Freedom Won and Lost: The Story of Catherine in Antebellum Charleston, Part 2

Processing Request

Processing Request

Our enslaved protagonist, Catherine, was cheated out of freedom by an unscrupulous master, but she boldly asserted her independence and found an attorney to lobby for her legal emancipation. While they petitioned courts and the state legislature for justice, Catherine’s predicament was confounded by unresponsive litigants and the shifting sands of statute law. Legal manumission remained elusive, but Catherine managed to gain a significant measure of freedom in her later years. The sparse details of her life illuminate a dramatic story of women’s rights, African-American history, and a bit of courtroom drama.

Let’s begin with a quick review of the first installment of this story. Catherine was an enslaved woman of African descent who contracted with her owner, Antoine Plumet, around the year 1812, to purchase her own freedom. After working outside his home for a period of months or years and paying her wages to her master, Catherine was defrauded by Monsieur Plumet, who apparently had no intention of manumitting her. Following Plumet’s death in the spring of 1816, Catherine considered herself to be freed from the bonds of slavery and began to live and work independently. Meanwhile, Charleston musician Louis DeVillers acted as the executor of Plumet’s estate for a period of approximately two years, superintending the remaining goods and chattel the deceased Frenchman had left to some unnamed heirs residing in France. One of those heirs, Pierre François Brisson, arrived in Charleston by the summer of 1818 and took possession of Plumet’s estate, both for himself and as attorney for other unnamed heirs still residing in France. At some point after his arrival in Charleston, Monsieur Brisson physically repossessed Catherine, whom he considered his lawful property. On the first day of August, 1818, Brisson sold Catherine to a French baker, Pierre Labaussay, who lived just outside Charleston’s city limits on upper King Street.[1]

Gaining A Legal Voice:

By the autumn of 1818, Catherine was living with a new family under the familiar bonds of slavery. The details of her movements and contacts over the ensuing months are lost, but she apparently discussed her situation with close friends and expressed her continued desire to be free. Through channels and conversations unknown, Catherine met Isaac Edward Holmes (1796–1867), the scion of an old and respectable Charleston family, who had recently graduated from Yale College and in 1818 passed the bar in the city of his birth. It is possible that Mr. Holmes learned of Catherine’s predicament through an informal network within the city’s legal community, a sort of pool of pro bono cases through which young lawyers might gain courtroom experience and advance their careers. Regardless of the long-lost particulars of how they met, Catherine and Isaac must have been in contact by the end of 1819. She recounted to the twenty-three-year-old attorney the story of her life with Ann and Peter Catonnet, and their tripartite agreement with the late Antoine Plumet to allow Catherine to purchase her freedom for $300. Mr. Holmes, though no abolitionist, concurred that Catherine had been ill-treated and defrauded. He agreed to take her case, but the young lawyer probably advised his enslaved client that the legal process of securing her freedom involved a number of steps that might take many months to accomplish.[2]

By the autumn of 1818, Catherine was living with a new family under the familiar bonds of slavery. The details of her movements and contacts over the ensuing months are lost, but she apparently discussed her situation with close friends and expressed her continued desire to be free. Through channels and conversations unknown, Catherine met Isaac Edward Holmes (1796–1867), the scion of an old and respectable Charleston family, who had recently graduated from Yale College and in 1818 passed the bar in the city of his birth. It is possible that Mr. Holmes learned of Catherine’s predicament through an informal network within the city’s legal community, a sort of pool of pro bono cases through which young lawyers might gain courtroom experience and advance their careers. Regardless of the long-lost particulars of how they met, Catherine and Isaac must have been in contact by the end of 1819. She recounted to the twenty-three-year-old attorney the story of her life with Ann and Peter Catonnet, and their tripartite agreement with the late Antoine Plumet to allow Catherine to purchase her freedom for $300. Mr. Holmes, though no abolitionist, concurred that Catherine had been ill-treated and defrauded. He agreed to take her case, but the young lawyer probably advised his enslaved client that the legal process of securing her freedom involved a number of steps that might take many months to accomplish.[2]

The first step was to establish a legal voice for Catherine. As an enslaved woman of African descent, she was legally invisible to the courts of antebellum South Carolina. Fortunately for her, the so-called “Negro Act” of 1740, which formed the foundation of South Carolina’s slave code until 1865, included a provision tailored for this situation. Any free person of color, or any enslaved person claiming his or her freedom, could select a white representative to apply to the local Court of Common Pleas on their behalf. The court was empowered to admit said white representative as a legal guardian to act on behalf of the person claiming to be free. Moreover, the law empowered the guardian to file suit “against any person who shall claim property in, or who shall be in possession of,” the person claiming his or her freedom. This clause might sound rather liberal in the general context of South Carolina’s rigid slave code, but the burden of proof was always on the person claiming his or her freedom. The law of 1740 dictated “that it shall be always presumed that every negro, Indian, mulatto and mustizo [mestizo], is a slave, unless the contrary can be made [to] appear.”[3]

Acting initially as Catherine’s informal ally, Isaac Holmes submitted a petition to the Court of Common Pleas for Charleston District at some point in 1819 or perhaps the early days of 1820. Following the course prescribed by the state’s slave code, the court acknowledged and affirmed Holmes to be Catherine’s legal guardian—not in a custodial sense, but simply as her legal representative in any court of law. The paper records documenting this appointment no longer survive, but Holmes’s subsequent representation of Catherine in other legal venues acknowledged that the Court of Common Pleas had empowered him to act on her behalf.

Suing for Catherine’s Freedom:

On Wednesday, February 16th, 1820, Isaac E. Holmes filed a bill of complaint against Pierre Brisson in the Court of Equity for Charleston District. The text of the bill does not survive, but it probably included an overview of the case and several supporting documents like affidavits to illustrate the details. A later summary described the case as “a suit for the recovery of the freedom of a female of color named Catharine [sic], who is held as a slave by the defendant [Brisson], as the agent & representative of foreigners residing in France, under the will of the late Mr. Plumet.” That brief description includes one word—“recovery”—that addresses a crucial and dramatic facet of this story. Holmes was not simply arguing for Catherine’s emancipation; he was asserting that she had already become free, by virtue of her verbal contract with Antoine Plumet and by his subsequent death in 1816. The plaintiff argued that Pierre Brisson’s claim to hold Catherine as a slave was a violation of her civil liberties, and Holmes therefore sought the “recovery” of her legal freedom.

On Wednesday, February 16th, 1820, Isaac E. Holmes filed a bill of complaint against Pierre Brisson in the Court of Equity for Charleston District. The text of the bill does not survive, but it probably included an overview of the case and several supporting documents like affidavits to illustrate the details. A later summary described the case as “a suit for the recovery of the freedom of a female of color named Catharine [sic], who is held as a slave by the defendant [Brisson], as the agent & representative of foreigners residing in France, under the will of the late Mr. Plumet.” That brief description includes one word—“recovery”—that addresses a crucial and dramatic facet of this story. Holmes was not simply arguing for Catherine’s emancipation; he was asserting that she had already become free, by virtue of her verbal contract with Antoine Plumet and by his subsequent death in 1816. The plaintiff argued that Pierre Brisson’s claim to hold Catherine as a slave was a violation of her civil liberties, and Holmes therefore sought the “recovery” of her legal freedom.

In response to the filing of Holmes’s bill, the court would have issued a writ summoning the defendant, Pierre Brisson, to file his own bill in answer. From that moment, Catherine might have enjoyed a period of relative safety. She was now the ward of a guardian who had filed suit on her behalf, and the law temporarily shielded her from recriminations. The same 1740 law that empowered her guardian, Holmes, to sue for her freedom included a clause protecting the plaintiff’s ward from being “eloined [carried away], abused or misused.” If Brisson, or perhaps her new owner, Pierre Labuassay, sought to remove Catherine from the court’s jurisdiction or to intimidate her into submission, the court could prosecute them for contempt and possible criminal charges.[4]

Chancellor Thomas Waties opened the regular semi-annual session of the Charleston Court of Equity on Monday, February 21st, but Catherine’s case did not receive an immediate hearing. The court’s three-week session concluded in mid-March 1820, without receiving a response from Pierre Brisson. Following its normal calendar, the Charleston District Court of Equity convened again on Monday, November 13th, under Chancellor Theodore Gaillard, and continued for two weeks. Again, defendant Brisson did not file a response to the bill filed eight months earlier by Isaac Holmes. The reasons behind Brisson’s silence are not addressed in any surviving documents. Perhaps he felt that the suit had been wrongly filed against him, since he had sold Catherine to Pierre Labaussay in 1818. Perhaps Brisson, as a recently-arrived French national, did not understand the American legal system and chose to ignore the court summons. Whatever the reasons behind the delay, Brisson’s inaction created serious complications for Catherine.[5]

The Legal Door Narrows:

Whether Pierre Brisson’s failure to respond to the Court of Equity was motivated by malice or greed or plain lethargy, he probably had no idea of the damage his inaction would inflict on Catherine’s case. If he had filed a timely response to Isaac Holmes’s suit in February or November 1820, the court would most likely have ruled in Catherine’s favor, and ordered her to be freed immediately. The suit initiated by her guardian, Holmes, would stand as a precedent to defeat any future challenges to her freedom, and she would have lived out her years in peace. While the months passed and Brisson did not respond, however, South Carolina’s elected lawmakers were voicing their contempt for the state’s growing population of free people of color. The narrow legal pathway from slavery to freedom, which the legislature had nearly closed in December 1800, was about to slam shut.

On December 20th, 1820, the South Carolina General Assembly in Columbia ratified an act specifically designed to prevent people like Catherine from becoming free. On that date, the state’s white male authorities proclaimed that “the great and rapid increase of free negroes and mulattoes [sic] in this State, by migration and emancipation, renders it expedient and necessary for the Legislature to restrain the emancipation of slaves, and to prevent free persons of color from entering into this State.” To remedy this situation, the state plainly decreed “that no slave shall hereafter be emancipated but by act of the legislature.” With this brief phrase, the General Assembly closed all customary pathways that heretofore had permitted many hundreds of enslaved South Carolinians to become free. To gain freedom from slavery, an individual now had to obtain the legislative consent of the majority of the state’s most conservate white slaveholders.[6]

News of the legislative proceedings in Columbia appeared in Charleston’s daily newspapers throughout the month of December 1820, but it’s unclear how Catherine learned of the new prohibitive law. Perhaps she heard others speak of it on the streets and ran to the office of Isaac Holmes in search of an explanation. The young attorney might have explained to her that the act “to restrain the emancipation of slaves,” while injurious to her case, did not obliterate her chances of regaining her freedom. The Court of Equity, in which they had sought to defeat the claim of Pierre Brisson, now lacked the power to render a final decision on that matter, but a good showing in that venue would strengthen their case in the next forum. Soon they would appeal to the state legislature and try to convince the gentlemen of the House of Representatives and the Senate to ratify an act to restore Catherine’s freedom. For the moment, however, they still needed to focus on case before the Court of Equity. Hope was not yet lost.

Catherine’s Day in Court:

On Thursday, February 15th, 1821, Pierre François Brisson finally submitted a bill to the Court of Equity, in answer to that filed by Isaac Holmes fifty-two weeks earlier. Chancellor Henry W. DeSaussure opened the semi-annual session on Monday, February 19th, within the Charleston District Courthouse at the northwest corner of Meeting and Broad Streets, and continued daily until the middle of March. Although the precise date of Catherine’s hearing is unclear, at some point during that three week period, the bailiff called forward the parties involved in “Holmes, Guardian of Catharine [sic] Vs. Pierre F. Brisson.”[7]

On Thursday, February 15th, 1821, Pierre François Brisson finally submitted a bill to the Court of Equity, in answer to that filed by Isaac Holmes fifty-two weeks earlier. Chancellor Henry W. DeSaussure opened the semi-annual session on Monday, February 19th, within the Charleston District Courthouse at the northwest corner of Meeting and Broad Streets, and continued daily until the middle of March. Although the precise date of Catherine’s hearing is unclear, at some point during that three week period, the bailiff called forward the parties involved in “Holmes, Guardian of Catharine [sic] Vs. Pierre F. Brisson.”[7]

The court did not record a transcript of the arguments, and the bills submitted by both the plaintiff and defendant are now lost. It seems likely that Isaac Holmes might have argued his own case before the court, but the identity of Brisson’s attorney is unknown. The plaintiff presented a summary of Catherine’s life over the preceding decade, and his arguments were supported by witnesses like Ann and Peter Catonnet, who testified in regard to their bargain with Antoine Plumet to permit Catherine to purchase her own freedom for $300. For his defense, Pierre Brisson simply argued ignorance of the entire matter. He had come to Charleston to take possession of property inherited from the late Antoine Plumet, and he knew nothing about a verbal contract between Plumet, the Catonnets, or Catherine.

Unlike the more familiar civil court, in which judges render decisions based strictly on the application of prior case law and precedent, judges in Equity Court use their professional experience and discretion to weigh the evidence at hand and determine the most equitable and fair resolution for the parties involved. Although most of the documentation related to Catherine’s 1821 case is now lost, we are fortunate that the final decree written by Judge Henry W. DeSaussure survives.

“Holmes, Guardian of Catharine Vs. Pierre F. Brisson

This is a suit for the recovery of the Freedom of a female of color named Catharine, who is held as a slave by the defendant, as the agent & representative of foreigners residing in France, under the will of the late Mr. Plumet.

It was proved that Catonet owned the person in question, & agreed to sell her to Plumet for $300, on condition, that whenever she repaid him the money he paid for her, she should have her freedom. It was also proved that she was very faithful, & of great value, not less than $800; and that the inducement to Catonet to take so low a price as $300 was the condition that she should have her freedom on repaying the sum paid by Plumet for her. It was further proved that Plumet acknowledged that the woman Catharine had repaid him the $300 some years before his death: but he still retained her in servitude, alledgeing that she must also pay interest on the price. The witness proves also that he had retained her in servitude long enough to have repaid by her labor much more than the interest.

Plumet did not set her free before his death according to his contract with Catonet. By his last will he bequeathed his property to certain relations in France whom the defendant represents. The executor of Plumet [Louis DeVillers] has received some wages for her since the death of his testator, but not much, as she claimed her freedom. The woman was proved to be of good character, healthy & capable of maintaining herself. The question is, can she recover her freedom under these circumstances, according to our laws?

By our statute of the year 1800 the mode of emancipating slaves is prescribed, & it is enacted that all other modes of attempted emancipation should be void. This statute I consider imperative & conclusive on the case, and this renders it unnecessary to examine all the doctrines gone into by the counsel. There can be no equitable mode of emancipation, different from & in violation of the statute. The case of Bennet decided in this Court, the case of Exors. [of] Walker vs. Bostick reported in 4 Equity Reports 266, & the case of Mathis & Salmon recently decided at Columbia & not reported, all shew how strictly the Court feels itself bound by the statute.

We may censure Plumet for not performing his contract with Catonet. We may even consider him as guilty of a fraud on that contract, for which it is possible Catonet might have a remedy though I do not express any opinion on that point which is not before me, Catonet not being a party to this suit, but still the question recurs. Can a Court acting on rules of law decide that this person is entitled to her freedom, when she has not been emancipated according to law? Or can the Court decree that the parties, foreigners residing abroad, should carry the contract made by Plumet with Catonet into specific execution, and emancipate her in the legal forms? I apprehend that the Court cannot. And so thought the Federal Circuit Court in the Case of Annette under nearly similar circumstances.

Indeed a subsequent law of December 1820 has made it more difficult, for it has enacted that no emancipation shall be valid but by petition to the Legislature & a special law authorizing it in every case. The Legislature might possibly listen to the application in such a case, where the purchaser had violated the condition of his contract made with the former owner for the benefit of the slave and gained a great benefit by such condition & by the violation of it. I am not sure that it would erect itself into a tribunal to try a disputed claim to freedom, as of right. Be that as it may, it is not for the Court to advise or direct. It is our painful duty often to witness cases of hardship, almost beyond the reach of human redress—and I should feel this as one of extreme hardship on the female Catharine, unless experience had shewn that the gift of freedom to one who must still remain in a degraded class, is not always a blessing but more frequently a curse.

The Bill must therefore be dismissed, but without costs, as the respectable person who instituted the suit as Guardian acted from the purest humanity in a case of real hardship.

Henry W. DeSaussure.”[8]

Appealing to the Legislature:

In the wake of the inconclusive decree rendered by the Court of Equity in March 1821, Catherine and her guardian, Isaac Holmes, turned their attention to the most obvious next step. As Judge DeSaussure had hinted in his decree, the plaintiffs would have to address a petition to the state legislature, which now formed the final arbiter in all cases of future emancipation in South Carolina. The state General Assembly was, at that time, in the habit of convening each year in late November and concluding business before the end of December. The details of Catherine’s life between March and November 1821 are now lost, but she probably continued living with the family of Pierre Labaussay on upper King Street and sharing the wages she earned with her legal owners. At some point in November, Isaac Holmes drafted two copies of a long petition, comprising several sheets of paper, and sent one each to the South Carolina Senate and to the House of Representatives. Only the Senate copy of Holmes’s four-page petition survives, and the South Carolina Department of Archives and History has digitized the entire document and placed it online.

In the wake of the inconclusive decree rendered by the Court of Equity in March 1821, Catherine and her guardian, Isaac Holmes, turned their attention to the most obvious next step. As Judge DeSaussure had hinted in his decree, the plaintiffs would have to address a petition to the state legislature, which now formed the final arbiter in all cases of future emancipation in South Carolina. The state General Assembly was, at that time, in the habit of convening each year in late November and concluding business before the end of December. The details of Catherine’s life between March and November 1821 are now lost, but she probably continued living with the family of Pierre Labaussay on upper King Street and sharing the wages she earned with her legal owners. At some point in November, Isaac Holmes drafted two copies of a long petition, comprising several sheets of paper, and sent one each to the South Carolina Senate and to the House of Representatives. Only the Senate copy of Holmes’s four-page petition survives, and the South Carolina Department of Archives and History has digitized the entire document and placed it online.

Through carelessness or confusion, Isaac Holmes’s 1821 petition misidentified Catherine’s former owner, Antoine Plumet, by referring to him as “Dr. Plumeau.” It seems that Mr. Holmes conflated the similar names of three different Frenchmen in his petition. As I mentioned in the previous program, one Dr. John Plumet resided in Charleston at the beginning of the nineteenth century. His relative and Catherine’s legal owner, Antoine Plumet, died in 1816. Mr. Holmes confused these two deceased Frenchmen with a fellow refugee from Saint-Domingue then living in Charleston, named John Francis Plumeau (1786–1847). Monsieur Plumeau was not a doctor and had nothing to do with Catherine’s predicament, however, so we must excuse Mr. Holmes’s slip of the pen and focus on the facts of case at hand.[9]

To the Honble. the President and Members of the Senate.

The respectful memorial of I. E. Holmes,

Sheweth, That he was appointed by the Court of Common Pleas, Guardian of a Negro wench, named Catherine who claims her freedom. A bill was filed in the Court of Equity for Charleston in the So. circuit, Feby 16th 1820, which bill sets forth that the wench Catherine was the property of Peter Catonet, merchant of Charleston, and that the said wench was purchased from said Catonet, by Dr. Plumeau, with the avowed object of enabling the wench to purchase her freedom. The wench was a valuable and favorite serv[an]t of Mr. Catonets, and he sold her for the sum of 300 Dlls. to Dr. Plumeau (a sum far below her value) for the purpose of conferring on the wench a benefit, and enabling the said Dr. Plumeau to carry into effect his charitable intention. A contract was then entered into between Dr. Plumeau and the wench Catherine, in presence of Mr. Catonet and his wife. That the wench Catherine sh[oul]d pay to Dr. Plumeau (300) Dlls. the am[oun]t of purchase money p[ai]d by Dr. Plumeau to Catonet and that when the s[ai]d sum sh[oul]d be paid by Catherine to Dr. Plumeau[,] Dr. Plumeau would execute papers, emancipating the said woman Catherine.

Dr. Plumeau is since dead, and the legatees have taken possession of the wench Catherine under the will of said Dr. Plumeau. The bill further states that the wench Catherine paid to Dr. Plumeau before his death, 300 Dlls., the sum agreed on as the price of emancipation. The answer to this bill was filed Feby. 15, 1821, denying any knowledge of the transaction, and stating that the owner or person claiming said wench, is a native of France, and possesses no knowledge of the contract entered into between Dr. Plumeau and the woman Catherine.

Two witnesses were examined before the Honble. Court of Equity, who proved that Dr. Plumeau was capable of so despicable a transaction as defrauding this Negroe of her rights. Nay, it was proved he had been in the habit of inducing masters of slaves to sell them for a less[er] price than the[ir] value, under pretense of emancipating them, and then defrauding the slaves themselves.

Mr. Catonet proved the agreement between the parties and also that the wench was sold at a price far below her value, which would not have been the case, if the fullest reliance had not been placed on the promise of Dr. Plumeau to emancipate the wench whenever the wench sh[oul]d pay to Dr. Plumeau 300 Dlls. It was further proved that the wench had been working out and carrying in wages, for a period sufficiently long to have paid double the sum.

Mrs. Catonet also proved, that Dr. Plumeau had confessed to her that the wench Catherine had paid to him the sum of 300 Dlls., but remarked that he was entitled to interest on that sum. It was then proved by the executor [of] Dr. Plumeau that the interest had been paid. On the argument it was contended that the doctrines relative to slaves were drawn from the civil law, and that the civil law must govern the case, so far as the Act of Assembly [of 1820] did not affect it.

That by the civil law, a slave could not contract because he might affect the rights of his master, but when this reason failed he c[oul]d contract, namely, he could contract with the leave and by permission of his master (authorities were produced in support of this position). Therefore a slave could contract with his master who gave him leave to do so, several cases were produced to show that this had actually happened.

The judges of the Appeal Court of Equity then delivered, deciding the case, and recommended a petition to the state legislature as by a late law [of 1820] they were constituted the proper tribunal to decide upon cases of this nature, stating at the same time that they would cheerfully give all the information to that honorable body, respecting the facts as they came out in evidence before the Court of Equity.

Your memorialist therefore prays your honorable House to pass an act, whereby the s[ai]d wench Catherine may be emancipated, and enjoy all the rights and privileges of a free Negroe in the State of South Carolina.

I. E. Holmes, Guardian of Catherine.”[10]

The Legislature, Inaction:

Holmes’s appeal on behalf of Catherine was one of twenty-two similar petitions submitted to the South Carolina General Assembly in November 1821 asking for permission to emancipate dozens of enslaved people. Both the South Carolina Senate and House of Representatives read Holmes’s petition on November 27th, at which time each chamber referred the petition to their respective committees charged with considering the other similar requests. The Senate committee reported on December 4th by presenting “A Bill to set free the slaves therein mentioned,” which received its first reading. The committee of the House of Representatives followed on December 7th with its own bill, which received a first reading that same day. It wasn’t until December 10th that the House heard the report of the committee that drafted the bill in question, however. The text of their report, which is found in the manuscript journal of the House session of 1821, provides valuable insight into the strange logic of institutional slavery in antebellum South Carolina.[11]

Holmes’s appeal on behalf of Catherine was one of twenty-two similar petitions submitted to the South Carolina General Assembly in November 1821 asking for permission to emancipate dozens of enslaved people. Both the South Carolina Senate and House of Representatives read Holmes’s petition on November 27th, at which time each chamber referred the petition to their respective committees charged with considering the other similar requests. The Senate committee reported on December 4th by presenting “A Bill to set free the slaves therein mentioned,” which received its first reading. The committee of the House of Representatives followed on December 7th with its own bill, which received a first reading that same day. It wasn’t until December 10th that the House heard the report of the committee that drafted the bill in question, however. The text of their report, which is found in the manuscript journal of the House session of 1821, provides valuable insight into the strange logic of institutional slavery in antebellum South Carolina.[11]

In their report, the House committee divided the twenty-two petitions for manumission into four categories. The first included requests predicated on a simple wish to reward certain faithful slaves, which the committee rejected without further consideration. The second category included white men who wished to free their mulatto children and their enslaved mothers. To remedy this practice, which legislators described as “an intercourse repugnant to morality and the best interests of society,” the committee recommended the fathers simply send their children out of state to find more congenial conditions elsewhere. The third category included petitions from seventeen executors who sought to manumit various people in accordance with the wills of deceased testators. The committee rejected their pleas as well, stating that the desired object was contrary to the state acts of 1800 and 1820, which rendered their requests “illegal and void.”

The fourth and final category included five petitions to manumit slaves who had contracted for their freedom with their respective owners, but, owing to a variety of “peculiar circumstances,” the necessary paperwork to effect their manumission was not executed before the ratification of the prohibitive act of December 1820. In contrast to the previous categories, the House committee opined that the five petitions in question, including that filed by Isaac Holmes on behalf of Catherine, “should receive the favourable consideration of the Legislature.” “These cases seem to form an exception to the prohibition of the law,” wrote the committee, “as the slaves in justice ought to have been manumitted previous to the last session [of the legislature, in December 1820]. Their number is so small that their emancipation will add but little to the evil apprehended from an increase of free persons of colour and as they are confined entirely to contracts made and executed before the act of 1820, their number cannot in future increase.”[12]

The House then read a second time the committee’s “Bill to emancipate certain slaves therein named,” and ordered it to be sent to the Senate for their consideration. The Senate received and read the House bill on December 11th without debate. The text of the bill does not survive, but the Senate journal of December 12th, 1821, includes a brief debate on a single provision in the bill. The proposed legislation apparently included a clause requiring the people soon-to-be-emancipated to leave South Carolina and never return. Senators were evenly divided over the penalties to be inflicted on such an emancipated person who might return to the state—should their former masters then forfeit a bond ensuring their departure, or should the freed person “be again reduced to slavery”? The Senate postponed further debate over this sticking point from December 12th, to the 13th, to the 14th, on which day the Senators “ordered that the Bill be postponed until the first Monday of January next.”[13]

But the South Carolina legislature did not convene in January 1822, and so the matter was—in theory, at least—laid over until the commencement of the next legislative session in November 1822. Unfortunately for Catherine and her pursuit of freedom, however, the events that unfolded in Charleston during the intervening summer dashed her chances of success. The city and the state of South Carolina in general were shocked in June 1822 by the discovery of a purported plot for slaves and free persons of color to launch a violent revolt against the white population. During a series of interrogations and trials held in June and July, white authorities extracted details of the plan from dozens of black suspects, and identified a free man named Denmark Vesey as the purported ringleader. Vesey and thirty-four other men were hanged in Charleston, and state authorities banished a further thirty-one men from the boundaries of South Carolina.[14]

The state acts of 1800 and 1820, which reduced and then closed the legal pathways from slavery to freedom, were the product of white concerns over the growing population of free persons of color. The trials and executions in the summer of 1822 amplified those fears to a fever of paranoia both in Charleston and at the state capital. When South Carolina legislators convened in Columbia in November 1822, the recent Denmark Vesey affair dominated their discussions and actions. The members of the state House of Representatives and Senate were in no mood to increase the population of free people of color whom they viewed with such distrust. When petitions came before them to emancipate various slaves, they simply rejected them and moved on to other business.[15]

Catherine’s Later Life:

Following the state legislature’s inaction on this case in December 1821, and their rejection of future emancipation in December 1822, Catherine must have realized that she would never legally regain her freedom in South Carolina. Isaac Holmes, her erstwhile guardian, might have sympathized with her defeat, but his promising legal career was just beginning to flower. Soon he would be elected to city, state, and national offices, and travel to distant lands in pursuit of his own destiny. At home in Charleston, however, the story of Catherine’s life quickly faded into obscurity. The paper trail outlining the rest of her life becomes increasing sketchy after 1822, making it difficult to draw definite conclusions about the remainder of her life. Despite the paucity of data, there is some evidence that Catherine might have enjoyed a modicum of freedom during her final years.

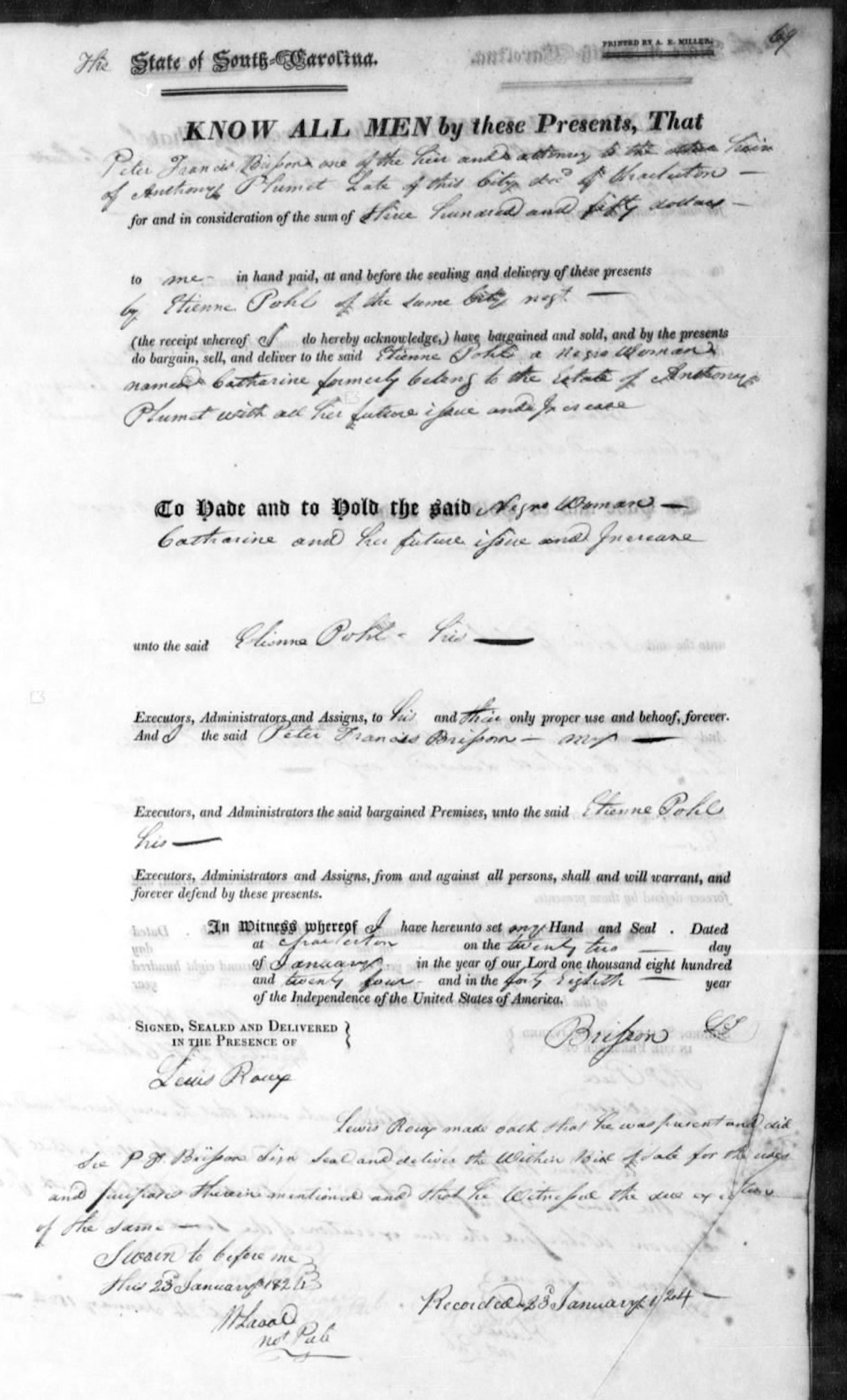

As I mentioned in last week’s program, Pierre Brisson ended Catherine’s brief life of freedom in 1818 and sold her that August to a French baker named Pierre Labaussay for $650. On September 23rd, 1823, Labaussay sold her back to Brisson for the same price, at which time she was again described as “a negro woman named Catherine (formerly belong[in]g to the estate of Anthony Plumet).”[16] The reasons behind this re-sale to Brisson are unclear, but it appears that Monsieur Labuassay, a native of Saintonge, France, was in declining health and might have needed to liquidate some of his assets. He made his will in December 1823, leaving all of his modest estate to his wife, Marie Catherine Labaussay, and died in the spring of 1824.[17]

As I mentioned in last week’s program, Pierre Brisson ended Catherine’s brief life of freedom in 1818 and sold her that August to a French baker named Pierre Labaussay for $650. On September 23rd, 1823, Labaussay sold her back to Brisson for the same price, at which time she was again described as “a negro woman named Catherine (formerly belong[in]g to the estate of Anthony Plumet).”[16] The reasons behind this re-sale to Brisson are unclear, but it appears that Monsieur Labuassay, a native of Saintonge, France, was in declining health and might have needed to liquidate some of his assets. He made his will in December 1823, leaving all of his modest estate to his wife, Marie Catherine Labaussay, and died in the spring of 1824.[17]

Four months after re-purchasing Catherine, Pierre Brisson sold her again on January 22nd, 1824, to another Frenchman in urban Charleston. For the now reduced sum of $350, Brisson conveyed to Etienne Pohl “a negro woman named Catherine formerly belong[ing] to the estate of Anthony Plumet.”[18] Forty-nine weeks later, on 2 January 1825, Pohl re-sold to Brisson the same woman for the same sum of $350.[19] Then on August 17th, 1825, Brisson sold Catherine again, now for $450, to Marie Catherine Coürsal Labaussay, the widow of Pierre, the baker.[20] At that time she was again described as “a negro woman named Catherine formerly belong[ing] to the estate [of] Anthony Plumet.” The reasons behind these various sales are unknown, so we have to use our imaginations to ponder why ownership of Catherine passed from hand to hand during the 1820s. Perhaps the pain of gaining and then losing her freedom broke her spirit and transformed her into a difficult person and unpleasant company. Perhaps Catherine simply expressed a desire to live with another family.

On April 14th, 1831, Catherine’s owner, Marie Labuassay, a native of Saint Domingue, made her last will and testament on the same day she became an American citizen. She owned at least a dozen slaves at that time, and directed her future executors to emancipate eight of her favorite people as soon as the state legislature amended the 1820 law prohibiting private manumission. The remaining slaves in the household, said Mrs. Labaussay, were to have “the privilege of choosing their owners & to be sold at a reasonable price.”[21] The enslaved woman Catherine, formerly the property of Antoine Plumet, was not among the eight favorite people named by Marie Labuassay who should be manumitted. Nor does Catherine appear among the eleven slaves named in the inventory of Madame Labaussay’s estate, which was appraised after her death in early June 1836.[22] Sometime between 1825 and 1836, Catherine disappeared from my historical radar.

In my effort to narrate Catherine’s story, I’ve explored a large number of records held at archives in both Charleston and Columbia. I was determined to find some document to illuminate her final years, so I considered the possibilities. Perhaps she ran away and found freedom elsewhere in a community opposed to the practice of slavery. Perhaps Madame Labaussay sold Catherine to another party and failed to record the transaction with the proper authorities. Or perhaps the baker’s widow grew tired of Catherine’s presence in her household and complained to Pierre Brisson, from whom she had purchased the enslaved woman in 1825. We might never know the truth of the matter, but I followed my hunch that Catherine might have returned to the possession of the man who spoiled her freedom.

Pierre François Brisson, a “native of Brossac in the arrondissement of Barbezieux in France,” but now residing on Wolfe Street on Charleston Neck, wrote his last will and testament in the spring of 1843. He bequeathed the bulk of his modest estate to cousins in France and directed his executors, Thomas W. Malone and Robert de Leaumont, to sell the rest. But Brisson also articulated two small exceptions. Two of the three enslaved women in his household were not to be sold. First, he gave his God-daughter, Cecilie Massallon, an enslaved woman named Lucy. Second, he addressed an old and faithful servant who I believe is our protagonist, Catherine. Brisson wrote “I give and bequeath to my executors aforenamed my slave Catherine in trust, for their use and behoof upon this condition[,] that they shall not & do not exact from her more than the annual wages of fifty five cents in consideration of her uncommon faithful services to me.”[23]

If the woman named Catherine in the will of Pierre Brisson is indeed our protagonist, then we can draw two important conclusions about the final years of her life. First, she seems to have been regarded as a faithful and congenial person, not a curmudgeonly old woman embittered by the loss of her freedom. Second, by specifying that Catherine would, for the foreseeable future, pay no more than fifty-five cents per year in wages to the executors of his estate, Brisson provided a valuable snapshot of her legal condition. Catherine had become what might call a “nominal slave,” a person who lived a relatively independent life but remained the legal property of another person. Her owner, Pierre Brisson, apparently allowed her to live and work as she pleased, only requiring her to render to him a small annual payment. It’s possible that Catherine had lived as a nominal slave since 1820, when Isaac Holmes pursued her freedom in Equity Court and then in the state legislature. The details of Catherine’s relationships with her various owners, including Mr. and Mrs. Labaussay, Etienne Pohl, and Pierre Brisson, are long lost, but they might have been more agreeable than oppressive. After the death of Monsieur Brisson, his executors were to perpetuate Catherine’s strange legal identity, holding her “in trust” for the protection and indefinite continuation of her status as a slave in name only.

Pierre Brisson died in late February 1844, but the precise date is now lost. In early March, Thomas W. Malone (1799–1864), an English-born attorney, qualified as the executor of Brisson’s estate and prepared an inventory of his belongings. In addition to various household goods, the estate included “one old diseased woman Catherine,” aged upwards of “60 years,” who was valued at just $5. In contrast, the other remaining slave, described as an “old negro woman named Dinah,” was valued at $100. Executor Malone advertised to sell Dinah and other household goods later in March 1844, but he probably followed Brisson’s instructions and allowed Catherine to continue living a relatively independent life.[24] Mr. Malone, a bachelor who formerly resided in New Orleans and shared his house in Charleston with a large number of black and mulatto women, apparently scoffed at the social conventions of his slave-holding neighbors. Facilitating Catherine’s freedom was certainly no bother to him.[25]

I have yet to find a conclusive ending to the story of Catherine’s life, but she probably died before the practice of slavery ended in Charleston in the spring of 1865. Although the date of her death is presently unknown, we can look back at the outline of her dramatic story and appreciate the few surviving facts of her existence. Catherine was a real person who lived and loved in the City of Charleston, and who probably cried a river of tears over the course of her difficult lifetime. My attempt to narrate a portion of her life has relied on the existence of a handful of records generated by contemporaries who either sought to oppress her or to help her. With a bit of attention to detail and context, it’s possible to re-animate her story, which might succeed as a screenplay or novel with sufficient imagination. But our state and local archives are full of other documents telling many rich stories, and I encourage everyone to roll up their sleeves and explore our community’s colorful history.[26]

[1] Brisson also sold other slaves belonging to Antoine Plumet, including William (son of Nolette), Rosalie, and Félicité with her infant daughter. See South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Miscellaneous Records (Main Series), Bills of Sale, 4S: 16 (19 March 1819); 4V: 327 (20 December 1820); 4V: 35 (18 January 1821).

[2] Isaac Edward Holmes was the son of John Bee Holmes (1760–1827) and Elizabeth Edwards. After graduating from Yale in 1815, he studied law under James Gadsden (1787–1831) during 1815–18, served as a warden on Charleston’s City Council, 1826–29, in the South Carolina House of Representatives, 1826–33, and then in the U.S. House of Representatives, 1838–50. See Alexander Moore, ed., Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives, volume 5 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1992), 128–30.

[3] See section 1 of Act No. 670, “An Act for the better Ordering and Governing Negroes and other Slaves in this Province,” ratified on 10 May 1740, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 397–417.

[4] See section 2 of the aforementioned Act No. 670, “An Act for the better Ordering and Governing Negroes and other Slaves in this Province,” ratified on 10 May 1740.

[5] According to section V of Act No. 1990, “An Act to regulate the Courts held by the Associate Judges of this State at the conclusion of their respective Circuits; and of the Courts of Appeals held by the Judges of the Courts of Equity within this State; and for other purposes therein mentioned,” ratified on 22 December 1811, in McCord, Statutes at Large, 7: 311–14, the Court of Equity for Charleston District met on the third Monday of February and the second Monday of November in every year. City Gazette, 14 February 1820, page 3: “The Circuit Court of Equity, for Charleston District, will be held by Chancellor [Thomas] Waties, on Monday, the 21st inst. and continue its sittings for three weeks.” Charleston Courier, 28 November 1820 (Tuesday), page 2: “The Decrees of the Court of Equity, will be pronounced by His Honor Chancellor [Theodore] Gaillard, this morning, at 12 o’clock.”

[6] See Act No. 2236, “An Act to restrain the emancipation of slaves, and to prevent free persons of color from entering into this state, and for other purposes,” ratified on 20 December 1820, in McCord, Statutes at Large, 7: 459–60.

[7] Charleston Courier, 16 February 1821 (Friday), page 2: “The Court of Equity for Charleston District will commence its sittings on Monday next, the 19th inst.—Chancellor Desaussure will preside.”

[8] SCDAH, Records of the Equity Court for Charleston District, Decrees, 1821, No. 25. I have reproduced the spelling as it appears in the original text. Although this case was part of the court session that commenced in February and the decree bears the generic date “February 1821,” the docket carries the inscription “Filed March 17 1821.”

[9] John Francis (or Jean-François) Plumeau served as secretary of the South Carolina Insurance Company from 1813, and was active at St. Mary’s Church in Charleston from ca. 1816 through the 1820s. According to Brent H. Holcomb, South Carolina Naturalizations, 1783–1850 (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1985), 27, John Francis Plumeau was a “bookkeeper” from Cape François, Saint Domingue, who became a U.S. citizen on 30 January 1816. The death of John Francis Plumeau was recorded in the weekly “Return of Deaths within the City of Charleston,” held at CCPL, during the week of 25 October to 1 November 1847. He was described therein as a 61-year-old native of France.

[10] SCDAH, Petitions to the General Assembly, no date, No. 1751. I have reproduced the spelling as it appears in the original text. On the docket of this document, below the title summary, is written “W. Crafts”—the senator who reported on the petition—and the faint word “Emancipation.”

[11] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina House of Representatives, session of 1821, pages 7, 79; Journal of the South Carolina Senate, session of 1821, pages 40, 64.

[12] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina House of Representatives, session of 1821, pages 102–3. The 1821 petitions to the General Assembly to manumit slaves, which have been digitized by the South Carolina Department of Archives and History and are available through the institution’s online index, were submitted by John Carmille, Rene Peter David, Nicholas Venning, John Kelly, Philip J. Besselieu, Augustus Genty, John Renauld, John Warren, Joshua Lockwood Jr., William B. Farr, Ann Ferguson, Rebecca Drayton, Josiah Patterson, Philip Stanislaus Noisette, Jacob Myers, Mary McKee, Isaac Frazier, I. E. Holmes, Frederick Kohne, Henry Littlejohn, Mary Warham, and James Hamilton Jr. (the last five of which were approved by the committee of the House of Representatives).

[13] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Senate, session of 1821, pages 123, 127, 133, 142, 155.

[14] For more information on Demark Vesey, see Douglas R. Egerton and Robert L. Paquette, eds., The Denmark Vesey Affair: A Documentary History (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2017).

[15] See, for example, Charleston Mercury, 19 December 1822, page 1: “In Senate. Tuesday, December 10. The Senate then considered and agreed to the reports of the judiciary committee, on the petitions of Jim Paterson, Zebulon Rudolph, Wm. Gardner and Wm. C. Wiggins, praying leave to emancipate certain slaves, recommending that they prayers of the said petitioners be rejected.”

[16] SCDAH, Miscellaneous Records (Main Series), Bills of Sale, volume 5A (1823–1825), page 6.

[17] The will of Peter Labaussay, dated 16 December 1823, was proved on 23 April 1824 and recorded in SCDAH, Will Book F (1818–1826), 590; WPA transcript volume 36 (1818–1826): 1014. According to Holcomb, South Carolina Naturalizations, 19, Peter Labaussay, a “baker” from Saintonge, France, was naturalized on 4 April 1820. I did not find a death record for Peter Labaussay because the died and apparently was buried on Charleston Neck, beyond the corporate limits of the City of Charleston. The inventory of the estate of Pierre Labaussay included another enslaved woman named Catherine, aged approximately 50 years, who was valued at just $50; see the undated inventory of Peter Labaussay, “late of Charleston, baker,” SCDAH, Inventories of Estates, Book G (1824–1834), page 9–10. This woman remained in the Labaussay household and died in 1835; the weekly “Return of Deaths within the City of Charleston” includes one “Cath. Labusay,” a black female, age 70 years, native of Charleston, who died of “old age” during the week of 1–9 August 1835. The column for “condition” was left blank, but the 1831 will of Mrs. Labuassay implies that her servants lived in a state of nominal slavery.

[18] SCDAH, Miscellaneous Records (Main Series), Bills of Sale, volume 5A (1823–1825), page 69.

[19] SCDAH, Miscellaneous Records (Main Series), Bills of Sale, volume 5A (1823–1825), page 306.

[20] Peter Francis Brisson, “for myself and for the other heirs of Anthony Plumet late of this city deceased,” to Marie C. Coürsal widow Labaussay, bill of sale for $450, dated 17 August 1825. The deed describes the object of the sale as “a negro woman named Catherine formerly belong[ing] to the estate of Anthony Plumet with all her future issue and increase.” Recorded on 20 August 1825. SCDAH, Miscellaneous Records (Main Series), Bills of Sale, volume 5A (1823–1825), page 543.

[21] The will of Mary Catherine Coursal Labaussay, dated 14 April 1831, was proved on 13 June 1836 and recorded in SCDAH, Will Book H (1834–1839), 210; WPA transcript volume 40 (1834–1839): 441–44. According to Holcomb, South Carolina Naturalizations, 19, Mary Catharine Coursol Labaussay was a native of St. Domingo who became naturalized on 14 April 1831.

[22] The weekly “Return of Deaths within the City of Charleston” held at CCPL includes M. E. Labuassay, a white female, age 71 years, native of St. Domingo, who died of “old age” during the week of 5–12 June 1836 and was buried at Trinity Burial Ground. The inventory of Mrs. Mary C. Labaussay, dated 13 June 1836 and recorded in SCDAH, Inventories of Estates, Book H (1834–1846), page 172, includes eleven slaves: Hector, Felix, Zair, Clemence, Lorette, Rose, Jane, Nelly, Hagar, Alexandre, and Robert.

[23] Will of Pierre F. Brisson, dated 19 March 1843, proved on 2 March 1844, recorded in SCDAH, Will Book I/J (1839–1845), page 354; WPA transcript volume 43 (1839–1845): 738–39.

[24] Courier, 29 February 1844, page 2: “The friends of Mr. P. F. Brisson, are invited to attend his funeral from his late residence in Wolf street, at 10 o’clock, this morning.” Brisson’s death was not included in the weekly “Return of Deaths within the City of Charleston” because he died and was buried outside the city limits. Brisson’s estate was appraised in early March 1844 and recorded in SCDAH, Inventories of Estates, Book B (1845–1850), page 523–24. The sale of Brisson’s estate was advertised in Courier, 16 March 1844, page 3.

[25] For the population of Malone’s household, see the 1850 Federal census and slave schedule for urban Charleston. Malone died intestate in Charleston in early March 1864. George L. Buist administered his estate and made an inventory in August 1864; see SCDAH, Inventories of Estates, Book F (1860–1864), page 571–73. Malone’s estate was the subject of litigation between 1883 and approximately 1890. See, for example, [New Orleans] Times-Picayune, 1 February 1883, page 1: “Notice—Any persons claiming to be heirs of next of kin of Thomas W. Malone, who lived in New Orleans between 1820 and 1833, and afterward removed to Charleston, S.C. and died there in 1864, will hear something to their advantage by applying to Sam’l M. Todd, 37 Magazine Street, New Orleans, or to Watts & Sons, Attorneys at Law, Montgomery, Ala.”

[26] I am especially grateful, as always, to Steve Tuttle and rest of the staff of the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, who provided valuable assistance during my research into Catherine’s life (and so many other projects).

NEXT: The Rise of Charles Shinner, Irish Chief Justice of South Carolina

PREVIOUSLY: Freedom Won and Lost: The Story of Catherine in Antebellum Charleston, Part 1

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments