Blanche Petit Barbot: A Musical Life in Charleston

Processing Request

Processing Request

Blanche Petit was a child prodigy on the piano whose European career commenced at the age of nine in 1851. After she performed in New York the following year, her family settled in Charleston, where her influential father died suddenly in 1856. Thirteen-year-old Blanche then launched an illustrious career as a professional musician, teacher, and conductor in the Palmetto City that continued until her death in 1919. Her dramatic story of triumph and tragedy illuminates the life of a remarkable woman worthy of eternal fame in her adopted home.

Born in Brussels, Belgium, in late December of 1842, Blanche Hermine Petit inherited significant talents from her accomplished parents.[1] An early Charleston reference stated that her mother, Marie Thérèse Provost Petit, had been the “principal of one of the first French academies” in Brussels.[2] Blanche’s father, Victor Petit, was a professional musician and composer who played the piano and violin but excelled as a performer on the clarinet. When his daughter was four years of age, Monsieur Petit introduced Blanche to the piano and encouraged her rapid mastery of the instrument. Besides rigorous instruction at the keyboard, Monsieur Petit provided his daughter with a thorough training in solfège—that is, the art of vocalizing the notes and melodies of a written piece of music, using the syllables do, re, me, fa, sol, la, and ti. This skill, now frequently called “sight-singing” in English, helps musicians gain an intellectual grasp of a new piece of music at first sight. A musician well-versed in solfège can, in theory, render a satisfactory performance of a new piece of music with little or no preparation—a valuable skill for professionals who are frequently required to master new compositions on short notice.

In late August 1849, Victor Petit presented seven-year-old Blanche Hermine at a musical salon in Brussels. Her performance of several complex works elicited praise from one of the leading Belgian pianists of that era, Madame Marie Félicité Pleyel, who predicted that the precocious child would enjoy a brilliant future as a concert artist. Less than two years later, in February 1851, Blanche made her concert debut at the Théàtre Italien-Français in Brussels, which was followed by a year-long series of performances at venues in Belgium, Germany, and Holland. Her performance at the royal court of King William III of Holland in January 1852 might have been a highlight of the tour, but audiences and critics lavished praise on the nine-year-old Blanche wherever she performed.[3]

With her parents and brother, Alfred, Blanche set sail from Belgium in the spring of 1852 and crossed the Atlantic to New York. That May she performed at the fashionable Niblo’s Garden on Broadway and in June at Metropolitan Hall with another precocious nine-year-old, future international opera star Adelina Patti. Executing complex and sophisticated works in the latest musical styles, the young Belgian pianist received glowing reviews with each appearance.[4] “Mlle. Petit is not a child prodigy,” said a New York publication that spring, “she is an artist in miniature, but a true artist.”[5]

The Petit family traveled southward in the autumn of 1852, but the forces that drew them to South Carolina are now obscure. It’s possible that the Belgian family had some contact with a French-speaking relative in Charleston, or they learned in New York of the strong musical appetite displayed by audiences in the Palmetto City. South Carolina’s former capital had once been among the most musical cities in North America, but local musical culture declined significantly after the rise of secessionist politics in the late 1820s. Like many other cities in mid-nineteenth-century America, Charleston became a satellite of an expanding music industry based in New York. Retail outlets in King and Meeting Streets, for example, sold large volumes of musical instruments and printed music imported through New York, while venues like the Charleston Theatre (1837), Hibernian Hall (1840), and Institute Hall (1855) hosted a cavalcade of touring artists who embarked from New York and followed a well-established circuit across multiple states.

Before the Petit family reached Charleston, the local press primed expectations by announcing the imminent arrival of Victor Petit, “one of the first clarionetists [sic] in Europe,” and his daughter, “Hermina Petit, not yet ten years of age.” Quoting from European papers, the Charleston Courier compared the young girl’s musical talent with that of two of the greatest pianists active in Europe—Henri Herz and Sigismond Thalberg—and encouraged Carolinians to welcome the Petit father and daughter with “the patronage they certainly merit—which has been accorded [to] them in Europe, by all classes, including even sovereigns.”[6]

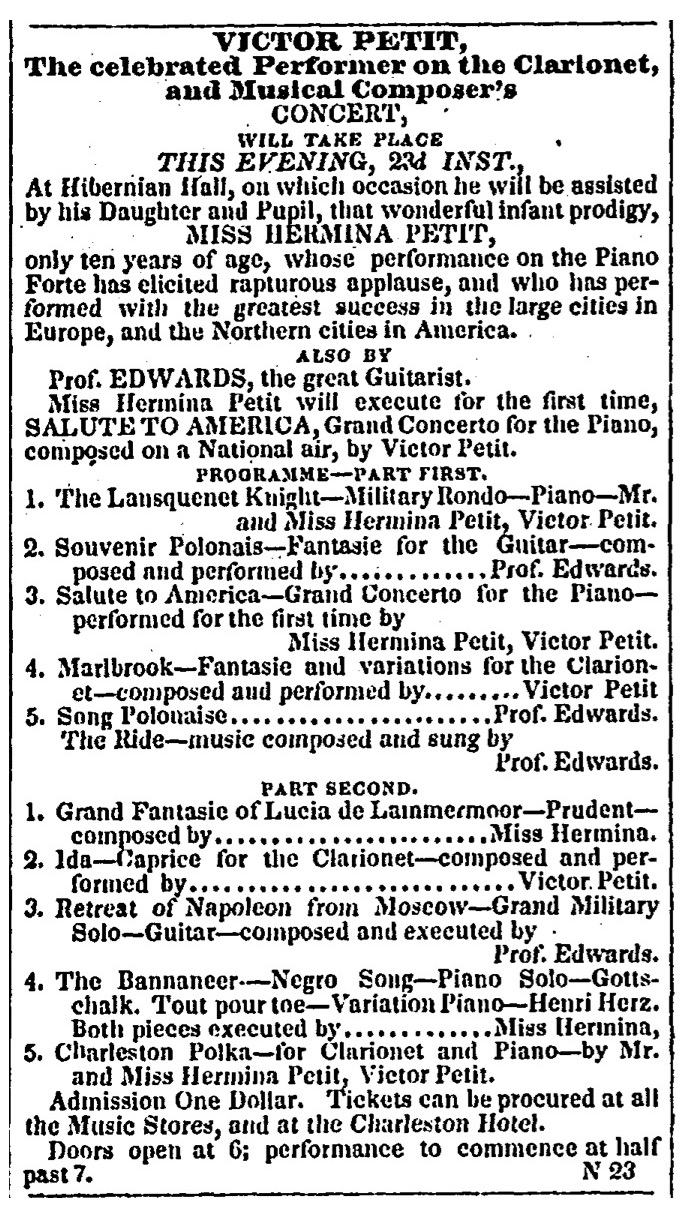

Victor Petit and his family arrived in Charleston on the 19th or 20th of November, 1852, with the stated intention of performing just one or perhaps two public concerts in the city, as prior engagements elsewhere obliged them to keep moving.[7] Their first event took place at Hibernian Hall on November 23rd and included several pieces jointly composed by Monsieur Petit and his daughter, identified as “Hermina” in her earliest Charleston notices. Details of their reception in the Palmetto City are lacking, but the response was apparently sufficient to induce Victor to arrange a second concert at the same venue. Following that performance on November 29th, a mysterious silence obscures an important crossroads in the family’s story.

Having toured northwestern Europe and crossed the Atlantic to showcase their musical talents, the Petit family did not leave Charleston during the winter of 1852–53. On January 4th, Victor announced via the local press his intention, “by request,” to “give courses of instruction on the piano or violin for juvenile beginners—from 4 to 6 in a class,” at the quarterly rate of $18, or individual lessons at the rate of $36 per quarter.[8] This proposal indicated an intention to remain in the city for some indefinite period of time, but the motivations behind his change of plans are unclear. It’s possible that Victor found Charleston irresistibly charming, but it’s also possible that a member of the Petit family became ill and was unable to continue their North American tour. Other musically inclined citizens were, at that very moment, organizing a short-lived entity called the Philharmonic Society of Charleston, and that activity might have convinced Victor to put down roots.[9] Musical life in Baltimore, Philadelphia, Boston, and New York still eclipsed that within the Palmetto City in 1853, however, so the Petit family’s decision to remain in Charleston defies easy explanation. Perhaps Victor and his wife, Marie, were simply looking for a Goldilocks American town, not too big and not too small, in which to raise their children, and Charleston met their requirements.

Marie Petit, mother of the juvenile pianist, announced in April 1853 her intention to form “French classes, for young ladies” in Charleston, designed to enable them “to converse freely in the said language in six months.”[10] Six months later, Victor Petit advertised the formation of solfège classes at the family’s rented residence in Pinckney Street, where Madame Petit also offered evening classes in French for young ladies.[11] Father and daughter presented several more public concerts in Charleston during the ensuing months, and it became clear that the Petit family was becoming a fixture of the city’s cultural life.[12]

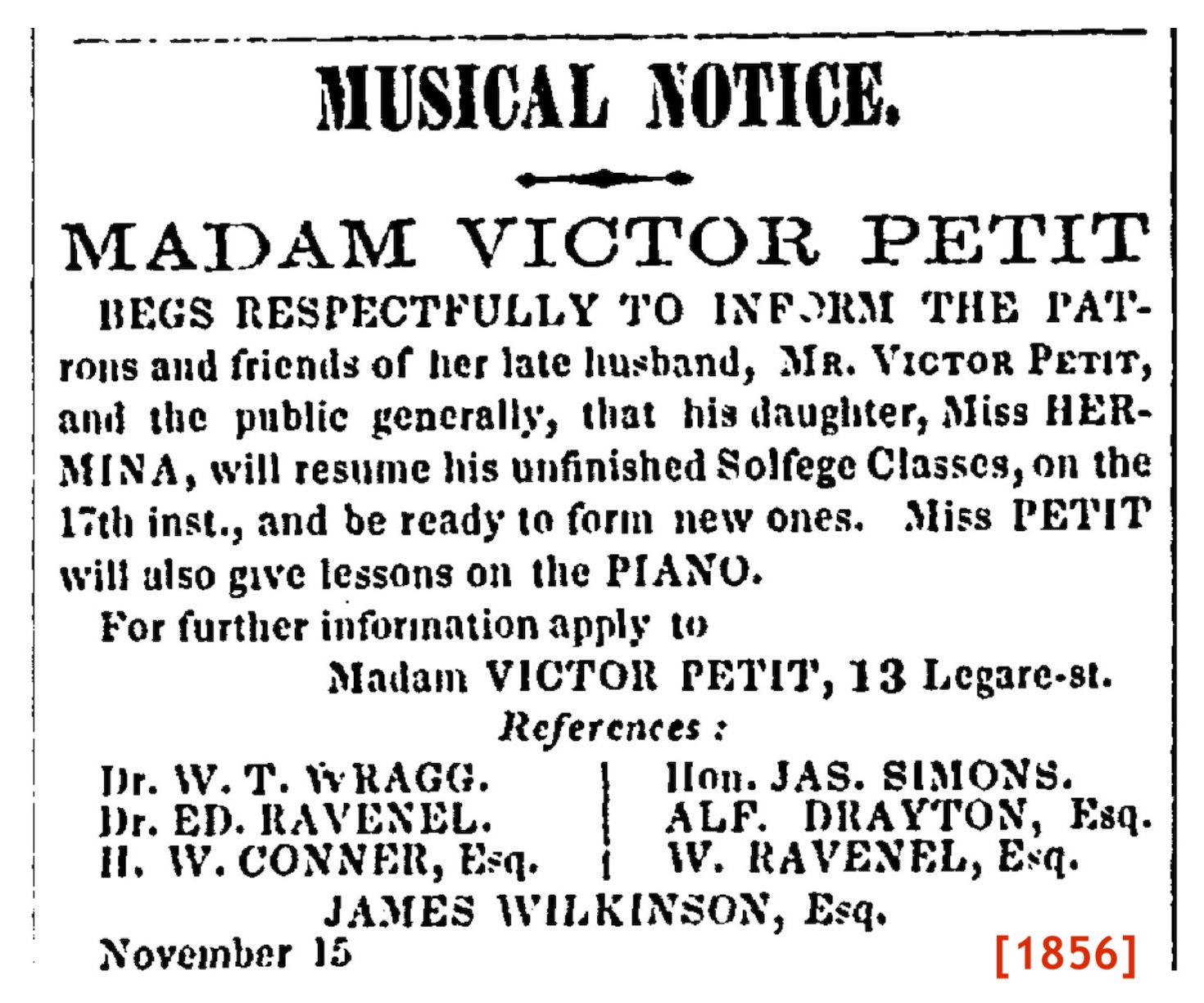

Blanche Hermine Petit was just a precocious young teenager in Charleston when her family dynamic experienced a dramatic change in 1856. During a yellow fever epidemic that autumn, her brother, Alfred, then her father, Victor, succumbed to the mosquito-borne illness.[13] Shortly thereafter, the widow Marie Petit announced via the local newspaper that her daughter, “Miss Hermina,” will resume the “unfinished solfege classes” of the late Victor Petit at their new residence in Legare Street. In addition, thirteen-year-old Blanche was ready to form new solfège classes and offer lessons on the piano to individuals and classes.[14] Her childhood, already more regimented and stressful than that of most of her female peers, was effectively finished. From that point onward, Blanche became a working musician whose labors sustained her remaining family. All thoughts of a performing career outside of Charleston evaporated as the teenager worked to keep a roof over her head.

Blanche Petit used her immense musical talents to thrive in Charleston during the late 1850s, and her local reputation received a significant boost by the visit of an international musical celebrity. The Swiss-born piano virtuoso Sigismond Thalberg, who embarked on a tour of North America in 1856, arrived in the Palmetto City in January 1858. His plan to present a pair of concerts at Institute Hall excited Charlestonians to such a degree that he extended his stay another week and presented a total of five sold-out performances. At his farewell event, held at Hibernian Hall on February 2nd, Thalberg invited fifteen-year-old Blanche Hermine Petit to join him on the stage for a piano duet. The forty-five year old keyboard legend played the role of accompanist at a small grand piano, while young Blanche took center stage at a larger concert grand. Together they rendered an intoxicating performance of Thalberg’s virtuosic fantasia on a theme from Vincenzo Bellini’s famous opera, Norma. That concert represented a pinnacle of Charleston’s antebellum musical life, and it cemented Blanche Petit’s reputation in her adopted home.[15]

The secession of South Carolina from the United States in December 1860 and the commencement of civil war in Charleston in April 1861 significantly curtailed the city’s cultural life for many years to come. The war overshadowed Blanche’s rise to adulthood, but did not destroy her ability to thrive. In April 1863, the twenty-year-old pianist married a widower more than twice her age, Pierre “Peter” Julius Barbot (1819–1887). A Charleston-born merchant of French ancestry, P. J. brought two surviving children from his previous marriage and welcomed six more during the ensuing two decades with Blanche. Throughout all of these years, however, Blanche Barbot, as she became known, sustained an active career as a professional performer and teacher of music in the Palmetto City.[16]

In October 1865, six months after the collapse of Confederate Charleston, Mrs. P. J. Barbot resumed her courses of instruction in vocal and instrumental music at her residence at the southwest corner of Smith and Montagu Streets. She also taught piano, singing, and drawing at her mother’s boarding and day school in Broad Street.[17] Blanche became organist for St. Mary’s Catholic Church on Hasell Street, training volunteer singers and organizing regular musical performances, and later moved to the organ bench of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church.

Throughout the late 1860s and early 1870s, Blanche also organized, rehearsed, and conducted numerous public concerts staged both for entertainment and to raise money for charitable causes. All of this activity elicited significant praise from the local community and added to the young mother’s growing musical reputation. As the Charleston Courier noted in the spring of 1869, prior to a performance of Rossini’s Stabat Mater at St. Mary’s Church, “Mrs. Barbot’s name itself, is a sufficient guarantee, in this community, that the music will be of the highest order. We advise all lovers of refined music to provide themselves with cards of admission at once.”

The highlight of local musical activity during the early 1870s was a performance of Haydn’s oratorio, The Creation, with a chorus of fifty voices accompanied by Madame Barbot on the piano. Their performance on March 12th, 1873 at Freunschaftsbund Hall (southwest corner of Meeting and George Streets) was so successful that the entire production was repeated a week later at the larger Hibernian Hall. Predicting an artistic triumph even before the curtain rose, the Charleston Daily News directed attention to the thirty-year-old conductor: “Mrs. P. J. Barbot has had the direction and management of the undertaking from the beginning, and too much cannot be said in praise of her energy in promoting the love and practice of classical music. It is hoped that the coming performance will lead to the formation of a musical society, which will render in time the masterpieces of Handel, Mendelssohn and Haydn.”[18]

The city’s most significant post-Civil War musical organization, the Charleston Musical Association, was organized by a group of affluent White men in the spring of 1875. Having witnessed the renaissance of cultural life in the war-shattered city, the founders of the Association drafted the community’s preeminent talent, Blanche Barbot, to direct its musical efforts. For the next twenty-eight years, the former child prodigy and mother of six served as the artistic director and conductor of Charleston’s most prestigious concerts of vocal and instrumental music. Blanche was a legend in her own time, whose performances at the keyboard and command of large musical forces never failed to impress local audiences. Extoling the success of the concert organization in 1876, the News and Courier summarized community sentiment in the following words: “The first honor must be awarded to the musical director, Madame Barbot, to whose musical culture, executive ability and unwearying [sic] labor the success of the [Charleston Musical] Association is mainly due. To this accomplished lady and to the ladies and gentlemen of the Association the city owes a debt of hearty thanks.”[19]

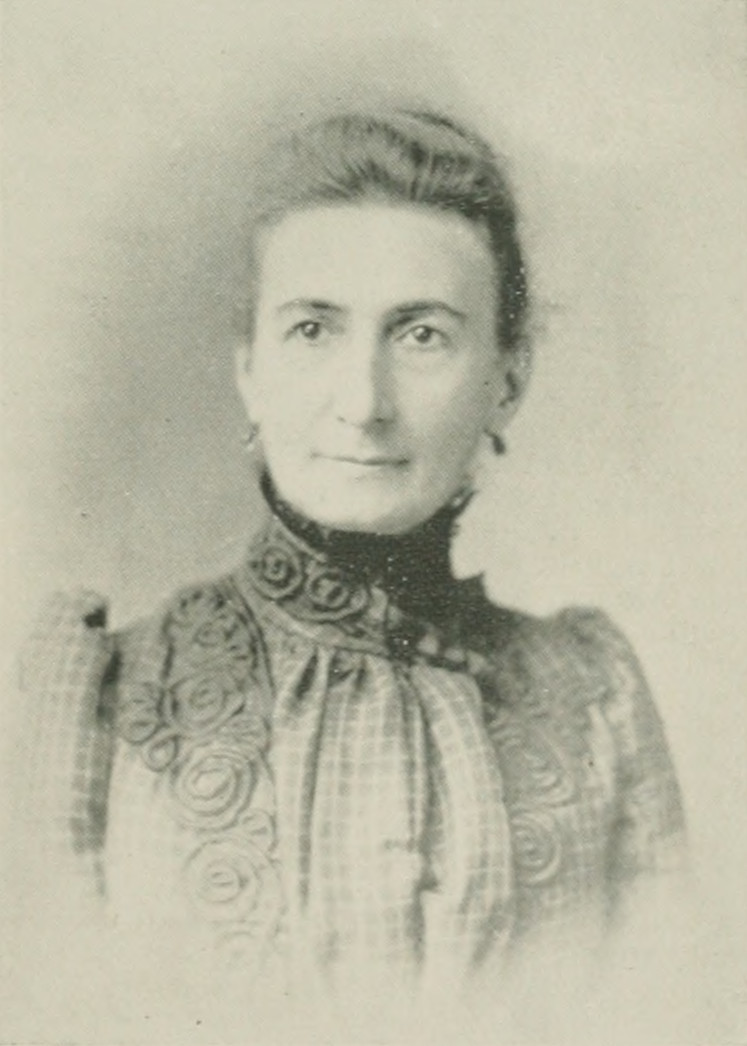

Although successive pregnancies occasionally required brief pauses in her career, Blanche Barbot never disappeared from public view for more than a few weeks at a time during the second half of the nineteenth century. In the spring of 1882, for example, one month after the birth of youngest daughter, Blanche, Madame Barbot became organist and music director for Charleston’s Catholic Pro-Cathedral—a position she held for the rest of her life. Long after the death of her husband in 1887, she taught music to her own children and to those of others in the community, exhibiting a passion for artistic work that few women or men could sustain. An 1893 publication profiling “leading American women from all walks of life” included a dense summary of Madame Barbot’s achievements and the only-known photograph of the fifty-year old pianist.[20]

The Charleston Musical Association continued its annual series of vocal and instrumental concerts into the twentieth century, but its institutional vigor faded into obscurity after the spring of 1903. The organization’s sixty-year old director continued to appear in local concerts in subsequent years, however, and on the organ bench of the new Catholic Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, consecrated in 1907. Madame Barbot’s efforts to sustain the musical arts in Charleston succeeded in attracting new talent to the city—other musicians who took an increasing share of the burden of teaching, performing, and organizing concerts in the community. While the phonograph, moving pictures, airplanes, and automobiles distracted the youth of the early 1900s, and the Great War in Europe dampened interest in older cultural traditions, Blanche Barbot quietly retired to a smaller domestic sphere of well-deserved rest.

In the spring of 1919, a long-time admirer named J. Gilmore Smith organized a retrospective of Madame Barbot’s illustrious career that spanned seven decades. The purpose of this review, said Smith in a lengthy essay published by the Charleston News and Courier, was to ensure that his favorite musical icon received the community’s thanks for her significant artistic contributions before her departure from the mortal realm.[21] His efforts were well timed, as the once-agile pianist was then in physical decline.

Blanche Hermine Petit Barbot died at her long-time residence, No. 51 Smith Street, on 17 December 1919, just a few days short of her 77th birthday.[22] Her marble headstone at St. Lawrence Cemetery does not recount the long narrative of her colorful life, but ample evidence of her cultural contributions survive in scrapbooks and archives of past generations. From a precocious European childhood filled with artistic promise, Mlle. Petit crossed the Atlantic to experience loss and hardship in the provincial city of Charleston. By channeling her creative energies into an impressive musical career, she sustained her family and invigorated the cultural life of her adopted home. While raising a large family, Blanche Barbot cultivated a sterling professional reputation during an era when most American women struggled for equal rights and recognition. “It is natural now to think of her,” wrote an admirer after her death in 1919, “as simply continuing in heaven to sound the glorious strains which here on earth comforted and uplifted so many through the years she was with us.”[23]

[1] Articles published in the Charleston News and Courier on 20 April 1919 and 18 December 1919 both state she was born in Brussels on 27 December 1842. According to a typescript of family births, marriages, and deaths, found among the Barbot family papers at the South Carolina Historical Society (hereafter SCHS; collection #1005), and according to an 1893 publication citied below, Blanche Hermine Petit was born on 28 December 1842.

[2] Charleston Courier, 13 April 1853, page 2, “Mrs. Victor Petit.”

[3] See the newspaper clippings in Blanche Petit Barbot’s personal scrapbook in the Barbot Family Papers (collection #1005) at the South Carolina Historical Society, box and folder 11/68/4.

[4] See clippings in the aforementioned scrapbook and New York Times, 16 June 1852, page 1, “Child’s Concert.”

[5] Phase de New York, 29 May 1852, found in the scrapbook within the Barbot Family Papers at SCHS.

[6] Courier, 17 November 1852, page 1.

[7] Courier, 19 November 1852, page 1; Courier, 22 November 1852, page 2.

[8] Courier, 4 January 1853, page 2; Courier, 13 January 1853, page 2.

[9] Courier, 4 January 1853, page 5, “Philharmonic Society of Charleston”; Courier, 15 January 1853, page 2, “The Philharmonic Society of Charleston”; Courier, 20 May 1853, page 2, “Charleston Philharmonic Society.”

[10] Courier, 13 April 1853, page 2, “Mrs. Victor Petit.”

[11] Courier, 6 October 1853, page 2, “Musical Instruction”; and editorial, “As will be perceived from a notice in another column. . . .”

[12] Courier, 8 November 1853, page 2, “Victor Petit’s First Artistic Concerts!”; Courier, 15 November 1853, page 2; Courier, 23 November 1853, page 2; Courier, 24 November 1853 (Thursday), page 2.

[13] Courier, 5 September 1856, page 3; Mercury, 27 October 1856, page 2; Courier, 5 November 1856, page 2, “Death of an Eminent Musician.” The latter notice described Victor as “a native of Quievrain, in Belgium, [who] died on Sullivan’s Island, near Charleston, South Carolina, on the 26th of October, 1856, after a short illness.”

[14] Courier, 15 November 1856, page 2, “Musical Notice.”

[15] Thalberg’s visit to Charleston was discussed in numerous newspaper articles throughout January 1858; see especially Courier, 27 January 1858, page 2, “Thalberg and Vieuxtemps”; Courier, 3 February 1858, page 2, “The Farewell concert of Mr. Thalberg.”

[16] According to a typescript of family births, marriages, and deaths in the Barbot family papers at SCHS, Blanche Hermine Petit married Pierre Julius Barbot on 8 April 1863. They had six children: Charles Julius (1864), Hermine Aimée (1866), Antoinette (1868), Ione (1870), Philip Reginald (1874), and Blanche Hermine (1882).

[17] Courier, 5 September 1865, page 2, “Vocal and Instrumental Music”; Courier, 3 October 1865, “Mrs. P. J. Barbot”; Courier, 6 December 1865, page 4, “French and English Boarding and Day School for Young Ladies.”

[18] Charleston Daily News, 19 December 1872, page 4, “The Creation”; Daily News, 8 March 1873, page 2, “The Creation”; Daily News, 13 March 1873, page 4, “Haydn’s ‘Creation’”; Daily News, 17 March 1873, page 1, “Haydn’s Creation”; Daily News, 19 March 1873, page 2, “Oratorio,” and page 4, “The Second Performance of the Oratorio of the Creation”; Daily News, 21 March 1873, page 4, “The Oratorio of the Creation.”

[19] News and Courier, 24 May 1876, page 4, “The Musical Association.”

[20] Frances Elizabeth Willard and Mary Ashton Rice Livermore, eds., A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-Seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life (New York: Charles Wells Moulton, 1893), page 53.

[21] Charleston News and Courier, 20 April 1919, section III: 3, 5, “Looking Backward Through A Vista of Fifty Golden Musical Years: An Appreciation and A Reminiscence of Mme. Blanche Hermine Barbot. The Interesting Career of an Artist Charleston Has Long Delighted to Honor,” by J. Gilmore Smith. Note that the author derived most of the early details included in this article from Madame Barbot’s scrapbook that is now part of the Barbot Family Papers at SCHS.

[22] News and Courier, 18 December 1919, page 12, “Obituaries” and “Mme. B. H. Barbot Has Passed Away.”

[23] News and Courier, 18 December 1919, page 4 (editorial), “Madame Barbot.”

NEXT: Charleston’s First Market and Place of Public Humiliation

PREVIOUSLY: Florence O'Sullivan: South Carolina's Irish Enigma

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments