The Golden Christmas of 1852

Processing Request

Processing Request

If you’ve ever wondered what Christmas was like on a Lowcountry plantation in Antebellum times, William Gilmore Simms has the answers. His 1852 novella, The Golden Christmas, is a lighthearted, sunny tale of romance and comedy that floats carelessly above the thinly-veiled darkness of slavery. Although it contains some valuable insights into Antebellum culture, there’s a reason why this book is not a holiday classic. Today we’ll take a quick overview of its author, its storyline, and its fatal flaws, and then sample a bite-sized portion of The Golden Christmas as a holiday treat.

William Gilmore Simms was born in Charleston in 1806 to parents of Scots-Irish descent, and he died in the city in 1870. In his youth he studied law, but Simms chose to pursue a career as a writer instead. He published his first short work in 1825, at the age of 19, then passed the bar at the age of 21, and then went back to writing. During his long literary career, Simms published short stories and some poetry, but he is remembered primarily as a novelist, and secondly as a historian. In fact, these fields often overlap in his work. Most of his novels are set in earlier periods of South Carolina history, especially during the colonial and Revolutionary eras. His fascination with local history also bore fruit in the 1842 publication of a monograph titled simply History of South Carolina, which served for several generations as the standard school textbook on the state’s history.

It is important to acknowledge, however, that William Gilmore Simms was also an ardent defender of slavery and a strong supporter of South Carolina’s secession from the United States. His literary heroes and heroines are generally affluent white Southerners whose privileged lifestyles are made possible by the labors of silent, mostly nameless “servants” who toil contentedly in the background. While the defense of slavery is never his central theme, Simms did not hesitate to depict the “happy slave” when the story line provided an opportunity to do so. This paternalistic nonsense is present even in Simms’s lighthearted holiday novella, The Golden Christmas: A Chronicle of St. John’s, Berkeley, which was published in Charleston in 1852. Today’s short podcast isn’t the proper forum for a detailed critique of the book’s eighteen chapters, of course. Rather, I’d like to give you a reader’s-digest overview of The Golden Christmas, point out a few of its flaws and novelties, and then read some excerpts from the final chapters that describe the details of a Christmas holiday celebration, as it was done by wealthy plantation owners in the Lowcountry of South Carolina in the years just before the Civil War.

The Golden Christmas is set in and around Charleston, in the weeks leading up to Christmas. The basic premise of the book is this: two young, affluent bachelors are looking for wives during the holiday season. Think of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, but full of stereotypical Southern manners, a bit of comedy, and of course a happy ending. The main plot line concerns the budding romance between Edward, or Ned Bulmer, the scion of an old English family in South Carolina, and young Paula Bonneau, whose family are descended from French Huguenots who settled here in the early days of Carolina. The young lovers are determined to be married, but their families don’t move in the same social circles, and in fact have been feuding for a hundred years. The secondary plot line concerns the book’s first-person narrator, named Dick Cooper, who is in love with Miss Beatrice Mazyck, the young beauty of another ancient Huguenot family.

The Golden Christmas is set in and around Charleston, in the weeks leading up to Christmas. The basic premise of the book is this: two young, affluent bachelors are looking for wives during the holiday season. Think of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, but full of stereotypical Southern manners, a bit of comedy, and of course a happy ending. The main plot line concerns the budding romance between Edward, or Ned Bulmer, the scion of an old English family in South Carolina, and young Paula Bonneau, whose family are descended from French Huguenots who settled here in the early days of Carolina. The young lovers are determined to be married, but their families don’t move in the same social circles, and in fact have been feuding for a hundred years. The secondary plot line concerns the book’s first-person narrator, named Dick Cooper, who is in love with Miss Beatrice Mazyck, the young beauty of another ancient Huguenot family.

In the course of the story, we roam around the Lowcountry with this quartet, the young bucks Ned and Dick looking for opportunities to court the young, beautiful, and bewitching Paula and Beatrice. We go shopping on King Street, chase wild boar through the swamps of Berkeley County, attend family gatherings on plantations, and listen to the whispers of family arguments about who is, and who is not, an appropriate beau for a young lady of a certain social station. In the end, the Huguenot elders, Paula’s mother, Madame Agnes-Theresa, and Beatrice’s mother, Mrs. Mazyck, warm up to the charms of Ned Bulmer and Dick Cooper. Their respective families gather together to celebrate the Christmas holiday at Ned’s family estate, Bulmer Barony, in the parish of St. John’s, Berkeley. At the barony’s big house, our host is Ned’s eccentric father, called Major Bulmer, and his spinster sister, whom Ned calls Aunt Janet.

Throughout the novella, a few members of the enslaved supporting cast occasionally step across the page in the performance of their customary roles as waiters, footmen, grooms, cooks, cleaners, et cetera. Simms’s description of their appearance, manners, and speech is generally as ridiculous and offensive as you might expect from a white slaveholder of the 1850s. For this reason, The Golden Christmas, regardless of its literary merit, will never be a holiday classic, and will certainly never be transformed into a made-for-TV-movie. In the final chapter, set on Christmas day, for example, we actually follow “Father Chrystmasse” on a visit to a slave cabin, where he distributes a few baubles to the “happy people” who live in impoverished servitude, “absolutely free from care.” In this overtly-paternalistic scene, Simms even includes a visiting Yankee, full of “stupid prejudices” about their condition, in order to witness his opinion transformed by observing “that inevitable charity which characterizes the institution of Southern slavery.”

In the spirit of peace and harmony, let’s turn away from Simms’s overt racism and focus on the holiday traditions depicted in The Golden Christmas. Before we hear a bit of the story, I want to draw your attention to two interesting points. First, there is a Christmas tree in this novel. That fact may not surprise audiences today, but it’s important to realize that in 1852 the Christmas tree was a very new addition to holiday celebrations in South Carolina. Through letters written by Simms and others, we know that the tradition of erecting an indoor evergreen tree was introduced here by the Swedish vocalist, Jenny Lind, who was performing in Charleston in December of 1850. Second, in this story, the author goes out of his way to point out some differences between the English and Dutch traditions surrounding Christmas. In the old English tradition, the holiday is primarily for adults, with festive merry-making, lavish eating, and mistletoe. “Father Chrystmasse” visits to remind everyone to celebrate the birth of Jesus. The Puritans of New England, who shunned adult merriment, were responsible for relegating Christmas to children, says Simms, and they brought over the gift-giving Dutch St. Nicholas, who Simms calls “the dapper little Manhattan goblin.”

But enough of my introduction. Let’s turn to chapter sixteen of The Golden Christmas, by William Gilmore Simms, and let his narrator, Dick Cooper, describe the holiday festivities.

--------------------------------------------------

Chapter XVI: Christmas Eve.

Time, meanwhile, had been hobbling forward, after the usual fashion, and with his wonted rapidity. He brings us at length to Christmas eve. . . . Major Bulmer has failed in none of his supplies; and aunt Janet has been doing the crusty in spite of her proverbial sweetness of temper,—and because of it—in the pantry and bake-house, for a week of eleven days. What a wilderness of mince-pies have issued from her framing hands; what a forest of patties and petties, cocoanut and cranberry;—what deserts of island and trifle; what seas of jelly; what mountains of blanc mange. Eggs have grown miraculously scarce. There is a hubbub now going on between the fair spinster and her lordly brother.

Time, meanwhile, had been hobbling forward, after the usual fashion, and with his wonted rapidity. He brings us at length to Christmas eve. . . . Major Bulmer has failed in none of his supplies; and aunt Janet has been doing the crusty in spite of her proverbial sweetness of temper,—and because of it—in the pantry and bake-house, for a week of eleven days. What a wilderness of mince-pies have issued from her framing hands; what a forest of patties and petties, cocoanut and cranberry;—what deserts of island and trifle; what seas of jelly; what mountains of blanc mange. Eggs have grown miraculously scarce. There is a hubbub now going on between the fair spinster and her lordly brother.

“But, Janet, by Jove, this will never do! You mustn’t stint us in Egg-nog. Better give up a bushel of your pudding stuff, than that we should have less than several bushels of eggs.”

“But, brother, there will still be enough. You know the ladies seldom take egg-nog, now a days.”

“I know no such thing, and don’t believe it. We must provide enough, at all events. Send out Tom and Jerry; let them scour the country and pick up all they can. These women with their parties!”

“Was ever such a man as brother!” cried Miss Janet to me, with bare arms, uplift, and well sprinkled with flour. She had been kneading that her public should not need, which is certainly patriotism, if not Christian charity. But I have no time to listen to her, or to speculate upon her virtues. The Major summoned me forth to look at the hogs. Thirty were slaughtered last night. There they hang, the long-bodied, white porkers, thoroughly cleaned, like so many convicts, decently dressed for the first time in their lives, when about to pay the penalty of their offences. “Not a rogue among them,” quoth the Major, “that weighs less than 250 [pounds] nett.” Yesterday, there was a beef shot. We must go and look at him, see him quartered, and estimate his weight and importance also. Huge tubs and wooden platters of sausage meat entreat our attention, and I assist Miss Janet in measuring out pepper, black and red, and sage and thyme, and salt and saltpetre, that the sausage meat may be as grateful to the taste as it is fully great to the eye. The Major and his sister are the busiest people in the world. Ned Bulmer is abroad and busy also, as much so as he can be, his arm in a sling [following a hunting accident]. He is anxious about certain oysters ordered from the city, and is pacified by the response from the gentlemanly body servant,—“The oysters have arrive, Mr. Edward, in good order.” Boxes are to be unpacked, in which I help. Miss Janet is feverish about the fate of several barrels of crockery. I assist in relieving her. The Major needs my help in opening and unfolding certain cases of fire-works, and in preparing sockets for rockets, and reels for wheels, posts, and platforms, &c., for a display by night. Our Baron, like other Princes, is fond of, and famous for, his pyrotechny. . . .

The fire-works arranged and disposed of, we turned in upon a Christmas Tree, which was to be elevated within the great hall. This was a beautiful cedar, carefully selected, and brought in from the woods, the roots well fitted into the half of a huge barrel, rammed with moss, the base being so draped with green cloth as to conceal the rudeness of the fixture. This, planted and adjusted in its place, we enclosed the piazza, front and rear, with canvas, and hung the interior in both regions with little glass lamps of different colours. Half of the day, Christmas eve, was employed in these and a score of other performances. Nothing that we could think of was omitted. Then, there were boxes of toys for the children to be unpacked, and trunks of pretty presents to be examined, and the names written on them of the persons for whom they were designed. They were, that night, after the guests had all retired, to be suspended to the branches of the Christmas Tree, which was, in the meanwhile, to be kept from sight by the dropping of a curtain across the hall! Ned Bulmer had his gifts prepared, as well as his sister and aunt. I, too, had bought my petty contributions, calculating on the persons I should meet.

Before noon, the company began to pour in. Several came to dinner that day. Afternoon brought sundry more, who were to spend the night, and perhaps several nights. The mansion house was entirely surrendered to the ladies and married people;—the young men were entirely dispossessed and driven to sheds and out-houses, in which, fortunately, ‘the Barony’ was not deficient. Ned and myself lodged with the over-seer, and had a snug apartment to ourselves. At dinner, it was already necessary to spread two tables. Every body was becomingly amiable. Care was kicked under the table, and lay crouching there, silent and trembling, like a beaten hound, not daring to crunch even his own bones aloud. The ladies smiled graciously to our sentiments, and we had funny songs and stories when they had gone. After dinner, some of the guests rode or rambled for an hour, others retired to the library,—chess and backgammon; others to the chambers;—and the work of preparation still went on. The holly and the cedar, twined together with bunches of the ‘Druid Mistleto,’ wreathed the doors and windows, the fire-place, the pictures. Red and blue berries glimmered prettily among the green leaves. At night, we had the tea served sooner than usual, for the Major was impatient for the fire-works. The discharge of a cannon was the signal for crowding to the front piazza. There, as far as the eye could extend, ranging along the green avenue, at equal distances, were piles of flaming lightwood, showing the way to the dwelling. They failed to show the spectators where the Major was preparing for his rockets. Suddenly, these shot up amid the darkness; a flight of a dozen, with the rush of the seraphim, flying, as it were, from the glooms and sorrows of the earth. Then came wheels, Roman candles, frogs, serpents, and transparencies—quite a display, and doing great credit to the Major, besides singing his cheek and hair, and drawing an ounce of blood from his left nostril—the result of a premature and most indiscreet explosion of a turbillon, or something of the sort. But this small annoyance was rather agreeable than otherwise, as tending somewhat to dignify the exploit.

The display over, and the spectators somewhat cooled by standing in the open air, we returned to the rooms and the violin began to infuse its own spirit into the heels of the company. Then followed the dances; quadrilles, cotillon, country dances, Virginny reels, and regular shake-downs. We occupied two saloons at this business till 12 o’clock, when the boys and girls, obeying the signal of Miss Janet, descended to the rooms assigned to offices purely domestic. Huge bowls might here be seen displayed, and mammoth dishes. A great basket of eggs was lifted in sight, and upon a table. Knives and forks, sticks and goose feathers, were put in requisition. Eggs were poised aloft and adroitly cut in twain; the yolk falling into the bowl, the white into the dish—separating each, as it were, with a becoming sense of what was expected of it. Then the clatter that followed,—the rubbing and the rounding,—the twitching and the clashing! How fair arms flashed, even to the elbow, and strong arms wearied, even to the shoulder blade, to the merriment and mockery of the damsels. . . . At length, the huge tray being uplifted, turned upside down, and the white mass clinging still solidly to the China, it was pronounced the proper moment for reuniting the parties so recently separated. Then rose the golden liquid, a frosted sea of strength and sweetness and serenity, that never whispered a syllable of the subtlety that lurked, hidden in the compound, born of the glowing embraces of lordly Jamaica and gallant Cognac. Lo! now the strong-armed youth, as they bear the glorious beverage on silver salvers to the favourite ladies. They quaff, they sip, they smile, they laugh; the brightness gathers in their eyes; they sparkle; the orbs dance like young stars on a frosty night, as if to warm themselves;—when suddenly, Miss Janet rises, stands for a moment silent, looks significantly around her, and is understood! A gay buzz follows; and, with smiles and bows, and merry laughter, and pleasant promises, the gay group disappears, leaving the tougher gender to finish the discussion of that bright, potent beverage, in which the innocent egg is made to apologize for a more fiery spirit than ever entered into the imagination of pullet to conceive! Merry were the clamours that followed;—gay songs were sung;—some of the youngsters, just from college, took the floor in a stag dance;—while half a dozen more sallied forth at one o’clock, called up the dogs, mounted their steeds, and dashed through the woods on a fox hunt. But the fox they hunted that night was one of that sort which Sampson let loose among the Philistines—a burning brand under his brush—not suffering him to know where he ran!

Chapter XVII: Christmas—How Golden.

Christmas Dawn! The day opened with bursting of bombs from the laboratory of Major Bulmer. He was up and at work, bright and early, having summoned me to his assistance. In fact neither of us had done much sleeping that night. We had employed more than an hour of the interval, after the termination of the dance, in arranging the gifts among the branches of the cedar, and in other matters. Then we had adjourned to an out-house, where the Major kept his fire-works, and had gotten the explosive pieces in readiness. They did famous execution when discharged, routing every body out of his sleep, though it should be as sound as that of the Famous Seven! The children were all alive in an instant.

Christmas Dawn! The day opened with bursting of bombs from the laboratory of Major Bulmer. He was up and at work, bright and early, having summoned me to his assistance. In fact neither of us had done much sleeping that night. We had employed more than an hour of the interval, after the termination of the dance, in arranging the gifts among the branches of the cedar, and in other matters. Then we had adjourned to an out-house, where the Major kept his fire-works, and had gotten the explosive pieces in readiness. They did famous execution when discharged, routing every body out of his sleep, though it should be as sound as that of the Famous Seven! The children were all alive in an instant.

“Had old Father Chrystmasse really come.”

There was a rush to the chimney places in every quarter, where, the night before, the stockings and satchels had been suspended from the cedar branches. Dear aunt Janet had taken good care that the “Old Father” should make his appearance; and there was a general shout, as each took down his well-stuffed stocking. Ah! how easy to make children happy—how unexacting the little urchins—how moderate in their desires—how innocent their expectations—how pure, if fervent, their little hopes! . . .

At sunrise that morning, the egg-noggin passed from chamber to chamber. . . . Every guest was required to taste, at all events. The ladies mostly, the dear, delicate young things in particular, were each content with a wine-glass. Some of the matrons could relish a full cup or tumbler, and there were some of these who would occasionally find their way into the contents of a second, and—without getting in their cups! We are to graduate the beverage, be it remembered, according to the capacity of the individual; and he alone is the intemperate—who may add the fool also—who takes a power into the citadel which he cannot keep in due subjection.

The bell rings for breakfast. The hour is late. All are assembled. There is joy in all eyes; merriment in all voices; what a singular conventionalism, established by habits so prolonged, for so many hundred years, by which, whatever the secret care, it is overmastered on this occasion, and the sufferer asserts his freedom for a brief day in the progress of the oppressive time! Breakfast at the ‘Barony’, is, of course, a breakfast for a Prince. Take that for granted, gentle reader, and spare us the necessity to describe. The event over, we group together and disperse. The horses are saddled below. The young gallant lifts his fair one to the saddle. The carriages are ready; and there are parties preparing for a drive. Some of the young men have gone to the woods, pistol and rifle shooting. Others are in the library, companioned by the other sex, at chess and backgammon. We are among these, Ned Bulmer and myself. We have duties at home. We know not what moment will bring to the door our respective favourites. And so, variously engaged and employed, all more or less gratefully, the hours pass until meridian. A little after, the rolling of wheels is heard below. We are at once at the entrance. Major Bulmer is already there. The carriage brings Mrs. Mazyck and her fair daughter. The old lady is not exactly thawed, but the ice is of a thin crust only. The Major tenders her his arm; mine is at the service of Beatrice. Scarcely have we ascended when other vehicles are heard below. It is now Ned’s turn, and while the Major is bowing and supporting Madame Agnes-Theresa, Ned brings in the dear little witch, Paula, hanging on his sound limb, and turning an inquiring and tender glance of interest upon that which pleads for pity from the sling. The Major and his sister divide themselves between the matrons; while Ned and myself share the damsels between us. We slip out, unobserved, for a walk, leaving the ancient quartette in full chase of parish antiquities, recalling old times and making the passing as pleasant by reflection as possible. . . .

We were gone fully two hours from the house, yet, so well had the Major and aunt Janet done their parts, we had not been missed by mamma and grandmamma, and neither frowns nor reproaches waited our return. It was evidently fast proving itself a Golden Christmas. The golden period had come round again as so long promised. The lion and the lamb were about to lie down together. That is,—Major Bulmer, seated in the centre of the sofa, with Madame Agnes-Theresa on one hand, and Mrs. Mazyck on the other, had them both in hand as a dextrous driver two fiery and intractable steeds, whom he has subdued; and the free smile playing upon all three countenances, as we entered, was conclusive of such a conjunction of the planets, as held forth the happiest auguries for the future, in respect to the “currents of true love!”

Company continued to arrive. The groups which had ridden forth returned. The house was thronged. The respectable body-servant looked in at the library. The Major rose, went to the door, looked at his watch, came back, said a few words, by way of apology, to the ladies with whom he had been doing the amiable, and then disappeared. The dinner hour was approaching. It was soon signaled. The Major returned. His arm was tendered to Mrs. Mazyck; Madame Agnes-Theresa was served with that of another ancient Major, quite as conspicuous in the parish as he of Bulmer; and then, each to his mates, we followed all in long procession. Need I say, that, while Ned Bulmer, by singular good fortune, was enabled to escort Paula, by the merest accident, I happened to be nigh enough at the moment to yield my arm to Beatrice. Really, the thing was thoroughly providential in both cases.

Such a dinner! The parish, famous for its dinners, had never seen one like it. It is beyond description. Two enormous tables, occupying the whole length of the spacious dining room, were loaded with every possible form and variety of edible. But the turkey was not allowed, as is usually the case in our country, to usurp the place of honour on this occasion. There was a couple of these birds to each table; but they stood not before the master of the feast. At our entrance, the space on the cloth was vacant at his end of the table. He stood, erect, knife in hand, evidently in expectation. He had one of his famous old English cards to play. One of the turkeys was at one of the tables where I was required to preside, the fair Beatrice on my right. The others were interspersed along the two boards. Presently, we heard solemn music without. Then the door was reopened. and the steward, napkin under chin, made his appearance with an enormous dish.

“My friends,” quoth the Major, in a speech that was evidently prepared, and which we abridge to our dimensions, “I am about to restore a custom common in all the good old English establishments, even within the last hundred years. The turkey has been raised to quite unmerited honour among us. I am willing to assign him his place upon our table; but I shall depose him from the first place hereafter. That properly belongs to the Boar’s Head! The Boar’s Head was the famous dish at Christmas, in old England; not the turkey. The turkey is an innovation. He is purely an American fowl, and was utterly unknown in Europe until after the Spaniards found this continent. He is a respectable bird, particularly in size; but in flavour, cannot rank with the duck, or even a well-dressed young goose. There is no reason why he should supersede the Boar’s Head. I am willing to give him the first place on New Year’s day, as representing a new era and a new country; but on Christmas, as a good Christian, I am bound to stick to the text of the Fathers. . . .

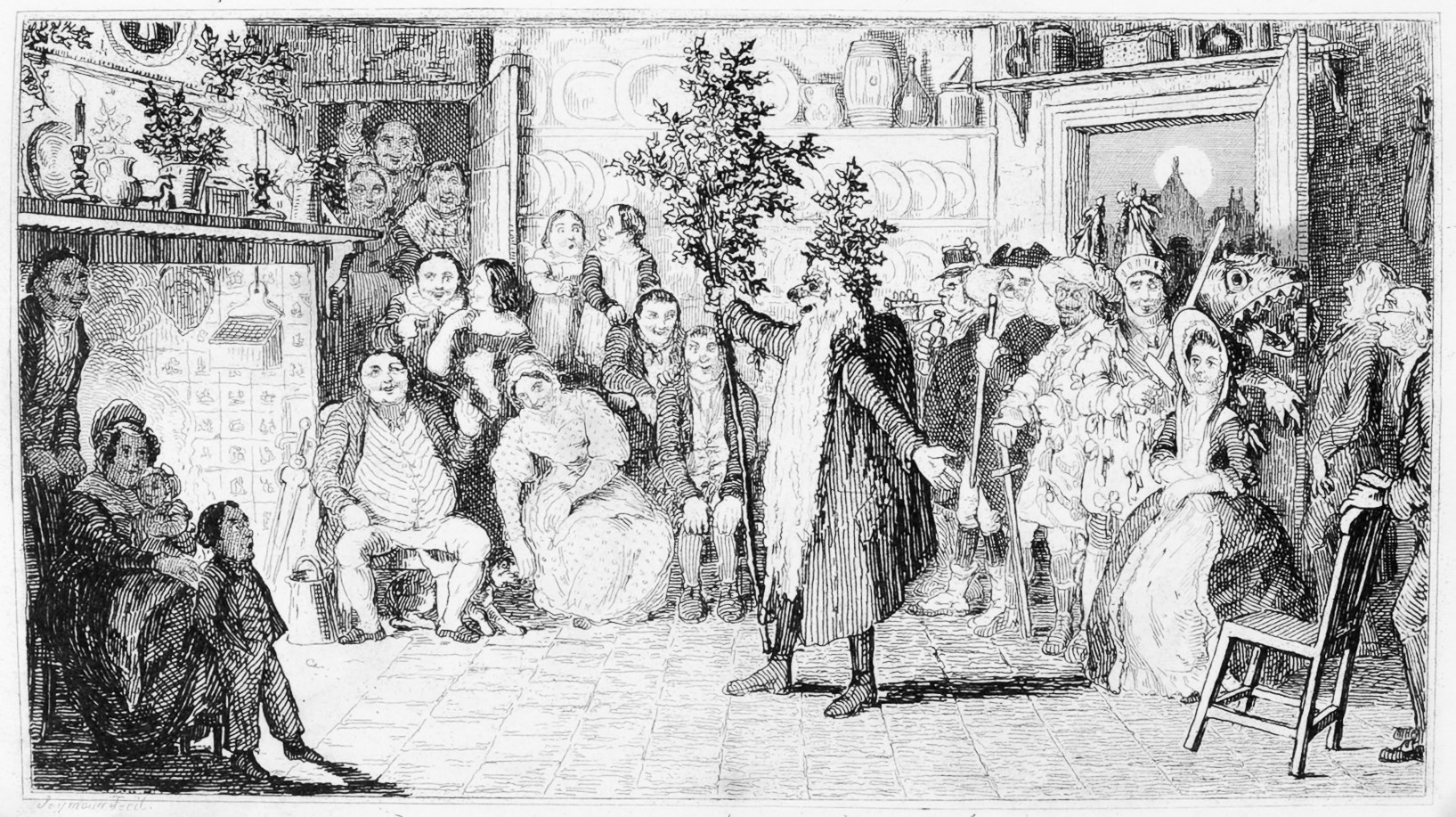

Meanwhile, the Boar’s Head, with a mammoth lemon in his huge jaws, and enveloped in bay leaves and rosemary, was set down in state before us. It was the head of one of the largest of the wild boars that we had slain in our hunt. It was well dressed—it was delicious. Our old English fathers knew what was good; but I am not sure that any of the ladies partook of the savage dish. “Milk for babes, meat for men!” muttered the Major, in a tone between scorn and pity. The feast proceeded, the Baron expatiating occasionally on Boar Heads and Boar Hunts, insisting that, as on every large plantation in the swamp country, wild hogs were numerous, the proper taste required that we should always have the dish for Christmas. I shall not report his several speeches on this and incidental topics. The champagne made its own frequent reports about this time, and left it rather difficult to follow any orator. The Major now drank with Madame Agnes-Theresa; then with the widow Mazyck, and almost made the circuit of the table, in doing grace with the matrons. The younger part of the company were not slow to follow the example. What sweet and significant things were whispered to the several parties beside us—over the wine, but under the rose. The meats disappeared, the comfits took their place, and disappeared in turn. The best of pleasures find their finale at last. Up rose the ladies, and, with a bumper, well drained in their honour, we followed them to the parlour and the library. A brief pause, and a new summons brought us into the hall. The curtain was raised; the Christmas Tree was there in all its glory. The door being closed and the dusk prevailing, the little coloured glass lamps had been lighted among the branches; and, behind the tree, peering over it, raised upon a scaffolding, stood a gigantic figure—a venerable man, fit to be emblematic of the ancient Jupiter, with a fair, full face, large, mild blue eyes, features bold and expressive, yet gentle; but, instead of hair, his head was covered with flowing gray moss, and, from his chin, streaming down upon his breast, the gray moss fell in voluminous breadth and burden. He realized the picture of the British Druid. In one hand he bore a branch of the mistletoe, in the other a long black wand, with a silver crook at the extremity. The children clapped their hands as soon as they saw the figure, and cried out,—“Oh! look at Father Christmas! Father Christmas! Father Christmas!” And they were right. Our saint is an English, not a Dutch saint, be it remembered; and Father Christmas, or the “Lord of Chrystmasse,” as he used to be styled, is a much more respectable person, in our imagination, than the dapper little Manhattan goblin whom they call Santa Claus.

With the clamours of the children, the good father was fully awakened to deeds of benevolence. His crook was in instant exercise. The crook with a gift hanging to it, was immediately stretched out to one after the other—a sweet female voice from the back-ground, naming the little favourite as he or she was required to come forward. When the juveniles were all endowed, they disappeared, to weigh and value their possessions; and the interest began for the more mature. The former voice was silent, and that of a man was heard. He named a lady, then another, and another; and as each was called and presented herself at the foot of the tree, the ancient Druid extended his crook towards her, bearing upon it a box, a bag, or bundle, carefully enveloping the gift, her name being written upon it. Soon the voices from the back ground alternated. Now it was a male, now a female voice, each calling for one or other of the opposite sex, until all the tokens of love and friendship were distributed.

“See,” said Beatrice Mazyck to me,—“see what the Father has bestowed upon me”; and she showed me a lovely pair of bracelets and a breast pin, in uniform style. She did not see, until I showed her, a plain gold ring at the bottom of the box. She looked at it dubiously, and at me dubiously, tried it on every finger but the one, then put it quietly back in the case, and had no more to say on the subject.

But who played the venerable Father, and who played the sweet voices! What matter! Better that the juveniles should suppose that there is an unfamiliar Being, always walking beside them, in whose hands are fairy gifts and favours, as well as birch and bitterness!

____________________________________________________________________

You’ve been listening to excerpts from a novella by William Gilmore Simms, called The Golden Christmas, published in Charleston in 1852. If you’d like to learn more about this book, I invite you to drop by the South Carolina History Room at the Charleston County Public Library, or read the whole text online through The Simms Initiatives at the University of South Carolina. Happy holidays, everyone!

PREVIOUS: The Pirate Executions of 1718

NEXT: Antebellum Charleston’s Most Vulnerable: Foundlings at the Akin Hospital

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments