John Champneys and His Controversial Row, Part 1

Processing Request

Processing Request

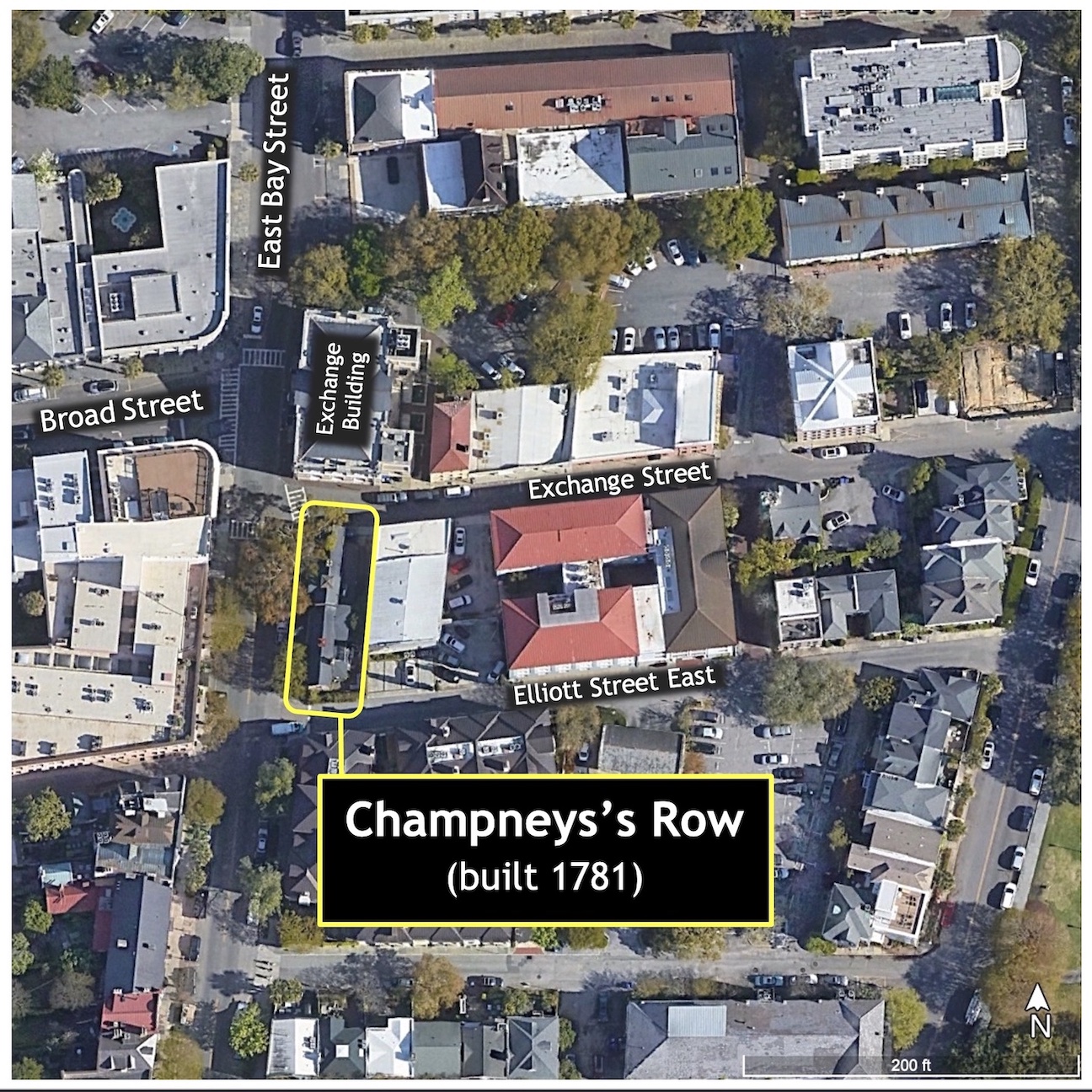

John Champneys was a Charleston factor and wharf owner whose loyalty to the British Crown deranged his life during the American Revolution. While surviving documents provide details of his imprisonment, exile, and return, the slender row of brick stores Champneys built during the war at the southeast corner of East Bay and Exchange Streets bears silent witness to his tumultuous experience. To illuminate their dramatic yet forgotten story, we’ll trace the rise and fall and rehabilitation of both John Champneys and his controversial, confiscated, and truncated row.

The brick building in question, divided into four units, has been identified as Nos. 114–120 East Bay Street since the last major renumbering of Charleston’s street addresses in 1886. Locals and visitors who pass this site, just south of the famous Old Exchange Building, encounter a range of colorful but speculative assertions regarding its history. Such stories share a common root—a newspaper article published in 1928 by a well-meaning but unskilled amateur historian named Eola Willis. As part of a series of essays about early taverns in Charleston, Willis misidentified the northernmost unit of this brick row, No. 120 East Bay Street, as the site of “Harris’s Tavern” in the late eighteenth century.[1] Harris’s Tavern, in fact, occupied the spacious building formerly known as McCrady’s Tavern, now No. 153 East Bay Street, and the rest of the Willis’s narrative about No. 120 is similarly inaccurate.[2] An equally-fanciful newspaper article published in 1942 identified the same property as “Coates’s Row,” belonging to Captain Thomas Coates, a mariner who hosted sailors at a rowdy tavern on the premises.[3] Thomas was never associated with the building, however, which a set of businessmen held in trust for his wife, Catherine Coates, as investment property. An even more romanticized article published in 1969 embellished the mythology of Harris and Coates without mentioning a shred of documentary or physical evidence.[4] In 1997, the popular book The Buildings of Charleston included a good synopsis of the published pseudo-history of Coates’s Row, but did not offer any factual insight.[5]

Despite these literary shortcomings, a very robust paper trail survives for the history of the brick building at 114–120 East Bay Street. The preamble of the site’s real story begins with an undeniable premise: No buildings of any kind occupied the site prior to the construction of the present structure in 1781. This location on the east side of East Bay Street was adjacent to the brick “wharf wall” or “curtain line” that defined the boundary between wharf and street in colonial-era Charleston. In a series of laws ratified between 1694 and 1738, South Carolina’s provincial legislature established zoning regulations about what could and could not be built in proximity to the half-mile long brick wall that was designed to prevent the street from eroding into the Cooper River and to help defend Charleston in case of invasion (see Episode No. 249).

A statute adopted in May 1736, for example, prohibited the erection of any structure on the wharves to the east of the curtain line more than sixteen feet tall. A law ratified in March 1738 and enforced through 1785 prohibited the erection of any structure of any kind within fifty feet of the east side of the curtain wall. All of these colonial-era laws reserved to the government the right to demolish any or all of the buildings to the east of the curtain wall in case of invasion or military emergency. In 1743, for example, during a war with Spain, South Carolina’s provincial government measured and condemned a number of wharf buildings, and then in 1745 carved a moat, twelve feet wide, through a half-mile stretch of land immediately east of the curtain wall.[6] Enemy forces did not attack the town, however, and the moat was filled in 1764—right at the beginning of the commercial career of one John Champneys.

John Champneys was born in Charleston in January 1744.[7] His father, also named John, was a planter in St. Andrew’s Parish who moved his family to urban Charleston in the mid-1740s. Around that time, the elder Champneys became Deputy Secretary of South Carolina and held that prestigious office until his death in 1750.[8] The younger John Champneys began fulfilling his legally-mandated service in the South Carolina militia in 1760, at the age of 16, mustering with his Anglo-American peers in the Charles Town Regiment six times a year.[9] The teenager was by that time serving an apprenticeship with a prosperous local merchant, Ebenezer Simmons Jr., who had inherited from his own father a valuable wharf located due east of a brick building at the east end of Broad Street known as the Watch House and Council Chamber (now the site of the Old Exchange Building). Simmons’s property also included a swath of land immediately south of the old Watch House, stretching from modern Exchange Street nearly one hundred feet south towards the eastward extension of Elliott Street, and from the brick curtain wall on the east side of East Bay Street to the channel of the Cooper River. This extensive waterfront property, covered with eleven one-story wooden structures built in compliance with the legislative restrictions of 1736 and 1738, was arguably the most central and advantageous location for maritime business in colonial Charleston.[10]

At age nineteen, John Champneys formed a commercial co-partnership with merchant William Livingston, called Livingston, Champneys, & Co., and rented Simmons’s Wharf from his retiring mentor. A few weeks later, in November 1763, Champneys married his business partner’s teenage daughter, Ann Livingston.[11] Five years later, in June 1768, Champneys purchased Simmons’s Wharf for the large sum of £25,000 South Carolina currency (approximately £3571 sterling) by promising to make five annual mortgage payments of £5000 currency to Simmons.[12] The partnership of Livingston and Champneys expired in September 1768, when the twenty-four-year-old junior partner announced that he was embarking on a solo career as a factor and wharf owner in his own name.[13]

The factor’s business might be unfamiliar to modern audiences, but it was once a very important part of the plantation economy in the Lowcountry of South Carolina. In a very helpful advertisement published in November 1769, Champneys explained that he had at his disposal a number of schooners of various sizes, and planters wishing to dispose of their crops could summon one of his vessels to ferry their produce from the plantation to Champneys’ Wharf, where he would transfer it to a larger ship bound for Europe and to market. In short, he was the logistical middle-man between the plantation producer and the trans-Atlantic merchants who sold the crop.[14]

The commercial rise of John Champneys suffered a major setback on Christmas Day 1770. That afternoon, one of the wooden storehouses on Champneys’ Wharf, occupied as a merchant’s “compting-room” and a shoemaker’s residence, caught fire and burned to the ground. Winds from the northwest prevented the flames from engulfing the nearby Exchange building, then under construction on the site of the old Watch House, but the fire spread southward and charred nearly every other structure belonging to Champneys and his neighbors.[15] Days later, Lieutenant Governor William Bull unsuccessfully lobbied the South Carolina legislature to consider imposing even stronger restrictions on the size and nature of buildings erected to the eastward of the town’s waterfront curtain line.[16]

To repair his damaged wharf in 1771, Champneys mortgaged the entire property to the executors of the estate of the Benjamin Smith (1717–1770) in order to secure a loan of £23,400 currency.[17] John applied £10,000 of this loan to satisfy his 1768 mortgage to Ebenezer Simmons, then spent the remaining funds on new construction. Three years later, in mid-1774, Champneys boasted that his refurbished wharf extended eighty feet farther into the Cooper River and contained twenty-nine buildings, including twelve new brick stores and two wooden ones beyond the original eleven that were repaired after the fire of 1770, all of which were built in compliance with the legislative restrictions of 1736 and 1738.[18]

The repair and expansion of Champneys’ Wharf represented a major investment to grow future profits, but the work depleted John’s resources in the short term. To generate cash in May 1774, Champneys offered to sell part of his property located immediately south of the new Exchange building, a rectangular block measuring 100 feet, north to south, by 242 feet, east to west.[19] When that offer failed to generate revenue, John carved a small street through the eastern portion of the land and advertised to sell a much smaller parcel, described in the following words: “A lot of land fronting on the Bay [Street] of Charles-Town, containing 97 feet [north to south], and 25 in breadth, being the very best situation for a store or stores in town, having a front on said Bay[,] on a street running parallel with the Exchange [i.e., Exchange Street], and one street to the eastward of said lot.”

The vacant property John described in December 1774 is the present site of the four brick stores identified as 114–120 East Bay Street, which had been part of the curtain-wall moat that was filled ten years earlier. To attract a buyer, Champneys offered some misleading advice to potential investors: “The purchaser of this lot need not be under any apprehension of not being permitted to build thereon, as the tenor of the original grant and all the titles since, from my predecessors, have no restriction.”[20] While he correctly noted that the original land grant of 1698 and subsequent deeds contained no building restrictions, Champneys perhaps showed his contempt for the statute of 1738 that clearly prohibited the erection of any buildings within fifty feet of the curtain wall. Champneys’ neighbors must have seen the error of his promotional claims, and the lot remained unsold through the winter of 1774–75. In the meantime, John gained some liquidity by bringing in two partners—Daniel Stevens, his former clerk, and James Sharp, who jointly conducted business under the name Stevens, Sharp, & Co.[21]

During the initial rebellion of South Carolinians in April 1775 (see Episodes 62–64), John Champneys was among the minority of White Charlestonians who condemned what they viewed as seditious activity against the British Crown. He grudgingly signed the Articles of Association promulgated by the rebel faction that June, but only to avoid the tar-and-feathers treatment we discussed in Episode No. 236. When British and American warships traded shots in Charleston Harbor in November 1775, local leaders required all White men serving in the urban militia to perform extra guard duty. Champneys refused to participate and was fined £100. When he refused to pay, the local militia seized his carriage in late April 1776 and sold it at auction. Champneys immediately protested, noting that the militia law of South Carolina only required him to muster six times a year, which he had faithfully done since 1760.[22] Times had changed since his youth, however, and John was becoming a nuisance to his rebellious neighbors.

The arrival of a squadron of British warships outside Charleston Harbor in early June 1776 signaled a coming battle for control of Charleston. On the 9th of June, the South Carolina military, under command of General Charles Lee, ordered the removal of numerous buildings standing on the wharves of Charleston in order to raise gun batteries to defend the town. While many of the buildings belonging to rebels were merely unroofed or cut down to a lower height, those belonging to British loyalists were purposefully obliterated. Laborers scraped twenty-nine stores and two scale houses from Champneys’ Wharf to make room for a hastily-constructed gun battery made of palmetto logs and earth.[23]

American defenders on Sullivan’s Island managed to prevent the British warships from attacking Charleston on 28 June 1776, but the injured squadron lingered near the bar of the harbor for several subsequent days. To prevent any secret communication between the British mariners and loyalists in town, American soldiers in Charleston arrested John Champneys and others on June 29th and confined them within the Guard House at the southwest corner of Broad and Meeting Streets. Champneys and his loyalist neighbors pledged to keep the peace, but local leaders dispatched them on foot and under guard to Georgetown District jail in late July. Two weeks later, they were marched westward to the more remote district jail at Cheraw. The prisoners marched back to Charleston with a military escort in January 1777, when Champneys learned that his only son had died during his absence. After refusing to pledge allegiance to the state and forsake the British Crown that February, John was given sixty days to settle his affairs, while still in jail, before being banished from the state. Sales of his personal property took place in March and April, and he was released from jail on April 17th. Champneys immediately boarded a ship bound for France with his wife, two daughters, and one enslaved servant.[24]

After reaching London several months later, John Champneys published a pamphlet in early 1778 describing his “sufferings and persecution . . . for his refusal to take up arms in defence of the arbitrary proceedings carried on by the rulers” of South Carolina. He felt confident that the British military would soon suppress the American rebellion, and sought to be restart his colonial business as soon as the fighting stopped. The entire Champneys family embarked in late November 1779 for Savannah, then in British hands, but their ship was captured at sea by American forces, then recaptured by the British Royal Navy and taken to Bermuda in April 1780. A few weeks after their arrival, Mrs. Ann Champneys died at the age of thirty-four. Shortly after that tragedy, news arrived that British forces had taken possession of Charleston on the 12th of May. John embarked from Bermuda for South Carolina with his two daughters that July, but their vessel was again captured by an American ship and taken to Philadelphia. During four months’ imprisonment there, another Champneys child died. John was soon exchanged for an American prisoner and sent to British-held New York, from which he embarked with his only surviving daughter and arrived in Charleston in December 1780.[25]

In the capital of South Carolina, Champneys found his extensive wharf property “in ruin” and worked to resuscitate his commercial business. Like the other loyalists and English merchants who flocked to the port town at the time, he assumed that Charleston would remain in British hands forever, and the war for American independence would henceforth be confined to the northward. Five months after his arrival, in May 1781, Champneys agreed to lease part of his wharf to several resident merchants for a period of seven years at a moderate rent in exchange for a cash advance. He then hired a contractor to remove part of the American fortifications raised in 1776 and to erect a row or range of four brick stores along the southwestern edge of his wharf property. Each of the two-story units measured just over twelve feet wide and twenty-three feet long, with commercial space downstairs and modest living quarters upstairs. The 93-foot-long building covered nearly every inch of the vacant swath of land adjacent to the curtain wall that Champneys had advertised for sale in December 1774.[26]

Champneys’ Row, as it soon became known, was completed in the autumn of 1781, and the owner began collecting rent from four commercial tenants that December.[27] The structure cost £1,800 sterling to build, the bulk of which John financed by mortgaging the property to local house carpenter James Cook, who likely acted as the general contractor for the project. The two-year mortgage to Mr. Cook included both the brick row and a private street immediately to the east, twenty feet wide, and their agreement provides the names of the original tenants.[28]

The completion of Champneys’ Row in late 1781 was the first step toward the recovery of John’s business career, but it coincided with a dramatic turn in the War of Independence. American and French forces broke the spine of the British military at Yorktown, Virginia, that October, and it soon became obvious that British forces would eventually withdraw from American soil. While urban Charleston remained under the control of occupying forces for another year, the South Carolina General Assembly convened at nearby Jacksonboro in January 1782 for the first time in two years. Among the legislature’s first priorities was to compile a list of loyalists whose opposition to American independence during the previous six years merited retribution.

John Champneys might have hoped to be excluded from official state reprisal because he had married a widow from a well-known rebel family, Mary Harvey Wilson, in August 1781.[29] Despite such marital bonds, the legislature counted him among the state’s most offensive persons in a list of 238 loyalists compiled in early 1782. That February, the General Assembly at Jacksonboro ratified a law that became known as the “Confiscation Act,” which appointed a board of commissioners to seize the property of the most obnoxious loyalists as soon as British forces evacuated Charleston. Their “forfeited estates” were to be sold to raise money for the state treasury, and the loyalists themselves were to be banished from South Carolina.[30]

As the British forces occupying Charleston commenced preparations for departure in the autumn of 1782, John feared that his life would be in danger if he lingered in Charleston. He had been banished from South Carolina in 1777, and a state law ratified at that time warned that exiles who returned would suffer death for treason.[31] Champneys collected rent from his four tenants in early December 1782, then gathered his wife and only daughter for another journey. Elements of the British Army and Royal Navy evacuated Charleston during the second week of December 1782, accompanied by thousands of enslaved people of African descent and White loyalists (see Episodes No. 44 and No. 45). Among these were the Champneys family, who sailed from Charleston to a new home in St. Augustine, Florida.

Liverpool merchant Robert Norris, one of the original tenants of Champneys’ Row, was among a number of British subjects who did not leave South Carolina during the mass evacuation of December 1782. He occupied his rented store, he later said, “until a few weeks after the evacuation of Charlestown[,] when I was dispossessed of it by the American Commissioners of Forfeited Estates.” In early 1783, agents of the commissioners appointed by the state government confiscated Champneys’ property, ejected his tenants, and rented the valuable commercial space to local merchants loyal to the United States of America.[32]

While the four brick stores within Champneys’ Row were well-suited for maritime commerce and produced needed revenue for the nascent state government, some residents of liberated Charleston regarded the building as an unacceptable eyesore. Their objections arose not from perceived architectural deficiencies, but rather from its geographic placement. At that moment in 1783, the slender, two-story brick building was a conspicuous anomaly on the landscape of urban Charleston. Besides the prominent and ornamental Exchange, Champneys’ Row was the only civilian edifice abutting the old curtain wall on the east side of East Bay Street. Its height and placement clearly violated the provincial statutes of 1736 and 1738 that had prevented generations of wharf owners from building similar structures. Furthermore, the illegal building was the work of an infamous loyalist who had repeatedly voiced his contempt for the cause of American independence. For these combined offenses, a campaign soon commenced to demolish Champneys’ Row while its putative owner remained in exile.

In early June 1783, a grand jury convened in Charleston submitted a list of public grievances to the district court of General Sessions. Among them was a complaint from nine anonymous citizens, who requested “to have the range of buildings lately erected by Mr. John Champneys, on the curtain line, taken down, in compliance with the law, as they threaten the utmost danger, in case of fire, to the Exchange and other adjacent buildings.”[33] The Commissioners of Fortifications, a body appointed by the state legislature to superintend the defensive works in Charleston, immediately published a public notice directed “to the owners of four new brick stores, lately built on the curtain line, near the Exchange, that unless they are taken down by the 4th day of July next, they will then be removed as the law directs.”[34]

We’ve reached the mid-way point in the long narrative of John Champneys and his controversial row, and this seems like a fitting place for an intermission. Join me next week for the conclusion of this dramatic true story, when the return of the banished merchant leads to threats, groveling, damages, and restoration. John Champneys is now long dead, but his row bears the scars of their troubled past.

[1] Charleston Evening Post, 16 February 1928, page 2–A, “Taverns and Coffee Houses of Old Charleston.” Willis published at least twenty history-themed articles in the Evening Post between 1926 and 1928, all of which contain material of questionable veracity.

[2] J. H. Harris announced that he had leased Edward McCrady former stand in Charleston City Gazette, 7 November 1792, page 3.

[3] News and Courier, 20 April 1942, page 10, “Do you Know your Charleston? Coates Row.”

[4] News and Courier, 10 March 1969, page 11, “Tavern had active role in life of old Charleston,” by W. H. J. Thomas.

[5] Jonathan Poston, ed., The Buildings of Charleston: A Guide to the City’s Architecture (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997), 108–9.

[6] See the legislative report on the wharves in South Carolina Gazette (hereafter SCG), 16 May 1743, pages 1–2; section VII of Act No. 729, “An Act for imposing an additional duty of six pence per gallon on Rum imported . . . for defraying the expence of the works by this Act directed to be immediately carried on for the defence of Charlestown,” ratified on 25 May 1745, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 3 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1838), 653–56.

[7] Champneys described himself as a native of Charleston in An Account of the Sufferings and Persecution of John Champneys, A Native of Charles-Town, South-Carolina; Inflicted by Order of Congress, For his Refusal to take up Arms in Defence of the Arbitrary Proceedings Carried on by the Rulers of Said Place. Together with his Protest, &c. (London: n.p., 1778), and in Champneys’ memorial and supporting papers, 1786–88, presented to the British commissioners investigating the claims of American loyalists, now held by the National Archives, Kew, AO 12/50/269, which were transcribed by the New York Public Library (hereafter NYPL), American Loyalist Collection, 1777–1790, transcript volume 55, pages 373–96, and are available at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH) on micro reel RW3168.

[8] Walter B. Edgard and N. Louise Bailey, eds., Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives, volume 2 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1977), 151.

[9] Champneys mentioned his militia service in Champneys, An Account of the Sufferings, 2.

[10] Champneys identified himself as “clerk to Mr. Simmons before he purchased this” wharf in 1768, and described the buildings standing on it at that time in NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 382.

[11] SCG, 15–22 October 1763, page 3, “Livingston, Champneys, & Co.”; [Mabel Webber, ed.], “Records Kept by Colonel Isaac Hayne,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 11 (January 1910): 27.

[12] Ebenezer Simmons and Jane, his wife, to John Champneys, lease and release, 1–2 June 1768, Charleston County Register of Deeds (hereafter CCRD), book K3: 224–32; John Champneys and Ann, his wife, to Ebenezer Simmons, mortgage by lease and release, 3–4 June 1768, CCRD K3: 232–39.

[13] SCG, 19 September 1768, page 3.

[14] SCG, 23 November 1769, page 2.

[15] See the local news in South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, 25 December 1770, page 2; South Carolina and American General Gazette, 31 December 1770–7 January 1771, page 3.

[16] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, No. 38, part 3, page 458 (16 January 1771).

[17] John Champneys and Ann, his wife, to Thomas Smith, Thomas Loughton Smith, and Isaac Motte, acting executors of the will of Benjamin Smith, mortgage by lease and release, 17–18 September 1771, CCRD X3: 6–13. According to a receipt recorded between pages 235–36 of his abovementioned 1768 mortgage, Champneys made his final payment of £10,000 to Simmons on 17 September 1771.

[18] Champneys obtained a grant of a low-water lot to the east of his wharf on 4 December 1771; see SCDAH, Colonial Land Grants (copy series), volume 43, page 429. Champneys described his wharf and buildings, “as valued 1st Augt. 1774,” in NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 378, 382.

[19] South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, 3 May 1774, page 2; SCG, 26 December 1774, page 2.

[20] SCG, 26 December 1774, page 2. William Elliott received a grant for the land in question on 15 July 1698.

[21] SCG, 12 September 1774, page 4.

[22] Champneys, An Account of the Sufferings, 2–3.

[23] See the statements of Champneys, James Carsan, and Robert Norris in NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 375, 386, 394.

[24] Champneys, An Account of the Sufferings, 4–20.

[25] Champneys described these events in NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 373–74, 381; Ann’s death was also reported in South Carolina and American General Gazette, 9 December 1780, page 2.

[26] See the testimony of John Champneys, John Denniston, and Robert Norris in NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 374, 383, 388–89, 394–95.

[27] NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 378; 383–84.

[28] John Champneys, gentleman, and Mary, his wife, to James Cook, house carpenter, mortgage by lease and release, 1–2 February 1782, CCRD T5: 370–72. The original tenants were four mercantile firms: Currie and Norris, John Denniston and Company, Lawson and Price, and Johnston and Mitchell.

[29] D. E. Huger Smith and A. S. Salley, eds., Register of St. Philip’s Parish, Charles Town, or Charleston, S.C. 1754–1810 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1971), 212.

[30] Act No. 1153, “An Act for disposing of certain estates, and banishing certain persons therein mentioned,” ratified on 26 February 1782, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 4 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1838), 516–23.

[31] See “An Ordinance for establishing an oath of abjuration and allegiance,” ratified on 13 February 1777, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 1 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnson, 1836), 135–36; in NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 374, Champneys stated that he was “liable to suffer death” because of the 1777 law.

[32] NYPL, American Loyalist Collection, 55: 394–95.

[33] South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, 10 June 1783, page 4. The grand jury was empaneled on 3 June.

[34] South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, 7 June 1783, page 1.

NEXT: John Champneys and His Controversial Row, Part 2

PREVIOUSLY: Bathing to Beat the Heat in Early Charleston, Part 2

See more from Charleston Time Machine