The Heads of the Two Toms in 1745

Processing Request

Processing Request

Has this ever happened to you: There’s a knock at your front door late at night. You open the door to find a messenger with a letter and a soggy burlap bag. You open the letter—it’s news about a series of recent murders. You look inside the bag and find two human heads. What do you do? If you’re the governor of South Carolina, and its January of 1745, you breathe a sigh of relief, and say “Thank you—I’ve been expecting these.” Today we’ll investigate the story of “the heads of the two Toms,” so make yourself comfortable, and don’t forget to tip the delivery boy.

Last week I introduced the story of a brutal crime that took place in mid-July 1744, when a pair of Notchee (Natchez) Indians attacked and murdered five to ten Catawba Indians as they slept after what was supposed to be a merry feast, but which was in reality a murderous trap. Governor James Glen of South Carolina learned of the Indian murders a few days later and quickly intervened in an effort to prevent an escalation of violence that could potentially erupt into a frontier-wide blood bath. He persuaded the Catawba chief to restrain his warriors and to allow Glen time to obtain justice through a more diplomatic channel. The governor then hosted the Notchee king at his home for a week and compelled him to disown the two murderers and to deliver them to the white man’s government. On both fronts, Glen succeeded in convincing the tribal leaders to remain calm, and to let South Carolina’s provincial government play the leading role in resolving this crisis. In reality, however, the government’s role was quite passive. Glen expected the Notchee king and his people to locate, apprehend, and hand over the culprits, at which time the government would simply convey the murderers (or their remains) to the Catawba. Having concluded these negotiations around the beginning of September 1744, the governor returned to his normal administrative duties (with included an ongoing war with our Spanish and French neighbors) and soon forgot about the Indian matter.

In the aftermath of the mass murder in July 1744, most of the small band of Notchee Indians fled from their reservation near Four Holes Swamp, established in 1738, and dispersed southward into the frontier wilderness. By the end of autumn, the majority of the tribe were back in Colleton County, near the headwaters of the Ashepoo River, where they had originally settled a decade earlier when they first arrived in South Carolina. The Notchee might have enjoyed a small sense of security at this site, being more than one hundred and fifty miles south of the Catawba nation, but in fact they had good reason to feel uneasy. Back in August, Governor Glen had convinced the Catawba chief, whom he called the Little Warrior, to muzzle his warriors and give Glen at least three months to apprehend the Notchee murderers. If he couldn’t deliver the culprits in that time frame, Glen said he would step aside and permit the Little Warrior “to use the Notchee as he thought proper.” That three-month truce expired in late November, however, and the two murderers had not yet been found. As winter settled over the Lowcountry at the end of 1744, the Notchee camped in Colleton County maintained a vigilant watch for both their rogue kinsmen and for vengeful Catawba warriors.

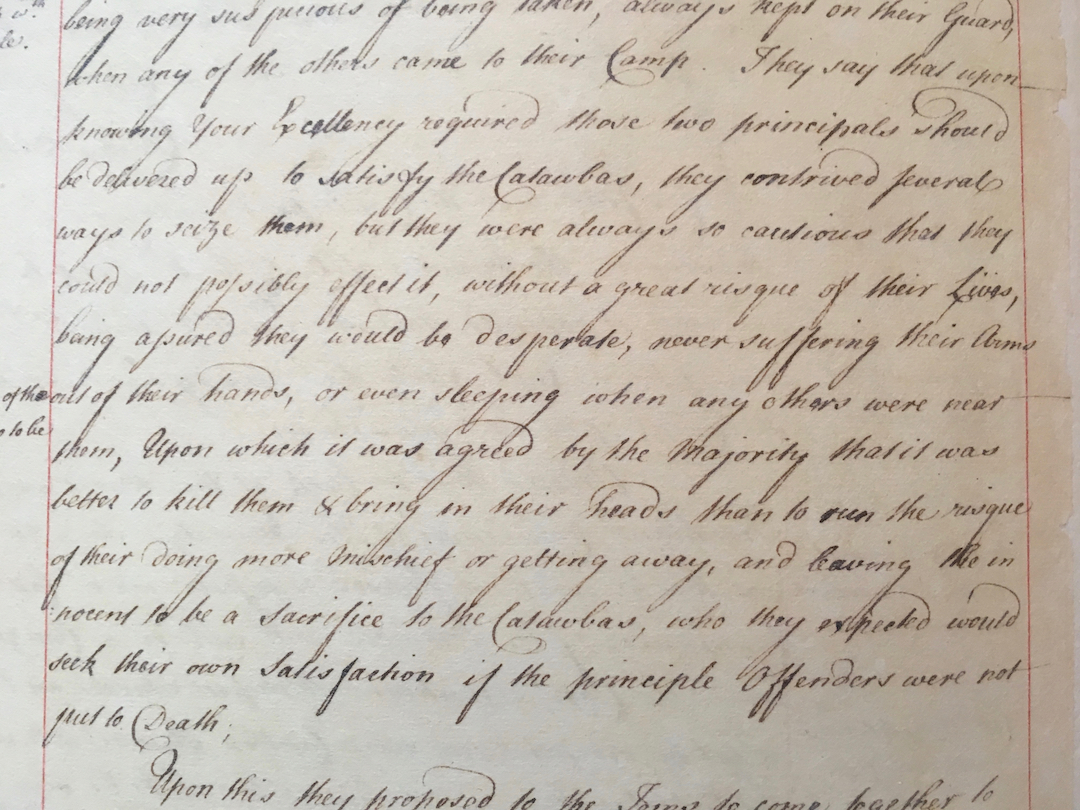

If this story were a made-for-TV movie, right about now the director would cut to a scene in the wilderness where we’d find the two murderers on the run, contemplating their predicament and planning their next move. We the audience would learn details about their motivations, their fears, and their intentions, and the plot would move forward in a traditional manner. But this is a real-life story, and, as a historian, I would much rather find authentic documentary evidence than fabricate details to suit a fictional scenario. Fortunately for us, there is an extant document that helps to fill in the blanks. In late January 1745, the Notchee king told the rest of this story to a white planter in Colleton County, Colonel John Bee, and John Bee related the story in a letter to Governor James Glen. The governor in Charleston read Bee’s letter to his council of advisors, known as His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, and the clerk of that council transcribed Bee’s letter into a manuscript journal that now resides at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia. The story of the Notchee-Catawba murders in the summer of 1744 has been described by a number of historians over the years, but I haven’t found any published sources that mention John Bee’s 1745 letter to the governor.[1] I’ve spent a lot of time in recent years reading through all of the surviving journals of His Majesty’s Council, which are really chock full of interesting details, and I already had this story on my long list of topics to explore further. During a recent trip to the state archive, I photographed the relevant manuscript pages from the 1745 Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina in order to make this podcast.[2]

If this story were a made-for-TV movie, right about now the director would cut to a scene in the wilderness where we’d find the two murderers on the run, contemplating their predicament and planning their next move. We the audience would learn details about their motivations, their fears, and their intentions, and the plot would move forward in a traditional manner. But this is a real-life story, and, as a historian, I would much rather find authentic documentary evidence than fabricate details to suit a fictional scenario. Fortunately for us, there is an extant document that helps to fill in the blanks. In late January 1745, the Notchee king told the rest of this story to a white planter in Colleton County, Colonel John Bee, and John Bee related the story in a letter to Governor James Glen. The governor in Charleston read Bee’s letter to his council of advisors, known as His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, and the clerk of that council transcribed Bee’s letter into a manuscript journal that now resides at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia. The story of the Notchee-Catawba murders in the summer of 1744 has been described by a number of historians over the years, but I haven’t found any published sources that mention John Bee’s 1745 letter to the governor.[1] I’ve spent a lot of time in recent years reading through all of the surviving journals of His Majesty’s Council, which are really chock full of interesting details, and I already had this story on my long list of topics to explore further. During a recent trip to the state archive, I photographed the relevant manuscript pages from the 1745 Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina in order to make this podcast.[2]

Rather than simply read John Bee’s letter to you, I’m going expand the story a bit and include a number of choice quotes from Bee’s telling of the facts he learned directly from his Notchee neighbors in Colleton County. On the 24th of January, 1745, a group of seven Notchee men informed Bee that they had captured the two murderers, whom they called “the two Toms.” Before we continue with their story, let’s pause for a brief diversion into nomenclature. Think back to every Hollywood spaghetti Western you’ve ever seen—films that usually include pretty awful depictions of Native American culture. In those movies, what noun did they use to signify an adult male Indian—the sort who usually galloped around on horseback with a bow and arrows? Hollywood, as well nineteenth-century Romantic literature, told us those young Native men were called “braves,” as in the modern baseball team, the Atlanta Braves, and “warriors” when they were perhaps a bit more experienced. But what did those Native people call themselves? Here in South Carolina in 1745, John Bee told us that the two Notchee murderers were called Toms. Were both men named Thomas? No, we don’t know their given names. Rather, “tom” is apparently the English translation of the Notchee word used to describe an adult male, and perhaps specifically an important adult male. Why “tom”? Because a “tom” is an adult male turkey, as distinct from a juvenile “jake” or a female “hen.” Calling a big man a turkey is an insult in our modern culture, but it seems a fitting description if you’ve ever seen an adult male turkey puff out his chest, fan his majestic tail feathers, and strut proudly to defend his turf. The adult male wild turkey is, in fact, a proud, fierce, and powerful bird that commands respect among both his fellow turkeys and the humans who hunt them. We may never know the proper names of the two Notchee men who murdered several Catawba Indians in July of 1744, but we know that their people called them “the two Toms.”

The seven Notchee leaders who arrived on John Bee’s front porch on the 24th of January, 1745, told him how they captured the two Toms. “Those two fellows” who committed the murders, the Notchee said, “have been away from the rest [of the tribe] since they did that mischief” last July. Where had they been since that time? Instead of retreating southward from the reservation with the rest of the tribe, who were living in fear of Catawba reprisals, the two murderers had moved northward, “endeavouring [sic] to revenge themselves on another of the Catawbas that they had not an opportunity of killing when they committed that murder” last summer. As I mentioned in last week’s episode, we don’t know the motivation behind the murder of five to ten Catawba in July of 1744, and so I think it’s significant that after committing that crime, the Notchee assailants felt their business still was not finished. Whatever jealousy or anger drove them to hunt their supposed enemies, the two Toms found the Catawba nation on high alert, keeping up a vigilant watch for the murderous duo. Being unable to “accomplish their end” of tracking down and killing their human prey, the Toms eventually turned southward to rejoin their families and “to the rest [of the Notchee band], who were encamped above Ashepoo Bridge.” The modern-day bridge over the Ashepoo River in Colleton County is exactly where it has been for the past three centuries, in the path of what we now call Highway 17. If you were driving south on Highway 17 in early 1745, heading from Charleston towards Beaufort, you would have seen the smoke rising from the Notchee campfires to your right as you passed over the Ashepoo River bridge.

The seven Notchee leaders who arrived on John Bee’s front porch on the 24th of January, 1745, told him how they captured the two Toms. “Those two fellows” who committed the murders, the Notchee said, “have been away from the rest [of the tribe] since they did that mischief” last July. Where had they been since that time? Instead of retreating southward from the reservation with the rest of the tribe, who were living in fear of Catawba reprisals, the two murderers had moved northward, “endeavouring [sic] to revenge themselves on another of the Catawbas that they had not an opportunity of killing when they committed that murder” last summer. As I mentioned in last week’s episode, we don’t know the motivation behind the murder of five to ten Catawba in July of 1744, and so I think it’s significant that after committing that crime, the Notchee assailants felt their business still was not finished. Whatever jealousy or anger drove them to hunt their supposed enemies, the two Toms found the Catawba nation on high alert, keeping up a vigilant watch for the murderous duo. Being unable to “accomplish their end” of tracking down and killing their human prey, the Toms eventually turned southward to rejoin their families and “to the rest [of the Notchee band], who were encamped above Ashepoo Bridge.” The modern-day bridge over the Ashepoo River in Colleton County is exactly where it has been for the past three centuries, in the path of what we now call Highway 17. If you were driving south on Highway 17 in early 1745, heading from Charleston towards Beaufort, you would have seen the smoke rising from the Notchee campfires to your right as you passed over the Ashepoo River bridge.

In the second week of January, 1745, “about a fortnight,” before John Bee became involved in this story, the two Toms cautiously appeared on the outskirts of the Notchee camp. Rather than attempting to rejoin the main camp of their fellow tribesmen, the two Toms “sat down at some distance from them, in a camp by themselves, being very suspicious of being taken.” Their extended families no doubt greeted them with expressions mixed with feelings of both love and revulsion, which the exiled warriors reciprocated with guarded salutations. A tenuous channel of communication opened between the two camps, allowing a few members of the tribe to visit the exiles, but the two Toms “always kept on their guard, when any of the others came to their camp.” Through a series of conversations in mid-January, the fugitives learned that several months earlier the Notchee king had made a pact with the white people’s government. Their governor “required” the Notchee to apprehend and “deliver up” the “two principals” who had committed the horrid crimes last July, in order to “satisfy the Catawbas,” and King Will had promised to do “everything in his power” to comply with the governor’s demand. As proud warriors living by an ancient code of honor, the two Toms already knew to be wary of Catawba reprisals for their violent deeds, but now they learned of their king’s plan to betray them to the white man. In the days after their reappearance in Colleton County, the Toms walked a fine line between trying to preserve their kinship with the Notchee and keeping a vigil against potential acts of betrayal.

Meanwhile, back at the main Notchee camp, the tribal leaders debated and “contrived several ways [and methods] to seize them,” but the murderers were “always so cautious” and paranoid that the tribesmen feared for their collective safety. They realized “that they could not possibly effect it [that is, capturing the murderers], without a great risque [sic] of their lives.” Having observed the murderers from a distance for several days, the Notchee people felt “assured” that the two Toms “would be so desperate” as to defend themselves to the last extremity, “never suffering their arms [to be] out of their hands, or even sleeping when any other were near them.” Their king had promised the governor they would deliver the murderers, and the governor had promised the Catawba the matter would be concluded within three months. After five quiet and unproductive months, it might be possible that Catawba warriors were stalking the defenseless Notchee people at that very moment. By attempting to reunite with the tribe, the guilty men were endangering the lives of all the Notchee, and the time for deliberation was running out. Finally, after about two weeks of this uneasy truce between the tribe and the murderous Toms, “the majority” of the Notchee leaders determined “that it was better to kill them [the two Toms] and to bring in their heads [to the governor] than to run the risque [sic] of their doing more mischief, or getting away, and leaving the innocent to be a sacrifice to the Catawbas, who they [the Notchee] expected would seek their own satisfaction if the principle [sic] offenders were not put to death.”

Meanwhile, back at the main Notchee camp, the tribal leaders debated and “contrived several ways [and methods] to seize them,” but the murderers were “always so cautious” and paranoid that the tribesmen feared for their collective safety. They realized “that they could not possibly effect it [that is, capturing the murderers], without a great risque [sic] of their lives.” Having observed the murderers from a distance for several days, the Notchee people felt “assured” that the two Toms “would be so desperate” as to defend themselves to the last extremity, “never suffering their arms [to be] out of their hands, or even sleeping when any other were near them.” Their king had promised the governor they would deliver the murderers, and the governor had promised the Catawba the matter would be concluded within three months. After five quiet and unproductive months, it might be possible that Catawba warriors were stalking the defenseless Notchee people at that very moment. By attempting to reunite with the tribe, the guilty men were endangering the lives of all the Notchee, and the time for deliberation was running out. Finally, after about two weeks of this uneasy truce between the tribe and the murderous Toms, “the majority” of the Notchee leaders determined “that it was better to kill them [the two Toms] and to bring in their heads [to the governor] than to run the risque [sic] of their doing more mischief, or getting away, and leaving the innocent to be a sacrifice to the Catawbas, who they [the Notchee] expected would seek their own satisfaction if the principle [sic] offenders were not put to death.”

Sometime in late January, 1745, the Notchee tribal leaders “proposed to the Toms to come together” as a group and walk up the path to Jacksonboro, a village about seven miles to the east of their camp. The leaders explained that they needed “to buy some things they wanted,” and the only general store in that neighborhood was up the road in Jacksonboro. The two exiled Toms, no doubt suffering under a sleep-deprived state of anxious, lonely paranoia, agreed to walk up the road with seven of their tribesmen. The nine men set out on the morning of January 24th, walking eastward along a sandy narrow road we now call Highway 17. Having crossed over Ashepoo Bridge and walked as far as Benjamin Godin’s plantation on the way to Jacksonboro, the tribal leaders suddenly turned on the Toms and “shot them both down” in the middle of the road—most likely using pistols concealed in their long winter cloaks. Wasting no time to complete their awful business, the Notchee men unsheathed some sort of blade—probably a weapon belonging to one of the Toms—and “beheaded them and bury’d the bodys [sic] by the road.”

Immediately after finishing this gruesome business, the group of seven Notchee men went directly to the nearby house of Colonel John Bee, where they displayed the freshly-severed heads and recounted the entire affair. “Brigadier” John Bee (1707–1749) was a thirty-seven-year-old, well-respected rice planter in Colleton County who was undoubtedly familiar with the Notchee refugees living in the neighborhood. As a local militia captain, Bee had led the first wave of white men to clash with the rebellious slaves who rose up near the Stono River in September 1739. Promoted to colonel of the Colleton County militia, Bee again led his neighbors in the disastrous 1740 expedition launched by S.C. and Georgia against the Spanish at St. Augustine.[3] In short, John Bee was a man familiar with violence and bloodshed, and the Notchee clearly felt comfortable entrusting him with both a confession of their murderous crime and the physical evidence of the bloody deed.

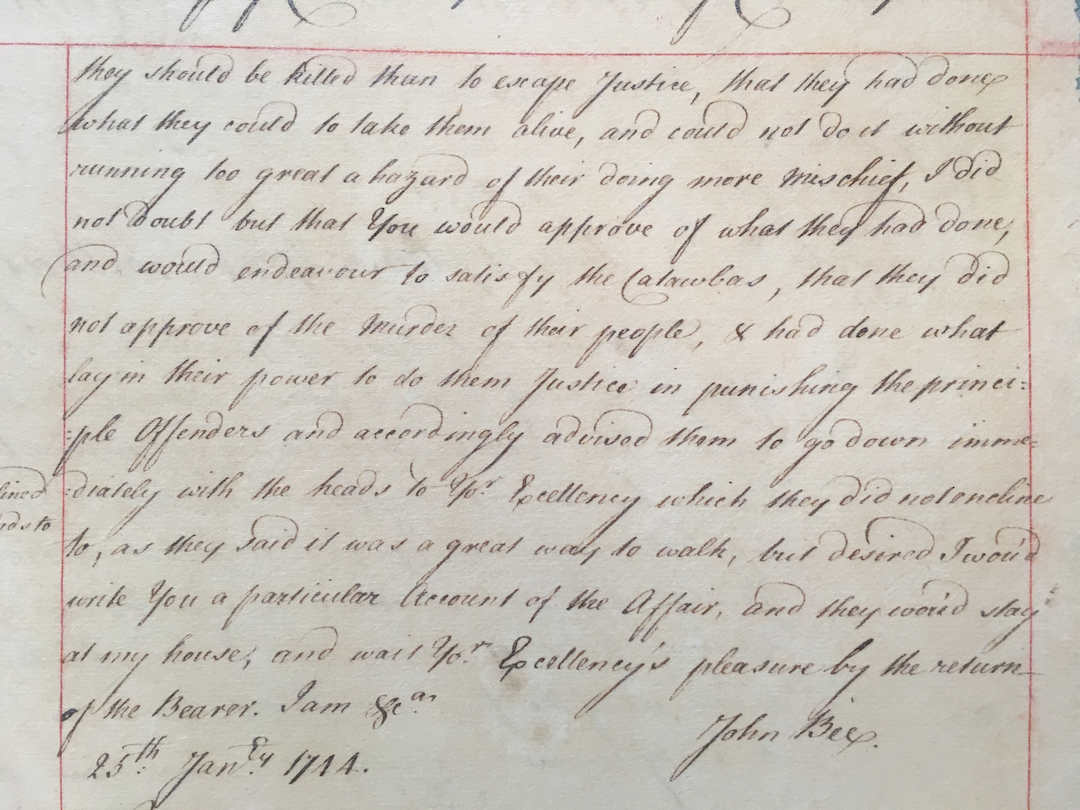

The Notchee men regarded Colonel Bee as one of the principal white men of that neighborhood, and so asked his “opinion of what they had done, and what they should further do in the affair.” Bee told the seven Notchee leaders that he believed Governor Glen “would have been much better pleased had they delivered them [the two Toms] up alive, as also it would be more satisfaction to the Catawbas.” Since that scenario was no longer an option, however, the colonel opined “that it was better they should be killed than to escape justice.” The Notchee men said, “that they did not approve of the murder of their [Catawba] people, & [they] had done what lay in their power to do them [the Catawba] justice in punishing the principle [sic] offenders.” Colonel Bee assured the Notchee that he understood “they had done what they could to take them alive,” and he agreed that such a course of action could not have been accomplished “without running too great a hazard of their [the two Toms] doing more mischief.” In light of the circumstances, said Colonel Bee, the governor would surely “approve of what they had done, and would endeavour [sic] to satisfy the Catawbas.”

The Notchee men regarded Colonel Bee as one of the principal white men of that neighborhood, and so asked his “opinion of what they had done, and what they should further do in the affair.” Bee told the seven Notchee leaders that he believed Governor Glen “would have been much better pleased had they delivered them [the two Toms] up alive, as also it would be more satisfaction to the Catawbas.” Since that scenario was no longer an option, however, the colonel opined “that it was better they should be killed than to escape justice.” The Notchee men said, “that they did not approve of the murder of their [Catawba] people, & [they] had done what lay in their power to do them [the Catawba] justice in punishing the principle [sic] offenders.” Colonel Bee assured the Notchee that he understood “they had done what they could to take them alive,” and he agreed that such a course of action could not have been accomplished “without running too great a hazard of their [the two Toms] doing more mischief.” In light of the circumstances, said Colonel Bee, the governor would surely “approve of what they had done, and would endeavour [sic] to satisfy the Catawbas.”

Colonel Bee then “advised them [the Notchee] to go down immediately with the heads” to Charleston and deliver them personally to Governor Glen. The Notchee men declined making that nearly forty-mile trek, however, because “they said it was a great way to walk.” Instead, they asked Colonel Bee to write a letter providing “a particular account of the affair” and send it along with the severed human heads to the governor. In the meantime, the seven Notchee men told Bee they would stay at his house and await a reply from Governor Glen, either approving or condemning their actions. While it might seem to us that the Notchee invited themselves to stay at Colonel Bee’s House for a few days, in reality they were making a statement about their collective integrity. By remaining at Bee’s house, they acknowledged that, in the eyes of the white man’s law, they had committed a serious crime by executing the two Toms in cold blood. In light of the broader circumstances, however, they felt confident that the law would condone their actions. Whether Governor Glen applauded or condemned the affair, they would stay put and await his decision so that no one could allege that the Notchee had committed murder and fled into the wilderness.

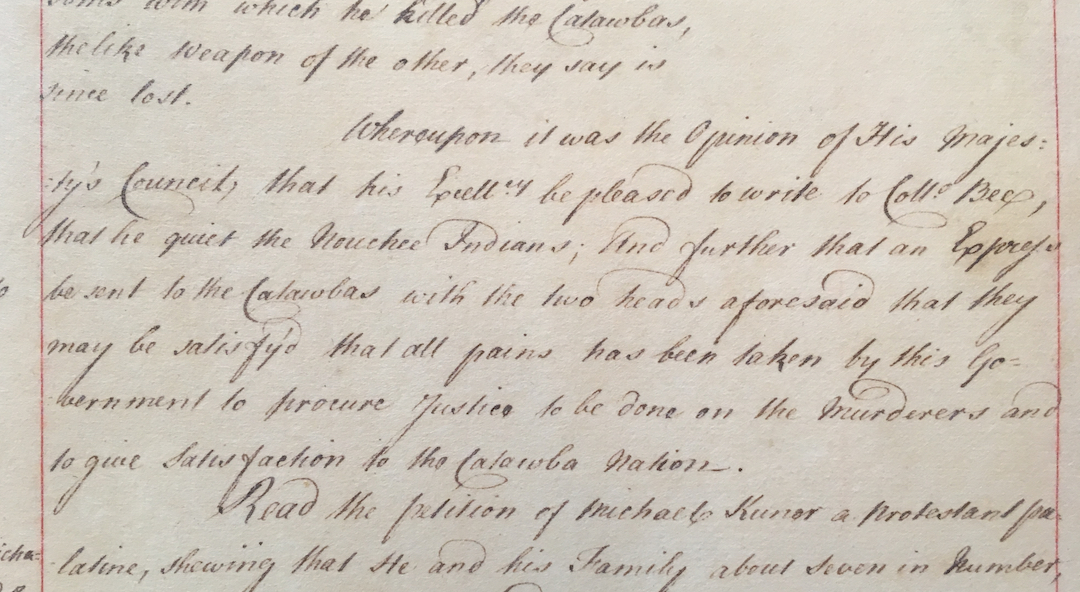

On the morning of January 25th, 1745, John Bee put quill to paper and wrote a letter to Governor James Glen in Charleston. “Last night,” he said, “came seven of the Nouchees [Natchez] to my house with the two heads” of the men wanted for the crimes committed the previous July. Bee summarized the story of how the murderers had tried to rejoin the Notchee camp on the Ashepoo River, and how the tribe had debated which course of action to follow. Although Bee was not personally acquainted with the two wanted men, he told the governor that the Notchee leaders had assured him that the severed human heads they presented to the colonel were indeed “the heads of the two Toms that were principally concerned in the murder of the Catawbas.” In a postscript to his letter, Colonel Bee added that the Notchee men had also delivered to him “the weapon of one of the Toms with which he killed the Catawbas, the like weapon of the other [Tom], they say is since lost.” Having finished his letter, Bee summoned an enslaved boy from his household to fetch a horse and carry the letter, the Tom’s weapon, and a bag containing the two heads to the governor’s house on Charleston Neck.

After riding nearly forty miles from near Jacksonboro to Charleston Neck, a journey of at least three or four hours, the unnamed enslaved boy arrived at the governor’s house later in the afternoon of Friday, January 25th. Governor Glen read the contents of John Bee’s letter that day, but we don’t know his initial reaction, or what he did with the heads at that moment. The enslaved messenger must have stabled his horse and settled in for the night, however, because the governor did not immediately respond to Bee’s letter. Instead, Glen rode into town the next morning for a regularly-scheduled meeting with his cabinet of advisors, collectively known as His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, convened in the Council Chamber in the second story of the Watch House (the present site of the old Exchange building). As the first order of business on Saturday, the 26th of January, the governor shared Colonel Bee’s letter with his attending advisors, including William Bull, James Kinloch, John Cleland, William Middleton, and Richard Hill. The clerk of Council dutifully transcribed all of this business into the journal of that day’s proceedings, but the surviving record doesn’t mention whether or not the governor brought the bag of heads or the Notchee weapon into the Council Chamber for show-and-tell.

After riding nearly forty miles from near Jacksonboro to Charleston Neck, a journey of at least three or four hours, the unnamed enslaved boy arrived at the governor’s house later in the afternoon of Friday, January 25th. Governor Glen read the contents of John Bee’s letter that day, but we don’t know his initial reaction, or what he did with the heads at that moment. The enslaved messenger must have stabled his horse and settled in for the night, however, because the governor did not immediately respond to Bee’s letter. Instead, Glen rode into town the next morning for a regularly-scheduled meeting with his cabinet of advisors, collectively known as His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, convened in the Council Chamber in the second story of the Watch House (the present site of the old Exchange building). As the first order of business on Saturday, the 26th of January, the governor shared Colonel Bee’s letter with his attending advisors, including William Bull, James Kinloch, John Cleland, William Middleton, and Richard Hill. The clerk of Council dutifully transcribed all of this business into the journal of that day’s proceedings, but the surviving record doesn’t mention whether or not the governor brought the bag of heads or the Notchee weapon into the Council Chamber for show-and-tell.

At any rate, we do know that Governor Glen asked his council to consider the affair and to give their best advice on how to proceed. After a brief debate, they advised Glen to write back to Col. Bee immediately with instructions to “quiet the Nouchee [sic] Indians” by condoning their pre-emptive executions and assuring them that the governor would conclude this awful business. The councilors also advised Glen to send an express rider to deliver the two severed heads to the Catawba leaders, “that they may be satisfy’d that all pains has [sic] been taken by this Government to procure justice to be done on the murderers and to give satisfaction to the Catawba Nation.”

That’s where the story ends, at least in the manuscript journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, but we can use our imaginations to wrap up one or two loose ends. At some point later that day, Governor James Glen wrote a letter to John Bee with instructions to assure the Notchee leaders they would not be prosecuted for what we might now call an act of justifiable double homicide. Glen handed his letter to Colonel Bee’s enslaved boy, who galloped back towards Jacksonboro, no doubt relieved to have left the bloody bag of human heads in the governor’s possession. But what happened to the Tom’s weapon, and the two heads? Were they immediately put in the hands of some other poor express rider, who rode more than a hundred miles northward and delivered the smelly, rotting flesh full of maggots and flies to the Catawba chief? Documents on this side of the Atlantic Ocean don’t provide any clues, so we have to look abroad for answers.

Fortunately for us, James Glen recorded a few more words about the conclusion of this episode in a report he sent to the British Board of Trade in December 1751, nearly five years later. In the course of explaining the ups and downs of Indian affairs in recent South Carolina history, Glen proudly mentioned how he had successfully diffused the potential war between the Notchee and the Catawba. He recalled his conversations with the Notchee king during the royal family’s brief residence at the governor’s house in late August 1744, and how King Will had promised to “do everything in his power” to apprehend the two murderous Toms. “Accordingly, a few weeks after,” said Glen (but in truth, five months later), the King of the Notchee “sent me the heads of those two persons in a bagg [sic]. I gave them [the heads] to a surgeon to take out the brains, and put each head in a cask with spirits to preserve them till they got to the Catawbaw [sic] Nation.” So in February of 1745, some poor express rider had to gallop from Charleston to the Catawba nation, near modern-day Rock Hill, South Carolina, carrying two small wooden casks filled with alcohol and human heads.

Fortunately for us, James Glen recorded a few more words about the conclusion of this episode in a report he sent to the British Board of Trade in December 1751, nearly five years later. In the course of explaining the ups and downs of Indian affairs in recent South Carolina history, Glen proudly mentioned how he had successfully diffused the potential war between the Notchee and the Catawba. He recalled his conversations with the Notchee king during the royal family’s brief residence at the governor’s house in late August 1744, and how King Will had promised to “do everything in his power” to apprehend the two murderous Toms. “Accordingly, a few weeks after,” said Glen (but in truth, five months later), the King of the Notchee “sent me the heads of those two persons in a bagg [sic]. I gave them [the heads] to a surgeon to take out the brains, and put each head in a cask with spirits to preserve them till they got to the Catawbaw [sic] Nation.” So in February of 1745, some poor express rider had to gallop from Charleston to the Catawba nation, near modern-day Rock Hill, South Carolina, carrying two small wooden casks filled with alcohol and human heads.

But how would the Catawba survivors of the July 1744 attack recognize the pickled faces of their attackers? Governor Glen provided a ready answer to this question in his 1751 report. “As it is usual amongst the Indians to mark their great men by various figures upon their faces and bodies,” probably meaning tattoos or scarification, Glen explained to his colleagues in London that “the heads [of the two Toms] were immediately known” or recognized by the Catawba people “who had made their escape from their cruelty” in the summer of 1744. The delivery of the two Notchee heads in early 1745 “produced a general joy in the Catawbaw [sic] Nation,” said Glen, “and gave them a very high opinion of us.” In a bold statement congratulating himself for advancing British control over the savage New World, the governor opined that this event represented “perhaps the first instance in America where any tribe of Indians was brought to punish themselves for injurys [sic] done to other Indians, and has in my opinion led the way to all the subsequent submissive behaviour [sic] of the Catawbaws [sic].”[4]

In the weeks and months that followed the conclusion of the Notchee-Catawba affair in the winter of 1745, Governor James Glen was preoccupied with the continuing war with France and Spain and the growing swarm of enemy privateers that plagued the Carolina coastline and crippled the flow of ships through the port of Charleston. These pressing international matters were temporarily set aside that spring, however, when the governor faced another round of urgent native American diplomacy. In late April 1745, nearly a hundred Cherokee men arrived in Charleston, followed immediately by a separate delegation of about two dozen Catawba warriors, who all came to town to hold formal diplomatic talks with Governor Glen.[5] The details of that grand state occasion we’ll save for a future date, but the event provides a fitting conclusion to our story about the two Toms who lost their heads.

James Glen was a stranger to the colonies when he arrived in December 1743 to become governor of South Carolina. Seven months later, he was obliged to summon all his political acumen to diffuse a potentially explosive rift in local Indian affairs. Armed with little experience in such matters, Glen pursued a course of action that, while novel to the Native population, eventually succeeded in restoring peace between two important tribes allied to the British government. Three months after receiving the pickled heads of the two Toms, the king of the Catawba, the Little Warrior, travelled more than a hundred miles to Charleston to thank Governor Glen in person. The two men were strangers who had communicated through intermediaries for many months, but on the 26th of April, 1745, the governor and the Little Warrior shook hands at the Council Chamber and formed a lasting friendship that contributed to the future success of South Carolina.

James Glen was a stranger to the colonies when he arrived in December 1743 to become governor of South Carolina. Seven months later, he was obliged to summon all his political acumen to diffuse a potentially explosive rift in local Indian affairs. Armed with little experience in such matters, Glen pursued a course of action that, while novel to the Native population, eventually succeeded in restoring peace between two important tribes allied to the British government. Three months after receiving the pickled heads of the two Toms, the king of the Catawba, the Little Warrior, travelled more than a hundred miles to Charleston to thank Governor Glen in person. The two men were strangers who had communicated through intermediaries for many months, but on the 26th of April, 1745, the governor and the Little Warrior shook hands at the Council Chamber and formed a lasting friendship that contributed to the future success of South Carolina.

[1] A number of published sources describe the Notchee-Catawba murders of July 1744 and Governor Glen’s actions in August-September of that year. See, for example, Alexander Gregg, History of the Old Cheraws (New York: Richardson & Co, 1867), 10–11; Chapman J. Milling, Red Carolinians (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1940), 228–29, 240; Douglas Summers Brown, The Catawba Indians: The People of the River (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1966), 223; W. Stitt Robinson, ed., Early American Indian Documents: Treaties and laws, 1607–1789, volume 13, North and South Carolina Treaties, 1654–1756 (Frederick, Md.: University Publication of America, 2001), 330–33.

[2] John Bee’s letter to James Glen is found at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), in the manuscript Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, No. 14 (1745), p. 53–55.

[3] Walter Edgard and N. Louise Bailey, eds., Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives, volume 2 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1977), 68–69.

[4] James Glen’s summary of this episode is included in a long report to the Board of Trade, dated December 1751, found among “Records in the British Public Record Office Relating to South Carolina,” volume 24, pp. 409–13.

[5] The arrival of the Indian delegations and their talks with the governor are recorded in SCDAH, Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, No. 14, pp. 176–86 (23–26 April 1745), and the events are summarized in the South-Carolina Gazette, 6 May 1745.

PREVIOUS: Murder at Four Holes Swamp in 1744

NEXT: Under False Colors: The Politics of Gender Expression in Post-Civil War Charleston

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments