Emancipation Day: A New Year’s Tradition

Processing Request

Processing Request

The first of January marks the beginning of a new year and the annual observance of one of Charleston’s most important holidays. Since 1866, local citizens have celebrated the first as Emancipation Day—a joyous holiday featuring parades, pageantry, singing, dancing, orations, and religious thanksgiving. The day marks the demise of slavery and the liberation of those who once formed the majority of South Carolina’s population. Now one of Charleston’s oldest public events, Emancipation Day is a noble occasion worthy of general acknowledgment and applause, regardless of one’s creed or color.

Emancipation Day is an annual holiday commemorating the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1st, 1863. That document ordered the immediate emancipation, or liberation, of all enslaved people living in territories controlled by the Confederate States of America. The executive order did not apply to enslaved people living in the United States, north of the boundaries of the Confederacy, however. Those people had to wait until 1865 to enjoy their freedom. In effect, therefore, the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 freed a very small number of slaves in Southern areas held by the Union Army, like Beaufort, South Carolina. More importantly, however, the Proclamation effectively shifted the moral mandate surrounding the American Civil War from a fight to maintain the federal union to a fight to eradicate the institution of slavery. More than anything, the Emancipation Proclamation was a powerful rhetorical gesture, an executive order committing the collective might of the United States to the cause of ending the practice of slavery.

The people of Charleston, deep in the heart of the Confederacy, learned about President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in early January 1863 by way of telegraphic news relays. The proclamation was a symbolic gesture, ostensibly freeing enslaved people in places like Charleston, but the Confederate authorities controlling our community at that time willfully ignored the orders of a man they considered a foreign tyrant. In short, there were no public celebrations of emancipation in Charleston County on January 1st, 1863. Enslaved people in this area, who formed the majority of the local population, might have heard about Lincoln’s proclamation around that time, but they were not yet in any position to assert or enjoy their freedom.

Practical emancipation came to the enslaved people of Charleston on 18 February 1865, when the Union Army occupied the city and then spread throughout the rest of the county (see Episode No. 163). Within the first year of post-war freedom, Charleston’s African-American community organized three large public celebrations. First, on 21 March 1865, thousands of newly-freed African Americans paraded through the streets of Charleston in a massive, jubilant celebration of the “death of slavery.” Several weeks later, on the first of May, a more somber parade led to a pastoral site on the city’s north side, where formerly-enslaved people decorated the graves of fallen Union soldiers. Finally, on the first day of January 1866, Charleston’s Black community staged a day of festivities in commemoration of the third anniversary of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. This event was the first observance of its kind in Charleston, and it proved to be the cornerstone of an enduring tradition.

In the years immediately after the Civil War, numerous communities across the United States, most especially those in the Southern states, held annual celebrations to commemorate emancipation. Many cities and towns in South Carolina, including Chester, Columbia, Darlington, Florence, Georgetown, Greenville, Manning, Orangeburg, Spartanburg, and Sumter, observed January 1st as their annual day of jubilation. Other places, including several communities in Virginia and Washington D.C., celebrated Emancipation Day in mid-April, to commemorate the death of Abraham Lincoln. Still other communities, in Texas and in many mid-western locales, celebrated June 19th, or “Juneteenth,” as their anniversary of emancipation. The people of Charleston, however, have consistently observed January 1st as Emancipation Day since 1866.

From the beginning, Emancipation festivities in the Palmetto City included citizens, schoolchildren, civic clubs and organizations, church groups, labor unions, bands, and soldiers. The earliest commemorations were organized by a civic organization called the Union League, which included both Black and White men. By 1876, a new group known as the Emancipation Association, or the Emancipation Day Association, became the driving force behind the annual parade and related events. Today, the body responsible for organizing the day is called the Emancipation Proclamation Association, which descends directly from the post-Civil War organization.

Throughout the South, enthusiasm for celebrating emancipation and the promise of a bright future was at its zenith in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. During the long decade known as the era of Reconstruction, the people of Charleston County gathered by the thousands in the city to commemorate their liberation from legal bondage. “Ever since Emancipation Day got a place on the calendar,” said a Charleston news report in 1889, “the streets are practically surrendered to legions” of Americans of African descent on the first of January.[1] Celebrants gathered on Calhoun Street during the early years of the tradition and paraded southward with brass bands playing festive music all the way to White Point Garden. Within that public park, a succession of distinguished orators read aloud the text of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, recited prayers, and delivered political speeches to inspire the citizens. It was, in many ways, the winter antipode to Black celebrations of the Fourth of July at White Point Garden, which also attracted massive crowds to the park during the 1870s (see Episode No. 72).

The political and legal atmosphere of the Reconstruction era brought new rights and opportunities to the Black community, but the bubble burst in the late 1870s. As the Federal government allowed White members of South Carolina’s antebellum regime to reassert control over local politics, the rights and liberties of Black citizens quickly withered (see Episode No. 177). In many communities across the South, annual public celebrations of emancipation began to disappear. The rise of legally-mandated segregation and racial inequality during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, commonly called Jim Crow politics, induced many African Americans in the South to conduct their commemorations within private gatherings, or simply in the context of church services.

Charleston’s City Council, for example, ratified an ordinance in 1881 prohibiting military parades and political oratory within White Point Garden, a change that disrupted African-American traditions and forced the Emancipation Association to re-route its annual parade.[2] In the decade following, celebrants continued to parade south of Calhoun Street but concluded their march at Hampstead Mall, before that historic greenspace was bisected by Columbus and America Streets (see Episode No. 131). City Council denied the Association permission to use the mall after 1892, however, forcing organizers to experiment with alternate routes.[3] Marion Square served as the home base for numerous parades around the turn of the twentieth century, as did a succession of Black churches such as Emanuel A.M.E., Zion Presbyterian, and Morris Street Baptist Church, among others.

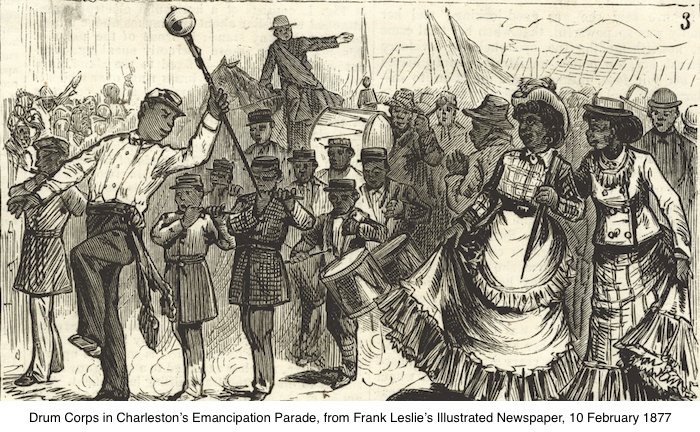

It may surprise some in our community to learn that one of the principal features of the early Emancipation Day events was the colorful appearance of the local units of the South Carolina militia. In the wake of the Civil War, Federal authorities oversaw a complete reorganization of the militias in the Southern states, and in the spring of 1869 the old South Carolina Militia became the new South Carolina National Guard. For more than a decade after that transformation, the state’s local National Guard was composed almost exclusively of Black citizen-soldiers. Between 1870 and 1905, each of Charleston’s Emancipation Day parades included hundreds of uniformed Black soldiers bearing arms, including horse-mounted cavalry. Black veterans of the Civil War also participated under the fraternal order of the Grand Army of the Republic. The presence of such martial forces, organized into distinct companies and marching with practiced discipline, literally set the pace for the annual parades and imbued the scene with a strong sense of patriotic pride.

Following the end of Reconstruction in the late 1870s, the South Carolina National Guard included both Black and White men, though organized into segregated units. The reduction of state appropriations to Black militia units in the late 1890s, precipitated by the prejudicial state constitution of 1895, thinned the number of Black citizens-soldiers participating in local parades around the turn of the twentieth century. The last of South Carolina’s all-Black militia companies disbanded in the late spring of 1905, when the state dramatically reduced its National Guard in compliance with a federal law enacted in 1903.[4]

Looking back at newspaper accounts of Charleston’s Emancipation Day festivities in the years after the state eliminated the Black militia units, it appears that the annual parades lost a bit of steam without the military presence. The Emancipation Association stepped up its organizational efforts to fill the void, however, and the annual commemorations continued unabated. After 1905, the parades became more civic-oriented, with women and school children playing increasingly important roles. The Jenkins Orphanage band, for example, stepped in to fill the shoes of the defunct militia bands, historically composed of Black musicians. After World War II, the famous orphanage band morphed into the Burke Industrial School Band, which eventually became the Burke High School Band. To the present day, the Burke band has proved to be the backbone of the annual Emancipation Day processions.

The connection between Burke High School and the annual commemorations of emancipation predate the Second World War, however. Beginning in January 1937, participants inaugurated the present tradition of gathering at Harmon Field, the municipal playground opposite Burke High, and marching southward towards Calhoun Street. That parade was also the first public celebration after several fallow years. Economic hardship within the community, caused the Great Depression, induced participants to eliminate the annual parade in 1933–36. The boisterous parade resumed in 1937, but was again laid aside in 1938. The Emancipation Association paraded again in 1939, but not in 1940. After marching through the streets to commemorate Emancipation in 1941 and 1942, the Association scaled back events for the remainder of World War II. Since January 1946, however, Charlestonians have celebrated Emancipation Day with an unbroken tradition of New Year parades commencing from Harmon Field and Burke High School.

Whatever the color of your skin or the geography of your ancestry, the annual commemoration of the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation is a major event on the Charleston calendar. Besides commemorating an event of monumental importance in our nation’s history (to wit, the end of slavery), Charleston’s annual Emancipation Day celebration is a unique phenomenon. Extant newspapers confirm that there has been a public celebration of Emancipation Day in Charleston every New Year’s Day since 1866, although a handful years did not include a street parade. No other community in the United States, to my knowledge, has sustained a comparable annual tradition of public commemorations since the conclusion of the American Civil War. Other cities and towns and villages have held similar Emancipation Day events, to be sure, but none appear to be as old or as continuous as those that commenced in Charleston on the first of January 1866.

If you’re interested in observing or participating in Charleston’s Emancipation Day celebration, I encourage you to direct your attention to local media providing details of the annual event. The parade usually starts in the forenoon of January 1st at Burke High School on Fishburne Street. From that site, bands, floats, and revelers will likely wind their way down King Street, from Sumter Street to Calhoun Street, and then disband in front of Emanuel A.M.E. Church. If you’re in the city on the day, why not take a few minutes to visit the parade route and give a cheer? Take a few photos, share them with friends and family on social media, and spread the word. In our nation’s long and often troubled history, what anniversary is more fitting for a jubilant celebration on New Year’s Day?

[1] News and Courier, 1 January 1889, page 8, “The Old and the New.”

[2] “An Ordinance to amend Chapter VIII of the Revised Ordinances of the City—Title ‘The Battery and White Point Garden,” ratified on 22 March 1881, in G. D. Bryan, comp., The General Ordinances of the City of Charleston, S.C., and the Acts of the General Assembly Relating Thereto (Charleston, S.C.: News and Courier Book Presses, 1882), 194.

[3] News and Courier, 29 December 1892, page 3, City Council Proceedings of 27 December 1892.

[4] South Carolina reduced its militia in compliance with the Federal “Dick” Bill of 1903; Evening Post, 20 May 1905 (Saturday), page 1, “All the Cavalry To Be Disbanded”; News and Courier, 27 May 1905, page 2, “Sixteen Are Disbanded.”

PREVIOUS: Charleston’s Victory Day, Part 2

NEXT: The New “New Year” of 1752

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments