Juneteenth, Febteenth, and Emancipation Day in Charleston

Processing Request

Processing Request

Commemorating the end of slavery has been an important part of the yearly calendar in numerous communities across the United States since the end of the Civil War, but there is no singular date of observance. Whether one celebrates the demise of human bondage on “Juneteenth,” “Febteenth,” or some other “Emancipation Day,” is largely a matter of geography. Today we’ll delve into the history of general emancipation in this country and then focus on the background of Charleston’s own celebratory traditions. There’s a reason why you’ve never heard of “Febteenth.”

Juneteenth is a holiday celebrated in many parts of the United States every year to commemorate events that took place in Galveston, Texas, on June 19th 1865. On that date, a representative of our Federal Government publicly read aloud orders proclaiming that, “in accordance with a proclamation from the executive of the United States, all slaves are free.” Historians of that region tell us this event communicated the news of emancipation to the last people still held in bondage after the conclusion of the American Civil War. The anniversary of that jubilant scene in southeast Texas has been observed every year since 1866 as “Juneteenth,” and it is indeed a special date in the calendar of many Americans. Not everyone in our vast country understands its meaning, however, and some communities commemorate the end of slavery on a different calendar date. Every year since 1866, for example, the people of Charleston have celebrated “Emancipation Day” on the first day of January. To put the meaning of Juneteenth in a better perspective, therefore, we need to understand the broader context of general emancipation in the 1860s. Race-based slavery, first introduced into North America by Spanish explorers in the early 1500s, did not die with one fatal blow in 1865. Rather, emancipation came to the 3.5 million enslaved people spread across the Southern states at different times over a period of several years.[1]

The Emancipation Proclamation:

The key instrument responsible for the destruction of slavery in the United States was the so-called “Emancipation Proclamation” issued by President Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War in 1863. It may seem strange to think of a brief collection of words toppling a centuries-old practice valued in billions of dollars, but Lincoln’s executive order provided a relatively simple legal and moral framework that streamlined a very lengthy and complicated endeavor that involved the work of numberless individuals. The Proclamation, formally proposed on September 22nd, 1862, and made effective on January 1st, 1863, ordered the immediate emancipation of “all persons held as slaves within any state, or designated part of a state, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States.” It did not apply to enslaved people living within the United States, north and west of the boundaries of the Confederacy, however, or to people in formerly-rebellious areas already under the control of the Union Army, like Tennessee and New Orleans. Those people had to wait until the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in December 1865 to enjoy their legal freedom.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a powerful rhetorical gesture that committed the collective might of the United States to the cause of ending slavery. In practical reality, it had little immediate effect on the lives of enslaved people living in the Confederate States of America. The civil and military authorities controlling those rebellious states ignored Lincoln’s Proclamation as the hollow words of a foreign despot. As the Union Army gained more ground in the rebellious states, however, President Lincoln and his advisors knew that questions would inevitably arise about the civil status of people held in bondage within captured territory. By issuing the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, President Lincoln removed doubt about the status of enslaved people by conferring freedom to them in theory before the Union Army arrived to enforce that freedom in practice.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a powerful rhetorical gesture that committed the collective might of the United States to the cause of ending slavery. In practical reality, it had little immediate effect on the lives of enslaved people living in the Confederate States of America. The civil and military authorities controlling those rebellious states ignored Lincoln’s Proclamation as the hollow words of a foreign despot. As the Union Army gained more ground in the rebellious states, however, President Lincoln and his advisors knew that questions would inevitably arise about the civil status of people held in bondage within captured territory. By issuing the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, President Lincoln removed doubt about the status of enslaved people by conferring freedom to them in theory before the Union Army arrived to enforce that freedom in practice.

The people of Charleston, deep in the heart of the Confederacy, learned about President Lincoln’s initial proclamation of September 1862 and the revised proclamation of January 1863 by way of telegraphic relays from Virginia.[2] In the absence of United States troops to enforce Lincoln’s executive orders, however, there was no change in the status of Charleston’s enslaved population. People living in bondage in this area might have heard about the proclamation in the days and weeks after its debut and privately expressed their elation, but they were not yet in any position to assert or enjoy their freedom. In contrast, the recently-freed people around Beaufort, South Carolina, were already enjoying their new status.

Following their victory at the Battle of Port Royal in November 1861, Union forces took command of a number of the sea Islands in that vicinity as white property owners fled the advancing army. Many thousands of enslaved people living on scores of plantations were suddenly without masters, but their civil status was not immediately clear. Federal authorities initially referred to them as “contraband” because every individual represented human property that had been separated from his or her legal owner (as in “contraband property”). They were considered “freedmen” and “freedwomen” in 1862, at which time the Federal government commenced a social “experiment” to help them transition into full citizenship. That important work helped to pave the way for the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which sought to clarify the status of future freedmen and women.[3]

“Febteenth”: The Emancipation of Charleston:

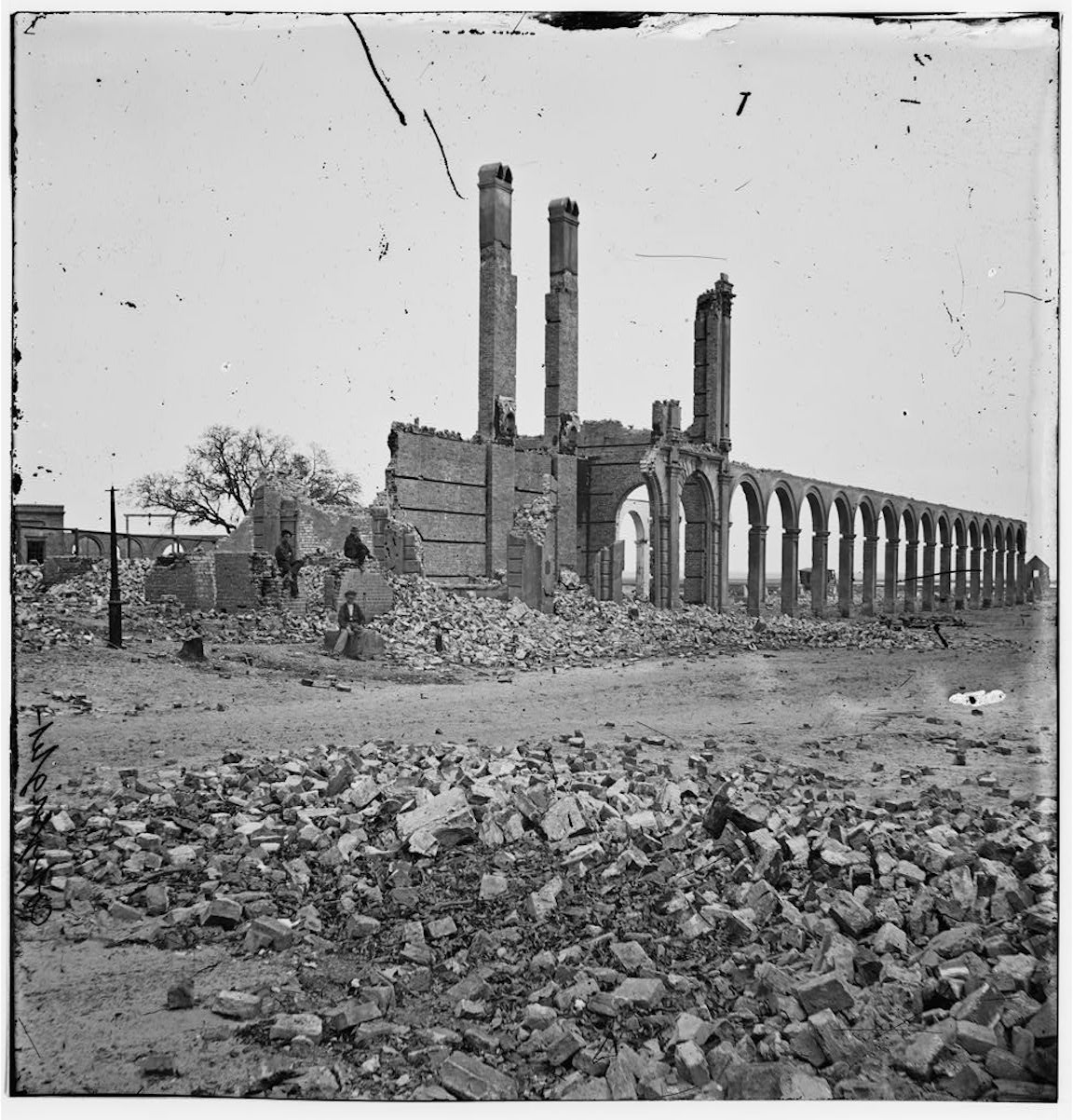

As the city that had sparked the war of secession in 1861, Charleston was the special object of attention from the United States military. The U.S. Navy began blockading the harbor in late 1861, but could not capture the city by sea alone. After inching slowly northward from Beaufort to Morris Island in 1863, the U.S. Army began shelling the city on near-daily basis in late August. Most of Charleston’s civilian population had evacuated by 1864, leaving the city in the hands of a reduced number of enslaved servants, laborers, shopkeepers, civil servants, and military personnel. Confederate forces began to evacuate Charleston on February 15th, 1865, and completed most of that work on the evening of the 17th. In the early morning hours of Saturday, February 18th, the last of the Confederate guards in the city set alight a number of warehouses containing thousands of cotton bales, set fuses to destroy three Confederate warships in dock, and then retreated northward. As the sun rose over Charleston that morning, a number of fires belched smoke and embers into the sky, igniting other fires throughout the city, while a series of explosions killed scores of ragged civilians searching for food.[4]

As the city that had sparked the war of secession in 1861, Charleston was the special object of attention from the United States military. The U.S. Navy began blockading the harbor in late 1861, but could not capture the city by sea alone. After inching slowly northward from Beaufort to Morris Island in 1863, the U.S. Army began shelling the city on near-daily basis in late August. Most of Charleston’s civilian population had evacuated by 1864, leaving the city in the hands of a reduced number of enslaved servants, laborers, shopkeepers, civil servants, and military personnel. Confederate forces began to evacuate Charleston on February 15th, 1865, and completed most of that work on the evening of the 17th. In the early morning hours of Saturday, February 18th, the last of the Confederate guards in the city set alight a number of warehouses containing thousands of cotton bales, set fuses to destroy three Confederate warships in dock, and then retreated northward. As the sun rose over Charleston that morning, a number of fires belched smoke and embers into the sky, igniting other fires throughout the city, while a series of explosions killed scores of ragged civilians searching for food.[4]

The first U.S. troops to enter Charleston steamed across the harbor from Morris Island and landed at South Atlantic Wharf, at the east end of Gillon Street, between nine and ten on the morning of February 18th. The first boots on the ground were few in number, and their movements tentative. Reinforcements soon arrived, and soldiers in blue began to move cautiously through the smoke-filled streets. Their primary objective was to confirm the evacuation of Confederate forces and to secure outposts throughout the city. In coordination with Charleston’s mayor and the city’s municipal fire department, Union soldiers then helped battle the fires raging throughout the city and attended to the hundreds of civilians killed and wounded by the explosion of the Northeastern Railroad depot at the east end of Chapel Street.[5]

Most of the remaining Charlestonians stayed indoors during the anxious transition of power on February 18th, but some hungry souls ventured out to greet the Union soldiers. At the end of the day, Federal officials reported back to Washington D.C. that “nearly all the inhabitants remaining in the city belong to the poorer classes.”[6] That is to say, the vast majority of Charleston’s reduced local population in February 1865 were people of African descent. With the exception of a small number of free persons of color, they had been slaves on Friday the 17th, but became free on Saturday the 18th. Surviving reports from military eye-witnesses on the ground that day tell us little about the initial reaction of the black community to this change of status. There are no reports of celebrations, cheers, or any sort of public demonstrations to mark the long-awaited arrival of general emancipation. In accordance with President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, the enslaved people of occupied Charleston were now considered free. Union soldiers moving through the streets to secure the city might have conveyed this information to individuals they encountered, but we have no written record of how quickly or widely that information spread throughout the community.

Through interaction with Union soldiers and through the grapevine of personal communication, news of the peaceful transition of power in urban Charleston spread throughout the local community over the weekend of Saturday and Sunday, the 18th and 19th of February, 1865. Formerly enslaved people might have been elated by this news, but it’s possible that some also harbored a bit of reluctance to believe that emancipation had indeed finally arrived. They had long anticipated such a day, and perhaps hesitated to embrace the prize out of fear of being disappointed and perhaps even chastised. In the succeeding days, however, the arrival of more Union troops fostered an increasing confidence that a new day had truly dawned on the peninsula. Our first confirmation of this budding process comes from several brief interviews conducted by Northern journalists just forty-eight hours after the fall of Charleston.

Major-General Quincy Gillmore, stationed at Hilton Head Island, was the commanding officer of the Union soldiers that first occupied Charleston in mid-February, 1865. After the initial troops had entered the city on the morning of February 18th, General Gillmore paid a brief personal visit to Charleston that evening before steaming back to his headquarters. His return to the Palmetto City on the morning of Monday, February 20th, was a much grander affair. His flag steamer, W. W. Coit, carried the post band, a large retinue of Union officers, and a number of civilian ladies curious to see the fallen city.[7] Among the general’s entourage were also two newspaper reporters—James Redpath of the New York Tribune and Charles Carleton Coffin of the Boston Daily Journal. In the days and weeks after the fall of Charleston, both men published valuable first-hand accounts of conversations with freedmen and freedwomen that capture the spirit of the hour. In the interest of brevity, I’ll mention just one story, from Mr. Coffin’s report to the Boston Journal, as an example of their encounters.

It is impossible for me to give a complete representation of the joy of the freedmen of this city over the arrival of the Yankees. On Monday morning last [February 20th], when the steamer W. W. Coit, with Gen. Gillmore’s flag at the fore and the Stars and Stripes at the stern, steamed up the harbor, with the band playing ‘Hail Columbia,’ there was a sudden gathering of colored people upon the wharves. They were full of ecstasy. Springing upon the pier before the lines were thrown out, I met a gray-bearded old man, who touched his hat, bowed himself to the ground and said, “Good morning, massa.”

“We are Yankees, Uncle. Are you not afraid of us?” I said.

“God bless you, no, Massa. I've prayed for you to come, and God has heard me,’ he said, grasping my hand. He threw his old battered hat upon the ground, looked upward and poured out his gratitude from an overflowing heart.

“Are you a slave?"

“Yes, Massa.”

“Well, you are a slave no longer. You are as free as I am.”

“Is it so, Massa?" he asked with indescribable earnestness, and again raising his eyes toward Heaven, he gave thanks to God, with an emotion such as I never before witnessed.[8]

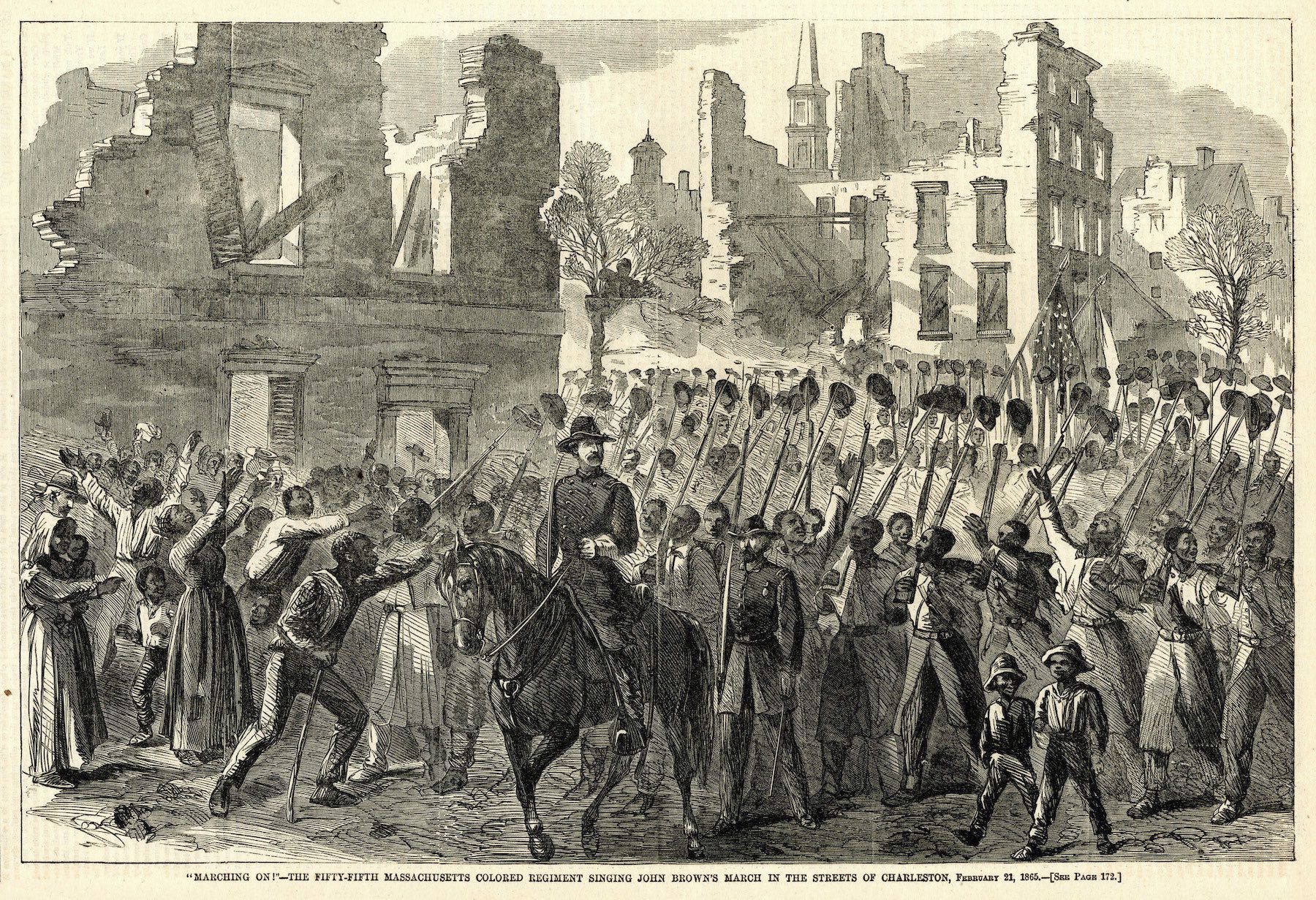

Reporters Coffin and Redpath were soon followed by others from Northern papers who described the transformation of war-torn Charleston to eager readers beyond the South. We learn that on Tuesday, February 21st, for example, the 55th Massachusetts Regiment of black soldiers arrived and paraded up Meeting Street. Along the way, the soldiers sang “John Brown’s Body” and were accompanied by throngs of formerly-enslaved men and women who joined in the chorus. The more-famous Massachusetts 54th Regiment arrived soon afterwards, and also received an emotionally enthusiastic reception from the freed community.

Reporters Coffin and Redpath were soon followed by others from Northern papers who described the transformation of war-torn Charleston to eager readers beyond the South. We learn that on Tuesday, February 21st, for example, the 55th Massachusetts Regiment of black soldiers arrived and paraded up Meeting Street. Along the way, the soldiers sang “John Brown’s Body” and were accompanied by throngs of formerly-enslaved men and women who joined in the chorus. The more-famous Massachusetts 54th Regiment arrived soon afterwards, and also received an emotionally enthusiastic reception from the freed community.

The first blush of emancipation celebration in Charleston in the spring of 1865 culminated with an elaborate spectacle and parade on March 21st. The “Freedmen’s Jubilee,” as the press called it, was organized by the black elders of both Zion and Bethel Methodist churches, and included more than four thousand participants. Assembling between noon and 2 p.m. on Citadel Green (now Marion Square), the revelers marched behind a pair of mounted black marshals, fifty butchers with a bright banner, and the 21st Regiment of United States Colored Troops with their band (which included many South Carolina natives). The procession followed King Street south to White Point Garden, up East Bay to Broad Street, and from Meeting Street back to the public green. The parade included other bands, clergymen, firemen, tradesmen, clubs, and more than eighteen hundred children dressed in their finest threads. One especially creative cart carried women and children whose hands were bound with rope, while a mock auctioneer harangued the crowd with the now-banished words of the now-illegal slave sale. They were followed by a hearse carrying an elaborately decorated coffin bearing the inscription “Slavery is Dead,” and followed by a train of mourners dressed in black.[9]

In the months that followed the ecstatic Freedmen’s Jubilee, the formerly-enslaved people of Charleston continued to forge new lives of personal liberty, while civil and military officials wrestled with the difficult task of beginning to reconstruct the city and state governments. The initial joy of achieving freedom gradually gave way to new routines of mundane survival in a new society, but local freedmen and women did not take their liberty for granted. In social circles and within the revitalized African Methodist Episcopal Church, they planned and organized annual events to commemorate the arrival of freedom and the death of slavery. Beginning in 1866 and continuing to the present, the anniversary of emancipation has been celebrated every year in Charleston with a parade, church services, and general thanksgiving.

Unlike the people of Galveston, Texas, who choose to commemorate the date on which they first heard the news of emancipation, June 19th, the newly-freed people of Charleston did not mark the anniversary of their freedom on February 18th—the day Union soldiers entered the city and told them they were free. Nor did they establish a tradition of repeating the Freedmen’s Jubilee of March 21st. They chose instead the first day of January, the date of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, and in 1866 inaugurated an unbroken tradition of celebrating that date each year as Emancipation Day (see Episode No 46).

For reasons known only to those freedmen and freedwomen living in Charleston in the 1860s, the memory of the events of February 18th did not seem to hold any special significance within the local community. We have no tradition of celebrating “Febteenth,” as we might call it, within the Palmetto City, at least in any public manifestation. Back in 2015, I hosted a program at the Charleston County Public Library on February 18th to mark the 150th anniversary of the end of slavery here. The response was small, and I don’t recall hearing about any other similar commemorations. Nevertheless, I’m not suggesting we need to create a new “Febteenth” holiday. The traditions created by our forebearers in the 1860s carry sufficient weight to keep their spirit alive.

By collectively choosing to celebrate the anniversary of emancipation on January 1st, 1866, the recently-freed people of Charleston were likely memorializing an important but otherwise unrecorded fact. Public readings of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation have been a conspicuous part of local commemorations since 1866, and that document clearly held some special significance to the formerly-enslaved people who inaugurated these traditions. Based on all of the aforementioned facts, it appears that the enslaved people living in Charleston had heard the news of Lincoln’s executive orders emancipating people held in bondage in the Confederate States long before the arrival of Union soldiers. The Proclamations of 1862 and 1863 were widely reported and discussed in newspapers on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. By word-of-mouth, knowledge of these important documents was easily disseminated to illiterate people far and wide. We can imagine, therefore, that the enslaved people of Charleston celebrated privately in 1863 when they heard of Lincoln’s Proclamation, and held their collective breath with fierce anticipation. As the president had anticipated, the act of Union soldiers entering Charleston on February 18th, 1865, did not bestow freedom, but rather confirmed and finally enforced the emancipation guaranteed by proclamation two years earlier.

Conclusion:

General emancipation came to the enslaved people of Charleston on February 18th, 1865, and the community paraded in celebration of that fact four weeks later, on March 21st. In every subsequent year, from 1866 to the present, the people of Charleston have commemorated the anniversary of emancipation with a parade and other events held on January 1st. They chose to mark this date as “Emancipation Day,” rather than February 18th or March 21st, to acknowledge the gravity of the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1st, 1863. That executive order focused the nation’s energies and resources on defeating the institution of slavery, and laid the groundwork for their general emancipation in Charleston in the late winter of 1865.

General emancipation came to the enslaved people of Charleston on February 18th, 1865, and the community paraded in celebration of that fact four weeks later, on March 21st. In every subsequent year, from 1866 to the present, the people of Charleston have commemorated the anniversary of emancipation with a parade and other events held on January 1st. They chose to mark this date as “Emancipation Day,” rather than February 18th or March 21st, to acknowledge the gravity of the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1st, 1863. That executive order focused the nation’s energies and resources on defeating the institution of slavery, and laid the groundwork for their general emancipation in Charleston in the late winter of 1865.

The annual celebration of Juneteenth on June 19th represents a parallel holiday to Charleston’s own Emancipation Day observed on January 1st. Both events commemorate the death of slavery, but each is rooted in its own particular local history. Whether one chooses to celebrate emancipation on June 19th, February 18th, January 1st, or some other date on the calendar is a matter of personal choice, but the sentiment is worthy of general attention. The eradication of race-based slavery was a major milestone in the history of this community and this nation. It was the culmination of many generations of struggle against injustice, and it set the United States on a path towards the noble goal of civil equality. More than one hundred and fifty-five years later, however, that mission is not yet complete, and the conversation about civil rights continues. By pausing at least once each year to acknowledge the meaning and value of Juneteenth and Emancipation Day, we gain the strength to focus on the prize of true liberty and justice for all.

[1] The enslaved people of Galveston, Texas, were not the last to be held in bondage in the United States, and the endeavor to identify the “last” enslaved people in this country is fraught with complexities. For more information about this topic, see Ira Berlin, The Long Emancipation: The Demise of Slavery in the United States (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992).

[2] See the front page of Charleston Mercury, issues of 29 September 1862 and 6 January 1863.

[3] For more information about this topic, see Willie Lee Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999).

[4] For a description of the bombardment of Charleston, see E. Milby Burton, The Siege of Charleston, 1861–1865 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1970); for the occupation of the city, see Charleston Courier, 20 February 1865, page 1.

[5] For a first-hand descriptions of the initial movements of the Union forces, see the report of Lieutenant Colonel Augustus G. Bennett in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, series 1, volume 47, part 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1895), 1018–20.

[6] Report of General Quincy A. Gillmore to General H. W. Halleck, Chief of Staff, Washington, D.C., in The War of the Rebellion, series 1, volume 47, part 1, 1007–8. Other useful descriptions appear in Wilbert L. Jenkins, Seizing the New Day: African Americans in Post-Civil War Charleston (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 30–45; and Charles Carleton Coffin, The Boys of ’61, or Four Years of Fighting (Boston: Estes and Lauriat, 1881), 462–84.

[7] Charleston Courier, 20 February 1865 (Monday), reported that General Gillmore “was in the city a few hours Saturday, but left the same evening for Hilton Head.” His return on February 20th was described in Charleston Courier, 21 February 1865 page 1.

[8] The text of Coffin’s report to the Boston Daily Journal was reproduced in New York Times, 6 March, 1865, page 8, “The Slave Mart.” You can read more compelling quotes in chapter 29 of Coffin’s 1881 publication, The Boys of ’61, or Four Years of Fighting.

[9] Charleston Courier, issues of 22 March 1865 and 23 March 1865. See also Ethan J. Kytle and Blain Roberts, Denmark Vesey’s Garden: Slavery and Memory in the Cradle of the Confederacy (New York: The New Press, 2018), 42–45.

PREVIOUS: The Rise of Charleston’s Horn Work, Part 2

NEXT: Remembering Charleston’s Liberty Tree, Part 1

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments