Murder and Manhunt in 1820: Albro’s Flight from Slavery, Part 1

Processing Request

Processing Request

When an enslaved African man named Albro asserted his freedom and fled from the Isle of Palms in 1819, the laws of South Carolina marked him as a criminal fugitive. Spied and then pursued by white men on Dewees Island one night in early 1820, Albro resisted their efforts to capture him and killed one of his assailants. The dramatic story of his flight and the ensuing manhunt and trial, recorded in a series of brief newspaper reports, illuminates a broader cycle of resistance and retribution that forms a large part of Lowcountry history.

I stumbled into today’s story while searching through the newspapers of early South Carolina for information related to the history of Dewees Island.[1] It’s worth mentioning that I first encountered this narrative in reverse order; that is, I first read about Albro’s execution, then moved backwards to learn about his trial and crime. Here I recognized this material as the sort of murder-mystery story that captivates the imagination of many adults through dramatized novels and screenplays. After searching for and finding further evidence, I realized that the antagonist in this story, Albro, was an enslaved fugitive struggling to gain his freedom. As I mentioned in last week’s program, many thousands of enslaved South Carolinians tried to run away from slavery in the generations before 1865. In contrast to most of those individuals, however, the paper trail covering Albro’s life provides sufficient detail to reconstruct a reasonable outline of a story that exposes the dangers inherent to that path of resistance.

Then I paused to think about the most appropriate manner of telling the story. This is not just another cookie-cutter story about crime and punishment, nor is it simply a tale of inter-racial violence in antebellum South Carolina. From the distance of two centuries, we can see two sides of this story. In the eyes of early nineteenth century White South Carolinians, most of whom viewed slavery as a natural and positive institution, Albro was a criminal slave who was justly executed for the crime of murder. By viewing the evidence through the lens of twenty-first century hindsight, however, we see a more complicated scenario. Albro was not a faceless drone who transgressed the legal bounds of slavery, but a real person struggling to escape a life of captivity, whose zeal for freedom clashed violently against an equal force of discrimination and suppression.

Who Was Albro?

We don’t know precisely when Albro arrived in South Carolina, and we don’t know any details of his origins in Africa. An 1819 advertisement stated that his African name was “Fulliman,” but we have to recognize that this name might represent an Anglicized corruption of the name he spoke aloud in his native language on his arrival in Charleston. Perhaps he identified himself as a member of the populous Fula people of West Africa, the vast majority of whom practice the Islamic faith, and perhaps he further identified himself as an imam or spiritual leader within his community. We will never know the correct spelling of Fulliman’s name, but the point to remember is that he arrived here with an African identity that was supplanted by the Americans who denied his freedom in South Carolina.

We don’t know precisely when Albro arrived in South Carolina, and we don’t know any details of his origins in Africa. An 1819 advertisement stated that his African name was “Fulliman,” but we have to recognize that this name might represent an Anglicized corruption of the name he spoke aloud in his native language on his arrival in Charleston. Perhaps he identified himself as a member of the populous Fula people of West Africa, the vast majority of whom practice the Islamic faith, and perhaps he further identified himself as an imam or spiritual leader within his community. We will never know the correct spelling of Fulliman’s name, but the point to remember is that he arrived here with an African identity that was supplanted by the Americans who denied his freedom in South Carolina.

Nothing is known about Fulliman’s age or the chronology of his arrival in South Carolina. Based on reports of his physical traits in several newspaper notices, I suspect that he was born sometime between 1780 and 1790. He probably entered the port of Charleston aboard a slave ship that arrived here sometime after January 1st, 1804, when South Carolina re-opened the trans-Atlantic slave trade directly from West Africa, but before January 1st, 1808, the date on which Federal law prohibited the further importation of African captives into the United States (see Episode No. 50). If Fulliman arrived during the last twenty-two months of that legal traffic in human captives, he would have stepped ashore at Gadsden’s Wharf, now the site of Charleston’s International African American Museum.

The paper trail tracing Fulliman’s legal transition from free African to enslaved South Carolinian is now lost, but we can pinpoint his location and condition by the summer of 1813. At that time, he was the legal property of James Washington Brandt (ca. 1777–1827), a native of New York who had settled in the Lowcountry of South Carolina around the turn of the nineteenth century. Through a series of transactions that are now difficult to trace, Mr. Brandt acquired part of Long Island (now called the Isle of Palms), a narrow strip of sand and maritime forest facing the Atlantic Ocean to the east and the mainland of Christ Church Parish to the west. On this isolated sea island, located less than nine miles as the crow files from urban Charleston, James Brandt used enslaved laborers to work the soil for his profit.[2]

Like most other African captives who were brought to this country in chains, Fulliman’s first owner or owners assigned him a new name that was more familiar to their Anglo-American experience. James Brandt identified Fulliman by the name name “Albro,” which is a shortened version of the name Aldborough, an ancient village in Yorkshire in the northeast of England. This name might seem unusual to modern audiences, but it would not have seemed so to the Anglo-Americans of early South Carolina. The application of European place names to enslaved men was a common practice during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (see Episode No. 175), and local popularity of the name Aldborough increased after the British warship HMS Aldborough (sometimes spelled Alborough or Albro) was twice stationed in Charleston harbor, between 1728 and 1734, and again between 1745 and 1749.

Few personal details about Albro’s life survive. We don’t know who he left behind in Africa, for example, or whether any members of his native family travelled with him across the Atlantic Ocean. At the plantation of James Brandt on Long Island, Albro lived for at least a decade among a small community of enslaved people of African descent, but Brandt left behind no records that illuminate the size or composition of that group. Nor do we know whether Albro formed a family relationship with anyone during his years of residence on the coast of South Carolina. For anyone wishing to transform his story into a made-for-tv movie, therefore, you’ll have to invent some sort of romantic interest out of your imagination.

Long Island, like other neighboring sea islands, is surrounded by sea waters that ebb and flow with the daily tides, but planters like James Brandt did not consider the open water to be a sufficient defense against efforts to escape. Animals herded onto small barrier islands in this area, such as Hog Island, Goat Island, and Horse Island, rarely ventured into the water, but enslaved human motived by dreams of freedom sometimes did. As on mainland plantations across South Carolina and in neighboring states, the owners of sea island plantations maintained a culture of coercion and intimidation to discourage such dreams. Unauthorized movements beyond prescribed boundaries were routinely checked by various forms of punishment designed to deter future transgressions. As the story of Albro proves, however, such efforts were not always successful.

Escape from Long Island:

On the sultry night of August 17th in the year 1813, Albro climbed into a small wooden boat with five other enslaved people and rowed or sailed away from Long Island. Immediately after their illegal departure, James Brandt sent descriptions of the runaways to the local press in Charleston. Newspaper advertisements first published on August 19th provide our first glimpse of the African fugitive. The text described Albro as standing about five feet two inches tall, “with a broad foot, [and] has his country marks on his breast.” The “country marks” mentioned here refer to the sort of ritual scarification practiced by many of the cultural groups indigenous to West Africa. In their eyes, such permanent markings are badges of achievement, maturity, and family identity meant to be celebrated and admired. To conceal his country marks in South Carolina in 1813, however, Albro covered his body with a striped, coarse cotton shirt, lightweight, ankle-length canvas “duck trowsers,” and a canvas “tarpaulin hat” (soaked in tar or wax to make it waterproof).

On the sultry night of August 17th in the year 1813, Albro climbed into a small wooden boat with five other enslaved people and rowed or sailed away from Long Island. Immediately after their illegal departure, James Brandt sent descriptions of the runaways to the local press in Charleston. Newspaper advertisements first published on August 19th provide our first glimpse of the African fugitive. The text described Albro as standing about five feet two inches tall, “with a broad foot, [and] has his country marks on his breast.” The “country marks” mentioned here refer to the sort of ritual scarification practiced by many of the cultural groups indigenous to West Africa. In their eyes, such permanent markings are badges of achievement, maturity, and family identity meant to be celebrated and admired. To conceal his country marks in South Carolina in 1813, however, Albro covered his body with a striped, coarse cotton shirt, lightweight, ankle-length canvas “duck trowsers,” and a canvas “tarpaulin hat” (soaked in tar or wax to make it waterproof).

Brandt’s runaway notice stated that Albro fled in company with a forty-year old enslaved man named Hercules, a sixteen-year-old youth named Charles, an enslaved mulatto woman named Ellen and her two-year-old son, and an African native named George who belonged to the owner of a neighboring plantation. According to Brandt’s advertisement, Ellen had entered his house just before their nocturnal exodus and stolen a significant quantity of fine clothing, jewelry, and at least $138 in cash. The group then “escaped in a boat” under the cover of darkness and disappeared among the expansive marshlands that blanket the coastline. Brandt offered a reward of $25 to any citizen for the capture and return of all six people, “and all the cash that may be found on them.”[3]

No details survive of the group’s itinerary during the autumn of 1813, nor the duration of their adventure, but their efforts to regain their freedom were only temporarily successful. Later records indicate that Albro, the mulatto woman Ellen, and her son, Horatio, eventually returned to the custody of James Brandt, but the fate of Hercules, Charles, and George is unknown.[4]

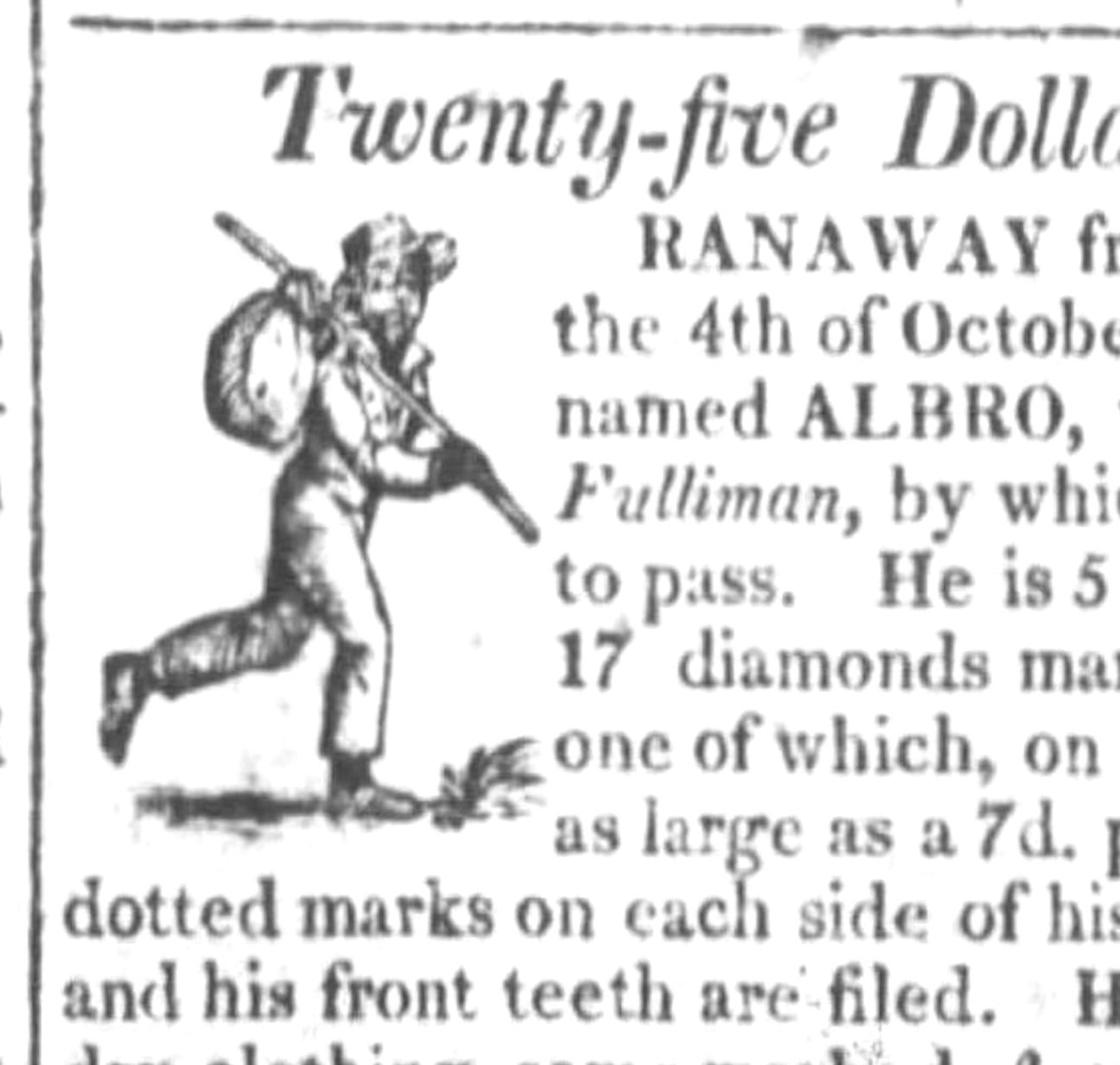

Six years after his initial escape from Long Island, Albro ran away again on October 4th, 1819, although not in company with anyone else from James Brandt’s plantation. Rather than publish an immediate notice of his disappearance, Brandt waited several weeks for the enslaved African to return on his own. This purposeful delay, which was described by many other slave owners in unrelated runaway notices, suggests that Albro might have temporarily absented himself from Long Island on several occasions since 1813, and that Brandt was sufficiently familiar with the enslaved man’s temperament to wait for his eventual return. Two months after Albro’s latest flight, however, Brandt finally composed the text of a runaway advertisement and sent it to Charleston for distribution. The published notice appeared in each of the city’s four daily newspapers from the last day of November 1819 to the beginning of February 1820.

Six years after his initial escape from Long Island, Albro ran away again on October 4th, 1819, although not in company with anyone else from James Brandt’s plantation. Rather than publish an immediate notice of his disappearance, Brandt waited several weeks for the enslaved African to return on his own. This purposeful delay, which was described by many other slave owners in unrelated runaway notices, suggests that Albro might have temporarily absented himself from Long Island on several occasions since 1813, and that Brandt was sufficiently familiar with the enslaved man’s temperament to wait for his eventual return. Two months after Albro’s latest flight, however, Brandt finally composed the text of a runaway advertisement and sent it to Charleston for distribution. The published notice appeared in each of the city’s four daily newspapers from the last day of November 1819 to the beginning of February 1820.

The advertisement identified the runaway as Albro, but noted that his “African name is Fulliman, by which he may have the art [that is, ingenuity] to pass.” Brandt described the enslaved man as standing “5 feet 4 inches high,” and then proceeded to document the physical marks of Fulliman’s African youth. He “has 17 diamonds marked on his breast,” said Brandt, “in one of which, on the left side, is a scar as large as a 7d. [seven-penny] piece.” This round scar, distinct from the incised diamond shapes, might have resulted from a wound inflicted during Albro’s previous runaway experience. Recalling the man’s facial features, James Brandt stated that Albro “has also two dotted marks on each side of his face, near his temples,” which might indicate further scarification or perhaps tattoos. “His front teeth are filed,” said Brandt, referring to a sharpening modification favored by many of the African peoples brought to the Americas. Finally, the owner noted that Albro had taken “sundry clothing” when he ran away, “some marked A, and others Albro.” It seems likely that he packed additional layers of clothing, anticipating the onset of cold weather during the approaching winter season. James Brandt offered a reward of twenty-five dollars “on his delivery to the subscriber, or the Master of the Work-house [on Magazine Street in Charleston], and double that amount on proof to conviction of his being harbored or employed by any person whatever.”[5]

Albro probably fled from Long Island in a boat during his 1819 escape, although Mr. Brandt did not specify the manner of his exodus. While the African native later demonstrated sufficient physical stamina to swim between islands and the mainland, I suspect that Albro remained dry and followed a different route on the night of October 4th. Later newspaper reports identify him as one member of a party or “gang” of enslaved fugitives who maintained their freedom by traversing the coastal waterways in a wooden boat. If this band of runaways had procured a boat prior to Albro’s flight, they might have rowed or sailed to Long Island on previous nights in search of food, clothing, and companionship among the enslaved community on Mr. Brandt's plantation. In this hypothetical scenario, Albro might have seized the opportunity to escape, or arranged to depart with the floating maroons during a future nocturnal visit.

Albro probably fled from Long Island in a boat during his 1819 escape, although Mr. Brandt did not specify the manner of his exodus. While the African native later demonstrated sufficient physical stamina to swim between islands and the mainland, I suspect that Albro remained dry and followed a different route on the night of October 4th. Later newspaper reports identify him as one member of a party or “gang” of enslaved fugitives who maintained their freedom by traversing the coastal waterways in a wooden boat. If this band of runaways had procured a boat prior to Albro’s flight, they might have rowed or sailed to Long Island on previous nights in search of food, clothing, and companionship among the enslaved community on Mr. Brandt's plantation. In this hypothetical scenario, Albro might have seized the opportunity to escape, or arranged to depart with the floating maroons during a future nocturnal visit.

The number and identity of Albro’s fellow fugitives is unknown, but the party must have included at least three or four men. Besides Albro, only one other name survives: an enslaved man named Aaron, who belonged to another planter in Christ Church Parish named Moses Whitesides (1794–1852). I haven’t yet found any description Aaron’s physical appearance, but he was present on the estate inventory of Mr. Whitesides’s father in 1810 and might have been around the same age as Albro.[6]

Albro and his new band of runaways apparently lived in seclusion for several months, probably moving at night between the various sea islands and among the expansive marshlands now forming part of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway. On occasion, they likely ventured onto the mainland in secluded spots between the village of Mount Pleasant and Awendaw, searching for supplies and friendly faces. Local waters provided the fugitives with a bounty of fish, crab, and shrimp, and they might have bartered in secret with the enslaved people of mainland plantations for rice, corn, beans, and eggs. By clandestine theft or perhaps through illicit trading, Albro and Aaron also acquired pistols, gunpowder, and ammunition, with which they no doubt intended to defend their new-found freedom.

The Clash on Dewees Island:

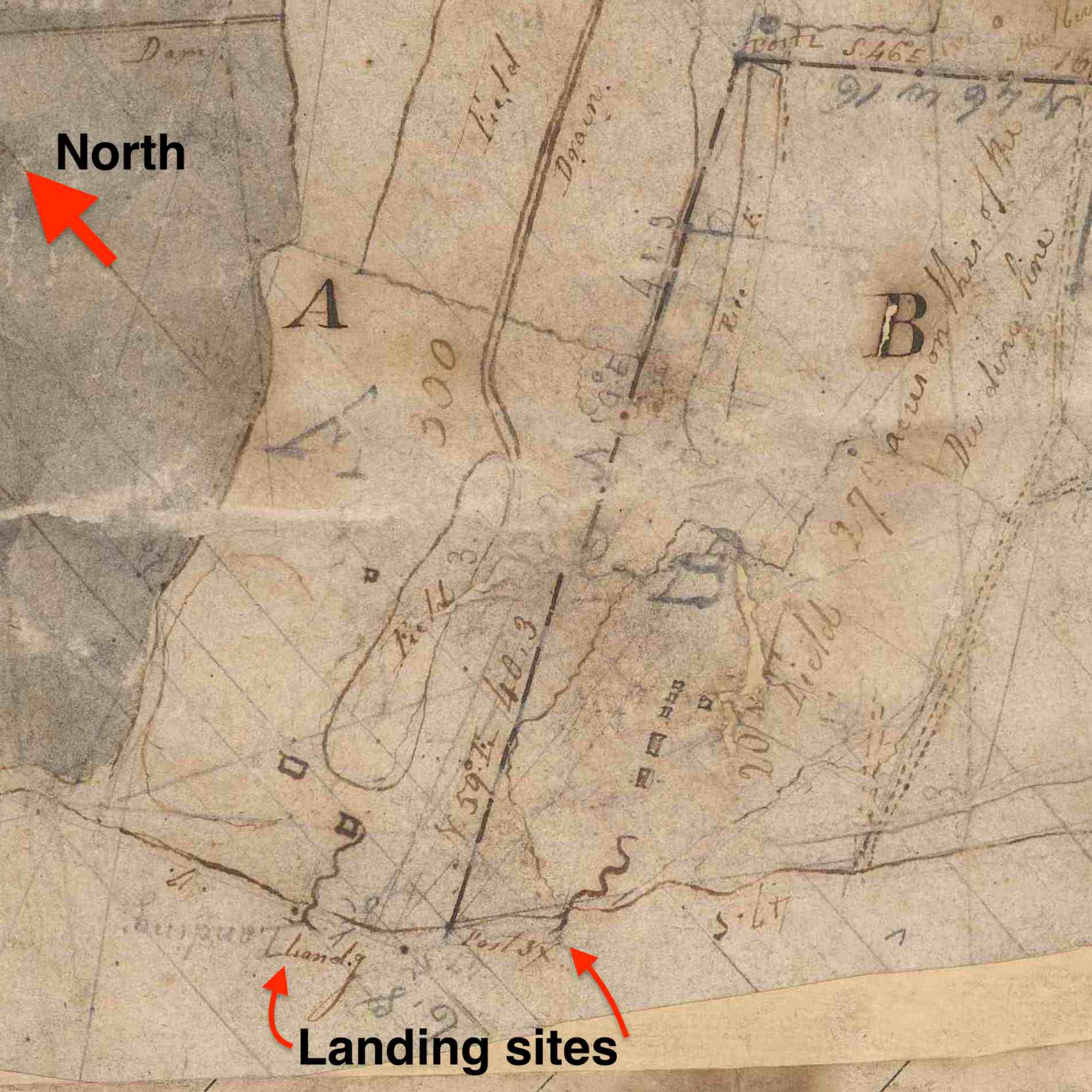

Just after sunset on the evening of Tuesday, February 8th, 1820, Albro and his compatriots rowed or sailed their boat across the inlet that separated Long Island from its northern neighbor. Ahead lay the southeastern shore of Dewees Island, a disc-shaped sea island covered with sand dunes, maritime forests, and impenetrable salt marshes. A small wooden wharf then stood near the location of the island’s present boat landing, but it’s unclear whether Albro’s team made use of the wharf or landed among the expanse of tall marsh grass nearby. Once on land, the fugitives could see the silhouette of a large house immediately to the north, with chimneys billowing smoke from winter fires within. To the east, beyond a stretch of cleared fields, stood a row of modest cabins that sheltered a small community of enslaved people. Albro, Aaron, and the others crept through the darkness towards the cabins, perhaps following a route they had used on previous nocturnal visits to trade and commune with the island’s Black population.

Just after sunset on the evening of Tuesday, February 8th, 1820, Albro and his compatriots rowed or sailed their boat across the inlet that separated Long Island from its northern neighbor. Ahead lay the southeastern shore of Dewees Island, a disc-shaped sea island covered with sand dunes, maritime forests, and impenetrable salt marshes. A small wooden wharf then stood near the location of the island’s present boat landing, but it’s unclear whether Albro’s team made use of the wharf or landed among the expanse of tall marsh grass nearby. Once on land, the fugitives could see the silhouette of a large house immediately to the north, with chimneys billowing smoke from winter fires within. To the east, beyond a stretch of cleared fields, stood a row of modest cabins that sheltered a small community of enslaved people. Albro, Aaron, and the others crept through the darkness towards the cabins, perhaps following a route they had used on previous nocturnal visits to trade and commune with the island’s Black population.

Meanwhile, inside the big house, at least four adult White men were settling in for a routine winter’s evening. The master of the house was Captain John Thompson Deliesseline (1753–1820), a sixty-six year-old widower and veteran of the American Revolution.[7] Captain D., as we might call him, apparently spent more time at another plantation in the parish of St. James, Santee, while his eldest son, Thomas, aged around 25 years, reportedly worked as a gunsmith in Charleston. The captain’s younger son, John, was then 23 years of age, and might have spent more time on the island than his father and brother.[8] On this February evening, however, the father and his two sons had gathered on Dewees Island with a visitor known only as Mr. Laval, a Frenchman who might have been related to other well-known men of the same name who lived in Charleston.[9] Amidst their conversation, perhaps after enjoying their evening meal, some noise or movement caught the attention of John Deliesseline, who moved to a nearby window to peer into the darkness.[10]

The events that unfolded next were described in several local newspapers later in the week. Because those published reports contain several small but important discrepancies, it’s now difficult to reconstruct the precise sequence of events with iron-clad confidence. The following narrative, therefore, reflects my best efforts to interpret the evidence and determine the most logical chain of actions and reactions.

By 7 p.m. on this winter’s evening, the sun had disappeared below the horizon and the waning crescent moon reflected a modest glow across the shoreline of Dewees Island. John Deliesseline, perhaps standing at a south-facing window, called to his father. He reported seeing a boat, “full of Negroes,” land on the nearby shore. These interlopers were not members of the resident enslaved population, so the White men concluded that they must be runaways from a nearby plantation. John then proposed to his older brother, Thomas, and Mr. Laval, “that they should go in pursuit of them,” in conformity to their civic duty as free White citizens of this slave-holding community.[11] The three men immediately began to prepare for what they undoubtedly expected to be an unpleasant and dangerous confrontation. They loaded their guns—probably muskets but perhaps also pistols—and dressed for the chilly weather outside. They exited the house and tread stealthily across the property towards the scene of the boat landing.

At an unknown location on the darkened landscape, the three White men crept close the party of Black fugitives, who were apparently distracted and did not notice their approach. John Deliesseline, the youngest of the trackers, then lunged forward and seized one of the maroons. During the ensuing struggle, the man’s coat tore away as he fought to escape from John’s firm grip. Albro, Aaron, and the other startled fugitives scampered from the scene in different directions, while John raised his musket and fired at the coatless man. The spark from his flintlock gun failed to ignite the powder, however, and the dark-skinned maroons continued their flight.

At this point, the three White men appear to have separated and pursued targets in different directions. Thomas Deliesseline soon caught up with one of the strangers, whom we know as Albro, and grabbed hold of the back of his coat. A physical struggle ensued, each man committed to protecting the values he held dear. Albro fought to escape with his life and preserve his freedom, while Thomas sought to enforce the law of White supremacy over a fugitive stranger. The Black man’s coat peeled away from his body as he writhed under Tom’s grip, and the White youth stepped back to ready his gun. With a musket barrel pointed at his breast, Albro reached into his buttoned waistcoat and pulled out a loaded pistol. Tom pulled the trigger to fire his gun, but the powder failed to ignite. Hearing the impotent click of his attacker’s flint, Albro made a split-second decision that instantly changed the course of his life. He squeezed the trigger of his extended pistol and fired a blast of lead and smoke towards the darkened figure in front of him. Tom’s body crumpled instantly and fell, lifeless, to the ground.

Through the acrid smoke, Albro turned and ran as fast as he could. He was free for the moment, but he must have realized that his life would never be the same. He had lived as a fugitive from slavery for the past four months and four days, but now he was a murderer whose days were surely numbered. The path of Albro’s escape on the night of February 8th, 1820 is unclear, but he was apparently determined to get as far away from Dewees Island as possible. He probably ran in a northwesterly direction, through the maritime forest on the backside of the island and into the salt marsh surrounding Horse Pen Creek. After wading into the cold seawater, he traversed acres of marsh to Bullyard Sound. With the echo of voices shouting after him in the darkness, Albro slipped into the open water and swam towards the mainland.

Through the acrid smoke, Albro turned and ran as fast as he could. He was free for the moment, but he must have realized that his life would never be the same. He had lived as a fugitive from slavery for the past four months and four days, but now he was a murderer whose days were surely numbered. The path of Albro’s escape on the night of February 8th, 1820 is unclear, but he was apparently determined to get as far away from Dewees Island as possible. He probably ran in a northwesterly direction, through the maritime forest on the backside of the island and into the salt marsh surrounding Horse Pen Creek. After wading into the cold seawater, he traversed acres of marsh to Bullyard Sound. With the echo of voices shouting after him in the darkness, Albro slipped into the open water and swam towards the mainland.

Meanwhile, John Deliesseline and Mr. Laval had both failed to capture any of the enslaved fugitives, and retraced their steps to rejoin Thomas. Following the trail of his pursuit, the men found him alone, lying in a heap next to his gun. With the aid of a lantern or torch, John turned his brother’s body to search for signs of life. Instead of a youthful visage, he found a bloody mess. The lead shot from Albro’s pistol had deformed Tom’s face and pierced a hole in the back of his skull. Thomas Deliesseline had died instantly from a wound received while trying to arrest a stranger, but no one except the perpetrator had witnessed the violent act.

John or perhaps Mr. Laval ran back to the house to inform Captain D. of the calamitous events. The father was agonized by the news of Tom’s death, but he acted swiftly to catch he culprit. Turning to the enslaved people who formed the majority of the small island’s population, the captain distributed firearms and other weapons and ordered them out into the darkness to search for the scattered fugitives. At some point during the night, one of the enslaved “fellows” owned by the Deliesseline family managed to coax one of the maroons into custody, “by address and good management,” and brought him to the captain’s residence.

Under interrogation by Captain D. and his son, the prisoner identified himself as Aaron, who came from a plantation in Christ Church Parish owned by Moses Whitesides. Although he was carrying a pistol loaded with “a bullet and 5 buck shot” at the time of his arrest, Aaron steadfastly denied shooting anyone that evening. He identified the culprit as an African named Albro, who belonged to Mr. Brandt of Long Island, though it’s not clear how Aaron knew which of his colleagues had fired the fatal shot.

Despite a vigorous search across Dewees Island through the night and into the following morning, Aaron’s fellow fugitives were still at large. Their boat remained where it had landed the previous evening, which led the inhabitants to suspect that the maroons were still lurking somewhere on the island. It was also possible, they imagined, that the enslaved runaways might have swum to one of the nearby islands or to the mainland. At sunrise on February 9th, Captain Deliesseline determined that it was time to raise the alarm among his neighbors and across the broader plantation landscape. With his son John and their guest, Mr. Laval, the captain departed from his island refuge in a boat for Charleston to report Albro’s crime and mobilize a manhunt to track down the fugitive suspects.[12]

Despite a vigorous search across Dewees Island through the night and into the following morning, Aaron’s fellow fugitives were still at large. Their boat remained where it had landed the previous evening, which led the inhabitants to suspect that the maroons were still lurking somewhere on the island. It was also possible, they imagined, that the enslaved runaways might have swum to one of the nearby islands or to the mainland. At sunrise on February 9th, Captain Deliesseline determined that it was time to raise the alarm among his neighbors and across the broader plantation landscape. With his son John and their guest, Mr. Laval, the captain departed from his island refuge in a boat for Charleston to report Albro’s crime and mobilize a manhunt to track down the fugitive suspects.[12]

Join me next week for the continuation of this dramatic story. Despite his efforts to elude capture, Albro was wounded and eventually battered into submission. The details of his flight, arrest, and trial illuminate the hardships faced by scores of other enslaved fugitives in antebellum South Carolina who were caught in the snares of legal system designed to suppress their civil rights.

[1] I was pleased to discover, later, that Suzannah Smith Miles briefly described Albro’s story in The Islands: Sullivan’s Island and Isle of Palms, An Illustrated History (by the author, 2013), 47–49.

[2] According to the “Return of Deaths within the City of Charleston” for the week of 9–16 September 1827, held within CCPL’s archive, James Washington Brandt was a fifty-year-old native of New York who died of “debility” in Charleston on 12 September 1827 and was buried in the “country.”

[3] See Brandt’s advertisement printed in [Charleston, S.C.] City Gazette, 19 August 1813, page 3, and in subsequent issues.

[4] James W. Brandt sold the mulatto woman named Ellen and her son, Horatio, to Thomas Fuller on 3 June 1818. See South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Miscellaneous Records (Main Series), Bills of Sale, 4P: 203.

[5] See Brandt’s notice in Charleston Courier, 30 November 1819, page 3, bottom of the first column, and many subsequent issues.

[6] An enslaved man named Aaron appears in the 1810 inventory of the property of Moses Whitesides senior, residing on a plantation in Christ Church Parish, separate from Whitesides’s “Village House” in Mount Pleasant. See the inventory of Whitesides’ estate, dated 30 May 1810, in SCDAH, Inventories and Appraisement Books, Book E (1802–19), page 11.

[7] John Thompson Deliesseline (1753–1820) was the captain of a company of militia under Colonel Hugh Giles (1750–1802), Lower Craven County Regiment, during the American Revolution, August 1780–August 1782. SCDAH, Accounts Audited of Claims Growing out of the Revolution, File No. 1877A.

[8] Thomas’s age and occupation were mentioned in City Gazette, 10 February 1820, page 2, “Murder!!” John Deliesseline’s age is derived from the dates on his tombstone (31 October 1786–14 January 1840) in the churchyard of Christ Church Parish in Mount Pleasant.

[9] Both Louis Laval (died 1839) and William Laval (1788–1865) were candidates for Sheriff of Charleston District in 1819. William’s father, Colonel Jacint Laval (1762–1822), served under Rochambeau at Yorktown during the American Revolution and was a U.S. Army officer during the War of 1812.

[10] At the time of this story in 1820, the Deliesseline family owned 279 acres of oceanfront land on Dewees Island, while Theodore Samuel Marion owned the remaining 300 acres of high land (exclusive of marsh) and resided at Medway Plantation in the parish of St. James, Goose Creek. The sparse and incomplete paper trail of the island’s ownership during the early decades of the nineteenth century suggests that the island probably hosted just one working plantation, the profits of which were divided between two family interests. An 1804 plat of the island, created to record a partition of the property into two halves, appears to show one boat landing, one large residence, one row of slave cabins, and one system of fields, all divided by an apparently imaginary line drawn through the landscape. See Charleston Country Register of Deeds, Plat Collection of John McCrady, Plat No. 6185.

[11] See section 25 of Act No. 670, “An Act for the better Ordering and Governing Negroes and other Slaves in this Province, ratified on 10 May 1740, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, Volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 397–417.

[12] My reconstructed narrative represents an amalgam of the descriptions published in Charleston Courier, 10 February 1820, page 2, “Daring Murder,” and [Charleston, S.C.] City Gazette, 10 February 1820, page 2, “Murder!!”

NEXT: Murder and Manhunt in 1820: Albro’s Flight from Slavery, Part 2

PREVIOUSLY: Escaping Slavery: Resistance on the Run

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments