The First Football Match in Charleston, Christmas Eve 1892

Processing Request

Processing Request

The first exhibition game of American-style “scientific” football in the Lowcountry of South Carolina kicked-off in December 1892, when two teams of eleven college boys scrimmaged at Charleston’s Base Ball Park on Christmas Eve. Only a few locals had by that time seen or played the novel game developed up North, but the community’s interest was keen. Furman University brought its record to bear against the first team ever fielded by South Carolina College, battling for the title of state champion and infusing the roaring Charleston crowd with football fever.

Modern American-style football made its public debut in Charleston more than a decade after the game’s invention, but residents of the Palmetto City were amply familiar with the Old World game. Football in centuries past, in Europe, Britain, and their New World colonies, was a rather chaotic kicking game lacking standardized rules. Ad-hoc teams of footballers improvised rules to suit their circumstances, and different communities hosted different styles of play. There were no standing teams or positions or leagues to foster standardized play, and no fixed schedule of matches to attract crowds of cheering spectators rooting for their favorite teams. Nor was there a regulation ball. Prior to the commercial production of rubber products in 1850s, most footballers kicked an inflated animal bladder encased within a durable canvas or tarpaulin cover.

Sparse references to football appear in a handful of documents created during the early years of South Carolina, demonstrating that groups of juvenile colonists entertained themselves with kicking games like their European counterparts. In December 1712, for example, the South Carolina General Assembly in Charles Town ratified a law to enforce “the better observation of the Lord’s Day, commonly called Sunday.” The statute dictated “that no publick sports or pastimes, [such] as bear-baiting, bull-baiting, foot-ball playing, horse-raceing, enterludes or common plays, or other unlawfull games, exercises, sports or pastimes whatsoever, shall be used on the Lord’s Day by any person or persons whatsoever.”[1] In November 1783, just three months after the incorporation of the City of Charleston, the new municipal government ratified a similar ordinance to enforce “the better observance of the Lord’s Day . . . within the City of Charleston,” which prohibited “sports or pastimes, [such] as bear-baiting, bull-baiting, foot-balls, horse-racing, or any other public exercise or exhibition” on Sundays.[2]

Young boys in the Palmetto City played the unregulated, often-chaotic sport of football from colonial times to the American Civil War. “In old times and ante-bellum days,” recalled a local reporter in 1891, “the game of foot ball was nowhere more popular than among the youth of Charleston, and there are many now living who can well remember the grand matches played on Friday afternoon between the pupils of the public and private schools of the city, and it was no uncommon thing for boys to appear in their classes on the Monday following with bruised and battered faces and showing[,] in scarred and injured limbs[,] one of the results of the contests of the previous week.”[3]

The roots of modern soccer-style football extend back to the year 1848, when representatives of several elite British schools gathered at Cambridge University to settle a formal set of rules. The creation of a standardized form of play observed by associated teams facilitated the proliferation of intercollegiate matches, which in turn helped increase the popularity of the sport that became known as “association football” (often shortened to “soccer”). A similar meeting in London in 1863 led to a split between the kicking-and-dribbling game of football played by most schools and the kicking-and-carrying game played at the Rugby School. The Rugby game, with its distinctive oval-shaped ball, was introduced to North America during the American Civil War, inspiring a few Bostonians to improvise a hybrid of soccer and Rugby rules to suit their fancy.

Intercollegiate soccer matches commenced in New England in 1869 and expanded during the 1870s, while the inhabitants of the former Confederate States were more preoccupied with the civil and economic struggles of post-war Reconstruction. Rugby-style football also blossomed at Harvard University during this era and slowly spread to other schools like Yale, Princeton, and Columbia. Their seasonal matches increased public interest in the Rugby-based game, which spawned more collegiate teams and expanded the scope of regional competition. The nascent student league known as the Intercollegiate Football Association adopted a set of rules based on the Rugby game in Massachusetts in November 1876. In subsequent annual meetings, association members revised the rules and created the modern game through a series of small steps.

A crude but recognizable version of what we now call American-style football emerged from the intercollegiate rules adopted in October 1882. The most distinctive aspects of the game at that time were the use of a moving line of scrimmage, the concept of downs, and the requirement to move the ball forward a certain number of yards within four downs or concede possession of the ball. The latter innovation obliged teams to divide the field of play into five-yard increments, thus spawning the game’s distinctive “gridiron” field of play.

The system of downs also created moments of rest in the game, which teams of eleven players used to plan and coordinate their individual movements. This feature of the American game fostered a greater sense of teamwork and strategy than other species of football. Sports writers of the late 1880s described the novel game as “scientific” football because of its emphasis on planning and strategy. Spectators found the game more exciting because they could follow the logic and drama of a team’s offensive march across the gridiron. The emphasis on coordinated play also fostered a greater sense of team identity, which, like modern market branding, attracted followers who rallied behind their favorite teams rather than individual players.

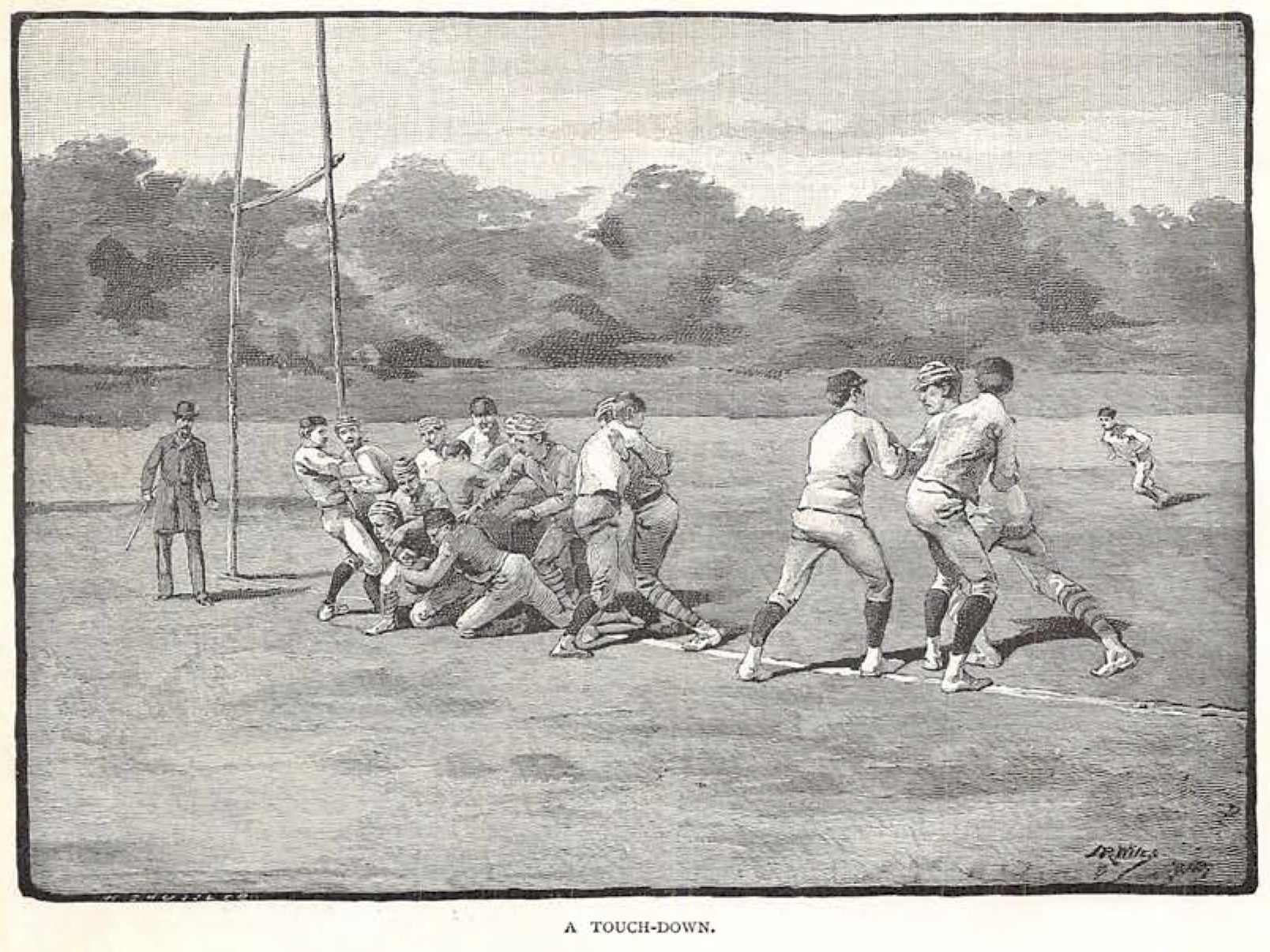

American football of the late 1880s looked and sounded much like the modern game. After the opening kickoff, the team in possession of the ball formed a seven-man “rush line” at the line of scrimmage. The captain used hand signals or code words to communicate tactical instructions to his teammates. The “centre rusher” snapped the ball to the quarter-back, who either charged across the scrimmage line or transferred possession to a half-back or full-back using a hand-off, lateral toss, or a drop-kick to a forward receiver (the rules did not permit a forward pass over the line of scrimmage until 1906). The game’s scoring system included the familiar touch-down, conversion kick, field goal, and safety, but the number of points assigned to each differed from today’s game.[4]

Meanwhile, in Charleston, baseball was by far the most popular team sport, as it had been since the conclusion of the Civil War (see Episode No. 121). Boys and young men played football, too, but they perpetuated the improvised round-ball game with few modern rules. The annual “maroon” or picnic of the Irish Rifle Club in June 1875, for example, included “a huge foot-ball match” featuring “some of the most noted ballers of the city.”[5] Similarly, on New Year’s Day 1880, members of a local militia unit, the Sumter Guards, played “a game of football by moonlight on the Citadel Green,” the former parade ground now called Marion Square.[6]

Roller skating was the newest athletic fad in Charleston during the early 1880s. In mid-November 1883, the roller rink on the west side of Meeting Street, near Horlbeck Alley, hosted a game of football between a team of skaters and a team of non-skaters from the College of Charleston. The next day, a “Grand Skating Entertainment” at Charleston’s Agricultural Hall (now the site of the Gibbes Museum of Art) included “a scientific game of foot-ball” among other exhibitions and feats of skill.[7] This 1883 reference might be the earliest mention of a game of “scientific” football in the Palmetto City—perhaps referring to the Rugby-style game—but no details survive to identify the features of this indoor match.

A number of brief articles published in Charleston newspapers during the late 1880s described the rise of the new style of football then gaining popularity on college campuses in the Northeastern states. One story pointed readers to an illustrated description of the “scientific” game in the October 1887 issue of Century Magazine, written by a professor at Princeton University. That same month, Outing magazine carried a long article describing “American football” in great detail, written by Yale alum Walter Camp, a leading figure in the sport’s early history.[8]

Such publications, augmented by the experiences of traveling students and businessmen, inspired some college boys in South Carolina to adopt the Rugby-style game. Intercollegiate football in the Palmetto State commenced in the upstate in December 1889, when a team from Spartanburg’s Wofford College beat a team from Greenville’s Furman University. Cadets of the South Carolina Military Academy at the Citadel formed “two foot ball teams” in the spring of 1890, but they were almost certainly playing “association football” (soccer) rather than the American gridiron game then popular in the Northeast.[9] The tide of interest turned towards the Rugby-style game following an exhibition match played at the South Carolina State Fair in November 1891, when a football team from Trinity College (now Duke University) defeated the Furman eleven before a large crowd in Columbia.[10]

One week after that historic match, an article in the Charleston newspaper asked “Why is there no foot ball in the South? Will it spread from the North, where everyone is wild over it?” Old-world football had always been popular in Charleston, said the article, but the popularity of the new American game had recently surpassed that of baseball in New England. The Charleston reporter polled “a number of young men” in the city, all of whom “appeared to be very favorably disposed to the establishment of a foot ball team in Charleston[,] and believed that it could be successfully inaugurated, especially among the College [of Charleston] students, the Porter School boys, the [Citadel] cadets and the pupils of the [Charleston] High School.”[11]

In the spring of 1892, students at the South Carolina College in Columbia (now USC) formed their own football squad using the American rules forged by Northern players.[12] A number of Charleston boys learned and practiced the game informally during the same season, but were not yet ready to field a competitive team. Nevertheless, Lowcountry sportsmen craved to see a skilled exhibition of the novel sport played on their home turf. In November 1892, several Charleston businessmen invited teams from Furman University and South Carolina College to play a match in the Palmetto City during their Christmas vacation. Slated for December 24th, the game was billed as a championship battle between the only two college teams then active in the state. News of the impending match in Charleston spurred a challenge from Wofford College, who proposed to play the winner for a real championship battle on December 26th. That game failed to materialize, however, so the people of Charleston focused their attention on the college boys from Greenville and Columbia.[13]

During the month of December 1892, the Charleston News and Courier published a number of articles about the upcoming football match that included anecdotes about the sport’s brief history. Most of the newspaper’s subscribers had never witnessed such a game before and were unfamiliar with its rules and character.[14] A particularly colorful description, provided by a Greenville reporter, described American football as “a sport that tests all a man’s strength and endurance, and is more like the milder Roman sports than any game now played. No child can play it. Only men or boys with hard muscles and the nerve to some times stand pain are fit to be foot ball players. . . . There is no lawn tennis about genuine foot ball. A man goes into it knowing that he may have a limb broken or his arms and face scratched.”[15]

The city was “alive with enthusiasm for the coming contest,” said another press report, and “foot ball fever” had “taken possession of the town.” Although the News and Courier conceded that “a scientific game of foot ball has never been played in this city,” its editors opined that “the people of Charleston are determined that they will avail themselves of the very earliest opportunity of witnessing one.” Baseball enthusiasts were also intrigued by the new sport, which they acknowledged possessed “exciting features which the game on the diamond never did or could possess.” Local alumni and supporters of both Furman and Carolina made plans to entertain the visiting teams and to decorate the town with their school colors. After the local press repeatedly described the new style of football as a fad, one fan chastised the newspaper and defended the novel sport. Besides the healthful benefits of manly exercise, said the anonymous writer, “there is nothing that brings an institution to the attention of the public more than the doings of its students, and success in athletics is a better advertisement for a college than any amount of distributed circulars or newspaper paragraphs concerning learned professors.” “By all means,” wrote the sportsman, “let us have the games during Christmas week, and let all the old collegians come out and whoop it up for the youngsters and give them a glorious reception. The wild antics of a crowd of college boys is the most delightful of all harmless jollifications.”[16]

Reports forwarded from Greenville and Columbia provided Charleston readers with personal details of the twenty-two White competitors, whose average weight was approximately 153 pounds. Both teams agreed to follow the published intercollegiate rules, and both promised to adhere to an additional stipulation: “That no player be allowed upon the field who is not a regularly matriculated student of one or the other of the colleges in the contest. This regulation will be strictly enforced, and the captain of each team will be required to guarantee that each and all of its players are college men, and entitled to play in the game.”[17]

As football fever spread throughout the Palmetto City, local enthusiasts organized a new sports club, the Charleston Athletic Association, on 5 December 1892. During the ensuing days, the association’s officers announced that they had formed a football team, ordered one of the curious egg-shaped balls from a distant supplier, and commenced practicing.[18] Their field of play was Charleston’s Base Ball Park, created in the early months of 1886 for the city’s first professional bat-and-ball team.[19] The four-acre park, measuring approximately 430 feet square, was located on the west side of Meeting Street, between Sheppard and Lee Streets, and was surrounded by a board fence ten feet high. Visitors entered the park through a gate in Meeting Street, near Sheppard, and walked toward the Grand Stand built at the southwest corner of the park, facing to the northeast.[20] Workers had filled, leveled, and clayed the field in 1886 for baseball play, so the footballers of 1892 probably found it a dusty venue with no grass to cushion their falls. Members of the Charleston Athletic Association staked the outline of a regulation gridiron (330 feet by 160 feet) in mid-December and used lime to mark lines in five-yard increments. The rectangular pitch stretched diagonally across the park, extending from the southeast to the northwest. In the center of each end-zone stood a pair of tall wooden goal posts standing 18.5 feet apart, joined by a vertical crossbar ten feet above the ground.[21]

By mid-December, news reports described “the approaching inter-collegiate foot ball match” as “the all-absorbing topic of conversation just at present. It is safe to say that it will be witnessed by one of the largest crowds which has ever assembled in Charleston.”[22] Two leather footballs purchased especially for the big game, both of the ovular Spalding type “J,” were displayed in the window of a book store at the corner of King and Wentworth Streets for those in the community who had never seen such an object.[23] Letters to the newspaper editor, purportedly from local ladies, expressed female interest in the coming match. One, calling herself “Charleston Girl,” said she had recently attended a game between Yale and Princeton during a northern visit and declared it “the most exciting sport that I ever witnessed.” “We should try to keep up with the times,” wrote “Matinee Girl,” who implored everyone to attend the Christmas Eve spectacle. “I wouldn’t miss Saturday’s game for three boxes of sugar plums.”[24]

The train carrying the Furman entourage arrived at Charleston’s Northeastern passenger depot at the east end of Chapel Street at 9:15 p.m. on December 23rd. A horse-drawn streetcar carried the players down the tracks through East Bay Street to the foot of Hasell Street, where they were obliged to disembark and walk 400 yards westward to their hotel. The proprietor of the St. Charles Hotel greeted the visitors at northwest corner of Meeting and Hasell Streets and ushered them inside for a hot supper. After their meal, the players jogged to Marion Square to stretch their legs after the long train ride from Greenville. The Furman boys returned to the hotel and retired to their rooms at half-past ten, before the arrival of their opponents. Their much-delayed train from Columbia did not reach Charleston until 11:25, after which the Carolina boys followed the same route to the St. Charles Hotel. The proprietor again offered the weary sportsmen a hot supper, but their manager declined, insisting that “a good night’s rest would be of more service to them to-morrow than ten suppers.”[25]

On the chilly morning of December 24th, supporters of the two teams collected the players in carriages decorated with the school colors—purple and white for Furman, garnet and black for South Carolina College. They spent some time touring the peninsular city and enjoying the sights before returning to the hotel to change into their athletic gear. The Furman boys wore “uniforms of white duck cloth, the arms of which had been dyed purple,” with caps of “white and purple.” The published description of the Carolina uniform was less precise, stating only that the Columbia eleven wore “regular foot ball shirts and red caps.” None of the players wore helmets or any of the padding adopted by later generations of footballers. Each team climbed aboard a horse-drawn omnibuses at 2 p.m. and the sporting caravan sauntered up King Street to the Base Ball Park, waving to crowds of pedestrians during the mile-long procession.

A post-game report stated that “a fair-sized audience” had gathered around the field by 3 p.m. on Christmas Eve, adults paying fifty cents for admission and half-price for “boys.” Two representatives of the Charleston Athletic Association officiated the game—the umpire, identified only as “Mr. Buist,” and G. A. Klatte as referee. Eleven young men from each team took the field for the coin toss to determine first possession of the ball. In the presence of the neutral officials, the captain of the Furman squad, W. E. Lott, pointed to his opponents and made a damning accusation. Two of the Carolina players, left-end Lawrence and center Parker, “were not matriculates of the college and, under the conditions of the game, could not play.” Umpire Buist quizzed the captain of the Carolina team and determined “that Capt. Lott was right in his protest.” The Furman players could have demanded a forfeit at this point, but, having come all the way from Greenville to battle for the state championship, Captain Lott stated that they “did not desire to break up the game.” In a gesture of good sportsmanship, the Furman team chose to proceed with the game.

At this point, I’ll let a reporter from the Charleston News and Courier narrate the championship game in the sporting manner of 1892:

“About 3:20 o’clock the teams lined up for play. The South Carolina men had won the toss and chosen the ball. The Furman men selected the goal at the southwest [sic; southeast] portion of the field, giving the College men the northwest goal. . . . In getting the ball the College men had the advantage and they used it. They formed in a wedge shape and with a tremendous rush went twenty yards into Furman’s territory. By another rush they gained five yards, and again a few yards, and in less than five minutes had only five yards to plough through the ranks of the purple and white and make a touch-down—four points—but they could not budge the sturdy mountaineers. Once it was thought they had scored a touch-down, but their man had gotten outside the lines. By failure to gain five yards in four rushes the College men lost the ball, and then Furman saw it was her chance to get out of a dangerous position. The ball was snapped to [E. G.] Stewart [the quarterback], but he fumbled it and made no gain. The next time, however, Stewart redeemed himself, and by a beautiful run around the right end gained fully twenty-five yards before he was tackled and brought to the ground. Furman tried several rushes, but made little gain. By several runs the ball was carried to the College’s fifteen-yard line, and by a good play a Furman man carried it behind the goal, scoring a touch-down. A goal was kicked by Stewart, making the score 6 to 0 in Furman’s favor.

After that the College seemed unable to do much. The University men gained by rushes and runs and again carried the ball behind the goal, thus getting another touch-down. The attempt to kick a goal failed, but the score stood 10 to 0. The teams again lined up and Furman did some brilliant playing, securing the ball, and by a repetition of the former tactics going into the College territory. About this time Furman’s quarterback, Stewart, was hurt and lay on the ground in a faint for a few minutes. When he got up he went gamely on, but five minutes later was again hurt, having been struck in the head. He staggered to his feet and resumed his position. Shortly afterward [W. H.] Lipscomb, the College’s full back, was hurt and had to quit the game. A substitute was put in his place. By repeated rushes Furman got to the College’s five-yard line and then took it over, making four points. The score was then 16 to 0. No further points were scored, and the first half ended with the College men blue and not a point to their credit.

In the second-half the College men tried hard to gain lost ground and for a while played a rattling game. They were over-matched, and by various tricks Furman’s men rushed the College boys back and soon scored. The College men attempted to gain by punting the ball, but each time lost, not only ground, but possession of the ball, which amounts to a great deal. All the College team’s tricks were futile. The Furman boys worked their famous razzle-dazzle tricks and it was as successful as it was two years [ago] with Wofford. The game ended with the score 44 to 0 in favor of Furman.”[26]

The exhausted college boys quit the field at dusk and returned to their hotel to shed their dirt-stained uniforms. The Carolina team boarded a train for Columbia shortly thereafter, while the Furman team departed on Christmas Day. A post-game report published on the 25th stated that “Charleston yesterday afternoon witnessed her first game of real football—the game as played by the great kickers of the North.” The champions had executed “brilliant runs,” “fine dodging,” and displayed “splendid” team work. The Carolina boys, on the other hand, “played an up-hill game. They played fine foot ball, but were over-matched at every point.”[27]

Cadets at the Citadel began canvassing to start a new football team immediately after the big match of December 1892. There was enthusiasm for the new game, but little experience. “More than one attempt at organizing a regular college ‘eleven’ has been made,” said a local reporter on New Year’s Eve, “but the knowledge of the game as it is played a la Furman is not sufficient among the cadets to allow of the organizing of a team that could do credit to the Academy.” Nevertheless, the Citadel’s sophomore class issued a challenge to meet local footballers at Marion Square, promising “to whip all comers who will dare to jump into the scrimmage.” “There will be no recognized rules in the game,” predicted a local reporter, “and it will be played in the old style with as many on a side as may wish to play. . . . There will be plenty of fun and exercise, but no science. By next year the cadets expect to have a team to whip anything in the state.”[28]

The Charleston Athletic Association soon afterwards fielded its own non-collegiate team in uniforms of blue and white, challenging other regional teams like Savannah and Augusta.[29] Both the College of Charleston and the Citadel assembled their own teams in the mid-1890s, and the rest, as they say, is history. The popularity of American football, rooted in the sporting traditions of Rugby School play, exploded in the early years of the twentieth century, especially at the college level.[30] Baseball continued to preoccupy the leisure time of many fans in the new century, but Charleston’s first Base Ball Park ceased hosting games of any sort by 1918, when the site was subdivided for residential housing.[31]

The debut of American-style football in Charleston in 1892 marked the beginning of a new era of Lowcountry fascination with the distinctive Yankee sport. South Carolina never attracted a professional league team, but football at the high school and collegiate levels grew exponentially in subsequent generations. The next time you’re watching a holiday bowl game of gridiron football, rooting for the college team of your choice, perhaps you’ll recall the excitement and novelty of the game more than a century ago. December is truly football month in the history of Charleston.

[1] See Section 5 of Act No. 320, “An Act for the Better Observation of the Lord’s Day, Commonly Called Sunday,” ratified on 12 December 1712, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 2 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1837), 396–99. I have reproduced the original spelling in the source.

[2] See “An ordinance for the better observance of the Lord’s Day, commonly called Sunday, and to prevent disturbances at any place of public worship within the City of Charleston,” ratified on 22 November 1783, in City Council of Charleston, Ordinances of the City Council of Charleston, In the State of South Carolina, Passed in the First Year of the Incorporation of the City. To which are Prefixed the Act of the General Assembly for Incorporating the City, and a Subsequent Act to Explain and Amend the Same (Charleston, S.C.: J. Miller, 1784), 19–21.

[3] Charleston News and Courier, 28 November 1891, page 2, “Will Charleston Catch It?”

[4] Roger R. Tamte, Walter Camp and the Creation of American Football (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2018); Tony Collins, How Football Began: A Global History of How the World’s Football Codes Were Born (New York: Routledge, 2019).

[5] News and Courier, 5 June 1875, page 4, “Pleasant Picnic in Prospect.”

[6] News and Courier, 2 January 1880, page 1, “Odds and Ends.”

[7] News and Courier, 19 November 1883, page 4, “Students Versus Skates”; News and Courier, 20 November 1883, page 2, “Grand Skating Entertainment.”

[8] See, for example, News and Courier, 5 December 1884, page 4, “News of the Day”; News and Courier, 1 November 1887, page 6, “The Magazines”; Alexander Johnston, “The American Game of Foot-ball,” Century Magazine 34 (October 1887): 888–98; Walter C. Camp, “The Game and Laws of American Football,” Outing 11 (October 1887): 68–85.

[9] News and Courier, 24 March 1890, page 8, “Our Boys In Grey.”

[10] New and Courier, 15 November 1891, page 1, “The Day After the Fair.”

[11] News and Courier, 28 November 1891, page 2, “Will Charleston Catch It?”

[12] A brief description of the team’s organization in 1891–92 appears in News and Courier, 24 December 1892, page 2, “Rah! Rah! Rah! Foot Ball.”

[13] News and Courier, 30 November 1892, page 8, “The Foot Ball Fad.”

[14] News and Courier, 18 December 1892, page 12, “The Foot Ball Fever.”

[15] News and Courier, 21 December 1892, page 2, “Furman’s Heavy Kickers.”

[16] News and Courier, 4 December 1892, page 8, “The Foot Ball Championship.”

[17] News and Courier, 18 December 1892, page 12, “The Foot Ball Fever.”

[18] News and Courier, 6 December 1892, page 8, “A Foot Ball Club”; News and Courier, 11 December 1892, page 8, “Foot Ball”; News and Courier, 18 December 1892, page 12, “Foot Ball.”

[19] The “first professional game” at Base Ball Park took place on 16 March 1886; see News and Courier, 17 March 1886, page 8, “The Great American Game.”

[20] News and Courier, 7 March 1886, page 8, “The Base Ball Season.”

[21] News and Courier, 18 December 1892, page 12, “The Foot Ball Fever”; News and Courier, 20 December 1892, page 8, “A Game of Foot Ball”; News and Courier, 21 December 1892, page 12,“The Foot Ball Game.”

[22] News and Courier, 18 December 1892, page 12, “The Foot Ball Fever.”

[23] News and Courier, 20 December 1892, page 8, “A Game of Foot Ball.”

[24] News and Courier, 21 December 1892, page 4, “Everybody Should Attend.”

[25] News and Courier, 24 December 1892, page 2, “Rah! Rah! Rah! Foot Ball.”

[26] News and Courier, 25 December 1892, page 2, “Furman’s Champions.”

[27] News and Courier, 25 December 1892, page 2, “Furman’s Champions”; a good description of this game appears in John Chandler Griffin, The Encyclopedia of Gamecock Football 1892–1994 (Lancaster, S.C.: Palmetto Press, 1995).

[28] News and Courier, 31 December 1892, page 8, “The Foot Ball Fad.”

[29] Charleston Evening Post, 12 December 1894, page 3, “The World of Sports”; Evening Post, 2 January 1895, page 3, “The World of Sports.”

[30] For more details about this topic, see Fritz P. Hamer and John Daye, Glory on the Gridiron: A History of College Football in South Carolina (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2009).

[31] News and Courier, 29 August 1918, page 10, “Eighteen Houses To Be Built Here.”

NEXT: The Beef Market under Charleston’s City Hall

PREVIOUSLY: Watson's Garden: The Horticultural Roots of Courier Square

See more from Charleston Time Machine