Demilitarizing Urban Charleston, 1783–1789

Processing Request

Processing Request

For the first century of its existence, the urban landscape of Charleston was dominated by an evolving ring of fortifications designed to protect the city against potential invasion by Spanish, French, and later British forces. Our provincial legislature repeatedly devoted large sums of tax revenue for the construction and repair of walls, moats, bastions, and related works, resulting in what was undoubtedly the largest public works program in colonial South Carolina. Despite the impressive scale of this work, however, Charleston’s modern streetscape reveals scarcely any physical trace of those early fortifications. If the city once bristled with cannon, walls, moats, and drawbridges, how and when were such features scoured from the historical landscape?

Many of the details concerning the demilitarization of urban Charleston can be found in the public records created in the immediate aftermath of the American Revolutionary War. Although incomplete, these records provide sufficient information to construct a robust outline of the decisions, issues, and events that took place between 1783 and 1789 and resulted in a dramatic alteration of Charleston’s urban landscape. During this brief period, both state and city governments worked in tandem to survey, dismantle, and sell the accumulated urban fortifications. The evidence of this cautious transition from defensive stronghold to peaceful commercial port provides two principal lessons for modern historians to consider. On the local scale, the demolition of Charleston’s urban fortifications produced some of the most valuable documentary evidence of their dimensions, composition, and location. On the national scale, this story presents a local example of the larger American struggle to chart a new civic course in the tumultuous environment of the Age of Revolution.

As tensions between England, France, and Spain heated and cooled during Charleston’s colonial century, between the 1670s and the 1770s, so too did the perceived necessity of the town’s defensive works. The fear of Spanish invasion preoccupied generations of South Carolinians from the colony’s infancy until the conclusion of King George’s War in 1748. The French menace began with the settlement of Biloxi in 1699 and evaporated with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763. After a dozen years of neglect, the fortifications of Charleston were rehabilitated and substantially expanded between 1775 and 1780 to ward off British assaults. The American forces surrendered Charleston in May 1780, but the British occupying forces repaired and strengthened the town’s fortifications in case of an American counterattack. After nearly three years of occupation, British forces demolished some of the fortifications and evacuated Charleston in mid-December 1782. Within a month’s time, the South Carolina legislature was back in session in the state house in Charleston. At the beginning of 1783, therefore, the city and the nation entered a period of sustained peace, but after a century living in a defensive posture, civic and military leaders were hesitant to abandon Charleston’s extensive fortifications.

In late January 1783, Governor John Mathews addressed the South Carolina House of Representatives concerning Charleston’s military readiness. “The defenceless state in which this town and harbour have been left by the enemy, requires some immediate & decisive measures to be taken for the security of both.” With that aim in mind, Mathews forwarded to the House a plan for strengthening the fortifications of Charleston that he had received from General Nathanael Greene, who also offered to supervise the work. Governor Mathews then informed the House that he had received information about peace negotiations between American and British ambassadors taking place in Paris. While encouraged by this news, Mathews warned the lawmakers to be wary of their recent enemy. “We have been so long amused with the pacific disposition of the Court of Great Britain, that we have evr’y thing to apprehend from her insidious vigilance.” “Therefore to be substantially prepared for war,” Mathews advised, “will be the most effectual means to disappoint her ambitious views, and secure to ourselves an honourable and advantageous peace.”[1] In its reply to the governor’s speech, the House of Representatives acknowledged “that immediate and decisive measures, for the security of this town and harbour, and for the protection of our trade are highly necessary,” and pledged to support General Greene’s plan. The House also seconded Governor Mathews’s reluctance to trust Britain’s overtures towards peace, and endorsed his recommendation to sustain a defensive posture: “The accounts of the pacific dispositions of the Court of Great Britain, we can never look on but as a delusive cover to her secret and insidious intentions until the establishment of the independence of the United States of America in a general peace to be concluded in concert with our allies; to procure which, speedily and effectually, it is a duty, incumbent on us to provide vigourously for war, and to hold in readiness those means, which can check her ambition and counter act her designs.”[2]

On receiving General Greene’s plan and budget estimate for defending Charleston, the House referred the matter to a special committee “to consider the state of the republick.”[3] In the meantime, to curtail the pilfering of the materials composing the old works, the legislature also appointed a second committee “to devise ways and means for preventing the fortifications being pulled down.”[4] After several weeks of debate, the first committee reported their approbation of General Greene’s plans. They recommended that the proposed additional defensive works for urban Charleston should be undertaken immediately and forwarded the details to newly elected Governor Benjamin Guerard. [5] In late March 1783, the governor’s Privy Council unanimously advised him to execute the new fortification plan immediately.[6]

Shortly after the legislature adjourned for the spring, however, news arrived that the preliminary articles of peace between Britain and the United States had been ratified by the American Congress in Philadelphia. Upon receiving this news in late April, Charleston nearly exploded with celebrations, feasting, and toasting.[7] When the legislature reconvened in early August 1783, Governor Guerard curtly reported to the House of Representatives “the fortifications ordered by the General Assembly were not carried into execution on account of the peace.”[8] For the remainder of 1783, therefore, the now-obsolete fortifications of urban Charleston were largely ignored.

The United States Congress ratified the definitive treaty of peace with Britain in mid-January 1784, and news of this event reached Charleston by the end of the month. Almost immediately, on February 6th, the state House of Representatives approved a report from the Committee on Ways and Means recommending that a bill be drafted appointing commissioners to ascertain the boundaries of “the several forts, fortifications, and low water lotts [sic] belonging to the public within the city of Charleston,” who would be authorized “to dispose of the same at public auction.”[9] After several weeks of debate and modification, that bill, called “An Ordinance for the Sale of the Public Lands Whereon the Forts and Fortifications Were Erected, and Low-Water Lots within the City of Charleston, and The State Ship-Yard at Hobcaw, and the Island of Pollawahnas, in St. Helena Parish,” was ratified on 26 March 1784.

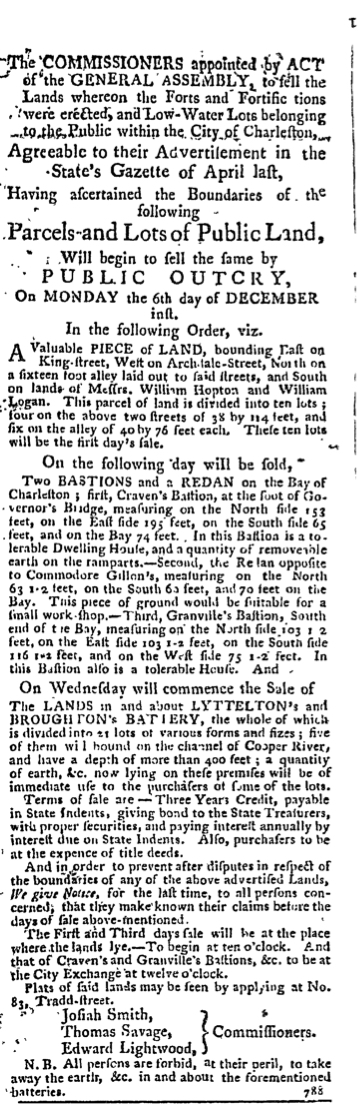

The law to dispose of the fortifications appointed three men, Josiah Smith, Thomas Savage, and Edward Lightwood, who were subsequently identified as “the Commissioners for the Sale of Public Lands in Charleston.” As soon as they had determined the boundaries of the fortified lands, the commissioners were “to expose to public sale (giving three months previous notice thereof in the public gazette) all the land whereon the forts and fortifications were erected, and low-water lots, belonging to the public, within the city of Charleston.”[10] In mid-April 1784 the commissioners published the first advertisement of the upcoming sales. The sale of the state shipyard at Hobcaw would take place on 15 July 1784, while the sale of the other forts and fortified lands in the city of Charleston would be advertised at a later date, “as soon after as their boundaries can be ascertained.” In addition, the commissioners stated, there was also available “a considerable quantity of brick work within the several forts, &c. which they will put up for sale in lots as they now stand.”[11] On 15 July 1784, the date appointed for the auction of the state shipyard at Hobcaw, the state commissioners appointed to dispose of the fortified lands also sold the bricks forming two large gun batteries near the southeastern tip of the Charleston peninsula: Broughton’s Battery, constructed in the mid-1730s, and Lyttleton’s Battery, built in the late 1750s.[12]

In the meantime, the commissioners’ efforts to ascertain the boundaries of Charleston’s urban fortifications dragged on for nearly eight months before the first sales were advertised. What at first may have seemed to be a relatively simple task of surveying and measuring the lands on which defensive works stood turned into a tangled legal question that required documentary research, interviews, and negotiations. The primary causes for this confusion boiled down to two issues: the incorporation of the city of Charleston and the incomplete records kept by the colonial government.

During the entire colonial period of South Carolina, the provincial governor and General Assembly administered Charleston’s municipal affairs, but the incorporation of the city in August 1783 effectively divided the urban fortifications between two jurisdictions. After defining the general boundaries of the city, the act of incorporation more specifically articulated certain lands to be vested in the city council, including most of the marsh lands, the water lots at the ends of the streets, and the land occupied by the large fort known as the Horn Work, built principally of tabby in the late 1750s.[13] Unfortunately, the details of how and when the city of Charleston disposed of the fortifications under its jurisdiction in the Post-Revolutionary era are clouded by the scarcity of extant city documents. With a few fragmentary exceptions, the proceedings of Charleston’s City Council do not survive prior to 1836, and thus it may be impossible to learn the details of this matter. Nevertheless, a number of useful clues can be found in contemporary newspapers. Published financial accounts, for example, demonstrate that in 1784, City Council paid nearly £300 “for leveling the Horn-work,” the site of which now forms the city’s Marion Square.[14]

The remaining fortifications vested in the City Council of Charleston included the brick “curtain line,” standing six feet tall and running nearly 2,700 feet along the east side of East Bay Street between Craven and Granville Bastion, and three brick redans or “salient angles” near the east end of Lodge Alley, the east end of Unity Alley, and the east end of Tradd Street. How and when these works were dismantled is less clear, and these questions certainly merit further investigation. The bulk of the defensive works standing within the city’s corporate limits remained under state control, however, and the responsibility of their disposal fell to the Commissioners for the Sale of Public Lands in Charleston. Despite the large and obvious nature of these works, the commissioners struggled to define their legal boundaries.

Charleston’s urban fortifications were built on lands that had been granted originally to private individuals, but, during episodes of high tension with Spain and France, the provincial government had exercised its right of eminent domain and seized private property in order to construct gun batteries, walls, moats, and other defensive works. Such actions were largely negotiated on the spot with property owners who either acquiesced to the will of the public or complained loudly to the General Assembly. The surviving legislative journals record a few such complaints from the early eighteenth century, and during the 1740s the Assembly made a concerted effort to satisfy earlier claims and to offer compensation for the owners of lands engulfed by new works. The records of these transactions provide valuable information about the location and date of certain episodes in the expansion of Charleston’s urban fortifications, but the surviving records do not encompass the entirety of the property condemned for defensive purposes. Some parties were clearly compensated for the title to their condemned lands in a timely manner, while others waited for generations to receive proper satisfaction. By 1784, therefore, the Commissioners for the Sale of Public Lands in Charleston were unable to determine with confidence which parts of the city’s fortified property were fully vested in the state. Hampered by such challenges and pressed to fulfill their duties in a timely manner, the commissioners moved forward by selling only those properties for which they felt the state held an uncontestable title.

Charleston’s urban fortifications were built on lands that had been granted originally to private individuals, but, during episodes of high tension with Spain and France, the provincial government had exercised its right of eminent domain and seized private property in order to construct gun batteries, walls, moats, and other defensive works. Such actions were largely negotiated on the spot with property owners who either acquiesced to the will of the public or complained loudly to the General Assembly. The surviving legislative journals record a few such complaints from the early eighteenth century, and during the 1740s the Assembly made a concerted effort to satisfy earlier claims and to offer compensation for the owners of lands engulfed by new works. The records of these transactions provide valuable information about the location and date of certain episodes in the expansion of Charleston’s urban fortifications, but the surviving records do not encompass the entirety of the property condemned for defensive purposes. Some parties were clearly compensated for the title to their condemned lands in a timely manner, while others waited for generations to receive proper satisfaction. By 1784, therefore, the Commissioners for the Sale of Public Lands in Charleston were unable to determine with confidence which parts of the city’s fortified property were fully vested in the state. Hampered by such challenges and pressed to fulfill their duties in a timely manner, the commissioners moved forward by selling only those properties for which they felt the state held an uncontestable title.

It was not until mid-November 1784 that the Commissioners for the Sale of Public Lands began advertising the auction of state-owned properties in urban Charleston. According to their published notices, the commissioners began on 6 December 1784 to dispose of the fortified lands at public auctions over three consecutive days. On the first day they sold a rectangular tract of land between King and Archdale Streets, divided into ten lots, on which had once stood an earthwork wall, moat, drawbridge, and the northern gate into the town between 1745 and 1764 (now part of Market Street). On the second day they sold three brick structures on the east side of East Bay Street: Craven Bastion at the northern end of the street street (now occupied by the U.S. Custom House), Granville Bastion at the southern end of the street (now occupied by the Missroon House), and a redan near the eastern end of Lodge Alley. On the third day, 8 December 1784, the commissioners sold the land once occupied by Lyttleton’s and Broughton’s Batteries at White Point, divided into seven and fourteen lots respectively.[15]

In the weeks following the December 1784 sales, some members of the state legislature enquired if the commissioners had in fact disposed of all of the property that was eligible to be sold. In late February 1785, the Commissioners for the Sale of Public lands in Charleston acknowledged that they had some reservations about whether or not the state held legal title to certain fortified lots. “We therefore thought it prudent to confine ourselves in the sale of public lands to that part only which we found clearly vacant,” they reported to the House of Representatives, “being altogether at a loss how to proceed further than we have done, without involving ourselves into numberless disputes.” The commissioners had examined many of the old journals of the colonial Commons House of Assembly and interviewed some of the older members of the community in order to find relevant details, but their efforts uncovered more confusion than useful evidence. A moat, earthen wall, and several gun batteries had once stood on a rectangular tract of land between Archdale and Meeting Streets, for example, but the commissioners sold only the western half of the tract. The eastern half was now partially occupied by houses and gardens, and they were not confident of the state’s legal right to the property. Rather than evict the current residents and risk initiating an untenable litigious battle, the commissioners opted to proceed conservatively and to err on the side of caution. So insecure were the commissioners about the precise boundaries of lands that had been condemned for public use decades before, that they closed their remarks by asking the legislature to pass an act “to indemnify us for what we have sold.”[16]

A year later, in late February 1786, the House Committee on Ways and Means reported that they had examined the accounts of the Commissioners of Public Lands in Charleston and, to their dismay, had found “large balances remaining which very much embarras [sic] the finances of this state.” Many of those who had purchased fortified lands and bricks at auction on credit had not rendered payment according to their bonds, and the House recommended that the commissioners be urged “in the most pressing terms to have their accounts closed with all possible expedition.” The Post-Revolutionary economy of Charleston, like much of the United States, was crippled by a lack of specie and by the loss of traditional commercial networks. Planters and merchants alike were forced to rely heavily on credit and faith, but, in the years immediately after the war, patience and cash were both in short supply. For those parties who were not able to come to an “immediate settlement” with the state “agreeable to the terms of sale,” the House ordered that the commissioners “either commence actions against them, or in cases where the law authorises [sic] it, the lands be again disposed of.”[17]

In late March 1786, the South Carolina General Assembly passed a law authorizing the Commissioners of the Public Lands in Charleston to re-sell those lots on which the original purchasers had defaulted. According to this new act, the original purchasers were offered a grace period of six months in which they were invited to comply with the terms of their agreements with the commissioners. After the third day of October 1786, however, the commissioners notified the purchasers remaining in arrears that “they must then expect to be dealt with as the law directs.”[18] Between 1787 and 1789, a number of lots forming parts of the colonial fortifications were seized and again sold at auction, and the Commissioners of the Public Lands in Charleston continued to struggle to collect the monies. Again, in March 1789, the legislature passed another law authorizing the re-sale of several of the fortified lots, and as late as December 1793, the House of Representatives was still arguing with purchasers of fortified lands, some of whom complained that the lots had been improperly surveyed and the prices they agreed to pay in 1784 had been painfully and unfairly inflated.[19]

From a historical perspective, the abandonment and demolition of Charleston’s colonial fortifications in the 1780s provides a rich opportunity to improve our understanding of this city. Using this episode as a lens to peer further back into the city’s early history, we see that the complicated process of disposing of the old defensive works provides a useful means of studying their initial construction and physical arrangement. Many plats were created to accompany the sales and re-sales of the fortified lands, and the contemporary newspaper advertisements and legislative journals also contain valuable descriptions of the properties in question. From these resources we can refine our understanding of the location, dimensions, and materials composing the long-forgotten works that once defined the city’s landscape.

From a historical perspective, the abandonment and demolition of Charleston’s colonial fortifications in the 1780s provides a rich opportunity to improve our understanding of this city. Using this episode as a lens to peer further back into the city’s early history, we see that the complicated process of disposing of the old defensive works provides a useful means of studying their initial construction and physical arrangement. Many plats were created to accompany the sales and re-sales of the fortified lands, and the contemporary newspaper advertisements and legislative journals also contain valuable descriptions of the properties in question. From these resources we can refine our understanding of the location, dimensions, and materials composing the long-forgotten works that once defined the city’s landscape.

Looking forward, toward the city’s more recent past, the demolition of Charleston’s colonial fortifications in the wake of the American Revolution represents an important turning point in the development of the city’s urban landscape. For the entirety of its first century, the town slowly expanded to accommodate its growing population, but Charleston was always constrained by the military works made necessary by lingering fears of Spanish or French invasion. Beginning in 1784, however, the city took its first tentative steps towards an unfettered use of the peninsular landscape. The Post-Revolutionary extension of Charleston’s streets, the development of its boroughs, gardens, and public green spaces, and the commercial expansion of its port facilities were all predicated on the removal of the restrictive colonial fortifications. The “charm” of modern Charleston certainly embraces many colonial features, but few traces now remain of what was once the largest and most imposing of the city’s early characteristics. By retracing the steps undertaken in the 1780s to bring down the walls and fill in the moats, however, we can begin to see the outlines of one of the most significant physical transitions in the city’s history.

[1] Theodora J. Thompson and Rosa Lumpkin, eds. Journals of the House of Representatives, 1783–1784 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1977), 33–34 (24 January 1783).

[2] Ibid., 56–57 (28 January 1783).

[3] Ibid., 42 (25 January 1783).

[4] Ibid., 64 (29 January 1783).

[5] Ibid., 213 (4 March 1783).

[6] Adele Stanton Edwards, ed., Journals of the Privy Council, 1783–1789; The State Records of South Carolina series (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1971) 11 (26 March 1783).

[7] South-Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, 26 April 1783.

[8] Thompson and Lumpkin, Journals of the House of Representatives, 1783–1784, 322 (2 August 1783).

[9] Thompson and Lumpkin, Journals of the House of Representatives, 1783–1784, 426 (6 February 1784).

[10] Thomas Cooper, ed., Statutes at Large of South Carolina, Vol. 4 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1838), 648–49.

[11] South-Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, 15–17 April 1784.

[12] South Carolina Department of Archives and History, General Assembly and Other Miscellaneous Records (series S390008), “The Commissioners for the Sale of the public Lands for the Account Sales with the State of So. Carolina,” 4 September 1794.

[13] David J. McCord, ed., Statutes at Large of South Carolina, Vol. 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 97–101.

[14] Charleston Evening Gazette, 1 September 1785. Similar charges for “leveling the Horn Work” appear in several subsequent years as well, suggesting that the city executed the work in 1784 but took several years to pay for it.

[15] South-Carolina Gazette and Public Advertiser, 13–16 November 1784. Although these twenty-one lots were sold into private hands in 1784, the city of Charleston later repurchased most of this land to extend East Bay Street southward, to build the Battery seawall, and to create White Point Garden at the southern extremity of the peninsula.

[16] Lark Emerson Adams and Rosa Stoney Lumpkin, eds., Journals of the House of Representatives 1785–1786 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1979), 144–45 (25 February 1785).

[17] Adams and Lumpkin, Journals of the House of Representatives 1785–1786, 463.

[18] State Gazette of South-Carolina, 11 September 1786.

[19] See Thomas Cooper, ed., Statutes at Large of South Carolina, Vol. 5 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1839), 132–34, “An Ordinance for the Sale of Sundry Lands Belonging to the Public, and for Appointing Commissioners to Purchase other Lands for the Purpose of Erecting Store Houses, and Having Tobacco Inspected in or near Charleston”; Michael E. Stevens and Christine M. Allen, eds., Journals of the House of Representatives, 1789–1790 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1984), 77; Michael E. Stevens, ed., Journals of the House of Representatives, 1792–1794 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1988), 357.

PREVIOUS: The Men who Built St. Michael’s Church, 1752–1754

NEXT: The Slippery Enchanter of 1876: Charles Barker Nixon

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments