The Mermaid and the Hornet in the Hurricane of 1752

Processing Request

Processing Request

The powerful hurricane of mid-September 1752 destroyed nearly every watercraft in the vicinity of Charleston, with two dramatic exceptions. His Majesty’s warship Mermaid was driven ashore near the Wando River, while HMS Hornet nearly capsized in the harbor. Descriptions of these harrowing events, written by the officers of both ships, have gathered dust in London archives for nearly three centuries. In this episode of Charleston Time Machine, we’ll explore their forgotten eye-witness accounts of the deadly cyclone and the herculean efforts required to get their vessels back in ship-shape.

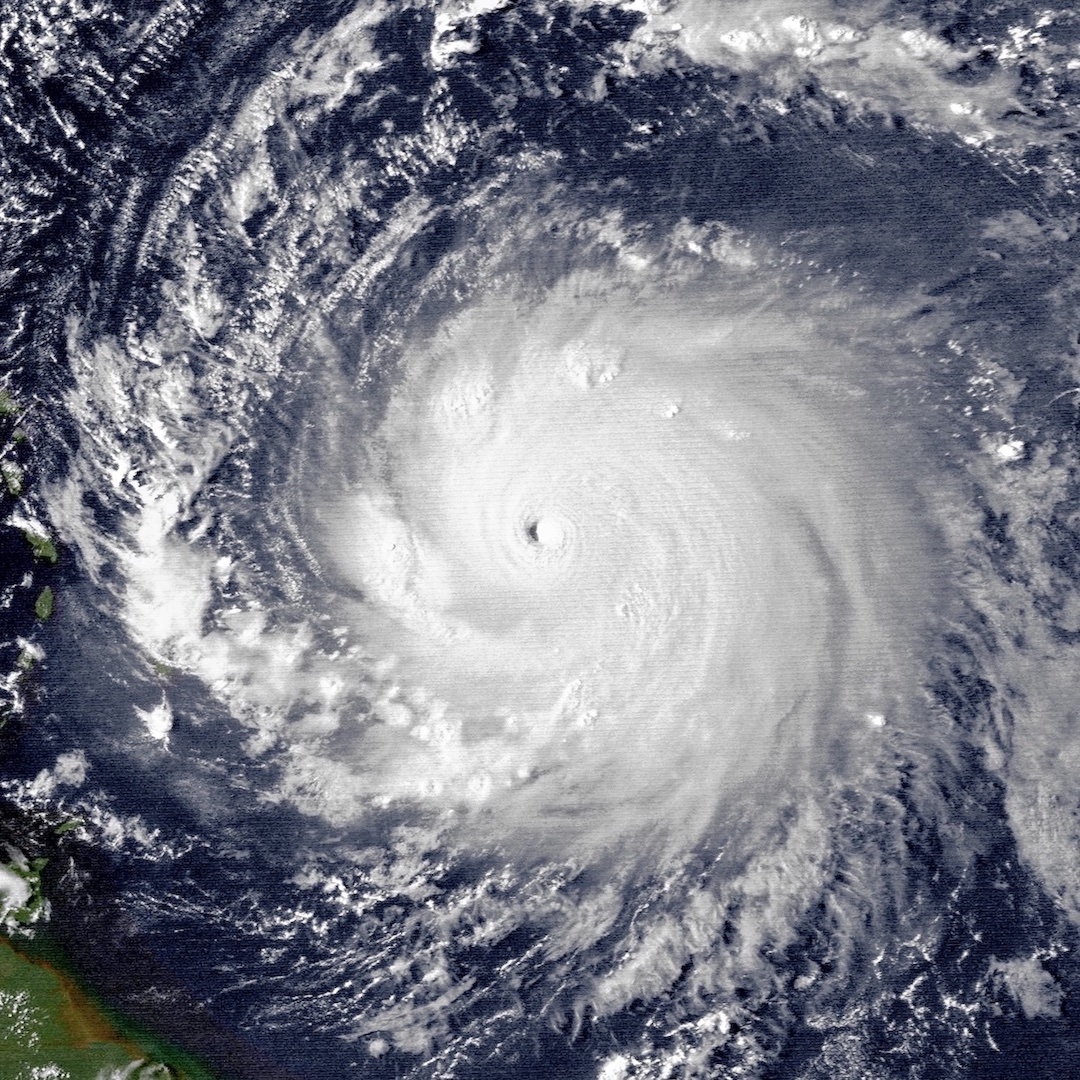

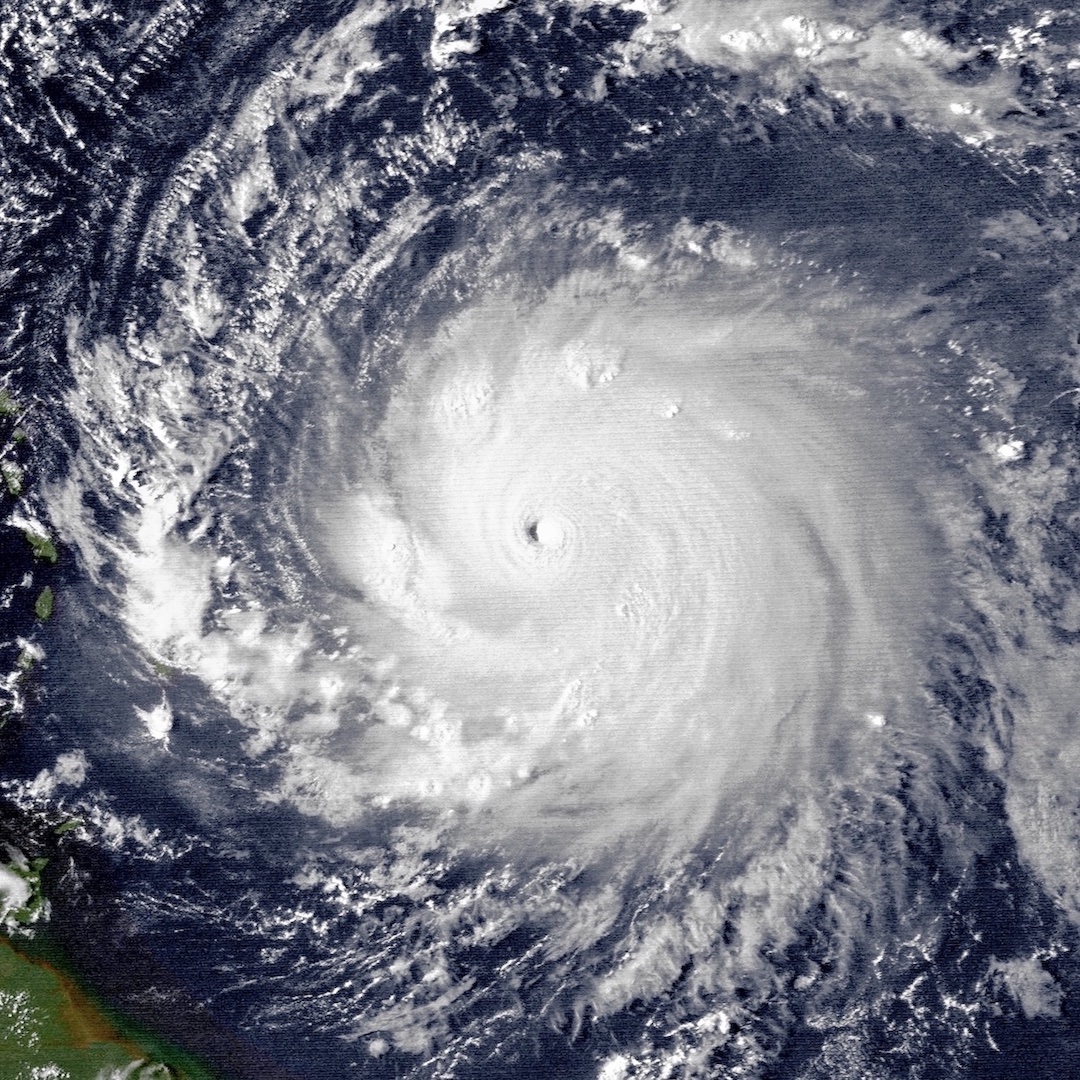

September is peak hurricane season in the Lowcountry of South Carolina, as elsewhere in this part of the Atlantic World. Most of the numerous tropical cyclones that have visited this area over the past three-and-a-half centuries have arrived during the month of September, including the very memorable storm of 1752. Arguably the most destructive storm of eighteenth century South Carolina, the hurricane that passed slightly south and west of Charleston on September 15th, 1752, established a benchmark against which generations of local inhabitants measured all subsequent storms. From a documentary perspective, however, we have just one robust description of the hurricane, published in Charleston four days later in the South Carolina Gazette. Printer Peter Timothy (1724–1782) described it as “the most violent and terrible hurricane that ever was felt in this province.” Since that time, numerous writers have quoted and paraphrased parts of Timothy’s familiar account of the now-famous hurricane.[1]

The South Carolina Gazette of 19 September 1752 reported the loss of nearly every sort of watercraft that happened to be in Charleston Harbor during the storm. While some vessels sank and others were smashed to pieces, some were blown ashore and later recovered. The idea of lifting or towing a large, wooden, three-masted ship from the streets of urban Charleston back to the harbor, or extracting such a vessel from the muddy marshes of Wappoo Creek, sparks my curiosity. Seeking information about the methods used in this work, I noted that Peter Timothy’s published description mentioned the fate of two British warships in Charleston during the hurricane of 1752—the Mermaid and the Hornet. I’ve spent some time delving into the archives of the Royal Navy in London over the past few years, and I wondered if the surviving records of those two warships might shed some new light on this old story. During a recent research trip, I located and examined a number of logbooks and letters written by the officers who survived great Carolina hurricane of 1752, now held at The National Archive, Kew, and at the Caird Library and Archive at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. This program represents my efforts to narrate those records, which definitely augment our understanding of a seminal chapter in Charleston’s natural history. Let’s begin by introducing the characters.

His Majesties Ship Mermaid was a twenty-four-gun, sixth-rate vessel launched in 1749. Its main deck was 115 feet long over a keel length of ninety-six feet, and the hull’s “beam” or widest point measured thirty-two feet (526 tons burthen). The three-masted ship carried a total of 160 men, including a captain, lieutenant, warrant and petty officers, and more than 140 enlisted seamen. The Lords of the Admiralty in London assigned the Mermaid to the Carolina Station in early 1750 and the ship arrived at Charleston in mid-August.[2] The commander, Edward Keller, died one month after his arrival, however, most likely suffering a heat stroke. Captain Elias Bate happened to be in Charleston with HMS Scorpion at that moment, visiting from their assigned post in North Carolina. After a shuffling of naval officers, Captain Bate remained in Charleston with the Mermaid while the Scorpion sailed back to its post.[3]

The slightly smaller Hornet belonged to an unrated class of vessels that the Royal Navy once described as “sloops-of-war.” Launched in 1745, its main deck measured ninety-one feet over a keel length of seventy-four feet, and its beam was twenty-six feet broad (272 tons burthen). The sides were pierced for a total of fourteen carriage guns, and it carried an equal number of swivel guns. Its silhouette resembled that of a two-masted brigantine, but the presence of a small, gaff-rigged mast standing directly behind the main classified it as a snow. The 125 crewmen aboard described the Hornet alternately as a snow or a sloop, but it had little in common with the familiar single-masted sloops of the civilian world.[4] The Hornet came to Charleston by way of Barbados, although the Admiralty had assigned it protect the Bahama Islands. Based in Nassau, the warship was obliged to call at Charleston periodically to careen (a process described in Episode No. 239) and to obtain bulk provisions from naval contractors.

Captain John Hollwall, a career naval officer around thirty years of age, sailed the Hornet to Charleston at the beginning of 1752 to clean and provision the ship as usual. After completing that work, the Hornet departed for the Bahamas, but encountered a severe storm. The rolling seas cracked the vessel’s foremast and rudder, so, after a brief stop at Nassau, the Hornet was obliged returned to South Carolina for repairs.[5] Captain Hollwall steered the snow back into Charleston Harbor in early May and anchored near the town’s busy waterfront, then called “the Bay” but now called East Bay Street.

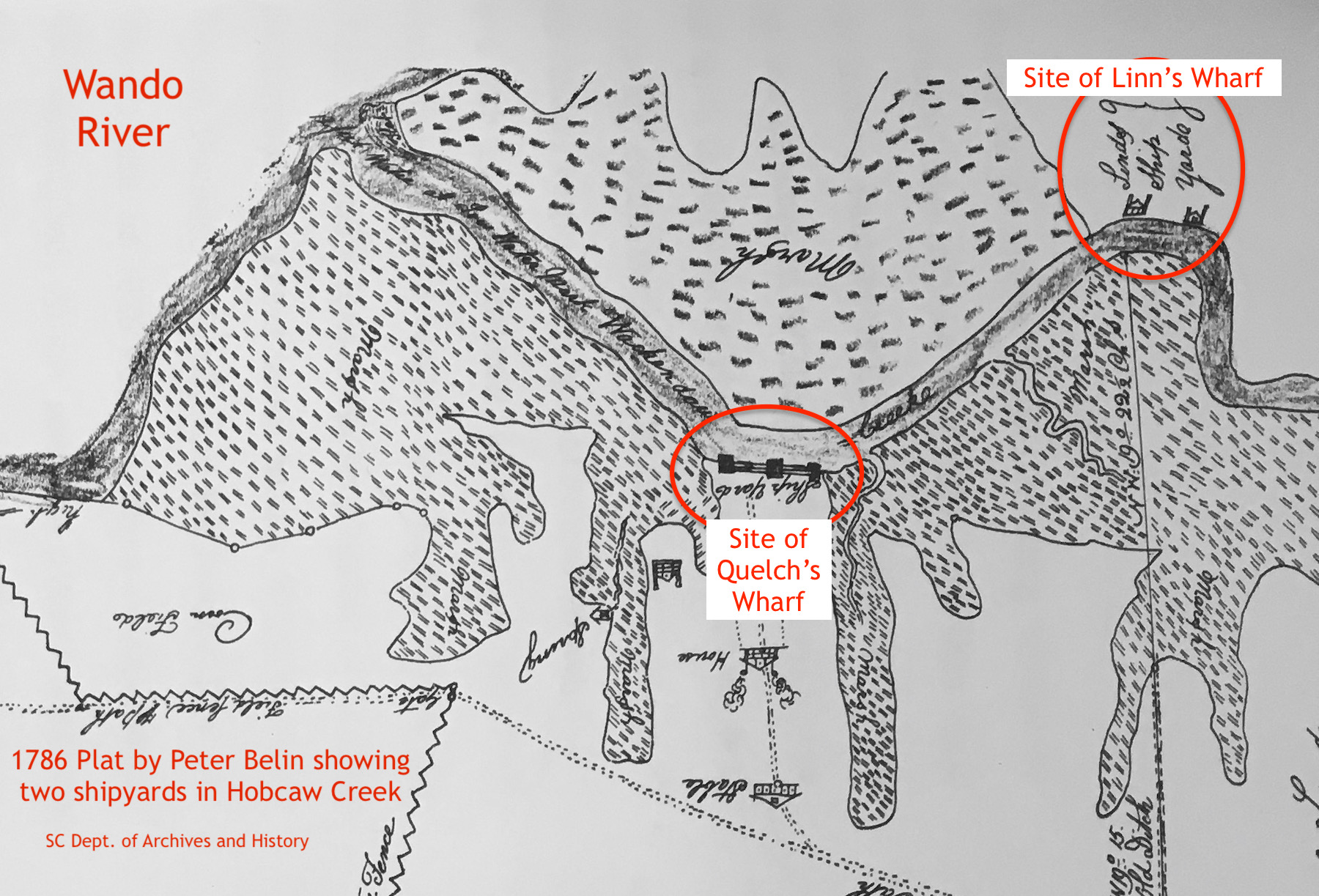

While the crew of the Hornet was fitting a new foremast in the harbor, Captain Bate and the Mermaid were four miles to the north, at David Linn’s careening wharf in Hobcaw Creek. On the morning of May 7th, while the crew was heaving the starboard side of the hull out of the water, several iron bolts and ropes attached to the careening tackle suddenly gave way. The ship’s main mast—measuring two feet in diameter near the base—snapped like a twig just above deck, while the hull splashed down into the water. The falling mast tore away the main shrouds and other standing rigging, destroyed part of the starboard deck, and fractured several deck beams. None of the crewmen were injured at the time, but Captain Bate was probably quite flustered by the ordeal.

Repair work commenced immediately aboard the Mermaid and continued through a stretch of unusually warm spring days. During the third week of May, Lieutenant James John Purcell of the Hornet complained repeatedly in his logbook about the “violent heat,” with temperatures reaching as high as 93 degrees Fahrenheit. On the sultry afternoon of May 25th, Captain Elias Bate suddenly collapsed and, like his predecessor, immediately died, dragging an inky scrawl across the final entry in his logbook. The following day he was buried at St. Philip’s Church, like the many other Royal Navy men who perished in colonial Charleston.[6]

As the highest-ranking naval officer in the area, Captain John Hollwall of the Hornet assumed command of the Mermaid, and ordered Lieutenant James John Purcell to serve as acting captain of the Hornet. Captain Purcell, as he was now styled, was also around thirty years of age, and no doubt embraced the opportunity to advance his rank during the stagnant years of peace between the nations of Europe. While acting-Captain Purcell supervised the completion of repairs to the Hornet in front of Charleston, Captain’s Hollwall’s crew finished repairing the Mermaid in Hobcaw Creek in late June. The larger warship exited the creek and paused briefly in Rebellion Road—the easternmost anchorage in Charleston Harbor—before sailing on a cruise in early July.

Meanwhile, the Hornet sailed northward into Hobcaw Creek on July 5th and commenced the arduous but necessary work of emptying the ship and careening the hull. During the remainder of the summer, Captain Purcell repeatedly complained about what he described as the “great,” “violent,” “extreme,” and “most intense heat.” On the 19th of July, he noted that a Fahrenheit thermometer in the possession of Dr. John Moultrie in Charleston registered 100 degrees in the shade, and 116 degrees in the sun.[7]

The Hornet finished careening in late July, then in early August moored in Charleston Harbor with a pair of anchors stretched fore and aft to brace the snow against the ebb and flow of the daily tides. At fifteen minutes before midnight on the evening of August 14th, a bolt of lightning struck the new foremast and “shivered” the timber to pieces in an instant.[8] A falling mass of debris landed on the forecastle at the bow of the snow and stove the decking into the cook room below. One man was mortally wounded by the explosion, another blinded, and many others bruised by flying debris. Over the next two weeks, the carpenters’ crew aboard the Hornet procured a replacement mast and other timbers from local suppliers and kept busy making repairs.

The Mermaid returned from sea on the morning of August 27th and moored in Charleston Harbor near the Hornet. The next day, Captain Hollwall and his crew watched the men aboard the sloop-of-war raise their new foremast. While the carpenters worked diligently to repair the Hornet during the final days of August, the officers aboard both warships noted the prevalence of breezy, hazy weather with occasional rain. In spite of the inclement weather, the Mermaid unmoored on the morning of September first and sailed into Hobcaw Creek that afternoon. The ship had spent seven weeks sailing through the warm summer waters of the Atlantic Ocean and the crew needed to scrub away the accumulated bio-growth fouling its hull. A more cautious officer might have waited until the end of hurricane season before commencing such work, but Captain Hollwall was trying to be a good steward of the warship under his command.

The Mermaid’s four-mile journey from Charleston Harbor to Quelch’s Shipyard within Hobcaw Creek took place under an increasingly cloudy sky, followed by thunder showers during the early morning of September 2nd. That afternoon, the Mermaid moved northward less than half mile from Quelch’s Wharf to David Linn’s Wharf, located in a broad bend of the serpentine creek. There the crew dropped a single anchor from the bow and “lash’d along side Linns wharf.” The ship’s head was probably pointing to the east, as the crew had done on previous visits, with the larboard (port) side of the hull facing the wharf.

The thunder, lightning, and rain intensified that afternoon, but then dissipated during the evening as the wind increased. At sunrise, the men of His Majesty’s warships and the people of South Carolina witnessed a unique temporal phenomenon in the history of the English-speaking world. As decreed by the British “Calendar Act” of 1751 (see Episode No. 47), the evening of Wednesday, September 2nd, 1752, was immediately followed by the morning of Thursday, September 14th. The British government had planned this global omission of eleven days as a one-time correction to synchronize its calendar (and that of the British colonies) with the calendars used by everyone else in Europe, Africa, and the Near East.

At sunrise on Thursday, September 14th, then, Captain Hollwall in Hobcaw Creek recorded in his logbook the continuation of “hard gales” from the northeast blowing squally, hazy, “uncertain weather” over the Lowcountry of South Carolina. Captain Purcell in Charleston Harbor noted that the tides were “lifting” to an “unusual height,” and that the conditions seemed to be “portending a hurricane.” The ship’s sails had already been stowed below deck during the recent repair work. Now he ordered the crew to bring down the yards, topmasts, and running rigging, all of which they secured on deck to make “all snug in expectation of a hurricane.”

Onshore in Charleston, Peter Timothy reported that the first day of the new calendar was accompanied by “a very hard gale with rain and thick weather.” “The sky looked wild and threatening,” said the printer as the dark clouds continued to stream across the landscape from northeast to southwest. The officers of the Mermaid in Hobcaw Creek noted the continuation of squally weather with thunder, lightning and rain on September 14th, but did not mention any unusual meteorological concerns. The crew spent the day removing the ship’s numerous sails and storing them on shore, and getting their careening gear ready for heaving down at the wharf. They were probably more concerned about avoiding another costly accident than divining the weather approaching from beyond the horizon.

All the sailors in the Lowcountry probably slept fitfully that night as gale-strength winds continued blowing and bands of driving rain drenched the coastal region. All hands aboard His Majesty’s warships rose at four a.m. on Friday, September 15th, as the night watch retired at the end of their customary shift. Conditions on deck were miserable, and, as the officers soon realized, they were growing worse by the minute. In their respective logbooks, Captains Hollwall and Purcell reported that a hurricane “came on with great violence” at six a.m. that morning, just before the onset of the morning flood tide.[9] In urban Charleston, Peter Timothy noted that around nine a.m. “the flood came in like a bore [sic], filling the harbour in a few minutes.”[10]

Within the expanse of Charleston Harbor, the wind from the northeast drove the surging Atlantic tide to the southwest, towards the town’s waterfront and the Ashley River. Numerous small watercraft streamed past the Hornet and smashed against the brick fortification wall protecting East Bay Street. More than two dozen sailing vessels at anchor in the harbor—including ships, snows, brigs, sloops, and schooners—were also blown towards the town, dragging their anchors across the sandy bottom of Charleston Harbor. Most of them tumbled like toys over the brick curtain wall on the east side of East Bay Street, while the wind blew others onto the marshes of James Island, and some into Wappoo Creek, west of the Ashley.

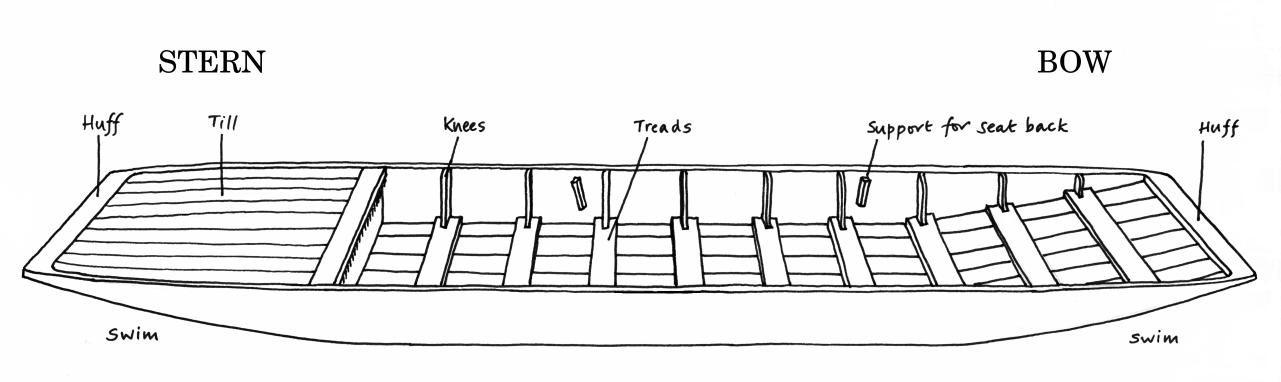

The Hornet was moored with a pair of strong anchors fore and aft, but the surging waves concerned Captain Purcell. Sometime after sunrise, he ordered the crew to drop the auxiliary sheet anchor “under foot” to help steady the ship. “Before 11 o’clock,” recalled Peter Timothy, “all of the vessels in the harbour were onshore, except the Hornet man of war.” The modest warship was not immune to the forces of nature, however. The wind and surging waves were driving the Hornet stern-first toward East Bay Street. Around 11:30 a.m., all three of its anchors were ahead of the bow and the snow was “riding very hard” in the roiling water. The snow’s two boats, which the sailing master described as a “barge” and a “yaul,” both broke loose from the mothership and were “stove to pieces” against the east side of East Bay Street.

The Mermaid also had two boats, one of which had been sent to town earlier for supplies and was never seen again, while the other was washed away from Mr. Linn’s Wharf in Hobcaw Creek. All of the equipment the crew had removed from the ship the previous day and set onshore likewise became airborne and disappeared. Now there was nothing the crew of 160 men could do but hold tight below deck. The upright Mermaid was lashed close to the careening wharf with large hawser cables, but the driving winds from the northeast broke “all the shore fasts” and drove the ship stern-first downstream. Tethered only by a single sheet anchor at the bow, the ship swung to the southeast and southwest like a toy until the anchor began to drag along the muddy bottom. It was shortly before noon when the Mermaid began to plow in reverse across the flooded marsh on the west side of Hobcaw Creek.

The ship’s keel sustained little damage, thanks to the height of the storm surge associated with the hurricane. Both Captains Hollwall and Purcell observed that the tide in the harbor had risen eleven feet higher than the normal spring tides, so the Mermaid’s keel was likely plowing through the blanket of spartina grass that covered the marsh. “About 10 minutes after 11 o’clock,” however, Peter Timothy in Charleston reported that the wind veered from the northeast to east-southeast, south, and then southwest in “very quick” succession. The captain of the Hornet noted the same changes, but placed the dramatic shift at 11:45 a.m. More importantly for the warships, Captain Purcell and his colleagues in the harbor noted that the southerly winds blew with increased violence. Neither of the officers aboard the Mermaid mentioned the wind shift, but they did note its effect: The intense southernly gale blew the ship northward, out of the marsh on the west side of Hobcaw creek. Now driving head-first, the Mermaid dragged its anchor past David Linn’s wharf and onto the highland separating the creek from the marshes adjacent to the Wando River.

Owing to the rather sudden shift of the wind direction, said Peter Timothy, the flood waters in urban Charleston fell more than “five feet in the space of 10 minutes” at some point after 11 a.m. While people in town were drowning in their houses and in the streets, the mariners aboard the Hornet in the harbor were too preoccupied with the savage winds to notice the diminishing waters. Captain Purcell, conferring with his colleagues around the noon hour, noted that the hurricane was “increasing with more violence.” All the other vessels in the harbor had already disappeared, and the officers concluded “that it was impossible for the sloop to ride it out.” Unless they took some immediate action, the vessel was going to capsize and sink or part the anchor cables and smash against the brick fortification wall along East Bay Street. Either of those scenarios would result in the total loss of the Hornet. “The only means to save her,” they concluded, “was to cut away the masts.”

The captain of the two-masted vessel had to decide which to remove first. The crew had just finished replacing the foremast (for the second time in four months), and the greater height and weight of the mainmast rendered it the logical target. Amid the driving rain and howling wind, a pair of crewmen stood on deck swinging axes at the base of the stout timber. Within a few minutes, the intense southerly gale helped snap the mast and propel it over the Hornet’s larboard side. Crewmen immediately gathered the “wreck” of the falling rigging and tackle and hove it overboard. To further lighten the ship, around half-past noon, they jettisoned all the yards, booms, and topmasts that had been secured on deck before the storm. Just as the crewmen were about to raise the axe against the new foremast, however, the wind began to abate. Captain Purcell ordered the men to stay the blade and “let the foremast stand.”

Meanwhile, at Hobcaw Creek, the receding waters and diminishing wind enabled the men aboard the Mermaid to view their surroundings. The ship had driven northward across the flooded terrain and the bow now rested “against a bluff” of high land, approximately three hundred feet north of David Linn’s careening wharf. The stern, on the other hand, was floating above a patch tidal marsh, and officers saw that the Mermaid was beginning to list as the stern slowly descended towards the mud below. Captain Hollwall immediately ordered crewmen overboard into the water, which was still head high, to find materials to brace the hull in an upright position. They gathered a number of spare topmasts—long spars like modern telephone poles—from the ship’s deck and from the damaged shipyard facilities nearby. The receding waters enabled the men to plant a number of the stout timbers in the muddy ground around the ship and brace them against the hull “to shore her up” and “to keep her fast for fear of oversetting.”

The hurricane continued to abate during the afternoon of the 15th. By four p.m., the officers of the Hornet described the weather as “quite moderate” with occasional drizzle. The danger was over, and the crew raised the auxiliary sheet anchor at five p.m. The men aboard the Mermaid also breathed a sigh a relief that evening. None of the king’s mariners died during the ferocious storm, but one man—Duke Sandilands, Master-at-Arms of the Mermaid—died in the early morning hours of September 16th.

After a quiet night of rest in Charleston Harbor, the men aboard the Hornet raised one of the remaining anchors on Saturday morning, September 16th, untangled the twisted pair of fourteen-inch cables, and moored the ship anew with anchors fore and aft. To their west, the waterfront of Charleston was a scene of utter destruction. The town’s wooden wharves, around ten in number, were mangled and almost non-existent. Broken watercraft littered the streets, along with masses of lumber, vegetation, and rubbish. While the king’s mariners attended to their injured ship that afternoon, a messenger from Hobcaw Creek informed Captain Purcell that the Mermaid had been driven ashore during the storm. Captain Hollwall sent orders for the Hornet to sail to Hobcaw and render assistance as soon as possible. Purcell acknowledged his duty, but opined that the snow would require another day or two of work before getting under sail.

On the morning of the 17th, during another thunderstorm, the crew of the Mermaid used the ship’s lower yards to lift the guns (twenty six-pounders and four three-pounders) from the deck and set them ashore. While most of the men continued removing materials to lighten the ship, Captain Hollwall and his subordinates considered the vessel’s awkward situation. The bow, resting on high ground, pointed skyward, but the stern lay several feet lower within an intertidal marsh. The ground surrounding the damaged rudder was mostly dry at low tide, while at high tide the stern was surrounded by water seven feet deep. The most obvious method of freeing the Mermaid, according to the officers, was simply to dig away the mud surrounding the ship and tow it back to Hobcaw Creek. To help expedite the work, Captain Hollwall hired thirteen enslaved men of African descent and two large, flat-bottomed punts from a local contractor.[11] These unfree laborers immediately joined scores of sailors in “digging under the bottom” of the ship and shoveling the spoil into the punts.

Back in Charleston Harbor, the Hornet’s crew was struggling to devise a sailing rig for the battered snow. Only the lower third of its foremast remained standing, having removed the topmast and topgallant mast before the storm and then heaved them overboard with the mainmast and all the yards at the climax of the hurricane. Now the crew bent the fore topsail to a salvaged timber as a makeshift foreyard, and raised a single staysail above the bow. On Monday the 18th, the Hornet unmoored at 2 p.m. in light winds and sailed slowly northward, entering Hobcaw creek two hours later.

While the Mermaid’s crew pitched the ship’s ballast ashore on the 19th, Captain Hollwall and his officers conversed with their colleagues aboard the Hornet about a plan for towing the larger vessel backwards to Hobcaw Creek. On the 20th, they removed the Mermaid’s rudder and tried to determine the most appropriate point on the stern to affix tow ropes. The Hornet’s crew at the same time set out two anchors in the creek and positioned their vessel “to assist in heaving off the Mermaid.”

Confident of the rescue plan underway, Captain Hollwall took time to write to the Admiralty in London to inform the Lords Commissioners of the recent hurricane. In the letter, the captain revised his narrative of the storm’s arrival, but it still contrasts with that published by Peter Timothy. “The wind blew excessively hard here at ENE about 8 o’clock in the morning on the 15th,” wrote the captain. “At 10 o’clock it veer[e]d to the ESE when it was esteem[e]d by every body a most violent hurricane.” Hollwall reported that the Mermaid had been blown from the careening wharf into the marsh, “and when the wind shifted, she drove against a bluff about half a cables length from the wharf, where she was immediately secured as well as possible to prevent her falling over.” The captain’s letter of September 20th contains other nautical details, but I’ll quote one paragraph that contains a more general assessment that might be useful to broader audience (with the original spelling):

“The water upon this occasion rising ten or eleven feet higher then the usual spring tides, yeilded vast destruction, and drowned many people, many houses in Charles Town were washed away, and many of the inhabitants were obliged to swim for their lives: There is not the least appearance of a wharf, bridge or store house [in the area], and such devastation was never before seen in this part of the world. His Majestys sloop Hornet rode it out off the town with only the loss of her main mast and boats. Every other vessel was blown into the town, and now lay high and dry. The Kings Store house [on East Bay Street] is blown down [and] washed away, and the major part of the [ships’] condemned stores intirely lost and destroyed, among the rubbish of the town. Notwithstanding Proclamations were immediately issued by the Governour and Council to prevent pilfering, the Negros plunder’d away, and I am inclined to believe the Kings Store house sufferd as much as any house in town.”

Captain Hollwall informed the Admiralty that he was “endeavouring to gett the Mermaid off the ground by dismasting and digging her out of the mudd, there being but seven feet water at high water where she lays.” He assured officials in London that he would get the Mermaid back to ship shape “with all imaginable dispatch & frugality.”[12] But the task of freeing the ship required more effort than the captain imagined. The mariners’ joint efforts “to heave off the ship” at high tide on September 20th and 21st, using anchor cables affixed to the capstans of both ships, achieved little. Hollwall quickly realized that the Mermaid was too heavy, and its stern too firmly stuck in the mud. The revised solution was to keep digging and devise a method of lifting the ship. To augment their efforts, the captain hired seven more enslaved men and sent mariners abroad to gather empty wooden casks.

The crew’s daily digging was most effective during episodes of low tide, when the men could most easily shovel the mud into the nearby punts. The diggers continued working as the tide rose—standing perhaps waist deep in the water—but were obliged to quit before the normal high tides crested at seven feet. That height rendered digging impossible, of course, but the water was still far too shallow to lift the ship. The draft of a sixth-rate warship in 1752 was approximately twelve feet at the stern; to float the Mermaid, therefore, the water needed to be more than five feet higher. Digging away the mud was not the solution, but simply a necessary prelude the main event.

While the mariners and enslaved men continued digging, other crewmen began to assemble a collection of empty “butts”; that is, wooden casks capable of holding 126 gallons each. The plan was to envelop the ship’s lower hull or bilge with a tight skirt of empty, sealed butts, effectively lowering the ship’s waterline by several feet. Neither of the officers articulated this plan nor their method of attaching the butts to the ship, but the general outline is implied within their nautical lingo. It appears that they encircled the hull with several anchor cables, placed at the height of the normal water line and below, to create a stout girdle around the bilge, and then tied rows of empty butts to the girdling cables. Or to quote the officers, the crewmen were employed in “slinging butts under the bilge” and “lashing them to the ship’s wale.”

The work of slinging butts and digging mud continued through the end of September, while other crewmen worked above deck to lighten the Mermaid. On the afternoon of the 25th, they removed the ship’s bowsprit and mizzen mast and heaved them overboard. On the 26th, they raised a pair of tall timbers amidship and lashed them together to create an A-frame “sheer” crane. On the morning of the 28th, they lifted the foremast out and set it aside. After removing the improvised crane, the crew lashed more empty butts to the hull “to float the ship off with” and continued digging.

All work aboard both warships paused on the afternoon of September 29th as “dark gloomy unsettled weather with thunder lightning & continual rain” evolved into another hurricane the following morning. The storm of September 30th continued with “great violence” during the afternoon, but fortunately its strongest winds were much farther to the south. The storm began to abate by sundown, and the mariners in Hobcaw Creek resumed work the following morning.[13]

Hot, hazy, sultry weather continued throughout the first half of October as seven-score men continued digging around the Mermaid. Captain Purcell detached a crew of carpenters from the Hornet at this time to scour the nearby forest for a tree to serve as the snow’s mainmast. Captain Hollwall discharged the hired caulkers filling the Mermaid’s leaky seams on October 7th, and the crew’s efforts focused exclusively on digging for a further two weeks. Thirty-five days after the catastrophic storm, the crew had created sufficient space around the hull and beneath the stern to deploy their pièce de résistance. On October 20th, the men lashed a final rank of casks to the lowest exposed strakes of the bilge, both fore and aft, and brought the two hired punts astern. They placed one wooden boat on each side of the repaired rudder and lashed a sturdy wooden beam athwart the tops of both punts. The next day at dead low tide, the mariners slid the punts forward and wedged the cross-beam directly below the ship’s sternpost. At seven a.m. on Sunday, October 22nd, the rising spring tide slowly lifted both punts and the mass of wooden butts girdling the Mermaid. By eight a.m., the ship’s keel rose from the mud for the first time in five weeks, followed by great cheers from the waterlogged sailors.

With the help of the nearby Hornet, the king’s mariners towed the Mermaid stern-first back to Hobcaw Creek, removed the girdling butts, and secured the ship alongside Linn’s Wharf. The completion of this long and dirty task merited a celebration, and creative minds saw an opportunity at hand. For those still unaccustomed to the New Style calendar, the afternoon of October 22nd was really the 11th, according to the old calendar, and therefore the anniversary of the coronation of King George II and Queen Caroline. The exhausted crew applied to Captain Hollwall for something extra to drink in order to raise a celebratory toast on the obligatory royal occasion. Faced with a shortage of rations after the recent difficulties, the captain instead gave each enlisted man a Spanish dollar to go to town and buy the drink of his choice. Hollwall was in generous mood that continued into the letter he wrote to the Admiralty on October 24th:

“I have found greater difficulty in getting His Majesty’s Ship Mermaid off the ground than I at first imagin’d, not being so well acquainted with the weight of a twenty gun ship as I could have wish’d some years ago. However the great and good behaviour of my people, convinces me that seamen can do any thing. All hands were obliged to dig five weeks to deepen the water, and by making use of that method we had at spring tides nine feet water all round the ship, which with the assistance of large flatts and a number of butts secur’d to her occasion’d the ship to float on the 22d October, to the great joy of my people, who began to fall down very fast by working so long in the water.”

The captain reported that the ship’s false keel, a sacrificial timber protecting the actual keel, was partially destroyed, “that being the only damage she has receiv’d by laying on the ground.” Hollwall acknowledged the extravagant expense of hiring twenty enslaved men and two punts, but noted that the hired hands “were discharged the moment the ship was off the ground.” He also reported that the Mermaid had lost its boats and oars, most of its powder and related gunners’ stores, and some barrels of provisions that had been condemned anyway. The Hornet likewise lost its boats and oars, the mainmast and its rigging, and a smaller proportion of gunpowder and related stores.[14]

During the final week of October and the first week of November, the crew of the Mermaid re-installed the ship’s bowsprit, foremast, mizzenmast, and the shrouds to support them. The crew of the Hornet likewise installed a new mainmast during the early days of November and raised a new set of yards and shrouds. On November 15th, Captains Hollwall and Purcell agreed that the Mermaid no longer required assistance from the Hornet, and the sloop-of-war was free to withdraw from Hobcaw Creek. The crew raised a few sails and weighed anchor late on the 17th, and anchored before Charleston the following morning.

Then, in mid-November, the crew of the Mermaid picked up where they had left-off two months earlier, before the hurricane. They attached the careening gear to the masts and hove the ship down over the wharf to clean and caulk the hull. The ship was so leaky, or the crew too gun-shy, however, that they could not keep the keel out of the water long enough to address the damage to the false keel. Captain Hollwall, no doubt growing tired of the whole affair, decided to postpone further repairs until the ship returned to England.[15] His inclination for procrastination proved prescient. On November 28th, Captain Purcell received orders from London, dated many months earlier, instructing him to bring the Hornet home by way of Ireland. The snow’s crew finished their repairs, stowed new provisions in the hold, and exited the harbor at sunset on December 18th.

The Mermaid cast off from David Linn’s careening wharf after sunset on the 19th of December and anchored in Hobcaw Creek. The following afternoon the crew weighed anchor and began to move southward towards Quelch’s Shipyard, but the wind blew the ship onto a new sandbar midstream that arrested their progress. On the morning of December 22nd, the warship finally sailed out of Hobcaw Creek into the Wando River, and turned southward for Charleston. There Captain Hollwall received long-delayed orders from England, mistakenly sent to North Carolina, instructing the Mermaid to return home at once.

Owing to a political dilemma beyond the captain’s pay grade, however, the Mermaid did not actually depart from Charleston until June 3rd, 1753. South Carolina’s Royal Governor, James Glen, and his Council were incensed that the Royal Navy would leave such a valuable colony without a guard at a time of weakness. The destructive hurricane of September 1752 had demolished most of the capital’s fortifications, and the Mermaid’s withdrawal before the arrival of another station ship would leave Charleston open to attack from any number of potential enemies.[16]

One might imagine that John Hollwall was ready to bid farewell to the wind-scarred landscape that had brought him so much grief, but he deferred to Governor Glen’s request and cooled his heels in Charleston. In spite of dangerous careening wharves, sultry weather, destructive lightning, and ferocious hurricanes, the palmetto province wasn’t all bad. Perhaps the young captain was simply thankful for the opportunity to rest, some four thousand miles distant from the Lords of the Admiralty in London. It’s worth noting, however, that he departed before the great summer heats spawned another harrowing storm.

And so the annual cycle continues in the twenty-first century: September is not just a dangerous month on the Lowcountry calendar. It’s also a season to reflect on the stories of the past that help us prepare for the future.

Sources Cited In This Essay:

National Archives, Kew:

ADM 51/3908: Captain’s log, Mermaid, 1752–53 (John Hollwall, ca. 1723–1775)

ADM 51/458: Captain’s log, Hornet, 1752–53 (John James Purcell, ca. 1720–1759)

ADM 52/620: Master’s log, Hornet, 1752–53 (John Crews, ca. 1731–1811)

ADM 1/1888: Letters from Captain John Hollwall to the Admiralty, 1752–53

ADM 106/1100: Letters to the Navy Board; from Captains Hollwall and Purcell, 1752 (see items 137, 155, 171, 193a–b; 242, 243, 253, 254, 262).

Caird Library, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich:

ADM/L/M/176: Lieutenant’s log, Mermaid, 1752–53 (Francis Grant, 1730–1803)

ADM/L/H/163: Lieutenant’s log, Hornet, 1752–53 (John Drummond, ca. 1730–1763)

[1] South Carolina Gazette, 19 September 1752, pages 1–2. See, for example, Alexander Hewatt, An Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of the Colonies of South Carolina and Georgia (London: Alexander Donaldson, 1779), volume 2, 180–82; David Ramsay, History of South Carolina (Charleston, David Longworth, 1809), volume 2, 318–20; David M. Ludlam, Early American Hurricanes, 1492–1870 (Boston American Meteorological Society, 1963), 44–47; Jonathan Mercantini, “The Great Carolina Hurricane of 1752,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 103 (October 2002): 351–65; Walter J. Fraser Jr., Lowcountry Hurricanes: Three Centuries of Storms at Sea and Ashore (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009).

[2] For more information about the Mermaid, see Rif Winfield, British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates (Seaforth, 2007), page 400 of e-book edition.

[3] South Carolina Gazette, 6–13 August 1750 (Monday), page 2; South Carolina Gazette, 3–10 September 1750 (Monday), page 2; A. S. Salley Jr., ed., Register of St. Philip’s Parish, Charles Town, South Carolina, 1720–1758 (Charleston, S.C.: Walker, Evans & Cogswell, 1904), 216.

[4] Winfield, British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1714–1792, page 463 of e-book edition.

[5] John Hollwall to the Secretary of the Admiralty, 8 April 1752, ADM 1/1888; John Hollwall to the Navy Board, 15 April 1752, ADM 106/1100/155.

[6] The accident at Linn’s wharf on 7 May 1752 is described in the logbooks of the ship’s officers; Captain Hollwall described the damage and the death of Captain Bate in his letter to the Secretary of the Admiralty, 26 May 1752, ADM 1/1888.

[7] “Calm with most intense heat. At noon Terenheauts [sic; Fahrenheit’s] thermometer in Dr. John Moutreys [sic; Moultrie’s] possession, up at 100 degrees in the shade [and] 116 in the sun.” Captain’s log, Hornet, 19 July 1752, ADM 51/458.

[8] Prior to October 1805, shipboard officers of the Royal Navy recorded the beginning of each calendar day at noon, twelve hours ahead of the civilian day on shore, which commences at midnight. Captain Hollwall, for example, recorded the lightning strike at “1/4 before midnight” under the heading of 15 August, nautical time, which is 11:45 p.m. of 14 August, civil time. Because this concept of nautical time clashes with both the chronology of contemporary terrestrial events and the mindset of modern readers, I have translated into civil time all references to specific dates and hours extracted from the various logbooks in question.

[9] Under the heading of 15 September, Captain Hollwall wrote “at 6 pm the gale increased & blew a hurricane.” This text follows a brief account of earlier “PM” activities (of the afternoon of 15 September, nautical time, or the afternoon of 14 September, civil time) and precedes a description of events that definitely occurred on the morning of the 15th. It is my conclusion, therefore, that Hollwall notation of “6 pm” should read “6 am,” as in the contemporary journal of Captain Purcell.

[10] In contrast to the reports of Captains Hollwall and Purcell and Peter Timothy, Lieutenant Drummond and Master Crews aboard the Hornet both noted that “the hurricane came on” at ten a.m. on the morning of September 15th. Their journals contain much identical language, suggesting they wrote their entries collaboratively at some point after the storm, and probably misremembered the precise time of the events.

[11] In the several pay vouchers he submitted to the Navy Board, Captain Hollwall stated the Charleston-London firm of Messrs. Shubrick & Company had provided the hired slaves and equipment.

[12] John Hollwall to the Secretary of the Admiralty, 20 September 1752 (in duplicate), ADM 1/1888; Hollwall sent a verbatim copy of this letter to the Navy Board, ADM 106/1100, Nos. 242 and 243.

[13] In addition to the descriptions recorded in the naval logbooks, see also Peter Timothy’s description in South Carolina Gazette, 3 October 1752, pages 2–3; Ludlam, Early American Hurricanes, 47–48.

[14] John Hollwall to the Secretary of the Admiralty, 24 October 1752, ADM 1/1888 (in duplicate); Hollwall sent a verbatim copy of this letter to the Navy Board, ADM 106/1100, Nos. 254 and 255.

[15] John Hollwall to the Secretary of the Admiralty, 7 December 1752, ADM 1/1888.

[16] John Hollwall to the Secretary of the Admiralty, 8 January and 29 June 1753, ADM 1/1888.

NEXT: Hispanic Prisoners in Charleston during La Guerra del Asiento

PREVIOUSLY: The Stono Rebellion of 1739: Where Did It Begin?

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments