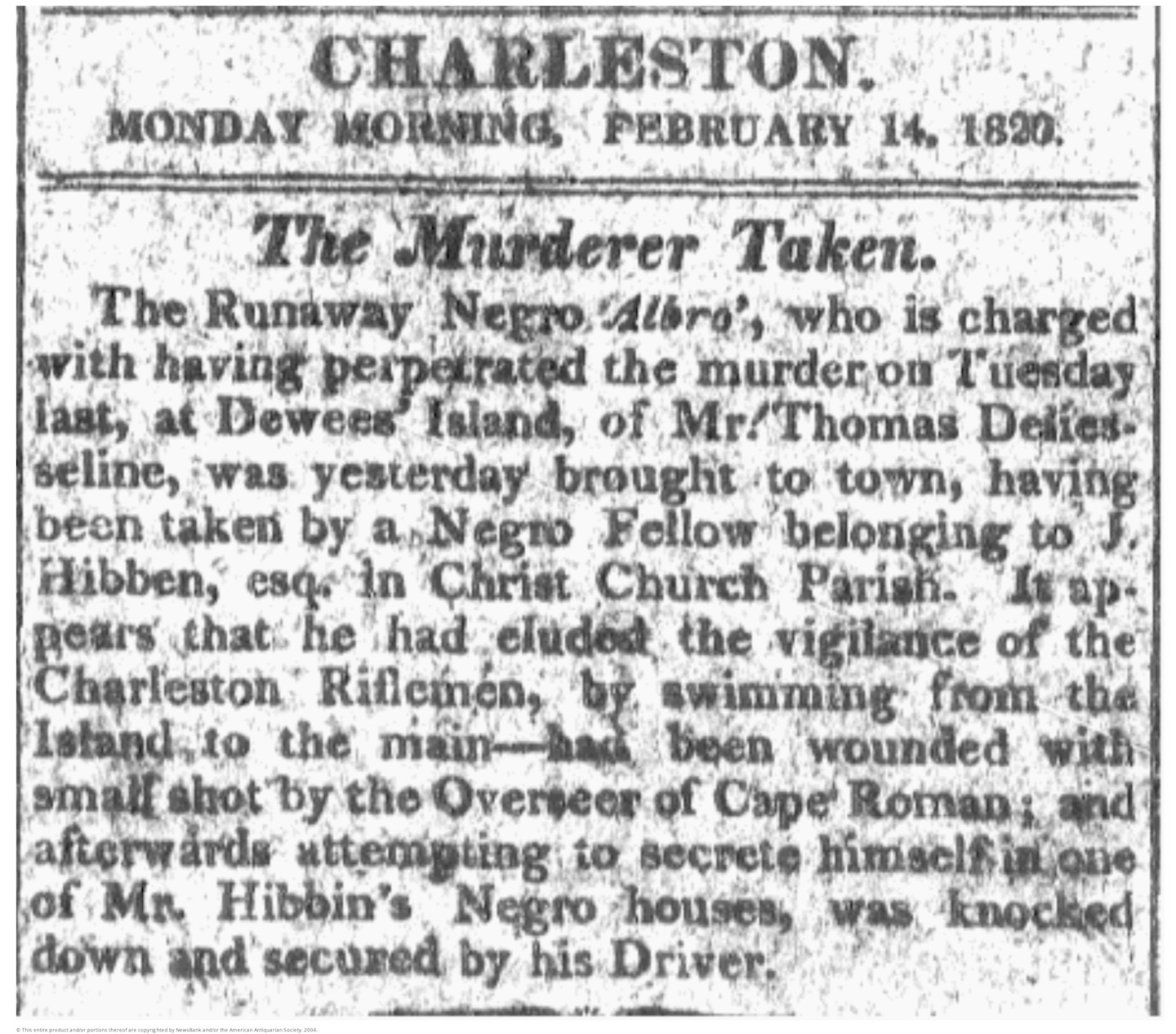

No record survives of any conversation between Albro and the driver, nor any debate among the enslaved community on Mr. Hibben’s plantation that Saturday evening. Nevertheless, it’s clear that the driver confronted the wounded fugitive and exercised his limited authority without the aid of a firearm. According to a newspaper report published after the event, Albro “was knocked down and effectually secured by his [Mr. Hibben’s] driver.” Later that evening or perhaps early the next morning, the driver delivered Albro to the plantation’s resident White overseer, who was no doubt familiar with the news of the fugitive’s recent crime.[13]

After surviving in the wild for more than four months as a runaway, and a further four days as a criminal fugitive, Albro’s flight from slavery ended in defeat. His meagre clothing was now reduced to rags, and he was exhausted after living for several days without sufficient food, water, or sleep. On the morning of Sunday, February 13th, Albro’s captors shackled his wrists and ankles with iron cuffs and lifted him into the back of a horse-drawn cart. From James Hibben’s seaside plantation, the unidentified overseer turned onto the principal road (now Highway 17) and drove the prisoner six miles southward to Mr. Hibben’s ferry landing at Haddrell’s Point in the village of Mount Pleasant.

Next week, we’ll continue with the final act of Albro’s story. During the last weeks of his life, our runaway protagonist was committed to jail in Charleston with an infamous pair of White criminals, dragged back to Mount Pleasant for a biased trial, and condemned to hang at a familiar location once known as the Red House at the forks of the road.

[1] According to Schenck and Turner, The Directory and Stranger’s Guide for the City of Charleston (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1819), Francis’s office was located at 1 Vanderhorst’s Wharf. The election of sheriff of Charleston District took place on 11–12 January 1820 and the results were tabulated on 13 January. Francis G. Deliesseline received a slightly larger number of votes than the incumbent sheriff, John Cleary, who immediately filed a legal protest. Deliesseline was declared the winner and commissioned by the governor on 4 February, but did not officially take office until the 14th of that month. See the local news printed on page two of Charleston Courier, 14 January 1820 and 5 February 1820.

[2] Schenk and Turner’s 1819 Directory and Stranger’s Guide identifies Gov. Geddes’s residence as 98 Broad Street. According to Jonathan Poston, The Buildings of Charleston (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998), 162–63, Geddes owned the properties now re-numbered as 56–58 and 60–64 Broad Street.

[3] Courier, 10 February 1920, page 2; [Charleston, S.C.] City Gazette, 11 February 1820, page 2. For more information about the militia of this era, see Michael E. Stauffer, South Carolina’s Antebellum Militia (Columbia: South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1991); and Jean Martin Flynn, The Militia in Antebellum South Carolina Society (Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Co., 1991). John William Payne was identified as the newly-elected captain of the Charleston Riflemen in City Gazette, 30 October 1817, page 2,

[4] Stevens’s response to the appeal of Captain Deliesseline was described in separate reports printed on page two of Courier, 10 February and 12 February 1820.

[5] According to James M. Crafts and William F. Crafts, The Crafts Family. A Genealogical and Biographical History of the Descendants of Griffin and Alice Craft, of Roxbury, Mass. 1630–1890 (Northampton, Mass.: Gazette Printing Company, 1983), 189, Thomas Crafts of Charleston was born in December 1791 and died in December 1821.

[6] According to Courier, 11 February 1820, page 2, the riflemen “left town late on Wednesday night.”

[7] The evening paper, [Charleston, S.C.] Southern Patriot, 10 February 1820, page 2, copied the Courier’s text of the same day. Copies of the Charleston Times, also an evening paper, do not survive from this era. The quotation appears in Courier, 10 February 1820, page 2.

[8] The “party of 10 or 12 persons (from the main)” who were “scouring Dewees’ Island, on Thursday,” as mentioned in City Gazette, 12 February 1820, page 2, were liked members of “Captain Toomer’s Troop of Cavalry from Christ Church Parish” mentioned in City Gazette, 11 February 1820, page 2, as having been “ordered to the spot.”

[9] City Gazette, 12 February 1820, page 2.

[10] City Gazette, 12 February 1820, page 2, mentioned the departure of a boat carrying Thomas’s corpse on “Thursday evening.”

[11] City Gazette, 12 February 1820, page 2; The description of the wound appears in City Gazette, 10 February 1820, page 2.

[12] Albro’s encounter with the overseer at the plantation of Captain Toomer was described in both Courier, 14 February 1820, page 3, and Southern Patriot, 14 February 1820, page 2. The City Gazette, 14 February 1820, page 2, reported that Albro “was wounded with small shot,” but inaccurately stated that he was wounded “by the overseer of Cape Roman.” For more information about Toomer and his plantation, see See Michael Trinkley, et al., Youghal: Examination of an Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Plantation, Christ Church Parish, Charleston County, South Carolina, Chicora Foundation Research Series 65 (Columbia, S.C.: Chicora Foundation, 2006), 17–19.

[13] Albro’s capture is described in City Gazette, 14 February 1820, page 2; Courier, 14 February 1820, page 3; Southern Patriot, 14 February 1820, page 2. James Hibben’s Seaside or Sea Side plantation (distinct from a nearby plantation of the same name belonging to the Barksdale family) is described in Natalie Adams Pope, Phase I Archaeological Survey of the Rifle Range Road Tract, Charleston County, South Carolina (New South Associates Technical Report 2235, September 2013).

NEXT: Murder and Manhunt in 1820: Albro’s Flight from Slavery, Part 3

PREVIOUSLY: Murder and Manhunt in 1820: Albro’s Flight from Slavery, Part 1

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments