The Historic Landscape of the New Baxter-Patrick James Island Library

Processing Request

Processing Request

Charleston’s newest island library is situated in a quiet setting that belies the depth and drama of its long and colorful history. From Native-American stomping grounds to fertile plantation, from bloody battlefield, to civil rights success, the landscape of the new Baxter-Patrick James Island Library has quite a story to tell. Today we’ll surf through the pages of the past and follow a rich narrative that forms an important addition to our community’s shared history.

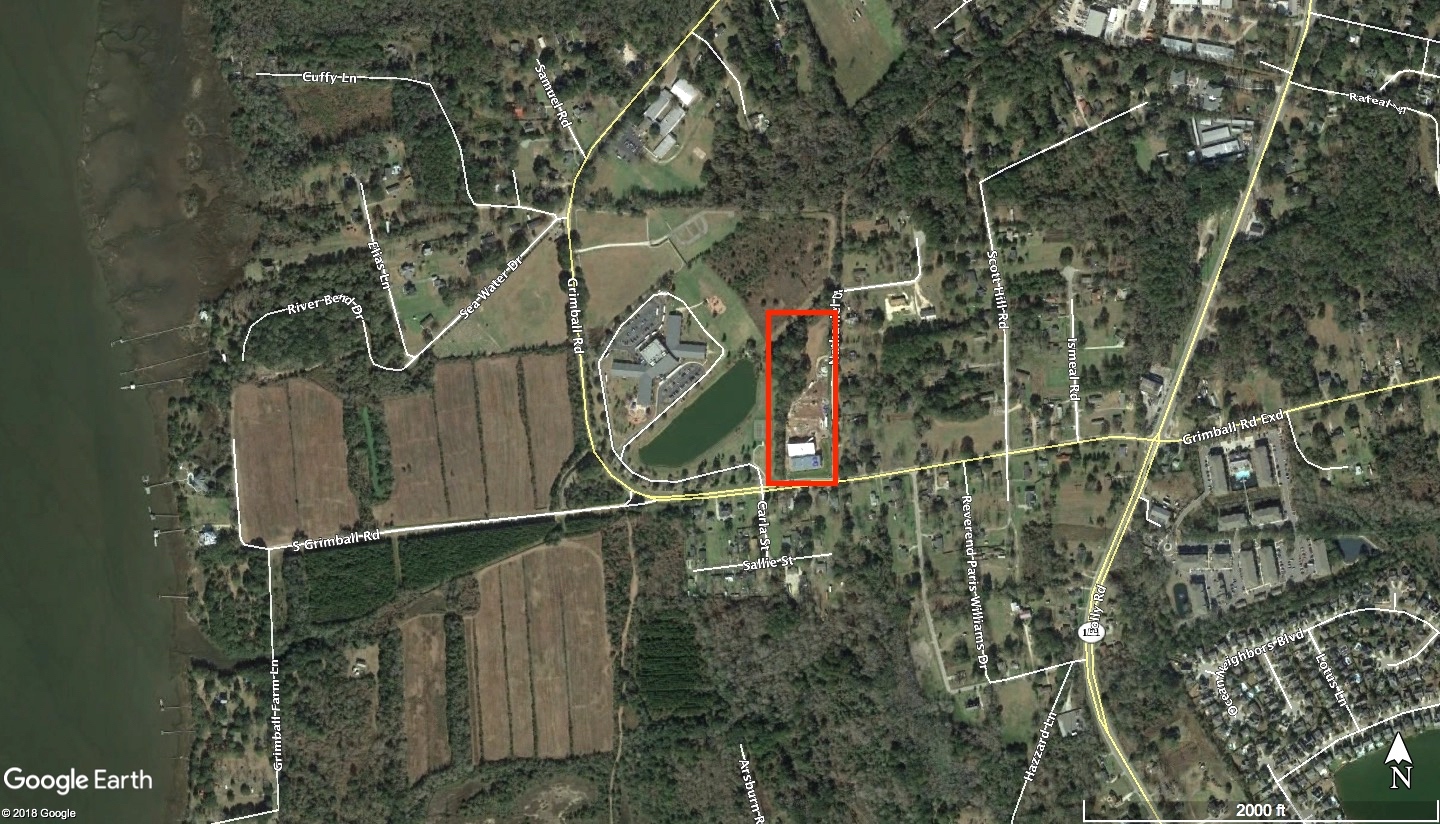

The Baxter-Patrick library on James Island is located on the north side of South Grimball Road, so named because the road cuts through an area that was once a large agricultural plantation owned by the Grimball family. In the early twentieth century, the Grimball plantation was a large tract encompassing approximately eleven hundred acres of high ground on the west side of James Island and more than one hundred acres of marshland along the banks of the Stono River. That large and irregularly-shaped property, which locals knew as Grimball Farm into the 1950s, was actually the consolidation of several smaller parcels that members of several different families had assembled over a period of more than two hundred years. The narrative of the occupation and use of this sprawling site therefore includes a number of separate stories for different parts of the thousand-acre tract, each of which once had its own distinct identity. Rather than trace the story of each parcel that formed part of Grimball Plantation at its peak size, I’m going to limit my focus to the history of the land under and around the new Baxter-Patrick library. That small site, containing just over six acres, was once part of the central core of the old Grimball property, and the paper trail of its story begins more than three hundred and fifty years ago.

Beginning in the 1500s, the first European explorers who visited the area now known as the Lowcountry of South Carolina encountered more than a dozen small but distinct groups of indigenous people living along the coastal plain. It’s difficult to pinpoint the precise territory of these various tribes, however, because they didn’t have permanent, fixed abodes. Instead, the indigenous people in this area followed a traditional pattern of seasonal migrations. The individual tribes living between the Savannah and Santee Rivers appear to have spent the spring and summer months living in semi-permanent camps near the sea coast, fishing and farming, and then moved farther inland during the autumn and winter months to hunt and to dress animal skins.[1]

Beginning in the 1500s, the first European explorers who visited the area now known as the Lowcountry of South Carolina encountered more than a dozen small but distinct groups of indigenous people living along the coastal plain. It’s difficult to pinpoint the precise territory of these various tribes, however, because they didn’t have permanent, fixed abodes. Instead, the indigenous people in this area followed a traditional pattern of seasonal migrations. The individual tribes living between the Savannah and Santee Rivers appear to have spent the spring and summer months living in semi-permanent camps near the sea coast, fishing and farming, and then moved farther inland during the autumn and winter months to hunt and to dress animal skins.[1]

In the years preceding the arrival of Europeans, James Island appears to have been the seasonal home of the Stono people who were known to reside to the east and west of the river that still bears their name. The earliest known documentary reference to this tribe appears in the report of a Spanish party that paid a visit to what is now Charleston harbor in 1609. They reported meeting the chiefs of several local tribes, including a group they called the “Ostano.” The first English explorers to encounter this tribe, in 1663, called them “Stonohs.” That name, recorded in a variety of spellings, has persisted for more than three and a half centuries.[2]

Like the other indigenous people residing here in the late seventeenth century, the population of the Stono people was relatively small. Early European settlers observed that each of these coastal tribes numbered around fifty bowmen or hunters, representing approximately two hundred individuals. Due to the paucity of surviving early documents, and the cultural bias of the early settlers, we have very little information about the culture of the Stono and the other indigenous groups that once inhabited the Lowcountry of South Carolina. All that remains of them now are fragments of hand-made pottery that have been found in local archaeological sites. More than one hundred Native American place names survive in the South Carolina Lowcountry, like the word Stono, but the rest of their indigenous languages have been lost forever.[3]

Immediately after arriving here in 1670, the English settlers established a central government that divided the local landscape into individual property holdings and began distributing them among the new arrivals. Successive land grants on James Island commenced along the island’s northern edge and proceeded southward. While the creation of new colonial homes and farms inevitably disrupted the seasonal habitations of the local indigenous peoples, the white settlers attempted to maintain amicable relations. The introduction of domesticated cattle and pigs apparently delighted the Stono, who incurred the wrath of the white settlers by hunting those animals as they did other wild game. As early as 1674, English colonists identified the Stono people as bad neighbors and began to use violence to chastise the tribe for their repeated trespasses. By 1682, one source estimated that the Stono tribe consisted of just sixteen bowmen—a sign that the entire tribe perhaps consisted of fewer that seventy people. The colonial pressure exerted on the indigenous population soon overwhelmed the Stono. In the spring of 1684, the cacique, or chief, of the Stono formally relinquished the tribe’s claim to lands on James and John’s Islands to the English settlers and agreed to confine themselves to what became known as Stono Island (now Seabrook Island).[4]

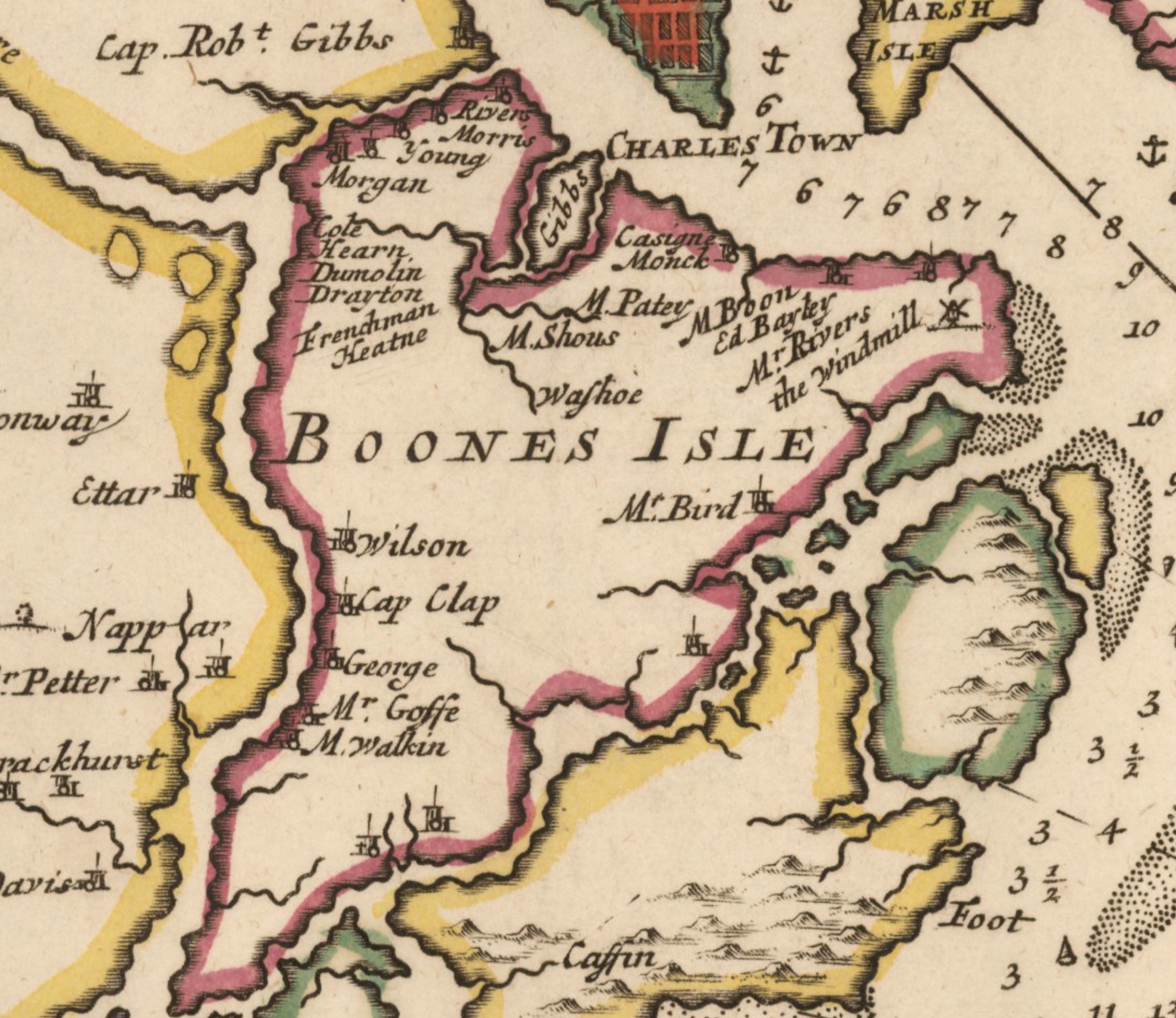

The earliest known record concerning the site of the new Baxter-Patrick James Island Library, which is located near the southwest corner of the island, dates from the autumn of 1683. On September 20th of that year, a man named Robert Goff (also spelled Goffe) received a grant for four hundred acres situated along the east side of the Stono River. Mr. Goff had been in the area since at least 1673, so it’s possible that he settled on the land in question before it was formally granted to him.[5] The details of his tenure at this site are now lost, but it appears that the property remained in the Goff family into the early years of the eighteenth century. A map of Carolina published in London around the year 1695 (and reprinted in Amsterdam in 1696) includes a view of James Island (then called “Boone’s Isle”) that includes the name “Mr. Goffe” in the lower left hand side of the island.

The earliest known record concerning the site of the new Baxter-Patrick James Island Library, which is located near the southwest corner of the island, dates from the autumn of 1683. On September 20th of that year, a man named Robert Goff (also spelled Goffe) received a grant for four hundred acres situated along the east side of the Stono River. Mr. Goff had been in the area since at least 1673, so it’s possible that he settled on the land in question before it was formally granted to him.[5] The details of his tenure at this site are now lost, but it appears that the property remained in the Goff family into the early years of the eighteenth century. A map of Carolina published in London around the year 1695 (and reprinted in Amsterdam in 1696) includes a view of James Island (then called “Boone’s Isle”) that includes the name “Mr. Goffe” in the lower left hand side of the island.

At some point in the early years of the eighteenth century, a large portion of Mr. Goff’s four hundred acres passed into the hands of a man named Jonathan Evans. The paucity of surviving records from this era of South Carolina history make it difficult to confirm the identity of this man, the date of his arrival in the colony, and the manner in which he acquired the property in question, but I did find one very intriguing potential clue. On September 13th, 1701, a mariner named Jonathan Evans came to Charleston to take advantage of a Royal proclamation offering amnesty to pirates who promised to abandon that illegal lifestyle. At a formal audience with South Carolina Governor James Moore, Jonathan Evans confessed that he had been a crew member aboard the Adventure galley, sailing under the infamous Captain William Kidd, and had until recently followed a “wicked pyractycall course of life.” In return for a full pardon, Evans renounced that pernicious lifestyle and promised to be a loyal, law-abiding citizen in the future.[6]

The scarcity of detailed records from the early eighteenth century render it practically impossible to determine whether our Jonathan Evans of James Island was an ex-pirate or simply another immigrant of the same name. Nevertheless, we know that someone named Jonathan Evans settled on the east bank of the Stono River, raised a family, and acquired a small number of enslaved laborers to help him work the land. Enslaved people of African descent formed the majority of South Carolina’s non-Indian population by the year 1708, and their presence of James Island is documented is scores of surviving legal documents like probate records and inventories of estates.

Jonathan Evans of James Island, for example, died intestate in 1728, and his widow, Elizabeth, obtained permission from the government to administer his estate. An inventory of Jonathan Evans’s plantation on James Island, dated November 13th, 1728, includes some household furniture, a number of agricultural tools, seven horses, thirty-four head of cattle, eighteen hogs, seventeen sheep, one yoke of oxen, and nine enslaved people Mrs. Evans called Pompey, London, Cuffee, Will, Jack, Ann, Jane, Phillis, and Sarah. From this documentary evidence, it would appear that Mr. Evans had been raising livestock and probably growing provision crops like corn and peas. We can also infer that the enslaved men and women living on this small plantation were performing the bulk of the labor. We know nothing about their lives, or where they might be buried, but it seems likely that their descendants continued to work the Evans land for at least another generation.[7]

The property under and around the new James Island library descended from Jonathan Evans to his eldest son, also named Jonathan Evans (died 1746). At some point in the year 1741, the younger Evans sold 265.5 acres of his James Island property, including the library site, to John Mathews.[8] Mr. Mathews later acquired an additional forty acres from Jonathan’s brother, Samuel Evans, and then sold the combined 305.5 acres to his southern neighbor, George Rivers, in late September 1758.[9] Mr. Rivers, who resided here until his death in 1785, acquired further acreage to the north and had the property in question re-surveyed in 1777. The surviving plat created at that time shows a large, mostly-rectangular tract of 331 acres of high ground and a quantity of marshland fronting the Stono River. Unfortunately for us, this plat doesn’t show any detail or remarkable physical features besides a “small creek” at the southwestern edge of the property that still flows today near the southwestern end of modern South Grimball Road. Using this feature as a geographic reference point, we can deduce that the new Baxter-Patrick Library is located just a bit to the right of the center of Mr. Rivers’s plantation.[10]

The property under and around the new James Island library descended from Jonathan Evans to his eldest son, also named Jonathan Evans (died 1746). At some point in the year 1741, the younger Evans sold 265.5 acres of his James Island property, including the library site, to John Mathews.[8] Mr. Mathews later acquired an additional forty acres from Jonathan’s brother, Samuel Evans, and then sold the combined 305.5 acres to his southern neighbor, George Rivers, in late September 1758.[9] Mr. Rivers, who resided here until his death in 1785, acquired further acreage to the north and had the property in question re-surveyed in 1777. The surviving plat created at that time shows a large, mostly-rectangular tract of 331 acres of high ground and a quantity of marshland fronting the Stono River. Unfortunately for us, this plat doesn’t show any detail or remarkable physical features besides a “small creek” at the southwestern edge of the property that still flows today near the southwestern end of modern South Grimball Road. Using this feature as a geographic reference point, we can deduce that the new Baxter-Patrick Library is located just a bit to the right of the center of Mr. Rivers’s plantation.[10]

The paper trail for the land itself provides much useful information, but it doesn’t tell us how the Mathews and Rivers families used the property, what they were growing, or who was doing the labor on the plantation. To find answers to these questions, we have to look farther afield, and into the future. A newspaper description of the property, published in December 1786, for example, noted that Mr. Rivers’s plantation on James Island included “an excellent dwelling-house, a good barn, negro houses, and other necessary out houses, all in good repair.”[11] The precise location of these buildings in not revealed in contemporary documents, but they might have been identical to the structures depicted on a plat of this property made by members of the Union Army who briefly commandeered the plantation in the summer of 1862. That plat, which is found among the collections of the National Archives of the United States, shows the master’s house a few hundred feet east the Stono River, at the western end of what is now South Grimball Road, with a barn and several outbuildings located immediately to the northeast. To the northwest of the big house is a row of eleven small buildings standing along the edge of the river, all of which are labeled “negro quarters.”[12] In short, the people living on this plantation were clustered along the western edge of the property, adjacent to the Stono River, while the agricultural fields and pastures they tended occupied the more inland parts of the landscape.

Later records indicate that during the third quarter of the eighteenth century, this Rivers plantation on James Island was growing corn and peas for provisions and raising a fair number of cattle and hogs as well. The plantation’s inventory of tools included several fishing seines, casting nets for shrimping, a fishing boat with four oars, and a “large pettiauger” [sic] with multiple oars to transport goods between the plantation and the port of Charleston.[13] Sited next to a brackish river, the land was not especially suited to the cultivation of rice, but it seems likely that John Mathews and later George Rivers would probably have grown indigo on this property, as many of their neighbors did. You might remember that I discussed indigo cultivation in the South Carolina Lowcountry recently in Episode No. 124. I noted that some planters constructed indigo-processing vats out of bricks and mortar, but most of these necessary structures were built like water-tight boxes using cypress and cedar planks. If the Mathews or Rivers families built wooden indigo vats on this property around the middle of the eighteenth century, they might have dismantled them and used the materials for heating and cooking during the dark days of the American Revolution.

The site of the new library on James Island was not directly involved in any military action during the American Revolution, which commenced in 1775 and ended in 1783. The British Army landed thousands of troops on the northern part of James Island in early 1780 and made camp before crossing the Ashley River to the Charleston peninsula, but the plantation belonging to George Rivers was on the southern fringes of their destructive path. Nevertheless, we can assume with some confidence that British foraging parties scoured the entire island in search of cattle, hogs, and vegetables of all kinds to feed the hungry troops, as well as firewood to cook their meals. The residents of the Rivers plantation, both free and enslaved, were likely terrified by these foraging raids, but it’s possible that some members of the enslaved population fled the plantation to seek protection and freedom within the British camp.[14]

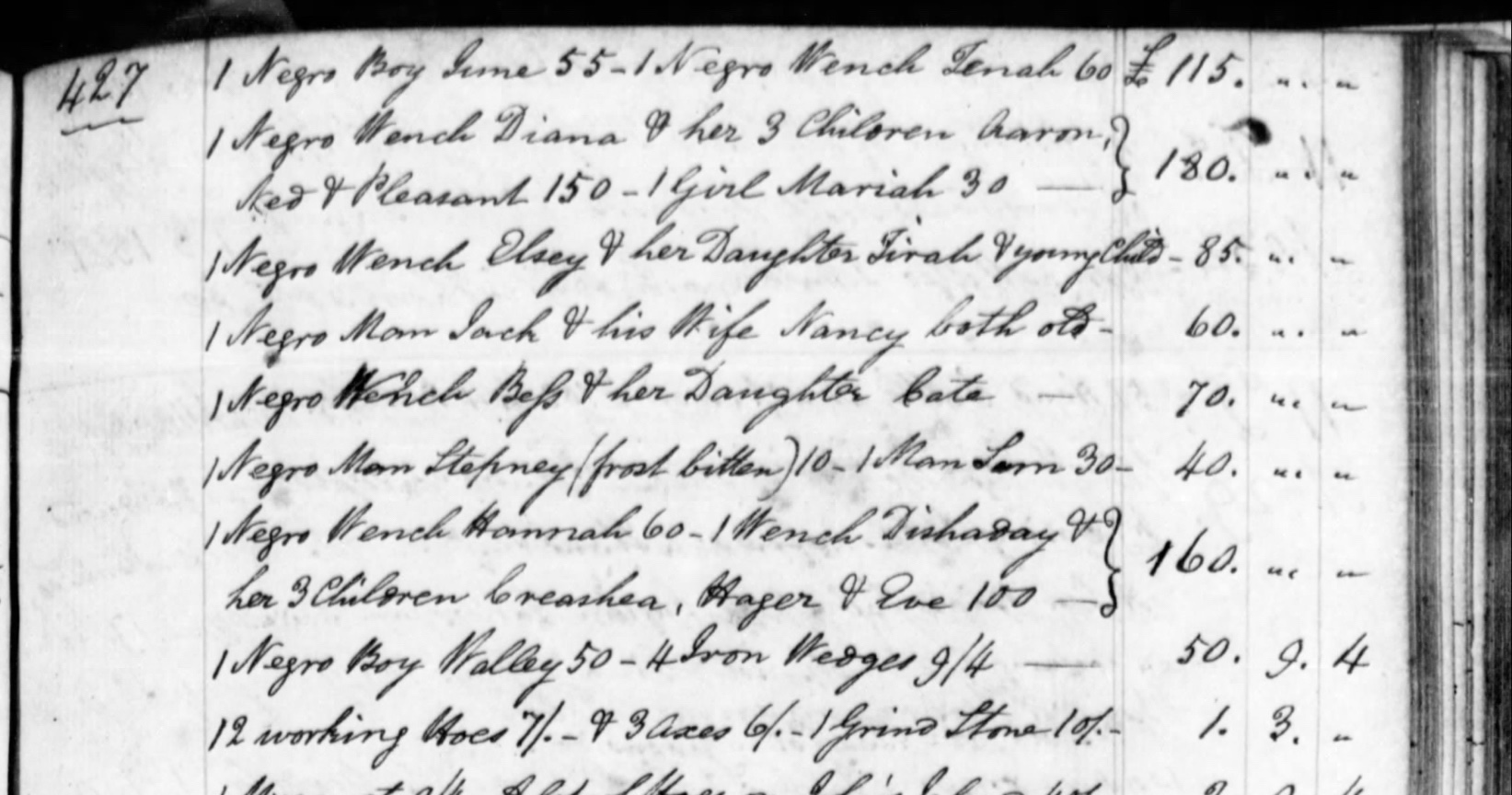

George Rivers, the former owner of the property around the new James Island library, died at his home facing the Stono River in early January 1785, in the 63rd year of his age. More than a year later, in the spring of 1786, his executors and neighbors gathered on the plantation to make an inventory of the chattel (moveable) property and to assign a monetary value to everything and everyone. An advertisement for the sale of Rivers’s estate mentioned “a stock of cattle, two horses, hogs, household furniture, plantation tools, a pettiauger [sic], a riding chair, and sundry other articles,” but no enslaved people.[15] Those laborers—the descendants of people brought here in chains from Africa—were apparently destined to remain on the land, which was to remain within the hands of a Rivers family heir for another generation.

Fortunately for us, the itemized inventory of George Rivers’s estate, now held at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, also includes the names of thirty-nine enslaved people and their familial relationships: Choice and his wife Laffon and their three children named Dido, young Choice, and Sue; Wappin and his wife Sarah and their children London, Hannah, and Sampson; Saundy (perhaps Laundy) and his wife Phebe and their child Rittah; Diana and her three children Aaron, Ned, and Pleasant; Elsey and her daughter Tirah, and a young unnamed child; Jack and his wife Nancy (“both old”); Bess and her daughter Cate; Dishaday and her three children Creashea, Hager, and Eve; and eleven individuals named Tomb, Pendah, Sue, Toney, June, Tenah, Mariah, Stepney (“frost bitten”), Sam, Hannah, and Walley.[16]

In his last will and testament, George Rivers bequeathed the bulk of his estate, including his plantation on James Island, to his granddaughter, Elizabeth Mary Wilson. Since she was a young girl at the time of George’s death, Elizabeth’s father, John Wilson, managed the property on her behalf until she married. In December of 1786, he advertised to lease the plantation on James Island, along with its houses and out buildings, “being the same where Mr. Rivers in his life-time resided.”[17] To whom the property was leased, how long it was leased, and how they used the land are questions unanswered by surviving records. Elizabeth Mary (“Eliza”) Wilson married Mr. James Stanyarne of St. Paul’s Parish on Christmas Day, 1794, at which time her James Island plantation came under the legal control of her husband. I haven’t found any records that document how James Stanyarne used the property, so we don’t know if they continued to lease the land or if the young Stanyarne family resided at the old house facing the Stono River.[18]

In his last will and testament, George Rivers bequeathed the bulk of his estate, including his plantation on James Island, to his granddaughter, Elizabeth Mary Wilson. Since she was a young girl at the time of George’s death, Elizabeth’s father, John Wilson, managed the property on her behalf until she married. In December of 1786, he advertised to lease the plantation on James Island, along with its houses and out buildings, “being the same where Mr. Rivers in his life-time resided.”[17] To whom the property was leased, how long it was leased, and how they used the land are questions unanswered by surviving records. Elizabeth Mary (“Eliza”) Wilson married Mr. James Stanyarne of St. Paul’s Parish on Christmas Day, 1794, at which time her James Island plantation came under the legal control of her husband. I haven’t found any records that document how James Stanyarne used the property, so we don’t know if they continued to lease the land or if the young Stanyarne family resided at the old house facing the Stono River.[18]

The enslaved people living on the James Island property probably continued to grow corn and peas for their own use, and probably raised beef cattle, dairy cows, and hogs as well. The cultivation of indigo declined across South Carolina in the wake of the American Revolution, however, because the British bounty that had made the crop profitable disappeared during the war. In the early 1790s, planters across the Lowcountry were experimenting with new and more profitable crops, including cotton. People here had been growing small amounts of cotton for generations, for home use, but cotton was not very profitable because it was difficult to remove the seeds from the boll. With the mechanical refinement of the hand-operated cotton gin in the early 1790s, however, cotton immediately became very profitable, and many South Carolinians started planting it in large quantities. Local planters noticed that the climate along the coastal sea islands was especially suited to the cultivation of a special variety of cotton (Gossypium barbadense) that produced longer, softer fibers that commanded a higher price at market. During the era of the Staynarne’s ownership, planters across James Island and beyond committed great resources to the cultivation of this luxurious plant that became known as “Sea Island cotton.”[19]

In late September 1810, James and Eliza Stanyarne sold the James Island plantation they had inherited from George Rivers to Robert James Turnbull (1774–1833). Mr. Turnbull was the son of Dr. Andrew Turnbull, a Scottish adventurer who had earlier launched the unsuccessful colony of New Smyrna in Florida. The younger Mr. Turnbull had grown up in and around Charleston and was very active in local politics here during the 1820s. Although he seems to have spent much of his time in urban Charleston, Robert James Turnbull did add more than 200 acres to his James Island plantation, and probably continued the cultivation of Sea Island cotton during his tenure of the property.[20]

A few days before his death in June 1833, Robert James Turnbull sold his James Island plantation to a neighbor, Paul Chaplin Grimball (1788–1864). Mr. Grimball, who also owned a large plantation on John’s Island, directly across the Stono River, had earlier purchased a tract of 250 acres immediately south of Robert J. Turnbull’s land. By acquiring Mr. Turnbull’s plantation, Paul C. Grimball gained a further 624 acres of high land, including the site of the new library, as well as a great deal of marshland and at least three small islands in the Stono River (Battery Island, Horse Island, and Hallooing Island). Although the surviving records tell us much about the character of the land, I haven’t found any documents that mention the number and identity of the enslaved people who lived and died at this site and worked the soil to generate wealth for the Grimball family. That archival silence is broken, at least partially, by information gathered by the United States Census Bureau in 1850.

The familiar census records list the names and other information about home owners and residents across the country, but prior to 1865 the census did not record much information about the enslaved people who formed a significant portion of the population in the Southern states. For the census of 1850, the federal government created a separate schedule of “slave inhabitants” to record the age and gender of enslaved people under the names of their respective owners. The September 1850 “slave schedule” for St. Andrew’s Parish shows that Paul C. Grimball’s plantation on James Island was home to 110 enslaved people, including sixty-five men and boys and forty-five women and girls, whose ages ranged from as young as one month to eighty years old. Unfortunately for us, the census did not record their names or familial relationships.[21]

The familiar census records list the names and other information about home owners and residents across the country, but prior to 1865 the census did not record much information about the enslaved people who formed a significant portion of the population in the Southern states. For the census of 1850, the federal government created a separate schedule of “slave inhabitants” to record the age and gender of enslaved people under the names of their respective owners. The September 1850 “slave schedule” for St. Andrew’s Parish shows that Paul C. Grimball’s plantation on James Island was home to 110 enslaved people, including sixty-five men and boys and forty-five women and girls, whose ages ranged from as young as one month to eighty years old. Unfortunately for us, the census did not record their names or familial relationships.[21]

The United States census of 1850 also initiated several non-population schedules, including a record of agricultural activity on farms and plantations across the country. According to the agricultural schedule for St. Andrew’s Parish, dated “August & September,” P. C. Grimball owned 600 acres of “improved” land, 755 acres of “unimproved” land, valued at $26,000. The stock included ten horses, fifty milk cows, twenty-six “other cattle,” fourteen oxen, thirty sheep, and forty hogs, all valued at $1,000. In the previous twelve months, the enslaved people laboring on this plantation had produced 1,200 bushels of Indian corn, 1,900 pounds of rice, eleven tons of ginned cotton (compressed into fifty-five bales weighing 400 pounds each), 4,000 bushels of sweet potatoes, 550 pounds of butter, fifty pounds of wool, and five bushels of clover seed for their pasture land. These were busy, hardworking people for sure.[22]

Paul Chaplin Grimball, the owner of the land and the laborers, divided his time between his plantations on James and John’s Islands, which were nearly facing each other on opposite sides of the Stono River. In November 1851, he purchased an additional 160 acres from a neighbor, Henry Bailey, to extend his James Island property further inland. A few years later, Mr. Grimball’s son, Thomas Hanscomb Grimball (1824–1864), married Mr. Bailey’s daughter, Sarah Bailey (1839–1914), at which time the elder Grimball retired to John’s Island and gave his James Island plantation to the young couple.[23]

When the United States Census Bureau came calling again in 1860, little had changed for the enslaved people who lived in the row of small wooden shacks along the edge of the Stono River. According to the 1860 schedule of “slave inhabitants,” Thomas H. Grimball’s plantation on James Island in St. Andrew’s Parish was home to ninety-three enslaved people, including forty-eight men and boys and forty-five women and girls, whose ages ranged from as young as two months to seventy years old. The agricultural census of 1860s also recorded the presence of nine horses, three mules, sixty milk cows, forty-five “other cattle,” thirty-three sheep, and fifty hogs. In the previous twelve months, the enslaved people laboring on this plantation had produced 1,200 bushes of Indian corn, nearly seven tons of ginned cotton (compressed into thirty-four bales weighing 400 pounds each), 200 pounds of wool, 100 bushel of peas and beans, 800 bushels of sweet potatoes, 500 pounds of butter, and twelve tons of hay. The nature of the crops had changed a bit in the course of a decade, but the people held in bondage by the Grimballs continued to demonstrate their agricultural prowess on the eve of the Civil War.[24]

The disastrous war between the North and South that commenced in April 1861 had little impact on the Grimball plantation on James Island during its first year. Following the Union victory at the Battle of Port Royal in November 1861, however, Federal troops based in the Beaufort area began creeping northward and preparing to attack Charleston. By May 1862, Union gunboats were venturing up the Stono River and harassing Confederate outposts on James and John’s Island, as well as civilian plantations. Confederate officials ordered the immediate evacuation of all non-combatants from James Island on May 29th, by which time many had already packed up and left. The Grimball family, like their neighbors, might have left behind one servant to guard the property, but everyone else packed up a few belongings in haste and fled towards the interior of South Carolina.[25]

Days later, Union soldiers disembarking from steam-powered gunboats in the Stono River overran the plantations on the west side of James Island. Members of the 97th, 67th and 45th Pennsylvania Regiments, the 3rd New Hampshire Regiment, Hamilton’s Regular Army Battery, and the 3rd Rhode Island Battery all camped at Grimball’s plantation and used the vacant big house as their headquarters. In great haste, engineers erected a lookout tower and strengthened their position with an encircling line of earthen fortifications. From this camp, the soldiers pushed eastward nearly two miles and joined ranks with other Union troops to attack the Confederate battery at Secessionville on June 16th, 1862. The assault was a tactical failure, and the Union troops retreated to bury their dead among the weedy fields of corn and cotton. After leaving behind dozens of marked and unmarked graves on the Grimball property, the United States forces withdrew from James Island in early July.[26]

Although the Union Army’s campaign on James Island in the summer of 1862 ended in retreat, soldiers in blue returned to Grimball’s plantation on the banks of the Stono River to attempt the same offensive maneuvers in the summer of 1863. In mid-July of that year, the untested recruits forming the Massachusetts 54th regiment of African-American troops fought their first battle at Grimball’s Landing (as seen in the movie, Glory). Days later, they pushed eastward and attacked Battery Wagner on Morris Island with disastrous results. Repulsed a second time in as many years, Union troops again returned to Grimball’s plantation on James Island in the summer of 1864 and dug in for the final push. At the end of the Civil War in the spring of 1865, authorities representing the United States government seized the Grimball property and all of the other former slave-holding plantations in the area.

It’s unclear whether any of the enslaved people affiliated with this plantation returned at any time before the end of the war, but it appears that the white members of the Grimball family did not venture back to the island. Paul Chaplin Grimball, who had purchased the property in 1833, died in Sumter District, South Carolina, in August 1864. His son, Thomas Hanscomb Grimball died in Barnwell District in November 1864.[27] In the immediate aftermath of the war, an unknown number of the people formerly enslaved on this and neighboring plantations returned to the island and began to farm the land, though on a much smaller scale. While the government encouraged the freedmen, as they were called, to stake out small farms for their own use, federal authorities also bowed to pressure from local planters seeking to reclaim their large and once valuable tracts. Sometime between 1866 and 1868, Sarah Bailey Grimball, the widow of Thomas H. Grimball, successfully petitioned to have her James Island property restored. For the time being, she held in the property in trust for her only son, Henry Bailey Grimball (1860–1943), who was just an infant when the big war began.[28]

The post-war years were a chaotic time throughout the Lowcountry of South Carolina, as people slowly learned to cope with the daily intersections of traditional ways and new-fangled realities. The Grimball family apparently rented small tracts of farm land on James Island to the families of freedmen and freedwomen, while Sarah and her young son Henry Grimball lived in downtown Charleston.[29] At some point in the 1870s, African-American families residing on or around the old Grimball place on James Island began burying their loved ones and marking their graves in a cemetery located in what was once the center of the former plantation’s agricultural landscape. That burial site, which still exists today, might have been in use long before the Civil War, but it did not appear on any known map or plat of the property before the 1950s. We might never know the date of the earliest burials at this Grimball graveyard, as it was once called, but we do know that several hundred people—the descendants of enslaved people—were buried here between the 1870s and the 1990s.

By the time of the Federal Census of 1880, Henry B. Grimball was a twenty-year-old adult who had claimed his inheritance on James Island. The census described him as a “cotton planter” living on the island with his mother, Sarah, though it’s not clear how many acres they were farming. The 1880 census of agricultural productions is very difficult to read on microfilm, and I can’t find Henry Grimball. That record includes Sarah Grimball, however, who was cultivating just thirty acres of corn and seventy-five acres of cotton, along with some cows, pigs, and chickens. This production was a far cry from the large crops harvested by enslaved laborers before the war, but it seemed that most of the land had been rented out to local freedmen who lived on and around the old plantation.[30]

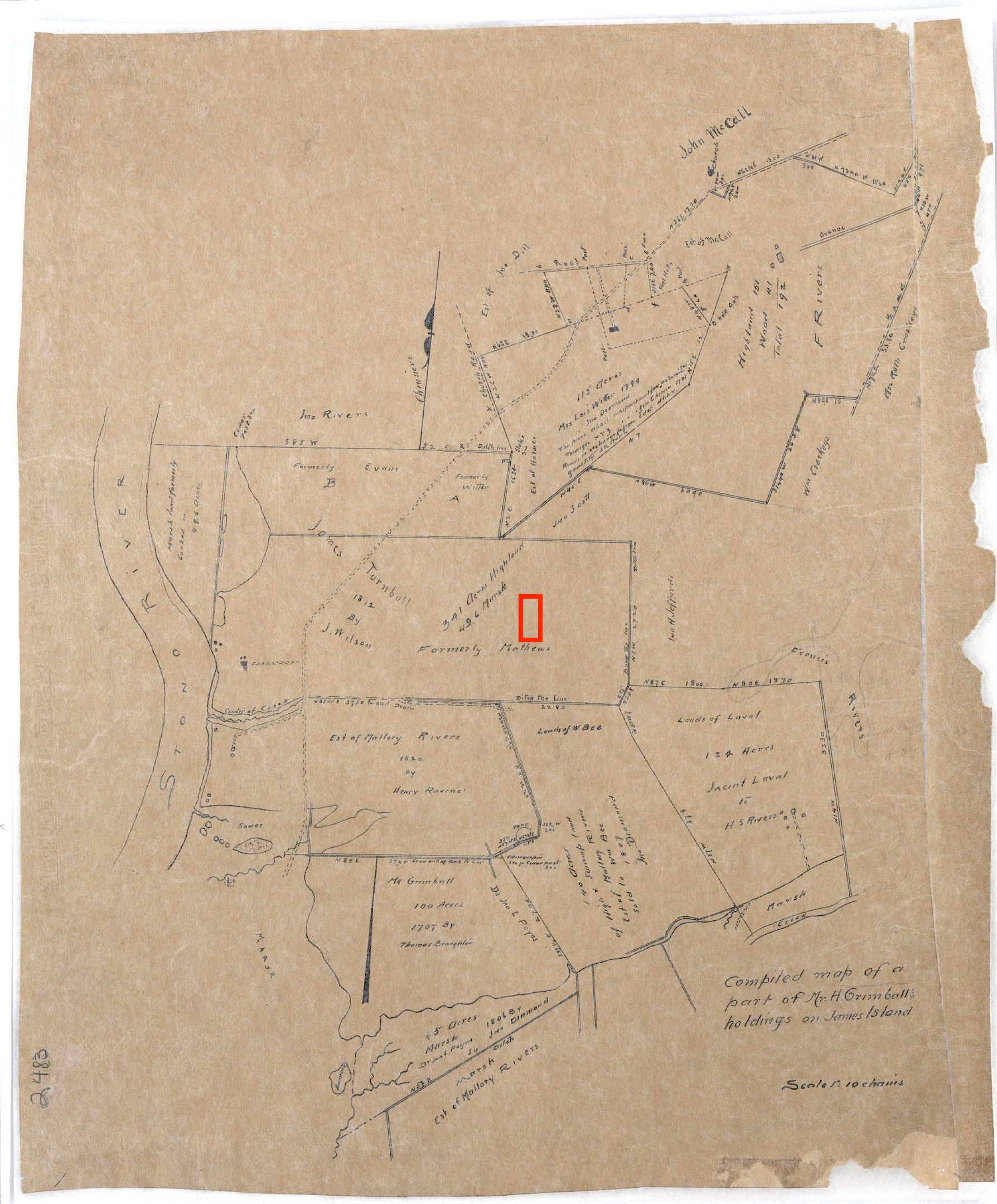

Henry B. Grimball married Loula (aka Lulu) Habenicht (1864–1952) of Charleston in February 1885. Over the next thirty-odd years, the family continued to grow Sea Island cotton in respectable quantities, as well as other vegetables, eggs, and butter for home consumption. In 1902, Henry and his mother, Sarah, divided between themselves the remaining Grimball property on James Island. Henry kept the majority of the land, but Sarah held title to more than 150 acres “north of the dam” that once ran parallel to and a bit south of modern South Grimball Road. Sarah Grimball’s tract thus included the present site of the Grimball cemetery, now called Evergreen Cemetery, and the new Baxter-Patrick Public Library. At some point around the turn of the twentieth century, perhaps after the death of Sarah Bailey Grimball in 1914, Henry commissioned a surveyor to create a plat of his land on James Island. That undated plat depicts an irregularly-shaped swath of lands on the east side of the Stono River, amounting to over 1,100 acres of high ground and lots of marshland, but it does not illustrate the African-American cemetery located very near the center of the property.[31]

Henry B. Grimball married Loula (aka Lulu) Habenicht (1864–1952) of Charleston in February 1885. Over the next thirty-odd years, the family continued to grow Sea Island cotton in respectable quantities, as well as other vegetables, eggs, and butter for home consumption. In 1902, Henry and his mother, Sarah, divided between themselves the remaining Grimball property on James Island. Henry kept the majority of the land, but Sarah held title to more than 150 acres “north of the dam” that once ran parallel to and a bit south of modern South Grimball Road. Sarah Grimball’s tract thus included the present site of the Grimball cemetery, now called Evergreen Cemetery, and the new Baxter-Patrick Public Library. At some point around the turn of the twentieth century, perhaps after the death of Sarah Bailey Grimball in 1914, Henry commissioned a surveyor to create a plat of his land on James Island. That undated plat depicts an irregularly-shaped swath of lands on the east side of the Stono River, amounting to over 1,100 acres of high ground and lots of marshland, but it does not illustrate the African-American cemetery located very near the center of the property.[31]

When the boll weevil destroyed the tradition of Sea Island cotton in the early 1920s, Henry Grimball and his neighbors turned to truck farming, in which they raised crops like tomatoes, peaches, and melons to sell at local markets.[32] The use of gasoline-powered vehicles to transport goods to market was facilitated in the early 1930s by the creation of Folly Road down the center of James Island, and by the eastward extension of Grimball Road (now called South Grimball Road) to connect the Grimball farm with that new trans-island thoroughfare.[33]

Following Henry Grimball’s death in 1943, and that of his widow, Lulu, in 1952, their children subdivided a tract of 150 acres in the center of the old Grimball plantation that Sarah Bailey Grimball had claimed in the early twentieth century. A plat of that division, created in 1953, shows sixteen parcels labeled alphabetically “A” through “P,” located on both sides of South Grimball Road, as well as a “negro cemetery” sandwiched between parcels “L” and “M.” The Grimball heirs sold parcel “M,” containing just over six acres on the north side of the road, to the Charleston County School District in January 1963. Thirteen months later, on February 2nd, 1964, county officials and local residents gathered to dedicate Baxter-Patrick Elementary School. It was named for two retired school principals, Mrs. Nan C. Baxter (died 2 Sept. 1966) and Mrs. Anna S. Patrick (died 10 June 1973), who are remembered as the first black school teachers on James Island during the era of segregated education. Baxter-Patrick school continued to serve the community until it was closed in the late 1990s. The disused building was demolished in 2011, and in June 2015, Charleston County Council selected the grounds of the former school as the site of a state-of-the art public library for the people of James Island.[34]

When Charleston County commenced planning its new library on South Grimball Road, Councilwoman Anna B. Johnson spoke passionately about the local community’s desire to ensure that the construction project did not disturb or destroy the adjacent African-American cemetery that had been in use for at least a century and a half. Following a series of meetings and site visits with local stakeholders, representatives of Charleston County government and CCPL committed to a plan that would not only protect the burial ground, but also connect the graves and their history with the fabric of the new library. Using illustrated signage both inside and outside the new building, the story of James Island, the Grimball plantation, and the sacred ground now known as Evergreen Cemetery is proudly displayed to visitors. The cemetery is a tangible reminder of the site’s plantation legacy, while the new library’s name is a nod to the site’s more recent history.

When Charleston County commenced planning its new library on South Grimball Road, Councilwoman Anna B. Johnson spoke passionately about the local community’s desire to ensure that the construction project did not disturb or destroy the adjacent African-American cemetery that had been in use for at least a century and a half. Following a series of meetings and site visits with local stakeholders, representatives of Charleston County government and CCPL committed to a plan that would not only protect the burial ground, but also connect the graves and their history with the fabric of the new library. Using illustrated signage both inside and outside the new building, the story of James Island, the Grimball plantation, and the sacred ground now known as Evergreen Cemetery is proudly displayed to visitors. The cemetery is a tangible reminder of the site’s plantation legacy, while the new library’s name is a nod to the site’s more recent history.

After more than a year of construction, the Baxter-Patrick James Island Library opened to the public on Saturday, November 2nd, 2019. The library’s modern styling and high-tech equipment drew cheers from visitors young and old, but the illustrated pathway linking the library and its parking lot to the old cemetery provided an unexpected treat for many. Surrounded by a new fence and informed by handsome signage, the cemetery invites visitors to wander among the stately live oaks and contemplate the long and troubled history of James Island. The people buried here include men and women who survived the era of slavery and lived to enjoy a moment of freedom, as well as the descendants of those hard-laboring people who witnessed the painful birth of the colonial plantations and the dark days of both the American Revolution and the Civil War.

The Baxter-Patrick James Island Library will serve for many years to come as a comfortable and welcoming place to foster learning and growth in our community. When you visit, and you really must visit, I implore you to reserve a few minutes to walk along the short pathway linking the library and the cemetery to peruse the colorful historical panels. Unlatch the gate and tread respectfully along the path leading into the burial ground. Look up at the live oak canopy, and cast your eyes around the evergreen landscape. This place, the people and the history beneath your feet represent a genuine James Island time machine.

[1] For an excellent overview of early Native American history in the Lowcountry, see Gene Waddell, Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry, 1762–1751 (Columbia, S.C.: Southern Studies Program, University of South Carolina, 1980), 329–32.

[2] Waddell, Indians, 304–6.

[3] Waddell, Indians, 8–15, 23–33.

[4] Waddell, Indians, 304–7.

[5] A memorial filed by George Rivers in 1760 traced his James Island property back to grants issued to Robert Goff and Richard Batten, but Batten’s grant was to the north of Goff’s property and the library site. See South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Memorial Books, Vol. 7: 324–25. Robert Goff appeared as a witness to a June 1673 conveyance in Charleston; see Susan Baldwin Bates and Harriott Cheves Leland, eds., Proprietary Records of South Carolina, Volume Two: Abstracts of the Records of the Register of the Province, 1675–1696 (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2006), 32.

[6] SCDAH, Records of the Secretary of the Province, book 1694–1705, page 398; also transcribed in WPA transcription volume No. 54 (1694–1704), pages 453–54, at CCPL’s South Carolina History Room. For more information on Capt. Kidd, see Shirley Carter Hughson, The Carolina Pirates and Colonial Commerce, 1670–1740 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1894). One Jonathan Evans and his wife, Marie or Mary, baptized several children in Christ Church Parish (now Mount Pleasant) in the 1710s; see, for example, Mabel L. Webber, ed., “The Register of Christ Church Parish,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 18 (January 1917): 53. One Jonathan Evans died ca. 1711–12 leaving a will and inventory of his estate, neither of which survives today; see Charles H. Lesser, South Carolina Begins: The Records of a Proprietary Colony, 1663–1721 (Columbia: South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1995), 341.

[7] On 11 September 1728, Arthur Middleton, president of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina (and acting governor of the province), granted letters of administration to Elizabeth Evans, widow of Jonathan Evans of St. Andrew’s Parish, who “lately died intestate.” The following day, Middleton granted Elizabeth Evans letters of guardianship for her “six infant children the eldest of whome [sic] doth not exceed 13 years of age,” all of whom were the children of the late Jonathan Evans. See WPA transcription volume No. 76A, pages 344–46, at CCPL. The inventory of his estate, dated 13 November 1728, was appraised by George Rivers, William Wilkins, Thomas Heyward, William Spencer, and Thomas Stanyarne, and can be found at CCPL in WPA transcription volume No. 76B, pages 715–16.

[8] The conveyance from Jonathan Evans Jr. to John Mathews is not recorded among the surviving records of the Charleston County Register of Deeds (hereafter RoD), but is mentioned in a renunciation of dower made by Elizabeth Evans, wife of Jonathan Evans Jr., to John Mathews, which was recorded on 4 December 1741. See SCDAH, Renunciation of Dower Books, volume 1739–1741, page 114.

[9] John Mathews and Sarah, his wife, to George Rivers, lease and release for £4,200 South Carolina currency, 29–30 September 1758, recorded in RoD book TT, pages 494–500. On 22 October 1760, George Rivers filed a memorial for this 305.5 acres that recites an incomplete chain of title back to Robert Goff’s grant of 1683; see SCDAH, Memorial Books, volume 7, pages 324–25.

[10] The plat by James Rivers, deputy surveyor, is dated 7 February 1777, and is annexed to an 1810 conveyance of the property to Robert J. Turnbull (see below).

[11] Charleston Morning Post, 2 December 1786.

[12] “Survey & plat by Lt. Brooks, Vol. Engrs., June 14, 1862,” National Archives, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Records Group 77.2, Headquarters Map File, I-42.

[13] Inventory of the chattel property of George Rivers at his residence on James Island, dated 3 April 1786, SCDAH, Inventories and Appraisement Book, 1783–1787, pages 426–27.

[14] For more information about enslaved South Carolinians fleeing to the British during the American Revolution, see Ruth Holmes Whitehead, Black Loyalists: Southern Settlers of Nova Scotia’s First Free Black Communities (Halifax, Nova Scotia: Nimbus, 2013).

[15] [Charleston] Columbian Herald, 7 January 1785; State Gazette of South Carolina, 23 March 1786.

[16] SCDAH, Inventories and Appraisement Book, 1783–1787, pages 426–27. Walley, described as a “negro boy” in the 1786 inventory, ran away in January 1805, at which time he was described as being “about 25 years of age.” James Stanyarn[e] advertised for his return in [Charleston] City Gazette, 2 April 1805.

[17] Charleston Morning Post, 2 December 1786.

[18] The Stanyarne marriage announcement appears in [Charleston] City Gazette, 1 January 1795. Under the doctrine of coverture, Eliza’s husband assumed legal control of her property.

[19] See Richard Dwight Porcher and Sarah Fick, The Story of Sea Island Cotton (Layton, Utah: Wyrick & Company, 2005).

[20] James Stanyarne and Elizabeth Mary, his wife, to Robert J. Turnbull, release and plat for $5,000, 28 September 1810, RoD A8: 424–26. The 1777 plat annexed to this conveyance (mentioned above) shows three tracts containing 240, 49, and 42 acres of high ground respectively (a total of 331 acres), but this land is here described as containing 341 acres. See also James T. W. Holmes to Robert J. Turnbull, conveyance, 5 April 1816, RoD Q8: 83–84; George Rivers, executor of the estate of Mallory Rivers, to Robert James Turnbull, conveyance and mortgage, 1 (or 4) February 1821, RoD G9: 307–9.

[21] Ancestry.com, 1850 U.S. Federal Census - Slave Schedules [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2004, accessed on 13 November 2019 through the website of the Charleston County Public Library.

[22] Ancestry.com. U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850-1880 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010, accessed on 13 November 2019 through the website of CCPL.

[23] See Henry F. Bailey to Paul C. Grimball, conveyance of 160 acres, 22 November 1851, RoD O12: 489. Paul C. Grimball transferred his James Island property to his son, Thomas H. Grimball, sometime between 1850 and 1860, but that conveyance was not recorded in a formal manner at the Charleston County Register of Deeds Office. It must have been a sort of early inheritance.

[24] Ancestry.com, 1860 U.S. Federal Census - Slave Schedules [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2004; Ancestry.com. U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850-1880 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010, accessed on 13 November 2019 through the website of CCPL.

[25] Charleston Courier, 30 May 1862.

[26] For contemporary reports about this activity, see Charleston Mercury, issues of 11 and 18 June 1862; Charleston Courier, issues of 4 July, 26 July, 19 August, and 22 September 1862.

[27] I did not find an inventory of the estate of Thomas H. Grimball, probably because of the confused state of affairs in South Carolina in late 1864 and early 1865.

[28] Douglas W. Bostick, A Brief History of James Island: Jewel of the Sea Islands (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2008), 83–89, describes the process by which prior owners of James Island plantations petitioned Federal authorities for restoration, and states that this business was concluded for all James Island plantations between March 1866 and January 1868. In an obituary for Henry B. Grimball, printed in Charleston News and Courier, 4 January 1943, however, a writer asserts that Henry reclaimed this plantation when he was eighteen years of age (that is, in 1878), “through the good graces of [Governor] Wade Hampton.” I have not found a definite solution to this discrepancy.

[29] The Federal census of 1870 places Sarah and Henry Grimball in the household of Sarah’s mother, Martha Bailey, in Charleston’s Ward No. 4. I did not find either of them named in the 1870 agricultural census of James Island, which includes the names of dozens of freemen farming small rented tracts of former plantation lands.

[30] Ancestry.com. U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850-1880 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010, accessed on 14 November 2019 through the website of CCPL

[31] For the marriage announcement, see Charleston News and Courier, 5 March 1885, page 8; for the plat, see Charleston County Register of Deeds, John McCrady Plat Collection, plat No. 2483.

[32] See the obituary for Henry B. Grimball in Charleston Evening Post, 3 January 1943, page 2; and Charleston News and Courier, 4 January 1943, page 2.

[33] A description of school bus routes in Charleston Evening Post, 29 July 1931, page 12, mentions a route passing through “the new loop in Grimball Road.”

[34] Charleston County Register of Deeds, Plat Book J, page 89: “Map of tract of land owned by Est: of Sarah E. Grimball James Island Charleston County, S.C. Surv. and Divided May 1953”; Beulah May Grimball Robinson to Charleston County School District No. 3, conveyance of parcel “M” on the north side of Grimball Road containing 6.2 acres (as described in a plat made by W. L. Gaillard on 23 November 1962), 18 January 1963, RoD O78: 142.

PREVIOUS: A Veteran’s Story: Caring for the Family of Sergeant William Jasper

NEXT: The Genesis of the Harleston Neighborhood, 1672-1770

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments