Hog Island to Patriots Point: A Brief History

Processing Request

Processing Request

Patriots Point is a well-known landmark on the east bank of the Cooper River in the Town of Mount Pleasant, but its modern name obscures a much deeper history. Known as Hog Island before 1973, the site has been radically transformed by nature and humans over the past three centuries. Its evolution from a tiny but habitable island, to an expansive vacant marsh, to a thriving community atop a mountain of dredge spoil, illustrates the shifting dynamics of tidal forces and human engineering that have reshaped the local ecology.

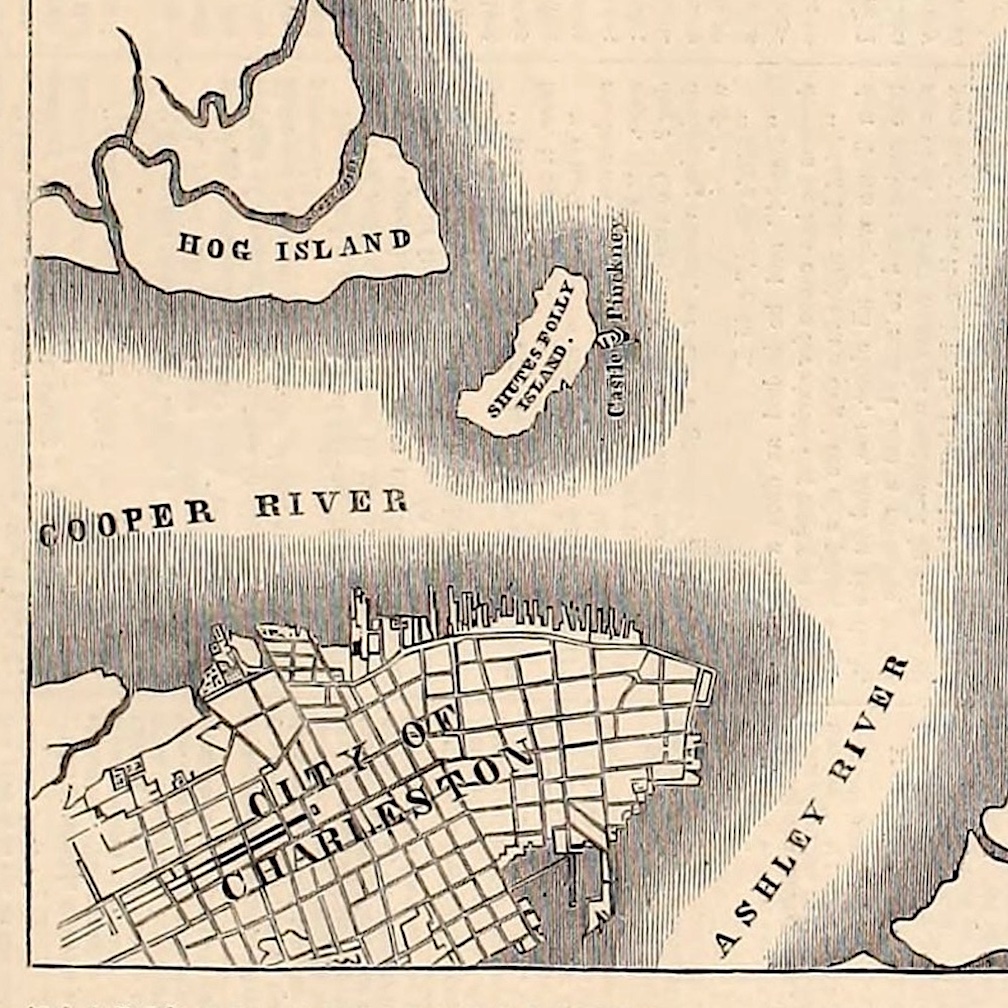

There are numerous sites called Hog Island along the Atlantic Coast of the United States and elsewhere, but the subject of the present conversation stands within Charleston Harbor. Our Hog Island is a rather large feature projecting boldly from the mainland of Mount Pleasant into the Cooper River. Although it is physical distinct from the sandy whisp of a mudflat known as Shute’s Folly, situated near the center of the harbor, the two sites are historically interrelated. I’ll defer the story of Shute’s Folly to a later date, but I’ll draw attention to a curious graphic phenomenon at the heart of the present conversation. Maps of Charleston Harbor made over the course of the eighteenth century depict Shute’s Folly as an expansive body of marshland separated from a much smaller version of Hog Island by a relatively inconsequential creek. Modern readers comparing such maps with satellite images of the same landscape might wonder if the old maps are inaccurate, or if the topography in question has really changed that drastically. To answer this question, we have to travel back in time using documents available in local archives.

The extant paper trail of Hog Island history begins in the autumn of 1694, when the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, through their deputies in Charleston, granted a tract of seventeen acres to a wealthy settler named Edmund Bellinger. A plat of the property made in May 1694 described it as “a plantation containing seventeen acres of land . . . known by the name of Hogg Island,” lying on the north side of Hog Island Creek (now Hog Island Channel), south of a small inlet then known as Sullivan’s Creek (now Hog Island Creek), and bounded to the east and west by marshland.[1] From this description, we learn that the name “Hog Island” was already in use by 1694. It’s likely that someone had placed hogs on the island during the early days of European settlement to let them roam freely and forage for themselves. The most obvious candidate for performing this work is Florence O’Sullivan, who owned the adjacent mainland on the east side of Shem Creek, now called Haddrell’s Point (see Episode No. 252).

Edmund Bellinger acquired thousands of acres across the Lowcountry around the turn of the eighteenth century, and apparently did nothing remarkable with Hog Island before his death in 1709. Immediately after his demise, Bellinger’s widow, Elizabeth, sold the island to Alexander Parris, who later became treasurer of South Carolina.[2] Three years later, in early 1712, Parris obtained a grant from the colony’s provincial government for two hundred acres of marshland adjacent to and west of the seventeen acres known properly as Hog Island.[3] The large tract of vacant, tidal marshland that Parris acquired in 1712 now encompasses the bulk of the attractions of modern Patriots Point.

In January 1725, Alexander Parris conveyed Hog Island to a pair of men who pledged to hold the property in trust for the benefit of his wife, Mary. This arrangement was a means of compensating Mary for waiving her dower rights in another island they jointly owned in Port Royal Harbor (i.e., Parris Island). According to the terms of the 1725 trust established for the administration of Hog Island, Alexander was obliged to build “upon some convenient part of the premisses[,] one good substantial messuage or tenement of timber with brick chimneys at each end[,] the same to be thirty two feet long and sixteen feet wide[,] and a shed [i.e., porch] to be added of the whole length of the house[,] the story to be ten feet high and the two rooms above to be lathed and plaistered[,] and to have three dormant [sic] windows, the whole house to be boarded without [i.e., outside] with inch [thick] boards and lathed and plastered within and sieled at top, the windows to be glazed.”[4]

The first and only residential structure on Hog Island was duly built circa 1725–27 for Mary Parris, but she did not reside there. Rather, it was designed as rental property that would generate a steady stream of income for Mary’s exclusive use. Just a few years later, however, Mary and her husband and trustee sold the property in the spring of 1731 to John Gascoigne, captain of His Majesty’s Ship Aldborough (frequently misspelled Alborough).[5] This twenty-gun frigate was stationed in Charleston between 1728 and 1734, but assigned to survey the coastlines of South Carolina, Florida, the Bahamas, and the Windward Passage between the islands of Cuba and Hispaniola.[6] Captain Gascoigne, like other Royal Navy officers serving on the Carolina Station, spent the majority of his time ashore in Charleston, and might have rented the Hog Island house from Mary Parris soon after his arrival in 1728, or perhaps after the arrival of his wife, Mary Anne, shortly thereafter.[7] He acquired other investment property in South Carolina in the early 1730s, but his tenure in the colony was a temporary assignment. Gascoigne advertised to sell Hog Island in the spring of 1734, and his description of the property provides a valuable snapshot of the landscape at that moment:

“To be let or sold, An island opposite to Charles Town commonly call’d Hog-Island, being a very commodious situation for a carining wharfe and for a ferry. The creeks round it affording perfect security for boats and periaguas in the most stormy weather: as the main-creeks doth for ships of the greatest draught: and they abound with such a continual plenty of fish that the town may be constantly serv’d from thence. On the Island is a new dwelling house &c. built on an high bluff, which commands an entire prospect of the harbour, from the barr to the town. A delightful wilderness with shady walks and arbours, cool in the hottest seasons. A piece of garden-ground, where all the best kinds of fruits and kitchen greens are produced, and planted with orange, apple-, peach-, nectarine-, and plumb-trees, capable of being made a very good vineyard and of other great improvements.”[8]

Gascoigne sold the island to James Searles, “victualer and periagua man” of Christ Church Parish, in late March 1734. Searles financed the purchase by mortgaging the property to Gascoigne and agreeing to make a series of four annual payments. Until the mortgage was satisfied, Searles agreed that he “shall not cut down or destroy or suffer to be cut down or distroy’d [sic] any of the fruit trees or other trees woods or underwoods now standing and growing” on the island, and agreed to maintain “the dwelling house out houses and all other the edifices on the said land now standing and in good repair.”[9]

Captain Gascoigne received orders from the British Admiralty to sail the Aldborough back to England in April 1734, at which time he assigned power of attorney to his brother-in-law, Thomas Gadsden.[10] Mr. Gadsden, father of the famous Christopher Gadsden, was empowered to receive the mortgage payments due for Hog Island, but James Searles failed to complete the purchase. John Gascoigne retired in 1747 with the rank of Rear-Admiral of the Royal Navy and still held title to Hog Island at the time of his death in 1753. According to the terms of his will, Admiral Gascoigne’s eldest son, William, in London, inherited all of his property in South Carolina.[11] In the autumn of 1770, William Gascoigne empowered his cousin, Christopher Gadsden in Charleston, to sell Hog Island. Gadsden then made a bargain with another cousin, Thomas Hasell, who purchased the seventeen-acre island in October 1771, and then immediately sold the property back to Gadsden.[12]

Christopher Gadsden retained ownership of Hog Island for the remainder of his long life, during which time the natural forces of wind and waves eroded most of the habitable land. Surviving records from the second half of the eighteenth century contain no further mention of the house and orchard standing on the property in 1734. Conversely, documents from that same era demonstrate that the inlet described as Hog Island Creek in 1694 had widened into a navigable channel, which American mariners attempted to block in November 1775 by scuttling several vessels to prevent the ingress of British warships at the beginning of the American Revolution.[13] The widening of the channel no doubt contributed to the leveling of Hog Island, and this hydrological change became the dominant theme in the narrative of the island’s history.

After the death of General Christopher Gadsden in 1805, his executors found the original plat of Hog Island, made in May 1694, among his papers. That seventeenth-century document is now lost, but a faithful copy made in 1806 survives.[14] Much of Gadsden’s extensive estate was advertised to be sold at auction in August 1807, including “the remainder of Hog-Island, in the harbor opposite the city, supposed to be about five acres.”[15] The highest bidder for the diminished island was Christopher Edwards Gadsden, grandson of the general, a young clergyman later known as Bishop Gadsden.[16]

Through some means yet unknown, Reverend Gadsden conveyed the entirety of Hog Island—both the small quantity of high ground and the large swath of marsh—to Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and his brother, Thomas Pinckney, in 1808. That spring, the Pinckney brothers obtained a grant from the State of South Carolina for a further seventy-five acres located between the aforementioned historical tracts.[17] Plats of this landscape made in 1821 demonstrate that the Pinckneys still claimed nearly three hundred acres of vacant marshland collectively known as Hog Island. Those same plats depict the original seventeen-acre island as nothing more than a field of small scattered hummocks near the mouth of Shem Creek.[18]

Generals Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Thomas Pinckney died in 1825 and 1828, respectively, and devised a significant amount of real estate to their numerous heirs. Neither general mentioned Hog Island in his will, however, and the paper trail of the island’s ownership evaporated after their deaths. Through some means not yet discovered, the entirety of Hog Island became vested in the State of South Carolina at some point around the middle of the nineteenth century. I have not been able to find a paper trail to explain this mystery, but I have a theory to explain the archival silence.

In December 1836, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified a law to regulate the growth of wharves and other waterfront construction projects within Charleston Harbor. Besides limiting the future extension of the commercial wharves, the state law of 1836 also granted to the City of Charleston “all vacant land not legally vested in individuals, in the harbor of Charleston, covered by water.”[19] It seems likely that agents of the City of Charleston applied this clause to the entirety of Hog Island—both the acres of marshland and the remnants of the original island—during the winter of 1836–37.[20]

The purpose of the 1836 wharf law was to address an inflationary trend along the waterfront of urban Charleston: The private wharves projecting from the east side of East Bay Street into the Cooper River interrupted the flow of the tidal waters, which deposited silt at the foot of the wooden structures. The volume of deposited silt increased with the proliferation of wharves in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and the progressive silting induced owners to extend their wharves further and further into the river. The wharf law of 1836 sought to check this trend before the encroaching wharves obliterated the shipping channel, but it also aroused notice of a related problem on the opposite shore of the Cooper River.

In the summer of 1837, a local citizen named James Gadsden Holmes (1797–1882) sent a letter to the mayor of Charleston to share several concerns about the progressive erosion of the west end of Sullivan’s Island and other sites in the harbor. The root cause of this erosion, said Mr. Holmes, was a series of human endeavors that were collectively changing the course of tidal waters flowing through the harbor. The expanding wharves of Charleston and the indiscriminate dumping of silt dredged from the wharves were gradually pushing the channel of the Cooper River to the northeast, away from the Charleston peninsula. The volume of water passing through the traditional ship channel, between the wharves of urban Charleston and Shute’s Folly, was diminishing, while an increasing volume of water passed between Shute’s Folly and Hog Island. The forces of human alteration, said Holmes, “are every way enlarging Hog Island Channel, once inconsiderable, but becoming the main, as it is the direct channel between the rivers and the ocean.”[21]

Holmes expanded his thoughts about the fluid dynamics of Charleston Harbor in a memorial presented to the South Carolina General Assembly in the autumn of 1837. Hoping to restore the original vigor of the shipping channel, he suggested that South Carolina agents in Washington D.C. lobby for Federal funds to close Hog Island Channel by erecting a dam or dyke between Hog Island and the shrinking landmass of Shute’s Folly. Unless such a project was undertaken, said Holmes, Hog Island Channel would eventually become the principal route for shipping traffic through Charleston Harbor, and the wharves of urban Charleston would become useless.[22]

The South Carolina legislature embraced Holmes’ advice in December 1837 and empowered state agents to lobby the United States Congress for the means to obliterate Hog Island Channel.[23] In 1839, a U.S. Engineer in Charleston, Alexander Hamilton Bowman, designed a dam-like structure to close the offending channel, which he noted had doubled in width between 1776 and 1825, while half of Shute’s Folly had disappeared during the same period.[24] South Carolina’s representatives in Congress fought unsuccessfully for more than a decade to secure Federal funds for the construction of Bowman’s barricade.[25] His successor, U.S. Engineer Alexander Dallas Bache, continued to advocate in the 1850s for the closing of Hog Island Channel as a means of preserving and strengthening the traditional ship channel.[26] After the Civil War, local scientists like Francis Simons Holmes of the Charleston Museum renewed the campaign to prevent further damage to the ship traffic that formed the lifeblood of the local economy.[27]

A major turning point in this engineering saga occurred in the spring of 1878, when Congress approved a plan submitted by U.S. Army engineer Quincy Adams Gillmore to construct a pair of massive stone jetties at the entrance to Charleston Harbor. As I described in Episode No. 235, Gillmore’s plan sought to focus the kinetic energy of the daily tides to scour a straighter and deeper channel for ships through the harbor. Work on the jetties commenced in late 1878 and progressed slowly over the ensuing two and a half decades.

While Gillmore’s stone jetties rose slowly from the ocean depths outside the harbor, members of the Charleston Chamber of Commerce lobbied the state government to create a local body responsible for coordinating improvements to Charleston’s inner harbor.[28] The “Harbor Commission for the Bay and Harbor of Charleston,” chartered in December 1880, pressed U.S. Army engineers for help in preserving a sufficient volume of water around the wharves of urban Charleston to facilitate commercial shipping.[29] In July 1881, the Harbor Commission adopted a suggestion from the Army Corps that locals should discontinue the long-standing “custom” of dumping material dredged from the city wharves on the south and west sides of Shute’s Folly. Henceforth, such dredge spoil was to be dumped in the ever-widening channel adjacent to Hog Island.[30]

At the end of 1886, Quincy Gillmore’s annual report on the progress of the jetties confirmed that the width of Hog Island Channel was steadily increasing, as it had over the past twenty years of his observation. He predicted, like James Holmes had fifty years earlier, that the increasing volume of water passing between Hog Island and Shute’s Folly would continue to erode the shoreline of Mount Pleasant and sap the vitality of Charleston’s traditional shipping channel.[31] Resources to address these problems were lacking, however, because the Army Corps of Engineers devoted all their funds and efforts to the construction of the stone jetties at the mouth of the harbor, which were finally completed in 1895.

While engineers tinkered with the dynamics of Charleston Harbor during the final decades of the nineteenth century, a coterie of businessmen sought to facilitate travel across the Cooper River and develop the countryside beyond the village of Mount Pleasant. An opportunity to further such efforts arose after the state government separated Berkeley County from Charleston County in 1882. Within Charleston Harbor, the legislature drew a dividing line between the two counties through the center line of the Cooper River and through Hog Island Channel. By this legal change, the expansive marsh of Hog Island became part of Berkeley County. No one in that new political district held any claim to the vacant property, which was therefore ostensibly vested by eminent domain in the State of South Carolina.[32]

In October 1886, a local developer named Robert Cogdell Gilchrist (1829–1902) convinced the governor of South Carolina to grant him 131 acres of Hog Island—the westernmost half of the marsh, located between the Cooper River and Horse Creek—at the rate of one dollar per acre.[33] Gilchrist dreamed of developing a luxury seaside resort at the eastern end of Sullivan’s Island, to be called Seaview City. To transport customers to this destination, he planned to build a railroad bridge from urban Charleston across the Cooper River to Hog Island, then continuing across Shem Creek, through the village of Mount Pleasant, over the Cove of Sullivan’s Island to the Town of Moultrieville, and eastward to Seaview City. Gilchrist launched this ambitious project in 1874 and persevered into the mid-1890s, despite suffering a series of economic reversals. Along the way, he and his successive companies—the Charleston and Sullivan’s Island Railroad Company and then the Mount Pleasant and Seaview City Railroad Company—gained ownership of the eastern half of Sullivan’s Island, twenty acres in the Village of Mount Pleasant, and a right-of-way for the proposed route. To facilitate the construction of a ferry terminal on Hog Island, to be replaced eventually by a railroad bridge across the marsh island, Gilchrist acquired in 1886 the bulk of the site now known as Patriots Point. He finally abandoned the railroad project in 1897, when a new set of developers unveiled a scheme to construct an electric trolley line along a similar route to Long Island, which they renamed the Isle of Palms in 1898. The rail line to Seaview City was never completed and plans for the grand resort evaporated. Although Robert Gilchrist lost control of most of the investment property he accumulated during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, his heirs retained ownership of the vacant Hog Island marshland until the late 1960s.[34]

Hog Island and its adjacent channel returned to the local spotlight in the spring of 1955, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers made an announcement that was front-page news in Charleston: The main shipping channel through Charleston Harbor was to be moved eastward.[35] Ships entering the harbor since the late seventeenth century had sailed around the west side of Shute’s Folly to reach the wharves of Charleston, but a post-World War II study of tidal dynamics in the harbor suggested a more efficient route. Because the port’s commercial wharves were creeping northward along the Cooper River side of the peninsula, and because Hog Island Channel was growing wider every year, engineers proposed to re-route ship traffic to the east side of Shute’s Folly. In short, they embraced the fluid changes that Charlestonians had sought to eradicate during the previous century.

While the 1955 plan offered a more direct route from the stone jetties at the harbor’s entrance to the wharves on the Neck of the Charleston peninsula, it also required a significant widening and deepening of Hog Island Channel. The Corps of Engineers contracted with private dredging companies to remove many tons of silt, sand, and mud from the channel, and negotiated with locals to secure a site to receive the dredged material. From Mrs. Georgette Gilchrist (1886–1973), the elderly heir of Robert C. Gilchrist, the Corps obtained an easement to dump the spoil on the vacant marsh of Hog Island, adjacent to the new shipping route. Dredging commenced in October 1955 and continued for several years, but the new route around the east side of Shute’s Folly was ready for traffic by the spring of 1956. On April 11th of that year, Hog Island Channel became the official thoroughfare for commercial ships traversing Charleston Harbor.[36]

The widening and deepening of Hog Island Channel in the late 1950s was a boon to the Port of Charleston, but the work frustrated citizens residing on the adjacent mainland. Residents of the Bay View Acres subdivision complained loudly about the swarms of mosquitos that bred in the stagnant water draining from the mountains of dredge spoil, and about the noxious stench emanating from the sun-kissed mud.[37] The Army Corps of Engineers labored every summer to create drainage channels and abate the nuisances, but the complaints continued until the Corps declared Hog Island filled to capacity at the end of 1963.[38]

After more than eight years of dumping, several hundred acres of vacant marsh had been transformed into a bluff standing up to fifteen feet above low water mark. Horse Creek, running along a north-south axis through the center of Hog Island marsh, was completely obliterated by the work.[39] The resulting broad plateau of naked dredge spoil was not an attractive sight, but it held great potential value. Because it was adjacent to the growing Town of Mount Pleasant, stood at the foot of the Cooper River Bridge, and commanded a panoramic view of the harbor, Hog Island quickly became a target for profitable development. In the spring of 1967, Georgette Gilchrist sold 130 acres of Hog Island to a group of business men who planned to develop a private resort.[40] That move aroused the attention of the Charleston County Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Commission (better known as the PRT), which began considering the possibility of transforming the site into a public park. As early as 1970, local agencies and individuals commenced a protracted debate about who really owned Hog Island and who would control its future.[41]

Charleston County PRT unveiled its plan for a proposed 350-acre park and naval museum on Hog Island in June 1971.[42] Soon afterwards, the City of Charleston filed suit against the PRT, claiming that the aforementioned state act of 1836 endowed the city with ownership of the once-vacant marsh island.[43] The Charleston County PRT, despite owning none of the land in question, commissioned a feasibility study for their grand plan. That report, published in August 1972, predicted that the development of a park at Hog Island, complete with an aircraft carrier and other old ships, an aquarium, hotel, and campground, would cost at least $60 million, but it might boost local tourism like Disney World had for the city of Orlando.[44]

The feasibility study also spurred Charleston County administrators to consider rebranding the proposed park. “Hog Island,” after all, was not necessarily the most attractive name to draw crowds of tourists. A public appeal for alternate names produced a number of contenders during the autumn of 1972, but one stood ahead of the rest. Colonel D. D. Nicholson Jr., program chair of the county’s Bicentennial Committee, proposed the name “Patriots Point” (without an apostrophe), which was soon adopted as the proposed park’s unofficial name.[45] Members of the Charleston County PRT made a formal presentation to a group of state legislators in Columbia in January 1973, and both the state Senate and House of Representatives embraced the project. In March of that year, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified an act that officially changed the site’s name from Hog Island to Patriots Point, and simultaneously created the Patriots Point Development Authority to administer the ambitious project.[46]

Legal disputes about the ownership of Hog Island delayed plans for the naval museum, but in March 1974 the Patriots Point Development Authority finally secured the former Gilchrist tract of approximately 130 acres. That acreage represented less than half the size of the park planned by the Development Authority, but it was a sufficient stake in the ground to complete a formal application to the U.S. Navy to take possession of the USS Yorktown.[47] The aircraft carrier known as the ‘Fighting Lady’ sailed from New Jersey the following spring and arrived in Charleston Harbor on the morning of 15 June 1975. Later that afternoon, a squadron of tugboats nudged the Yorktown into the muddy berth adjacent to Hog Island that it still occupies today.

The Town of Mount Pleasant officially annexed Patriots Point in December 1975, and the iconic naval museum opened to the public on 3 January 1976.[48] Meanwhile, the Patriots Point Development Authority continued negotiations to secure the remaining acres of dredge spoil formerly known as Hog Island. Their efforts to complete the original plan for Patriots Point were unsuccessful, but the Authority reached a collaborative agreement with the owners of eastern portion of the site in 1977.[49] The golf course, hotel, and marina now located to the east and south of the naval museum arose from a public-private partnership developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The success of Patriots Point in the late twentieth century fulfilled the dream of creating a diversified attraction that would draw large numbers of tourists from near and far. The site’s mature trees and robust infrastructure create the impression of venerable age, but the modern landscape is a relatively recent layer grafted over a forgotten salt marsh with a very different and poorly-remembered history. The Hog Island claimed by the Pinckney Brothers and by Robert Gilchrist in the nineteenth century is now home to the USS Yorktown, several athletic fields, and a golf course crafted from the remnants of Horse Creek. One mile due east of the aircraft carrier is another historical site far less accessible—the original seventeen-acre site of Hog Island.

Visitors to the recently-created Shem Creek Park in Mount Pleasant can travel back in time by walking to the southern terminus of the raised boardwalk and peering a few degrees to the southwest. There, with the Cooper River and the City of Charleston in the background, you can see the salty remnants of the Hog Island once familiar to Florence O’Sullivan, Edmund and Elizabeth Bellinger, Alexander and Mary Parris, Captain John Gascoigne, and Christopher Gadsden. The house and orchard are long gone, but the hog-like smell of pluff mud lingers in the air.

[1] South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Colonial Land Grants (Copy Series, S213019), volume 38: 151; abstract on page 273. The original plat does not survive, but McCrady Plat No. 2373, held by the Charleston County Register of Deeds (hereafter CCRD), bears the following inscription in the handwriting of surveyor Joseph R. Purcell: “Laid out unto Edmund Bellinger 17 acres [of] land called Hog Island, situated on the northward of Hog Island Creek and to the southward of Sullivants [sic] Creek[,] to the east & west on a marsh[,] butting and bounding as this plat doth represent. Plat certified the 17th May 1694 by Stephen Bull Surv[eyo]r. Copy taken from the original plat in the hands of the executor of Christopher Gadsden E[sq]r de[cease]d the present proprietor in July 1806.” A later copy of this same plat, now McCrady Plat No. 6094, includes the following additional caption: “Copied Septr. 7th 1861 from a copy in Purcell’s hand writing among [surveyor] Charles Parker’s papers.” Note that Henry A. M. Smith, “Hog Island and Shute’s Folly,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 19 (April 1918): 87–94, misread the 1694 description and reversed the names of the creeks in his description of the island.

[2] Elizabeth Bellinger to Alexander Parris, conveyance, 23 March 1708/9, SCDAH, Register of the Province, book G: 214–18.

[3] The plat of Parris’ 200 acres is dated 30 October 1711; see SCDAH, Colonial Plat Books (copy series, S213184), volume 11: 543. I could not find the grant of this marshland, but an 1821 plat of the same 200 acres cited the date of the grant as 30 January 1711/2; see McCrady Plat No. 6027.

[4] Alexander Parris and Mary, his wife, to William Gibbon and Jonah Collins, lease and release in trust, 22–23 January 1724/5 (eleventh regnal year of King George), CCRD D: 184–88; I have retained the original spelling in my transcription.

[5] Alexander Parris and Mary, his wife, of the first part; Jonah Collins, planter of Colleton County, of the second part; to John Gascoigne, “capn. of his majestys shipp of warr named the Alborough now in the harbour before Charlestown,” lease and release, 3–4 March 1730/1 (fourth regnal year of George II), CCRD I: 213–21.

[6] For an overview of Gascoigne’s work, see W. E. May, “The Surveying Commission of Alborough [sic; Aldborough], 1728–1734,” The American Neptune 21 (October 1961): 260–78.

[7] Mary Anne Mighells Gascoigne bore and buried a son name Mighells in October 1732; see A. S. Salley Jr., ed., Register of St. Philip’s Parish Charles Town, South Carolina, 1720–1758 (Charleston, S.C.: Walker, Evans & Cogswell, 1904), 72, 119–20, 240.

[8] South Carolina Gazette, 2–9 February 1733/4 (Saturday), pages 3–4; a more legible copy of the text appears in the issue of 23 February–2 March 1733/4, page 4. I have preserved the original spelling.

[9] James Searles to John Gascoigne, mortgage and bond, 27 March 1734, SCDAH, Records of the Secretary of State, Miscellaneous Records (Main Series, S213003), volume BB (1732–1735), 207–9; James Searles and Christina, his wife, to John Gascoigne, mortgage by lease and release, 26–27 March 1734: CCRD M: 20–32.

[10] John Gascoigne to Thomas Gadsden, power of attorney, 24 April 1734, CCRD M: 59–61.

[11] The will of John Gascoigne, dated 9 January 1743/4, was proved at London on 8 August 1753; National Archives, Kew, PROB 11/803/333.

[12] All of these transactions are recorded in CCRD W3: 347–48; 351–63.

[13] David Ramsay, The History of the Revolution of South Carolina, volume 1 (Trenton, N.J.: 1785), 49; John Drayton, Memoirs of the American Revolution, volume 2 (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1821), 70–74.

[14] McCrady Plat No. 2373; see note 1 above.

[15] City Gazette, 9 July 1807, page 3, “Under Decree in Equity.”

[16] Christopher E. Gadsden to William Hasell Gibbes, Master in Equity, mortgage, 18 August 1807, CCRD U7: 403–4.

[17] A plat of the seventy-five acres in question appears in SCDAH, State Plat Books (Charleston Series, S213190), volume 237, page 114, but I have not yet found the date of the grant for the said acreage.

[18] See McCrady Plat No. 6195 and No. 6027, made by surveyor John Diamond in June and August 1821, respectively.

[19] Act No. 2691, “An Act establishing a Line beyond which the Wharves shall not be extended in the City of Charleston; and for other purposes,” ratified on 21 December 1836, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 151–52.

[20] Section VII of the aforementioned wharf and harbor act of December 1836 obliged the City Surveyor of Charleston “to see that all the provisions of this Act be carried into full effect.” Coincidentally, a note inscribed on McCrady Plat No. 6027 states that Charles Parker, City Surveyor, made a defective plat of Hog Island in 1836. Efforts to locate Parker’s plat of the island have been unsuccessful.

[21] Charleston Courier, 25 July 1837, page 2, “Communications. To the Honorable Robert Y. Hayne, Mayor of Charleston”; Courier, 29 July 1837, page 2, “Charleston Harbor and a Navy Yard.”

[22] Courier, 25 July 1837, page 2, “Communications”; Courier, 29 July 1837, page 2, “Charleston Harbor and a Navy Yard”; Memorial of James G. Holmes, SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly (series S165005), no date, No. 5627; Courier, 5 January 1838, page 2, “Memorial of James G. Holmes, relative to the preservation of Sullivan’s Island”; Southern Patriot, 10 January 1838, page 2, “The Bar and Harbour of Charleston.”

[23] Charleston Courier, 5 January 1838, page 2, “Memorial of James G. Holmes, relative to the preservation of Sullivan’s Island.”

[24] Southern Patriot, 14 January 1840, page 2, “(For the Courier.) Suggestions for the improvement of Charleston Harbor by James G. Holmes, Esq.”

[25] Courier, 17 January 1843, page 2, “Correspondence of the Courier”; Southern Patriot, 10 June 1844, page 2, “(Communication.) Hog Island Channel”; Courier, 18 June 1844, page 2, “Hog Island Channel”; Southern Patriot, 23 March 1846, page 2, “The Harbor Bill”;

[26] Courier, 30 April 1852, page 1, “Report on the Harbor of Charleston.”

[27] Charleston News and Courier, 22 August 1877, page 1, “The Harbor Bar.”

[28] News and Courier, 27 October 1880, page 1, “Matters in the City”; News and Courier, 8 December 1880, page 4, “The Harbor Commission”; “An Act creating a Harbor Commission for the Bay and Harbor of Charleston,” ratified on 24 December 1880, in Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Passed at the Regular Session of 1880 (Columbia, S.C.: James Woodrow, 1881), 398–99; “An Act to Amend an Act entitled ‘An Act creating a Harbor Commission for the Bay and Harbor of Charleston,’ approved 24 December 1880,” ratified on 19 December 1881, in Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Passed at the Regular Session of 1881–2 (Columbia, S.C.: James Woodrow, 1882), 604–8.

[29] See “An Act Creating a Harbor Commission for the Bay and Harbor of Charleston,” ratified on 24 December 1880, in Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Passed at the Regular Session of 1880 (Columbia, S.C.: James Woodrow, 1881), 398–99.

[30] News and Courier, 13 July 1881, page 1, City Council Proceedings of 12 July 1881; News and Courier, 14 July 1881, page 2, “Municipal Notices.”

[31] News and Courier, 15 October 1886, page 1, “Charleston’s Salvation.”

[32] See “An Act to establish a new Judicial and Election County from a portion of Charleston County, to be known as the County of Berkeley, to ascertain and define the boundaries of said Counties, and to provide for and fix the salaries of the county officers thereof,” ratified on 30 January 1882, in Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Passed at the Regular Session of 1881–2 (Columbia, S.C.: James Woodrow, 1882), 682–84.

[33] Governor John Calhoun Shepherd to Robert C. Gilchrist, 23 October 1886, CCRD book A38: 87–88. The deed of conveyance includes a plat of the property, surveyed at the request of R. C. Gilchrist in 1884.

[34] The business exploits of Robert C. Gilchrist and the plans for Seaview City are amply covered in the Charleston newspapers of 1874–94, and in the successive published volumes of the Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina during that same period. Robert C. Gilchrist conveyed 130 acres of Hog Island to Robert B. Gilchrist on 5 September 1899 (see CCRD C23: 359–60), and the latter’s widow, Georgette Relph Holmes Gilchrist (1886–1973), held the property until 1967.

[35] Charleston Evening Post, 19 April 1955, page 1, “U.S. Engineers Plan Major Changes For Charleston’s Historic Harbor.”

[36] Evening Post, 21 October 1955, page 1-B, “3 Dredges Cut New Channel”; Evening Post, 11 April 1956, page 1-A, “City Welcomes First Ship To Use New Harbor Channel.”

[37] See, for example, News and Courier, 6 October 1956, page 10-A, “Mosquitos Target of Army Engineers”; News and Courier, 11 December 1956, page 5-A, photo and caption, “Dragline Drains Mosquito Marshes in East Cooper Area”; Evening Post, 8 April 1957, page 2-A, “Spoil Area Drainage Work Is Completed”; News and Courier, 27 June 1963, page 1-B, “Citizens of Bayview Protest Spoil Smell.”

[38] News and Courier, 19 February 1963, page 1-B, “Harbor ‘Spring Cleaning’ Will Begin This Weekend”; News and Courier, 12 July 1963, page 1-B, “Millionaire’s Hideaway Sought For Spoil Area”; Evening Post, 19 September 1963, page 1-B, “State Leases Daniel Island for $1 A Year As Spoil Area”; Evening Post, 3 October 1963, page 1-B, “Bridge Approach Work Begins”; News and Courier, 31 January 1964, page 1-B, “Barr Says life of Port depends upon Spoil Areas”;

[39] Evening Post, 16 June 1971, page 1-A, “Park Commission Given Reprieve.”

[40] News and Courier, 19 May 1967, page 1-B, “Three Businessmen Purchase Hog Island”; Evening Post, 19 May 1967, page 5-B, “Hog Island Sold To Local Trio”; A plat of the 130-acre tract is recorded in CCRD Plat Book W: 25.

[41] News and Courier, 29 January 1970, page 1-B, “Storm Brewing Over Hog Island.”

[42] Evening Post, 16 June 1971, page 1-B, “Recreation Study: Plan is Comprehensive.”

[43] News and Courier, 23 February 1972, page 1-B, “Ownership of Hog Island Is Object of City Lawsuit.”

[44] Evening Post, 25 August 1972, page 1-A, “Hog Island Plan Cost: $60 Million”; News and Courier, 3 September 1972, page 1-A, “$88-Million Boost Seen In Hog Island.”

[45] News and Courier, 26 September 1972, page 12-B, “Ashley Cooper, Doing the Charleston” (continued from page 1-B); News and Courier, 10 April 1974, page 9-A, letters to the editor: “‘Patriots Point’ Defended.”

[46] Evening Post, 9 January 1973, page 1-A, “Delegation Hears Hog Island Plans”; News and Courier, 15 February 1973, page 16-A, “Finance Committee to Sponsor Museum.”

[47] News and Courier, 9 March 1974, page 1-A, “Patriot’s Point Authority Has Accord On 135 Acres”; Evening Post, 9 March 1974, page 1-A, “Site Accord Paves Way For Carrier.”

[48] News and Courier, 16 June 1975, page 1-A, “Charleston Welcomes ‘The Fighting Lady’”; News and Courier, 10 December 1975 (Wednesday), page 4-B, “Patriots Point, Tract Annexed by Mt. Pleas.”; News and Courier, 4 January 1976, page 1-A, “The Yorktown: ‘The Fighting Lady’ Draws Big Crowd At Opening.”

[49] News and Courier, 2 September 1977, page 1-A, “Patriots Point Board Studies Land, Ship Acquisition”; Evening Post, 9 November 1977, page 1-A, “Major Expansion Program Planned At Patriots Point.”

NEXT: Inventing the French Quarter in 1973

PREVIOUSLY: John Champneys and His Controversial Row, Part 2

See more from Charleston Time Machine