John Champneys and His Controversial Row, Part 2

Processing Request

Processing Request

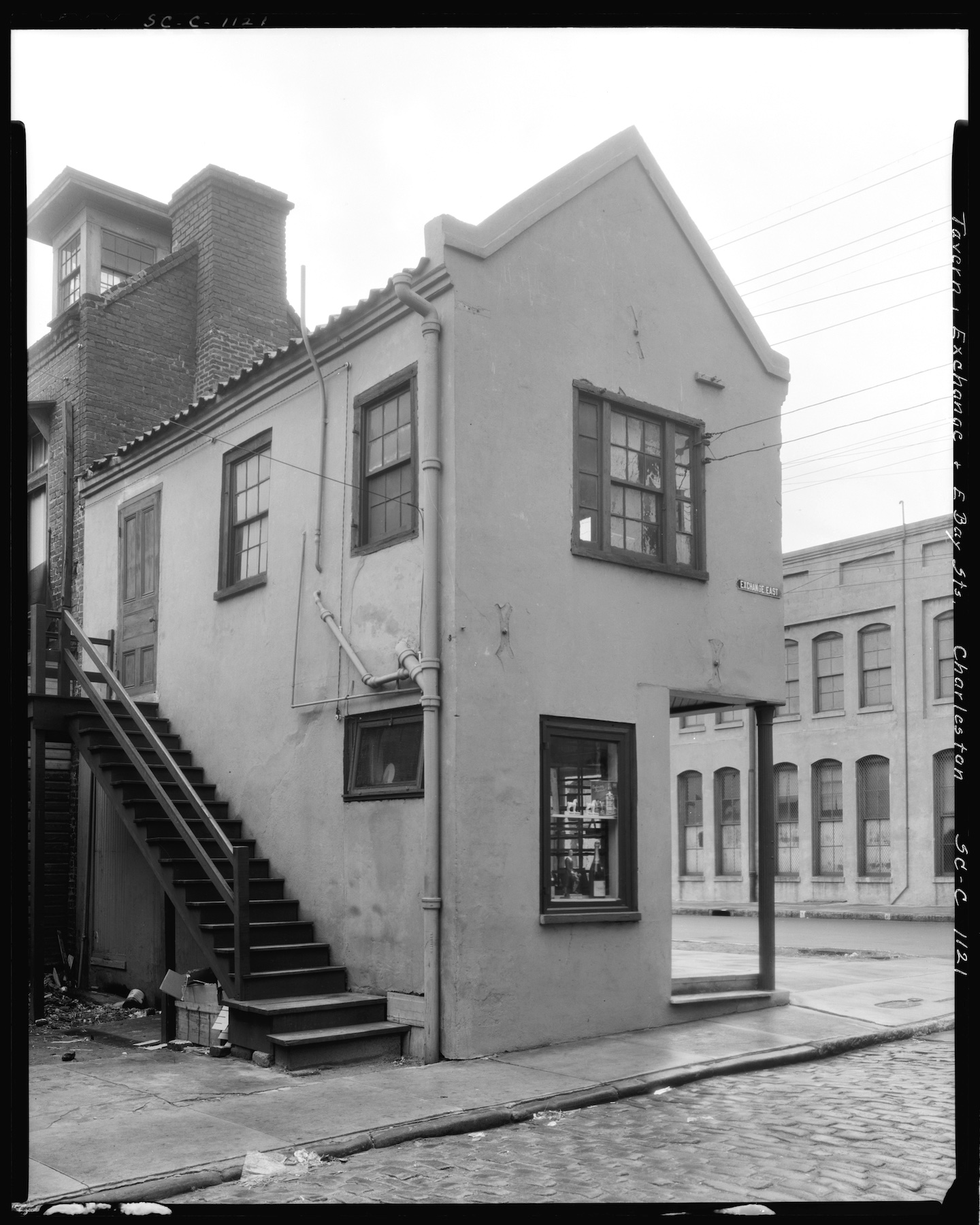

Champneys’ Row was a conspicuous anomaly in urban Charleston in 1781. Besides the prominent and ornamental Exchange next door, the slender range of four brick stores was then the only civilian edifice adjacent to the brick curtain wall defining the eastern edge of East Bay Street. The building’s novel placement and two-story height violated provincial laws of 1736 and 1738 governing structures erected to the east of the curtain line, and the community sought to punish its owner, John Champneys, by erasing his footprint from the city in 1783.

As I mentioned in the first part of this story, South Carolina’s Commissioners of Fortifications published a notice in early June 1783 directing the owner of Champneys’ Row to dismantle the offending building by July 4th or suffer its demolition. Mr. Champneys had already fled the state, however, as a notorious loyalist to the British Crown who was unwelcome in the newly-independent United States. Several weeks after the publication of the notice, members of the South Carolina General Assembly read a petition from several merchants renting “one of those tenements within the range of buildings erected by John Champneys, near the Exchange on land reserved to the publick.” Trading under the name Smiths, DeSaussure, and Darrell, the merchants paid rent to the Commissioners of Forfeited Estates and were “apprehensive that the said Commissioners may soon dispose of the said building, with orders for removal thereof, to the great distress of your petitioners for want of a store to remove into.” They asked the legislature for “permission to retain the tenement they now possess, or the whole range of [the] building,” and to continue paying rent for the same, “whereby your petitioners will have time, either to build or purchase some other store proper for their trade and commerce.”[1]

Although the legislature did not formally respond to the merchants’ petition, the state was not deaf to their plea. Champneys’ Row stood unmolested for the remainder of 1783, while its owner was in exile in Florida and the Commissioners of Forfeited Estates continued to collect rent from the merchants occupying what they described as the “New Buildings, on the Bay.”[2] The property was still subject to John Champneys’ 1771 mortgage to the estate of Benjamin Smith, however, and the Smith family sought the money long overdue to them. To satisfy the outstanding mortgage and accomplish the goals of the Confiscation Act of 1782, the state agreed for the Sheriff of Charleston District to sell all of Champneys’ Wharf at public auction in early 1784.

Advertisements for the sheriffs’ sale, published in February, noted that the premises included “the range of brick stores thereon fronting the Bay, which now let for a considerable rent, but are subject to the incumbrance of being pulled down by order the Commissioners of Fortifications, agreeable to an Act of the General Assembly.”[3] Champneys was still in St. Augustine at that moment, but the definitive treaty of peace between Britain and the United States, ratified in January 1784, permitted displaced loyalists to return to their former homes for twelve months in order to settle their affairs.[4] John sailed from St. Augustine to Charleston with his small family in March, just in time to coordinate with a family member to attend the auction on his behalf.

On 25 March 1784, Sheriff Daniel Stevens (formerly clerk and business partner of John Champneys) stood on the north side of the Exchange to auction the wharf property located to the east and south of that landmark building. The highest bidder was Roger Parker Saunders of St. Paul’s Parish, Colleton County, a patriotic veteran of the American Revolution, member of the South Carolina House of Representatives, and first cousin to John Champneys. The sale price was £7617.18.9, of which Sheriff Stevens delivered £2000 to the Smith family to satisfy John’s outstanding mortgage, and the remainder to the state Commissioners of Forfeited Estates.[5] Saunders, an affluent planter with limited experience in wharf management, was only the nominal purchaser, however. Later documents demonstrate that he merely held the premises in trust for the use of Mary Champneys and her loyalist husband, but the political circumstances of the day required them to screen this family arrangement from official public notice.[6]

One day after the sale of Champneys’ Wharf and its four brick stores, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified a statute with direct implications for the future of that property. To enlarge the powers of the recently-incorporated City Council of Charleston, the state invested the municipal government with the authority formerly exercised by the Commissioners of Fortifications, relating specifically to “the pulling down or removing [of] any building or other erection on any of the wharves, or within fifty feet of the curtain line on the Bay of Charleston.” The new law also empowered City Council to permit the erection of wharf buildings anywhere to the east of the curtain wall, as long as such structures were “not more than six feet in height, or thirty feet wide, and that the whole be of one uniform construction.”[7] While these legislative changes did not specifically repeal the colonial-era laws governing the buildings standing to the east of East Bay Street, they effectively refocused public debate of the topic. The new law empowered the city government to condone the geographic placement of Champneys’ Row, previously deemed illegally proximate to the old curtain wall, but made such acceptance contingent on the reduction of the two-story building to a height of no more than six feet.

Details of City Council’s enforcement of such powers after March 1784 are critically important to the narrative of Champneys’ Row and subsequent structures of a similar character. As I described in Episode No. 79, however, the looting and destruction of city property during the spring of 1865 resulted in the loss of Charleston’s earliest municipal records, including documents relating to negotiations with either John Champneys or his cousin, Roger Parker Saunders. Contemporary newspapers, property conveyances, and state records provide some valuable clues, but this archival patchwork requires careful interpretation to reconstruct the most significant chapter in the story of Champneys’ Row. In short, the building was physically reduced in height sometime after the spring of 1784 in compliance with the law, but details of the chronology and the physical extent of such alterations are now lost.

We know, for example, that the mercantile firm of Smiths, DeSaussure, and Darrell removed from Champneys’ Row to a store in Tradd Street immediately after the auction in late March 1784.[8] Days later, in mid-April, John Champneys was threatened by a group of anonymous citizens, no doubt veterans of the recent war, who sought to force him to flee the state. Reports of this and similar episodes of intimidation in Charleston prompted the governor to issue a proclamation on April 28th emphasizing the legal protection afforded to loyalist visitors by the terms of the Anglo-American peace treaty.[9]

In May 1784, Champneys published an anonymous advertisement offering to sell “the four new stores near the Exchange,” which he acknowledged were “liable to be brought to the height allowed by the legislature.” Potential buyers could purchase the units “either as they now stand, or they will as soon as possible be put into the form allowed by the corporation.”[10] In other words, the building and its roof were intact in early May 1784, but Champneys or a new owner would soon be obliged to reduce its height in accordance with the directions of Charleston’s City Council (i.e., no taller than six feet high). The sale attracted no buyers, and the lack of subsequent newspaper data suggests that the building was unoccupied and perhaps not in a habitable state for the remainder of the year. The work of dismantling the roof and removing the upper courses of brickwork must have required the owners to expend money for labor, but the extent of such work is unknown. For reasons now unclear but perhaps related to demolition, Roger Parker Saunders mortgaged all of Champneys’ Wharf in August 1784, including the brick stores, to the familiar executors of the estate of Benjamin Smith as collateral for a loan.[11]

In February 1785, near the expiration of his one-year sojourn in Charleston, John Champneys was apparently reluctant to bid farewell to his family and homeland. A petition he submitted to the state legislature at that time hints at his frame of mind. He first asked to receive “the balance arising from the sale of his wharf” in March 1784, which he claimed would enable him “to satisfy his other creditors and save somewhat for the support of his family.” Secondly, he asked to become a citizen of South Carolina. He had returned from exile merely to settle his affairs in the state, but now Champneys confessed that he was “desirous of passing the remainder of his days amongst family and friends, in a country to which he wishes to be bound in future by the strictest ties of allegiance.”[12] Although a committee of the state House of Representatives recommended granting both of Champneys’ requests that March, the majority of the House rejected his petition.[13]

Also in March 1785, a local commission merchant named John Hatter began advertising that he conducted business from an office at “No. 1, the south-east corner of the Exchange,” and later in the year described this address as part of Champneys’ Row.[14] Hatter, a friend of the Champneys family and a member of the state legislature, had apparently rehabilitated the northernmost of the four brick stores. Champneys himself was soon obliged to leave Charleston, and might have asked Hatter to oversee similar alterations to the remaining three stores. Following a three-month extension granted by the Governor of South Carolina, John Champneys left his wife and daughter in Charleston and sailed for England in the summer of 1785.[15]

In August of that same year, Champneys’ cousin, Roger Parker Saunders, briefly advertised to sell “the four valuable stores on the curtain line,” forming part of Champneys’ Wharf. His description of the property seems to confirm the that the building had been altered to some unknown degree. While boasting that “the situation of these stores cannot be equaled in this city, either for the ship-chandlery, liquor, factorage, or vendue business,” Saunders acknowledged that some portion of the building—perhaps three-fourths of it—lacked a roof. He advised prospective purchasers that the row of brick stores “may be covered at a little expence, with a durable terrace.”[16] This use of the term “terrace” likely refers to a compound popular in the Charleston area during the American Revolution, when imported slate and roofing tiles were in short supply. A local recipe for “terrace” published in 1778 describes a mixture of equal parts lime, tar, and train oil (i.e., rendered whale blubber), whipped into a paste that dried into a semi-flexible coating resistant to both water and fire. By adding an inexpensive roof and a durable coat of terrace, implied Mr. Saunders, the stores at Champneys’ Row would make a fine investment.[17]

John Hatter, who had occupied the northernmost unit of Champneys’ Row since early 1785, advertised that November to lease “three very commodious brick stores on Champneys’s Wharf, with paved cellars,” which “may be enter’d on immediately.” Hatter’s choice of words, employing a common phrase from his day, implies that the stores in question were both unoccupied and fit for immediate use. It appears, therefore, that Hatter might have extended an inexpensive roof over the three empty stores to help generate rental income for his friends Champneys and Saunders. Despite months of constant advertising, which continued into February 1786, the property remained vacant, and Hatter soon withdrew from business in Charleston.[18]

John Champneys, meanwhile, was in London requesting aid from the British government. Loyalty to the Crown during the War of Independence had caused thousands of Americans like Champneys to lose their property and income. To reward their fidelity, the British government established a board of commissioners to review numerous claims for war-time losses and to determine appropriate compensation. Champneys submitted a written memorial, schedule of losses, and affidavits from witnesses to his suffering in South Carolina. These materials provide valuable details of his efforts to expand his Charleston wharf, including the construction of the four controversial brick stores in 1781. John admitted that he had recently petitioned the state legislature for permission to regain his property and become a citizen of the state, but he had been rejected and sailed to England for help. Although he claimed losses totaling more than £20,000 sterling, the British commissioners eventually awarded Champneys the handsome sum of £5204.[19]

Back in Charleston during the spring of 1786, a community debate about the future of the waterfront inspired hope for the prosperity of the Champneys family. The conversation arose from general disappointment with the state law of March 1784 that had empowered Charleston’s City Council to condemn the height of Champneys’ Row. That same law had authorized the municipal government to permit the erection of one-story buildings abutting the east side of the curtain line, and, two years later, citizens complained that the proliferation of small wooden tippling houses in that formerly-vacant area had created a serious nuisance. The Intendant and Wardens of the city government were similarly disappointed by the 1784 law, but offered a constructive solution. If the state was willing to repeal the existing building restrictions pertaining to property on the east side of East Bay Street, and if every owner of wharf property was willing to cede a few feet of land to widen and straighten that busy street, then the parties might jointly obliterate the physical and legal vestiges of the colonial-era curtain wall and resolve their respective grievances in a manner beneficial to the community in general.[20]

A legislative committee appointed to consider these issues spent several days in early March 1786 researching the legal history of the old curtain wall and interviewing current owners of wharf property. Their subsequent report embraced the plan proposed by City Council and recommended the creation of a bill to accomplish such goals.[21] During the third week of March, both the Senate and House of Representatives read and considered “a bill for repealing such Acts of Assembly as regulate and restrict the erection of houses below the curtain line of Charleston, to widen the Bay Street, and to permit houses of any size to be erected to the eastward of the same.” Owing to a profusion of business, and perhaps some local resistance, however, the House of Representatives chose to postpone further consideration of the matter to the next annual session of the state legislature.[22]

The legislative gestures of March 1786 towards repealing the old building restrictions relative to the east side of East Bay Street apparently inspired optimism within the Champneys family circle. Although the state had postponed ratification of the proposed bill, the exercise demonstrated a strong will in the community to abolish the outdated regulations that had stifled the economic potential of Champneys’ Row over the past several years. Within two months of these legislative developments, some sort of construction was taking place at the southeast corner of East Bay and Exchange Streets (then known as Champneys’ Street). Documentary sources offer few clues to the extent of this work, but physical evidence within the bricks and mortar might suggest that workers restored the walls to their original height and raised a proper roof.

On the first of June 1786, an unknown agent (perhaps Roger Parker Saunders) advertised to sell “those four valuable brick stores, lately built upon the Curtain Line, Champney’s [sic] Wharf, south of the Exchange.” The sparse text of the newspaper notice offered no details of the building’s dimensions or the nature of the ongoing work, but it did note that “the inside work will soon be completed.”[23] Four weeks later, a local vendue master advertised a public auction in early July for “the four brick stores lately finished on the curtain line, near to and south of the Exchange.”[24] Although the stores did not attract a purchaser during the summer of 1786, they were soon ready for rental tenants. At some point in September 1786, for example, the commission mercantile firm of Huxham, Courtney, & Eales moved their office from Church Street to one of the middle stores in Champneys’ Row, which they described as being “two doors [from the] south side of the Exchange.”[25]

The South Carolina General Assembly convened in Charleston in early 1787 to conclude old business and consider new matters. Besides entertaining debates of the deferred bill relating to the old curtain line, the legislature read a petition from Mary Champneys of Charleston, who sought permission for her husband’s return to South Carolina. Because the House of Representatives had rejected his request to become a citizen in 1785, John now wished to settle his debts, liquidate the family’s remaining property, and “remove his family to Europe.” To support her request, Mary attached a petition signed by a number of citizens recommending John’s return, and opined that his presence would be “agreeable to nine tenths of the good citizens of the state who know him.”[26] The legislature soon consented to the brief return of John Champneys, and, in late March 1787, ratified the deferred bill to repeal all laws restricting the buildings on the east side of East Bay Street in order to widen and straighten the busy thoroughfare.[27]

John Champneys was back in Charleston by November 1787, when he and Mary joined their neighbors in conveying to City Council a few feet of land along the western edge of their four brick stores to widen East Bay Street to its present width.[28] The present sidewalk along the west side of Champneys’ Row represents their gift to the City of Charleston. A few months later, the state legislature considered a bill to remove Champneys from the Confiscation List of 1782, but the profusion of business at the end of the session deferred its ratification. John petitioned the state legislature again in January 1789, asking once more to be removed from the confiscation list and to become a citizen of South Carolina.[29] The intervening years had softened local resentment, and in early March the General Assembly ratified a law “to exempt John Champneys from the pains and penalties of the Act of Confiscation.”[30]

Having been banished from his native land in 1777, John Champneys officially became a citizen of South Carolina on 25 March 1789. Three days later, Roger Parker Saunders formally conveyed ownership of Champneys’ Wharf and Champneys’ Row to his cousin John for a nominal consideration.[31] A few days after that transaction, John and Mary Champneys sold the row’s southernmost store to a widow named Mary Meyers.[32] Newspaper advertisements published during the next several years demonstrate that the shops at the southeast corner of East Bay and Champneys’ Street hosted a series of tenants engaged in a variety of commercial trades. Their rental payments helped the Champneys family rebuild their lives in the Lowcountry of South Carolina and to pay off debts dating back to early days of the American Revolution.

John and Mary Champneys sold their three remaining brick stores at the corner of East Bay Street in December 1794 to James George and Daniel O’Hara, trustees for Catherine Coates.[33] Catherine was the wife of ship captain Thomas Coates and, as a legally-independent “feme sole” or “sole trader,” she was the proprietress of the Globe Tavern on the west side of East Bay Street, opposite Champneys’ Row.[34] The trustees, relatives of Catherine, purchased the three stores as investment property to generate a stream of rental income to support Catherine while her husband was at sea.[35] Champneys’ Row became known as Coates’s Row during the early months of 1795.[36] In November of the same year, Catherine Coates announced that she was moving her Globe Tavern enterprise to “the tavern on the Bay, lately occupied by Mr. Harris.” She remained in business at that location, now 153 East Bay Street, until the spring of 1799.[37]

In the meantime, Roger Parker Saunders died in December 1795.[38] Mary Champneys, John’s second wife, died in April 1800. Eight months later, he married Amarinthia Lowndes Saunders, the widow of his cousin Roger. The third Mrs. Champneys and her husband spent much of their senior years at a family plantation on Wallace Creek in St. Paul’s Parish, where they cultivated world-famous roses in a formal English garden. They both died in Charleston, however—Amarinthia in 1817 and John in 1820.[39]

The heirs of Catherine Coates, who died in 1824, conveyed her property in Coates’s Row to different parties, but the full list of individual owners and tenants associated with these historic stores over the past two-and-a-half centuries is far too long to recite. Among them were insurance agents, commission merchants, freight facilitators, printers, paint dealers, and similar mercantile concerns. The ever-changing roster of tenants also included several merchants licensed to sell wine and spirituous liquors for consumption off premises. That tradition changed in April 1880 with the debut of a saloon called “The Cabinet” at what is now 118 East Bay Street, second door south of the Exchange. South Carolina’s tea-totaling dispensary law forced the closure of “The Cabinet” and other saloons in July 1893, however, and Champneys’ Row has been dry ever since.[40]

Anyone strolling by 118 East Bay Street today will notice that its projecting wooden façade differs from the other three stores in the row, and its taller roofline bears a surmounting cupola. These architectural modifications were made sometime after auctioneer Abraham Ottolengui purchased the store in November 1842 and before October 1861, when it became the principal office of Alonzo J. White, the last of Charleston’s prosperous slave brokers formerly doing business on Broad Street.[41] The firm of A. J. White & Son used the premises for office work rather than for human sales, and their post-war business continued at 118 East Bay through the end of 1879.[42]

The powerful Charleston earthquake of 31 August 1886 caused significant damage to Champneys’ Row. The gable or upper part of the south wall collapsed, and the buckling north wall had to be supported with props until it was rebuilt. The east-facing wall suffered minimal damage, but the western wall, facing East Bay Street, was badly cracked at the north and south ends.[43] Repairs were made soon afterwards, almost exactly one century after the Champneys family completed their own modifications to the building. The present corner entrance at 120 East Bay, supported by a single cast-iron pillar, was almost certainly part of the post-earthquake repairs.

By the turn of the twentieth century, few in Charleston remembered John Champneys or the controversy surrounding the construction of his slender brick row. Some of the stores remained vacant for stretches of years, and a real estate broker suggested in 1920 that a bit of effort might transform vacant numbers 114, 116, and 118 into excellent offices.[44] Eola Willis’s 1928 article about the building, which I mentioned at the beginning of this story, focused attention on the northernmost store, No. 120, which she mistakenly believed had been a rowdy tavern in the late eighteenth century. That romanticized tale was inaccurate, but it renewed attention in the old building during the first flowering of Charleston’s tourist trade. Besides providing tour guides with colorful material, Willis’s article also inspired the opening of the liquor store at the corner of East Bay and Exchange Streets, known as “The Tavern” since July 1935.[45]

My goal in this two-part program was not simply to upstage Eola Willis, but to reconstruct an intriguing and important story in the history of our community. By following the tribulations of John Champneys and his kin before, during, and after the America Revolution, we gain a better understanding of life in the Lowcountry during that tumultuous era. By following the trail of clues relating to his brick building, we also gain insight into a critical transition in the history of Charleston’s built environment. Champneys’ Row brazenly violated the city’s zoning traditions in 1781, for which Champneys and his building suffered consequences. As public opinion matured, however, both the owner and his row were soon restored to their former vitality. Charlestonians of the 1780s gradually warmed to the sight of substantial buildings standing on the east side of East Bay Street, and many fine buildings now boast such an address. For this important pivot in public policy and all of its consequences for the present streetscape, we can thank John Champneys and his controversial row.

[1] Petition of George Smith and Daniel DeSaussure, 2 August 1783, SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, 1783, No. 403. The reverse side of this one-page document contains an inscription written by a legislative clerk, nothing that the petition was “ordd. to lie on the table.”

[2] See the advertisement of Smiths, DeSaussure, & Darrell in SCGGA, 2–6 December 1783, page 1; for rent collected by the Commissioners of Forfeited Estates, see SCDAH, Account of the Cash collected by the Commissioners of Forfeited Estates for rent of houses, stores, wharves, etc. (series S390008), 1784, item 2.

[3] SCGGA, 31 January–3 February 1784, page 1. The sale, originally planned for 26 February, was postponed to 25 March 1784; see the sheriff’s notice in South Carolina Weekly Gazette, 27 February 1784, page 3.

[4] See Article 5 of the Treaty of Paris, signed 3 September 1783 and ratified by the U.S. Congress on 14 January 1784.

[5] Daniel Stevens, Sheriff of Charleston District, release to Roger Parker Saunders, 25 March 1784, CCRD P5: 305–10. A surveyor’s plat of the property, made just a few weeks before the sale and annexed to the deed of release, depicts the outline of Champneys’ Wharf but does not illustrate the four brick stores or any other features. Champneys complained about the state of South Carolina taking the bulk of the 1784 sale proceeds in NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 375, 384. For a brief biography of Saunders, see Walter B. Edgar and N. Louise Bailey, eds., Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives, volume 3 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1981), 634.

[6] Champneys described Saunders as “only the nominal purchaser” at the 1784 sheriff’s sale, “being a trustee for Mrs. Champneys . . . who was a native of Chs. Town”; see NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 384–85. In his 1789 deed of conveyance to John Champneys, Saunders stated that he “did not purchase the same entirely to his own use and behoof but IN TRUST . . . for the sole and absolute use and behoof of Mary Champneys (wife of the said John Champneys)”; see Roger Parker Saunders and Amarinthia, his wife, to John Champneys, lease and release, 27–28 March 1789, CCRD F6: 39–43.

[7] See sections IV and V of Act No. 1228, “An Act to explain and amend an Act entitled ‘An Act to incorporate Charleston;’ and to enlarge the powers of the City Council,” ratified on 26 March 1784, in David J. McCord, The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, A. S. Johnston, 1840), 101–2.

[8] The firm announced its removal to Tradd Street in SCGGA, 15–17 April 1784, page 1.

[9] NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 374; the text of the Governor Guerard’s proclamation appears in South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, 27–29 April 1784, page 1.

[10] South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, 4–6 May 1784, page 4.” Champneys’ name does not appear on this advertisement, which directed interested parties to call at No. 12 Tradd Street. An advertisement for a sheriff’s sale in South Carolina Weekly Gazette, 29 June 1785, page 3, offered “that very valuable lot and tenement in Tradd-street, No. 12, now occupied by Mr. Champneys . . . late the property of Alexander Harvey,” the brother-in-law of John Champneys.

[11] Roger Parker Saunders to Thomas Smith and Isaac Motte, executors of the estate of Benjamin Smith, mortgage by lease and release, 17–18 August 1784, CCRD M5: 260–62. Saunders mortgaged Champneys’ Wharf as collateral for the repayment of £1,813.15.1 sterling due 1 January 1785, with interest of seven percent per annum.

[12] Petition of John Champneys, 11 February 1785, SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, 1785, No. 38. For an overview of context of Champneys’ activity during and after the Revolution, see Rebecca Brannon, From Revolution to Reunion: The Reintegration of the South Carolina Loyalists (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2016), 53–54, 79–80, 82–90, 97, 116–17, 120, 185 note 38.

[13] Adams and Lumpkin, Journals of the House of Representatives, 1785–1786, 235–36 (15 March 1785).

[14] Columbian Herald, 7 March 1785, page 3; South Carolina Weekly Gazette, 17 November 1785, page 3.

[15] See the governor’s notification of a three-month extension in SCGGA, 19 March 1785, page 2; in his memorial to the British commissioners, NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 376, Champneys stated that he was obliged to leave sometime after the publication of the governor’s extension on 17 March 1785, while the affidavit of James Carsan, page 387, states that Champneys departed in October 1785. A brief summary of Champneys’ case in Gregory Palmer, Biographical Sketches of Loyalists in the American Revolution (Westport, CT: Meckler Publishing, 1984), 147, confirms that he departed Charleston in 1785 after a stay of fifteen months.

[16] Columbian Herald, 1 August 1785, page 3.

[17] SCAGG, 31 December 1778, page 1. For another reference to the use of the term “terrace” to mean a type of roofing material, see the text of “An Act for repealing such Acts of Assembly as regulate and restrict the erection of houses below the Curtain Line on the Bay of Charleston; to widen Bay-street, and to permit houses of any size to be erected to the eastward of the same,” ratified on 27 March 1787, which appears in Charleston Morning Post, 28 April 1787, page 2, and is found among the engrossed Acts of the Assembly at SCDAH.

[18] SCWG, 17 November 1785, page 3; Hatter announced the expiration of his co-partnership with George Fardo in Charleston Evening Gazette, 24 December 1785, page 3.

[19] Palmer, Biographical Sketches of Loyalists in the American Revolution, 147.

[20] Published Journals of the House of Representatives, 1785–1786, 412–13 (16 February 1786).

[21] Published Journals of the House of Representatives, 1785–1786, p. 501–2 (8 March 1786). The text of this report does not appear in the original manuscript journal of the House of Representatives; the editor of the published version of that journal inserted the text from an extant, loose manuscript, now catalogued at SCDAH as Records of the General Assembly, Committee Reports, 1786, No. 127, which includes a notation, dated 14 March 1786, that the report was “agreed to & a bill ordered to be brot. in agreeable to the report of the committee.” The text of this committee report also appears in the Charleston Year Book for 1896, 414–16: The text begins with a letter dated 4 April 1896 from Thomas E. Richardson, who says he found the following report among the papers of his ancestor, Thomas Eveleigh.

[22] Published Journals of the House of Representatives, 1785–1786, pp. 539, 571 (15 and 18 March 1786).

[23] State Gazette of South Carolina, 1 June 1786, page 3.

[24] Charleston Morning Post, 28 June 1786, page 3.

[25] See their advertisements in Charleston Evening Gazette, 18 August 1786, page 1; Charleston Morning Post, 6 October 1786, page 4; Charleston Morning Post, 7 June 1787, page 3.

[26] Petition of Marcy Champneys, 28 February 1787, SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, 1787, No. 39.

[27] A citation for the 1787 act in question appears in note 17 above.

[28] Wharf Owners to the City of Charleston, lease and release and plat, 19–20 November 1787, CCRD A8: 1–4.

[29] Petition of John Champneys, 16 January 1789, SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, 1789, No. 31.

[30] Act No. 1435, “An Act to exempt John Champneys from the pains and penalties of the Act of Confiscation,” ratified on 7 March 1789, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 5 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1839), 94.

[31] Roger Parker Saunders and Amarinthia, his wife, to John Champneys, lease and release for five and ten shillings (nominal money), respectively, 27–28 March 1789, CCRD F6: 39–43. Note that this conveyance did not include a square parcel of land located immediately to the east of Champneys’ Row, which Saunders sold to William Smith by indentures of lease and release dated 1–2 August 1785, CCRD P5: 475–83.

[32] John Champneys to Mary Meyers, widow, lease and release, 1–2 April 1789, CCRD T6: 39–41.

[33] John Champneys and Mary, his wife, to James George and Daniel O’Hara, lease and release, 28–29 December 1794, CCRD M6: 163–67. Mrs. Coates and her trustees then mortgaged the property to John Champneys by indentures of lease and release dated 30 December 1794 and 1 January 1795, in CCRD M6: 167–72. A note included in that document contains Champneys’ acknowledgment that the mortgage was satisfied on 15 August 1798. Mary Champneys renounced her dower rights in the property on an unspecified date in 1795; see Mary Champneys, wife of John Champneys, renunciation to James George and Daniel O’Hara, trustees for Catherine Coats [sic], wife of Thomas Coates, in SCDAH, Charleston County Court of Commons Pleas, Renunciation of Dower Books, Book 1792 (part 2), pages 263–64.

[34] Catherine Coates announced the opening of the Globe Tavern in [Charleston, S.C.] City Gazette, 23 August 1793, page 3; One “Magann,” a watchmaker at No. 3 Champneys’ Row, described his location as “south of the Exchange, opposite the Globe tavern” in City Gazette, 15 November 1794, page 3.

[35] Catherine George and Thomas Coats [sic] were married on 7 March 1782, during the British occupation of Charleston; see D. E. Huger Smith and A. S. Salley, Jr., eds., Register of St. Philip’s Parish, Charles Town, or Charleston, S.C., 1754–1810 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1971), 215.

[36] An advertisement for the sloop Romeo in City Gazette, 26 November 1795, page 2, described the office of Henry Ellison as “No. 1, Coates’s Row, late Champney’s [sic] Row.”

[37] City Gazette, 19 November 1795, page 2. Several subsequent notices confirm that the building known as the new Globe Tavern, formerly Harris’s Tavern, belonged to the estate of barber and vintner Edward McCrady; see the estate auction notice in City Gazette, 12 December 1795, page 3; the local news in Columbian Herald, 14 June 1796, page 3; Mrs. Coates’s long room advertisement in City Gazette, 28 December 1796, page 3; and the advertisement of John McCrady in City Gazette, 28 March 1799, page 3.

[38] See the local news in City Gazette, 5 January 1796, page 2.

[39] Smith and Salley, Register of St. Philip’s Parish, 1754–1810, 364; City Gazette, 19 December 1800, page 3; Charleston Post and Courier, “Jilted by history, gardener of a famous Charleston rose finds modern defenders,” by Paul Bowers, 14 April 2019.

[40] Charleston News and Courier, 3 April 1880, page 4, “Too Late for Classification. ¶ The Cabinet”; at that time, the business address was No. 58 East Bay Street; News and Courier, 1 July 1893, page 8, “Birth of the Blind Tiger”; the furnishings of “The Cabinet” were advertised in News and Courier, 14 September 1893, page 5, “C. C. Tighe, Auctioneer.”

[41] White purchased the property from the estate of Ottolengui at auction; see Alonzo J. White to James Tupper, Master in Equity, mortgage, 10 November 1859, CCRD K14: 66.

[42] White & Son conducted their slave sales at Ryan’s Mart in Chalmers Street and elsewhere; see, for example, Courier, 17 October 1861, page 2; Courier, 20 September 1865, page 3. White’s executors sold the property in 1896; see Blake L. White, George L. Buist, and A. R. Buffington to Thomas P. Costello, conveyance of title, 7 January 1896, CCRD W22: 71.

[43] Materials on the Charleston Earthquake of 1886 (microfilm), South Carolina History Room, Charleston County Public Library: “Report of Committee on Condition of Buildings after the Earthquake, with a List of Buildings that Should Come Down,” 3.

[44] News and Courier, 29 February 1920, page 6, “Why Rent An Office?” For vacancy at 114 and 116 East Bay Street, see the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of 1884 (page 15), 1886 (page 15), and 1902 (page 78).

[45] News and Courier, 3 July 1935, page 14, “Announcing the Opening of The Tavern, Inc. Retail Liquors.”

NEXT: Hog Island to Patriots Point: A Brief History

PREVIOUSLY: John Champneys and His Controversial Row, Part 1

See more from Charleston Time Machine