Denmark Vesey's Winning Lottery Ticket

Processing Request

Processing Request

I’m feeling lucky today. I’m going to take a chance and attempt to draw your attention to the historical intersection of three entirely separate but related topics: Denmark Vesey, lotteries, and Charleston’s iconic “High Battery” seawall. I’m not an expert on the subject of Denmark Vesey, but I hope to contribute something to the conversation about the man and his times by offering some insight into the means by which he purchased his freedom at the turn of the nineteenth century. To accomplish that goal, we’ll have to explore Charleston’s economic climate at the end of the eighteenth century. Trust me—it’ll all make sense shortly.

Denmark Vesey is a well-known figure in Charleston history, despite the fact that very few details of his life can be found in the surviving documentary record. His execution in the summer of 1822, as the purported leader of a suspected slave uprising, has engendered a large body of literature that seeks to understand the man, the charges against him, and the wave of white paranoia that spread throughout South Carolina in the wake of what has become known as the “Denmark Vesey affair” of 1822.

If you’ve read anything about Denmark Vesey, you’ve probably heard the following anecdote: In the autumn of 1799, an enslaved man name Telemaque living in the city of Charleston purchased a winning lottery ticket. With his prize money, Telemaque purchased his own freedom and became a “free person of color” who called himself Demark Vesey. The rest, as they say, is history. Being a stickler for details, however, I’ve been curious about the facts surrounding this important biographical anecdote. What sort of lottery was this? What were the odds? How much money was involved? Are there any surviving details about this episode that might help us re-imagine the scene and better understand Telemaque? To search for answers, we’re off to the Time Machine!

In the 1790s and early 1800s, the young United States of America witnessed a profusion of lotteries held in several states. Most were designed to raise funds for the construction of major projects, such as roads, bridges, canals, and churches. In the lowcountry of South Carolina, for example, there was a lottery to fund the Agricultural Society, the Botanic Society, the Santee Canal Company, the Second Presbyterian Church of Charleston, and so on. The municipal government of Charleston also dabbled in this fund-raising method, sponsoring at least eleven lotteries in the first three decades of its existence.

The City of Charleston was incorporated by an act of the state legislature on 13 August 1783. Three months later, the new City Council announced its first lottery scheme. Why? As City Council stated in late November 1783, they felt an “extreme reluctance” to impose any taxes on their constituents who were just beginning to recover from eight years of war. After mature deliberation on this subject, Council “determined to avail themselves of the aid of a lottery,” which they considered “as a substitution of a voluntary assessment, in lieu of a compulsory one.” Recognizing that this mode of raising funds “in some measure partakes of the nature of gaming,” Council hoped that their goals of restoring order to the city would “justify means which would be otherwise exceptionable.” (see South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, 29 November 1783).

The City of Charleston’s first lottery was organized, drawn, and paid in first half of 1784 (the details survive in the local newspapers of that era if you’re interested). At that same time, the state legislature authorized the City of Charleston to dismantle the colonial-era fortifications at the southern tip of the Charleston peninsula, then subdivide the demilitarized land into lots, and sell the lots at auction. The site in question was originally a low-lying beach that formed the eastern face of what was generally called White Point, at the southern tip of the peninsula. Between the 1730s and the 1770s, this area had been built up with a series of fortification projects that included brick sea walls faced with palmetto logs, earthen ramparts, and wooden cannon platforms. In the second half of 1784 and the early months of 1785, however, all of the accumulated fortifications were demolished.

As this work was being done, the state legislature passed a law on 24 March 1785 empowering the City Council of Charleston to extend East Bay Street southward to White Point. This was the beginning of the project that created Charleston’s granite seawall, commonly called the High Battery, and East Battery Street. Two months after receiving permission from the legislature, on 6 May 1785, City Council passed an ordinance to impose a special tax assessment on the owners of the lots along what is now East Battery Street. As you might imagine, the people who had just purchased demilitarized building lots at this site were not happy. They had paid top dollar for prime waterfront real estate in late 1784, only to learn six months later that they were going to be taxed for the privilege of having the city confiscate some of their new property for the extension of East Bay Street. This situation did not bode well for the future.

In the summer of 1785, the City of Charleston began spending money on laborers and materials (including pine logs, palmetto trunks, and ballast stones) to build up a road bed and protective sea wall were there had once been a beach in front of the old fortifications. At the same time this work was progressing, however, the new owners of the recently-subdivided land at White Point began grumbling about the damage to their property and the unwanted tax burden that they alone shouldered for a project that would benefit the entire city. Between 1786 and 1789, the new property owners at White Point negotiated with the state legislature and the City Council of Charleston to revise the tax assessment scheme and to re-appraise and even re-sell the property in question. Meanwhile, progress on the new street and seawall was slow and underfunded.

In Charleston’s City Gazette of 24 September 1790, an anonymous correspondent observed “that it is the wish of the citizens in general, that the [city] corporation should fall on some plan to finish the works on East Bay; and as no method can be fallen on so little burthensome [sic] to the public as a lottery for that purpose, he conceives such a plan very eligible, and is well convinced that the tickets would be eagerly purchased.” Two weeks later, City Council resolved to launch another lottery effort, and soon published a detailed plan of the scheme. The City of Charleston’s second municipal lottery was held in the spring of 1791, then a third in the summer and autumn of 1791, and a fourth took place in 1792. Each of these lotteries was advertised as a means of raising capital to cover general city expenses, but the project to extend East Bay Street southward was the city’s largest money pit of that era.

In Charleston’s City Gazette of 24 September 1790, an anonymous correspondent observed “that it is the wish of the citizens in general, that the [city] corporation should fall on some plan to finish the works on East Bay; and as no method can be fallen on so little burthensome [sic] to the public as a lottery for that purpose, he conceives such a plan very eligible, and is well convinced that the tickets would be eagerly purchased.” Two weeks later, City Council resolved to launch another lottery effort, and soon published a detailed plan of the scheme. The City of Charleston’s second municipal lottery was held in the spring of 1791, then a third in the summer and autumn of 1791, and a fourth took place in 1792. Each of these lotteries was advertised as a means of raising capital to cover general city expenses, but the project to extend East Bay Street southward was the city’s largest money pit of that era.

In early 1793, the percolating tensions between Great Britain and the new French Republic erupted into war. The citizens of South Carolina, and the rest of the United States, feared they would be forced to choose sides in this new European war and be drawn into the conflict. In order to be prepared for such a contingency, our governor and legislature ordered the construction of new waterfront fortifications at White Point, on the site of the colonial-era works that had been demolished in 1785. This project added another level of complexity to the sensitive negotiations between the City of Charleston and the post-war purchasers of that decommissioned real estate. In order to satisfy all the interested parties, the trajectory of the new southern extension of East Bay Street had to be adjusted to go around the east side of the new fortification, called Fort Mechanic, that was erected in 1794–1795. After further negotiations and compromises between the state and local parties, this re-working of new East Bay Street continued until a hurricane in September 1797 ruined much of its progress.

By 1798, the City of Charleston had spent at least $13,000 on credit to extend East Bay Street southward and to build a new seawall to protect it from the daily tides. In the wake of the 1797 hurricane, the city had little to show for its effort, and there was no money in the treasury to repair and finish the work. On 15 October 1798, City Council ratified an ordinance to sink its $13,000 debt with tax revenues and to raise an additional $6,000 to complete “New East Bay Street” by way of a lottery or lotteries. Accordingly, in November 1798 the local newspapers published the scheme for the first of what would become seven separate East Bay Street Lotteries. The first lottery included 3,000 tickets at $5 each, with a single grand prize of $1,000 and hundreds of lesser prizes (the lowest prize being a $6 ticket in the second lottery). In fact, there were over 1,000 prizes that consumed nearly $12,000 of the $15,000 gross proceeds. This scheme, which brought a net of $3,052 into the city treasury, might seem a bit foolish, but it’s important to remember the times. Lotteries were generally seen as a form of gambling, which was generally viewed as distasteful. By offering very good odds that nearly one in three participants would recoup at least the price of their ticket, the city hoped to foster good will in the community and thereby slowly achieve its goal.

The commissioners of Charleston’s first East Bay Street Lottery commenced drawing numbers from the “wheel of fortune” in mid-July 1799 and continued doing so for ten business days. In early August, the city treasurer began paying out the prize money to the holders of “fortunate tickets.” This is an important detail of the entire scheme: no prize money was dispersed until after all of the numbers had been drawn, at the conclusion of the entire scheme. Thus, the earliest prize winners had to wait at least two weeks to receive their cash.

Details for the “second lottery” authorized by the city ordinance of October 1798 first appeared in the City Gazette of 12 August 1799. This was to be a bigger venture, offering 3,300 tickets at $6 each, with a single grand prize of $1,500 and hundreds of lesser prizes. Like the first lottery, the odds were very good and the profits rather small. A total of 908 prizes consumed the bulk of the gross income, leaving a net profit of $4,150 to the city. The initial advertisement for this scheme noted that the lottery commissioners had “no doubt but the citizens of Charleston have remarked the effects of their support to the completing of the First Lottery, as the works on East Bay street are now in a prosperous state of forwardness, and more ease and convenience for passengers is intended to be made thereon, by extending the walk to South-Bay.” The commissioners optimistically projected that the drawing of numbers would commence in early October, and, as usual, “the prizes be paid ten days after the drawing is finished.”

Tickets could be purchased from any of the lottery commissioners (John Champneys, James Lowndes, Charles G. Corre, William Turpin, and Thomas Somarsall), or from any of the following gentlemen: William Blacklock and “Freneau & Paine” on East Bay; David Alexander; Lynn, Weyman & Co., and W. P. Young on Broad Street; John Ward on Church-street; John Potter on Tradd-street; John Cunningham, Abraham Markley, or “Robertson & Sons” on King Street; or from the City Treasurer, William Roach, or the City Sheriff, Jervis Henry Stevens.

Ticket sales for the second East Bay Street Lottery did not meet expectations, however, and the lottery commissioners were apprehensive about beginning the drawing of prizes. After some delay, the first drawing was held on October 9th, then suddenly stopped. The lottery was undersubscribed. The commissioners consulted City Council, and then resolved to wait a few more weeks. If a greater number of tickets could be sold, the drawings would continue. If not, the lottery scheme might collapse. Fortunately for all involved, the drawings recommenced on October 23rd, and were continued on each successive Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.

Ticket sales for the second East Bay Street Lottery did not meet expectations, however, and the lottery commissioners were apprehensive about beginning the drawing of prizes. After some delay, the first drawing was held on October 9th, then suddenly stopped. The lottery was undersubscribed. The commissioners consulted City Council, and then resolved to wait a few more weeks. If a greater number of tickets could be sold, the drawings would continue. If not, the lottery scheme might collapse. Fortunately for all involved, the drawings recommenced on October 23rd, and were continued on each successive Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.

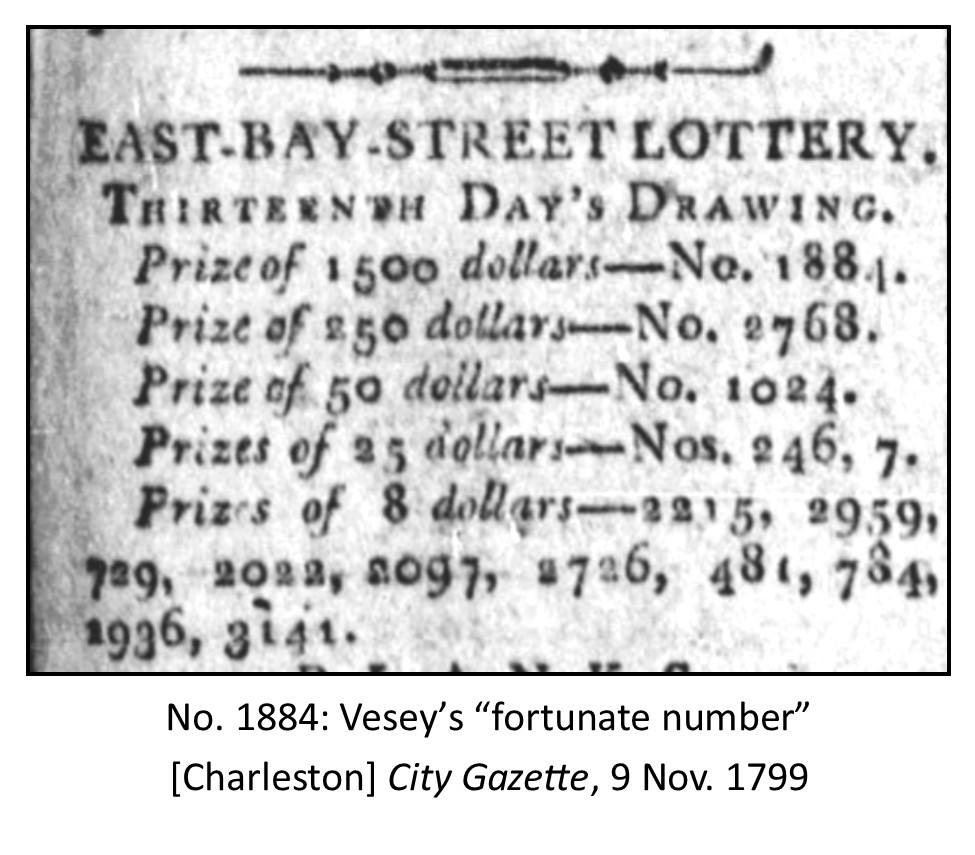

On Friday, November 8th, 1799, the thirteenth day of drawing for the second East Bay Street Lottery, the city treasurer drew the number 1884 from the “wheel of fortune” to receive the grand prize of $1,500. This number, we now know, had been purchased by the enslaved man named Telemaque. He had probably raised the money to purchase the $6 ticket by being “hired out” to work beyond his master’s home, a common arrangement in urban Charleston at that time that allowed enslaved workers to pocket a small portion of their daily wages. I know of no record that tells us how Telemaque reacted to this news, but we can imagine the elation he experienced on hearing his winning number whispered through the town, or seeing it printed in the local newspapers the following day. (Some histories of Denmark Vesey state that he won the lottery on 9 November 1799, but that it simply the date his winning number appeared in the newspaper, the day after the drawing).

The drawing of prize numbers in the second East Bay Street Lottery continued until December 11th, 1799. In accordance with its published rules, the city treasurer did not begin dispersing prize money until ten days after the last day of drawing. This fact means that Telemaque, aka Denmark Vesey, could not have collected his $1,500 in prize money until December 21st at the earliest. That day was a Saturday, however, so I’ll wager that the city treasurer, William Roach, did not being paying lottery prizes until Monday, December 23rd. Why does this detail matter? Because Telemaque purchased his freedom from his master on Saturday, December 7th, 1799, at least two weeks before he actually received his prize money.

The document recording Telemaque’s manumission, or release from slavery, is recorded among the Miscellaneous Records of the Secretary of State, a large and valuable collection of manuscripts housed about the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia. The document in question (volume 3M, pages 427–28) was created by Telemaque’s owner, an east-Indian woman named Mary Clodner who was the common-law wife of Captain Joseph Vesey. It is a single paragraph of text, dated December 7th, simply stating that in consideration of the sum of $600, Mary Clodner has released Telemaque from the yoke of slavery. Mary’s signature was witnessed by two men—her husband, Joseph Vesey, and Charles G. Corre, one of the commissioners of the city lottery. (Some historians assert that Telemaque was freed on 31 December 1799, but his manumission is clearly dated 7 December. After that date, the manumission contract was presented to the Secretary of State and recorded or copied into a volume of the secretary’s records on 31 December. The execution of the contract and its recording are two separate events).

The presence of Charles G. Corre is significant to the chronology of this story. Although Telemaque’s winning number was drawn on November 8th, he was unable to claim his cash prize until the third week of December. On Saturday, December 7th, then, the enslaved man’s prize money existed only in theory, or “on credit.” As an enslaved man with a head full of the promise of riches, Telemaque must have started bargaining with his owner shortly after his winning number was drawn. Perhaps he was impatient to be free and pleaded for manumission as soon as possible. Lottery commissioner Charles Corre was a business man well known in the community, and no stranger to the Vesey family. We might imagine that Mary Clodner or Joseph Vesey asked Mr. Corre to confirm the legitimacy of Telemaque’s claim. As a lottery commissioner, his testimony would have been both credible and creditable. Yes, Corre could confirm, ticket No. 1884 was indeed the grand prize winner, and cash in the amount of $1,500 would be forthcoming sometime in late December. With Mr. Corre’s corroboration of the facts, Telemaque could pledge to pay Ms. Clodner as soon as he received the prize money. Following his manumission, Telemaque took the name Denmark Vesey, and the rest, as they say, is history.

So, what became of the East Bay Street project that inspired the lottery that freed Telemaque? In accordance with the designs of the city ordinance of October 1798, the City of Charleston sponsored two lotteries in 1799 that produced a profit of over $7,000 to fund the extension of East Bay Street and the construction of a new protective seawall. The citizens of Charleston witnessed a great deal of progress on the waterfront during first half of the year 1800, only to see most of that work washed away by a strong hurricane in October. “But although this barrier suffered so much,” stated the City Gazette, 31 July 1801, “if it had not been for it, the whole of that part of the city would have been in ruins.” So important was this project, that the city embarked on a “third lottery” in the autumn of 1801 to rebuild and finish the new East Bay Street. “When completed,” the lottery commissioners opined in 1801, the work will present “an agreeable walk for passengers, and for carriages going round from East-Bay to South-Bay-street. They flatter themselves that from these inducements, and from the punctuality of payment of prizes in the two former lotteries, the inhabitants of this commercial city will support the plan now proposed, to raise the deficiency wanted for the completion of the work.”

After East Bay Street Lottery No. 3 in 1801, Lottery No. 4 was drawn and paid in the summer of 1802. By the beginning of 1804, the new street and seawall were being used and admired by the citizens of Charleston. The hurricane of September 1804 completely annihilated the work, however, and so East Bay Street Lottery No. 5 commenced in November 1804 and finished in June 1806. The city announced Lottery No. 6 in January 1809 and it dragged on to late June 1810. The seventh and final East Bay Street Lottery commenced in August 1810 and drew its last numbers in mid-January 1811. In the summer of 1818, the city laid the final stones in the “Battery” seawall, as it was immediately known, but the city’s legal wrestling with outstanding funds from the various East Bay Street lotteries lingered until September 1820.

During each of these successive city lotteries, I can think of at least one man who must have watched the construction of what we now call the “High Battery” with a mix of hope and satisfaction. The man known to his masters as Telemaque, who chose the name Demark Vesey in freedom, may have witnessed the entirety of Charleston’s thirty-three-year project to build a seawall and street linking East Bay Street to South Bay Street. Enslaved by a peculiar institution legal at that time, Telemaque’s life was radically transformed by a fortuitous opportunity, a lottery born of a curious circumstance of the post-war economy. Denmark Vesey lived long enough to promenade on the completed Battery, perhaps even with members of his family or friends. Before his date with destiny arrived in 1822, we might imagine him leaning against the seawall’s railing on a summer’s day, looking across the harbor and enjoying the breeze, remembering how a $6 ticket in the autumn of 1799 changed his life—and the history of Charleston.

PREVIOUS: Remembering Rhettsbury

NEXT: The South Carolina Constitutional Convention of 1868

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments