Granville Bastion and the Unfinished Fort of 1697

Processing Request

Processing Request

After the South Carolina General Assembly resolved in the spring of 1696 to build a brick fortification in Charleston at the east end of Broad Street, a series of revisions enacted during the following year altered both its location and its design. The project was moved to a familiar beachfront, still visible today, and expanded into the shape of a formidable, modular structure. Although this imposing design was never completed, terse government documents, combined with drawings held in distant archives and surviving brickwork, provide sufficient clues to reimagine the forgotten Charleston fortress of 1697.

Today’s program is about the beginning of Charleston’s first permanent fortification project, a brick structure commenced in 1697 and later called Granville Bastion. A bastion, for those not familiar with the term, is a diamond-shaped structure that projects outward from the corner of a larger, polygonal fortification. Anyone acquainted with the early maps of urban Charleston, especially the so-called “Crisp Map” of 1711 and the two maps published by Bishop Roberts in 1739 (the “Ichnography of Charles Town” and “An Exact Prospect of Charles Town”) will recognize Granville Bastion as the southeastern corner of a line of fortifications that surrounded approximately sixty-two acres of the early town. Readers of early South Carolina history will recognize Granville Bastion as the site of the colony’s first gunpowder magazine and the official site for the ceremonial proclamation of successive royal governors and successive declarations of war. Fans of historic preservation will recall that the substantial brick remnants of Granville Bastion support the foundations of the Missroon House at 40 East Bay Street, the headquarters of the Historic Charleston Foundation.

Granville Bastion, in short, is one of the best-remembered features and most intact remnants of the myriad fortifications that were built across Charleston’s urban landscape during the city’s first century. Copious information survives to illuminate the later years of this bastion’s history, but I have to admit that I’ve been struggling for years to interpret the documentary evidence relating to the initial stages of its construction in the late 1690s. The fortifications of early Charleston were built by the provincial government, and the extant government records from the turn of the eighteenth century contain only very sparse and somewhat confusing descriptions of that work. After reviewing the evidence countless times, I’ve reached a conclusion that I think will surprise many people: Granville Bastion began as the southeastern corner of a four-bastioned fort that was never completed.

Granville Bastion, in short, is one of the best-remembered features and most intact remnants of the myriad fortifications that were built across Charleston’s urban landscape during the city’s first century. Copious information survives to illuminate the later years of this bastion’s history, but I have to admit that I’ve been struggling for years to interpret the documentary evidence relating to the initial stages of its construction in the late 1690s. The fortifications of early Charleston were built by the provincial government, and the extant government records from the turn of the eighteenth century contain only very sparse and somewhat confusing descriptions of that work. After reviewing the evidence countless times, I’ve reached a conclusion that I think will surprise many people: Granville Bastion began as the southeastern corner of a four-bastioned fort that was never completed.

Those of us who are familiar with the urban landscape of colonial-era Charleston tend to take for granted the system of bastions, entrenchments, and redans that formed a trapezoid of fortifications around sixty-two acres of the town in the first quarter of the eighteenth century. Many people regard this defensive phenomenon as the result of a unified construction campaign, as if the plan to surround the town commenced with the settlement of Charleston. In reality, however, the town’s earliest fortifications grew slowly and organically, without a grand master plan. When work commenced in 1697 to build the first permanent fortifications in Charleston, the brick structure that became known as Granville Bastion was not intended as the southeastern corner of a large, fortified trapezoid surrounding a major portion of the town, but rather as the southeastern corner of a much smaller, two-acre fort. Like similar enclosed forts built at New Amsterdam (later New York), St. Augustine, and Nassau, among other places, this unnamed four-bastioned fort was designed to stand adjacent to, but separate from, the civic heart of urban Charleston.

The documentary evidence supporting this conclusion is couched within the larger story of England’s nine-year war with France known in Europe as the War of the Grand Alliance and in America as King William’s War (1689–1697). Charles Town (renamed Charleston in 1783), the capital and sole port of the southern part of the Carolina Colony, was the southernmost English outpost on the mainland of North America. The early settlers had fortified the town in the 1680s with some rudimentary fortifications built of earth and wood along the Cooper River waterfront. Back in England during the early 1690s, the Lords Proprietors who owned the Carolina Colony implored the provincial government in Charleston to construct more permanent fortifications, but factional divisions within the local Assembly stunted progress towards that objective. Furthermore, the English colonists here felt less anxious about the threat of a French attack. Carolina was then at peace with her Spanish neighbors in Florida, and the nearest French outpost was a thousand miles away in the Caribbean.

The documentary evidence supporting this conclusion is couched within the larger story of England’s nine-year war with France known in Europe as the War of the Grand Alliance and in America as King William’s War (1689–1697). Charles Town (renamed Charleston in 1783), the capital and sole port of the southern part of the Carolina Colony, was the southernmost English outpost on the mainland of North America. The early settlers had fortified the town in the 1680s with some rudimentary fortifications built of earth and wood along the Cooper River waterfront. Back in England during the early 1690s, the Lords Proprietors who owned the Carolina Colony implored the provincial government in Charleston to construct more permanent fortifications, but factional divisions within the local Assembly stunted progress towards that objective. Furthermore, the English colonists here felt less anxious about the threat of a French attack. Carolina was then at peace with her Spanish neighbors in Florida, and the nearest French outpost was a thousand miles away in the Caribbean.

To overcome the political logjam in Charleston, the Lords Proprietors sent one of their own members, John Archdale (1642–1717), to take charge of the provincial government temporarily. Governor Archdale arrived here in the autumn of 1695 with a specific mission to convince the South Carolina legislature to fund the construction of permanent fortifications for the capital town. As I described in detail in Episode No. 181, the Assembly ratified an act in March of 1696 to build “a ffortress battery or ffortification at the east end of the Broad Streete.” That act did not articulate any design specifics; rather, it appointed a body of commissioners who were to design the fortification and oversee its construction. No work was accomplished during the summer of 1696 as tax revenue began to accrue to the project, and Governor Archdale prepared to return to England. Having accomplished his objectives, Archdale commissioned his nephew, Joseph Blake (1663–1700), to act as deputy governor, and sailed home in late October.

South Carolina’s bicameral General Assembly reconvened in Charleston the 24th of November, 1696, and the following day Governor Blake delivered a speech outlining his objectives for the current legislative session. Among the items requiring attention, Blake recommended that the lower or Commons House of Assembly should set in motion the project authorized during the previous session eight months earlier, and “that some emediate care be taken for fortifieing.” In response, the Commons House appointed a committee of four members to meet with a committee of the Upper House of Assembly to discuss the implementation of the fortification act of March 1696.

At this point, some unknown members of the legislature questioned the wisdom of building a large fortification at the east end of Broad Street. Such a structure, placed in the center of Charleston’s commercial waterfront and at the intersection of the town’s principal thoroughfares, would impede the flow of commerce and likely form a nuisance to future inhabitants as the town matured. To address these concerns, the members of the Commons House instructed their newly-formed committee “to survey and consider whether there be not a more convenient place or places ffor ffortifieing in Charles Towne then the place appoynted by Act of Assembly,” and to report back to their colleagues as soon as possible.[1]

At this point, some unknown members of the legislature questioned the wisdom of building a large fortification at the east end of Broad Street. Such a structure, placed in the center of Charleston’s commercial waterfront and at the intersection of the town’s principal thoroughfares, would impede the flow of commerce and likely form a nuisance to future inhabitants as the town matured. To address these concerns, the members of the Commons House instructed their newly-formed committee “to survey and consider whether there be not a more convenient place or places ffor ffortifieing in Charles Towne then the place appoynted by Act of Assembly,” and to report back to their colleagues as soon as possible.[1]

The committees of the two legislative houses met during the evening of November 25th or the following morning and walked along Charleston’s mostly-vacant waterfront to discuss the location of the proposed fortification. On the afternoon of November 26th, the committee presented to the Commons House a brief report of their findings. The majority of the members of the joint committee were of opinion that the site appointed by the act of March 1696—the east end of Broad Street—was not the best location for a new fortification. Instead, the committee recommended that “the poynt of sand to the northward of the creeke commonly called Collins his Creeke, is the most convenient place for fortifieing.”

The “poynt of sand” mentioned in 1696 is the small beach that is still visible on the east side of East Bay Street, slightly north of the east end of Water Street, where the High Battery seawall (built 1809–1818) begins. Water Street was formerly a creek that was known during most of the eighteenth century as Vanderhorst Creek, but during the final years of the seventeenth century it was apparently called Collins’s Creek. The sandy beach to the north of the creek formed part of a small tract of land identified as Lot A in the original town plan called the “Grand Model” of Charleston, which lot and the adjacent marsh had been granted to members of the Colleton family in the spring of 1681.[2] Although this privately-owned site was vacant in 1696, the provincial government was empowered to exercise the right of eminent domain to expropriate real estate for public projects deemed necessary for the safety of the community in general.

The Commons House did not immediately respond to the proposed change of location, but ordered the fortification report to be the topic of debate the following day. In the meantime, the House ordered its committee to return to the “poynt of sand” and “make search whether ffresh watter can be had in the poynt of land aforesaid and report the same to this House to morrow morning.”[3] The following day, November 27th, the committee reported that they had probed the ground at the aforementioned spot but did not find a source of fresh water for a well. Although a supply of fresh water would be necessary within an enclosed fortification during an attack, the members of the Commons House were not deterred by the committee’s negative report. Following a brief, unrecorded debate of the matter, the majority of the House concurred “that the fortification be built upon the poynt of sand aforesaid.”[4]

The Commons House did not immediately respond to the proposed change of location, but ordered the fortification report to be the topic of debate the following day. In the meantime, the House ordered its committee to return to the “poynt of sand” and “make search whether ffresh watter can be had in the poynt of land aforesaid and report the same to this House to morrow morning.”[3] The following day, November 27th, the committee reported that they had probed the ground at the aforementioned spot but did not find a source of fresh water for a well. Although a supply of fresh water would be necessary within an enclosed fortification during an attack, the members of the Commons House were not deterred by the committee’s negative report. Following a brief, unrecorded debate of the matter, the majority of the House concurred “that the fortification be built upon the poynt of sand aforesaid.”[4]

Because the provincial government needed to draft a new law to legitimize the revised location and to justify the expropriation of private property, the Commons House appointed a committee to prepare an “additionall bill for ffortifieing Charles Towne.” This work coincided with the arrival of credible reports that a French fleet was outfitting in the Caribbean to sack the Carolina capital, which induced the Assembly to expand the powers granted to the commissioners of the fortification project. The revised bill, which empowered the commissioners to impress or commandeer whatever laborers and materials they deemed necessary, was read three times by both Houses of the Assembly and amended during the following week.[5]

The preamble to South Carolina’s revised fortification act, ratified on December 5th, 1696, noted that the Assembly had “more deliberately considered that matter” and found “ye point of Sand to ye Northward of ye Creek commonly called Collins his Creek, a more convenient place” for its construction. Accordingly, the legislature ordered that the “fortress battery or ffortification designed to be built at ye aforesd east end of ye broad street called Cooper Street shall now be speedily & effectually built at ye aforesd point of sand to ye northward of ye creek commonly called Collins his Creek or any part thereof as ye commissioners shall think fitt.” The commissioners overseeing the project were further empowered to impress “provisions bricks stone lime timber iron & other materials for ye building & carrying on ye worke of ye sd ffortification, & also to impress or force to work on ye said fortification, so many masons bricklayers carpenters joyners labourers or other artificers” as might be necessary to expedite the work.[6]

The text of the revised fortification act of December 1696, like its predecessor ratified the previous March, did not articulate any details about the design for the proposed “fortress battery or ffortification.” Nevertheless, the text of a latter discussion demonstrates that the commissioners superintending the project soon had a design in hand. That plan does not survive among the archival records of South Carolina’s colonial government, but Governor Blake and his Council of advisors apparently sent at least one copy to the Lords Proprietors along with news of their revised plans. More specifically, I believe their design appears on an undated, rudimentary plat of Charleston that forms part of the John Archdale record book, 1690–1706, which is now held by the Library of Congress.[7]

The text of the revised fortification act of December 1696, like its predecessor ratified the previous March, did not articulate any details about the design for the proposed “fortress battery or ffortification.” Nevertheless, the text of a latter discussion demonstrates that the commissioners superintending the project soon had a design in hand. That plan does not survive among the archival records of South Carolina’s colonial government, but Governor Blake and his Council of advisors apparently sent at least one copy to the Lords Proprietors along with news of their revised plans. More specifically, I believe their design appears on an undated, rudimentary plat of Charleston that forms part of the John Archdale record book, 1690–1706, which is now held by the Library of Congress.[7]

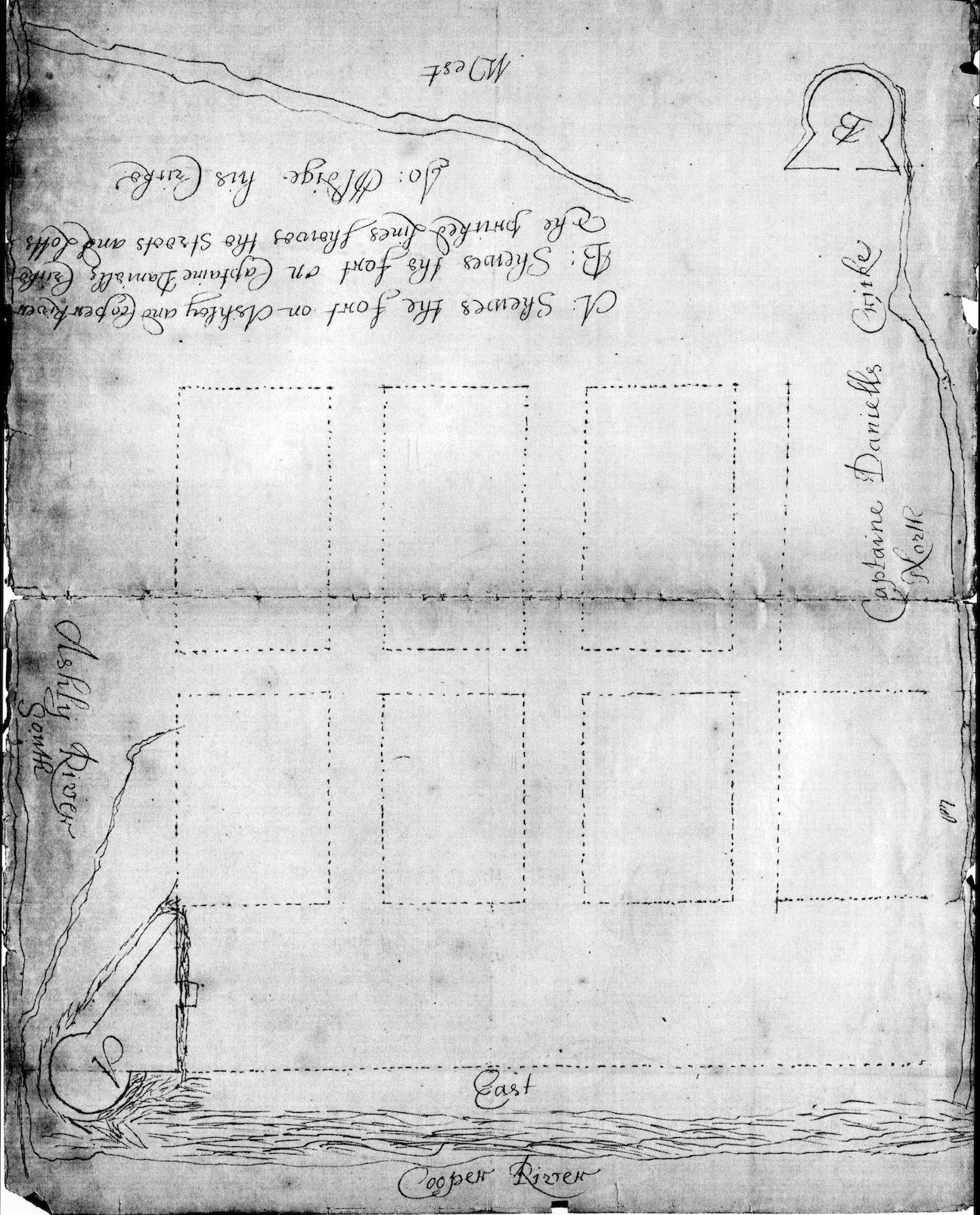

The document in question, identified only as a “Plott of ye Towne,” depicts two detached forts, labeled “A” and “B,” placed at the southeast and northwest corners of urban Charleston, respectively. Both Fort A, situated on the point of sand to the north of Collins’s Creek, and Fort B at the western end of Daniel’s Creek (now Market Street), are drawn as irregular structures formed by the intersection of a circle and a triangle. These awkwardly asymmetrical forms, which would have been ineffective for defensive purposes, must have been designed by someone unfamiliar with the rules of standardized military architecture as practiced across Europe and the American colonies during the second half of the seventeenth century. Nevertheless, the South Carolina fortification commissioners apparently endorsed the construction of the fort labeled “A” in December 1696 or shortly thereafter. This theory is confirmed in the spring of 1697, when the provincial legislature resolved to cancel this awkward design.[8]

After adjourning for a holiday recess in early December, the Commons House reconvened in Charleston on February 23rd, 1696/7. Governor Blake once again opened the legislative session by reminding the House to attend to the fortifications and the tax revenue that had accrued to that project over the past eleven months. Echoing the events of the previous session, some unknown members of the elected assembly expressed misgivings about the design recently adopted by the commissioners appointed to superintend the fortification. The amateurish form of the proposed work, consisting of a half-moon attached to a triangle, might prove less effective than a more regular and professional plan. To address these concerns, the Commons House on February 26th ordered a new committee to meet immediately with the commissioners for “building the ffortt,” to converse “about the forme of the ffortification agreed upon by the sd Commssionrs: and wth them to advise whether the sd forme be a convenient defence for this place and report the same to this House.”

Later than same day, the committee returned to the Commons House and delivered a brief report. They apparently illustrated their presentation by displaying a copy of the design proposed by the commissioners, which was likely identical to the aforementioned plat now found within the Archdale record book at the Library of Congress. Having considered the matter in consultation with the commissioners, the committee recommended to the Commons “that there be a ffortification in the place assigned by Act of Assembly, and that from the platt of the ffortification allready made, the halfe moone be taken away and that there be no port holes [i.e., embrasures], butt the gunns to play over the wall.”[9] The removal of the circular element from the design left what was essentially a free-standing right triangle of limited defensive value. If any legislators objected to this change, their remarks were deferred to the following day.

Later than same day, the committee returned to the Commons House and delivered a brief report. They apparently illustrated their presentation by displaying a copy of the design proposed by the commissioners, which was likely identical to the aforementioned plat now found within the Archdale record book at the Library of Congress. Having considered the matter in consultation with the commissioners, the committee recommended to the Commons “that there be a ffortification in the place assigned by Act of Assembly, and that from the platt of the ffortification allready made, the halfe moone be taken away and that there be no port holes [i.e., embrasures], butt the gunns to play over the wall.”[9] The removal of the circular element from the design left what was essentially a free-standing right triangle of limited defensive value. If any legislators objected to this change, their remarks were deferred to the following day.

An unrecorded debate of the pros and cons of the fortification design took place within the Commons House on the morning of February 27th. The committee had already recommended changes to the proposed plan, but some members felt that the entire design was conceptually flawed. At the conclusion of the debate, the members of the House resolved that the fortification “be not built according to the platt thereof already appoynted and that in the place there of there be made a battrey.” The Commons then sent notice of their resolution to the Upper House of Assembly, which immediately responded by assenting to the proposed change. The Speaker of the House then appointed a new committee to join with a committee of the Upper House “to call to their assistance any other person or persons they shall thinke fitt and advise & consult of the forme of a battrey to be made in the place of a fortification, and a platt of the sd battery to lay downe in paper and report ye same to this House.”[10]

The textual context of the debate of February 27th implies that the legislators desired a new design that differed fundamentally from the one already submitted, but the precise nature of that substitute structure is clouded by their imprecise and often interchangeable use of architectural terminology. In the context of military architecture, the term “battery” usually denotes a grouping or cluster of artillery, which might reside within a detached structure or form part of a larger fortified landscape. The irregular plan proposed in early 1697, featuring a half-moon mashed against a right triangle, could technically be construed as a detached battery, but that design was wholly rejected on February 27th. Subsequent legislative discussions of this topic use the terms battery, fort, and bastion interchangeably, however, providing clues to interpret the desired object. It appears that the legislators sought to replace the proposed irregular structure with an artillery battery designed according to contemporary professional standards that would form part of a larger and more conventional fortified structure. In short, I believe they sought to construct one bastion of a larger fort.

On March 2nd, after a few days of intense design work, the fortification committee returned to the Commons House with news of a significant development couched within a brief statement. They reported simply that the members of the joint conference “had agreed to ye forme of [a] Battery and laid downe a platt thereof which they presented to this House.”[11] That plat does not survive among the records of South Carolina’s colonial government, but I believe we can identify copies held at two distant archives. The first appears within the aforementioned record book of John Archdale at the Library of Congress. There we find an undated line drawing, labeled “The Draughts of the Forts,” which depicts two nearly-identical quadrangular forts differing only in scale. Although nothing in this plat confirms its connection to South Carolina beyond its association with John Archdale, an identical manuscript copy of the same two forts, drawn by the same hand, is found at the Bodleian Library at Oxford University, and bears the caption “A draught of ye forts of Carolina.”[12]

On March 2nd, after a few days of intense design work, the fortification committee returned to the Commons House with news of a significant development couched within a brief statement. They reported simply that the members of the joint conference “had agreed to ye forme of [a] Battery and laid downe a platt thereof which they presented to this House.”[11] That plat does not survive among the records of South Carolina’s colonial government, but I believe we can identify copies held at two distant archives. The first appears within the aforementioned record book of John Archdale at the Library of Congress. There we find an undated line drawing, labeled “The Draughts of the Forts,” which depicts two nearly-identical quadrangular forts differing only in scale. Although nothing in this plat confirms its connection to South Carolina beyond its association with John Archdale, an identical manuscript copy of the same two forts, drawn by the same hand, is found at the Bodleian Library at Oxford University, and bears the caption “A draught of ye forts of Carolina.”[12]

In contrast to the asymmetrical plan adopted by the fortification commissioners at the end of 1696, the symmetrical four-bastion forts illustrated in the Archdale and Oxford plats reflect the geometric discipline that characterized professional military architecture of the late seventeenth century. It seems that the commissioners and the joint committees of the bicameral legislature benefitted from the advice of some local inhabitants who were more knowledgeable about fortification design. Reaching forward to the documentary evidence of a similar fortification episode in late 1703, I believe that the provincial government likely consulted with members of Charleston’s French Huguenot community who were familiar with the geometric designs of the contemporary French engineer Sébastien de Vauban (1633–1707).

If the Archdale and Oxford plats do, in fact, depict the design presented to the South Carolina Commons House on March 2nd, 1696/7, then we can conclude that local authorities abandoned the idea of building a relatively small, self-contained fortification and embraced the construction a larger structure composed of several distinct but interconnected parts. More specifically, the revised design endorsed in March 1697 corresponds to the larger of the two forts depicted on the Archdale and Oxford plats, which includes four symmetrical bastions, each connected to its neighbor by a curtain wall measuring 100 feet in length. A small but significant clue supporting this theory appears in the continuation of the design conversation that was recorded within the journal of the Commons House of Assembly on March 2nd. “Upon debate of ye sd fforme and platt thereof,” the Commons House ordered “that the ffront line of the sd battery be extended 20 ffeete soe yt ye sd line containe 120 ffeete in all and the said committe draw a platt accordingly and call to their assistance whome they shall thinke fitt and lay out ye ground for the sd battery.”[13]

Within a week of endorsing an enlarged version of the new fortification design, the South Carolina Commons House was in possession of a now-lost paper copy the revised plan. On March 9th, the House signaled its final approval by ordering “that the com[missione]rs for building ye ffortefication do cary on and build the battery according to a platt thereof brought into this House.” The Upper House of Assembly gave its assent to the plan later the same day, followed by the signature of Governor Joseph Blake.[14] Work on the much-anticipated fortification commenced immediately, but the surviving government records of this era contain no further mention of fortifications until the autumn of 1700. From that time forward, legislative conversations about the defense of urban Charleston contain no references to the four-bastioned fort authorized in the spring of 1697. The work was apparently never completed, and it soon faded from the town’s collective memory.

Within a week of endorsing an enlarged version of the new fortification design, the South Carolina Commons House was in possession of a now-lost paper copy the revised plan. On March 9th, the House signaled its final approval by ordering “that the com[missione]rs for building ye ffortefication do cary on and build the battery according to a platt thereof brought into this House.” The Upper House of Assembly gave its assent to the plan later the same day, followed by the signature of Governor Joseph Blake.[14] Work on the much-anticipated fortification commenced immediately, but the surviving government records of this era contain no further mention of fortifications until the autumn of 1700. From that time forward, legislative conversations about the defense of urban Charleston contain no references to the four-bastioned fort authorized in the spring of 1697. The work was apparently never completed, and it soon faded from the town’s collective memory.

The mystery of the disappearing fort of 1697 has perplexed me for more than a decade. I’ve reviewed the available evidence countless times, and I’ve questioned whether or not the aforementioned Archdale plats have any bearing on this topic. After careful review, however, I believe that we can resolve this conundrum by considering the extant documentary clues in conjunction with the physical remnants of the fortifications built more than three centuries ago. I’ll offer my current hypothesis a sort of summary heading towards a conclusion of this episode:

In the spring of 1697, during a period of great anxiety about defensive preparedness, the South Carolina government dismissed a plan to build a relatively compact and self-contained fortification in favor of a larger and more expensive fort that would require more time and money to complete. The rationale behind this seemingly contradictory logic lies within the modular nature of the larger and more expensive fort. While the completion of the four-bastion design adopted in 1697 would ultimately afford significant defense to the future citizens of urban Charleston, the construction of even just one of its diamond-shaped bastions would provide adequate protection during an emergency. The frugal civic leaders of that era decided to advance the ambitious defensive work in stages and build the remaining bastions and curtain walls as money, materials, and labor became available.

Confirmation of this theory appears shortly after the South Carolina General Assembly adjourned for the season on March 10th, 1696/7. In a letter to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, dated March 24th, Governor Blake and the members of his advisory Council proudly announced the results of the most recent legislative session. After several years of prodding and debate, the colonists had inaugurated a modular plan for building a permanent fortification that, when completed, would compare favorably with other examples of the most robust contemporary designs: “Wee are now hard att work abt: a fortificacon att Charles Towne which wee hope in a little time to make servicable and to leave it so as when wee can raise money to do it with, it may bee made as regular and fformidable as any such woorke in America.”[15] I believe the large quadrangular fort depicted in the aforementioned Archdale and Oxford plats represents the design of the “regular and fformidable” structure intended to be built in 1697.

Confirmation of this theory appears shortly after the South Carolina General Assembly adjourned for the season on March 10th, 1696/7. In a letter to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, dated March 24th, Governor Blake and the members of his advisory Council proudly announced the results of the most recent legislative session. After several years of prodding and debate, the colonists had inaugurated a modular plan for building a permanent fortification that, when completed, would compare favorably with other examples of the most robust contemporary designs: “Wee are now hard att work abt: a fortificacon att Charles Towne which wee hope in a little time to make servicable and to leave it so as when wee can raise money to do it with, it may bee made as regular and fformidable as any such woorke in America.”[15] I believe the large quadrangular fort depicted in the aforementioned Archdale and Oxford plats represents the design of the “regular and fformidable” structure intended to be built in 1697.

The Lords Proprietors responded several months later by congratulating Governor Blake on the defensive progress: “Wee are very well pleased to heare you are so forward in yor fortifications and hope you will press it so as to make Charles Town (and that will make your countrey) secure.”[16] Due to a series of subsequent events and circumstances, however, the “regular and fformidable” four-bastion structure was never completed. The Treaty of Ryswick ended King William’s long war with France in the autumn of 1697. The Lords Proprietors communicated this news to South Carolina that December and advised Governor Blake to persevere with the defensive works. Although peace had been proclaimed, said the Proprietors, “wee would not have that slacken your intentions of fortifyeing.”[17]

But slacken they did. Between January 1698 and September 1700, the inhabitants of Charleston experienced repeated episodes of a deadly distemper, an earthquake, a major fire that consumed a third of the town, and a ferocious hurricane the wrecked the waterfront and claimed many lives. The provincial legislature reconvened in the autumn of 1700 and inaugurated a new chapter of fortification construction that revolved around the brick “battery” that had commenced in the spring of 1697. What was originally intended as the first component of a four-bastioned fort became the principal town battery during a period of peace across the colonies. When Europe again erupted with international warfare in 1703, the lone brick bastion became the cornerstone of an emergency effort to encircle the town with hastily constructed earthen walls. By the end of 1708, locals had named it Granville Bastion, in honor of the reigning Palatine or chief of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, and the rest, as they say, is history.[18]

But slacken they did. Between January 1698 and September 1700, the inhabitants of Charleston experienced repeated episodes of a deadly distemper, an earthquake, a major fire that consumed a third of the town, and a ferocious hurricane the wrecked the waterfront and claimed many lives. The provincial legislature reconvened in the autumn of 1700 and inaugurated a new chapter of fortification construction that revolved around the brick “battery” that had commenced in the spring of 1697. What was originally intended as the first component of a four-bastioned fort became the principal town battery during a period of peace across the colonies. When Europe again erupted with international warfare in 1703, the lone brick bastion became the cornerstone of an emergency effort to encircle the town with hastily constructed earthen walls. By the end of 1708, locals had named it Granville Bastion, in honor of the reigning Palatine or chief of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, and the rest, as they say, is history.[18]

I’ll offer one physical fact to pin down the interpretations presented here. The surviving brickwork of Granville Bastion, following its partial demolition in the late 1780s, is visible in the basement of the Missroon House at 40 East Bay Street. The remnants include the entirety of the bastion’s eastern face, which measures 89 feet in length, and an adjacent flanking wall, 27.5 feet long, that connects it to the curtain wall on the east side of East Bay Street. Reference to the large fort illustrated in the Archdale and Oxford plans demonstrates that the length of the proposed bastion face was 86.5 feet and the adjacent flanking wall was 27.5 feet. The slight difference between these dimensions can be attributed to the more acute angle of the flanking wall that was built here in the late 1690s.[19]

We’ll continue this conversation about the urban fortifications of colonial Charleston in future programs in conjunction with the Mayor’s Walled City Task Force. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with a final thought to fuel the time machine between your ears. If the South Carolina government had completed the fort plan endorsed in the spring of 1697, with a curtain wall extended to 120 feet in length, the finished structure would have measured nearly 300 feet square and encompassed more than two acres of prime real estate along the Cooper River waterfront, from the “poynt of sand” next to the present Missroon House to the north side of the Carolina Yacht Club. In short, it would have been nearly identical in size and shape to the surviving Spanish fort at St. Augustine, the Castillo de San Marcos, which was completed in 1695. Was this similarity coincidental or intentional?

[1] A. S. Salley, Jr., ed., Journal of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina For the Session Beginning November 24, 1696, and Ending December 5, 1696 (Columbia: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1912), 4–5. The committee included Jonathan Amory (speaker of the House), Captain Job Howes, Captain George Raynor, and provincial gunner William Smith. In this and other quotations cited in this essay, I have reproduced the original spelling. In this excerpt, however, I have removed several unnecessary commas.

[2] Susan Baldwin Bates and Harriott Cheves Leland, Proprietary Records of South Carolina, Volume Three: Abstracts of the Records of the Surveyor General of the Province, Charles Towne 1678–1698 (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2007), 43.

[3] Salley, Journals of the Commons House, 1696, 6.

[4] Salley, Journals of the Commons House, 1696, 7.

[5] Salley, Journals of the Commons House, 1696, 7. The committee included Ralph Izard, Robert Stevens, and Daniel Courtise. Information about the French design against Charleston appears in a letter from the South Carolina Council to the Lords Proprietors, dated 6 December 1696, in A. S. Salley, Jr., ed., Commissions and Instructions from the Lords Proprietors of Carolina to Public Officials of South Carolina, 1685–1715 (Columbia, S.C.: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1916), 100–1.

[6] Act No. 147, “An Act for building a fortification at Charles Town,” ratified on 5 December 1696. The text of this act was not included in the nineteenth-century compilation of The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, but the original document survives among the engrossed Acts of the General Assembly at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH).

[7] A microfilm copy of the John Archdale record book, 1690–1706, is held at SCDAH, from which I have extracted the images presented here.

[8] The commissioners appointed to execute the fortification act of March 1695/6, and the revised version of December 1696, included the governor (ex officio), Sir Nathaniel Johnson, Lieutenant General Joseph Blake, Landgrave Joseph Morton, Captain James Moore, Colonel Hopson Bull, Captain William Hawett, Captain Charles Basden, Captain William Smith, Jonathan Amory, William Smith (merchant), Edward Rawlings, and David Maybank.

[9] A. S. Salley, Jr., ed., Journals of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina For the Two Sessions of 1697 (Columbia: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1913), 8. The committee included Captain Job Howes, Captain George Raynor, Captain John Clifford, and James Witter.

[10] Salley, Journals of the Commons House, 1697, 9. The committee included Captain Job Howes, Captain John Clifford, James Witter, and Daniel Courtise.

[11] Salley, Journals of the Commons House, 1697, 10.

[12] Oxford University, Bodleian Library, MS. Rawlinson B. 243, folio 15 recto.

[13] Salley, Journals of the Commons House, 1697, 10.

[14] Salley, Journals of the Commons House, 1697, 16.

[15] Salley, Commissions and Instructions, 102.

[16] Lords Proprietors to Joseph Blake, 30 August 1697, transcribed in A. S. Salley, et al., eds., Records in the British Public Record Office Relating to South Carolina, 1691–1697 (Atlanta, Ga.: Foote & Davies Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1931), 216.

[17] Lords Proprietors to Joseph Blake, 20 December 1697, transcribed in Salley, Records in the British Public Record Office Relating to South Carolina, 1691–1697, 236.

[18] See Episode No. 74 for information about the demolition of Charleston’s colonial fortifications.

[19] I have personally examined the remnants of Granville Bastion under the Missroon House, and can recommend two measured drawings of the surviving brickwork. See the plat surveyed on 12 May 1789 by Barnard Beekman, attached to the deed of Hary Grant to Francis Kinloch, mortgage by lease and release, 15–16 December 1795, in Charleston County Register of Deeds, Q6: 60–67. See also Samuel Lapham, “Notes on Granville’s Bastion (1704),” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 26 (October 1925): 221–27.

NEXT: Captain Thomas Hayward’s Poetic Description of 1769 Charles Town

PREVIOUSLY: Charleston County’s Mobile Library Service, 1931–2021

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments