The Green Book for Charleston, 1938-1966

Processing Request

Processing Request

The Oscar buzz surrounding the 2018 film, Green Book, has generated a lot of public interest in the publication that inspired the name of the movie. Charleston isn’t part of the film’s 1962 storyline, but our community was definitely included in that eponymous African-American travel guide. Today we’ll investigate the history of the Green Book phenomenon and examine just how accurately mid-twentieth-century Charleston was represented in that long-running publication.

What is the Green Book?

The Green Book was a business directory intended for African-American travelers that was published between 1936 and 1966 by Victor H. Green, a resident of the New York neighborhood of Harlem who worked in New Jersey for the postal service. This serial publication actually had several variant titles, such as The Negro Traveler’s Green Book, The Travelers’ Green Book, The Negro Motorist Green Book, and others, but the shortened title Green Book represents the most common colloquial appellation. It was created to provide information to African-Americans who might be traveling through areas in the United States, especially in the South, where businesses were racially segregated.

The Green Book was a business directory intended for African-American travelers that was published between 1936 and 1966 by Victor H. Green, a resident of the New York neighborhood of Harlem who worked in New Jersey for the postal service. This serial publication actually had several variant titles, such as The Negro Traveler’s Green Book, The Travelers’ Green Book, The Negro Motorist Green Book, and others, but the shortened title Green Book represents the most common colloquial appellation. It was created to provide information to African-Americans who might be traveling through areas in the United States, especially in the South, where businesses were racially segregated.

The Green Book was ostensibly an annual publication (printed in the late spring), but there are several notable gaps in its publication history. No editions of the guide appeared for a period of five years (1942–46) during World War II, and the title pages of the last two known editions, published in the Spring of 1963 and 1966 respectively, indicate that they were intended to cover multiple years (that is, 1963–64, and 1966–67).

Each edition of the Green Book was actually a small paper booklet designed to fit in a coat pocket or in the glove box of an automobile. Like other serial publications containing business listings, such as a telephone book or city directory, each new edition of the Green Book was designed to supersede the previous edition. Most customers disposed of their old, out-of-date Green Book when the new one arrived, and so the little booklets are quite rare today. The most complete collection of surviving editions of the Green Book is found at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a research institution that forms part of the larger New York Public Library. Their staff has scanned every page of the twenty-three volumes in their Green Book collection and created a very useful website that allows you to peruse and even download the digital content: See https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/the-green-book.

The Charleston County Public Library holds three editions of the Green Book (1950, 1953, and 1955), which form part of the historical collections of the John L. Dart Library on King Street. That institution, which opened in 1927 as Dart Hall Library at the corner of Kracke and Bogard Streets, became the principal “Negro branch” of the Charleston Free Library in 1931, and continued to function as a segregated branch until our public library system was integrated in the early 1960s. Two of the three copies of the Green Book held by the old Dart Hall Library, dating from 1950 and 1953, contain circulation cards that indicate library patrons could check-out the books and take them home for review. The present circulation cards are blank, however, so it’s impossible to tell if they never circulated or if the older, filled-up circulation cards were replaced by fresh blank ones. There’s nothing unique about CCPL’s three copies of the Green Book, so I recommend you peruse the online versions rather than ask to handle these fragile documents. You can even print your own Green Book reproduction from the high-resolution scans provided by the New York Public Library.

What does the Green Book contain?

An editorial note from the 1949 edition of the Green Book states that its purpose was “to give the Negro traveler information that will keep from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trips more enjoyable.” Those “difficulties” and “embarrassments” were, of course, the result of legally-sanctioned policies of racial segregation in the Southern states, enacted by a number of so-called “Jim Crow” laws that were designed to ensure white supremacy in areas where Americans of African descent formed a significant percentage or even majority part of the population. In short, the primary purpose of the Green Book was to help travelers of African descent navigate across their country with a minimum of stress related to the potential of racial confrontation, be it mild and humiliating or extreme and violent.

Like most serial publications, the Green Book sold advertising space to offset part of its production costs. In addition to the ubiquitous advertisements, the travel guide also included hundreds of classified listings representing a variety of businesses, such as filling stations, pharmacies, beauty parlors, barber shops, taverns, hotels, and restaurants. The proprietors of these businesses did not pay a fee to the Green Book publisher for this privilege; rather, the publisher relied on word-of-mouth recommendations from travelers to compile his business guide.

The 1949 edition of the Green Book (page 1) includes an editorial note that provides a useful explanation of its listing practices, which I’ll reproduce in its entirety: “There are thousands of first class business places that we don’t know about and can’t list, which would be glad to serve the traveler, but it is hard to secure listings of these places since we can’t secure enough agents to send us the information. Each year before we go to press the new information is included in the new edition. When you are traveling please mention the Green Book, in order that they [that is, business proprietors] might know how you found their place of business, as they can see that you are strangers. If they haven’t heard about this guide, ask them to get in touch with us so that we might list their place.”

The 1936 prototype edition of the Green Book apparently contained listings only for business within the orbit of New York City, but no copies of that first edition can now be found. The 1937 edition, which consists entirely of advertisements for businesses in New York and New Jersey, contains a note from the publisher identifying it as his “premier issue.” The 1938 edition contains advertisements as well as a classified list of business, arranged alphabetically by state and then by city within each state, but the coverage only includes states east of the Mississippi River. All of the subsequent editions of the Green Book, from 1939 to 1966, include advertisements and listings from nearly every U.S. state, but businesses in the New York metropolitan area always formed the bulk of its content. Furthermore, it’s important to note that the communities listed in the Green Book include cities and towns, big and small, but not suburbs or rural farming areas.

The 1936 prototype edition of the Green Book apparently contained listings only for business within the orbit of New York City, but no copies of that first edition can now be found. The 1937 edition, which consists entirely of advertisements for businesses in New York and New Jersey, contains a note from the publisher identifying it as his “premier issue.” The 1938 edition contains advertisements as well as a classified list of business, arranged alphabetically by state and then by city within each state, but the coverage only includes states east of the Mississippi River. All of the subsequent editions of the Green Book, from 1939 to 1966, include advertisements and listings from nearly every U.S. state, but businesses in the New York metropolitan area always formed the bulk of its content. Furthermore, it’s important to note that the communities listed in the Green Book include cities and towns, big and small, but not suburbs or rural farming areas.

How is Charleston represented in the Green Book?

The “Charleston” listings in the Green Book represent specifically and solely the peninsular City of Charleston, not Charleston County in general. In the twenty-one surviving editions of the Green Book published between 1938 and 1966, there are a total of ninety-seven listings for Charleston, averaging about four listings per year.[1] Looking closely at those ninety-seven listings, we can identify four that represent two businesses that are not actually located in Charleston, but were listed under our city by mistake.[2] The remaining ninety-three listings, spread over a period of nearly three decades, represent just twelve distinct Charleston businesses, the details for which are repeated in multiple editions. These twelve Charleston business listings include five “tourist homes” (Alston, Gladsden, Harleston, Mayes, and Serrant), five restaurants (Brooks Grill, Green Grill, Harleston’s Grill, Queen’s Tea Room, and Scott’s Restaurant), one hotel (the James Hotel), and one taxi service (First Class Taxi).

In recent weeks, I’ve shared these summary statistics with a few friends and colleagues, and I was struck by the consistency of their respective reactions. Several people expressed a sigh of disappointment when they heard that the various editions of the Green Book contain so few listings for Charleston. Some were shocked, but then lamented that the low numbers were surely a predicable sign of the systemic discrimination once rampant in Charleston. No matter how you slice it, three or four listings per year is a very small number of businesses serving the city’s large African-American community, which once formed the majority of the city’s population. So we, the scrupulous readers, have to ask—does the Green Book provide an accurate representation of mid-twentieth-century Charleston’s black community?

Are the Charleston listings in the Green Book comprehensive?

The short answer is an emphatic NO! The small number of local business listings in the various editions of the Green Book does not represent an accurate or comprehensive snapshot of African-American business life in mid-twentieth-century Charleston. The long answer is a bit more complicated.

The short answer is an emphatic NO! The small number of local business listings in the various editions of the Green Book does not represent an accurate or comprehensive snapshot of African-American business life in mid-twentieth-century Charleston. The long answer is a bit more complicated.

If you browse through the pages of any edition of the Green Book published between 1938 and 1966, you’ll find business listings for several cities and towns across South Carolina. If you look carefully at these listings, however, you’ll notice a curious geographical phenomenon. I haven’t made a systematic statistical comparison of all the Green Book listings for South Carolina, but I noticed that there seem to be more listings for Upstate communities, such as Greenville, Spartanburg, and Cheraw, where the black population was relatively small, than there are for Lowcountry communities such as Charleston, Georgetown, and Beaufort (misspelled “Beauford” in every edition), where African Americans historically formed a much larger percentage of the total population.

In other words, there seems to be an inverse relationship between the number of Green Book listings for a given community in South Carolina and the racial demographics of the community in question. In places with a relatively small black population, it seemed more important to provide information for travelers, whereas the need for robust travel information was apparently less important in communities with significantly larger black populations. This hypothetical calculus is not stated in any edition of the Green Book, of course, and is based solely on my perusal of the extant editions available online. Within the city of Charleston, however, I’ve made a more comprehensive study of the Green Book listings and compiled some specifics that help to prove my point. Along with today’s podcast I’m posting a spreadsheet containing a chronological summary of all of the Charleston listings in the surviving editions of the Green Book, 1938-1966, so you can peruse the raw data for yourself.[3]

Between 1930 and 1970, which is roughly the time frame of the Green Book’s existence, the population of the City of Charleston actually declined, from a total of 71,275 in 1930 to 66,945 in 1970. While many white Charlestonians moved the new suburbs off the peninsula after World War II, the African-American population of the City of Charleston remained remarkably stable, hovering just above 30,000 people, or roughly 45% of the total urban population, between 1930 and 1970. In other words, if you were a traveler driving into urban Charleston around the middle of the twentieth century, and you stopped to ask a random citizen for directions, there was a 45% chance that the citizen would be black. With a minimum amount of effort and discretion, therefore, an African-American tourist could easily avoid “running into difficulties [and] embarrassments” in Charleston without the aid of the Green Book. In short, I suspect that out-of-town black visitors to mid-twentieth-century Charleston relied less on the Green Book than similar travelers visiting such places as Columbia, Spartanburg, or Cheraw, not to mention such places as Peoria or Albuquerque that had much smaller black populations.

No edition of the Green Book included a comprehensive listing of every African-American business in Charleston or any other city represented in that annual publication. Such a task was beyond the scope of Mr. Green’s staff, and beyond the purpose of his publication. Furthermore, because the Green Book staff relied on information supplied voluntarily by travelers, these annual publications contain a fair number of misspelled names and inaccurate street address. The task of compiling a complete list of black businesses in mid-twentieth century Charleston is well beyond the scope of this podcast, as is the task of documenting all the errors that appear in the various Green Book editions. To prove these points, however, I’ll mention a few sample entries to illustrate the larger picture.

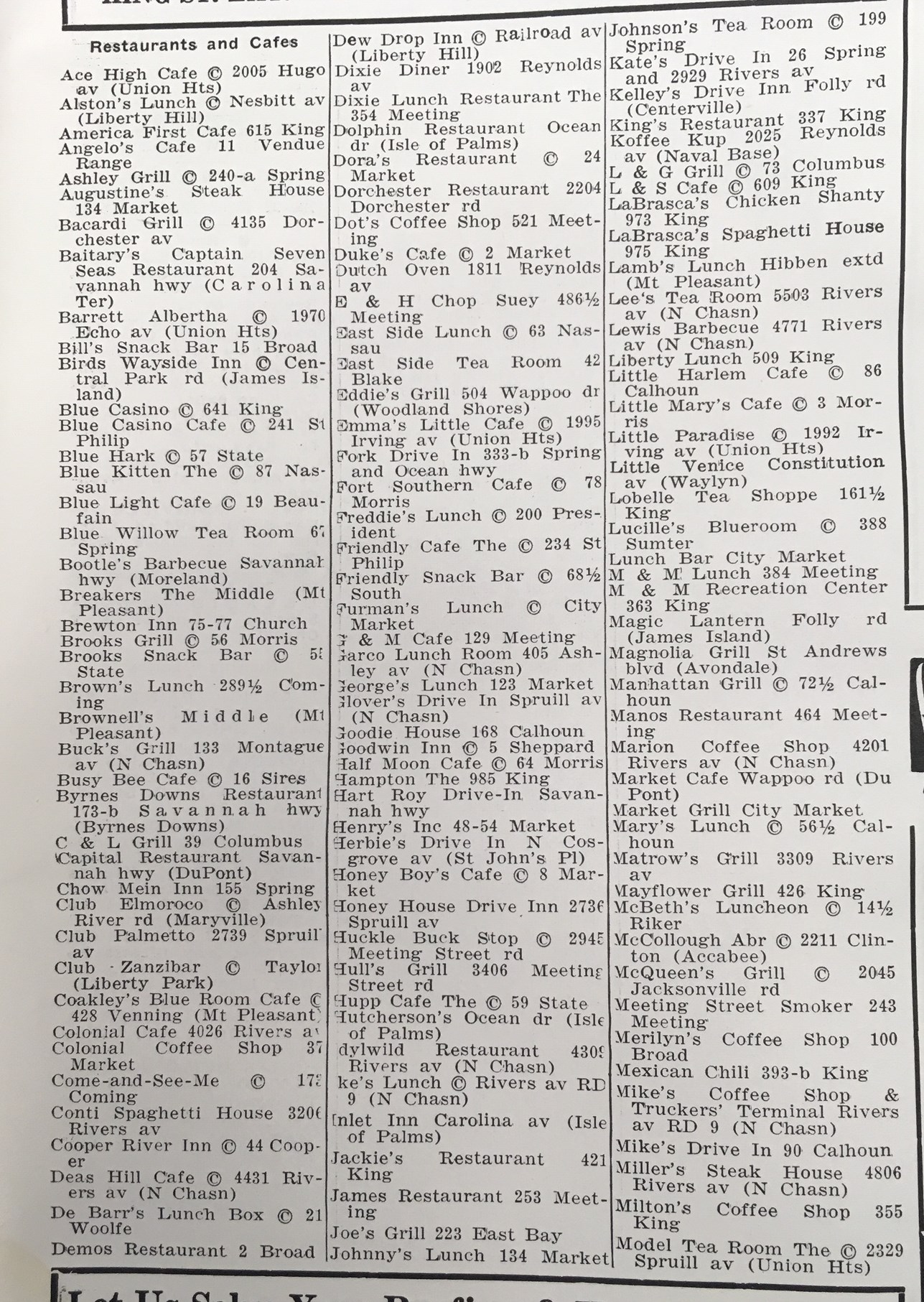

The Green Book for 1950, for example, includes no listings for restaurants in Charleston, but there is a single entry for a “tavern” (actually Mrs. Harleston’s “tourist home” with a liquor license). To see if this dearth of restaurants in the Green Book accurately reflected the culinary reality of Charleston in 1950, I went straight to the large collection of City Directories held in the South Carolina History Room here at CCPL. In the 1950 classified listing of Charleston businesses, I found no classification for “tavern,” so I looked under “restaurant” instead. There I found two solid pages of restaurants listed in alphabetical order. Those serving African-American, or “colored” patrons, included a small letter “c” in a circle (©), like the symbol for copyright, next to the name. While the majority of the listings in 1950 were for white-only restaurants, there were more than seventy “colored” restaurants in the Charleston metro area at that time (see the images on this page). Not a single one of those seventy-odd restaurants is mentioned in the Green Book.

The Green Book for 1950, for example, includes no listings for restaurants in Charleston, but there is a single entry for a “tavern” (actually Mrs. Harleston’s “tourist home” with a liquor license). To see if this dearth of restaurants in the Green Book accurately reflected the culinary reality of Charleston in 1950, I went straight to the large collection of City Directories held in the South Carolina History Room here at CCPL. In the 1950 classified listing of Charleston businesses, I found no classification for “tavern,” so I looked under “restaurant” instead. There I found two solid pages of restaurants listed in alphabetical order. Those serving African-American, or “colored” patrons, included a small letter “c” in a circle (©), like the symbol for copyright, next to the name. While the majority of the listings in 1950 were for white-only restaurants, there were more than seventy “colored” restaurants in the Charleston metro area at that time (see the images on this page). Not a single one of those seventy-odd restaurants is mentioned in the Green Book.

Every surviving edition of the Green Book, from 1938 through 1966, includes a listing for Mrs. Gladsden’s “tourist home” at No. 15 Nassau Street. Her real name was Anna Eliza Gadsden, however, and she died in 1937, before the Green Book even began including Charleston. If you were a traveler arriving “from off,” and knocked at the door of 15 Nassau Street, you’d find Mrs. Gadsden’s daughter, Mrs. Jessie Jones, who maintained the short-term-rental business that her mother had started decades earlier.

Similarly, every surviving edition of the Green Book includes a listing for a “tourist home” operated by one Mrs. Mayes. That women, Annie C. Mayes, died in 1944, however, and her son, Preston Robinson, continued to operate her boarding house for several more decades.

The “tourist home” run by one Mrs. Alston is included in four editions of the Green Book, from 1938 through 1941. The book gives her address as No. 43 South Street, but the city directories of that era place Mrs. Elizabeth Alston at No. 53 South Street. Similarly, a restaurant called the “Green Grill” is included in the the Green Book of 1939, 1940, and 1941 at No. 186 Spring Street, but according to contemporary city directories, that business was actually located at No. 11 Queen Street.

A restaurant called Brooks’s Grill at No. 58 Morris Street is listed in just three editions of the Green Book (1959, 1960, 1961). That business, owned by Mr. Albert Brooks, was actually at No. 56 Morris Street (at the northeast corner of Morris and Felix Streets), and it operated for more than thirty years, between 1945 and the late 1970s. And the more famous Brooks Motel, which opened across the street in 1963 and hosted such dignitaries as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., isn’t even mentioned in the Green Book.[4]

The only Charleston business to purchase advertising space in the Green Book was the James Hotel, which paid for a small illustrated advert to mark its opening in 1952. Located at No. 238 Spring Street, the James Hotel was listed in multiple editions of the Green Book through the end of that publication. Billing itself as Charleston’s only “full-service” hotel for the black community, with a swanky ballroom and adjoining restaurant, the James Hotel declined in the years after desegregation and finally closed in 1978. Built of brick and glass in the mid-century modernist style, the once-vibrant James Hotel was demolished in the 1980s to make way for the present McDonald’s fast-food restaurant, now located at the northwest corner of Spring and Norman Streets.[5]

The Legacy of the Green Book:

In summary, we can state with certainty that the Green Book listing of black-friendly business in mid-twentieth-century Charleston is incomplete, and the names and addresses provided therein are sometimes inaccurate. Between 1938 and 1966—the years in which Charleston appears in the various editions of the Green Book—there were many dozens of black-owned business in Charleston, as well as many white-owned business that accommodated African-American customers in some fashion. Charleston’s small footprint within the pages of the Green Book represents just a miniscule snapshot of a much larger and much more vibrant social and economic presence on the streets of the Palmetto City.

In defense of Mr. Victor Green and his staff, it’s important to note that every edition of the Green Book contained a legal disclaimer from the publisher: The business listings contained in the Green Book were as complete and as accurate as the information that had been given to them from third parties. The publisher could not be held liable for inaccurate or faulty information, nor did inclusion in the Green Book denote any sort of recommendation from the publisher. Looking back at its legacy from the distance of more than half a century, we can’t expect the Green Book to function as a sort of magic decoder ring for mid-twentieth-century black America. It was an imperfect, for-profit business venture based in New York City that sought to help traveling customers find businesses in a variety of far-flung destinations across the expansive landscape of North America.

It’s also important to note that from the beginning of the Green Book, its publisher envisioned the future obsolescence of this travel guide. Every edition of the Green Book contains some expression of this idea, but the 1949 edition includes a rather eloquent statement worth quoting in full: “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment. But until that time comes we shall continue to publish this information for your convenience each year.”

True to Mr. Green’s prediction, the Green Book ceased publication after 1966, in the wake of the Civil Rights Act passed by the U.S. Congress in 1964. That Federal law, which battled stiff resistance from white Southern conservatives before winning ratification in July 1964, prohibited proprietors of public accommodations to discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Although that long-overdue Federal law went into effect immediately after its ratification, the enforcement of its anti-discrimination provisions varied from state to state across the union.

Anecdotal evidence here in Charleston (newspaper interviews and retrospective conversations) suggests that most white business in this city, specifically hotels and restaurants, grudgingly but dutifully complied with the new law right away. Despite this change, customers both black and white generally continued to patronize businesses within their habitual sphere of comfort. De facto segregation prevailed in Charleston, well beyond the Civil Rights Act of 1964, among neighborhood businesses that catered to a relatively small, local clientele. Most of this area’s larger businesses, especially those catering to out-of-town visitors, however, made a much faster and more discernible effort to accommodate the needs of their increasingly diverse customers.

In recent years, Charleston has become one of the top tourist destinations in the world, with nearly six million visitors each year coming here to dine, shop, tour, and sleep. All of this activity pumps many millions of dollars into the local economy and employs tens of thousands of local residents. Reflecting back on the history of the Green Book helps us to remember that segregation was not just morally wrong—it was also a financially backward policy. Charleston is a wonderful place to live and work, but it’s not a perfect place—yet. As long as we keep learning from the mistakes of the past, however, I’m confident that we’ll continue to improve.

If you’d like to explore the Green Book online, you can visit the digitized collection of twenty-three editions curated by the New York Public Library. That institution has also created a virtual map of businesses across the United States that are listed in the Green Book. Closer to home, the University of South Carolina has also created their own robust map of 1956 Green Book listings across the nation.

If you’d like to learn more about African-American business in mid-twentieth-century Charleston, or any other aspect of African-American history within Charleston County, you’re welcome to visit or to contact the South Carolina History Room, located within the Charleston County Public Library’s main branch at 68 Calhoun Street. But be careful—learning about our community’s colorful past can be habit-forming!

[1] 1937: 0 listings for Charleston; 1938: 4 listings; 1939: 8 listings; 1940: 7 listings; 1941: 9 listings, 1947: 6 listings; 1948: 6 listings, 1949: 5 listings, 1950: 5 listings, 1951: 3 listings; 1952: 4 listings; 1953: 2 listings; 1954: 2 listings; 1955: 3 listings; 1956: 3 listings; 1957: 3 listings; 1959: 6 listings; 1960: 6 listings; 1961: 6 listings; 1962: 3 listings; 1963–64: 3 listings; 1966–67: 3 listings.

[2] A few editions of the Green Books also included two business under Charleston that are actually located in other cities: the Waverly Hotel in Columbia (1948, 1949, 1950), and City Taxi of Anderson Street, unknown location, listed under Charleston in 1939.

[3] College of Charleston student intern Abigail Calvert assembled the spreadsheet of Charleston listings in the Green Book, 1938–1966, and compared that data with contemporary city directories. Her careful work greatly facilitated my ability to extract summary statistics mentioned in the preceding paragraphs.

[4] A brief biographical sketch of Albert Brooks appears in the Charleston Evening Post, 25 January 1967, page 1B. A story about the opening of the Brooks Hotel, at the northwest corner of Morris and Felix Streets, appears in Charleston News and Courier, 3 May 1963, page 8B.

[5] Charleston Evening Post, 14 February 1989, “Business Review,” page 4: “James Hotel a Part of Area Black History.”

PREVIOUS: Abraham the Unstoppable, Part 2

NEXT: Abraham the Unstoppable, Part 3

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments