The Genesis of the Harleston Neighborhood, 1672-1770

Processing Request

Processing Request

The residential area today called Harleston Village is one of the oldest neighborhoods on the Charleston peninsula, but the present definition of its boundaries differs from its original identity. Beginning as a large grant stretching across the peninsula from river to river, north of the town, the Harleston family’s property shrank to a rectangular parcel that was annexed into urban Charleston in 1770 after a series of labored legislative negotiations. From bucolic pasture land to affluent subdivision, Harleston evolved into a highly desirable residential area, though it was never technically a village.

In order to understand the original boundaries of Harleston, we have to rewind to the family’s acquisition of the property in the early days of the Carolina colony. On July 27th, 1672, the governor of Carolina, Sir John Yeamans, issued a warrant directing the Surveyor General, John Culpeper, to lay out a town on Oyster Point, the southern tip of the peninsula at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. On the same day, the governor also ordered Culpeper to lay out the lands immediately north of the town to a number of men who were among the earliest settlers. The surveyor then created a series of individual tracts, each of which stretched across the peninsula from the Ashley to the Cooper River, and proceeded northwardly up the peninsula in succession.

The tract immediately north of the then-unnamed town was granted jointly to John Coming and Henry Hughes, who had arrived in 1670 with the first English immigrants to Carolina. At the time, their tract was estimated to contain 550 acres, but it turned out to be closer to 319 acres. There aren’t any surviving records from the 1670s that record the precise dimension and boundaries of this tract, but later records confirm that it stretched across the peninsula from river to river; bounded on the south by an imaginary line that formed the original northern boundary of Charles Town (now the center line of Beaufain Street and its imaginary continuation to the Cooper River), and on the north by an imaginary line that became Calhoun Street.

Henry Hughes disappeared from the surviving records of South Carolina in the 1670s, and John Coming acquired full title to Henry’s share of their joint grant at some unknown point in the late seventeenth century. Mr. Coming also acquired real estate elsewhere in the Lowcountry of South Carolina, so it’s unclear whether his primary residence was on the Oyster Point peninsula or farther inland, at the “T” of the Cooper River (called Coming’s “T”). After the seat of local government removed from the original settlement at Albemarle point, on the west side of the Ashley River (now Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site) to the present site of “new Charles Town” in 1680, however, John Coming’s peninsular tract became a very attractive possession adjacent to the provincial capital and the hub of all local commerce.

Henry Hughes disappeared from the surviving records of South Carolina in the 1670s, and John Coming acquired full title to Henry’s share of their joint grant at some unknown point in the late seventeenth century. Mr. Coming also acquired real estate elsewhere in the Lowcountry of South Carolina, so it’s unclear whether his primary residence was on the Oyster Point peninsula or farther inland, at the “T” of the Cooper River (called Coming’s “T”). After the seat of local government removed from the original settlement at Albemarle point, on the west side of the Ashley River (now Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site) to the present site of “new Charles Town” in 1680, however, John Coming’s peninsular tract became a very attractive possession adjacent to the provincial capital and the hub of all local commerce.

Through one or more real estate conveyances that were not recorded in any surviving documents, John Coming disposed of more than half of his 1672 land grant at some point prior to his death in 1695. The easternmost part of Coming’s land ended up in the hands of proprietors who later subdivided their properties into the suburban developments called Ansonborough and Rhettsbury. In addition, Mr. Coming or one of his associates sold off a narrow strip of land containing approximately sixteen acres on the west side of the only road leading in and out of colonial Charles Town, then called the “Broad Path” and now called King Street. That strip, bounded today by King Street, Beaufain Street, St. Philip Street, and Calhoun Street, was subsequently subdivided further by several proprietors and developed as several smaller parcels. Although this unnamed strip of land ceased to be part of John Coming’s property portfolio at some unknown point in the late seventeenth century, it played a role in delaying the subdivision of the Harleston neighborhood several generations later.[1]

In his last will and testament in 1694, John Coming left his entire estate to his wife, Affra Harleston Coming (ca. 1625–1699), another of the early Carolina settlers, whom John had married in 1672. English custom dictated that Affra, like all widows, was legally entitled to just a one-third share of her late husband’s property. Because she and John had no children to share the estate, however, Affra needed legal assistance to claim the full scope of her inheritance from Mr. Coming. On November 19th, 1698, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified an act to confirm Affra Coming’s legal title to the full estate of the late John Coming. Immediately after this act, the provincial Commons House of Assembly extended their collective thanks to Mrs. Coming “for her pious and free gift of seaventeene [sic] acres of land adjoyning [sic] to Charles Towne” for the use of the present minister of the town’s Anglican church “and his successors for ever.”[2] In other words, Affra Coming donated a slice off the easternmost part of her peninsular property to establish the glebe land for what became the urban parish of St. Philip. This parcel of seventeen acres, now bounded by St. Philip Street, Beaufain Street, Coming Street, and Calhoun Street, has a long history of its own, but it will return later in this story to play an important role in the birth of Harleston.

In her own will, created just a year after her husband’s death, Affra Coming divided her estate between two nephews who lived beyond the seas. Elias Ball of Devonshire received the plantation at the “T” of the Cooper River (which became Comingtee Plantation), while John Harleston of Dublin received the residue of John Coming’s land adjacent to Charles Town, called Coming’s Point, which contained approximately 130 acres. Affra Harleston Coming died in late 1699, and her nephews arrived in Carolina shortly thereafter to claim their respective inheritances. Several years later, John Harleston of Dublin married Elizabeth Willis here in 1707, and the couple became the parents of one daughter and six sons.[3]

In her own will, created just a year after her husband’s death, Affra Coming divided her estate between two nephews who lived beyond the seas. Elias Ball of Devonshire received the plantation at the “T” of the Cooper River (which became Comingtee Plantation), while John Harleston of Dublin received the residue of John Coming’s land adjacent to Charles Town, called Coming’s Point, which contained approximately 130 acres. Affra Harleston Coming died in late 1699, and her nephews arrived in Carolina shortly thereafter to claim their respective inheritances. Several years later, John Harleston of Dublin married Elizabeth Willis here in 1707, and the couple became the parents of one daughter and six sons.[3]

The lack of detailed family papers frustrate our ability to understand how the Harlestons made use of their large tract of land on the northwest fringes of urban Charles Town during the first half of the eighteenth century, but I have found one clue that might provide a convenient synopsis. In the early months of the year 1750, Elizabeth Harleston, the widow of John the immigrant, advertised in the local newspaper to rent out a tract of 130 acres next to Charles Town. She described the property as “a convenient pasture (for either a butcher or inn-keeper),” which recently had been leased to Mrs. [Mary] Eycott (the wife of a proprietor of a tavern and stable). It would appear, therefore, that the Harlestons did not establish a residence on this land, but rather used the large riverfront property as a grazing pasture for horses and cattle for many decades. Situated on the northwestern outskirts of the colonial capital of South Carolina, and accessible from the Ashley River, the Harleston property was well suited to provide necessary amenities to the people visiting and working in urban Charles Town.[4]

Harleston’s pasture, also called Coming’s Point, was just one of several bucolic tracts lying immediately north of the urban boundary of colonial-era Charles Town. The heirs of the Rhett/Trott family lands on the northeastern edge of the town, for example, likewise rented their property for grazing. Once known as Rhettsbury, it was known in the 1750s as Mr. Lynch’s pasture (see Episode No. 53). Captain George Anson’s property immediately north of Rhettsbury, called “the Bowling Green” in the 1730s and 1740s, was frequently used during that period for pasturage as well as a recreational greenspace. As the local population increased around the middle of the eighteenth century, however, people living within the small and crowded town of Charles Town witnessed the area’s first suburban expansion. In the spring of 1745, attorneys representing then-Commodore George Anson subdivided his “Bowling Green” tract into an orderly landscape of new streets and numerous residential lots called Ansonborough (see Episode No. 111).

The creation of Ansonborough—South Carolina’s first residential subdivision—soon aroused important questions about civic responsibilities. The suburban residents of Ansonborough enjoyed the benefits of new streets that connected to the existing public streetscape of urban Charles Town, for example, but they didn’t contribute to the tax base that funded the maintenance of the town. To address this conundrum, in the absence of any sort of municipal government at the time, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified a law in May 1750 to create a new board of commissioners to superintend the streets of urban Charles Town. This act empowered the street commissioners to raise a new and additional tax—which became known as the “town tax”—on all urban properties in Charles Town that abutted a public street, for the purpose of creating and maintaining those streets. As old streets were extended and new streets created after 1750, the owners of properties abutting the new streets became liable to pay the additional “town tax.”[5] As a result of this process, swaths of property formerly deemed to be outside the town were—for all practical purposes—annexed into the town of Charles Town in the years before the city was officially incorporated in 1783.

This process of tacit annexation was formalized, in a manner of speaking, by the creation of Boundary (now Calhoun) Street in the autumn of 1769. The residents of Ansonborough petitioned the General Assembly for a broad avenue to connect the northern edge of their neighborhood to the Broad Path (now part of King Street), which was the only road leading in and out of Charles Town at that time. By creating a new public street, seventy feet wide and stretching from King Street eastward to the Cooper River, the provincial government satisfied that request and simultaneously moved the town’s northeastern boundary several blocks to the north.[6] For the moment, however, the town’s original northwestern boundary—marked by modern Beaufain Street—remained unchanged.

This process of tacit annexation was formalized, in a manner of speaking, by the creation of Boundary (now Calhoun) Street in the autumn of 1769. The residents of Ansonborough petitioned the General Assembly for a broad avenue to connect the northern edge of their neighborhood to the Broad Path (now part of King Street), which was the only road leading in and out of Charles Town at that time. By creating a new public street, seventy feet wide and stretching from King Street eastward to the Cooper River, the provincial government satisfied that request and simultaneously moved the town’s northeastern boundary several blocks to the north.[6] For the moment, however, the town’s original northwestern boundary—marked by modern Beaufain Street—remained unchanged.

All of these details related to Ansonborough might seem like a diversion from the story of the Harleston neighborhood, but they’re important to this narrative because they established a precedent for subsequent developments adjacent to urban Charles Town. Following the death of Elizabeth Harleston in 1756, her three surviving sons, John (1708–1767), Nicholas (1710–1768), and Edward (1722–1775), jointly inherited the pasture containing approximately 130 acres on the northwest part of Charles Town.[7] In early November of 1767, the Harleston brothers submitted a petition to the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly that signaled the first steps towards the creation of a new suburban development.

The 1767 petition submitted by the Harleston brothers, “and others,” states that their lands “on the northwest part of Charles Town known by the name of Comings point,” had been “of late years included in the plan of Charles Town, and paid tax as part of the said town,” although “no Streets were laid out thro’ them.” The petitioners explained that they had recently “laid the said lands out into lots, and carried proper streets thro’ the same,” and even presented to the legislature a plan or illustration of the proposed subdivision. The Harleston brothers were unable to proceed with the subdivision of their property, however, because the land they called Coming’s Point was not contiguous to the principal thoroughfare leading into town, called the Broad Path (King Street). There were “other persons who own lots of land between your petitioners’ lands and the streets of Charles Town,” they explained, and so their plan faced “great inconveniences . . . for want of streets and thoroughways [sic] to and from their lands.” The Harlestons asked the legislature for help in bridging their neighbors’ private property with new public streets, which they believed “would be both useful and ornamental to this large and growing town and by no means detrimental to the owners of those lands thro’ which they shall be made.”[8]

The private property lying between the Harleston lands and the town included the seventeen acres Affra Coming had donated to the Parish of St. Philip in 1698, as well as the adjacent strip of approximately sixteen acres that John Coming had sold sometime prior to his death in 1695. The subdivision of Coming’s Point into a residential neighborhood could not proceed without carving a series of new streets through and across this swath of thirty-three acres on the west side of King Street, but that property had changed a lot since the 1690s. Around the year 1699, the vestry of the Anglican Church in urban Charles Town erected a parsonage house for its minister near the southern end of the glebe land donated by Affra Coming—somewhere near what is now the northwest corner of Beaufain and St. Philip Streets.[9] Then in 1712, an act of the provincial legislature ordered commissioners to erect and open a “Free School” on the northern edge of the glebe lands for the education of young white boys.[10] The Free School outgrew that building and moved into the heart of urban Charles Town in 1749, after which time the provincial government constructed a set of military barracks for one thousand men on the “Free School land” in the winter of 1757–58 and extended George Street westwardly from Ansonborough, across King Street, to the “new barracks” (as they were commonly called).[11] Between King Street and the parsonage, glebe, and barracks, stood a series of smaller lots owned a number of individuals, several of whom would have to sacrifice a bit of their real estate to facilitate the Harleston plan. In short, the Harleston family had to do a lot of negotiation with their neighbors.

The legislative committee assigned to review the Harleston petition of November 1767 did not report back to the Commons House until nearly four months later, in late February 1768, by which time two of the three petitioners, John Harleston and Nicholas Harleston, had died. Despite this setback, the members of the House committee reported that they believed the new streets proposed by the Harlestons would “be of use to the public in future time,” and recommended the creation of a bill for establishing the same according to the illustrated plan submitted earlier. As for the private property between Coming’s Point and King Street, the committee simply recommended that some “provision” be made “for granting an adequate compensation to the proprietors of those lands for any damage that they shall sustain” by the implementation of the Harleston plan.[12]

The legislative committee assigned to review the Harleston petition of November 1767 did not report back to the Commons House until nearly four months later, in late February 1768, by which time two of the three petitioners, John Harleston and Nicholas Harleston, had died. Despite this setback, the members of the House committee reported that they believed the new streets proposed by the Harlestons would “be of use to the public in future time,” and recommended the creation of a bill for establishing the same according to the illustrated plan submitted earlier. As for the private property between Coming’s Point and King Street, the committee simply recommended that some “provision” be made “for granting an adequate compensation to the proprietors of those lands for any damage that they shall sustain” by the implementation of the Harleston plan.[12]

The Commons House continued its discussion of the Harleston plan at the beginning of March, 1768, and then ordered the matter back to a committee for further work. In a series of debates continuing throughout that month, the members of the House considered the complex issues of extending various proposed streets through the glebe lands, around the new barracks, and through parcels of land belonging to obstinate owners. Abstracts of these discussions, which are found in the surviving manuscript journal of the Commons House, demonstrate that the now-familiar street names of the Harleston neighborhood were part of the original plan proposed in late 1767. Only one proposed street—identified in March 1768 as “Camden Street”—did not survive that legislative debate.

The most pressing question surrounding the proposed streetscape concerned money, of course. In a series of votes in March 1768 the Commons House resolved to make the Harleston developers pay all the expenses related to the surveying and laying out of the new streets, as well as compensating the owners of private lands diminished by the extension of new streets. There was just one exception to this rule: Beaufain Street, which formed both the southern boundary of the Harleston land and the northwestern boundary of Charles Town, was deemed sufficiently useful that the Commons House agreed to make the inhabitants of the town pay for that part of Beaufain Street extending from the eastern edge of the Harleston lands (that is, Coming Street), across the parsonage lands, all the way to King Street.[13]

The legislative debate of the Harleston development plan in the spring of 1768 resolved several necessary questions about its implementation, but the Commons House failed to draft a bill to authorize the plan before it adjourned for the summer on April 12th. The Assembly’s plan to pick up this and other matters in the fall was frustrated on September 8th, however, when South Carolina’s Lieutenant Governor, William Bull (in the absence of vacationing Governor Charles Greville Montagu), unexpectedly dissolved the General Assembly. New elections were held in October, and a new Commons House met in Charleston on November 15th. Four days later, Governor Montagu again dissolved the General Assembly to punish what he considered a disrespectful House.[14] Elections were again held in the spring of 1769, but the Commons House did not proceed to business until the end of June.

On August 8th, 1769, the Commons House read a new petition from “the owners and proprietors of the lands on the north west part of Charles Town, known by the name of Coming’s Point.” The authors of this petition were not identified in the surviving legislative records, but they probably included Edward Harleston, the last surviving son of John Harleston of Dublin, and his nephews. Beginning a fresh debate of the Harleston’s subdivision plan, the House committee assigned to review the petition revisited many of the same issues that had been resolved more than a year earlier and again recommended the creation of a bill to set the plan in motion. A few days later, however, the legislature adjourned for a brief recess and, once again, dropped the matter entirely.[15]

The Harleston family proprietors of the lands on the northwest side of Charles Town known as Coming’s Point submitted a third petition to the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly in January 1770, and again asked the legislature to assist them in overcoming the legal obstacles frustrating their development plan. This time, they noted one slight change. To resolve a difficulty with the owners of a piece of land situated between the glebe lands and King Street, one of the Harleston clan had purchased the land in question in order to complete the eastward extension of Montagu Street. That plan was apparently thwarted by other neighbors, however, so the family had resolved to terminate Montagu Street at its intersection with Coming Street. By this time, the vestry of St. Philip’s Parish had also realized that the creation of streets through the glebe land would permit them to subdivide that property into building lots that could be leased to generate revenue for the church. Furthermore, the creation of Beaufain Street through the old parsonage land provided the parish with an excuse to build a new and grander residence for the minister of St. Philip’s Church. With the various issues of compensation and street trajectories resolved, and with the church vestry on board, the Commons House finally drafted a bill to endorse the Harleston development scheme.[16]

The Harleston family proprietors of the lands on the northwest side of Charles Town known as Coming’s Point submitted a third petition to the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly in January 1770, and again asked the legislature to assist them in overcoming the legal obstacles frustrating their development plan. This time, they noted one slight change. To resolve a difficulty with the owners of a piece of land situated between the glebe lands and King Street, one of the Harleston clan had purchased the land in question in order to complete the eastward extension of Montagu Street. That plan was apparently thwarted by other neighbors, however, so the family had resolved to terminate Montagu Street at its intersection with Coming Street. By this time, the vestry of St. Philip’s Parish had also realized that the creation of streets through the glebe land would permit them to subdivide that property into building lots that could be leased to generate revenue for the church. Furthermore, the creation of Beaufain Street through the old parsonage land provided the parish with an excuse to build a new and grander residence for the minister of St. Philip’s Church. With the various issues of compensation and street trajectories resolved, and with the church vestry on board, the Commons House finally drafted a bill to endorse the Harleston development scheme.[16]

On April 7th, 1770, Governor Charles Greville Montagu gave his assent to the Harleston bill, which was ratified under the long title “An Act for laying out and establishing several new Streets in the North-west parts of Charles Town; and for building a new Parsonage House for the Parish of Saint Philip, Charlestown; and for empowering the Vestry and Church-Wardens of the said Parish, for the time being, to lay out part of the Glebe Land of the said Parish, in Lots, and to let the same out on Building leases; and for other purposes therein mentioned.”[17] The full text of the legislative act to create the Harleston subdivision has been available to the public for nearly two and a half centuries in various published formats, but the original engrossed manuscript of that law is kept in secure storage with the other statute laws of South Carolina at our state archive in Columbia.

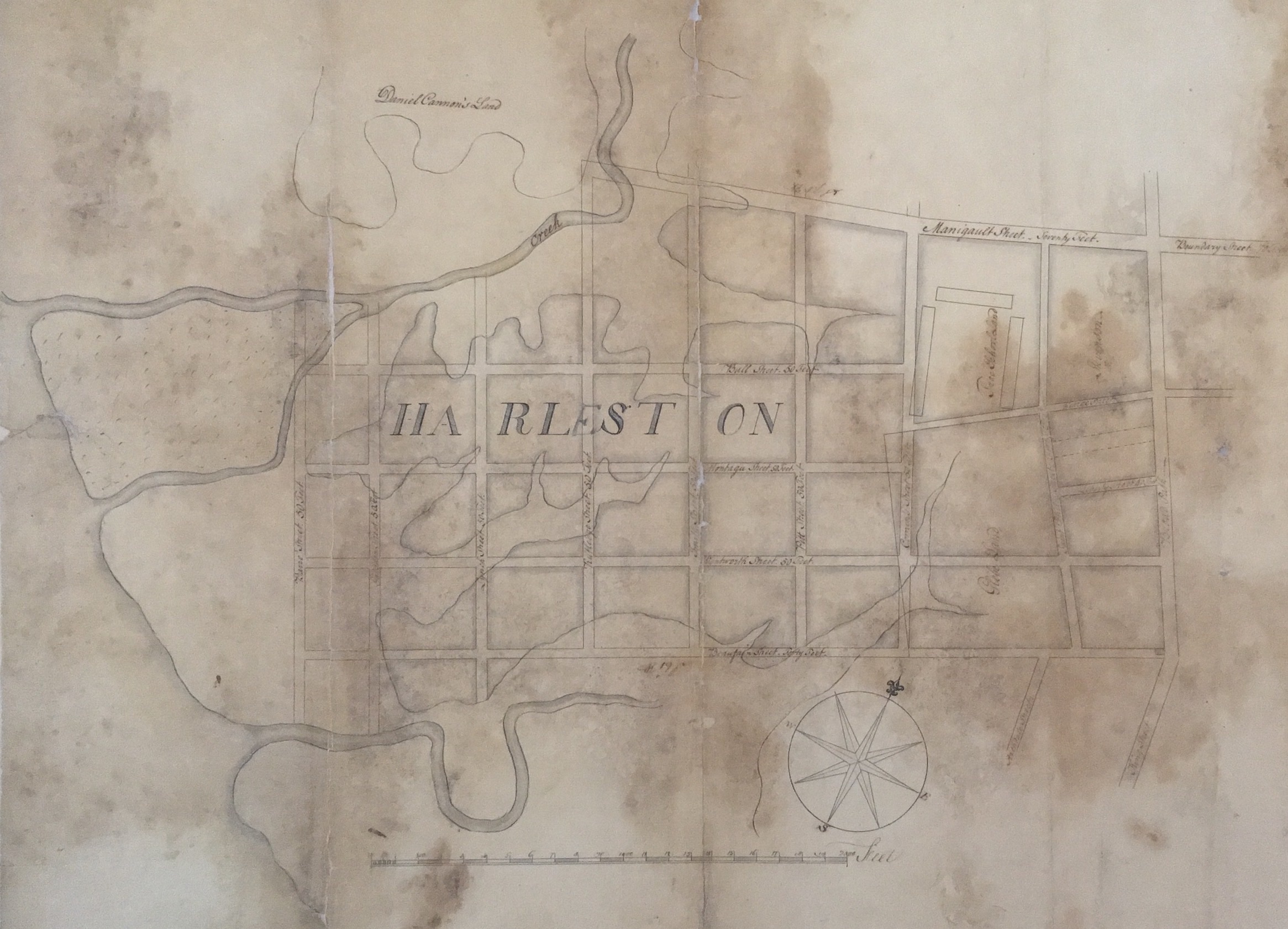

If you pay close attention to the text of the 1770 Harleston act, you’ll notice that it includes several references to a plat or plan of the neighborhood and its streets that was supposed to be annexed or attached to the original manuscript. That plat, executed by surveyor Rigby Naylor, is indeed still attached to the engrossed manuscript copy of the law, which I recently examined at the state archive (SCDAH). I don’t think this public document has ever been published, so I’m attaching a couple of amateur photos of it to this text. Naylor’s 1770 plat shows a large swath of land bounded on the east (right) by the “Broad path” (King Street) and on the west (left) by the Ashley River. That land includes the new subdivision, here styled “Harleston” in large capital letters, as well as the adjacent property that is separate and distinct from Harleston, including the “Free School land” on which the U-shaped barracks stand, the “Glebe Land” of St. Philip’s Parish, and the strip of private property between those features and King Street.

The Harleston brothers who submitted the original petition to subdivide their property in November 1767 also assigned names to the neighborhood’s twelve original streets. In selecting names for these thoroughfares, they simultaneously paid respect to the South Carolina’s incumbent political leaders and acknowledged the contributions of several men who had vocally opposed the controversial British tax law of 1765 known as the “Stamp Act,” which was repealed in 1766 to the great joy of American colonists.

Barre Street was named for Isaac Barré (1726–1802), the Irish-born son of French Huguenots who is credited with coining the phrase “Sons of Liberty” to describe American colonists during the Stamp Act Crisis of 1765–66. Beaufain Street was named for Hector Berringer de Beaufain (1697–1766), who served as Collector of Customs for the Port of Charles Town, 1742–66. Bull Street was named for South Carolina Lieutenant Governor William Bull Jr. (1710–1791). Coming Street was named for John and Affra Coming, who acquired this land in 1672. Gadsden Street was named for Christopher Gadsden (1724–1805), who represented South Carolina at the first intercolony Stamp Act Congress in New York in 1765. Lynch Street (later renamed Ashley Avenue) was named for Thomas Lynch (1727–1776), who also represented South Carolina at the Stamp Act Congress in New York in 1765. Manigault Street (which soon became the western half of Boundary [now Calhoun] Street) was named for Peter Manigault (1731–1773), who served as Speaker of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly in the late 1760s and early 1770s, and who owned the land on the northeast side of Harleston. Montagu Street was named for South Carolina Governor Charles Greville Montagu (1741–1784). Pitt Street was named for William Pitt “the elder” (1708–1778), the British Whig parliamentarian who spoke passionately for the rights of American colonists during the Stamp Act Crisis. Rutledge Street was named for John Rutledge (1739–1800), who also represented South Carolina at the Stamp Act Congress in New York in 1765. Smith Street was named for Benjamin Smith (1735–1790), who was married to Elizabeth Ann Harleston (daughter of Nicholas Harleston and Sarah Child), and who owned land on the northeast side of Harleston. Wentworth Street was named for British Whig politician Charles Watson-Wentworth, the Marquess of Rockingham (1730–1782), who became prime minister in July 1765 and introduced the legislation to repeal the Stamp Act in early 1766.

As you can see in the plat, the original subdivision of the Harleston family’s land was bounded on the east by Coming Street; on the south by Beaufain Street; on the north by Manigault Street (now part of Calhoun Street); and on the west by Barre Street and the Ashley River. Everything south of Beaufain Street (with the exception of a small patch of land at the southwest end of that street) was originally quite separate and distinct from the neighborhood of Harleston. Most Harlestonians today consider the area around Colonial Lake part of their neighborhood, but the land south of Beaufain Street and west of Smith Street, extending westward to the channel of the Ashley River, was once part of a government reservation designated as a public “common” for the inhabitants of Charles Town in 1768. After the incorporation of the City of Charleston in 1783, a succession of city leaders gradually sold off most of that public land until the remnants were re-branded “the Colonial Common and Colonial Lake” in 1881. We’ll talk more about that controversial topic in a future program.[18]

As you can see in the plat, the original subdivision of the Harleston family’s land was bounded on the east by Coming Street; on the south by Beaufain Street; on the north by Manigault Street (now part of Calhoun Street); and on the west by Barre Street and the Ashley River. Everything south of Beaufain Street (with the exception of a small patch of land at the southwest end of that street) was originally quite separate and distinct from the neighborhood of Harleston. Most Harlestonians today consider the area around Colonial Lake part of their neighborhood, but the land south of Beaufain Street and west of Smith Street, extending westward to the channel of the Ashley River, was once part of a government reservation designated as a public “common” for the inhabitants of Charles Town in 1768. After the incorporation of the City of Charleston in 1783, a succession of city leaders gradually sold off most of that public land until the remnants were re-branded “the Colonial Common and Colonial Lake” in 1881. We’ll talk more about that controversial topic in a future program.[18]

Similarly, the land immediately south of Beaufain Street, stretching between Logan Street on the east and Smith Street to the west, continuing southward to Broad Street, was part of a thirty-four-acre grant to James Moore in 1698. This land later became vested in the Mazyck family, who subdivided it in the mid-eighteenth century. That compact neighborhood, once bounded by the Ashley River at high tide, was used extensively as a burial ground by the British Army in the early 1780s, and afterwards by the City of Charleston. As a result of that long practice, the Mazyck lands later became the home to a less affluent class of residents. Many folks now consider this area part of the Harleston neighborhood, but it has a distinct history that we’ll explore in future episodes.

Following the ratification of the legislative act that endorsed the subdivision of Harleston, the family began marketing the availability of 162 half-acre lots for sale. Edward Harleston—the last surviving son of John Harleston of Dublin—promoted these sales with his nephew Isaac Harleston (1745–1798, son of John Harleston, 1708–1767), and nephew-in-law, Thomas Corbett (1749–1819, who was married to Margaret Harleston, daughter of John Harleston). The initial advertisement of these lots still described the neighborhood as “Coming’s Point, pleasantly situated between the Glebe Land of St. Philip’s Parish, and Ashley River, on which it has an extensive front, and commands an agreeable prospect of the adjacent plantations.” Twenty-first-century residents concerned about flooding might be amused to read the 1770 assertion that “the land is high and airy, and has the advantage of two good [boat] landings; one of which, Coming’s Creek, runs bluff to the high land, [and] will admit a loaded schooner of 100 barrels burthen.”[19]

In the years after the official debut of Harleston, most of the original 162 lots were repeatedly subdivided into smaller parcels and the landscape gradually filled with houses. The original name, Coming’s Point, quickly disappeared, however and “Harleston” prevailed.[20] After the American Revolution, in the late 1780s, when there were still few houses in the neighborhood, it was occasionally called “Harleston Green,” but that appellation faded as the land became more developed in the early nineteenth century. For most of its history, the neighborhood was known simply as Harleston. Today, however, nearly everyone calls it “Harleston Village,” which ruffles my historical feathers. Let’s review a few facts regarding this controversy as we head towards a conclusion.

The Harleston neighborhood was never an independent village, separate from the town of Charleston. Its developers stated in 1767 that they were already paying the “town tax” and sought to integrate more formally their private property with the town’s urban streetscape. The 1770 legislative act authorizing this merger noted that the Harleston land then formed the northwest part of Charles Town, and the neighborhood’s northern boundary, initially called Manigault Street, immediately thereafter became the westward continuation of Boundary Street (now Calhoun Street). When compared to a truly independent colonial village, like Hampstead Village of 1769 (which I recently profiled in Episode No. 131), you can see that Harleston is clearly a different sort of subdivision.

In my copious searching through the historic newspapers of early Charleston, I’ve encountered the phrase “village of Harleston” just a handful of times in advertisements dating from the early nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The phrase “Harleston Village,” on the other hand, very rarely appeared in print prior to the year 1970. In that year, an extension of the urban Charleston “historic district” recognized by the National Register of Historic Places annexed a place called “Harleston Village” under its protective umbrella. Local residents had advocated for this inclusion to foil a plan to extend a bridge from James Island to a site near the foot of Beaufain Street. Months later, the Harleston Village neighborhood association was formally organized, and the name has stuck ever since.[21]

In my copious searching through the historic newspapers of early Charleston, I’ve encountered the phrase “village of Harleston” just a handful of times in advertisements dating from the early nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The phrase “Harleston Village,” on the other hand, very rarely appeared in print prior to the year 1970. In that year, an extension of the urban Charleston “historic district” recognized by the National Register of Historic Places annexed a place called “Harleston Village” under its protective umbrella. Local residents had advocated for this inclusion to foil a plan to extend a bridge from James Island to a site near the foot of Beaufain Street. Months later, the Harleston Village neighborhood association was formally organized, and the name has stuck ever since.[21]

Whatever you call it, we can all agree that Harleston is a genuine historic neighborhood with plenty of character and charm. The current understanding of its boundaries now encompasses the old “Free School land” (now the College of Charleston) the old Glebe Lands, the Mazyck family land, and most of the Colonial Common, but I prefer to think of Harleston as a smaller rectangle with a colorful identity distinct from those of its immediate neighbors. We don’t need to invent stories and names to embellish Charleston’s historic appeal. We just need to dip into the well of surviving resources and revel in the complexity of the authentic and occasionally surprising facts.

[1] Henry A. M. Smith, “Charleston and Charleston Neck: The Original Grantees and the Settlements along the Ashley and Cooper Rivers,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 19 (January 1918): 8–10.

[2] Alexander S. Salley Jr., ed., Journals of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina For the Two Sessions of 1698 (Columbia: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1914), 32–33.

[3] Theodore D. Jervey, “The Harlestons,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 3 (July 1902): 150–73.

[4] South Carolina Gazette, 26 February–5 March 1750. The advertisement directed the public to contact Mrs. Harleston or Jonathan Scott for information about the land. Jervey, “Harleston Family,” 171, says Jonathan Scott married Ann Harleston (only daughter of John Harleston, the emigrant) in 1737.

[5] Act No. 775, “An Act for keeping the Streets in Charles Town clean, and establishing such other regulations for the security Health and Convenience of the Inhabitants of the said Town as are therein mentioned, and for establishing a new Market in the said Town,” ratified on 31 May 1750. This act was not included in the nineteenth-century collection of the Statutes at Large of South Carolina, but the engrossed copy of the law is found among the manuscript records of the General Assembly at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH). The provincial legislature refined and extended the responsibilities of the Commissioners of Streets in a series of statutes ratified between 1751 and 1775.

[6] Act No. 985, “An Act for laying out and establishing a public Street in Ansonburgh [sic], and the parts adjacent thereto,” ratified on 23 August 1769, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 92–93.

[7] The will of Elizabeth Harleston, dated 5 June 1754 and proved on 2 July 1756, is found in WPA transcription volume 7 (1752–56), pages 533–36.

[8] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, No. 37, part 2 (1767–68), pages 456–57 (4 November 1767).

[9] The construction date of the first parsonage is unknown, but it was definitely standing by 16 November 1700, when the South Carolina legislature passed “An Act for Securing the Provincial Library at Charles Town, in Carolina.” See McCord, ed., Statutes at Large, 7: 13–16.

[10] Frederick Dalcho, An Historical Account of the Protestant Episcopal Church in South Carolina (Charleston, S.C.: E. Thayer, 1820), 95–96.

[11] Governor James Glen announced the removal of the Free School to the Commons House on 19 May 1749; see J. H. Easterby, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, March 28, 1749–March 19, 1750 (Columbia: South Carolina Archives Department, 1962), 143. For the “new barracks” of 1757–58, see Jack P. Greene, “The South Carolina Quartering Dispute, 1757–1758,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 60 (October 1959): 193–204; Fitzhugh McMaster, Soldiers and Uniforms: South Carolina Military Affairs, 1670–1775 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1971), 57–59.

[12] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, No. 37, part 2 (1767–68), page 535 (26 February 1768).

[13] See SCDAH, Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, No. 37, part 2 (1767–68), pages 540 (1 March 1768), 567 (11 March), 589–90 (16 March), 613–14 (24 March), 616 (25 March).

[14] South Carolina and American General Gazette, 2–9 September 1768; South Carolina Gazette, 24 November 1768.

[15] See SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, No. 38, part 1 (1769), pages 126–27 (8 August 1769), 144–45 (14 August), 168–69 (17 August).

[16] See SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, No. 38, part 2 (1769–70), pages 227–28 (23 January 1770), 267–68 (16 February), 277–80 (22 February), 327–328 (16 March), 334 (20 March), 337–38 (21 March), 342 (23 March).

[17] McCord, ed., Statutes at Large, 7: 93–96.

[18] See “An Act to appoint and authorize Commissioners to cut a Canal from the upper end of Broad-street into Ashley river; and to reserve the vacant Marsh on each side of the said Canal, for the use of a common for Charlestown; and to empower the Commissioners of the Streets in Charlestown, to remove a certain nuisance in the street commonly called Allen’s-street,” ratified on 12 April 1768, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 87–90.

[19] South Carolina Gazette, 3 May 1770.

[20] The name “Coming’s Point” was also used to describe a point of land that once formed the northernmost point of Morris Island, located in the southeastern portion of Charleston harbor. That island appellation remained firm for many generations after the death of Captain John Coming, and the name of the neighborhood apparently deferred to the name of the harbor location.

[21] Charleston News and Courier, 2 October 1970, page 9B; Charleston News and Courier, 7 May 1971, page 4C.

PREVIOUS: The Historical Landscape of the New Baxter-Patrick James Island Library

NEXT: The Shady History of Protecting Lowcountry Trees

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments