Declaring Independence in 1776 Charleston

Processing Request

Processing Request

On the Fourth of July, our nation commemorates the anniversary of the ratification of the fundamental document in the long history of the United States. On that date in 1776, our Continental Congress, a loose confederation of “united colonies” meeting in Philadelphia, adopted a joint mission statement they called a “Declaration of Independence.” Here in Charleston, we gather on this date each year to commemorate, as well, a grand event that is less-well remembered—the first publication of the Declaration of Independence in the capital city of South Carolina, which took place on August 5th, 1776.

The American Revolution commenced in April of 1775, when festering political tensions between Great Britain and some of her colonial provinces in North American erupted into violent clashes. One by one, thirteen of these colonies turned away from their traditional forms of government and established new legislative bodies. Like her northern neighbors, South Carolina started down this path in the spring of 1775 and gradually moved towards a sort of improvised home rule. On the 26th of March, 1776, the South Carolina Provincial Congress adopted its own Constitution that established the offices of a president, a Legislative Council, and a House of Representatives to govern the colony. The purpose of this document was not to declare sovereignty or independence, however. Rather, the South Carolina Constitution of 1776 articulated the framework of a temporary system of provincial government that would keep the colony running “until an accommodation of the differences between Great-Britain and America shall take place.”[1]

Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, delegates from the thirteen separate provinces assembled as a body they called the Continental Congress of the “United Colonies.” Their original purpose had been to lobby jointly for a settlement of tensions between Britain and her American colonies, but the prospects for peaceful resolution faded during the escalating violence of 1775. The move towards the idea of American sovereignty and towards a formal declaration of independence took place gradually during the spring of 1776. The text of the document itself was crafted and debated over a period of many weeks that June. After ratifying the text of the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, the Continental Congress ordered 200 copies to be printed for immediate distribution so that its text could be “proclaimed in each of the United States and at the head of the Army.”

On July 9th, the South Carolina representatives to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia assembled a bundle of official documents, including copies of a number of Congressional resolutions and the Declaration of Independence, and handed these materials to a courier with instructions to deliver them to John Rutledge, President of South Carolina, in Charleston. That courier, riding overland along a recently-completed postal highway that connected each of the thirteen colonies, arrived in Charleston nearly two weeks later, on Friday, August 2nd.[2] (It would have been faster to send the Declaration in a sailing vessel from Philadelphia to Charleston, but a squadron of the British Navy was then blocking the entrance to Charleston harbor, and had recently clashed with American troops stationed on Sullivan’s Island.) When the courier arrived in Charleston with the packet of official documents, the civilian President of South Carolina, John Rutledge, and the ranking military commander, General Charles Lee, immediately commenced preparations for the public proclamation of this important document on Monday, August 5th.

The people of Charleston in 1776 were no strangers to the pomp and circumstance surrounding the public proclamation of official government documents. From the earliest days of the colony, Charlestonians had routinely heard government officials read aloud the text of newly-ratified laws and important occasional proclamations. This was an ancient practice inherited from Europe, the vestige of an era in which the vast majority of the population was illiterate and public access to written documents was limited. In Latin, the act of reading or “publishing” documents aloud was called publication by viva voce—literally by “the living voice.” In early modern England, this act was called publication “by beat of drum”—a reference to the fact that a drummer was traditionally used to summon the populace to bend their ears to the publication of important information.

The people of Charleston in 1776 were no strangers to the pomp and circumstance surrounding the public proclamation of official government documents. From the earliest days of the colony, Charlestonians had routinely heard government officials read aloud the text of newly-ratified laws and important occasional proclamations. This was an ancient practice inherited from Europe, the vestige of an era in which the vast majority of the population was illiterate and public access to written documents was limited. In Latin, the act of reading or “publishing” documents aloud was called publication by viva voce—literally by “the living voice.” In early modern England, this act was called publication “by beat of drum”—a reference to the fact that a drummer was traditionally used to summon the populace to bend their ears to the publication of important information.

In colonial-era Charleston, the provost marshal of South Carolina (later the sheriff of Charleston District) routinely paraded through the streets of the town with a drummer and stopped at multiple landmarks to read aloud the text of laws and proclamations. If you have in mind a quaint old image of a man walking through the streets ringing a hand bell and shouting “Hear ye, hear ye,” I implore you to banish those thoughts and replace them with the images of a white man and an enslaved drummer parading through the town with a profusion of pomp and a bit of circumstance.

On more important occasions in colonial Charleston, such as the publication of royal declarations of war, the colony’s civil and military leaders assembled on the streets to enact a similar but grander series of public readings. For these “state” occasions, the secretary of the province usually read aloud from the official document, line by line, while the clerk of His Majesty’s Council, standing next to the secretary, repeated each phrase in a much louder voice—probably with the aid of a “speaking trumpet” or megaphone. This was the practice employed in 1740, 1744, 1756, and 1762, for example, when the townsfolk of Charleston gathered to hear the text of the king’s declarations of war against France and Spain. Furthermore, the provost marshal of South Carolina also attended the public readings of these royal declarations, on which occasions he unsheathed the ceremonial sword of state, held it aloft before the assembled multitudes, and brandished it three times to the sound of great cheers from the crowd.[3]

The surviving documentary descriptions of the public proclamations of the Declaration of Independence in Charleston in 1776 are fragmentary and lamentably incomplete. Several eye-witnesses, including William Moultrie, William Henry Drayton, Barnard Elliott, and William Tennent, wrote brief descriptions of this historic events, but each of their respective descriptions is incomplete. Viewed individually, they’re a bit confusing, and even misleading. Stitched together with a bit of care, and infused with a knowledge of colonial-era precedents, however, these eye-witness descriptions paint a reasonably satisfactory narrative of the events that transpired on August 5th, 1776.

The population of Charleston in the summer 1776 included more than 12,000 souls, at least half of whom were enslaved people of African descent. In addition, there were approximately 5,500 out-of-town soldiers stationed around Charleston at the time.[4] To afford all of these people an opportunity to hear the text of the Declaration, there had to be multiple public readings at several different locations.

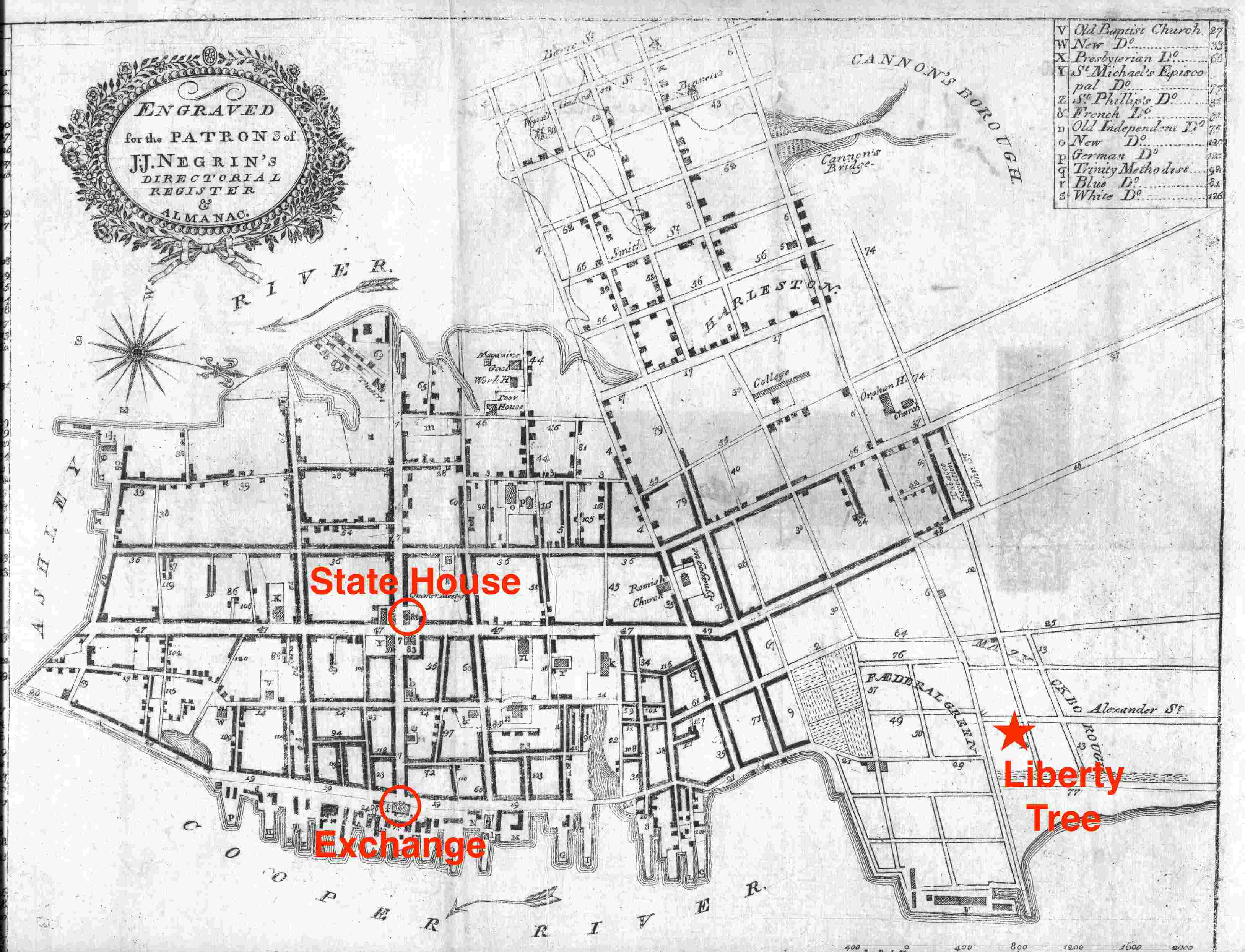

The first recitation took place near—perhaps adjacent to—the South Carolina State House, located at the northwest corner of Broad and Meeting Streets. At noon on August 5th, the Charleston Regiment of militia, consisting of approximately 700 citizen-soldiers, paraded under arms in Broad Street and formed a series of ranks from east to west. At 12:45, “the President [of South Carolina, John Rutledge] accompanied by Major General [Charles] Lee [of Virginia], Brigadiers [Robert] How[e, of North Carolina] & [John] Armstrong [of Pennsylvania,] with the Privy Council, Legislative Council, members of the House [of Representatives] & Officers of the [Continental] Army went in procession to the head of the regiment [near the west end of Broad Street] and attended the reading of the Declaration of [Independence adopted by the] General Congress.”

The first recitation took place near—perhaps adjacent to—the South Carolina State House, located at the northwest corner of Broad and Meeting Streets. At noon on August 5th, the Charleston Regiment of militia, consisting of approximately 700 citizen-soldiers, paraded under arms in Broad Street and formed a series of ranks from east to west. At 12:45, “the President [of South Carolina, John Rutledge] accompanied by Major General [Charles] Lee [of Virginia], Brigadiers [Robert] How[e, of North Carolina] & [John] Armstrong [of Pennsylvania,] with the Privy Council, Legislative Council, members of the House [of Representatives] & Officers of the [Continental] Army went in procession to the head of the regiment [near the west end of Broad Street] and attended the reading of the Declaration of [Independence adopted by the] General Congress.”

The surviving records of this first reading neglect to mention many specific details that occupy my curiosity, but a bit of logic can help us fill a few blanks. Since the state legislature was not currently in session, I suspect the reading did not take place inside the State House, but rather in the street, adjacent to that public building, to enable the soldiers standing at the head (west end) of the column, as well the assembled civil and military officials (numbering approximately 250 men), to hear the official text. If this ceremony followed colonial precedents, the un-named orator was probably the Secretary of State, Capt. John Huger (1744–1804). If they employed the two-man method of publishing the text viva voce, then the words spoken aloud by Captain Huger were perhaps repeated, line by line, by Mr. Thomas Farr Jr. (1754–1827), who served as Clerk of the Legislative Council of South Carolina. Thomas Grimball III (1744–1783) served as Sheriff of Charleston District in 1776, and thus would have been responsible for brandishing the ceremonial Sword of State on this public occasion.[5]

Next, at approximately 1:30 p.m. on August 5th, the official text of the Declaration was carried to the west side of the Exchange building, “where it was read a second time, with the acclamations of the people & [the] discharge of cannon at Granville’s & Broughton’s Bastions.” The audience for this second reading included the east end of the militia column extending down Broad Street, as well as many hundreds of the general population who packed into East Bay Street and all around the Exchange building.[6]

A third reading of the Declaration took place on the north side of town, under the canopy of a large live oak tree once known as the Liberty Tree. Although its precise location is now lost, contemporary sources describe the Liberty Tree as standing in Mr. Mazyck’s pasture, just south of modern Charlotte Street, and just east of modern Alexander Street. Charleston’s revolutionary-minded gentlemen gathered here on various occasions between 1766 and 1776 to discuss their grievances against the British government. A general order issued by Major General Charles Lee on August 4th directed all the Continental soldiers in the town, who were not on duty, to assemble at the Liberty Tree at 3 p.m. on August 5th to hear Major Barnard Elliott read the Declaration aloud, and to hear the Reverend William Percy preach a sermon suitable to the occasion. After the conclusion of these solemn proceedings, the soldiers in blue responded with musket volleys and outbursts of patriotic fervor.[7]

A third reading of the Declaration took place on the north side of town, under the canopy of a large live oak tree once known as the Liberty Tree. Although its precise location is now lost, contemporary sources describe the Liberty Tree as standing in Mr. Mazyck’s pasture, just south of modern Charlotte Street, and just east of modern Alexander Street. Charleston’s revolutionary-minded gentlemen gathered here on various occasions between 1766 and 1776 to discuss their grievances against the British government. A general order issued by Major General Charles Lee on August 4th directed all the Continental soldiers in the town, who were not on duty, to assemble at the Liberty Tree at 3 p.m. on August 5th to hear Major Barnard Elliott read the Declaration aloud, and to hear the Reverend William Percy preach a sermon suitable to the occasion. After the conclusion of these solemn proceedings, the soldiers in blue responded with musket volleys and outbursts of patriotic fervor.[7]

The Reverend William Tennent III, who witnessed the events of August 5th, 1776, remarked that “no event has seemed to diffuse more general satisfaction among the people. This seems to be designed as a most important epocha [sic] in the history of South Carolina, & from this day it is no longer to be considered as a colony but as a state.”[8]

Henry Laurens, then a member of South Carolina’s Privy Council, described the day’s events in a letter to his son, John Laurens, in London. “This Declaration was proclaimed in Charles Town with great solemnity on Monday the 5th inst. attended by a procession of President, Councils, General Members of Assembly[,] Officers Civil and Military &ca. &ca. amidst loud acclimations of thousands who always huzza when a proclamation is read. . . . There I saw that Sword of State which I had before seen four several times unsheathed in Declarations of War against France & Spain by the [two King] Georges now unsheathed & borne in a Declaration of War against George the third.”[9]

The 5th of August, 1776, was truly a historic day in Charleston, but the act of proclaiming our American independence continued throughout the month. On August 6th, the Declaration was again read aloud before the soldiers, citizens, and enslaved people stationed at Fort Johnson on James Island, and at Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island. In the days afterwards, hand-written copies of the Declaration were circulated throughout the state to enable all South Carolinians to draw strength from its powerful words.

When the South Carolina General Assembly convened at the State House in mid-September, 1776, they immediately and officially embraced the Declaration of Independence as the compass of their future proceedings. On September 20th, they addressed President Rutledge in the following carefully selected words: “It is with unspeakable pleasure we embrace this opportunity of expressing our satisfaction in the Declaration of the Continental Congress, constituting the United Colonies free and independent States, absolved from allegiance to the British Crown and totally dissolving all political union between them and Great Britain, an event unsought for and now produced by unavoidable necessity, and which every friend to justice and humanity must not only hold justifiable as the natural effect of unmerited persecution, but equally rejoice in, as the only effectual security against injuries and oppressions and the most promising source of future liberty and safety.”[10]

Charleston’s enthusiastic and positive initial reception of the Declaration of Independence was repeated in 1777, not on August 5th, but on the Fourth of July—the date on which the final text of the document was ratified by Continental Congress.[11] In every subsequent year, Charlestonians have commemorated the anniversary of the Declaration in various ways, and with varying degrees of enthusiasm, but the idea of a public reading or proclamation of its text fell into obscurity long ago. In 2013, members of the Washington Light Infantry, a venerable militia unit dating back to 1807, convinced the City of Charleston to renew the practice by staging a public reading of the Declaration on the west side of the old Exchange building, just as it was done at that location on August 5th, 1776. Now voiced each Fourth of July by a chorus of diverse voices reading in turn, the Declaration of Independence continues to inspire crowds of patriotic Charlestonians who gather, as did our ancestors, on Broad Street to hear this historic text.

Written documents are, in a manner of speaking, the time-traveling devices of our shared civilization. They contain vibrant human thoughts once voiced aloud, then fixed in dry ink as silent statements. As such, they pass quietly through the years from one generation to the next, with varying degrees of notoriety. Critics might describe a particular text as expressing power, grace, or wit, but, in truth, these are latent qualities that we must interpret in our minds. When read aloud by the living voice (viva voce), however, the tacit spirit of the old text is reawakened, and the voices of past are conjured into the present for brief moment.

The Declaration of Independence of the United States of America is a powerful source of energy driving the American time machine. More than 240 years ago, this document was spoken aloud, debated, revised, even shouted, and then recorded in ink for posterity. On the Fourth of July, our nation celebrates the birthday of the concept of the United States. Here in the City of Charleston, we also invoke the vitality contained within the text the Declaration of Independence by giving living voice to that venerable document. In so doing, we recall the roots of our imperfect union, the brashness of the very concept of an American republic, and the sacrifice of the men and women who have labored through the ages to preserve and refine the American experiment we too-often take for granted.

[1] See Terry W. Lipscomb, “The South Carolina Constitution of 1776,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 77 (April 1976): 138–41. The text of this document can be found in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 1 (Columbia, A. S. Johnston, 1836), 128–34.

[2] A letter accompanying this bundle noted that “the express [rider] is to be paid for every day that he is detained in Carolina.” See William Edwin Hemphill, et al., eds., The State Records of South Carolina: Journals of the General Assembly and House of Representatives 1776-1780 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1970), 69–79. The South Carolina and American General Gazette, a loyalist newspaper, briefly noted the arrival in Charleston of the express rider carrying the Declaration in its issue of 2 August 1776.

[3] See the descriptions of the public recitals of the King’s declarations of war against France on 19 July 1744; against France on 28 August 1756; and against Spain on 20 May 1762, in the Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, No. 11, part 2, pp. 414–6; No. 25, pp. 341–42; and the un-numbered Council journal of January 1761–December 1762, pp. 498–503, all of which can be found at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia.

[4] The number of troops in Charleston in the summer of 1776 can be found in John Drayton, Memoirs of the American Revolution, volume 2 (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1821), 282, 292.

[5] For the identity of the several state officers elected on 27 March 1776, see Peter Timothy, ed., Journal of the Provincial Congress of South Carolina, 1776 (Charleston, S.C.: Peter Timothy, 1776), 122. Note that Henry Laurens’s letter to John Laurens, dated 14 August 1776 (see below), mentions the Sword of State on this occasion.

[6] The sole documentary source describing the first and second of the Declaration in Charleston is the Diary of William Tennent, 5 August 1776, which is held by the South Caroliniana Library at the University of South Carolina.

[7] The reading at the Liberty Tree was mentioned by William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, volume 1 (New York: David Longworth, 1802), 184; by Drayton, Memoirs of the American Revolution, 2: 315; by Barnard Elliott in “Diary of Captain Barnard Elliott,” in Charleston Year Book, 1889, 235; and by Joseph Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences Chiefly of The American Revolution in the South (Charleston, S.C.: Walker and James, 1851), 189.

[8] Diary of William Tennent, 5 August 1776.

[9] David R. Chesnutt, et al., eds., The Papers of Henry Laurens, volume 11 (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1988), 228.

[10] See Hemphill, Journals of the General Assembly and House of Representatives 1776–1780, 67–68.

[11] For a description of the local celebration of the Fourth of July in 1777, see the Gazette of the State of South Carolina, 7 July 1777.

PREVIOUS: Remembering the Battle of Sullivan’s Island

NEXT: Policing Charleston during Queen Anne’s War, 1702-1713

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments