The Horn Work: Marion Square’s Tabby Fortress

Processing Request

Processing Request

Have you heard the story of the Horn Work in Marion Square? You know—that mysterious, unobtrusive, lumpy slab of concrete covered with oyster shells standing in the park near King Street? Did you know it’s actually a tiny remnant of a massive fortress that once controlled access to colonial-era Charleston? And it was the city’s first citadel during the American Revolution? The Horn Work is one of Charleston’s biggest secrets hiding in plain sight, and today we’ll review the most salient chapters of its must-read story.

Marion Square is Charleston’s most popular public gathering space, but few visitors recognize one of the city’s most valuable historical treasures within the park. Behind a modest iron railing located approximately 125 feet east of King Street stands a mysterious slab of gray, concrete-like material. It stands approximately six feet high, is nearly ten feet long, and just over two feet wide at its base. A small metal plaque affixed to the railing is inscribed with a few disjointed words: “Remnant, of Horn Work. May 1780. Siege of Charleston.” This brief text, installed in 1883, has provided little to inspire the imagination of successive generations of tourists and locals, who often pass the familiar object without a second look.

The homely remnant preserved within that iron fence merits much more attention than it currently receives, however. The brief text on its humble plaque imparts little of the dramatic story behind the massive structure that once dominated the site of Marion Square between 1758 and 1784, and which formed one of the most impressive military posts of the American Revolution. The documentary trail of evidence that illuminates the rise and fall of Charleston’s forgotten Horn Work is fragmentary, incomplete, and scattered across the globe. It’s also a complex narrative, drawn out over a number of decades and embedded within a deep context of international political and military issues.

The homely remnant preserved within that iron fence merits much more attention than it currently receives, however. The brief text on its humble plaque imparts little of the dramatic story behind the massive structure that once dominated the site of Marion Square between 1758 and 1784, and which formed one of the most impressive military posts of the American Revolution. The documentary trail of evidence that illuminates the rise and fall of Charleston’s forgotten Horn Work is fragmentary, incomplete, and scattered across the globe. It’s also a complex narrative, drawn out over a number of decades and embedded within a deep context of international political and military issues.

In short, it’s a difficult story to tell in a brief synopsis. After struggling with this topic for some years, I’m going to attempt to provide an overview of the subject today, followed by a series of more detailed segments in the near future. In my experience, one of the best ways to whittle a complex topic down to a manageable size is to create a series of questions and answers that address the most salient issues. You might have heard me describe the Horn Work in recent years as “Charleston’s tabby fortress.” All of these words, drawn from the vocabulary of eighteenth-century European military engineering and the vernacular architecture of early South Carolina, might not mean anything to readers today, so let’s begin with the basics.

What is a Horn Work?

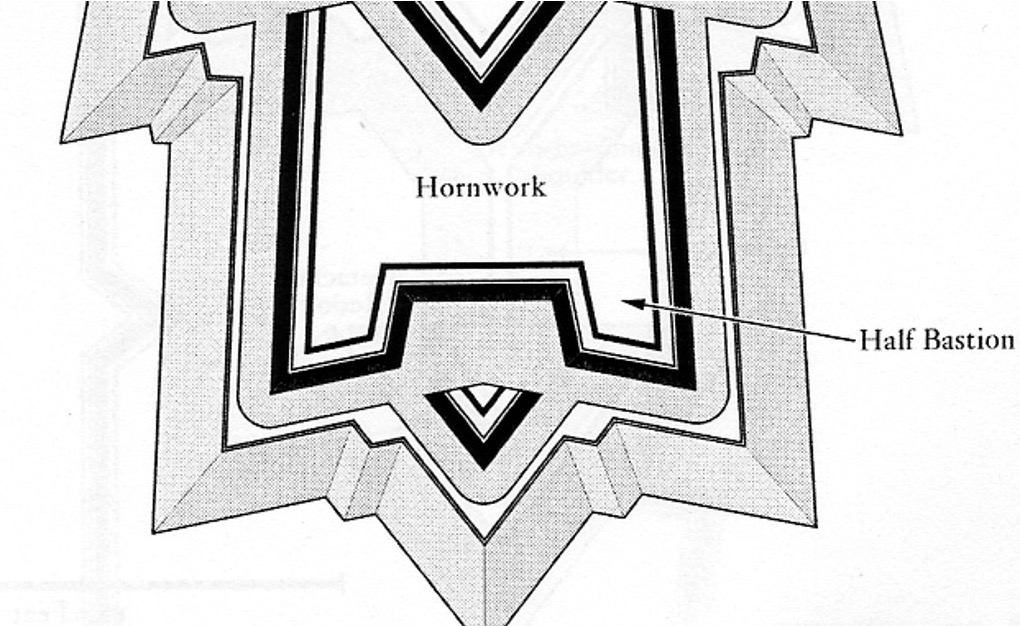

In the vocabulary of military architecture, a “horn work” is a sort of broad fortress with a central gateway situated on the outskirts of a fortified town, the main purpose of which is to defend the approach or path to the settlement from the advance of potential enemies. The name itself is derived from a characteristic feature common to all horn works: a pair of half-bastions projecting outward to the left and to the right of a central wall or “curtain” that includes a gateway straddling the pathway into town. These half-bastions, which provide defenders additional angles to fire at approaching enemies, resemble horns projecting from the sides of an animal’s head. Similarly, if such a fortification included a third bastion in the center of the curtain wall, it would be called a “crown work” because of its resemblance to a monarch’s crown.[1]

In the vocabulary of military architecture, a “horn work” is a sort of broad fortress with a central gateway situated on the outskirts of a fortified town, the main purpose of which is to defend the approach or path to the settlement from the advance of potential enemies. The name itself is derived from a characteristic feature common to all horn works: a pair of half-bastions projecting outward to the left and to the right of a central wall or “curtain” that includes a gateway straddling the pathway into town. These half-bastions, which provide defenders additional angles to fire at approaching enemies, resemble horns projecting from the sides of an animal’s head. Similarly, if such a fortification included a third bastion in the center of the curtain wall, it would be called a “crown work” because of its resemblance to a monarch’s crown.[1]

A horn work, in the general sense of the term, is a species of military architecture described in scores of fortification textbooks published in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe. It was just one of a number of different types of defensive works that all military engineers of that era were expected to understand. Every species of fortification—like a bastion, a ravelin, or a redout—served a specific function and was suited to a specific situation, and their respective designs were all dictated by a well-established set of geometric rules. In the international landscape of military fortifications, Charleston’s eighteenth-century horn work was not a unique entity. In the long history of South Carolina, however, our Horn Work (for which I’m using initial capitals) was a unique and exceptional structure that merits our attention and appreciation. If nothing else, this structure might have been the only horn work ever built of tabby.

What is Tabby?

Tabby is a type of concrete that was once commonly used in the Lowcountry of early South Carolina and elsewhere. Occasionally spelled “tappy” in historic sources, this building material transformed locally-abundant natural resources into a relatively simple and cheap alternative to traditional masonry construction. Laborers transported sand, ash, broken oyster shells, and powdered lime (derived from burnt oyster shells) to a job site or retrieved them from sources on the spot. After combining those ingredients with water to form a viscous slurry, laborers poured the tabby mixture into a temporary form made of parallel wooden planks connected by wooden dowels. The dimensions of the form varied but were generally in the range of one to three feet in breadth and one to two feet in depth; the length of the form was determined by a number of variables. Once the slurry had dried sufficiently to form a solid mass, the form could be dismantled by sliding the wooden dowels out of the recently-poured slab and removing the wooden planks from each side. By reassembling the same wooden form on top of the cured tabby and repeating the process a number of times, the successive layers of tabby eventually formed a solid vertical wall of any desired height. Surviving examples of tabby work in the South Carolina Lowcountry often include dowel holes and horizontal lines that illustrate such a repeated sequence of actions.

Tabby was often used in early South Carolina to pour slab floors, to construct foundations for wooden buildings, and occasionally to form the walls of entire structures. Its use seems to have been more common around Beaufort and the Port Royal area, however, as fewer examples of historic tabby construction have been found in the vicinity of Charleston.[2] Whatever the reason behind that fact, we know that tabby was considered a novel construction material for fortifications in the Charleston area in 1757. In February of that year, the South Carolina Commissioners of Fortifications, an administrative board created in 1736 and appointed by the governor, ordered “a trial of tabby work” for some repairs to Fort Johnson on James Island. Thomas Gordon, a local bricklayer and tabby expert, then poured a pair of parallel tabby walls to form the inner and outer faces of a broad parapet that was later filled with earth to create a solid mass. The experiment apparently convinced the commissioners that tabby was more permanent than earthen fortifications and cheaper than brickwork, and they hired Gordon to do further work at Fort Johnson and elsewhere.[3]

Tabby was often used in early South Carolina to pour slab floors, to construct foundations for wooden buildings, and occasionally to form the walls of entire structures. Its use seems to have been more common around Beaufort and the Port Royal area, however, as fewer examples of historic tabby construction have been found in the vicinity of Charleston.[2] Whatever the reason behind that fact, we know that tabby was considered a novel construction material for fortifications in the Charleston area in 1757. In February of that year, the South Carolina Commissioners of Fortifications, an administrative board created in 1736 and appointed by the governor, ordered “a trial of tabby work” for some repairs to Fort Johnson on James Island. Thomas Gordon, a local bricklayer and tabby expert, then poured a pair of parallel tabby walls to form the inner and outer faces of a broad parapet that was later filled with earth to create a solid mass. The experiment apparently convinced the commissioners that tabby was more permanent than earthen fortifications and cheaper than brickwork, and they hired Gordon to do further work at Fort Johnson and elsewhere.[3]

Is the Horn Work part of Charleston’s “Walled City”?

The phrase “Walled City” has been heard in Charleston a lot in recent years, especially since the creation of the Mayor’s Walled City Task Force in 2005. As a member of that volunteer collective, it’s been my honor to participate in a broad effort to foster a better public understanding of the fortifications that dominated the landscape of eighteenth-century Charleston. Between 1680 and 1780, South Carolina’s provincial government funded the construction of an expanding and evolving system of fortifications on the peninsula between the Ashely and Cooper Rivers. Their purpose was to defend the colonial capital, Charleston, and the fortifications grew in step with the size of the town’s population and its built environment. Nearly all of those accumulated works, built of earth, wood, brick, and tabby, were erased from the landscape during the late 1780s (see Episode 74), but remnants survive underground throughout the city.

Many people use the phrase “Walled City” to refer to one specific period of Charleston’s fortified history that was defined by a system of walls that surrounded sixty-two acres of high land between 1703 and about 1730, as illustrated in the so-called Crisp Map of 1711. In this specific meaning of the phrase, the Horn Work, part of which survives in Marion Square, lies outside the “walled city” both geographically and chronologically. Alternatively, we can also use the phrase “walled city” to describe the evolving network of urban fortifications that were built in a century-long series of construction campaigns that were, in turn, motivated by the succession of wars between Britain and her various enemies. In this broader sense of the phrase, the Horn Work is definitely one of the most significant features of the “walled city” of early Charleston. I firmly believe that fostering a better understanding and appreciation of this large tabby fortress will help to improve public awareness of the city’s colonial fortifications in general, and advance the mission of the Mayor’s Walled City Task Force.

When and Why was the Horn Work built?

The Horn Work was built in the latter part of a local campaign of fortification construction that commenced in 1755 and ended in 1759. Initially motivated by fear of a French attack during what Americans call the French and Indian War and the British call the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), that fortification campaign ended when South Carolina authorities realized that most of the French Army and Navy was too busy defending Canada to consider launching an invasion of the southern colonies.

The Horn Work was built in the latter part of a local campaign of fortification construction that commenced in 1755 and ended in 1759. Initially motivated by fear of a French attack during what Americans call the French and Indian War and the British call the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), that fortification campaign ended when South Carolina authorities realized that most of the French Army and Navy was too busy defending Canada to consider launching an invasion of the southern colonies.

Charleston’s Horn Work, like similar works in contemporary Europe, was a fortified gateway intended to defend the northern approach to the town and control the flow of traffic along the “Broad Path” (now King Street), which was then the only road leading in and out of Charleston. It was the third such structure in the history of colonial Charleston and replaced earlier fortified gates that once stood at the intersection of Broad and Meeting Streets (ca. 1704–ca. 1730) and at the intersection of King and Market Streets (1745–1750). Unlike those earlier structures, which were connected to a system of adjacent walls and moats and situated immediately adjacent to the town, the Horn Work was a free-standing, detached work, the gateway of which was nearly seven hundred yards or approximately 600 meters north of the town boundary at the time of its construction. That distance was intended to provide space for both future civilian expansion and for later defensive works that would eventually flank the lonely Horn Work.[4]

The Horn Work was designed by a young Swiss engineer working for the British Army, Lieutenant Emanuel Hess, who died at Lancaster, Pennsylvania in February 1759. Lieutenant Hess (spelled “Hesse” in South Carolina records, probably reflecting the pronunciation) came to Charleston in June 1757 with Lieutenant Colonel Henry Bouquet and part of the first battalion of His Majesty’s 60th Regiment of Foot (the “Royal Americans"). During their nine months residency here, Hess inspected various fortifications in the area, conversed with local authorities, and made recommendations for improvements and additions. More specifically, he designed an expansion of Fort Johnson on James Island, an entirely new fort near Beaufort, called Fort Lyttelton, and the Horn Work on the north side of urban Charleston.[5] All of these structures were built using tabby, a material that might have been unfamiliar to Lieutenant Hess before his arrival in South Carolina.

Construction of the Horn Work commenced in what is now Marion Square in mid-November 1757 by digging trenches for the foundations of the tabby structure. During the initial months of construction, most of the labor was drawn from members of two British regiments: Lt. Col. Bouquet’s 60th Regiment of Foot and Colonel Archibald Montgomerie’s 62nd Regiment of Foot (later renamed the 77th Regiment of Highlanders). Following the departure of those troops in the spring of 1758, construction continued for another year using the labor of local enslaved men of African descent.

Construction of the tabby Horn Work stopped in the spring of 1759 for a variety of political and economic reasons, and the southernmost third part of the Horn Work was left unfinished. Over the next two decades, the massive oyster-shell walls funneled all traffic along King Street through the unfinished gateway, which locals frequently called Charleston’s “new gate” and occasionally described it as the “white gate.”

Did the Horn Work have a moat?

Just like the scores of other horn works built in Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Charleston’s Horn Work included a large moat or ditch on the north side facing away from the town. The entire area in front of the curtain wall and wrapping around the outer sides of the half-bastions was excavated to a depth of approximately six feet, and the earth removed from the ditch was used to create elevated platforms for the defenders inside the work. If there was a water source nearby, the ditch could be flooded and drained using wooden trunks. It’s difficult to imagine today, but tidal creeks from both the Ashley and Cooper Rivers once flowed inland along what is now Calhoun Street, very nearly to Marion Square, and it’s possible that the moat surrounding the Horn Work was occasionally full of water. The water table is also approximately five feet below the surface of Marion Square, so a broad ditch excavated to a depth of six feet would be naturally wet.[6]

Just like the scores of other horn works built in Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Charleston’s Horn Work included a large moat or ditch on the north side facing away from the town. The entire area in front of the curtain wall and wrapping around the outer sides of the half-bastions was excavated to a depth of approximately six feet, and the earth removed from the ditch was used to create elevated platforms for the defenders inside the work. If there was a water source nearby, the ditch could be flooded and drained using wooden trunks. It’s difficult to imagine today, but tidal creeks from both the Ashley and Cooper Rivers once flowed inland along what is now Calhoun Street, very nearly to Marion Square, and it’s possible that the moat surrounding the Horn Work was occasionally full of water. The water table is also approximately five feet below the surface of Marion Square, so a broad ditch excavated to a depth of six feet would be naturally wet.[6]

To provide access to the gateway in the center of the curtain line, horn works generally included an elevated bridge through the moat or ditch and leading to a drawbridge in front of the gate. Because Charleston’s Horn Work was left unfinished in 1759, however, construction of some of these features might have postponed for two decades. Eyewitnesses in the years before the American Revolution state that there was no gate or doors mounted in the gateway leading into the structure.[7] If there was no gate or doors, then there probably was no bridge. It’s also possible that the moat or ditch was not excavated until the time of the American Revolution.

The penetration of British soldiers into South Carolina in early 1779 motivated local authorities to prepare the Horn Work for combat duty. By the early months of 1780, a moat, bridge, and an upward-swinging draw gate were definitely present. One German soldier who arrived on the scene that spring, Captain Johann Ewald, described the moat in front of the horn work in his diary. Initially viewing the Horn Work from a distance, Ewald heard others remark that it was surrounded by “a broad dry ditch.” When he finally approached the work and passed through its gates, he stated that it had “a rather muddy ditch, over which leads a stone bridge.”[8] Twenty years later, Governor John Drayton (1766–1822), who was a young teenager during the American Revolution, recalled that the “wet ditch” in front of the Horn Work was “so wide and deep, as scarcely ever to be dry.”[9]

How big was the Horn Work?

Surviving physical and documentary evidence of the tabby Horn Work has been very useful in recent attempts to estimate its size and scope. In addition, a brief archaeological excavation in 1998 and recent remote sensing (using ground-penetrating radar) have provided valuable clues for improving our understanding of the work’s design and dimensions.[10] Based on these sources, we can estimate that the tabby curtain wall of the Horn Work measured approximately three hundred and thirty feet across and included a central gateway that straddled King Street. The distance between the outermost points of the two half bastions measured approximately seven hundred feet. Its ditch or moat extended approximately thirty-three feet beyond the tabby walls of the half-bastions, further enlarging the footprint of the overall fortification.

When completed and enclosed in the spring of 1780, the Horn Work stretched from modern Tobacco Street (next to the old Citadel building) on the north well into modern Calhoun Street on the south. Its eastern half covered more than half of what is now Marion Square, while the western half of the Horn Work stood where there are now a number of buildings on the west side of King Street, including a parking garage, St. Matthew’s Lutheran Church, and a number of buildings belonging to the College of Charleston. The site of the Francis Marion Hotel would have been within the Horn Work, but near the southern wall, which was made of earth and wood. Including the tabby work on its north side, the earthworks on the its south side, and its surrounding moat or ditch, this Horn Work covered approximately eight to ten acres of real estate along the northern edge of colonial-era Charleston. An American-sized football field would have easily fit within its walls.

Extant historical sources provide far less information about the height of the walls of the Horn Work. Several illustrations from the era of the American Revolution provide plan-views of the site, but no contemporary profiles or elevations have yet been found. One French observer in 1780 noted that the cannon mounted within the Horn Work “had thirty feet elevation” over their British counterparts—a height comparable to the surviving Castillo de San Marco in St. Augustine, Florida.[11] While it’s possible that this French eye-witness reported an accurate measurement, other interpretations are possible. He might have been measuring from the bottom of the adjacent ditch, as was common in military architecture of that era, or he might have simply exaggerated the height of the American cannon.

Considering that the surviving tabby remnant in Marion Square is approximately two feet thick, it’s difficult to imagine such a slender fortification wall extending thirty feet above the ground without significant buttressing to keep it stable. It seems logical and likely, therefore, that the front wall of the Horn Work—whatever its height—was backed by a significant volume of earth raised high above the surrounding terrain to create an elevated platform for cannon and soldiers. Whether or not the original design of the Horn Work included a second, “inner” wall, parallel to the visible remnants, is a matter for future investigation. In short, a number of construction theories are currently being considered in the hope of reaching a reasonable estimate of its height in the future.

Considering that the surviving tabby remnant in Marion Square is approximately two feet thick, it’s difficult to imagine such a slender fortification wall extending thirty feet above the ground without significant buttressing to keep it stable. It seems logical and likely, therefore, that the front wall of the Horn Work—whatever its height—was backed by a significant volume of earth raised high above the surrounding terrain to create an elevated platform for cannon and soldiers. Whether or not the original design of the Horn Work included a second, “inner” wall, parallel to the visible remnants, is a matter for future investigation. In short, a number of construction theories are currently being considered in the hope of reaching a reasonable estimate of its height in the future.

Was the Horn Work ever used in combat?

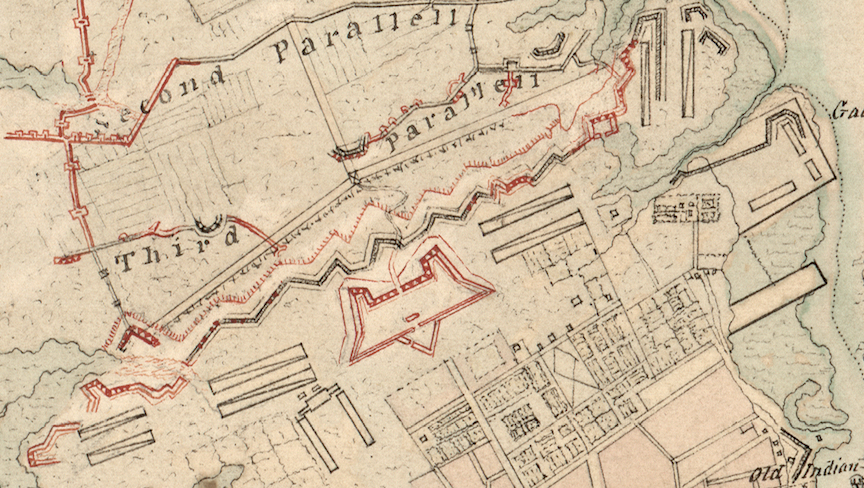

During the American defense of Charleston against British forces in 1779 and 1780, the Horn Work formed the command post and the center of a zig-zag line of multi-layered defensive works that stretched across the peninsula from the Ashley to the Cooper River. Under the guidance of French engineers during that period, laborers enclosed the unfinished rear (south) portion of the Horn Work with walls hastily constructed of earth and wood. General Benjamin Lincoln, the senior American commander during the protracted British siege of 1780, informed his troops that the enclosed Horn Work was to serve as “a place of retreat for the whole army” if enemy forces were to storm the defensive lines in a frontal attack.[12] A few weeks later, British Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton led his infamous dragoons through the Horn Work and described it as “a kind of citadel.”

During the siege of 1780, the Horn Work was occupied and defended by a number of men representing various military units. The command staff were apparently sheltered with an unknown number of tents erected within its walls, while several thousand American soldiers camped around the periphery of its moat. Behind the parapet of the front or northern wall stood eighteen large cannon that fired through deep embrasures at the approaching British army. The management of these elevated guns was entrusted to two organizations that apparently rotated duty in alternating shifts: the 4th South Carolina Continental Regiment of Artillery, commanded by Colonel Barnard Beekman, and an elite militia unit called the Charleston Battalion of Artillery, under Major Thomas Grimball. Two of Grimball’s subordinates, Captain Thomas Heyward Jr. and Captain Edward Rutledge, are remembered today as signers of the Declaration of Independence, but the names of most of the defenders, including dozens of enslaved men risking their lives for liberty, are now lost.

On the afternoon of May 11th, 1780, after several weeks of near-constant shelling, the Americans defending Charleston “hoisted a large white flag on the hornwork . . . offering the capitulation of the city.” On May 12th, a long stream of American soldiers marched out of the gate of the Horn Work, led by the Charleston Battalion of Artillery, and piled their muskets before the enemy army. British generals Henry Clinton and Alexander Leslie, both on horseback, rode forward ahead of a column of red coats. General Benjamin Lincoln, also on horseback, and General William Moultrie on foot, received their adversaries under the gate of the Horn Work. Here, in what is now the middle of King Street, the American commanders exchanged salutations with their adversaries and officially surrendered Charleston to British control. Moments later, a company of British Grenadiers raised their national flag above the ramparts of the Horn Work, signaling to the town that the siege was over.[13]

When and Why was the Horn Work demolished?

There is some documentary evidence that the British forces in control of Charleston between May 1780 and December 1782 repaired and modified some of the local fortifications, including the Horn Work, in case the Americans attempted to attack the occupied town. Such work was probably conducted under the supervision of British engineer Major James Moncrief in 1781, but further research on this topic remains to be done.

On the heels of evacuating British Forces on December 14th, 1782, American soldiers marched into the Horn Work that day and reclaimed Charleston from enemy hands. After the settlement of a permanent peace in 1783, the civil government of South Carolina transferred custody of the Horn Work and its surrounding acreage to the newly-established City Council of Charleston. At some point in the year 1784, the municipal government paid workmen “for leveling the Horn-work,” but the extent of that initial demolition work is unclear.[14] It seems likely that the earthen components used in its construction were pulled down at that time and used to refill and “level” the moat or ditch. Most of the tabby work was knocked-down to ground level in the final years of the eighteenth century, but the chronology of that work was poorly recorded.

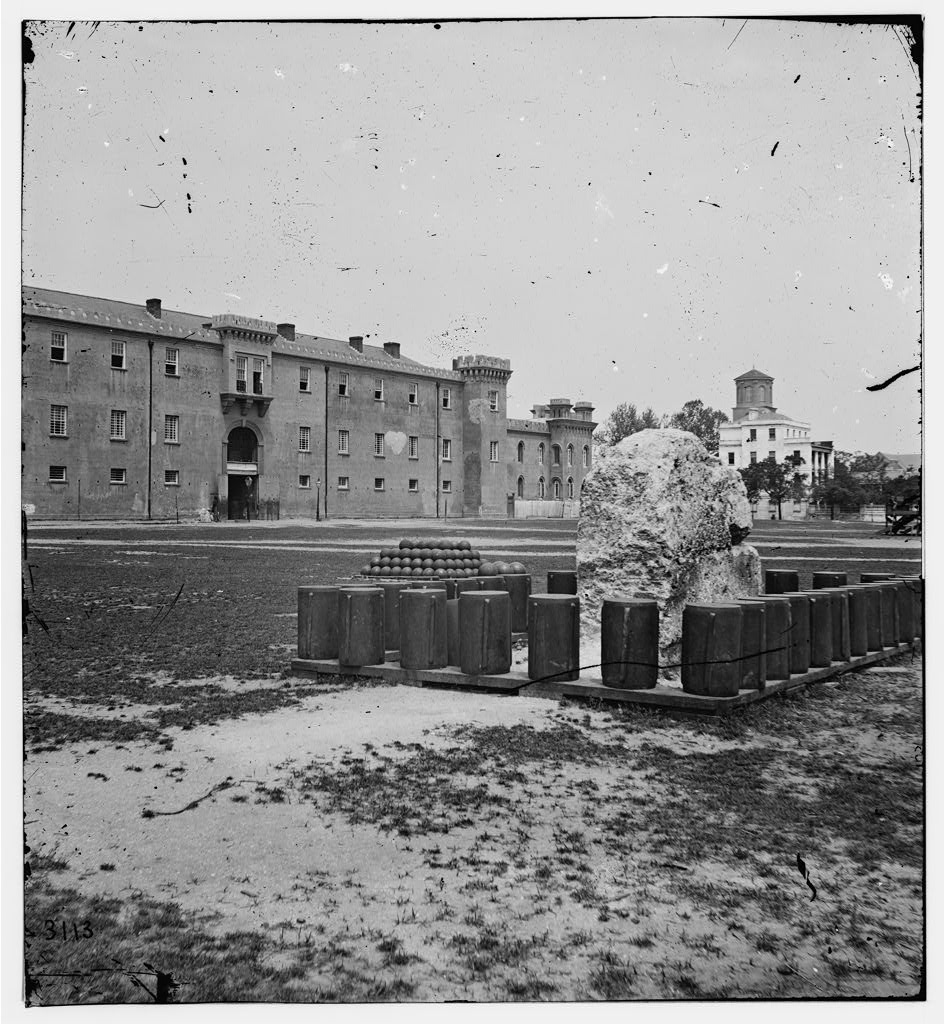

At least one small standing remnant of the Horn Work survived to be photographed by a Union soldier in the spring of 1865. That gray slab, which is just a few feet shy of the eastern end of fort’s curtain line, was something of a local curiosity when the City of Charleston adopted the name Marion Square in 1882 and declared the site to be a part-time public park (see Episode No. 20). Although Francis Marion had no connection to the history of the Horn Work during the American Revolution, the city leaders at least understood the significance of the site’s military history. City funds were used in 1883 to purchase a modest iron fence and commission a small metallic plaque that reads “Remnant, of Horn Work. May 1780. Siege of Charleston.”

At least one small standing remnant of the Horn Work survived to be photographed by a Union soldier in the spring of 1865. That gray slab, which is just a few feet shy of the eastern end of fort’s curtain line, was something of a local curiosity when the City of Charleston adopted the name Marion Square in 1882 and declared the site to be a part-time public park (see Episode No. 20). Although Francis Marion had no connection to the history of the Horn Work during the American Revolution, the city leaders at least understood the significance of the site’s military history. City funds were used in 1883 to purchase a modest iron fence and commission a small metallic plaque that reads “Remnant, of Horn Work. May 1780. Siege of Charleston.”

How can I learn more about this topic?

It’s my hope that this brief overview of the Horn Work will facilitate conversations about the future of this important part of our community’s history. This long-forgotten fortification was a once a major landmark on the streetscape of urban Charleston, but its significance extends far beyond local boundaries. This tabby fortress formed the defensive citadel of the longest siege of the American Revolution. It served as the gateway to both Charleston’s darkest day on May 12th, 1780 and its brightest victory on December 14th, 1782. Its heroic walls were discarded in later years, but it’s not too late to preserve the surviving remnants and celebrate their dramatic story.

At this moment, there are a number of individuals and organizations working to gather information and stimulate further study of Charleston’s Horn Work. We already have a wealth of documentary resources, but there are still many unanswered question. For example, the Horn Work is depicted in some detail in a number of maps of Charleston’s fortifications produced during the American Revolution, but all of these illustrations include variations and discrepancies that frustrate our ability to determine which is more accurate or reliable. In order to better promote and curate the legacy of the Horn Work, including visible portions above ground and obscured foundations below the surface, we need to have a more complete understanding of the location, dimensions, and condition of all of the surviving materials in Marion Square.

In lieu of costly and disruptive archaeological excavations in Marion Square, which the Field Officers of the Fourth Brigade of the South Carolina Militia have owned since 1833, Jon Marcoux of Clemson University’s graduate historic preservation program has been conducting ground-penetrating radar in the park in recent weeks with student help. That unobtrusive work is generating valuable data that will be studied and shared as the investigation continues.

For the present, I highly recommend an excellent book about the 1780 British siege published in 2003 by Carl Borick of the Charleston Museum, appropriately titled A Gallant Defense. You can also view a 2014 video of me talking about the Horn Work before an audience at the Charleston County Public Library. As this project gathers steam and gains traction in the coming months, I also recommend keeping an eye on the website of the South Carolina Battlefield Preservation Trust, which is partnering with a number of local, state, and national agencies to share the story of Charleston’s Horn Work. In conjunction with those folks, I plan to create series of essays in the coming weeks treating the construction, use, and demolition of the Horn Work in greater detail. Even if you’re not a fan of military history, I promise that the story of the rise and fall of Charleston’s tabby fortress contains plenty of color and drama to hold your attention.

[1] For a good introduction to the vocabulary of fortification, see Christopher Duffy, Fire and Stone: The Science of Fortress Warfare, 1660–1860 (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1975)

[2] For more information about the local use of tabby, see Colin Brooker, The Shell Builders: Tabby Architecture of Beaufort, South Carolina, and the Sea Islands (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2020).

[3] South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Journal of the Commissioners of Fortifications, 17 and 24 February 1757, 16 June 1757.

[4] For more information about the earlier gateways of colonial-era Charleston, see the timeline on the website of the Mayor’s Walled City Task Force.

[5] During the latter half of 1757 and early 1758, the surviving journals of the South Carolina Commissioners of Fortifications and the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly contain many references to Lieutenant Hess.

[6] Natalie P. Adams, “Now a Few Words about the Works . . . Called the Old Royal Work”: Phase I Archaeological Investigations at Marion Square, Charleston, South Carolina. New South Technical Report #556 (Stone Mountain, Ga.: New South Associates, 1998), 26–27.

[7] See, for example, the account of an anonymous 1774 visitor in H. Roy Merrens, ed., The Colonial South Carolina Scene, 283.

[8] Bernhard A. Uhlendorf, ed. and trans., The Siege of Charleston. With an Account of the Province of South Carolina: Diaries and Letters of Hessian Officers from the von Jungkenn Papers in the William L. Clements Library (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1938), 37–39, 91.

[9] John Drayton, A View of South-Carolina, As Respects Her Natural and Civil Concerns (Charleston, S.C.: W. P. Young, 1802), 206.

[10] Natalie P. Adams, “Now a Few Words about the Works . . . Called the Old Royal Work”: Phase I Archaeological Investigations at Marion Square, Charleston, South Carolina. New South Technical Report #556 (Stone Mountain, Ga.: New South Associates, 1998).

[11] Richard K. Murdoch, trans., “A French Account of the Siege of Charleston, 1780,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 67 (July 1966): 150.

[12] Banastre Tarleton, A History of the campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America (London: T. Cadell, 1787; Reprint, Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Company, 1967), 13; Carl Borick, A Gallant Defense, 200.

[13] Uhlendorf, ed. and trans., The Siege of Charleston, 289–93; Murdoch, “A French Account,” 151.

[14] See the report of city expenses, 1783–85, in Charleston Evening Gazette, 3 September 1785.

PREVIOUS: Hucksters’ Paradise: Mobile Food in Urban Charleston, Part 2

NEXT: The Rise of Charleston's Horn Work, Part 1

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments