Hucksters’ Paradise: Mobile Food in Urban Charleston, Part 1

Processing Request

Processing Request

Vending food on the streets of Charleston was a major form of commerce for centuries before it all but disappeared in the mid-twentieth century. Mobile and musical hucksters, predominantly of African descent, carried food around the city in baskets and carts from the earliest day of Carolina, serving an important but forgotten niche market in the local culinary scene. To trace their enduring influence on local culture and commerce, we’ll wind our time machine back to the roots of the hucksters and chart their rise into Antebellum days.

“Huckster” is an ancient English word endowed with a variety of meanings. Here in the twenty-first century, it’s generally used in a negative context, as in “a huckster salesman” or “a huckster politician.” By these phrases we mean to indicate an unscrupulous person who attempts to deceive by representing a defective product or an adverse situation in facetiously positive terms. In earlier centuries, however, the term “huckster” (occasionally spelled “huxter”) carried a broader range of meanings. Samuel Johnson’s acclaimed Dictionary of the English Language (London, 1755; third edition, Dublin, 1768), for example, acknowledged this negative connotation by describing a huckster as “a trickish mean fellow,” but noted that such was the term’s secondary definition. To Johnson and most of the English-speaking world in the eighteenth century, a huckster was primarily “one who sells goods by retail, or in small quantities.” The verb “to huckster,” according to Dr. Johnson, meant simply “to deal in petty bargains.”[1]

In the general chain of historic commerce, leading from manufacturer to customer or from farm to table, hucksters purchased their stock-in-trade directly from the producers. When making such bulk or “wholesale” purchases, they often negotiated or haggled over the price of the goods in question. Some species of hucksters continued this price haggling when they re-sold or “retailed” those goods in smaller parcels to individual customers. By these practices, the terms “huckster” and “huckstering” became synonymous with a relatively informal sort of commerce. Hucksters in centuries past were known to operate small shops, booths, or stands that were often temporary in nature. The term was also applied to mobile retailers of various commodities who carried their stock on their person as they perambulated through the streets on foot or pushed a hand-cart or pulled a small wagon. In this latter sense, door-to-door salesmen in the nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries were sometimes called hucksters. As retail practices evolved and gentrified over time, savvy customers began to view these antiquated, informal methods of sales with increasing derision.

In the general chain of historic commerce, leading from manufacturer to customer or from farm to table, hucksters purchased their stock-in-trade directly from the producers. When making such bulk or “wholesale” purchases, they often negotiated or haggled over the price of the goods in question. Some species of hucksters continued this price haggling when they re-sold or “retailed” those goods in smaller parcels to individual customers. By these practices, the terms “huckster” and “huckstering” became synonymous with a relatively informal sort of commerce. Hucksters in centuries past were known to operate small shops, booths, or stands that were often temporary in nature. The term was also applied to mobile retailers of various commodities who carried their stock on their person as they perambulated through the streets on foot or pushed a hand-cart or pulled a small wagon. In this latter sense, door-to-door salesmen in the nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries were sometimes called hucksters. As retail practices evolved and gentrified over time, savvy customers began to view these antiquated, informal methods of sales with increasing derision.

All of the ancient commercial practices I’ve just described have continued in one form or another into the twenty-first century, but we no longer apply the now-pejorative term “huckster” to them. Girls pushing Italian-ice carts through the streets of summertime Charleston, for example, or an ice-cream truck jangling through a suburban neighborhood, or a man hawking peanuts on the side of the road, or a young man selling palmetto roses to tourists, or a food truck selling tacos in a parking lot—they’re are all modern-day hucksters, in the historical sense of the word, but we don’t address them as such anymore. Nevertheless, they are all part of a long, unbroken tradition of huckstering that dates back to the temporal roots of this community.

For the purposes of this program, I’m limiting my investigation to one specific aspect of the huckstering business in early Charleston; namely, the ambulatory or mobile sales of various food stuffs. This appetizing activity dominated the huckstering trade in this city, but some mobile hawkers sold other small goods or “truck.” We’ll dismiss, for the moment, the colorful ranks of wandering flower ladies, pencil pushers, fowl vendors, match boys, scissor grinders, ballad singers, wood sawyers, chimney sweeps, and rag collectors that once plied our streets. Within the sphere of ambulatory food commerce in early Charleston, we can make a further division between the retailers of raw items like fresh fish, shrimp, crab, oysters, vegetables, and fruit, and the vendors of prepared foods like cakes, cooked rice, boiled peanuts, ice cream, and other ready-to-eat snacks. Each of these two branches is characterized by distinct practices and personalities, but their histories are so similar and intermingled that it’s really impossible to talk about one without including the other.

The practice of huckstering food came to Charleston in the 1670s as part of the cultural baggage brought here by the early settlers of the Carolina colony—white and black. Huckstering, by its very nature, is primarily an urban phenomenon, but it is not exclusively a European one. Practiced by civilizations around the world under a variety of names, huckstering has existed for millennia wherever people settled in close proximity and their collective labors became divided into different trades and specialties. The simple concept of purchasing a small stock of perishable goods from a farmer or fisherman and then hawking or peddling that stock to customers generally involves little skill or training and limited monetary investment. It does, however, demand a great deal of energy and perseverance. The additional task of transforming raw foods into something like a simple cake requires a few additional resources, but the necessary investment is usually minimal and often improvisatory.

I know of no surviving records that document the business of selling or even bartering food in earliest days of Charles Towne on the west bank of the Ashley River, now Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site. The early Carolina settlers clearly grew provisions, prepared dishes, and ate regular meals, of course, but we have very little written evidence of the local food trade during the first few decades of the colony. People living in and around Albemarle Point in the 1670s undoubtedly traded provisions like corn, peas, and potatoes, while others brought fish and other fresh seafood to the inhabitants of the nascent town. That activity continued when Charles Town transferred to its present site in the spring of 1680, but, again, we have very little record of the practical realities related to the food trade.

We do know, however, that problems arose in the 1680s from the prevalence a sort of transaction described as “indirect bargains” between free citizens and the town’s small population of white indentured servants and enslaved Africans. Some “evilly disposed” servants were engaging in private sales with free men and women, selling small goods that technically did not belong to them. By embezzling and selling without permission their masters’ goods—whether provision foods or otherwise—the servants were impoverishing the free population and nourishing a pernicious form of vice. South Carolina’s provincial government sought to eradicate this problem by ratifying a law in late February 1687 “inhibiting the trading with servants or slaves.” From that point forward in our community’s history, through a long series of legislative revisions and extensions, it became illegal for servants—whether indentured or enslaved—to offer any goods for sale unless said servants possessed some sort of note, ticket, badge, or license acknowledging they had received permission to do so.[2]

The 1687 law to restrict “indirect bargains” provides the earliest-known snapshot of a market scenario that endured on the streets of Charleston for three hundred years: People of the lowest socio-economic class carried on a relatively informal but officially-regulated trade in small goods with more affluent customers on the city streets. As the number of white indentured servants in Charleston declined around the turn of the eighteenth century and enslaved Africans formed the majority of the local population by 1708, this informal street trade, or huckstering, became a predominately black phenomenon. That racial characteristic distinguished Charleston’s early huckstering trade from contemporary cities like London, Paris, Boston, and Philadelphia, for example, but the urban centers of other slave-holding colonies like Barbados, Jamaica, Saint-Domingue, and Louisiana were similarly dominated by enslaved black hucksters. Segregated and regulated by law and custom, the black men, women, and children who plied the streets of Charleston hawking food and other goods established a culture unique to themselves and to this community. Their activities coalesced into patterns and customs that eventually formed one of the city’s most distinctive characteristics, and one that captured the imagination of many a visitor over the centuries.

The 1687 law to restrict “indirect bargains” provides the earliest-known snapshot of a market scenario that endured on the streets of Charleston for three hundred years: People of the lowest socio-economic class carried on a relatively informal but officially-regulated trade in small goods with more affluent customers on the city streets. As the number of white indentured servants in Charleston declined around the turn of the eighteenth century and enslaved Africans formed the majority of the local population by 1708, this informal street trade, or huckstering, became a predominately black phenomenon. That racial characteristic distinguished Charleston’s early huckstering trade from contemporary cities like London, Paris, Boston, and Philadelphia, for example, but the urban centers of other slave-holding colonies like Barbados, Jamaica, Saint-Domingue, and Louisiana were similarly dominated by enslaved black hucksters. Segregated and regulated by law and custom, the black men, women, and children who plied the streets of Charleston hawking food and other goods established a culture unique to themselves and to this community. Their activities coalesced into patterns and customs that eventually formed one of the city’s most distinctive characteristics, and one that captured the imagination of many a visitor over the centuries.

One could easily fill a book with the stories of Charleston’s hucksters, but my mission here is to provide a more compact overview of the topic. From the city’s roots in the late seventeenth century to the early twentieth century, their trade followed a relatively consistent pattern of activity. Charleston’s black hucksters would arise before daybreak and hurry to their preferred stations along the waterfront or to the Broad Path (King Street) to greet the three streams of food coming into Charleston every day. Canoes and other small boats ferried vegetables and fruit from the plantations and islands adjacent to the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, while fishermen and women reeled in their early-morning catch, and wagons from the countryside brought fresh vegetables and meat to town. From these three streams of wholesale provisions, individual hucksters would haggle to purchase small quantities of specific items that they could vend to customers on the streets. The bulk of the meat, vegetables, and fish brought to town every day went directly to Charleston’s designated public market place—which moved several times before it settled in present Market Street in 1807. A portion of these provisions were hawked about the street by a legion of hucksters, however, who carried baskets or trays on their heads, pushed wooden wheelbarrows and hand-carts, or pulled small wagons full of their retail stock. Some hucksters with access to cooking facilities whipped a few ingredients into simple comestibles that were easy to carry. To attract customers, all the hucksters called out their wares in a wide variety of individual cries, shouts, slogans, and songs that echoed through the town from before sunrise to beyond sunset.

As I hope you can now imagine, the people of early Charleston awoke every day to a colorful and cacophonous pageant of activity that revolved around the vending and distribution of perishable foods. Note, also, the degree to which Charleston’s food history must be intertwined with the creation and preservation of the Gullah language in these daily negotiations. Even after the advent of rudimentary refrigeration in the early nineteenth century (see Episode No. 49), most people in the city had to purchase fresh food every day in order to survive, and there were several options. One could visit the public market and purchase raw goods, or one could send a servant to the market to fetch various ingredients. The ambulatory hucksters provided an even more convenient service: Individuals selling a variety of fresh goods passed through street and neighborhoods in an early form of home delivery. If you planned to have shrimp and grits for breakfast, like most Charlestonians once did, for example, then you simply listened for one of the shrimp hucksters to pass your door and flagged him or her down. If you needed a quart of okra for an all-day stew, you waited for the familiar cry of the okra woman and purchased a supply from the basket on her head. Similarly, if you were running errands around town and fancied a quick snack, you might buy a palm-sized “pannycake,” or a piece of “ground nut” (peanut) cake, or a “tetter-poon” (sweet potato pone) from a passing huckster. Hucksters provided a valuable and convenient service to the people of Charleston, but not everyone in the community viewed their activities in such a positive light.

From the perspective of seventeenth-century English law, the huckstering business was both illegal and a contemptible affront to legitimate commerce. The provision foods coming into Charleston every day from the countryside were ostensibly destined for the town’s designated public market place, where they were to be sold according to the traditional market rules and regulations we inherited from England. The profits derived from the sale of such goods should return to the producer, who, in early South Carolina, was almost invariably a white man who owned a plantation run with enslaved labor. By arising before dawn to greet the various boats and wagons, however, the enterprising black hucksters were intercepting the food supply and creating an illegal secondary market in which they—the enslaved upstarts!—set the prices and earned slim profits for themselves. In legal terms, the hucksters engaged in forestalling, engrossing, and regrating; that is, purchasing goods before they came to a proper market, sometimes cornering the supply, and then raising the prices and re-selling them in close proximity to the very market they had by-passed. Such subversive practices discouraged customers from visiting the legitimate market stalls and thus deprived honest, law-abiding food sellers of their due custom. Forestalling, engrossing, and regrating occurred in every market community in the American colonies and elsewhere, of course, but the racial character of the huckstering trade in early Charleston drove white authorities to distraction.

As early as October 1704, Governor Nathaniel Johnson implored the South Carolina General Assembly to pass a law “to prevent forestalling and engrossing by the hucksters, and other ill-disposed persons.” The Commons House eventually appointed a committee to consider the governor’s recommendation, but nothing happened for several years.[3] When the provincial legislature finally did enact a comprehensive market statute in April 1710, they acknowledged that the lack of a such a law had heretofore “given encouragement to sundry evil disposed and covetous persons as to incite them to put in practice the most abominable and scandalous projects of huckstering forstalling [sic] and ingrossing [sic] which are pernicious to all [honest people].” South Carolina’s earliest-surviving market law required food producers to deliver or send their provisions directly to the designated public market (then at the east end of Broad Street) and nowhere else, and prohibited the sales of provisions of any kind outside the market or before the salaried clerk of the market had rung the bell to signal the official opening of the market at sunrise. Persons violating this law would be “reputed and taken as a huckster,” and the clerk of the market was empowered to obtain a warrant from a Justice of the Peace to seize his or her illegal stock.[4]

Although the South Carolina legislature was clearly angry about the practice of huckstering, the mechanism enacted in 1710 to prevent such practices was too cumbersome to be effective. It required a degree of vigilance and industry that the successive clerks of the market simply could not muster. As the years passed, public complaints about forestalling, engrossing, and regrating in the market continued, and the provincial government periodically revised the market laws in the attempt to prevent such activity. In the spring of 1736, for example, the provincial assembly created a volunteer board of Commissioners of the Markets to oversee local food sales and to assist the paid clerk.[5] Their collective inactivity did little to amend the problem, and persistent complaints led to further regulation. A law ratified in the spring of 1751 instituted a system of annual badges or licenses intended to tax and regulate the activities of enslaved laborers and porters working on the streets of urban Charleston. Since huckstering was illegal, however, the city’s first badge law ignored the daily throngs of enslaved people selling food and other goods on the streets.[6]

Although the South Carolina legislature was clearly angry about the practice of huckstering, the mechanism enacted in 1710 to prevent such practices was too cumbersome to be effective. It required a degree of vigilance and industry that the successive clerks of the market simply could not muster. As the years passed, public complaints about forestalling, engrossing, and regrating in the market continued, and the provincial government periodically revised the market laws in the attempt to prevent such activity. In the spring of 1736, for example, the provincial assembly created a volunteer board of Commissioners of the Markets to oversee local food sales and to assist the paid clerk.[5] Their collective inactivity did little to amend the problem, and persistent complaints led to further regulation. A law ratified in the spring of 1751 instituted a system of annual badges or licenses intended to tax and regulate the activities of enslaved laborers and porters working on the streets of urban Charleston. Since huckstering was illegal, however, the city’s first badge law ignored the daily throngs of enslaved people selling food and other goods on the streets.[6]

The sustained nature of this problem suggests, of course, that early-rising hucksters who purchased provisions and hawked them through the streets were finding ready customers who kept them in business. In a classic example of simple economics, the hucksters thrived by supplying a constant demand, while the law trailed behind the social custom. As I mentioned earlier, it appears that this local legal conundrum was fueled by the racial politics of the day. To my knowledge, all of the documented grievances against illegal huckstering in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Charleston point to enslaved people and free people of color. I’ll mention a few colonial-era examples to illustrate my point.

In March of 1734, a grand jury presented to the local courts, “as a very great grievance and an intollerable [sic] hardship on the several inhabitants of Charles Town, that Negroes are suffered to buy and sell, and be hucksters of corn, pease [sic], fowls, &c. whereby they watch night and day on the several wharfes [sic], and buy up many articles necessary for the support of the inhabitants, and make them pay an exorbitant price for the same.”[7] A number of poor white vendors submitted a petition to the provincial legislature in the spring of 1747 complaining about “the great liberty and indulgence which is given to Negroes and other slaves in Charles Town to buy, sell, and vend” such commodities as earthen ware, fruit, bread, onions, apples, tobacco, eggs, and other things.[8] Another grand jury in April 1771 complained “that Negro wenches, and other slaves, are allowed to huckster and sell all sorts of dry goods, fruit and victuals, about the markets and streets, which is often an inducement to theft, it being well known that they are ready to buy and receive such as are stolen.”[9] In May 1773, a grand jury stated “that the huckstering and selling [of] dry goods, cooked rice, and other victuals, is still practiced about the markets and streets of Charles-Town, by Negroes; whose supply for carrying on their trade is from theft or unfair purchases, and hath this great evil arising from it, that [the] run-away slaves of Charles-Town, and [the] country, are subsisted daily thereby.”[10] Finally, in June 1775, a grand jury pointed to the “general supineness [sic] and inactivity in the majistrates [sic] and others, whose duty it is to carry the Negro Acts into execution,” and asked the legislature to amend various laws “so as to prevent slaves being suffered to cook, bake, sell fruits, dry goods, and otherwise traffick [sic], barter, &c. in the public markets and streets of Charles-Town, and by those means preventing many poor and industrious families from obtaining an honest livelihood.”[11]

The legislative act to incorporate the City of Charleston in August 1783 transferred the duties of the old Commissioners of the Markets to the new City Council. The city’s first market ordinance, ratified in October 1786, instituted a new board of market commissioners and followed the general outline of the colonial-era laws with little innovation.[12] As the local economy gradually strengthened in the years immediately after the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), the practice of huckstering quickly resumed after a period of apparent wartime hibernation. A correspondent calling himself “Civis” in July 1788 was convinced that huckstering had never occurred in Charleston before American independence, and castigated the new City Council for failing “to put a final stop to this huxtering business carried on by free negroes & slaves.” “If the swarm of female huxtering slaves was sent to work, there would be bread for a number of poor people; but at present these wretches will not suffer a white person to sit in the market to sell fruit, ginger bread, nuts, &c. Perhaps some will say, how is this evil to be remedied[?]—why, let no slaves sell any thing but the produce of their owners [sic] plantations or gardens; this will put a total stop to a useless, shameful gang of thieves and receivers.”[13]

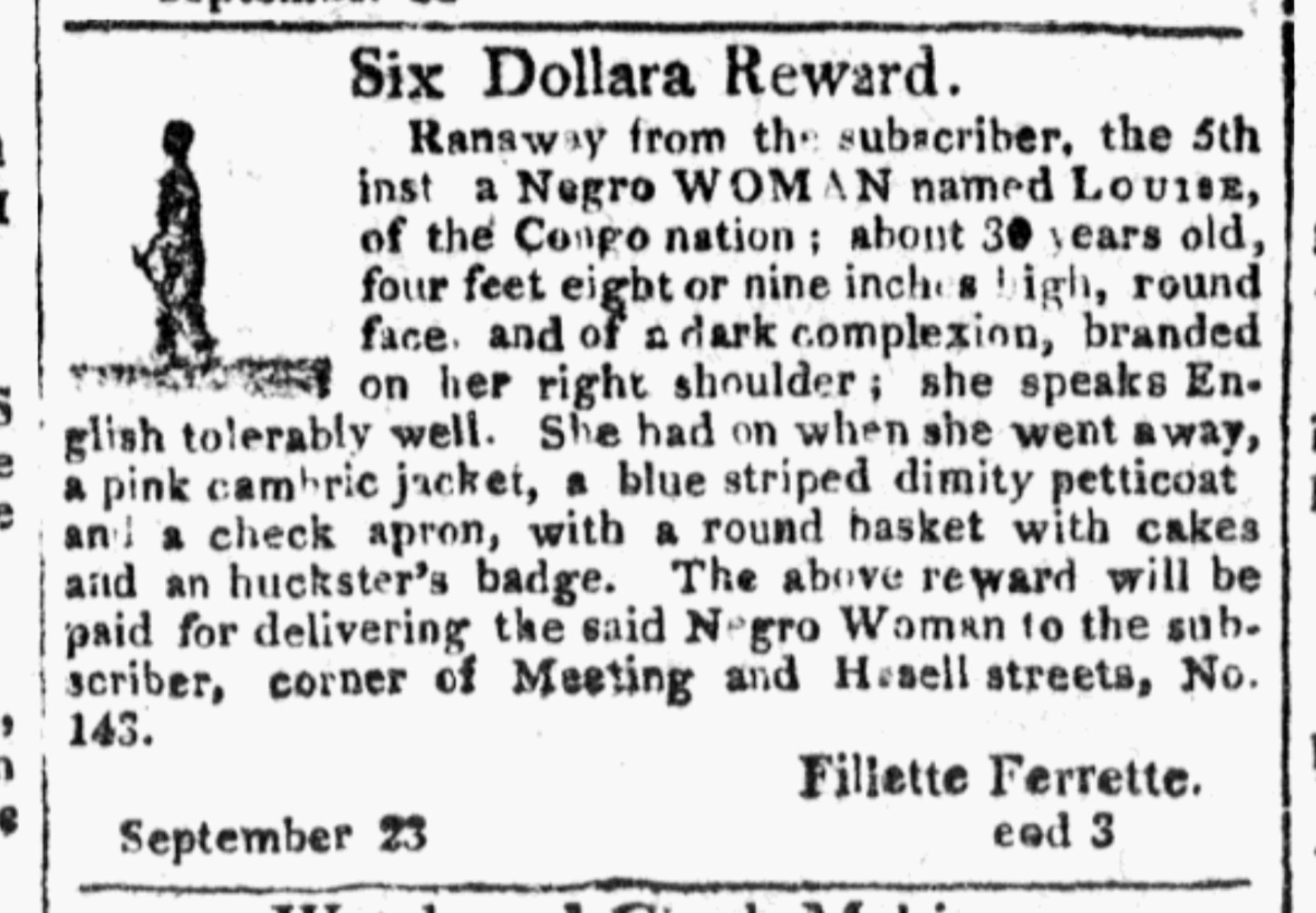

During the closing years of the eighteenth century, Charleston’s municipal government periodically published reminders to ensure that the public understood the distinction between legal marketing and illegal huckstering.[14] Old habits die hard, however, especially when fueled by the zeal of an oppressed people to engage in a bit of private enterprise. At last, in the summer of 1800, the City Council ended the century-long local war against huckstering and adopted a new policy. In the context of a revised ordinance “for the better regulation of slaves,” city leaders decided to tax the practice of huckstering rather than continue their futile attempts to chase it from the streets. From July of 1800 to the end of the Civil War, enslaved men and women working as hucksters within the corporate limits of Charleston were required to purchase annually and wear constantly a stamped metal badge identifying their now-legitimate occupation. A similar annual badge for a fisherman or washerwoman cost one dollar in 1800, two dollars for a porter or drayman’s badge, and three dollars for badge to identify an enslaved “handicraft tradesman.” Hucksters, however, had to pay six dollars each year for their badge. From this graduated price schedule, we can deduce that the City Council still wanted to discourage a stream of commerce that it had long failed to eradicate.[15] Finding that discouragement insufficient, in October 1806 the city raised the price of the huckster’s badge to fifteen dollars.[16] That “exorbitant” increase was found to “defeat the intention” of original ordinance, so in February 1813 the city reduced the price to five dollars, where it remained until the final days of the Civil War in 1865.[17]

The City of Charleston’s effort to regulate the practice of huckstering by requiring an annual badge or license was really a compromise decision. The law condoning the sale of badges to huckster required them to sell only such that they had produced or cultivated themselves, or goods belonging to their respective masters and sold with their permission. The ancient prohibition against forestalling other provisions streaming into town every morning continued to be enforced, and enforced poorly. In July 1809, for example, an anonymous citizen asked city leaders “to exterminate the abominable practice of huxtering and forestalling, which now prevails in the city, to a most pernicious extent.” After purchasing certain foods before the market officially opened, said the correspondent, the hucksters then raised the prices on such items by at least twenty-five percent. “And where does this 25 per cent. go? Into the pockets of the master of the huxter? (For it is well known that all the huxters are negro slaves.) No! It all goes into the pockets of these huxters, and enables them to live in a style of ease and comfort extremely injurious to their masters. The other servants that are retained in the houses of their masters for domestic purposes, seeing the ease and comfort, and, I may add, the luxury in which their fellow servants, the huxters and huxtresses live in, become discontented, and consequently disobedient.”[18]

The City of Charleston’s effort to regulate the practice of huckstering by requiring an annual badge or license was really a compromise decision. The law condoning the sale of badges to huckster required them to sell only such that they had produced or cultivated themselves, or goods belonging to their respective masters and sold with their permission. The ancient prohibition against forestalling other provisions streaming into town every morning continued to be enforced, and enforced poorly. In July 1809, for example, an anonymous citizen asked city leaders “to exterminate the abominable practice of huxtering and forestalling, which now prevails in the city, to a most pernicious extent.” After purchasing certain foods before the market officially opened, said the correspondent, the hucksters then raised the prices on such items by at least twenty-five percent. “And where does this 25 per cent. go? Into the pockets of the master of the huxter? (For it is well known that all the huxters are negro slaves.) No! It all goes into the pockets of these huxters, and enables them to live in a style of ease and comfort extremely injurious to their masters. The other servants that are retained in the houses of their masters for domestic purposes, seeing the ease and comfort, and, I may add, the luxury in which their fellow servants, the huxters and huxtresses live in, become discontented, and consequently disobedient.”[18]

Periodic complaints about disobedient Negro hucksters continued to appear in the newspapers and City Council proceedings of Antebellum Charleston, and white sensibilities were heightened by the tumultuous Denmark Vesey Affair of 1822. The ambulatory food sellers were numerous and their practices something of an institution, but some members of the white community wished to throttle their potentially subversive voices. In March of 1823, for example, a letter to the editor from “A Warning Voice” argued that “the legalized audacity of the negros who hawk their wares, &c. about our streets, should no longer be permitted. . . . The[ir] public cries should be regulated. The negro should be taught to announce what he has to sell and to suppress his wit. A decency and humility of conduct should pervade all ranks of our colored population.”[19] Later that same year, a white visitor to Charleston penned a highly sarcastic note to the local newspaper describing the cacophony of sounds heard in the city every night and early morning. By the time the sun rose, said the drowsy visitor, “the street was alive, and so many odd and unintelligible cries from honest milk-wenches, radish merchants, cake sellers, venders of green corn, cucumbers and water-melons, were resounding in every quarter, that I gave up sleep as impracticable, and rose from bed.”[20]

Mid-nineteenth-century Charleston was not the only city teeming with a multitude of wandering street sellers, nor was it the only American city in which that trade included vendors of African descent. Enslaved men and women dominated Charleston’s huckstering trade for nearly two hundred years, however, during which time they developed a suite of unique culinary, linguistic, and musical traditions that persisted beyond the death of slavery and into the twentieth century. In fact, Charleston experienced a sort of “golden age” of huckstering in the years after the Civil War, when the mobile vendors proliferated and their colorful habits attracted the admiration of white tourists. Next week we’ll continue this journey from post-war emancipation to the annual competition for the title of “Champion Huckster of Charleston.”

[1] Nathan Bailey’s An Universal Etymological English Dictionary, first published in London in 1721, simply defines huckster as “a seller of provisions by retail.”

[2] See Act No. 34, “An Act inhibiting the trading with servants or slaves,” ratified on 28 February 1686/7, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 2 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1837), 22–23; and Act No. 60, “An Act inhibiting the tradeing [sic] with servants and slaves,” ratified on 25 March 1691, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 2: 52–54.

[3] South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, Green’s transcription, 1702–6, page 249 (5 October 1704); A. S. Salley, ed., Journal of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina, March 6, 1705/6–April 9, 1706 (Columbia: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1937), 20–21 (11 March 1705/6).

[4] Act No. 294, “An Act to appoint and erect a market in Charles Town, for the publick sale of provisions, and against regrators, forestallers and ingrossers,” ratified on 8 April 1710. The title only of this act is included in the published Statutes at Large of South Carolina, 2: 351, but the text is found at SCDAH, in the manuscript of Nicholas Trott’s manuscript “Laws of South Carolina,” pp. 31–38.

[5] The text of Act No. 598, “An Act for Regulating the Markets in the Parish of St. Philip’s, Charles-Town, and for preventing Forestalling, Ingrossing, Regrating, and unjust Exactions in the said Town and Market,” ratified on 29 May 1736, was not included in the published Statutes at Large of South Carolina, but can be found in South Carolina General Assembly, Acts Passed by the General Assembly of South-Carolina, at a Sessions begun and holden at Charles-Town, the Fifteenth Day of November in the Seventh Year of the Reign of Our Sovereign Lord George the Second, by the Grace of God, of Great-Britain, France and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Annoque Domini One Thousand Seven Hundred and Thirty Three, And from thence continued by divers [sic] Prorogations and Adjournments to the Twenty-Ninth Day of May, One Thousand Seven Hundred and Thirty Six (Charleston, S.C.: Lewis Timothy, 1736), 25–29.

[6] The text of Act No. 787, “An additional and explanatory Act, to an Act of the General Assembly of this Province, intitled [sic], an Act for keeping the Streets in Charles-Town clean; and establishing such other Regulations for the Security, Health and Convenience of the inhabitants of the said Town, as are therein mentioned; and for establishing a new Market in the said Town,” ratified on 4 May 1751, was not included in the published Statutes at Large of South Carolina, but can be found in South Carolina General Assembly, Acts Passed by the General Assembly of South-Carolina, At a Sessions begun to be holden at Charles-Town, on Tuesday the Twenty-eighth Day of March, in the Twenty-third Year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord George the Second, by the Grace of God, of Great-Britain, France and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. and in the Year of our Lord 1749. And from thence by divers Adjournments to the 24th Day of April, 1751 (Charleston, S.C.: Peter Timothy, 1751), 12–15.

[7] South Carolina Gazette (hereafter SCG), 23–30 March 1734.

[8] J. H. Easterby and Ruth S. Green, eds. The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, September 10, 1746-June 13, 1747 (Columbia: South Carolina Archives Department, 1958), 154 (5 February 1746/7).

[9] SCG, 18 April 1771 (supplement). A nearly identical grievance appeared in the grand jury presentments published in SCG, 22 February 1773.

[10] SCG, 24 May 1773. A nearly identical grievance appeared in the grand jury presentments published in South Carolina and American General Gazette, 20–27 May 1774, and SCG, 31 October 1774.

[11] South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, 20 June 1775.

[12] “An Ordinance for the regulating and governing of the Public Markets of the City of Charleston,” ratified on 11 October 1786, in Alexander Edwards, compiler, Ordinances of the City Council of Charleston, In the State of South Carolina, Passed since the Incorporation of the City, Collected and Revised Pursuant to A Resolution of the Council. To Which Are Prefixed, the Act of the General Assembly for Incorporating the City, and the Subsequent Acts to Explain and Amend the Same (Charleston, S.C.: W. P. Young, 1802), 35–40.

[13] [Charleston] City Gazette, 15 July 1788.

[14] See, for example, the notice of the City Marshal, “To Forestallers and Hucksters,” published in City Gazette, 8 July 1799.

[15] “An Ordinance for the better regulation of slaves, and for other purposes therein mentioned,” ratified on 16 July 1800, in Edwards, Ordinances of the City Council of Charleston, 1802, 193–95.

[16] “An ordinance for the government of the negroes and other persons of color, within the City of Charleston, and for other purposes therein mentioned,” ratified on 28 October 1806, in Alexander Edwards, compiler, Ordinances of the City Council of Charleston, Passed between the 24th of September 1804, and the 1st Day of September 1807. To Which is Annexed, a Selection of Certain Acts and Resolutions of the Legislature of the State of South-Carolina, Relating to the City of Charleston. Charleston, S.C.: W. P. Young, 1807), 394.

[17] “An Ordinance to alter and amend the thirteenth section of an ordinance, entitled, ‘An ordinance for the government of the negroes and other persons of color, within the City of Charleston, and for other purposes therein mentioned,” ratified on 1 February 1813, in Charleston City Council, The Ordinances of the City Council of Charleston, South Carolina, Passed since the First of September, 1807, and to the 13th of November, 1815 (Charleston, S.C.: G. M. Bounetheau and Lewis Bryer, 1815), 533. For more information on slave badges, see Harlan Greene and Harry Hutchins, Jr., Slave Badges and the Slave-Hire System in Charleston, South Carolina, 1783–1865 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2004), 123, 136, 148, 165.

[18] [Charleston] Strength of the People, 18 July 1809, “Brazen Face.”

[19] Charleston Courier, 26 March 1823.

[20] City Gazette, 8 July 1823.

PREVIOUS: Dining and Drinking in Charleston Before the Food and Beverage Industry

NEXT: Hucksters’ Paradise: Mobile Food in Urban Charleston, Part 2

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments