Charleston's First Market and Place of Public Humiliation

Processing Request

Processing Request

Following the precedent of “market towns” in England, the founders of Charleston created a public marketplace with stalls for the sale of meat, fish, and produce, as well as a cage, stocks, and pillory to punish miscreants in public view. The town plan of 1672 reserved a prominent central space for such purposes, but a number of factors induced early residents to shop elsewhere. Prior to 1735, the clamor and smells of Charleston’s daily market emanated from a forgotten site at the east end of Broad Street, near the Cooper River waterfront.

Most residents and visitors think of the City Market in Market Street as one of Charleston’s most historic institutions. Reserved for market purposes in 1788 and used continuously since the first of August, 1807, Market Street and its mid-nineteenth-century brick sheds represent a significant chapter in the cultural history of the Palmetto City.[1] Prior to 1807, however, generations of Charlestonians purchased ingredients for their daily meals at a succession of officially-designated public marketplaces scattered across the urban landscape. A perusal of various eighteenth-century documents and maps yields valuable evidence of earlier market sheds standing at the east end of Tradd Street, the east end of Queen Street, the south end of King Street, and at the present site of City Hall at the northeast corner of Meeting and Broad Streets.[2] But none of these sites represents the earliest marketplace in the colonial capital of South Carolina. To identify the site of Charleston’s earliest food sales, we have to delve into the incomplete records of the colony’s Proprietary Era.[3]

The sparse, surviving records of the first twenty-one years of European settlement in South Carolina, 1670 through 1691, contain few details about daily life in the colony. Following a reorganization of the provincial government in the summer of 1692, however, the volume of surviving records increases and details of daily life in Charleston slowly begin to emerge. Local planters, fisherfolk, drovers, and butchers fueled the vending of perishable food in the capital, but their private enterprise unfolded within a cultural and legal framework crafted by centuries of English precedent. Charleston was created in the mold of a traditional “market town,” an urban settlement surrounding a communal marketplace regulated by local law. As I described in Episode No. 56, however, colonial-era Charles Town lacked a municipal government before its incorporation in 1783. Prior to that time, the provincial legislature adopted laws and resolutions to superintend the urban capital.

The extant public records of Proprietary South Carolina contain scattered clues that reveal the location of the town’s early market and provide evidence of the continuity of English traditions. The earliest evidence of public food sales in urban Charleston, for example, overlaps with descriptions of early law enforcement and criminal justice within the town. While the pairing of grocery shopping and corporal punishment might seem like an unappetizing combination, these activities were once familiar companions. In market towns across Europe and throughout the American colonies during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, marketplaces frequently hosted both food sales and various forms of physical chastisement. The goal was to encourage civil harmony within a community by punishing petty crimes at a site of maximum public exposure to ensure maximum personal humiliation. Because every family within a given community had to go to the market to purchase ingredients for their daily meals, everyone witnessed the shame of their neighbors’ misbehavior.

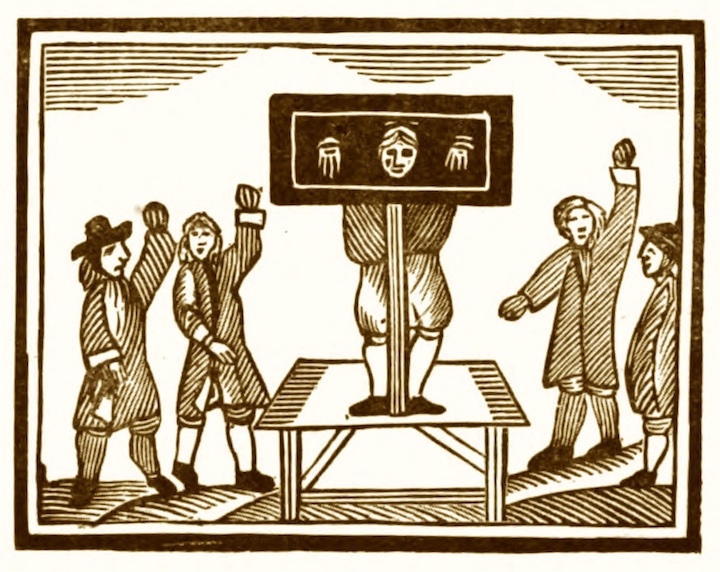

The three most common forms of corporal punishment for petty offences during this era involved the use of hand-made implements known as the pillory, stocks, and cage. A pillory is an upright wooden frame, secured firmly to the ground, used to restrain the neck and wrists of a standing person. A set of stocks is a similar wooden frame placed lower to the ground to restrain the ankles of a person sitting on his or her rear end. These two familiar implements were used to punish petty, non-violent infractions. According to an English author writing at the beginning of the eighteenth century, “the pillory is properly used for cheats, perjurers, libellers, and blasphemers; and the stocks, for vagrant, idle fellows, who can give no good account of themselves.”[4] Because these devices were traditionally located in proximity to marketplaces, it was not unusual for shoppers to hurl fruit and vegetables at their neighbors who happened to be standing in the pillory or sitting in the stocks.

While the pillory and stocks were used to punish individuals who had been convicted of an offense, the cage was a device used for the temporary incarceration of an individual immediately after his or her arrest. In contrast to the more familiar jail cell located within a larger structure, the cage was typically an outdoor enclosure, open to public view, designed to hold and humiliate persons found on an urban street during the hours when streetwalking was prohibited. The individuals placed in such a cage might be women or enslaved people caught on the streets after sundown, or someone stretching their legs at a time when the law required their attendance at divine service. At least three types of cages were used in Europe and America during the seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries. One variety used iron bars to form one, two, or three walls that were attached to the exterior of a larger masonry structure. Other cages were free-standing and/or portable structures made entirely of iron bars. A third variety was sometimes called a “back grate” because its low, narrow shape purposefully prevented the person incarcerated within from either sitting down or standing upright.[5]

The original town plan of Charleston, the so-called Grand Model of 1672 that I described in Episode No. 245, included a reservation for a public square of two-and-a-half acres at the center of the town. That site, now identified as the intersection of Broad and Meeting Streets, was described in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries as “Market Square,” or the site reserved for a “market place.” Despite that civic designation, the early inhabitants of Charleston did not utilize the central marketplace for many decades.[6] Most of the town’s early population settled along the eastern waterfront, near the Cooper River, ranging from Tradd Street on the south to Queen Street on the north. For the first half-century of the town’s life, cultural and economic activity in urban Charleston revolved around a spot of ground at the east end of Broad Street, now occupied by the Old Exchange Building. This was the site of the town’s first public market at the place of public punishment, but evidence to confirm this theory is scattered over thirty years’ worth of archival records.

The earliest-known clue to this site appears on a hand-drawn map of Charleston created in 1686 by Jean Boyd, a French Huguenot immigrant who had recently arrived in South Carolina. If you look closely at Boyd’s map, which I discussed Episode No. 98, you’ll see a capital letter “A” next to a small gallows at the east end of Broad Street, adjacent to the Cooper River. Boyd’s caption identifies letter “A” as the site of a fort and “lieu de justice,” or “place of justice.” Another early clue points to the same site in the year 1687, at which time “a certain cage” was said to be standing “over against” (that is, opposite) to the southern boundary of Grand Model Lot No. 14, which occupied the northwest corner of Broad and East Bay Streets.[7] In other words, the town cage of late-seventeenth-century Charleston was standing in the middle of Broad Street, near East Bay Street. As in contemporary England and other communities across Colonial America, the presence of the public cage at this site implies the presence of market activity nearby.

South Carolina’s General Assembly ratified a temporary act “to appoint a Market Place in Charles Town” in October 1692, but the text of this landmark law disappeared shortly after it expired in 1694.[8] Owing to this archival loss, we have to use our imaginations to produce an image of the activity it regulated. The designated marketplace of 1692 was almost certainly located at the east end of Broad Street, along the waterfront “wharf” that became known as East Bay Street (see Episode No 180). Because the provincial treasury was quite small at that moment, it seems unlikely that the legislature ordered the construction of a market shed or any sort of semi-permanent infrastructure. Market vendors might have built their own portable stalls to sell their wares, and perhaps erected canvas awnings for temporary shade. Canoes and boats carrying fresh seafood and plantation produce might have docked at the foot of the marketplace and bartered with customers standing on shore. The lost text of the 1692 law probably dictated the hours of the daily market and identified the types of fruit, vegetables, fish, and meat eligible for sale at the site. Despite the expiration of its legal charter in 1694, Charleston’s daily food market probably continued, more or less informally, for several subsequent years. The legislature, having established a community marketplace by local custom and legal mandate, might have simply expected the institution to continue without further government oversight.

Practices at the food market likely evolved during the final years of the seventeenth century as a series of civic projects reshaped the landscape at the east end of Broad Street. In 1694, for example, South Carolina’s provincial government began planning the construction of a brick seawall to protect the east side of what became East Bay Street. That project finally commenced in 1696, at which time the legislature proposed to enclose the intersection of Broad and East Bay Streets within a large fortification. The proposed fort was moved elsewhere in 1697, however, clearing the path for other developments at the east end of Broad Street. A 1698 plan to build a brick Watch House at this site to house Charleston’s nocturnal police force was revised in 1701 and completed in 1702. That same year, workers completed a brick Half-Moon Battery that outlined the intersection of Broad and East Bay Streets for successive generations.[9]

The maturation of these building projects probably disrupted the business of food sales in Charleston at the turn of the eighteenth century, but the provincial government took steps to facilitate market activity near the east end of Broad Street. In January 1700, for example, while bricklayers were constructing a “wharf wall” along the east side of the street, the South Carolina legislature officially reserved a broad strip of land at the east end of Broad Street as a public landing place for small boats.[10] In November of 1700, the Commons House of Assembly ordered two of its members to draft a bill to nominate a “clerke of ye market” to regulate the sales of provisions in the capital, though the assignment produced no results.[11] In the early weeks of 1701, the Commons House ordered the provincial treasurer to pay carpenter Edward Loughton “the sume of eight [Spanish] dollers for making & setting up the stocks in Charles Town.”[12] The location of Mr. Loughton’s handiwork was not specified at that time, but the new stocks were almost certainly adjacent to the newly-constructed Watch House standing at the intersection of Broad and East Bay Streets. During construction of a Half-Moon Battery to surround three sides of the Watch House, the legislature in August 1701 reserved an area measuring twenty feet wide on both the north and south sides of that fortification for use as public landings.[13] The substantial brick remnants of that curving brick structure are still visible in the basement or dungeon of the Old Exchange Building, allowing visitors to visualize the daily landing of boats and canoes delivering seafood and country produce to the people of urban Charleston.

During the early years of Queen Anne’s War between Britain, Spain, and France, which commenced in 1702, concerns for the defense of urban Charleston focused on strengthening the town’s Cooper River waterfront. Most of the community’s residents and commerce were clustered along this eastern perimeter, but fear of a ground assault from the western Ashley River induced the provincial government in late 1703 to order the construction of a fortified wall and moat to encircle the town of some two thousand souls. The entrenchments erected in 1704, which I described in Episode No. 230, dug through the center of the “Market Square” reserved in the Grand Model of 1672, but that work did not disrupt the town’s market activity. The vending of fresh food had clung to the Cooper River waterfront since the earliest days of the town and became increasing mobile during the first decade of the eighteenth century.

In October 1704, Governor Nathaniel Johnson recommended that the provincial legislature consider “the making of an act for the settling of a market in Charlestown and to prevent forestalling and engrossing by the hucksters, and other ill-disposed persons.”[14] After the elected assembly ignored the suggestion, Johnson revisited the topic in the spring of 1706 with a litany of complaints about various “civil affairs,” including the unregulated sale of foodstuff like bread, fruits, vegetables, and meat in Charleston. There were two main problems, said the governor. The first he described as “forestalling,” in which a small number of agents would monopolize the purchase of wholesale goods as they came to town in canoes or carts, and then retail them to customers on the street with a considerable price mark-up. The second problem was “unreasonable hucstering,” in which people were crying or hawking food items as they passed through the streets with baskets and/or push carts (see Episode No. 158). Complaints about these two issues continued for many generations beyond Governor Johnson’s administration, and they were usually leveled at enslaved vendors who were trying to make a bit of extra money for themselves. In March 1706, the South Carolina legislature responded to the governor’s complaints by drafting and considering a bill “to prevent huckstering and forestalling and for haveing a markett in Charles Town and for appointing a fair.” The legislature never ratified the bill, however, and the lack of an officially-designated marketplace continued for several more years.[15]

Finally, on 8 April 1710, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified “An Act to appoint and erect a Market in Charles Town, for the Publick sale of Provisions, and against Regrators, Forestallers and Ingrossers.”[16] The text of this important act, which has never been published, confirms the location of the town’s food market at the east end of Broad Street. “For want of a publick market in Charles Town, the chief place of trade and the greatest resort of any in this province,” said the preamble, “dead victuals and provisions are sold at very great and extravagent rates and prices in the said town, not only to the great oppression of the inhabitants of the province[,] but to the discouragement of merchants and other strangers trading from and to the same, who to carry on their trade are obliged to live and reside in the said town.” Furthermore, the text continued, “the want of such a market in Charles Town has given such encouragement to sundry evil disposed and covetous persons as to incite them to put in practice the most abominable and scandalous projects of huckstering forestalling and ingrossing.” To rectify the situation, the provincial General Assembly enacted the following choice text:

“All persons whatsoever, inhabitants of this province, who shall after the first day of May next bring or send, or cause to be brought or sent to Charles Town, either by land or water, any fresh butter, cheese, dead or live sheep, lambs, calves, swine, or any pigs, geese, capons, hens, chickens, pigeons, poultry, eggs, wild or tame fowles, fresh fish and all sorts of roots, herbs and fruits or other dead victuals whatsoever (salt pork and beef, and butter in barrels, corn or grain excepted) to be sold and disposed of shall[,] before he, she or they bargain, contract, agree, sell or dispose of the same or any [of] the before mentioned dead victuals or provisions[,] bring the same to the Publick Market in Charles Town, which is hereby declared enacted and appointed to be held every day in the week (except Sundays) at or near the Watch House in Charles Town at the end of the Broad als Cooper Street.”

The market act of 1710 appointed a clerk, Edward Hakes, to superintend the daily market, “to search, view, and examine all such dead victuals and provisions aforesaid, and to prevent the sale of any corrupt or unwholesome victuals and provisions by burning or otherwise.”[17] The clerk was also obliged to ring a bell suspended above the Watch House to give “due notice . . . of the time when such victuals and provisions are to be sold, and the Market open’d.” The bell sounded at 6 a.m. during the months of March through August, then at 7 a.m. during September through February. The daily market opened “immediately after the ringing of the said bell at the respective times aforesaid,” after which the inhabitant were “allowed to buy, barter, and sell live and dead victuals and provisions as aforesaid.”[18] Persons who attempted to sell any of the prescribed goods at any place outside the designated market, or who attempted to trade before the ringing of the market bell, would forfeit the goods in question to the clerk.[19] Although the act did not specify the hour at which the market closed, all later iterations of market law in Charleston ordered the site to be cleared before sundown. Local vultures probably formed a volunteer clean-up crew, as they routinely did at Charleston’s marketplaces until the 1920s (see Episode No. 25 and No. 26).

While the market act of 1710 specified the location of the Charleston’s food market, the text did not mention the construction of any market structure or any associated implements of public humiliation. Despite these omissions, several later documents confirm the presence of several structures arrayed along the center line of Broad Street, standing slightly to the west of the Watch House. Pedestrians, animals, and vehicles traversing along Broad Street and through its intersection with East Bay were obliged to pass around and through the site, which was undoubtedly thronged with vendors and customers both Black and White during the early hours of each day.

The cage, stocks, and pillory might have stood near the east end of the market, near the west façade of the Watch House and under the gaze of the town’s nocturnal police force. The iron cage was apparently out of service in mid-September 1721, at which time the South Carolina Commons House ordered the public treasurer to immediately “put the Watch House and the publick cage in Charles Town in repair.”[20] Later that same day, the provincial legislature ratified a law to strengthen the nocturnal police force or Night Watch in urban Charleston. The text of the law specifically addressed the use of the cage: “And in case any Negro’s be found out of their masters houses after nine of the clock in the evening & can’t give such good account of themselves as the comanders of the Watch for ye night shall be satisfied with, then such Negro shall be apprehended and confined in the cage of Charles Town till the next morning & then to carry him before some Justice of the Peace to be examined[,] which said Justice of the Peace is hereby impowered to order the said Negro such punishment as he shall think the nature of the offence shall require.”[21] Similar instructions for confining enslaved streetwalkers in the town cage appear in subsequent revisions of urban police laws through the remainder of the eighteenth century.

A few yards to the west of the cage and other implements of humiliation stood a wooden shed or “shambles” used to display butchered meat hanging from iron hooks. A valuable reference to this structure survives in the text of a court case adjudicated in the autumn of 1729. Captain Edward Vanvelsen, watch commander on the evening of September 12th, testified a few days later about an argument he witnessed that evening. Vanvelsen was among a group of men relaxing at the Watch House, perhaps seated on benches just outside its western door, when one of the party, described as a “seafaring man,” “got up & went under one of the butchers shambles.” There, perhaps just a few yards from the Watch House, the mariner turned back and began cursing at the seated men.[22] To the west of the butchers’ shambles likely stood one or more similar wooden sheds, probably fitted with horizontal stall boards for vending fresh fish and country produce to customers on foot.

The market act of 1710, like its predecessor ratified in 1692, was designed to be in force for just two years. Through various legislative acts, however, it continued in force for more than a decade.[23] Responsibility for the management of Charleston’s marketplace then devolved to a new political entity in 1722. In June of that year, Governor Francis Nicholson convinced the South Carolina General Assembly to ratify an act transforming the humble “market town” known as Charles Town into the municipality known as Charles City and Port. The newly-incorporated City Council thereafter assumed responsibility for the market structures standing near the east end of Broad Street, but their jurisdiction was short-lived. Charles City and Port reverted to unincorporated Charles Town in October 1723, per legal instructions from London, after which time the public market endured several years of government neglect and decline.[24]

Perhaps the most evocative evidence of Charleston’s first market appears in a legislative conversation that took place in the spring of 1725. Governor Nicholson, though frustrated in his various efforts to improve urban Charleston, was then guiding plans for the renovation of the Watch House at the east end of Broad Street. Rather than add a story above the aging edifice for the storage of muskets, swords, and other small arms, the South Carolina legislature resolved to demolish the existing building and erect a larger structure in its place to serve as both a police headquarters and an armory. In late March 1725, Governor Nicholson offered some advice to improve the appearance of the proposed public edifice and Charleston’s principal thoroughfare. He recommended “that the old Market house [in the middle of Broad Street] be removed & part of it for butchers be put on one side of the said armory & that for the fish &ca on the other side & that the pillory stocks cage &ca be put in some more proper place & all other obstructions to the prospect of the street removed & some method taken for the more cleanly keeping the said street.”[25]

The assembly appointed a joint legislative committee to discuss the governor’s recommendation, but their slow progress displeased the colonial executive. In early April 1725, as Nicholson prepared to depart South Carolina for good, he reiterated his suggestion “that the old market, a com’on nusance to the Broad Street be pulld down, and a new market for flesh [that is, meat] be built on one side of the watch house and another for the fish on the other side to range with it . . . and that the cage pillory and stocks be removed to some other & more proper place.”[26]

The aforementioned references demonstrate that the marketplace in eastern Broad Street—authorized by law in 1710 and maintained throughout the 1720s—stood more than one thousand feet to the east of the central Market Square reserved in the Grand Model of 1672. Governor Nicholson did not recommend moving the market to the public land at the intersection of Broad and Meeting Streets in 1725 because that central site was still encumbered by the old drawbridges and fortifications erected in 1704 to protect the western entrance to the town. The relevance of those obstructions was quickly fading in the spring of 1728 when the new Watch House at the east end of Broad Street was finally completed.[27] That March, nearly three years after the departure of Governor Nicholson, South Carolina’s provincial government resolved to direct the builders of the new Watch House “to remove the present market to that part of the town near where the Old Church stood [that is, the original site of St. Philip’s Church, now occupied by St. Michael’s Church], which was laid out purposely for that use, and . . . to erect a new Market House in the said place, with such proper stalls and conveniencies as they shall think proper.”[28]

One month later, the Commons House briefly considered “a bill for removing the present Market House in Charles Town and for appointing erecting keeping and governing a New Market in the said Town for the publick sale of provisions.” The proposed changes were abandoned, however, because South Carolina’s provincial government lapsed into a state of political dysfunction in 1728 that persisted for three more years.[29]

The final chapter in the saga of Charleston’s first marketplace commenced with the advent of robust royal administration of South Carolina in 1731. Two years after that important political change, the provincial General Assembly read two petitions in the spring of 1733 submitted by two different groups of local residents. The first complained of “the inconvenience of the market in Charles Town near the Watch House and praying that the same might be removed to the publick square of the said town.”[30] The second petition asked “that the market may be removed to Mr. Wm. Elliots Bridge”—that is, to a waterfront location southeast of customary location. The Commons House approved both suggestions and directed a committee to “bring in a clause to establish two markets agreeable to the prayer of the two petitions.”[31] The map published in London in 1739 with the title The Ichnography of Charles-Town depicts the two markets requested in 1733, labeled “The New Market” at the northeast corner of Broad and Meeting Streets, and “The Bay Markets” on a wharf at the east end of Elliott Street.

The two new markets depicted in 1739 were not built immediately after they were requested, however. The removal of the older market structures from the east end of Broad Street and the construction of new facilities elsewhere required public funds and political will. In February 1734, for example, Governor Robert Johnson reported that workmen examining “the cage and stocks belonging to this town” opined that the aging structures were not worth repairing and had to be built anew for the new market site in the center of Charleston.[32] The intersection of Broad and Meeting Streets had been encumbered with earthworks, moats, and fortified drawbridges since 1704, but the last remnants of those structures disappeared during the early days of Governor Johnson’s royal administration. No details of that work survive, but the site had to be cleared and leveled before the construction of new market facilities could commence.

South Carolina’s first newspaper, the South Carolina Gazette, commenced publication in January 1732, and references to Charleston’s new marketplace began to appear in 1735. In May of that year, for example, Mr. Birot at “the sign of the white horse” advertised a house for rent “in Broad-street near the New-Market.” Six months later, however, Edward Clark advertised to teach “reading, writing and arithmetick” at a house “near the new intended Market.”[33] Confirmation of a functioning market at the northeast corner of Broad and Meeting Streets—the present site of City Hall—appeared in early 1736. When William Linthwaite mortgaged a small lot near the corner of King Street that January, he noted that the property bounded to the south on Broad Street, “wherein the Market is now kept.”[34]

The establishment of a public market at a site designated for that purpose in 1672 did not generate fanfare and celebration, but it represented a significant milestone in the civil history of Charleston. The removal of the old market facilities near the east end of Broad Street obliterated vestiges of the town’s infancy and opened the vista familiar to residents and visitors of the past three centuries. As the people of Charleston continued their daily labors beyond the 1730s, memory of the town’s earliest market quietly faded. The new facility in Market Square soon became known as the “Beef Market,” while the vending of smaller animals, country produce, and seafood continued at satellite facilities on the Cooper River waterfront for the remainder of the eighteenth century. The South Carolina Gazette occasionally published descriptions of men and women sitting in the stocks or standing in the pillory at Market Square, but those ancient practices declined at the turn of the nineteenth century as new ideas about criminal justice reshaped the world of law enforcement.

The story of Charleston’s earliest marketplace represents an important module in a larger narrative about the creation of the community we inhabit today. Rooted in English traditions, the market anchored the clamor of daily life at the east end of Broad Street in the late seventeenth century and endured half a century of dramatic changes within the nascent town. Swept away by the march of civic progress in the early 1730s, the structures and practices cultivated in Charleston’s first market formed a precedent for subsequent facilities scattered across the expanding landscape, including the surviving market sheds in the middle of Market Street. The market once described as a common nuisance to Broad Street is long gone, but it deserves an honorable mention in present and future conversations about our shared past.

[1] The area presently known as the City Market was given to the City Council of Charleston by seven property owners in March 1788 for use as a public marketplace. At least one brick and one wooden shed were built on the site by 1789, but the city government converted these market sheds into dormitories in late 1793 to house refugees fleeing the slave revolt in Saint Domingue (Haiti). City Council renegotiated the use of the property with the original grantors in 1805, and the site officially reopened as a market place on 1 August 1807. Details of these events will appear in future episodes of Charleston Time Machine.

[2] A team of archaeologists led by Martha Zierden found artifacts in the basement of Charleston’s City Hall in 2004 confirming the existence of a beef market at that site during second half of the eighteenth century. A city-funded exhibit within the building’s ground floor, which opened to the public in 2007, interprets these findings as physical evidence of Charleston’s first marketplace. That conclusion was repeated in the associated archaeological report: Martha A. Zierden and Elizabeth J. Reitz, Archaeology at City Hall: Charleston’s Colonial Beef Market (Charleston, S.C. Charleston Museum, 2005), 11. For reference to the city’s earliest market, the authors cite Carl Bridenbaugh, Cities in the Wilderness: The First Century of Urban Life in America, 1625–1742 (New York: The Ronald Press, 1938), 193, 351–52. Mr. Bridenbaugh’s conclusions about market activity in colonial Charleston, 1690–1722, are completely erroneous, however, and should be disregarded by modern historians with better access to relevant primary sources.

[3] Activities occurring within Charleston’s early food markets did not include the sales of enslaved people. Readers interested in learning about the sites used for such sales within urban Charleston are invited to peruse Episodes No. 125, No. 126, and No. 187 of Charleston Time Machine.

[4] Guy Miege, The Present State of Great-Britain and Ireland: In Three Parts (London: J. Nicholson, 1715), 295. In this quotation, and others throughout this essay, I have retained the spelling used in the original source.

[5] See, for example, M. J. Power, “London and the Control of the ‘Crisis’ of the 1590s,” History 70 (October 1985): 371–85; Joseph Besse, A Collection of the Sufferings of the People Called Quakers, volume 1 (London, Luke Hinde, 1753), 150; W. Cotton and Henry Woollcombe, Gleanings from the Municipal and Cathedral Records Relative to the History of the City of Exeter (Exeter: James Townsend, 1877), 125, 167; Boston, Massachusetts, A Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston, Containing the Records of Boston Selectmen, 1701 to 1715 (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1884), 62; Richard Hall, ed., Acts, Passed in the Island of Barbados, from 1643, to 1762, Inclusive (London: Richard Hall, 1764), 8–11, 436–42.

[6] The earliest records of real estate grants and conveyances within urban Charleston contain numerous references to Meeting Street (before it acquired that name) as “the street that leadeth from the Ashley River to the market place,” and numerous references to Broad Street as “the street that leadeth from the Cooper River to the market place.” For examples of such nomenclature, see Susan Baldwin Bates and Harriott Cheves Leland, eds. Proprietary Records of South Carolina, Volume Three: Abstracts of the Records of the Surveyor General of the Province, Charles Towne, 1678–1698 (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2007). These early references to the town’s “market place” clearly stem from the 1672 reservation for such a feature in the Grand Model of the town, but they do not necessarily indicate the presence of a market at the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets at the time in question.

[7] See the conveyance of Thomas Bullin (or Bulline) to Edward Rawlins, dated 30 August 1694, which quotes from a now-lost 1686 conveyance, in Susan Baldwin Bates and Harriott Cheves Leland, eds., Proprietary Records of South Carolina, Volume Two: Abstracts of the Records of the Register of the Province, 1675–1696 (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2006), 138.

[8] The title of Act No. 80, “An Act to Prohibit the Engrossing of Salt, and to Ascertain Weights and Measures, and to appoint a Market Place in Charles Town,” ratified on 15 October 1692 and to be in force for twenty four months, appears in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 2 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1837), 73, but the text of the law does not survive in any form.

[9] For more information about these topics, see Charleston Time Machine Episode No 180), “The Genesis of East Bay Street: Charleston’s First Wharf, 1680–1696”; Episode No. 181, “Planning Charleston’s First ‘Fortress,’ 1695–96”; Episode No. 197, “Granville Bastion and the Unfinished Fort of 1697”; Episode No. 77, “The Watch House: South Carolina’s First Police Station, 1701–1725”; and Episode No. 210, “Charleston’s Half-Moon Battery, 1694–1768.”

[10] Grant to Surveyor General Edmund Bellinger, 3 January 1699/1700, Charleston Country Register of Deeds, Book W: 211–13.

[11] A. S. Salley, Jr., ed., Journal of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina For the Session Beginning October 30, 1700 and Ending November 16, 1700 (Columbia: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1924), 21 (15 November 1700).

[12] A. S. Salley, Jr., ed., Journal of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina For the Session Beginning February 4, 1701 and Ending March 1, 1701 (Columbia: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1925), 19 (28 February 1700/1).

[13] Act No. 190, “An Act for Settling a Watch in Charlestown, and for preventing of Fires and Nusances in the same, and for the securing twenty foot on each side the Halfe-moon, for publick landing places,” ratified on 28 August 1701, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 17–22.

[14] South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, 1702–6 (Green’s transcription), page 250 (5 October 1704).

[15] Alexander S. Salley Jr., ed., Journal of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina, March 6, 1705/6--April 9, 1706 (Columbia: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1937), 11 (7 March 1705/6), 20, 30, 39, 40, 41.

[16] The title only of Act No. 294, “An Act to appoint and erect a Market in Charles Town, for the Publick sale of Provisions, and against Regrators, Forestallers and Ingrossers,” ratified on 8 April 1710, appears in Statutes at Large, 2: 351, but the text is found at SCDAH in the manuscript “New Collection” of permanent laws compiled by Nicholas Trott (series S165004), pp. 31–38.

[17] Edward Hakes was appointed “public measurer and guager” for Charleston in Act No. 291, “Act to prevent abuses by false weights and measures, and to appoint a sworn measurer, with a Clause to prevent the Scarcity of Corn,” ratified on 8 April 1710, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 2: 346–47; Section III of the market act of 1710 appointed that same officer to be clerk of the market, but it did not name Hakes specifically. The names of all subsequent market clerks appear in the extant journals of South Carolina’s Commons House of Assembly.

[18] See section VI of the 1710 market act.

[19] See section IV of the 1710 market act.

[20] SCDAH, microfilm of the Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, July–September 1721, now held at the National Archives, Kew, CO 5/426, page 129 (15 September 1721).

[21] See Act No. 445, “An Act for the maintaining a Watch and Keeping Good Orders in Charles Town,” ratified on 15 September 1721. The text of this law does not appear in the published volumes of The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, but the text survives in the engrossed manuscript at SCDAH.

[22] See the deposition of Edward Vanvelsen, 16 September 1729, in a case that commenced on 26 August 1729 concerning a seaman’s wages aboard the merchant vessel William, on National Archives microfilm of Pre-Federal Admiralty Court Records, Province and State of South Carolina, 1716–1732, reel no. 1, volume 2, accessed at CCPL’s South Carolina History Room.

[23] The market act of 1710 was continued for two years on 12 December 1712 by Act No. 331 (see Cooper, Statutes at Large, 2: 604); for another two years on 18 December 1714 by Act No. 342 (see Cooper, Statutes at Large, 2: 618); and revived for several further months on 17 February 1720/1 by Act No. 430 (the text of which was not included in the published Statutes at Large, but is found among the engrossed acts at SCDAH).

[24] See Bruce T. McCully, “The Charleston Government Act of 1722: A Neglected Document,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 83 (October 1982): 303–19.

[25] Alexander S. Salley Jr., ed., Journal of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina for the Session Beginning February 23, 1724/5 and Ending June 1, 1725 (Columbia: Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1945), 55–56 (19 March 1724/5).

[26] Salley, Journal of the Commons House, 1725, 82–83 (9 April 1725).

[27] SCDAH, Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, No. 4 (1727–30), 164 (8 March 1727/8).

[28] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, January 1727/8–February 1728/9 (Sainsbury’s transcription), pages 438–39, 441 (7–8 March 1727/8). President Arthur Middleton and the Council concurred with this resolution; see SCDAH, Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, No. 4 (1727–30), page 164 (7–8 March 1727/8).

[29] SCDAH, Commons House Journal, January 1727/8–February 1728/9 (Sainsbury’s transcription), 486 (10 April 1728). The extant legislative journals contain no further references to this bill during the remainder of this legislative session. The bill apparently died when the assembly was dissolved on 11 May 1728. For an overview of this unproductive period of the General Assembly, see M. Eugene Sirmans, Colonial South Carolina: A Political History 1663–1763 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966), 158–63.

[30] SCDAH, Commons House Journal, 20 January 1730/1–22 September 1733 (Sainsbury’s transcription), p. 979 (15 March 1732/3).

[31] SCDAH, Commons House Journal, 20 January 1730/1–22 September 1733 (Sainsbury’s transcription), p. 995 (5 April 1733).

[32] SCDAH, Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, No. 5, page 574 (26 February 1733/4); SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, 1731–1734 (Sainsbury’s transcription), page 128 (27 February 1733/4).

[33] South Carolina Gazette (hereafter SCG), 24–31 May 1735 (Saturday), No. 70, page 3; SCG, 22–29 November 1735, page 5.

[34] William Linthwaite, brazier, to Margaret Child, widow, mortgage by lease and release, 13–14 January 1735/6 (in the ninth regnal year of George II), Charleston County Register of Deeds, book R: 338–42.

NEXT: The Genesis of North Charleston’s Oldest and Newest Library

PREVIOUSLY: Blanche Petit Barbot: A Musical Life in Charleston

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments