Clementia Mineral Spring: Ghost Town that Never Was

Processing Request

Processing Request

Along a shady stretch of Highway 162 in Hollywood, South Carolina, stands a humble marker for Clementia Village. Local lore describes this site as the location of forgotten “ghost town,” but a search for its history reveals a different story. Formerly a part of a large rice plantation, the land bubbled with a font of spring water after the earthquake of 1886. The property owner marketed the wholesome, restorative powers of the mineral-rich water during the early years of the twentieth century, but the site devolved under a cloud during the turbulent Jazz Age.

Approximately fourteen miles due west of the Charleston Peninsula, there’s a fork in the road at the junction of Highway 17 and Highway 162. Follow 162 two miles to the southwest of that intersection, you’ll see a small, lonely sign for a tract of private property called Clementia Village. If you’re familiar with the golf community called “The Plantation at Stono Ferry,” the village in question is directly opposite. If you’re familiar with the new Hollywood-St. Paul Library branch, Clementia Village is five miles to the northeast of that awesome facility. I have it on good authority from a long-time resident of the neighborhood that “Clemen-cha” is the customary local pronunciation.[1]

Some months ago, a library colleague at the Hollywood-St. Paul branch brought to my attention a curious fact: There are a few questionable websites that identify Clementia Village as one of South Carolina’s forgotten “ghost towns.” That term doesn’t necessarily imply a haunted place, of course, but rather a site that once hosted some sort of settlement community but is now vacant. So, my colleague asked, was Clementia really a village? If so, what happened to it? If not, how did the legend of the ghost town originate?

At that time, I had never heard of Clementia. A quick Internet search yielded nothing particularly helpful in this case, so I turned to a 1941 publication titled Palmetto Placenames. This useful little book contains hundreds of brief histories of placenames from across South Carolina, collected and arranged alphabetically by writers working for the government during the Great Depression of the 1930s. It defines “Clementia” in the following words: “Charleston County—Named for Moultrie Clement who owned the land on which the village was built. Former name, Clementia Springs, for mineral springs which were discovered after the earthquake in 1886.”[2]

At that time, I had never heard of Clementia. A quick Internet search yielded nothing particularly helpful in this case, so I turned to a 1941 publication titled Palmetto Placenames. This useful little book contains hundreds of brief histories of placenames from across South Carolina, collected and arranged alphabetically by writers working for the government during the Great Depression of the 1930s. It defines “Clementia” in the following words: “Charleston County—Named for Moultrie Clement who owned the land on which the village was built. Former name, Clementia Springs, for mineral springs which were discovered after the earthquake in 1886.”[2]

That brief summary provided enough information to facilitate a deeper search for details. During the past few weeks, I’ve followed the paper trail of the site’s history and found the answers to our original questions. Clementia Village was—and still is—a business name. It was never a town or proper village; the legend of the ghost town apparently grew from a misinterpretation of the description published in Palmetto Placenames. Yes, there was a “village” of sorts at the site prior to 1941, but it wasn’t strictly residential, and it was totally distinct from the mineral spring with which it shares a name.

Although Clementia is not a bona-fide ghost town, there’s still an interesting story behind the history of the site and its name. The rise and fall of a place called Clementia is a drama in two acts—a study in contrast covering nearly a century, set in a timeless Lowcountry landscape. The curtain rises to reveal the historic parish of St. Paul, in the years shortly after the Civil War, when the land in question was still part of Colleton County.

Moultrie Johnston Clement (1855–1916) was a young Charleston attorney who began acquiring rural property in the Lowcountry during the late 1870s, around the time of his marriage to Lucia Taliaferro Taylor (1862–1917). Her father was a prominent land surveyor in St. Paul’s Parish, and that family connection probably contributed to the growth of Clement’s real estate portfolio.[3] By the early 1880s, Moultrie Clement was one of the most prominent rice planters in parish, owning thousands of acres spread across multiple sites. His principal holding was Dungannon Plantation, which contained nearly 3,000 acres of swampy rice fields, pine forest, and pasture land, plus an old residence and outbuildings. Like most of their peers among the Lowcountry gentry, the Clements resided in urban Charleston for part of the year and sojourned occasionally at their country estate.[4]

The buildings of Charleston shook violently during the earthquake of August 31st, 1886, but the quake’s epicenter was farther to the west. The most severe effects were felt at the northern and southern ends of the fault line, near the town of Summerville and near Dungannon Plantation, respectively. At these twin locations, approximately fifteen miles apart, fissures, sand spouts, and craters on the landscape gave visual proof to the natural upheaval below the surface of the earth.[5]

The buildings of Charleston shook violently during the earthquake of August 31st, 1886, but the quake’s epicenter was farther to the west. The most severe effects were felt at the northern and southern ends of the fault line, near the town of Summerville and near Dungannon Plantation, respectively. At these twin locations, approximately fifteen miles apart, fissures, sand spouts, and craters on the landscape gave visual proof to the natural upheaval below the surface of the earth.[5]

Several days after the destructive quake, Moultrie Clement visited Dungannon to check on the condition of the earthen banks surrounding his rice fields. According to a later statement, Clement reported finding a number of “wide and deep openings in the earth” and several springs of water “shooting five feet above the level of the ground.” One such spring, found among a stand of pine trees, vented a strong sulfurous smell that was perceptible from a great distance. On closer examination, Clement found the water gushing from the spring to be cool, clear, bubbly, and delicious.[6]

The discovery of a productive mineral spring in September 1886 did not immediately captivate Mr. Clement’s attention, however. After surveying the earthquake damage at his plantation, he focused on repairing his various properties and furthering his professional career. He ignored, for the time being, the newly-created springs at Dungannon, which he believed to be temporary features that would soon disappear as the landscape settled.

Two months after the earthquake, voters elected John Peter Richardson III to be governor of South Carolina. In January 1887, Richardson appointed Clement to his staff and made him a colonel in the South Carolina militia. Colonel Clement, as he became known, spent much of the next four years in Columbia and on the road with the governor.[7]

Meanwhile, the productivity of Clement’s real estate in Colleton County was in a state of flux. The Lowcountry’s long tradition of rice cultivation continued for many years after the Civil War, but the demise of enslaved labor, repeated floods, and the earthquake of 1886 forced planters like Moultrie Clement to experiment with other ventures. While many property owners turned to truck farming, Clement cleared land for pasturage in the 1880s to raise cattle and sheep.[8]

Through regular visits to Dungannon, the Clements saw that the odoriferous spring that first appeared in the autumn of 1886 was still bubbling above the surface year-round, regardless of droughts or tides or seasons. The water collected in a small crater around the spring and the overflow ran a short distance to the north or northwest to a slow-moving stream called Log Bridge Creek. The Clements sampled the naturally-carbonated water and apparently shared volumes of it with friends, family, and neighbors. After a few years, they came to regard the spring as the plantation’s most valuable asset.

Through regular visits to Dungannon, the Clements saw that the odoriferous spring that first appeared in the autumn of 1886 was still bubbling above the surface year-round, regardless of droughts or tides or seasons. The water collected in a small crater around the spring and the overflow ran a short distance to the north or northwest to a slow-moving stream called Log Bridge Creek. The Clements sampled the naturally-carbonated water and apparently shared volumes of it with friends, family, and neighbors. After a few years, they came to regard the spring as the plantation’s most valuable asset.

Governor Richardson’s second term in office ended in early 1891, and Colonel Clement thereafter considered a change of scenery. Perhaps disheartened by the sharp decline of rice production and the slim profits of stock production, Mr. and Mrs. Clement decided to liquidate their real estate and leave South Carolina. They sold all of Dungannon Plantation for $7,000 (around $2.00 an acre) in January 1892, with one small exception. The Clements retained to themselves “one acre of land near the Wiltown Road [Highway 162] . . . surrounding a mineral spring . . . with the right of ingress and egress to said acre.” This one-acre lot probably represented the northeastern-most corner of the plantation, bounded to the north and west by Log Bridge Creek.[9]

The Clements spent most of the 1890s in Florida, where the young colonel pursued business opportunities related to the booming phosphate industry. For reasons unknown, however, they returned to Charleston around 1899.[10] Subsequent visits to the family’s one-acre lot in St. Paul’s Parish proved that the mineral spring continued to flow without interruption. Neighbors living in proximity to the site informed the Clements that they too had sampled the spring water and found it both refreshing and beneficial.

At the turn of the twentieth century, forty-five-year-old Moultrie Clement realized that a business opportunity was at hand. The nation was awash in advertising for various medicinal waters that purportedly cured every complaint, condition, and disease known to the human race. The most successful of these cure-alls touted their natural attributes, and plain mineral water, with proper marketing and distribution, could generate big profits.

The commercial popularity of bottled mineral water at the turn of the twentieth century was predicated on the scarcity of sanitary running water in the American South. On-demand water taps didn’t appear in downtown Charleston, for example, until 1917, and the surrounding countryside had to wait several more years. A few Charlestonians had access to artesian wells in the city during the 1890s and early 1900s, but most of the local population still drank from traditional wells that yielded unfiltered water that was often contaminated by a myriad of impurities.[11]

The commercial popularity of bottled mineral water at the turn of the twentieth century was predicated on the scarcity of sanitary running water in the American South. On-demand water taps didn’t appear in downtown Charleston, for example, until 1917, and the surrounding countryside had to wait several more years. A few Charlestonians had access to artesian wells in the city during the 1890s and early 1900s, but most of the local population still drank from traditional wells that yielded unfiltered water that was often contaminated by a myriad of impurities.[11]

Colonel Clement must have invested a small fortune in ramping-up a business built around an infinite supply of spring water. He paid at least four scientists to analyze the water, describe its mineral qualities, and provide words of endorsement. He hired laborers to dig a crater around the spring to the depth of seventeen feet below the surface, exposing the phosphate marl rock that had cracked in 1886 and released the spring water. Using the marl as a base, workers built a tall, vertical brick cylinder to channel the water to the surface, and then back-filled the crater around the brick stack. Adjacent to the continuously-flowing well head, now above the surface of the earth, Clement built a “cement receptacle”—probably some sort of concrete basin—to conduct and hold the water so that it could be bottled more easily. To shield all of these features and the water from organic contaminants drifting through the air, Clement erected a “bungalow” of unknown dimensions over the well-head to create a bottling room.[12]

To market his product, Clement needed a unique brand name. According to a later source, the name “Clementia” was proposed by one of the colonel’s friends, Samuel Porcher Stoney (1850–1922), father of Charleston Mayor Thomas Porcher Stoney (1889–1973).[13] Press notices and promotional advertisements for “Clementia Mineral Water” first appeared April 1901 and continued periodically for more than a decade.

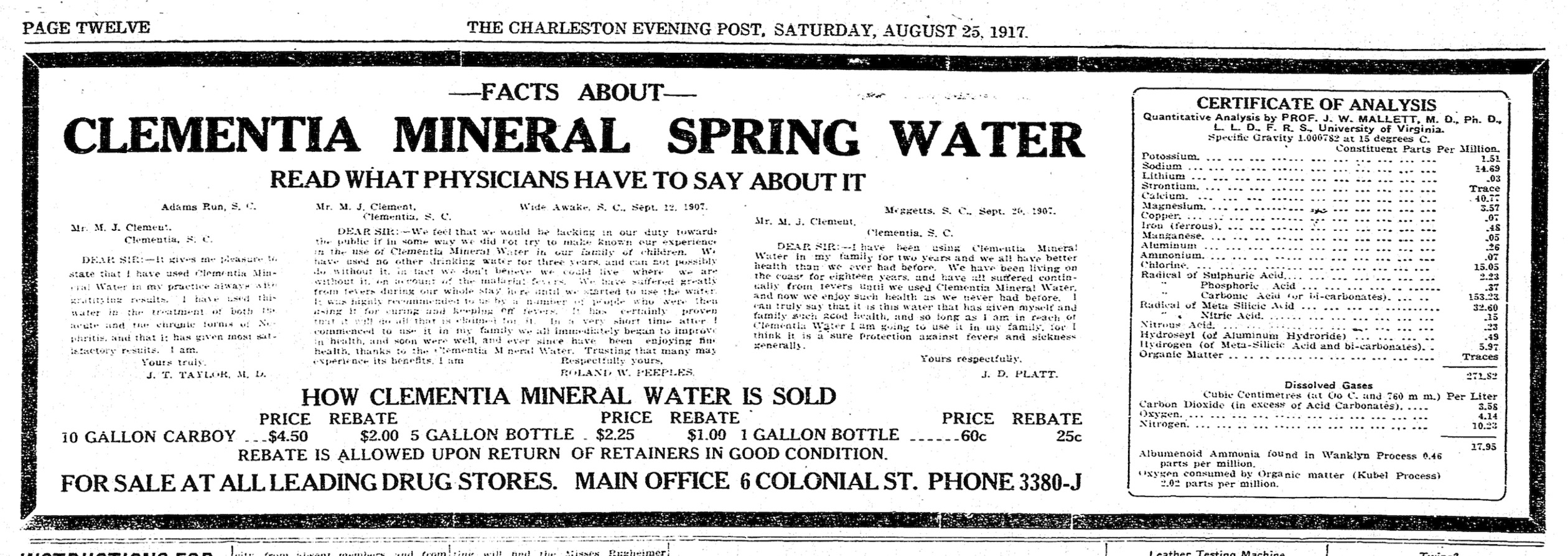

Advertisements for Clementia water extolled the rustic virtues of its origins deep in the phosphate marls of Colleton County. Its association with the destructive earthquake of 1886 connected the water to the power of nature and provided a foil to highlight its restorative properties. Besides being “cool and delicious” and “as clear as crystal,” Clementia mineral water “possessed decided mineral and medicinal qualities.” The proprietor proudly claimed that it was “beneficial in liver and kidney troubles, dyspepsia or chronic indigestion, rheumatism and all troubles arising from malaria.” The water’s mineral properties rendered it suitable “for the treatment of diseases or symptoms of disease of the digestive or urinary organs.” Clementia water was not only “absolutely free from malarial germs” and “perfectly pure and free from surface contamination,” but it was also “a most delightful table water, pleasing to the taste and above all perfectly free from any unwholesome or dangerous impurities.” It was sold in volumes of five, ten, and twelve gallons at various pharmacies in urban Charleston, or in larger quantities directly from Colonel Clement at his downtown address.[14]

Advertisements for Clementia water extolled the rustic virtues of its origins deep in the phosphate marls of Colleton County. Its association with the destructive earthquake of 1886 connected the water to the power of nature and provided a foil to highlight its restorative properties. Besides being “cool and delicious” and “as clear as crystal,” Clementia mineral water “possessed decided mineral and medicinal qualities.” The proprietor proudly claimed that it was “beneficial in liver and kidney troubles, dyspepsia or chronic indigestion, rheumatism and all troubles arising from malaria.” The water’s mineral properties rendered it suitable “for the treatment of diseases or symptoms of disease of the digestive or urinary organs.” Clementia water was not only “absolutely free from malarial germs” and “perfectly pure and free from surface contamination,” but it was also “a most delightful table water, pleasing to the taste and above all perfectly free from any unwholesome or dangerous impurities.” It was sold in volumes of five, ten, and twelve gallons at various pharmacies in urban Charleston, or in larger quantities directly from Colonel Clement at his downtown address.[14]

After the initial burst of advertisements in 1901, Clementia Mineral Water apparently developed a favorable reputation among consumers in the Charleston area. Colonel Clement told reporters that he was distributing larger volumes of the product to customers in Florida, Georgia, and Alabama, but I haven’t yet found confirmation of this claim, which might have simply been marketing bluster. Sales were sufficiently sanguine that the colonel decided to invest his profits to expand the business. In 1905, he purchased sixty-odd acres adjoining the one-acre spring lot that he and his wife retained thirteen years earlier. The new acreage abutted the old Wiltown Road (Highway 162), and was apparently not part of former Dungannon Plantation. Here the Clement family erected a country “cottage” with all the necessary outbuildings for horses, carriages, and so on.[15]

Beginning in April 1905, Moultrie Clement began inviting the public to visit the rural oasis he called “Clementia Mineral Spring” and sample the waters at the source for free. A reporter from the Charleston Evening Post received a tour early that month and described the place in great detail. Turning from the highway onto “a long avenue headed by two giant magnolia trees,” the reporter met the proprietor at his cottage and walked with a group of gentlemen “a short distance” through the pines to the spring. “A faint splashing sound” grew louder as the group approached “the pretty bungalow structure which covers the spring proper.” The reporter was impressed by “the constantly pouring water from the mouth of the spring to the cement receptacle,” and noted that “the settlement [i.e., sediment] in the basin and the suphurous [sic] smell that pervaded the air was proof conclusive to the most dubious mind that all that had been claimed for the water was there in glaring evidence.” The guests drank heartily of the water, then enjoyed a grand lunch with Colonel Clement and napped on the veranda before heading back to the city.[16]

Beginning in April 1905, Moultrie Clement began inviting the public to visit the rural oasis he called “Clementia Mineral Spring” and sample the waters at the source for free. A reporter from the Charleston Evening Post received a tour early that month and described the place in great detail. Turning from the highway onto “a long avenue headed by two giant magnolia trees,” the reporter met the proprietor at his cottage and walked with a group of gentlemen “a short distance” through the pines to the spring. “A faint splashing sound” grew louder as the group approached “the pretty bungalow structure which covers the spring proper.” The reporter was impressed by “the constantly pouring water from the mouth of the spring to the cement receptacle,” and noted that “the settlement [i.e., sediment] in the basin and the suphurous [sic] smell that pervaded the air was proof conclusive to the most dubious mind that all that had been claimed for the water was there in glaring evidence.” The guests drank heartily of the water, then enjoyed a grand lunch with Colonel Clement and napped on the veranda before heading back to the city.[16]

Later in the spring of 1905, Clement advertised directions encouraging customers to avail of public transportation to visit Clementia Mineral Spring. Curious customers could take one of two daily passenger train from Charleston to Rantowles Station (at the modern intersection of Highways 17 and 162), where they would find a carriage to carry them two miles down the road to the spring. Alternatively, visitors could take one of the daily steamboats from Charleston to Wide Awake Landing on the Stono River and find a similar carriage or walk less than a mile to the spring. By August, Clement had hired an agent to promote a greater distribution and perhaps plan the construction of a larger bottling plant at the site. By September, a reporter from the Charleston News and Courier predicted that the colonel was planning “a winter hotel on the place, where, in addition to a enjoying an ideal winter climate, the guests would be able to drink of the waters of the spring, and if so inclined hunt the deer, turkey, partridge and other game upon the great preserves of the neighborhood.”[17]

By the spring of 1906, customers in urban Charleston could order Clementia Mineral Water to be delivered at their doors. It was also “on draught at H. Plenge.” To encourage families to purchase large quantities during the hot summer, Clement advertised that the water “will prevent much sickness, cure stomach disorders, strengthen digestion, regulate the liver, cure kidney and bladder troubles.” Wherever Clementia water was used, he said, there was “no typhoid fever.” Another reporter who visited the spring in September 1907 confirmed that “Col. Clement is arranging to have a suitable hotel erected to hold a much larger number of guests. It will in the near future become a fashionable health resort.”[18]

There was a catch to Clement’s plans for expansion, however. In an effort to fund further construction, he mortgaged his sixty-odd acres for the sum of $2,000. At the same time, he hosted a number of hunting parties at the rural retreat to court potential investors, and invited a battalion of Citadel cadets to camp near the spring.[19] Some sort of construction took place before January of 1909, when the colonel advertised to receive guests at Clementia Mineral Spring for $5 a day or $25 per week. In late 1910, Clement invited guests to reserve accommodations at “Clementia Villa,” where the quiet atmosphere and healthful waters provided “a perfect ecstasy of peace.”[20]

One of Clement’s latest advertisements, in April 1910, sharpened the rhetorical pitch. Describing his product as the premier “Lithia Water” on the market, he boasted that it “will cure all conditions brought about by excess of uric acid in the system.” Of course, you might conclude, the water just ran straight through the body. “Clementia Mineral Water is almost without limit in its benefits,” he claimed. “It is a diuretic, mild, but decided. Its effects on the bowels is more a corrective than an active agent. . . It will stimulate the appetite and greatly aid digestion, and is conducive to quiet sleep.”[21]

One of Clement’s latest advertisements, in April 1910, sharpened the rhetorical pitch. Describing his product as the premier “Lithia Water” on the market, he boasted that it “will cure all conditions brought about by excess of uric acid in the system.” Of course, you might conclude, the water just ran straight through the body. “Clementia Mineral Water is almost without limit in its benefits,” he claimed. “It is a diuretic, mild, but decided. Its effects on the bowels is more a corrective than an active agent. . . It will stimulate the appetite and greatly aid digestion, and is conducive to quiet sleep.”[21]

Colonel Moultrie J. Clement was a rising star in St. Paul’s Parish, which became part of Charleston County in the first decade of the twentieth century. He ran an unsuccessful campaign for political office in 1912, but one year later was elected to represent the county in the South Carolina House of Representatives. The genteel colonel quickly became a popular figure at the capital, but he had a secret.

By the time he took political office in early 1914, Clement had already defaulted on the mortgage of Clementia Mineral Spring. The man to whom he owed money, Henry Gaillard Hall, died in 1913, however, which temporarily prevented any movement toward foreclosure. Mr. Hall’s heirs might have been pressuring Clement two years later. While attending the legislative session in Columbia in January 1916, the sixty-year-old colonel suffered a debilitating stroke. He immediately withdrew to his quiet cottage at Clementia Mineral Spring to recuperate. But no amount of the healing water could mend his financial problems. On the morning of February 12th, Clement put a gun to his head and ended his life.[22]

The heirs of Henry Hall moved to foreclose on the Clementia property shortly after the colonel’s death. The Court of Equity ordered the property to be sold, and it went to public auction in the spring of 1917. A pair of young sisters—Sarah Massenburg and Marion Ebner—purchased sixty-two acres described as “Clementia Mineral Spring Farm,” while the heirs of Moultrie J. Clement retained the land-locked one-acre site surrounding the old mineral spring. In subsequent years, the new owners quarreled with the heirs of Clement over right of ingress and egress across the “farm” to the bubbling spring, and that legal debate stymied the business of marketing the water. The colonel’s son, Boykin Clement, promoted Clementia Mineral Water as late as 1932, but eventually conceded defeat and sold the spring.[23]

The heirs of Henry Hall moved to foreclose on the Clementia property shortly after the colonel’s death. The Court of Equity ordered the property to be sold, and it went to public auction in the spring of 1917. A pair of young sisters—Sarah Massenburg and Marion Ebner—purchased sixty-two acres described as “Clementia Mineral Spring Farm,” while the heirs of Moultrie J. Clement retained the land-locked one-acre site surrounding the old mineral spring. In subsequent years, the new owners quarreled with the heirs of Clement over right of ingress and egress across the “farm” to the bubbling spring, and that legal debate stymied the business of marketing the water. The colonel’s son, Boykin Clement, promoted Clementia Mineral Water as late as 1932, but eventually conceded defeat and sold the spring.[23]

The end of the mineral water business in the 1930s did not spell the end of the Clementia name, however. During the early 1920s, the families who purchased Colonel Clement’s sixty-two acre “farm” and resided there applied the brand name to a new business venture. The increasing volume of automobile traffic along highways 17 and 162 inspired them to construct several commercial buildings along the acreage closest to the old Wiltown Road. By the mid-1920s, the site hosted a general store, coffee shop, and filling station, advertised collectively as “Clementia Stores.”[24]

In October 1929, local newspapers announced the recent completion of a new “tourist camp” at “Clementia Springs.” This venture to provide tourist accommodations was the work of Joseph W. Ebner, the husband of Marion who purchased the Clementia “farm” in 1917. Mr. Ebner initially built six or seven brick-veneer cabins, two-bedroom structures with electricity, private baths, and running water. “Clementia Cabins,” as they became known, proved to be “very popular with tourists,” despite the onset of the Great Depression. Encouraged by increasing traffic, Mr. Ebner continued to build. In November 1930, he announced the grand opening of “Clementia Dining and Dancing Room,” where customers could enjoy a meal and the musical stylings of the “Clementia Snappy String Orchestra.” By the spring of 1931, Mr. Ebner had constructed a total of twenty-one cabins and other improvements to the tourist site unofficially known as Clementia Village.[25]

One might wonder why rural Clementia, fourteen miles from downtown Charleston, proved such a popular attraction during the Great Depression and the era of Prohibition in the United States (1920–33). The answer likely had something to do with Joseph Ebner’s business connections. He was convicted of bootlegging in the late 1920s, was involved in two shootings at Clementia in 1931 and 1932, hosted illegal slot machines at his club, and was arrested in 1934 while driving a mobile “arsenal” in Virginia and accused of “hi-jacking bootleg whiskey” in that state.[26] In short, it appears that the Clementia Tourist Camp, as it was most commonly called in the early 1930s, was a raucous blind tiger—a legitimate business hosting illegal activity.

In the weeks after Joseph Ebner’s arrest on weapons charges in the autumn of 1934, the popular Clementia night club briefly changed its name to “The Jockey Club.”[27] Ebner also invested in a motel called “Club Folly” at Folly Beach in June 1935, but was soon arrested for operating a disorderly house (that is, hosting loud music and dancing after midnight on a Sunday morning). Ebner’s virtuous wife, Marion, informed the press that her husband was no longer affiliated with the tourist cabins at Clementia Village, and his commercial career ended.[28] After a young married woman committed suicide in the company of Joe Ebner in 1937, his name disappeared from local newspapers. He withdrew to his house at Clementia and followed the example of Colonel Clement nearly forty years earlier. In March 1955, he put a gun to his head and ended his life.[29]

In the weeks after Joseph Ebner’s arrest on weapons charges in the autumn of 1934, the popular Clementia night club briefly changed its name to “The Jockey Club.”[27] Ebner also invested in a motel called “Club Folly” at Folly Beach in June 1935, but was soon arrested for operating a disorderly house (that is, hosting loud music and dancing after midnight on a Sunday morning). Ebner’s virtuous wife, Marion, informed the press that her husband was no longer affiliated with the tourist cabins at Clementia Village, and his commercial career ended.[28] After a young married woman committed suicide in the company of Joe Ebner in 1937, his name disappeared from local newspapers. He withdrew to his house at Clementia and followed the example of Colonel Clement nearly forty years earlier. In March 1955, he put a gun to his head and ended his life.[29]

From the late 1930s onward, the Ebner sons continued to operate the declining operations at Clementia Motor Court. The ten-acre site, which included a total of thirty cabins and apartments, a café, store, laundry, filling station, and one large residence, underwent a major renovation in 1949, but its best days were in the past.[30] Long-term renters replaced tourists in what became known as Clementia Apartments. Family members also operated Clementia Antiques and Clementia Nursery at the site during the second half of the twentieth century, which some local residents might still remember. By the late 1970s, the old cabins were converted into seasonal housing for migrant workers toiling on nearby farms, and they were gone by the end of the century.[31]

The “two giant magnolia trees” described by a visitor in 1905 still flank the private driveway next to the modern sign for Clementia Village on Highway 162. The bubbling mineral spring first observed in 1886 might still flow somewhere on the property within, but few residents of modern Hollywood Township remember the rise and fall of the commercial venture that inspired the name. Clementia is not the site of a forgotten ghost town, but some might conclude that its history includes more than a few ghosts.

[1] Long-time CCPL employee Dot Glover once resided near Clementia and provided invaluable assistance to this research project. Thanks, Dot!

[2] Writers’ Program (U.S.), South Carolina, Palmetto Place Names (Columbia, S.C.: The Sloane Printing Co., 1941), 35.

[3] See the Joseph D. Taylor papers at the South Carolina Historical Society, collection No. 525.

[4] Charleston News and Courier, 26 August 1885, page 3, “The Cyclone and the Crops,” described M. J. Clement as “one of the largest and most successful rice planters on Pon-Pon” and an authority on rice cultivation in the area.

[5] Otto W. Nuttli, et al., The 1886 Charleston, South Carolina, Earthquake—A 1986 Perspective. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 985 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1986), 9–12.

[6] Various twentieth-century sources state that Clement discovered the spring either one, four, or six days after the earthquake; see, for example, Charleston News and Courier, 14 April 1901, page 16, “Nature’s Own Remedy”; Charleston Evening Post, 27 April 1901, page 2, “An Earthquake Spring”; News and Courier, 23 August 1905, page 4, “Special Notices”; News and Courier, 17 September 1905, page 5, “A Fine Mineral Spring”; undated (1932) pamphlet for “Clementia Mineral Springs Company” in Thomas P. Stoney Papers, South Carolina Historical Society (hereafter SCHS), 100/48/04.

[7] For Clement’s staff role as Commissary General, see News and Courier, 25 January 1887, page 1; News and Courier, 25 April 1889, page 1.

[8] Clement worked with Theodore Dehon Jervey in Charleston to manage his ranching efforts; see the finding aid for Theodore Dehon Jervey Family papers, 1869–1947, SCHS 1257. Clement advertised to sell milk cows, calves, and sheep in News and Courier, 6 June 1887, page 3.

[9] Lucia Clement to Samuel G. Fitzsimons, 2 January 1892, Charleston County Register of Deeds Office (hereafter CCRD), K27: 135–37.

[10] In a 1932 summary history of the “Estate of Lucia T. Clement,” Thomas Porcher Stoney (1889–1973) stated that Clement sold Dungannon and “then moved to Florida and engaged in the phosphate mining business.” See Thomas P. Stoney Papers, SCHS, 100/48/04. In News and Courier, 27 September 1899, page 3, Clement advertised his desired to rent a furnished house in Charleston.

[11] For an overview of local water-delivery history, see the website of Charleston Water System: https://www.charlestonwater.com/163/Water-System.

[12] These features are described in News and Courier, 17 September 1905, page 5, “A Fine Mineral Spring”; News and Courier, 25 September 1907, page 5, “At Clementia Springs”; Evening Post, 8 April 1905, page 2, “Clementia Springs Visited.”

[13] In a 1932 summary history of the Clementia business, Thomas Porcher Stoney (1889–1973) stated that the name was suggested to Mr. Clement “by a friend Mr. Porcher Stoney.” This obscure anecdote is almost certainly a reference to T. P. Stoney’s father, Samuel Porcher Stoney, who was commonly called S. Porcher Stoney at the turn of the twentieth century. See Thomas P. Stoney Papers, SCHS, 100/48/04.

[14] News and Courier, 14 April 1901, page 16, “Nature’s Own Remedy”; Evening Post, 27 April 1901, page 2, “An Earthquake Spring”; News and Courier, 27 April 1901, page 4, “Clementia Mineral Water”; News and Courier, 30 August 1901, page 4, “Persons affected with liver, kidney or bladder troubles”; News and Courier, 28 September 1901, page 4, “Clementia.”

[15] Clement’s 1905 purchase of sixty-five acres is mentioned in the aforementioned 1932 summary history of the “Estate of Lucia T. Clement.” The property was still in Colleton County at that time, and I have not yet visited that county’s deed office to confirm the details of Clement’s purchase.

[16] Evening Post, 8 April 1905, page 2, “Clementia Springs Visited.”

[17] Evening Post, 26 April 1905, page 4, “Clementia Mineral Spring”; News and Courier, 17 September 1905, page 5, “A Fine Mineral Spring.”

[18] News and Courier, 6 February 1906, page 6, “ ‘No Typhoid Fever’; News and Courier, 29 April 1906, page 2, “Clementia Mineral Water”; News and Courier, 10 June 1906, page 9, “Clementia Mineral Water”; News and Courier, 25 September 1907, page 5, “At Clementia Springs.”

[19] For example of hunt parties, see the “Society” news in Evening Post, 20 October 1909, page 5; Evening Post, 27 December 1911, page 2; News and Courier, 2 April 1908, page 8, “Cadets at Clementia Springs.”

[20] News and Courier, 1 January 1909, page 3, “Advice to Those with Ailments”; News and Courier, 13 November 1910, page 4, “Come to Clementia Mineral Spring.”

[21] News and Courier, 17 April 1910, page 4, “Lithia Water.”

[22] Clement’s debt to Hall is described in the aforementioned 1932 summary history of the “Estate of Lucia T. Clement.”; News and Courier, 13 February 1916, page 12, “Moultrie J. Clement Dead. Shoots Himself in Right Temple at Clementia Springs.”

[23] A summary of the property’s sale in 1917 and subsequent tension between the Massenburgs, Ebners, and Clements can be found in the Thomas P. Stoney Papers at SCHS, 100/48/04. See Master in Equity F. K. Myer to Robert S. Myer, 1 May 1917, CCRD I28: 86; Robert S. Myer to Sarah Emerson Massenburg and Marion Emerson Ebner, 30 June 1917, CCRD Y27: 290.

[24] See the advertisement for Proctor & Gamble soap in News and Courier, 13 February 1926, page 12; Evening Post, 14 January 1927, page 15, “Open Until Midnight.”

[25] News and Courier, 25 October 1929, page 2: “Ebner Completes Tourists’ Camp”; News and Courier, 23 November 1930, page 10: “Grand Opening”; Evening Post, 25 November 1930, page 14: “Clementia Camp Dining Pavilion.”

[26] Ebner’s arrest, conviction, and sentencing for conspiracy to evade prohibition laws in 1925–26 was well-documented. He reportedly told undercover agents that “he could camouflage as much as 300 cases [of illegal whiskey] because he had a farm in the country”; see Evening Post, 1 April 1925 (Wednesday), page 2, “Round Up Is Followed by 4 Hearings”; News and Courier, 3 April 1925, page 10, “Alleged Liquor Handlers Held”; News and Courier, 27 May 1926, page 2, “Found Guilty of Conspiracy”; News and Courier, 5 June 1926, page 1, “Liquor Dealers Are Sentenced”; News and Courier, 29 October 1931, page 1, “Farmer is Shot in Land Quarrel”; News and Courier, 2 December 1931, page 14: “Continue Campaign on Illegal Slot Machines”; News and Courier, 8 September 1932, page 2, “Soldier Is Shot at Tourist Camp”; News and Courier, 1 August 1934, page 10, “Trio From Here Held In Virginia.”

[27] “The Jockey Club (formerly Club Clementia)” opened on 20 October 1934 and operated under that name through at least May 1935; see advertisements in Evening Post, 19 October 1934, page 10-B; Evening Post, 11 May 1935, page 8-A.

[28] “Club Folly (formerly Rest Haven)” opened on 1 June 1935; Ebner was arrested on 23 June; see advertisement in News and Courier, 1 June 1935, page 6; News and Courier, 27 June 1935, page 9, “Ebner Hearing Today”; News and Courier, 29 June 1935, page 2, “Ebner Forfeits Bond.” Ebner identified himself as the “sponsor” of Club Folly in a “Notice” published in Evening Post, 29 June 1935, page 2, informing the public that “according to the laws of Folly Island, the playing of music or dancing after midnight Saturday constitutes a disorderly house.”

[29] The woman in question was Hazel Wyndham Wichmann, wife of August F. Wichmann; see News and Courier, 5 June 1937, page 8, “Woman Ends Life With Poison Dose”; News and Courier, 2 March 1955, page 9, “Joseph W. Ebner Is Found Dead at Residence”; News and Courier, 3 March 1955, page 15, “Joseph W. Ebner.”

[30] Evening Post, 21 May 1949, page 12, “We Offer for sale Clementia Motor Court”; Evening Post, 29 June 1949, page 12, “Clementia Cabins.”

[31] Evening Post, 27 April 1977, page 2, “Housing, Child Care are Major Migrant Problems.”

NEXT: Charleston's Second Ice Age: Rise of the Machines

PREVIOUSLY: The Charleston Tar-and-Feathers Incident of 1775

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments