Charleston’s Defensive Strategy of 1703

Processing Request

Processing Request

When Queen Anne of England declared war on France and Spain in 1702, the people of South Carolina were overwhelmed with anxiety about the security of Charleston, the colonial capital. Fortifications built along the town’s eastern waterfront provided some protection against potential invaders, but the rest of the community was open to attack. After a Carolina military expedition failed to capture Spanish St. Augustine, the provincial government adopted an emergency plan in late 1703 to build an entrenchment around Charleston—an earthen wall and moat to surround and protect the capital’s urban core.

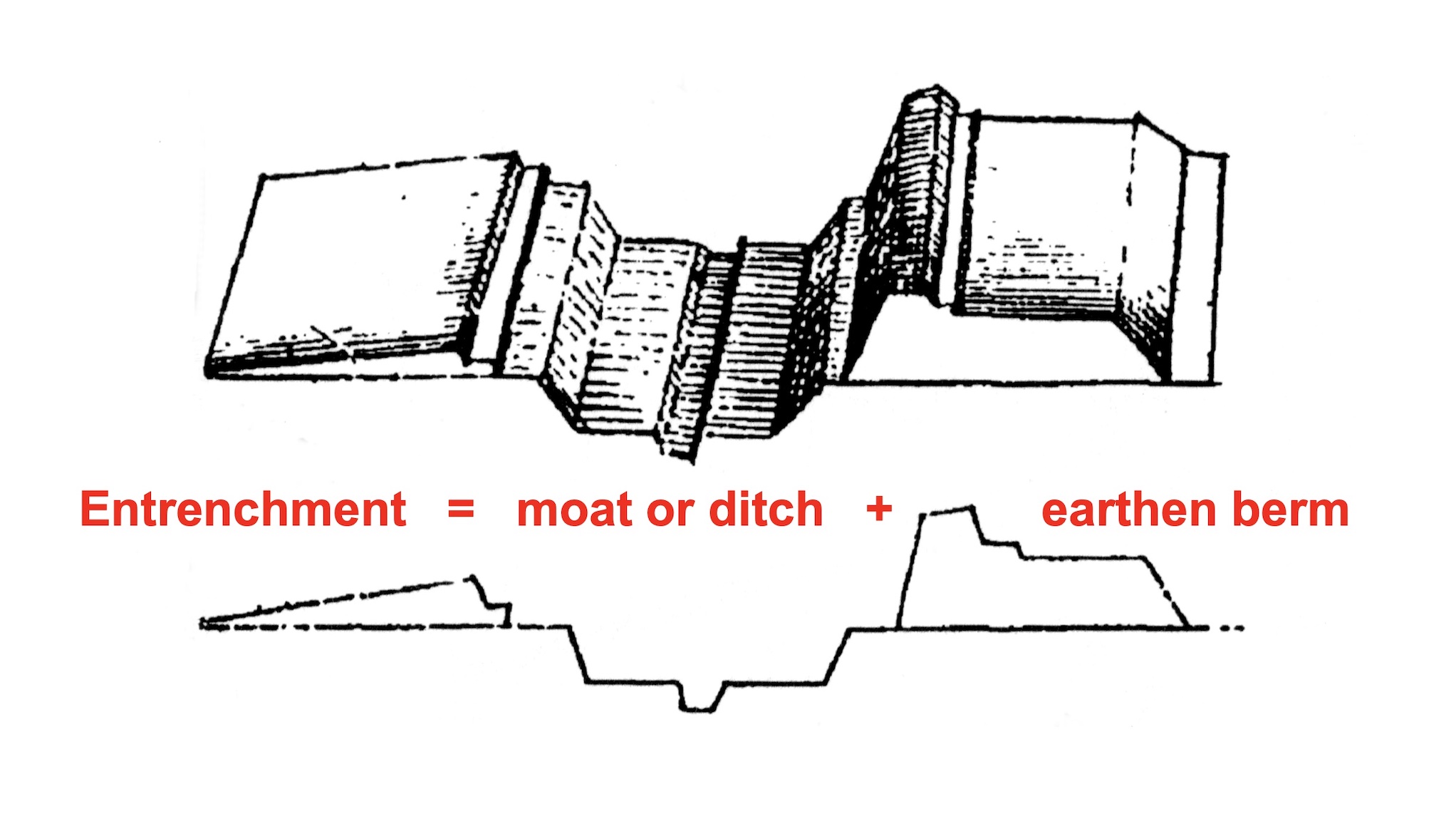

“Entrenchment” is a term used in military architecture to describe a pair of linear defensive components often used to protect a specific area like a town. First, workers excavate a perimeter trench or ditch or moat to slow or deter attackers on foot or on horseback. Second, workers pile the excavated earth next to the ditch to form a defensive berm. The resulting berm or “entrenchment” serves as a protective barrier to shield defenders and repulse attackers who might approach or traverse the ditch. Due to the nature of the materials involved, entrenchments are relatively inexpensive and simple to create, but they are inherently impermanent works. They are best suited for temporary occasions, like sieges, in which an attacker arrives at the perimeter of a town or castle and rapidly constructs a line of entrenchment to defend its approach. To render such earthworks more permanent, builders can add rigid materials like bundles of sticks (fascines), boards, bricks, or stones to hold the earth in place. These materials provide reinforcement, or “revetment,” that can extend the lifespan of an entrenchment indefinitely if properly maintained.

The earthen entrenchments constructed within urban Charleston during the early years of eighteenth century endured on the landscape for a single generation, but they have long formed one of the most iconic and misunderstood features in the narrative of local history. The so-called “Crisp Map” of South Carolina, published in London in 1711, depicts Charleston as what we might describe as a “walled city,” outlined by a trapezoid-shaped network of walls, moats, bastions, redans, and drawbridges. This illustration has been reproduced in countless books and articles over the past three centuries, accompanied by vague descriptions of the town’s early defenses. Absent among this literature, however, is any detailed discussion of when, why, and how Charleston’s earthen walls were created. Today’s program focuses solely on the historical context that triggered the decision to enclose the town behind a defensive wall and moat. In future programs, we’ll continue this narrative by examining the methods of constructing the entrenchments, the ongoing efforts to repair them, and the eventual decision to remove them from the urban landscape.

Shortly after moving the capital of South Carolina to the peninsula known as Oyster Point in 1680, the provincial legislature authorized the construction of some rudimentary fortifications made of earth and wood along the Cooper River waterfront of “new” Charles Towne (now Charleston). Work commenced in 1694 to build a brick “wharf wall” along the east side of modern East Bay Street, measuring nearly one half of a mile in length. The storm surge associated with a strong hurricane in the autumn of 1700 ruined much of the initial brickwork, but the project quickly rebounded and continued. By the summer of 1702, South Carolina’s provincial government mounted two dozen cannon at three emplacements along the unfinished brick “wharf wall”: an unfinished brick “fort” (later called Granville Bastion) at the southern end of the Bay, a small battery of unknown materials at the east end of Tradd Street; and a completed brick Half Moon Battery at the east end of Broad Street. Beyond these works along Charleston’s eastern waterfront, the south, west, and northern parts of the town remained unguarded.

Shortly after moving the capital of South Carolina to the peninsula known as Oyster Point in 1680, the provincial legislature authorized the construction of some rudimentary fortifications made of earth and wood along the Cooper River waterfront of “new” Charles Towne (now Charleston). Work commenced in 1694 to build a brick “wharf wall” along the east side of modern East Bay Street, measuring nearly one half of a mile in length. The storm surge associated with a strong hurricane in the autumn of 1700 ruined much of the initial brickwork, but the project quickly rebounded and continued. By the summer of 1702, South Carolina’s provincial government mounted two dozen cannon at three emplacements along the unfinished brick “wharf wall”: an unfinished brick “fort” (later called Granville Bastion) at the southern end of the Bay, a small battery of unknown materials at the east end of Tradd Street; and a completed brick Half Moon Battery at the east end of Broad Street. Beyond these works along Charleston’s eastern waterfront, the south, west, and northern parts of the town remained unguarded.

In August 1702, news arrived in Charleston that King William II of England had died in March, and his successor, Queen Anne, had declared war on France and Spain in May. Historians refer to this international conflict as Queen Anne’s War, or the War of Spanish Succession, which was destined to last for eleven years. Although most of the fighting took place in Europe, the conflict extended across the Atlantic to include the various colonies in the Americas. For the first time since the settlement of the South Carolina in 1670, a state of formal warfare now existed between the English government in Charleston and the Spanish government at St. Augustine, Florida. The Floridians had recently completed an impressive stone fortress, the Castillo de San Marcos, to defend their capital, while the waterfront defenses of Charleston remained relatively weak and unfinished. After learning of the new declaration of war, South Carolina’s provincial government was compelled to consider methods of improving the fortifications around its capital as quickly and cheaply as possible.

During a legislative session held in August and September 1702, the South Carolina General Assembly ordered the continuation of work on the existing waterfront fortifications, but did not discuss plans for any new defensive works around the capital town. Instead, the provincial government chose to pursue an offensive strategy. Governor James Moore convinced the assembly to fund a preemptive attack on the capital of Spanish Florida rather than wait for Spanish forces based in St. Augustine or Havana to launch an attack on the capital of South Carolina.[1] After weeks of planning and preparation, a squadron of vessels and armed men sailed from Charleston in October 1702 and commenced a siege of St. Augustine in early November. The Carolina forces sacked and burned the town, but lacked sufficient firepower to subdue Spanish forces ensconced within the Castillo de San Marcos. Governor Moore later acknowledged that the “castle” of San Marcos was “much stronger then [sic] it hath been represented to us by any person.”[2] When shiploads of Spanish reinforcements arrived from Havana in late December, the South Carolina troops set fire to their own vessels and marched home over land.[3]

During a legislative session held in August and September 1702, the South Carolina General Assembly ordered the continuation of work on the existing waterfront fortifications, but did not discuss plans for any new defensive works around the capital town. Instead, the provincial government chose to pursue an offensive strategy. Governor James Moore convinced the assembly to fund a preemptive attack on the capital of Spanish Florida rather than wait for Spanish forces based in St. Augustine or Havana to launch an attack on the capital of South Carolina.[1] After weeks of planning and preparation, a squadron of vessels and armed men sailed from Charleston in October 1702 and commenced a siege of St. Augustine in early November. The Carolina forces sacked and burned the town, but lacked sufficient firepower to subdue Spanish forces ensconced within the Castillo de San Marcos. Governor Moore later acknowledged that the “castle” of San Marcos was “much stronger then [sic] it hath been represented to us by any person.”[2] When shiploads of Spanish reinforcements arrived from Havana in late December, the South Carolina troops set fire to their own vessels and marched home over land.[3]

Two weeks after abandoning the siege of St. Augustine, Governor Moore was back in Charleston to address the opening of a new session of the South Carolina General Assembly. The text of his speech to the Commons House on January 14th, 1703, does not survive, but the response from the House provides an outline of its content. Having failed in his recent effort to conquer the capital of La Florida, Governor Moore warned his colleagues that Spanish forces would likely retaliate by launching an attack on the capital of South Carolina. He therefore advised the assembly to consider various ways and means of improving the defensive works around urban Charleston. The Commons House immediately appointed a committee to consider this topic, and one week later, on 23 January, the committee presented to the House a report and “a platt to make Charles Towne more defencible.”[4]

Political squabbling over the failed raid on St. Augustine postponed debate of the committee’s report and plat until February 18th. After a brief, unrecorded discussion on that date, the members of the Commons House resolved “that there be an entrenchment on ye back part of ye towne, for the security thereof.” This rather vague phrase suggests a plan to trace a line of entrenchment around the undefended parts of Charleston, to the south, north, and west of the small settlement crowded along the Cooper River waterfront. Although details are lacking to confirm the nature of the plan submitted in February 1703, the report and plat were sufficiently robust for the Commons House to order one of its members to prepare a bill to implement and fund the proposed entrenchments. That bill never materialized, however, because the assembly adjourned for a recess one week later and was then dissolved when Sir Nathaniel Johnson received a commission to serve as governor of South Carolina.[5]

After a round of provincial elections in late March, a new General Assembly convened in Charleston in mid-April 1703. Governor Johnson, like his predecessor, encouraged the Commons House to finish the waterfront fortifications and consider methods of making the rest of Charleston more defensible. A committee assigned to this task submitted on May 7th a plan to “make a work or trenchm[en]t,” but the geographic scope of this new plan was more specific than the one mentioned several months earlier. It was to be confined to the southern tip of the peninsula, “att ye White point for ye defence & safty of soldiers when comanded to oppose ye landing of an enemy in that place.” Furthermore, the Commons House assigned a sort of hypothetical status to the proposed entrenchment by ordering it to be made “in such place, & in such forme & at such time, as ye Generall [Governor Johnson] shall direct & order.” Johnson made no such orders, however, and in September the legislature voted to suspend further consideration of the proposed “breast worke along ye White point.”[6]

The decision to postpone discussion of new fortifications in Charleston was soon reversed by the arrival of terrifying news. In the autumn of 1703, a combined Spanish and French force sailed from Havana and sacked the town of Nassau, the capital of the English colony of the Bahama Islands.[7] The invaders obliterated the settlement, murdered scores of inhabitants, and held the English governor as a prisoner for ransom. Former South Carolina governor Robert Quary was residing in Virginia when he heard news of the raid that October, and immediately feared for the safety of his former neighbors. Quary informed the English government that “the next step will be ye taking of Carolina,” and lamented that the people of Charleston were “in no condition to defend themselves.”[8]

The decision to postpone discussion of new fortifications in Charleston was soon reversed by the arrival of terrifying news. In the autumn of 1703, a combined Spanish and French force sailed from Havana and sacked the town of Nassau, the capital of the English colony of the Bahama Islands.[7] The invaders obliterated the settlement, murdered scores of inhabitants, and held the English governor as a prisoner for ransom. Former South Carolina governor Robert Quary was residing in Virginia when he heard news of the raid that October, and immediately feared for the safety of his former neighbors. Quary informed the English government that “the next step will be ye taking of Carolina,” and lamented that the people of Charleston were “in no condition to defend themselves.”[8]

Governor Nathaniel Johnson shared Quary’s fear. In November 1703, after hearing credible intelligence that Spanish forces were preparing to attack South Carolina, Johnson called for an emergency legislative session to address the potential danger.[9] The elected representatives gathered in Charleston on December 7th, and the following day heard a rousing speech from the governor. The text of Johnson’s speech does not survive, but, as with Governor Moore’s speech a year earlier, the formal response from the Commons House provides an outline of its content. On December 9th, the Commons House sent Johnson a message of thanks: “Wee the Commons returne your Honr. the hearty thanks of the House for your kind speech, and for your great care over us, in calling us to meet together in this dangerous juncture, to consult upon methods for the security of this province.”

After commending the governor for his vigorous leadership “in the time of allarum,” the Commons House began to debate various topics suggested in Johnson’s speech. The first “article” of their discussion responded to the crux of the governor’s advice: “The Question is, whether this House is of opinion that an entrenchment shall be drawn through part of Charlestowne for the defence of the same.” After the votes were tallied, the question “carried in the affirmative,” and the House appointed a committee “to view the most proper ground for the s[ai]d entrenchment to be made, and draw a platt of the same, and present it to this House tomorrow.”[10]

The members of the committee assigned this task commenced their work immediately, but apparently were unsure how to proceed. Unless they had prior experience with building fortifications, they might have pondered a number of practical topics, such as how broad and how deep to dig the moat, how broad to make the earthen rampart, how tall to pile the parapet wall, and how to prevent the earthen walls from washing away during rainstorms. If the line of the proposed entrenchment was to be “drawn through part of Charlestowne,” which part of the town should be included within the walls, and which parts excluded? Once they had perfected a scaled plan on paper, how were they supposed to transfer the design onto the urban landscape?

To resolve such hypothetical questions, the Commons House sent two of its members to visit the governor on December 10th, “to know his opinion upon the entrenchments.” Sir Nathaniel Johnson was a man of significant military experience in the English army, but he apparently lacked practical knowledge related to the design and construction of fortifications. To assist with such matters, the governor advised the Commons House “that Capt. Sam. Du Burdaux and Mr. Lomboyce be sent for to have their opinions upon the entrenchment of the Towne.” To expedite invitations to these men, Governor Johnson volunteered to “send for Lomboyce,” while the Commons House agreed to summon Du Burdaux.[11]

The two men in question were both Huguenot immigrants, French Protestants who had come to South Carolina in the late seventeenth century to escape religious persecution in their homeland. Their names are rendered in a variety of misspellings among the extant records of South Carolina’s early government, but we can identify the subjects with some confidence. Samuel DuBourdieu, “squire,” migrated from Brittany in Northern France to Charleston in 1686. He soon moved northward with a handful of other Huguenots to settle on the frontier area along the Santee River. Although he later moved westward to a plantation near the western branch of the Cooper River, part of the DuBordieu family moved northward into modern Georgetown County where the name is now pronounced “Debidue.”[12] Similarly, Jacques le Grand, sieur de Lomboy (1659–1725) was a native of Normandy in northern France who came to South Carolina before the end of the seventeenth century. Like Mons. DuBourdieu, Jacques or James de Lomboy settled among other Huguenot refugees along the Santee River and lived the rest of his life primarily as a rural planter.[13]

The two men in question were both Huguenot immigrants, French Protestants who had come to South Carolina in the late seventeenth century to escape religious persecution in their homeland. Their names are rendered in a variety of misspellings among the extant records of South Carolina’s early government, but we can identify the subjects with some confidence. Samuel DuBourdieu, “squire,” migrated from Brittany in Northern France to Charleston in 1686. He soon moved northward with a handful of other Huguenots to settle on the frontier area along the Santee River. Although he later moved westward to a plantation near the western branch of the Cooper River, part of the DuBordieu family moved northward into modern Georgetown County where the name is now pronounced “Debidue.”[12] Similarly, Jacques le Grand, sieur de Lomboy (1659–1725) was a native of Normandy in northern France who came to South Carolina before the end of the seventeenth century. Like Mons. DuBourdieu, Jacques or James de Lomboy settled among other Huguenot refugees along the Santee River and lived the rest of his life primarily as a rural planter.[13]

In mid-December 1703, South Carolina’s predominantly-English government reached out to a pair of French immigrants for military advice during an emergency situation. This gesture suggests that Messieurs DuBourdieu and Lomboy possessed some particular knowledge of military architecture, engineering, or project management, or some combination thereof. Details related to their professional experiences in France are now lacking, but we know that the members of the South Carolina government valued the knowledge and skills of their French neighbors in 1703, and invited them to contribute to the defense of their new home.

On December 17th, one week after the government reached out to the Huguenots living on the rural frontier, Samuel DuBordieu visited the Commons House of Assembly and “laid before this House a draught of the fortifications of Charlestowne.” The House immediately appointed a committee to inspect the submitted draught, “to supervise the lines of the s[ai]d fortifications, and report the damages that the said lines [of the entrenchment] may do to each inhabitants lott, tomorrow.”[14] The committee reported the next day that “the said line is little or no damage to the owners of those lotts it runeth over.” The committee added “that they also approve of the draught of the said fortification, already drawn, and brought into this House by Capt. Du Burdeaux.”[15]

The lines of entrenchment drawn around Charleston by Samuel DuBourdieu in 1703 cut through both public streets and private lots. This intrusion did not cause great hardship to the town’s inhabitants, however, because the vast majority of the residences and businesses were clustered near modern East Bay Street, between the south side of modern Tradd Street and the south side of modern Queen Street. Beyond the Anglican Church at the southeast corner of Meeting and Broad Streets, and the Congregational Meeting House a few hundred yards to the north, there was very little development standing on the west side of modern Meeting Street in the winter of 1703. DuBourdieu’s “draught” struck a balance between two competing interests. The outline or “trace” he submitted to the provincial government was sufficiently large to avoid passing through numerous settled properties, but sufficiently small to create an “enceinte” or enclosure that could be defended by the town’s small population of adult White males. The government was prepared to compensate property owners impacted by the exercise of eminent domain, and the community was willing to tolerate the temporary closure of a few streets in order to survive the present emergency. The immediate threat was real, and, as later government records indicate, the local population understood that the intrusive earthen fortifications would not stand forever.

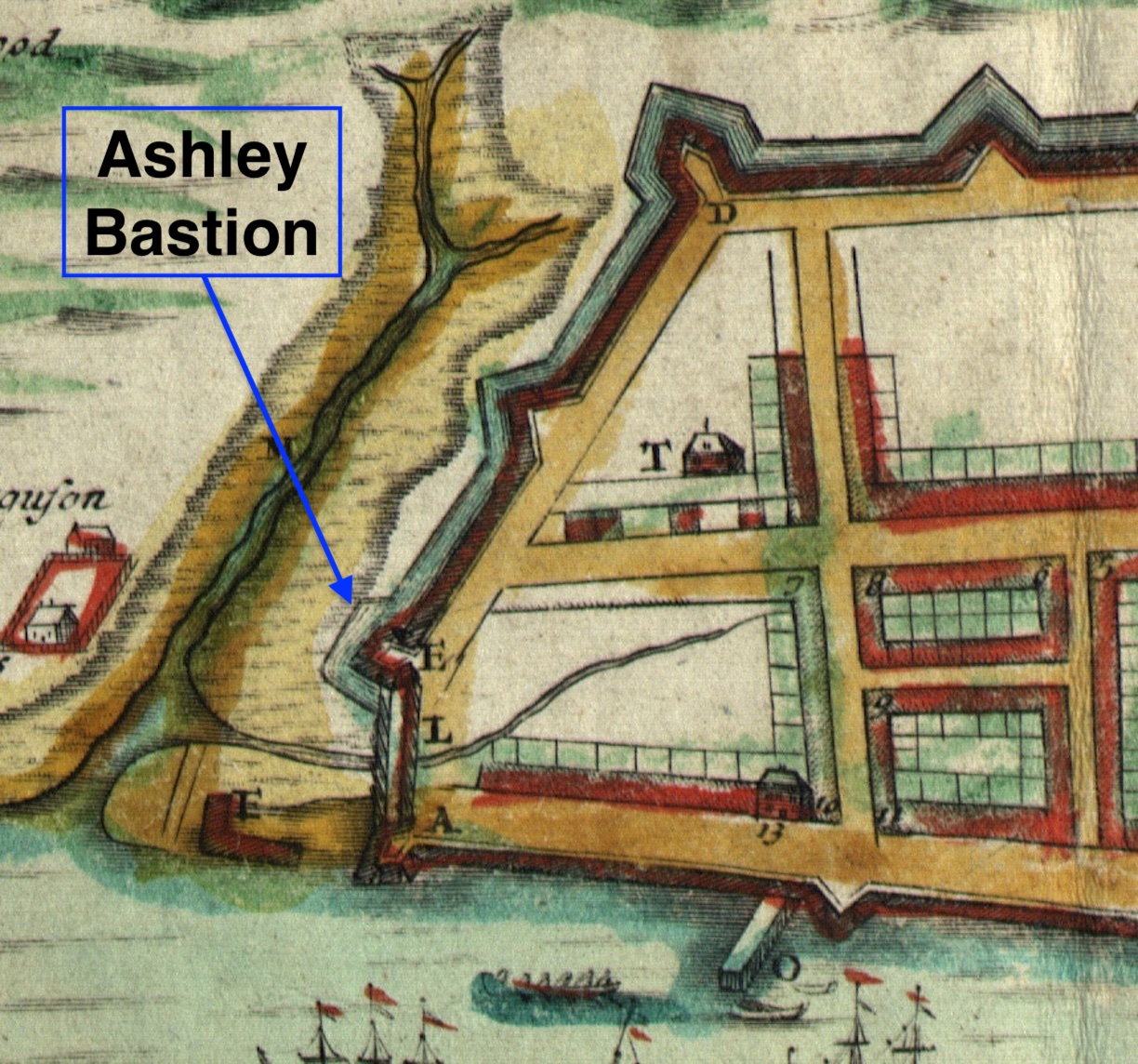

Once the committee began laying out the lines of entrenchment on the landscape, they encountered a conundrum beyond their collective experience. After voicing some unspecified questions to the Commons House on December 21st, the Speaker of the House ordered the committee “to view again the line of fortification and discourse Mr. Longboice [Lomboy] for further advice, and report the same to this House tomorrow morning.”[16] Their questions apparently related to the geometry of military architecture. Fortification theory of that era required a clear line of sight between a bastion or gun emplacement and its neighboring bastions to the left and right, to facilitate lines of fire for their mutual defense during an attack. For reasons unknown, the proposed line of entrenchment along the south side of the town did not or could not follow a straight path from the town’s principal gun battery (later known as Granville Bastion) on the east to the new bastion proposed to stand at the southwest corner of Meeting and Tradd Streets (now the site of the First Scots Church). The line in question, as drafted by Monsieur DuBourdieu and perhaps altered to suit property owners at the southern end of modern Church Street, included a jog or bend in the line that would obstruct the line of fire between the southeastern and southwestern bastions.[17] After viewing the ground with Monsieur Lomboy, the committee reported the next day “that it is necessary for clearing the line of entrenchment from the Great Battery [Granville Bastion] to add a small bastion 21 foot long and 14 foot wide.” Although this brief description does not specify the location of the proposed additional battery, and the dimensions were probably muddled by a nineteenth-century copyist, the structure resulting from this discussion is almost certainly the feature identified on the “Crisp Map” of 1711 as “Ashley Bastion.”[18]

Once the committee began laying out the lines of entrenchment on the landscape, they encountered a conundrum beyond their collective experience. After voicing some unspecified questions to the Commons House on December 21st, the Speaker of the House ordered the committee “to view again the line of fortification and discourse Mr. Longboice [Lomboy] for further advice, and report the same to this House tomorrow morning.”[16] Their questions apparently related to the geometry of military architecture. Fortification theory of that era required a clear line of sight between a bastion or gun emplacement and its neighboring bastions to the left and right, to facilitate lines of fire for their mutual defense during an attack. For reasons unknown, the proposed line of entrenchment along the south side of the town did not or could not follow a straight path from the town’s principal gun battery (later known as Granville Bastion) on the east to the new bastion proposed to stand at the southwest corner of Meeting and Tradd Streets (now the site of the First Scots Church). The line in question, as drafted by Monsieur DuBourdieu and perhaps altered to suit property owners at the southern end of modern Church Street, included a jog or bend in the line that would obstruct the line of fire between the southeastern and southwestern bastions.[17] After viewing the ground with Monsieur Lomboy, the committee reported the next day “that it is necessary for clearing the line of entrenchment from the Great Battery [Granville Bastion] to add a small bastion 21 foot long and 14 foot wide.” Although this brief description does not specify the location of the proposed additional battery, and the dimensions were probably muddled by a nineteenth-century copyist, the structure resulting from this discussion is almost certainly the feature identified on the “Crisp Map” of 1711 as “Ashley Bastion.”[18]

On the 23rd of December, 1703, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified a new law titled “An Additional Act to an Act entituled ‘An Act to prevent the Sea’s further encroachment upon the Wharfe at Charles Town’; and for the repairing and building more Batterys and Flankers on the said Wall to be built on the said Wharfe; and also for the fortifying the remaining parts of Charles Town by Intrenchments, Flankers and Pallisadoes, and appointing a Garrison to the Southward.” The initial paragraphs of this “entrenchment act of 1703,” as we might call it, included instructions for finishing the brick wharf wall along the east side of East Bay Street. That material forms a continuation of legislation ratified in the autumn of 1700 and lies outside the scope of the present conversation, however, so I’ll defer discussion of it to a future program about of the waterfront brickwork.[19]

The bulk of the lengthy text of the 1703 act relates to the application of public funds to the construction of “such additional walls, gates and other conveniences for the men [that] shall be added to the great battery [Granville’s Bastion] and the halfe moone at the watch-house[,] as shall be ordered by an ordinance of the General Assembly.” As we have seen, however, the assembly had already partnered with Samuel DuBourdieu and James de Lomboy to design and plan the execution of a line of entrenchments around the town. The act of December 23rd merely set that plan in motion.[20]

To execute the defensive works designed in great haste in December 1703, the provincial government appointed Lieutenant Colonel William Rhett (1666–1723) to act as the “sole commissioner” of the project. Although some historians have misinterpreted Rhett’s contributions to Charleston’s early fortifications, his role was clearly administrative. Like the general contractor of a modern construction project, Rhett was in charge of procuring the materials, tools, and labor required to execute the plans created by other specialists. The law empowered Rhett to “impress” or commandeer enslaved laborers, tools, equipment, and materials needed for the fortifications, and to issue IOUs that the General Assembly would pay at some future date.[21] To clarify the objective of this public-works project, the text of the act defined the general outline of the entrenchments to enclose the “back” of the town:

“That is to say, from the angle of the great fort [Granville Bastion] to the end of the Church-street [the modern intersection of Meeting Street at Tradd Street], and from the angle of the said street to the swamp near Mr. Archibald Stobo’s meeting house [the modern intersection of modern Meeting and Cumberland Streets], and from the said meeting house eastward to the said battery, that is appointed to be built at the northernmost angle of Col. Robert Daniel’s northernmost lot, fronting Cooper River [that is, at the southeast corner of modern East Bay and Market Streets]; which said fortifications shall be [made] by intrenchments, flankers and parapets, sally ports, a gate, drawbridge and blind necessary for the same, and shall be made at the sole charge and expence of the publick, and according to such method as the said William Rhett, who is also hereby appointed the sole commissioner for manageing these additional fortifications, shall, with the advice and consent of the Right Honorable the Governor as aforesaid, direct.”[22]

Rhett was authorized to cut down any trees standing in the path of the entrenchment or judged “prejudicial” to the fortifications, and to take from nearby forests whatever pine trees might be required for the works. The text of the 1703 act does not articulate the purpose of such pine trees, but they were likely intended to create revetments to hold the earthen walls in place. Similarly, the act promised future compensation to the owners of “any lott or part of a lott” in Charleston by appraising “so much ground as shall be used in the fortifications.” The extant public records of this era contain no references to the removal of any houses standing in the path of the entrenchments, but the excavations undoubtedly required the removal of numerous fences enclosing private lots, pastures, and gardens on the periphery of the young settlement.[23]

Immediately after ratifying the act to initiate the entrenchments, the South Carolina Commons House ordered the public treasurer to pay £10 sterling to Captain Samuel DuBourdieu “for his trouble and charges in drawing the line, for the entrenchment, designed for Charlestowne, and drawing a platt of the same.”[24] James de Lomboy later received a much larger reward for his contributions to the town’s defenses, but the bulk of his efforts belong to the next chapter in this story. Between late December 1703 and the end of 1704, scores of enslaved Africans wielded picks and shovels to excavate a continuous broad ditch or moat, measuring nearly a mile in length, around the highest and driest sixty-two acres of urban Charleston. Their labors, under the supervision of James de Lomboy and William Rhett, sculpted a massive wall of earth and wood that protected the capital of South Carolina during an era of great danger.

[1] A. S. Salley, ed., Journals of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina for 1702 (Columbia: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1932), 64–66.

[2] James Moore and Robert Daniel to the Council of South Carolina, November 1702, item No. 1193 in Cecil Headlam, ed., Calendar of State Papers Colonial Series, America and West Indies, volume 20, 1702 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1912), 745–46.

[3] See Charles W. Arnade, The Siege of St. Augustine in 1702 (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1959).

[4] A. S. Salley, ed., Journals of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina for 1703 (Columbia: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1934), 5–7, 10, 12, 16, 22. The committee included Dr. Charles Burnham, James Serrurier Smith, George Logan, and William Smith.

[5] Salley, ed., Journals of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina for 1703, 49.

[6] Salley, ed., Journals of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina for 1703, 95, 90, 118.

[7] John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, volume 2 (London: John Nicholson, 1708), 359–60, says two raids took place in July and October. More reliable sources point to a single raid in late August. See Michael Craton, A History of the Bahamas (London: Collins, 1958), 93.

[8] Robert Quary to the Board of Trade and Plantations, 15 October 1703, item No. 1150 in Cecil Headlam, ed., Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies, volume 21, 1702–1703 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1913), 737.

[9] Alexander Salley’s published transcription of the Journals of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina for 1703 does not include the emergency session of 7–23 December. The original manuscript journal of this session is not extant, but the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH) holds a manuscript copy of it made ca. 1850 by John Sitgreaves Green.

[10] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly (Green’s transcription), 1702–6, pages 197–98. The committee included Captain Parris, Major Colleton, Colonel Logan, and Captain Cantey.

[11] Commons House Journal, 1702–6, page 200. The two representatives were Ralph Izard and James Serrurrier Smith.

[12] Bertrand Van Ruymbeke, From New Babylon to Eden: The Huguenots and their Migration to Colonial South Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2006), 62, 73, 83, 86, 116; Susan Baldwin Bates and Harriott Cheves Leland, French Santee: A Huguenot Settlement in Colonial South Carolina (Baltimore, Md.: Otter Bay Books, 2015), 281, 309–10.

[13] Robert Wilson, ed., “Wills of South Carolina Huguenots,” Transactions of the Huguenot Society of South Carolina 13 (1906): 21–25; Bates and Leland, French Santee, 218–22.

[14] Commons House Journal, 1702–6, page 212. The committee included James Risbee, Richard Beresford, John Stroud, James Serrurier Smith.

[15] Commons House Journal, 1702–6, pages 213–14.

[16] Commons House Journal, 1702–6, page 218.

[17] The conundrum concerning the southern line on 21–22 December 1703 might have been related to the presence of a brick wall extending from Granville Bastion approximately one hundred feet to the west. This wall, which appears on seveal plats as late as 1755, was probably not created during the entrenchment campaign of 1703–4. I believe it represented a vestige of the unfinished fort of 1697 (see Episode No. 197).

[18] Commons House Journal, 1702–6, page 220. The original manuscript journal does not survive, and this description of the additional bastion exists only in Green’s ca. 1850 transcription, which I have triple-checked for accuracy. I believe Mr. Green likely mis-transcribed the numerals in the dimensions of the additional bastion.

[19] See sections I–IV and VIII of Act No. 219, “An Additional Act to an Act entituled ‘An Act to prevent the Sea’s further encroachment upon the Wharfe at Charles Town’; and for the repairing and building more Batterys and Flankers on the said Wall to be built on the said Wharfe; and also for the fortifying the remaining parts of Charles Town by Intrenchments, Flankers and Pallisadoes, and appointing a Garrison to the Southward.,” ratified on 23 December 1703, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 28–33. The engrossed manuscript copy of this act is held at SCDAH.

[20] See section IX of Act No. 219.

[21] See sections V, VI, VII, XI, XV, and XVI of Act No. 219.

[22] See section X of Act No. 219.

[23] See sections XI, XII, XIII of Act No. 219.

[24] Commons House Journal, 1702–6, page 226.

NEXT: A 'Banjer' on the Bay of Charleston in 1766

PREVIOUSLY: The First People of the South Carolina Lowcountry

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments